Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F004BX106CA

Redwood/Douglas-fir/California huckleberry/western swordfern, hills, soft sandstone, very gravelly loam

Accessed: 03/13/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

Classification relationships

There is no relationship to other established classifications.

Associated sites

| F004BX107CA |

Redwood/western swordfern, hills, soft sandstone, clay loam F004BX107CA occurs in conjunction with F004BX106CA in the same geographic area. |

|---|---|

| F004BX111CA |

Redwood/western swordfern-redwood sorrel, floodplains and terraces, loam F004BX111CA is found in conjunction with F004BX106CA in the same geographic area. |

Similar sites

| F004BX107CA |

Redwood/western swordfern, hills, soft sandstone, clay loam F004BX107CA may resemble or be confused with F004BX106CA because the two sites are found in association with each other and the vegetation may initially appear similar. In F004BX106CA the shrub layer of California huckleberry dominates the understory, and in F004BX107CA, the forb layer of western swordfern dominates the understory. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Sequoia sempervirens |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Vaccinium ovatum |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Polystichum munitum |

Physiographic features

This ecological site is found primarily along the coast and inland between Goldbluffs beach and Prairie Creek, with some areas northeast of Orick and east of Prairie Creek. It occurs on slightly convex summits and shoulders of narrow ridges and backslopes of hills. These hills are strongly sloping to steep.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hill

(2) Ridge |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 6 – 309 m |

| Slope | 9 – 50% |

| Water table depth | 152 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate is humid with cool, foggy summers and cool, moist winters. Coastal influence limits the diurnal range in temperatures. Average summertime temperatures range from 65 to 70 degrees F. The mean annual precipitation ranges from 60 to 80 inches.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 325 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 325 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 2,032 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Influencing water features

There are no influencing water features on this site.

Soil features

These well-drained, very deep soils developed from colluvium and residuum derived from weakly consolidated sandstone and a conglomerate of the Prairie Creek Formation. They are very strongly to strongly acidic at 40 inches with a dominantly loamy subsurface rock content ranging from very gravelly to extremely gravelly.

MU Component

293 Goldbluffs

294 Goldbluffs

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Very gravelly loam |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate to moderately rapid |

| Soil depth | 152 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 25% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0 – 5% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

2.54 – 10.16 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

0% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

4.5 – 5.5 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

40 – 80% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0% |

Ecological dynamics

The historical origins of fires within the northern Redwood Region remain unknown. Lightning-ignited fires are considered rare. However, Native American burning is thought to have played a major role by burning fires from the interior into the redwood zone (Veirs, 1996). Natural fire intervals ranged from 500 to 600 years on the coast, 150 to 200 years on intermediate sites, and 50 years on inland sites. The northern range of redwoods evolved within a low to moderate natural disturbance regime. (Veirs, 1979).

Surface fires likely modified the tree species composition by favoring the thicker-barked redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and killing western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus) and grand fir (Abies grandis) (Veirs, 1979). Western hemlock's shallow roots and thin bark make it susceptible to fire damage (Arno, 2002). The establishment of a western hemlock understory is increased by surface fires. This is due to the exposure of mineral-rich soil and the reduction of other plant competition (Veirs, 1979, Williamson, 1976). Tanoak seedlings and sapling-sized stems are often top-killed by surface fire, though larger stems may survive with only basal wounding (Tappeiner, 1984).

Both redwood and tanoak have the ability to re-sprout following fire (Veirs, 1996). After fire, redwood may sprout from the root crown or from dormant buds located under the bark of the bole and branches (Noss, 2000). The sprouting ability of redwood is most vigorous in younger stands and decreases with age. Frequent fire reduces tanoak’s sprouting ability and tends to keep understories open (Arno, 2002). Fire exclusion would allow for the gradual increase of tanoak in the understory (McMurray, 1989).

A moderate fire could lead towards more of a mosaic in regeneration patterns. Patches of trees would be killed leaving others slightly damaged or unharmed. Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) regeneration would be favored in the large gaps that are created following a moderate fire, potentially leading to a larger proportion of Douglas-fir to redwood for several centuries (Agee, 1993). Without these gaps caused by fire, Douglas-fir regeneration is unsuccessful, and with continued lack of disturbance it may slowly be replaced by redwood as the dominant canopy species (Veirs, 1979, 1996).

California huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum) is normally a fire-dependent shrub species; little is known concerning it's adaptation to fire under low to moderate fire return intervals (Tirmenstein, 1990). It is a common species in both moist and dry redwood environments. Sprouting is widespread following fire and recovery may be rapid.

Other potential disturbances in the redwood zone include winter storms that can cause top breakage. This breakage may kill individual or groups of trees and create small openings from windfall (Noss, 2000). This would likely favor the establishment of redwood and other shade tolerant conifers. On alluvial sites with periodic flooding, redwood may dominate, along with other colonizing hardwoods (Veirs, 1996). Where existing redwoods are inundated, new roots develop in newly deposited silt (Veirs, 1996).

Past harvesting and the use of fire as a slash treatment has altered species composition on many sites (Noss, 2000). Within many areas of the park, aerial seeding of Douglas-fir has led to a 10:1 ratio of Douglas-fir to redwood (Noss, 2000).

Redwood's interior range is largely contained within the coastal fog belt. Coastal fog ameliorates the effects of solar radiation on conifer transpiration rates (Daniel, 1942). Research in the redwood region (Dawson 1998) has indicated that fog drip and direct fog uptake by foliage may contribute significant amounts of moisture to the forest floor during summer months and over the course of the year.

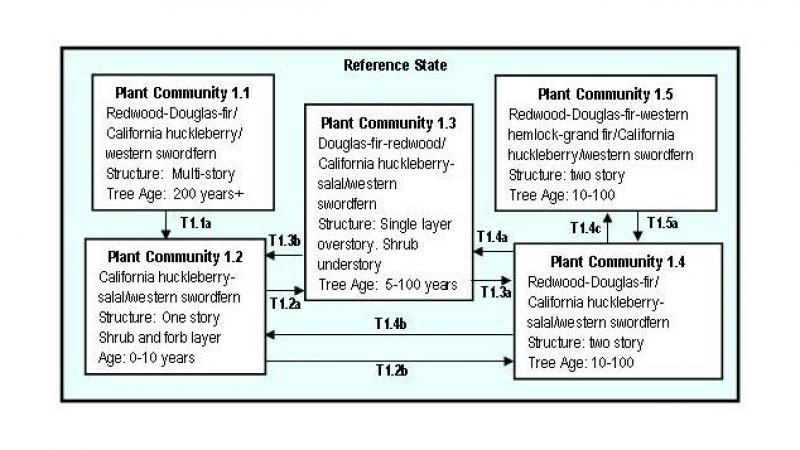

State and transition model

Figure 4. Redwood-Douglas-fir/California huckleberry/swordfe

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State - Plant Community 1.1

Community 1.1

Reference State - Plant Community 1.1

The characteristic plant community for this site is the reference plant community. Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) dominates the overstory with Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) making up a small percentage of the total conifer canopy cover. The incidence of Douglas-fir increases near upper slopes and summits. Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) is also occasionally present and may replace Douglas-fir near the coast. Tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus) is found in the sub-canopy, though usually in very low numbers. Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophyllia) and grand fir (Abies grandis) may also be found. The shrub layer is patchy, but consist predominantly of California huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum), with red huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium) and salal (Gaultheria shallon) occasionally present in lesser amounts. Ground cover is dominated by western swordfern (Polystichum munitum). T1.1a – Block harvesting and post-harvest burning may produce an initial plant community of California huckleberry and western swordfern. See PC#1.2.

Forest overstory. The main overstory is primarily redwood, with a lesser amount of Douglas-fir.

Average Percent Canopy Cover:

Main canopy

Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)

70-95%

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) 5-20%

Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophyllia) <5%

Grand fir (Abies grandis) <5%

Tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus) 5-10%

Forest understory. The patchy shrub understory is dominated by California huckleberry. Other shrubs include red huckleberry and salal. Western swordfern and redwood-sorrel (Oxalis oregano) are the dominant forbs in the understory.

Average Percent Canopy Cover

California huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum) 20-40%

Red huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium) 5%

Salal (Gaultheria shallon) <5%

Western swordfern (Polystichum munitum) 20-35%

Redwood-sorrel (Oxalis oregano)

0-5%

Table 5. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 70-100% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 25-45% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 0% |

| Forb foliar cover | 10-25% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 25-85% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-5% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 0% |

Table 6. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | – | – | 0-5% | – |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | – | – | – | 5-30% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | – | – | – | – |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | – | 30-40% | – | – |

| >1.4 <= 4 | – | 0-15% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | 0-5% | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | 0-5% | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | 0-10% | – | – | – |

| >37 | 70-100% | – | – | – |

State 2

Plant Community 1.2

Community 2.1

Plant Community 1.2

Sprouting of evergreen shrubs is stimulated by cutting and burning (Adams, et al 1992, Termenstien 1990). The shrub community that develops immediately following harvesting may be dominated by California huckleberry and salal. Western swordfern may also be common in the forb layer. If a seed source is present, Douglas-fir would infill. Redwood would also re-sprout. T1.2a – The proportion of Douglas-fir to redwood could be increased if a good seed crop were present to allow for a substantial natural infill of Douglas-fir. With no significant additional disturbances, this plant community could be dominated by a Douglas-fir and redwood overstory, with California huckleberry, salal and western swordfern below. A similar plant community could be established through brush management and tree planting. See PC#1.3. T1.2b – Without management, redwoods would sprout and infill of Douglas-fir may take place. Redwood sprouts may dominate if there is a lack of a good Douglas-fir seed crop. With tree planting, in conjunction with either brush management or chemical control, shrub growth could be controlled. Conifers could be established by being released from brush competition. Redwood would likely be dominant over Douglas-fir. See PC#1.4.

State 3

Plant Community 1.3

Community 3.1

Plant Community 1.3

Douglas-fir infill and redwood sprouts would eventually form an overstory, with a California huckleberry and salal brush layer below. T1.3a – With continued growth, redwood eventually surpasses Douglas-fir in height and dominates the overstory. The shrub community of California huckleberry and salal would be maintained in the understory. With early stand management and thinning of Douglas-fir, redwood dominance and growth could be accelerated. See PC#1.4. T1.3b – Block harvesting and post-harvest burning would set the plant community back to shrubs. See PC#1.2.

State 4

Plant Community 1.4

Community 4.1

Plant Community 1.4

The plant community is characterized by redwood and Douglas-fir in the overstory, with California huckleberry and salal in the shrub layer. Western swordfern dominates the forb layer. T1.4a – Partial cutting of redwood could result in an increase in regeneration and infill of Douglas-fir, increasing the proportion of Douglas-fir to redwood. See PC#1.3. T1.4b – If block harvested and burned, the plant community would again be dominated by evergreen shrubs. Total shrub cover could increase. See PC#1.2. T1.4c – Fire exclusion from the site could lead to an increase in infill of western hemlock and possibly grand fir on the site. See PC#1.5.

State 5

Plant Community 1.5

Community 5.1

Plant Community 1.5

With fire exclusion, western hemlock and grand fir may infill to become more common, though they would still be minor components of the overstory. Redwood infill also continues to occur at a very low level. T1.5a – Fire, though rare, would kill young western hemlock and grand fir, and could create suitable conditions for Douglas-fir regeneration. See PC#1.4.

Additional community tables

Interpretations

Animal community

The Redwood forest provides habitat for many species of mammals and native birds. Predators include black bear, fisher and marten, mountain lion, fox and bobcat. Ungulates included deer and elk, which use the forested areas for foraging and cover.

Many bird species use the redwood forest on a seasonal basis. Bird species include warblers, tanagers, sparrows, blackbirds, the Marbeled Murrelet, the Northern spotted owl and the Bald Eagle.

Common reptiles found in forested areas would include the alligator lizard and garter snake.

Amphibians are mostly associated with riparian and wetland areas. The northwest salamander and two newt species spend much of their lives in upland habitat.

Hydrological functions

These soils have a slow to moderate infiltration rate when thoroughly wet.

The site is subject to erosion where adequate vegetative cover is not maintained. Road building, timber harvest, and site preparation for planting may increase surface erosion and potential for mass wasting.

Limitations to construction of trails and camp areas may exist due to slopes and the amount of rock fragment in the soil.

Hydrologic Group

Goldbluffs 293--B

Goldbluffs 294--B

Recreational uses

Hiking, bird watching, wildflower viewing.

Wood products

Redwood is a highly valued lumber because of its resistance to decay. Uses of redwood include house siding, paneling, trim and cabinetry, decks, hot tubs, fences, garden structures, and retaining walls. Other uses include fascia, molding and industrial storage and processing tanks.

Douglas-fir is employed in residential structures and light commercial timber-frame construction. It is also used for solid timber heavy duty construction such as pilings, wharfs, bridge components and warehouse construction.

Other products

Redwood burls are used for tabletops, veneers, bowls and other turned products. Redwood bark is widely used as garden mulch.

Douglas-fir is a very desirable Christmas tree; branches and cones are also used as materials for Christmas wreaths.

California huckleberries are made into wine, as well as processed into pie fillings for home and commercial use. Foliage of the California huckleberry is used by florists in floral arrangements and to make Christmas decorations.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Data was collected at soil pits. Transects were run along trails within Prairie Creek.

Soil Pit #

04-18

04-34

04-35

Other references

Agee, James K., 1993. Fire Ecology of Northwest Forests. P 187-225.

Arno, Stephen H. and Allison-Bunnel, Steven. 2002. Flames in Our Forest, Disaster or Renewal? Island Press.

Burns, Russel M. and Honkala, B.H., Ed., 1990. Silvics of North America, Volume 1, Conifers. Agricultural Handbook 654. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

Crane, M. F. 1990. Rhododendron macrophyllum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis [2005, November 9.]

Daniel, T. W. 1942. The comparative transpiration rates of several western conifers under controlled conditions. PhD. diss., University of California. Berkeley.

McMurray, Nancy E. 1989. Lithocarpus densiflorus. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2006, June 2].

Noss, Reed, F., editor. 2000. The Redwood Forest. 377 pages.

Silvics of North America. 1990. USDA Handbook 654

Tappeiner, John C., II; Harrington, Timothy B.; Walstad, John D. 1984. Predicting recovery of tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus) and Pacific madrone (Arbutus menziesii) after cutting or burning. Weed Science. 32: 413-417.

Tirmenstien, D. 1990. Vaccinium ovatum.

In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis

Viers, Stephen D. 1996. Ecology of the Coast Redwood. Conference on Coast Redwood Forest Ecology and Management. P 9-12.

Viers, Stephen D. 1979. The Role of Fire in Northern Coast Redwood Forest Dynamics. Conference on Scientific Research in the National Parks.

Williamson, Richard L.; Ruth, Robert H. 1976. Results of shelterwood cutting in western hemlock. Res. Pap. PNW-201. Portland, OR: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station. 25 p.

Contributors

Judy Welles

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.