Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R004BX102CA

Coastal scrub, hills, sandstone and mudstone, gravelly clay loam

Accessed: 12/22/2024

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

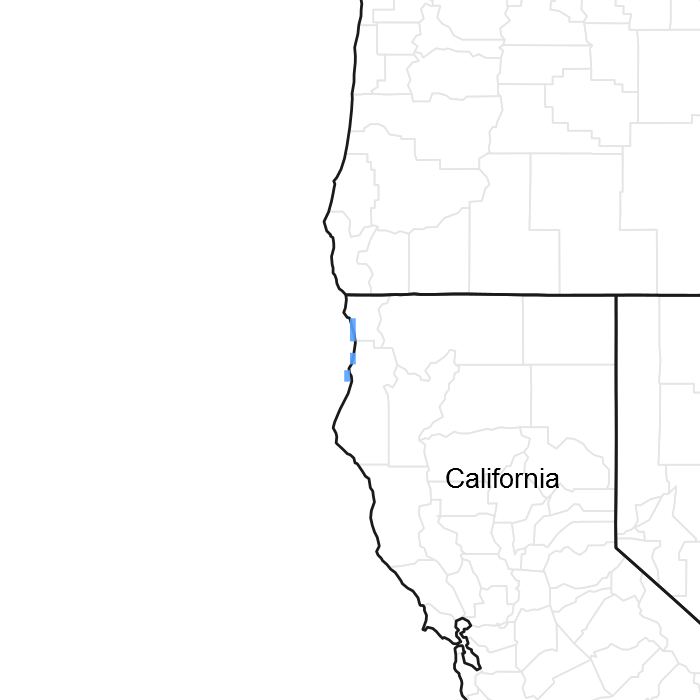

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

Associated sites

| F004BX110CA |

Sitka spruce-red alder/salmonberry/western swordfern, hills, sandstone and mudstone, clay loam Site F004BX110CA is often found in conjunction with this site. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Baccharis pilularis |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Heracleum lanatum |

Physiographic features

This ecological site is found along the coast throughout the survey area. It occurs on moist summits, shoulders, and back slopes of hills and debris slide areas, which vary from uniform to slightly convex. These areas exhibit inclines that are strongly sloping to steep.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hill

(2) Flow |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 0 – 213 m |

| Slope | 15 – 75% |

| Water table depth | 152 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate is humid, with cool, foggy summers and cool, moist winters. Coastal influence limits the diurnal range in temperatures. Summertime temperatures range from 60 to 70 degrees F. Mean annual precipitation ranges from 60 to 80 inches, and usually falls from October to May.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 332 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 332 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 1,778 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 4. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 5. Annual average temperature pattern

Influencing water features

There are no influencing hydrological features on this site.

Soil features

These well-drained, very deep soils developed from colluvium and residuum derived from mudstone and sandstone. They are neutral to moderately acidic at 40 inches with a dominantly loamy subsurface and rock content ranging from gravelly to extremely gravelly.

This ecological site has been tentatively correlated to the following soils: Redwood National and State Parks

MU Component

596 Flintrock

596 Highprairie

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Clay loam (2) Very gravelly clay loam |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow |

| Soil depth | 152 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 60% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0 – 5% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

5.08 – 17.78 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

0% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

5.6 – 6.5 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

15 – 60% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 10% |

Ecological dynamics

A complex mosaic of coastal prairie, scrub, and forest communities are found along the immediate coast, often with each plant community intergrading into the other*. Patterns of vegetation development within these communities are influenced by climate, topography, management history, and debris flow activity (Barbour and Major, 1977). The patchy nature of the coastal scrub and coastal prairies was undoubtedly created and perpetuated by the coastal Native American tribes (Keeley 2002). Many Native American tribes lived on the coastlines and manipulated the land to suit their needs for food and shelter. Periodic burning was one of the primary tools used to open up the prairies and limit the encroachment of scrublands and forests. Burning kept habitation areas open, enhanced wildlife habitats for hunting, and stimulated growth of numerous grasses and forbs that offered both subsistence and cultural significance (Sugihara and Reed, 1987).

By the 1800s, Europeans had settled into these areas and began domestic livestock grazing, primarily with sheep and cattle. At this time, active burning by Native Americans ceased. The coastal prairies were heavily grazed, likely reducing the reproductive capabilities and vigor of the native perennial grasses and forbs, which contributed to an overall decline in their population. Continuous grazing and the seed source introduction from plantings are believed to have caused a shift from native perennial grasses and forbs to one of non-native perennial and annual grasses and forbs.

Historically, the coastal prairies were thought to be dominated by native perennial grasses and forbs (Holland and Kiel, 1995). Northern coastal prairies are currently a mixture of both native and introduced perennial grasses including: fescues (Festuca spp.), sweet vernalgrass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata), Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), California oatgrass (Danthonia californica) and blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus).

Northern coastal prairies are subject to invasion of brush species such as coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis), Himalayan blackberry (Rubus discolor) and California blackberry (Rubus ursinus) (Heady, 1977). Coyotebrush is known to actively invade eroding areas (Steinburg, 2002) and may increase in grasslands if there is an absence of fire or grazing (Kirkpatrick and Hutchinson, 1980). Most species of blackberry reproduce both via seed and sprouting. Their growth is quite rapid, which allows the plants to spread vigorously throughout the area (Termenstien, 1989).

Scrub species are well adapted to the unstable, steep, and sometimes shallow soils and harsh coastal conditions commonly found at this site. Their longevity and reproductive success ensures their continued domination of the rocky, convex, and exposed cliff slopes of the coastline. Studies are lacking on the influences of soil and parent material on plant community composition and structure in the coastal scrub (Holland and Keil, 1995).

In some areas, natural disturbance of the coastal scrub community may allow the scrub to be perpetuated indefinitely (Barbour and Major, 1977). More severe, human-caused disturbances may lead to scrub invasion of coastal prairie. Some evidence suggests that the coastal scrub community is in a seral stage of progression from grassland to forest (de Becker, Holland and Keil, 1995). Within 50 years, transition to forest may occur in areas where soil and moisture conditions are suitable (Barbour and Major, 1977).

*Due to the level of soil mapping within Redwood National Park (Order III), coastal scrub and prairie are described together in this ecological site description. It is recognized that there likely are other discrete plant communities found within this general ecological site description.

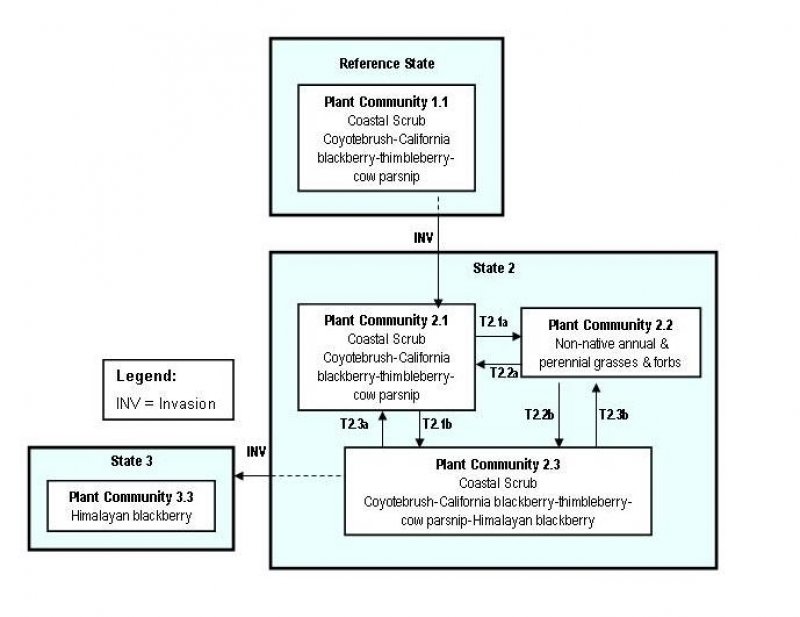

State and transition model

Figure 6. Coyotebrush coastal scrub model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 6 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Plant Community 5. Coyotebrush-California blackberry-himalayan blackberry-western swordfern

Community 1.1

Plant Community 5. Coyotebrush-California blackberry-himalayan blackberry-western swordfern

The plant community is dominated by a shrub layer that includes: coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis), California blackberry (Rubus ursinus), and Himalayan blackberry (Rubus discolor); as well as a dense understory layer of fern and forbs. Common ferns include western swordfern (Polystichum munitum) and western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum). Red alder (Alnus rubra) often occupies the small drainages within this plant community. Other shrubs found on this site may include cascara buckhorn(Frangula purshiana) and elderberry (Sambucus spp.). Other common plant species found on the site may include horsetail (Equisetum spp.), hedgenettle (Stachys spp.), vetch (Vicia spp.) and yarrow (Achillea ssp.). 5a) A combination of soil movement and disturbance in concave areas with moist conditions is thought to play an important role in the establishment of the thimbleberry-cowparsnip plant community, as freshly exposed soils in these areas are readily invaded by both species. Thimbleberry quickly creates dense thickets. Cowparsnip, a shade-tolerant forb, maintains itself under the canopy of the thimbleberry and reaches out over the top when flowering. 5b) Periodic fire could return the coyotebrush and blackberry communities back to native and introduced perennial grasses and forbs (refer to State 1). 5c) Sitka spruce may gradually infill when a seed source is present, and invasion may be facilitated by nurse logs (Franklin and Dyrness, 1973). More infill of sitka spruce may occur following a debris flow or human-caused disturbance, if a seed source is present. See PC#4.

State 2

Plant Community 1

Community 2.1

Plant Community 1

This plant community might have historically included: fescues (Festuca spp.), California brome (Bromus carinatus), blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus), bentgrass (Agrostis spp.), California oatgrass (Danthonia californica), tufted hairgrass (Deschampsia caespitosa), yarrow (Achilla spp.), aster (Aster spp.), daisy (Erigeron spp.), strawberry (Frageria spp.), cowparsnip (Heracleum lanatum), iris (Iris spp.), peas (Lathyrus spp.), vetch (Vicia spp.), flax (Linum spp.), lupine (Lupinus spp.), wild cucumber (Echinocystis lobata) and fireweed (Epilobium spp.). 1a) Historically, infill of sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) may have slowly occurred along the fringes of the prairies before expanding into the forest areas. Fallen trees may have acted as nurse logs for young sitka seedlings (Franklin and Dyrness, 1973). See PC#4. On some sites, sufficient infill of sitka spruce may progress to a point which is considered an irreversible threshold. At this time, accelerated practices would be needed to return to a grassland state. 1b) The past history of uncontrolled grazing, the seeding of introduced perennials, and the elimination of periodic burning all contributed to a reduction in native perennial species, as well as an increase in introduced perennial and annual grasses. See PC#2. 1c) In some areas, uncontrolled grazing of domestic livestock may have led to a plant community more heavily dominated by both annual grasses and forbs and introduced perennials. See PC#3. 1d) Commonly, with the eventual exclusion of fire and grazing, the plant community was readily invaded by coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis), California blackberry (Rubus ursinus), and Himalayan blackberry (Rubus discolor). The understory may have been dominated by western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinium) and western swordfern (Polystichum munitum). Areas of mass movement or human-caused disturbance may also be readily invaded by coyotebrush or blackberry. See PC# 5. Invasion by thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) and cowparsnip (Heracleum lanatum) may happen on side-slopes where there is a finer-textured sediment deposition, moist soil conditions, or where mass movement has occurred. Thimbleberry can quickly establish itself by seed as well as by vegetative sprouting (Tirmenstein 1989). Cowparsnip regenerates via seed and is suspected of regenerating through sprouting, though this is not well documented. See PC#6. 1e) The historic plant community was perpetuated through periodic burning by Native Americans.

State 3

Plant Community 6. Thimbleberry-cowparsnip

Community 3.1

Plant Community 6. Thimbleberry-cowparsnip

This plant community is dominated by thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) and cowparsnip (Heracleum lanatum). Cowparsnip is found in moist to semi-wet conditions. It reproduces by seed, but is believed to also reproduce vegetatively (Esser, 1995). Thimbleberry can grow on a variety of soil types and is common following a disturbance (Terminstein, 1989). This plant community may be stable for long periods of time. 6a) There may be potential for coyotebrush and blackberry to partially invade the thimbleberry-cowparsnip plant community in some areas. See PC#5. 6b) Sitka spruce may gradually infill when a seed source is present, and invasion may be facilitated by nurse logs (Franklin and Dyrness, 1973). See PC#4.

State 4

Plant Community 2

Community 4.1

Plant Community 2

The interpretive plant community may consist of both introduced and native perennial grasses and forbs, with widely varying ratios of native to non-native species. Introduced perennials and annuals may include annual vernalgrass (Anthoxanthum aristatum), orchardgrass (Dactylis glomeratum) and common velvetgrass (Holcus lanatus). Native perennials may include blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus), Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), and California oatgrass (Danthonia californica). Western brackenfern is also common on many sites. 2a) Infill of sitka spruce may slowly occur along the fringes of prairies, expanding into the forest area. Fallen trees may act as nurse logs for young sitka seedlings (Franklin and Dyrness, 1973). See PC# 4. 2b) Fire exclusion and reduction of grazing, may allow the plant community to be gradually invaded by coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis), California blackberry (Rubus ursinus), and Himalayan blackberry (Rubus discolor). The understory may be dominated by western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinium) and western swordfern (Polystichum munitum). These species also readily invade areas with mass movement or human-caused disturbance. See State 3, PC# 5. The transition to shrubs may reach a point at which it is considered an irreversible threshold. At this time, accelerated practices would be needed to return to State 1. 2c) Invasion by thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) and cowparsnip (Heracleum lanatum) may happen on side-slopes where there is a finer-textured sediment deposition, moist soil conditions, or where mass movement has occurred. Thimbleberry can quickly establish itself by seed as well as by vegetative sprouting (Tirmenstein 1989). Cowparsnip regenerates via seed and is suspected of regenerating through sprouting, though this is not well documented. See PC#6. The transition may reach a point at which it is considered irreversible and accelerating practices would be necessary to restore ecological processes and return to State 1. 2d) Periodic burning has maintained this plant community on some sites. 2e) Uncontrolled grazing in conjunction with the exclusion of fire could lead to a plant community dominated by annual grasses. forbs and introduced perennials. See PC#3.

State 5

Plant Community 3

Community 5.1

Plant Community 3

Annual grasses, forbs, and introduced perennials may come to dominate an area that has been subject to uncontrolled grazing. 3a) The plant community may return to grasslands dominated by perennial grasses if there is a reduction in grazing, an establishment of a prescribed grazing program or the use of prescribed fire. See PC#2.

State 6

Plant Community 4

Community 6.1

Plant Community 4

Sitka spruce may gradually infill when a seed source is present. Gradual invasion of sitka spruce may occur via nurse logs. (Franklin and Dyrness, 1973). Some areas such as debris flows may infill with sitka spruce more readily than others if a seed source is present. 4a) The use of prescribed fire or tree girdling may temporarily suspend infill of sitka spruce into prairie areas. 4b) The use of prescribed fire or tree girdling may temporarily suspend infill of sitka spruce into the coastal scrub.

Additional community tables

Interpretations

Animal community

Perennial grasslands provide a habitat for many species of birds and animals. A variety of snakes may be found, including the common garter snake and the western terrestrial garter snake. Moles, gophers, mice and voles all find habitat in the coastal grasslands. Birds that utilize the prairies for foraging include: owl, sparrow, turkey vulture, and red-tailed hawk. Mammals foraging throughout the prairies include bat, skunk, coyote, rabbit, Roosevelt elk and black-tailed deer.

Little is known concerning the use of coastal scrub by wildlife (de Becker, 1988). Due to the intricate mosaic of the two plant communities, it is thought that many of the same species that utilize coastal prairies may also be found in coastal scrub.

Hydrological functions

These soils have a moderately slow infiltration rate when thoroughly wet. They are very deep, well-drained and have a moderately fine texture. These soils have a moderate rate of water transmission.

Hydrologic Group:

Flintrock--D

Highprairie--C

Recreational uses

Recreational uses may be limited by steep slopes, the amount of rock fragment, and soil permeability rates.

Wood products

There are no wood products associated with this ecological site.

Other products

Traditional plants utilized for basket weaving are occasionally gathered from these areas.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

The ecological site is associated with the following sites:

Range data #06-07-RP, High Prairie

Other references

Barbour , Michael G., and Major, Jack, 1977. Terrestrial Vegetation of California. John Wiley and Sons.

Esser, Lora L. 1995. Heracleum lanatum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2006, November 14].

Franklin, Jerry F., and Dyrness, C.T., 1973. Natural Vegetation of Oregon and Washington. Oregon State University Press. 452 pp.

Heady, H.F., et al, 1977. Coastal Prairie and northern scrub. Pages 733-760 in Terrestrial Vegetation of California. California Native Plant Society Special Publication Number 9, Sacramento, CA.

Holland, V.L., and Keil, David J., 1995. California Vegetation. Kendall Hunt Publishing Company. 516 pp.

Keeley, Jon E. 2002. Native American impacts on fire regimes of the California coastal ranges. Journal of Biogeography. 29(3): 303-320.

Kirkpatrick, J. B.; Hutchinson, C. F. 1980. The environmental relationships of Californian coastal sage scrub and some of its component communities and species. Journal of Biogeography. 7: 23-38. [5608]

Mayer Kenneth E., Laudenslayer, William F., eds. A Guide to Wildlife Habitats of California. California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection., 1988.

Steinberg, Peter D. 2002. Baccharis pilularis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2006, November 16].

Sugihara, Neil G. and Reed, Lois J. 1987. Vegetation Ecology of the Bald Hills Oak Woodlands of Redwood National Park. Redwood National Park Research and Development. Technical Report 21.

Tirmenstein, D. 1989. Rubus parviflorus. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2006, August 17].

Tirmenstein, D. 1989. Rubus discolor. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2006, November 20].

Contributors

Judy Welles

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.