Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F004BX121CA

Redwood-Sitka spruce/salal-California huckleberry/western swordfern, marine terraces, marine deposits, sandy loam and loam

Accessed: 02/28/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

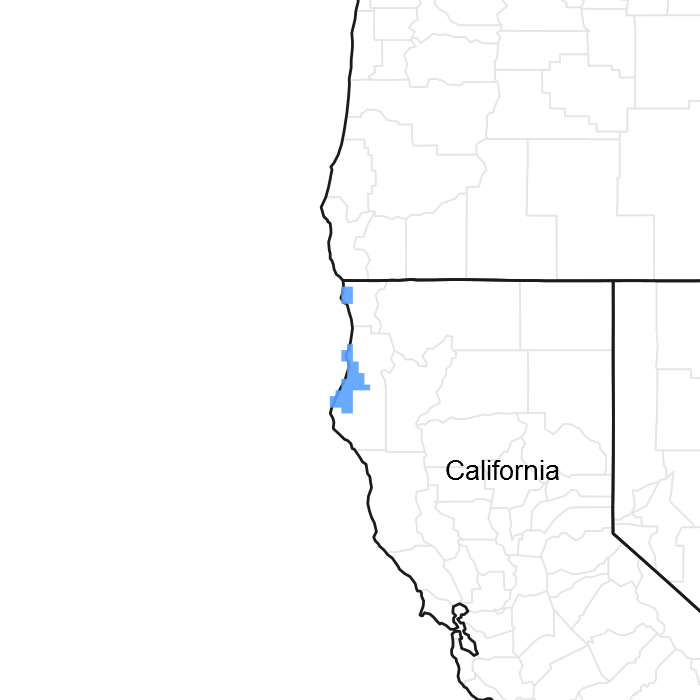

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

Associated sites

| F004BX118CA |

Sitka spruce-redwood/salal/western brackenfern, marine terraces, marine deposits, fine sandy loam F004BX118CA is often found adjacent to this ecological site but it has Sitka spruce as the dominant overstory species and is located on a younger marine terrace. |

|---|---|

| F004BX120CA |

Redwood-Sitka spruce/California huckleberry-salmonberry/western swordfern-deer fern, marine terraces, loam F004BX120CA can be found in conjunction with this ecological site. F004BX120CA has a similiar overstory but is less productive and overlies moderately well drained soils. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Sequoia sempervirens |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Gaultheria shallon |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Polystichum munitum |

Physiographic features

This ecological site is found on dissected marine terraces around Crescent City, CA and Trinidad, CA which were formed ~100,000 years ago. Although the concept for this ecological site is based on gentle slopes between 2-30%, areas of this site with slopes up to 60% can be found on the landscape. This site has a predominately northwest-facing aspect, towards the coast.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Marine terrace

|

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 250 – 515 ft |

| Slope | 2 – 30% |

| Aspect | NE, W, NW |

Climatic features

The climate of this ecological site is humid with cool, foggy summers and cool, rainy winters. Close proximity to the coast limits the diurnal and seasonal range in temperatures. Mean annual precipitation ranges from 60 to 80 inches and usually falls from October to May. Mean annual temperature is 52 to 57 degrees F.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 365 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 80 in |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Influencing water features

There are no influencing water features on this site.

Soil features

These very deep, well drained soils were formed in marine deposits on dissected marine terraces. These soils have a udic moisture regime and an isomesic temperature regime. Soil textures range from fine-loamy to coarse-loamy.

Soils that have been tentatively correlated to this ecological site include the following:

Soil Survey Area CA605 - Northern Humboldt and Del Norte

Mapunit Symbol Soil Component

185 Timmons

186 Timmons

257 Timmons

257 Arcata

258 Timmons

258 Arcata

258 Espa

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Loam (2) Fine sandy loam (3) Sandy loam |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Soil depth | 60 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

5% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

This ecological site occupies marine terraces outside Trinidad, CA and Crescent City, CA and is largely contained with the coastal fog belt. This site is of limited extent, and as no late successional stands of this site remain on the landscape the reference plant community is inferred.

Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and to a lesser extent Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) dominate this site which also has a productive understory of salal (Gaultheria shallon), California huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum), and western swordfern (Polystichum munitum). Although redwood is the dominant species on this site, the close proximity of to the coast may promote the establishment of Sitka spruce in the overstory (Franklin and Dyrness 1973).

The range of redwood is largely influenced by coastal fog, which ameliorates the effects of solar radiation on conifer transpiration rates (Daniel 1942). Fog is a critical source of water in the drier summer months for redwood, which has high transpiration rates. Fog drip and direct fog uptake by foliage may contribute significant moisture to understory species and the forest floor (Dawson 1998).

The northern range of redwoods evolved within a low to moderate natural disturbance regime, with severe fire intervals ranging from 500 to 600 years on the coast (Veirs 1979). Fires could have historically occurred by lightning ignition or deliberate setting by Native Americans to create desirable hunting habitat (Veirs 1996).

Surface fires may modify tree species composition by favoring thicker-barked redwood and killing grand fir (Abies grandis) and mature western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) (Veirs 1979). Redwood has the ability to resprout following fire from the root crown or from dormant buds under the bark of the bole and branches (Noss 2000), but shallow roots and thin bark make both western hemlock and Sitka spruce susceptible to fire damage (Arno 2002, Griffith 1992). However, frequent surface fire may promote establishment of western hemlock in the understory by exposing mineral-rich soil and reducing competition (Veirs 1979). In contrast, Douglas-fir seedling success may be decreased with a light fire regime (Mahony and Stuart 2000).

Moderate fire, wind disturbance, and management decisions can create a mosaic in regeneration patterns. Previous harvest and the use of fire as a slash treatment can alter species composition on many sites (Noss 2000) as repeated burning can favor resprouting of redwood and hardwoods and limit the regeneration of other conifers. Wind damage from winter storms can cause canopy top breakage which may kill individual trees or create windthrow gaps in the forest (Noss 2000). Canopy gap creation or selective redwood cutting could favor Sitka spruce growth and lead to a larger proportion of Sitka spruce in the stand.

Another mechanism through which Sitka spruce could become more firmly established in the stand is the propensity for Sitka spruce to rapidly invade adjacent coastal prairies after cessation of burning, grazing, or tilling (Franklin and Dyrness 1973). If land clearing and stump removal did occur, redwood regeneration may be slow to infill onto the site. Additionally, areas of this site on the boundary of coastal sea spray influence may have a greater composition of Sitka spruce as Sitka spruce has a high tolerance for salt spray (Zinke 1988). Some areas of this site adjacent to Lake Earl near Crescent City and Big Lagoon near Trinidad have a greater composition of Sitka spruce, suggesting the influence of both proximity to the coast and previous land clearing.

Slope may have a significant influence on the land use of this site. Some areas of this site around Crescent City with gentle (0-2%) slopes have been cleared and used for pasture. This pasture phase is not documented in the state and transition model for this site as it is of limited extent. Although of minimal acreage, this pasture land could be a distinct plant community phase if kept open by intensive grazing or clearing. As discussed in ecological site F004BX118CA, these pastures will be encroached by pioneer shrubs and conifer seedlings if grazing ceases. Additionally, sites with steeper slopes (reaching 60%) may have limitations on the type of harvesting methods that can be employed.

Red alder (Alnus rubra) is effective at rapidly colonizing disturbed landscapes following ground disturbance, harvest, or fire. Several thousand red alder per acre initially outgrow and dominate any conifers that become established in the disturbed area. Red alder is able to fix nitrogen with a symbiotic relationship with an actinomycete located on its root nodules (Bormann and Gordon 1984). These significant inputs of nitrogen to the ecosystem by red alder can increase overall stand productivity (Hart et al 1997). Shade intolerant red alder will eventually decrease in the stand as conifer regrowth reaches greater canopy heights.

California huckleberry and salal occupy a large percentage of the understory on this site. California huckleberry is a dominant shrub species across redwood ecological sites as it can thrive in both moist and dry environments. As California huckleberry is typically a fire-dependent species, sprouting can be widespread following natural fire or site preparation treatments (Tirmenstein 1990b). Salal increases significantly after harvest and can even reduce regeneration and stocking of Douglas-fir (Tirmenstein 1990a). Western swordfern can grow in a range of light conditions and can be often indicative of moist, productive forest habitat (Crane 1989).

This ecological site occupies young marine terraces near Trinidad and Crescent City. The marine terrace sequence around Trinidad demonstrates the fluctuations of sea level and tectonic uplift over the past 400,000 years. Six distinct marine terraces are identified in this area, the sediments of which we deposited during times of higher sea level (Woodward-Clyde Consultants). The youngest emergent terrace is found closest to the coast, and subsequently older terraces are found further east and at higher elevation. The oldest and highest terrace (Maple Stump) is found furthest east and exhibits the most soil development (Stephens 1982). Local eolian and colluvial deposits overlie the marine sediments on older terraces (Stephens 1982). The Savagecreek terrace, upon which this ecological site is found near Trinidad, is the second youngest of these six terraces and likely formed about 105,000 years. The marine terrace in the vicinity of Crescent City suggests similar deposition timing during sea level high stands (Lorenz and Kelsey 1999).

The effects of climate change on species distribution and viability need to be considered in this age of rapidly changed climate regimes. The western United States is already experiencing an increase in tree mortality across all tree cohort age classes, likely due to regional warming and water deficits (van Mantgem et al 2009). These forest structure changes may cause species to migrate to higher elevations, as much as 500-1000m, as temperatures increase in lower elevations (Urban et al 1993). Climate models project many different climate regimes for the north coast of California. One model predicts a warmer, wetter climate regime in which redwood may be able to expand into canyon live-oak-madrone and chaparral systems (Lenihan et al 2003). Climate change and its effects on vegetation patterns should be considered along with historical perspectives in ecological site development.

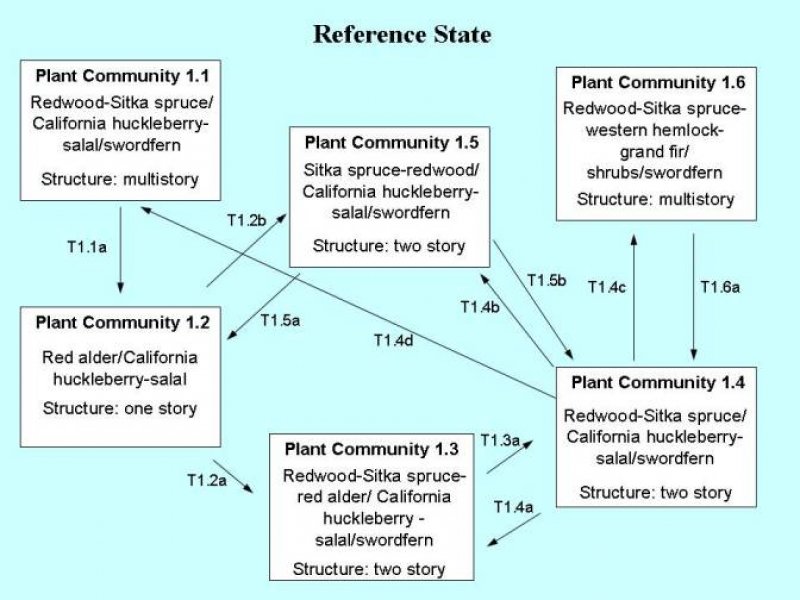

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 6 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State - Plant Community 1.1

Community 1.1

Reference State - Plant Community 1.1

The reference plant community for this ecological site consists of redwood and Sitka spruce in overstory and a mixed understory consisting of salal, California huckleberry, and swordfern. T1.1a) Block harvest or fire would open up light and nutrients for pioneer species and shrubs to dominate the site.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by redwood and Sitka spruce with intermixed Douglas-fir and grand fir.

Average Percent Canopy Cover:

redwood 20-80%

Sitka spruce 20-70%

Douglas-fir 0-20%

grand fir 0-5%

Forest understory. The understory of this ecological site is comprised of both shrubs and forbs with California huckleberry, salal, and swordfern contributing the greatest cover.

Average Percent Canopy Cover:

California huckleberry 15-35%

salal 5-20%

swordfern 10-30%

State 2

Plant Community 1.2

Community 2.1

Plant Community 1.2

This plant community phase occurs following a large scale disturbance such as block harvesting or severe fire. Pioneer species will stabilize soils and dominate the site for several years. T1.2a) Several years after a large disturbance, redwood will resprout and Sitka spruce will infill into the site. Red alder and shrubs will continue to be major species components of the site. T1.2b) A prolific nearby seed source could provide for Sitka spruce to quickly regenerate on the site, creating a Sitka spruce dominated canopy until redwood sprouts grow into the overstory.

State 3

Plant Community 1.3

Community 3.1

Plant Community 1.3

This plant community consists of redwood sprouts and Sitka spruce recruits gaining a place in the overstory intermixed with red alder. The understory remains dense but will begin to be shaded out. T1.3a) Mechanical or chemical hardwood management techniques may hasten the establishment and growth of conifers by decreasing competition for light from red alder and shrub species.

State 4

Plant Community 1.4

Community 4.1

Plant Community 1.4

Over time redwood and Sitka spruce will overtop and shade out red alder. T1.4a) Windthrow or other small scale disturbances could create a gap in the overstory for red alder and shrubs to colonize, providing for hardwood species along with conifers in the overstory. T1.4b) A selective redwood cut would leave Sitka spruce dominating the site as redwood sprouts grow in the subcanopy. T1.4c) Long term fire exclusion could result in western hemlock and grand fir infilling and becoming codominants in the overstory. 1.4d) Time and an intermediate disturbance regime could create the opportunity for the site to transition towards the reference plant community with a multi-layered canopy and more open understory.

State 5

Plant Community 1.5

Community 5.1

Plant Community 1.5

This plant community phase may arise if Sitka spruce infills rapidly or if a selective harvest of redwood occurs. Sitka spruce will continue to dominate the overstory for several decades if conditions for redwood sprouts are less than favorable. 1.5a) A block harvest would remove all overstory trees and open up light and nutrient resources for pioneer species to colonize the site. T1.5b) Several decades of redwood sprout regrowth would provide for a mixed overstory of redwood and Sitka spruce.

State 6

Plant Community 1.6

Community 6.1

Plant Community 1.6

This plant community phase could arise after long periods of fire exclusion. Western hemlock and grand fir, which can persist in the shady subcanopy, could become a dominant tree species on this site. T1.6a) A moderate to severe fire would open up the subcanopy and decrease the prevalence of western hemlock and grand fir.

Additional community tables

Interpretations

Animal community

California huckleberry leaves may be eaten by deer, and its berries are utilized by many bird and mammal species including bear, fox, squirrels and skunks.

Hydrological functions

The soils of this ecological site are very deep and moderately well drained or well drained. These soils have a moderately high rate of water transmission with low to high runoff.

Road building, timber harvest, and site preparation for planting may increase surface erosion and potential for mass wasting under current weather and soil conditions.

Hydrologic Group:

185--Timmons--C

186--Timmons--B

257--Timmons--

257--Arcata--

258--Timmons--

258--Timmons--

258--Espa--

Refer to the Soil Survey Manuscript for further information.

Recreational uses

This forested site would provide excellent hiking and pack trails.

Wood products

Redwood is a highly valued lumber because of its resistance to decay. Uses of redwood include house siding, paneling, trim and cabinetry, decks, hot tubs, fences, garden structures, and retaining walls. Other uses include fascia, molding and industrial storage and processing tanks.

Douglas-fir is employed in residential structures and light commercial timber-frame construction. It is also used for solid timber heavy duty construction such as pilings, wharfs, bridge components and warehouse construction.

Sitka spruce is used as saw timber, wood pulp and plywood. It has a high stength to weight ratio which is valuable for use as masts for sail boats, oars, boats and racing sculls. It is also valued for use in making guitars and for piano sounding boards.

Grand fir

Other products

California huckleberries are made into wine, and used by home and commercial processors for pie fillings. Berries from Rubus species can also be eaten raw or processed. Foliage of the California huckleberry and salal are used by florists in floral arrangements. Edible mushrooms can be found on this ecological site by experienced fungi identifiers.

Other information

Site productivity interpretations are based on the following site index curves:

Species Curve Base age

Redwood 930 100 years

Douglas-fir 790 100 years

Sitka spruce 490 100 years

Grand fir 35 50 years

Table 5. Representative site productivity

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Data was collected with forest plots at or near the location of soil pits. Plot numbers correspond to forest plots.

08F009 - Plot #9 in 2008

08F010

08F011

08F034

08F035

08F041

08F045

09F001

09F002

09F003

09F004

09F012

09F013

09F014

09F016

09F018

09F019

09F029

09F030

Type locality

| Location 1: Humboldt County, CA | |

|---|---|

| Township/Range/Section | T9N R1W S24 |

| UTM zone | N |

| UTM northing | 4555916 |

| UTM easting | 405965 |

| General legal description | USGS Rodgers Peak Quadrangle |

Other references

Agee J.K. 1993. Fire ecology of Pacific Northwest forests. Island Press. Covelo, CA.

Arno, S.F., Allison-Bunnell, S., 2002. Flames in our forest: disaster or renewal? Island Press, Washington, DC, 227 pp.

Bormann B.T. and Gordon J,C. 1984 Stand density effects in yound red alder planations:

productivity, photosynthate partitioning, and nitrogen fixation. Ecology 65: 394-402

Crane, M. F. 1989. Polystichum munitum. In: Fire Effects Information System. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Daniel, T. W. 1942.The comparative transpiration rates of several western conifers under controlled conditions. Ph. D. Thesis. U. of Calif., Berkeley. 190 p.

Dawson, T.E. 1998. Fog in the California redwood forest: ecosystem inputs and use by

plants. Oecologia 117: 476-485.

Franklin, Jerry F.; Dyrness, C. T. Natural vegetation of Oregon and Washington. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-8. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station; 1973.417 p.

Griffith, Randy Scott. 1992. Picea sitchensis. In: Fire Effects Information System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Hart, S.C., Binkley, D., and Perry, D.A. 1997. Influence of red alder on soil nitrogen transformations in two conifer forests of contrasting productivity. Soil Biol. Biochem. Vol. 29, No. 7, pp. 111 l-1123.

Lenihan, J.M., R. Drapek, D. Bachelet, R.P. Neilson. 2003. Climate change effects on vegetation distribution, carbon, and fire in California. Ecological Applications 13(6), 2003, pp. 1667–1681

Mahony T.M. and J.D. Stuart. 2000. Old-growth forest associations in the northern range of coast redwood. Madroño, Vol. 47 No. 1. pp 53-60.

Noss, R.F., editor. 2000. The redwood forest: history, ecology, and conservation of the coast redwoods. Save-the-Redwoods League. Island Press. Covelo, CA. 377 pages.

Polenz, M. and H.M. Kelsey, 1999. Development of a Late Quaternary Marine Terraced Landscape during On-Going tectonic Contraction, Crescent City Coastal Plain, California

Quaternary Research 52, 217–228.

Stephens, T.A., 1982, Marine terrace sequence near Trinidad, Humboldt County, California, Friends of the Pleistocene 1982 Pacific Cell Field Trip Guidebook, Aug. 5-8,

1982, p. 100- 105.

Tirmenstien, D. 1990a. Gaultheria shallon. In: Fire Effects Information System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis

Tirmenstien, D. 1990b. Vaccinium ovatum. In: Fire Effects Information System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis

Urban, D. L. M.E. Harmon C.B. Halpern. 1993. Potential response of Pacific Northwestern forests to climatic change, effects of stand age and initial composition Climate Change 23: 247-266.

van Mantgem, P.J., Stephenson, N.L., Byrne, J.C., Daniels, L.D., Franklin, J.F., Fulé, P.Z., Harmon, M.E., Larson, A.J., Smith, J.M., Taylor, A.H., and Veblen T.T., 2009. Widespread Increase of Tree Mortality Rates in the Western United States. Science 323:521-524.

Woodward-Clyde Consultants. 1982. Central and Northern California Coastal Marine Habitats: Oil Residence and Biological Sensitivity Indices: Final Report (POCS Technical Paper #83-5) Prepared for the US Minerals Management Service Pacific Outer Continental Shelf Region.

Veirs, S.D. 1996. Ecology of the coast redwood. Conference on coast redwood ecology and management. Pg 9-12.

Veirs, S.D. 1979. The role of fire in northern coast redwood forest dynamics. Conference on Scientific Research in the National Parks.

Contributors

Emily Sinkhorn

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.