Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R004BX104CA

Middle prairie, mountain slopes, sandstone and mudstone, gravelly clay loam

Accessed: 02/08/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

Similar sites

| R004BX101CA |

Upper prairie, mountain slopes, sandstone and mudstone, clay loam |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Arrhenatherum elatius |

Physiographic features

This ecological site is found east of Redwood Creek. It occurs on uniform to slightly concave slump positions of lower mountain inclines. These mountain slopes are moderately steep to steep.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Mountain slope

(2) Flow |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 614 – 3,232 ft |

| Slope | 15 – 50% |

| Water table depth | 40 – 60 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate is humid with cool, foggy summers and cool, moist winters. Coastal influence limits the diurnal range in temperatures. Summertime temperatures range from 50 to 59 degrees F. The mean annual precipitation ranges from 90 to 100 inches and usually falls from October to May.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 215 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 215 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 95 in |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 4. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 5. Annual average temperature pattern

Influencing water features

There are no influencing water features on this site.

Soil features

These well-drained, very deep soils developed from colluvium derived from earth-flow deposits of mudstone, sandstone and siltstone. They range from moderately to very strongly acidic at 40 inches, with a loamy subsurface and a rock content ranging from non-gravelly to very gravelly.

Soils that have been tentatively correlated to this ecological site include the following:

Soil Survey Area: CA605 - Redwood National and State Parks

MU Component

484 Elkcamp

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Loam |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow |

| Soil depth | 60 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 15% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

5 – 7 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

4.5 – 5.5 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

10 – 35% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

5% |

Ecological dynamics

Historically, prairies within the north coast region were thought to have been dominated by native perennial bunchgrasses and numerous associated forbs (Holland and Keil, 1995). Native Americans utilized the prairies within the Bald Hills for food and cultural materials (Sugihara and Reed, 1987). Regular burning stimulated the growth of grasses and eliminated invading shrubs and trees, thereby attracting wildlife. The use of fire for over 5,000 years by Native Americans created a system in equilibrium that controlled the vegetative structure and composition (Sugihara and Reed, 1987).

With the advent of European settlements, changing land use practices significantly altered the vegetation (Sugihara and Reed, 1987). In the 1800s cattle and sheep grazing became widespread. Increased grazing pressure from domestic livestock and range seeding reduced the native perennials and increased the population of introduced perennials and forbs. More studies are needed to understand grazing and native plant interactions (D'Antonio et al). Shifts in the annual plant community caused by grazing are difficult to document. Certain species will increase with favorable weather and grazing conditions.

Native perennial grasses currently found on this ecological site include blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus), California oatgrass (Danthonia californica), bentgrass (Agrostis spp.), and Canada wildrye (Elymus canadenis). Blue wildrye, a dominant grass on this site, is a native perennial bunchgrass that is found in moist conditions and is favored by disturbances such as burning (Bailey, et al, 1998). Introduced perennial grasses are dominated by bristly dogstail grass (Cynosurus echinatus). Annual grasses that may be found on the site include soft brome (Bromus hordeaceus) and annual vernalgrass (Anthoxanthum aristatum). Perennial forbs may include western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum) and hairy catsear (Hypochaeris radicata).

Non-native grasses often out-compete natives for water, nutrients and growing space (Wilson and Clark, 1998). Tall oatgrass, an introduced perennial within the Bald Hills, is considered an invasive exotic (National Park Service, 2002). One study indicates that early season burning may be more effective in eliminating flowers and developing seeds of tall oatgrass prior to their dispersal (Wilson and Clark, 1998). However, spring burning has a negative effect on the native perennial California oatgrass (National Park Service, 2005). Fall burning has slowed the advance of tall oatgrass within Redwood National Park to some extent (Redwood National Park).

Prescribed burning may favor one species over another. Recent studies indicate that periodic fire may favor perennial species by reducing litter cover and eliminating other plant competition (Huntsinger,et al 1996). Fire may also increase the production of non-natives (Vogl, 1974) and exotic forbs (D'Antonio et al). Long term studies are lacking to evaluate the interaction of prescribed fire, climate, and grazing on both natives and non-native species (D'Antonio et al).

Historically, there was very little overlap between the prairie, oak and conifer systems within the park (Sugihara and Reed, 1987). Fire exclusion in the last century has allowed for the encroachment of shrubs, and in some cases trees, into the prairies. Roads established for harvesting purposes left exposed cut and fill slopes that were rapidly invaded by Douglas-fir. Invasion of prairie and oak woodland by conifers has lead to conversion to forest in a very short period of time (Sugihara and Reed, 1987).

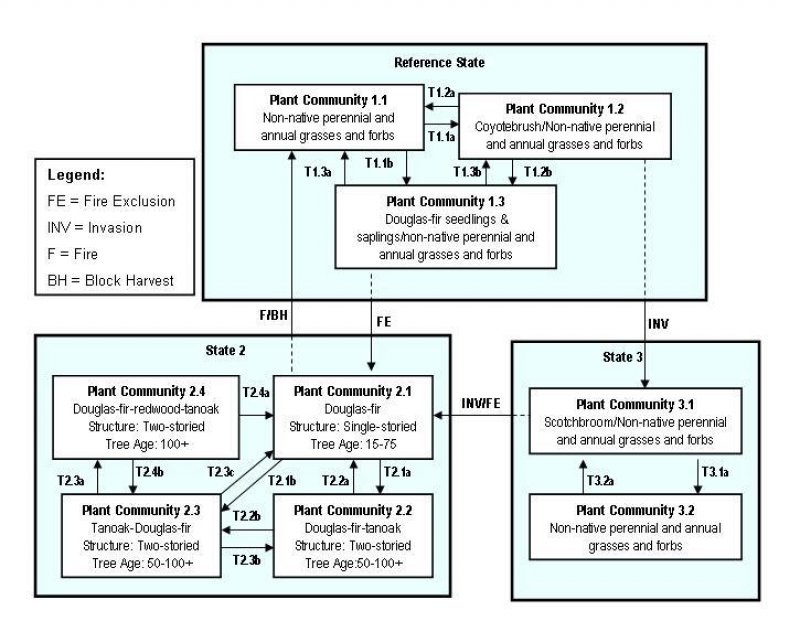

State and transition model

Figure 6. Middle prairie model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 6 submodel, plant communities

State 7 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Native and introduced perennial and annual grasses and forbs

Community 1.1

Native and introduced perennial and annual grasses and forbs

Plant Community 2. The interpretive plant community is dominated by both native and introduced perennial and annual grasses, including bristly dogstail grass (Cynosurus echinatus), soft brome (Bromus hordeaceus), and tall oatgrass (Arrhenatherum elatius). Native perennial grasses present include blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus), California oatgrass (Danthonia californica), and Canada wildrye (Elymus canadensis). 2a) Repeated fire, either natural or prescribed, would tend to perpetuate this community. 2b) The plant community could be altered by uncontrolled grazing or fire exclusion. These factors, either apart or in conjunction, may cause the community to be more heavily dominated by tall oatgrass, bristly dogstail grass, and hairy catsear. Native perennial grasses are still present but their populations are diminished. See PC#3. 2c) Fire exclusion may lead to a gradual invasion of prairie by some brush species, including scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) and coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis), as well as an increase in the annual bristly dogstail grasses. See PC# 4. 2d) With fire exclusion, Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) may gradually invade prairies. Disturbances such a road building or harvesting could expose mineral soil and provide a seedbed for natural regeneration of Douglas-fir. See PC#5.

Forest understory. Species Composition % by weight

bristly dogstail grass 0-29

soft brome 5-54

blue wildrye 5-38

California oatgrass 0-2

Canada wild rye 0-7

annual vernal grass 0-22

western brakenfern 0-9

Total dry weight production:

Favorable year: 6,800 lbs./acre

Normal Year: 4,000 lbs./acre

Unfavorable year: 3,000 lbs./acre

Figure 7. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 3000 | 4000 | 6800 |

| Total | 3000 | 4000 | 6800 |

State 2

Native perennial grasses and forbs

Community 2.1

Native perennial grasses and forbs

Plant Community 1. The historic climax plant community (HCPC) was thought to have been dominated by native perennials that included blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus), California oatgrass (Danthonia californica), bentgrass (Agrostis spp.), and Canada wildrye (Elymus canadensis). The annual forb, miniature lupine (Lupinus bicolor), is also thought to have been common (Arguello, pers. comm.). 1a) Periodic burning by Native Americans maintained the prairies. Blue wildrye, a bunchgrass, is believed to be favored by burning (Johnson, 1999). Lupine species are seed-bankers and respond favorably to fire through the sprouting or germination of buried seed (Meyer, R., 2006). 1b) With the influx of European settlements in the mid-1800s, regular burning of the prairies ceased. Grazing of domestic livestock along with range seeding led to an increase in both the introduced perennial and annual grasses and forbs. These introduced perennials included tall oatgrass (Arrhenatherum elatius). Introduced annuals included bristly dogstail grass (Cynosurus echinatus), soft brome (Bromus hordeaceus), and annual vernalgrass (Anthoxanthum aristatum). Perennial forbs that are present may include western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum) and hairy catsear (Hypochaeris radicata). Native perennials such as blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus) and Canada wildrye (Elymus canadensis) have persisted but in smaller numbers. Important factors in the noted decrease of native species include competition from the more aggressive introduced grasses, as well as the exclusion of fire. 1c) Uncontrolled grazing and fire exclusion are both important factors regarding the dominance of introduced species such as the perennial, tall oatgrass (Arrhenatherum elatius), and bristly dogstail grass (Cynosurus echinatus), which is an introduced annual. Hairy catsear (Hypochaeris radicata), and western brakenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), both perennial forbs, may also be more abundant. Native perennials continue to persist on the site, but their ability to propagate is diminished. See PC#3.

State 3

Introduced perennial and annual grasses and forbs

Community 3.1

Introduced perennial and annual grasses and forbs

Plant Community 3. The plant community is dominated by tall oatgrass (Arrhenatherum elatius), an introduced perennial, as well as the annual, bristly dogstail grass (Cynosurus echinatus). Forbs such as hairy catsear (Hypochaeris radicata) may also be common. 3a) Prescribed fire and mechanical treatments, such as seed drilling, may assist in the reestablishment of some native grasses, though not to historic levels. See PC#2. 3b) Fire exclusion and uncontrolled grazing may gradually infill bare areas with shrubs such as scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) or coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis). Annual grasses and forbs are present in the understory. See PC#4. 3c) Fire exclusion or disturbance may cause this plant community to be gradually invaded by Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). See PC#5.

State 4

Scotch broom-coyotebrush/annual grasses and forbs

Community 4.1

Scotch broom-coyotebrush/annual grasses and forbs

Plant Community 4. This plant community reflects the encroachment of shrubs, including scotch broom (Cystisus scoparius) and coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis). Annual grasses such as bristly dogstail may increase. 4a) Prescribed fire or mechanical treatment, along with seeding of native grasses, could help to reestablish native perennials, though not to historic population levels. See PC#2. 4b) With continued fire exclusion or disturbance, infill of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) from adjacent forest edges is likely. See PC#5.

State 5

Douglas-fir

Community 5.1

Douglas-fir

Plant Community 5. The prairie is infilled with seeds from the adjacent forests creating a dense, single-storied stand of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). 5a) Gradually over time, and with continued fire exclusion, an infill of tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus) may occur in the shade of the conifers. See PC#6. 5b) Management in the early stages of conifer encroachment could temporarily reverse successive progression. Activities could include prescribed fire, tree gridling, or mechanical treatment, in combination with the seeding of native grasses. Periodic fire would be required to keep the prairies free from further conifer infill. See PC#2. 5c) Fire introduced to young Douglas-fir stands could kill the trees and temporarily halt conifer encroachment. See PC#4.

State 6

Douglas-fir-tanoak

Community 6.1

Douglas-fir-tanoak

Plant Community 6. The plant community is dominated by Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) in the overstory and tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus) in the sub-canopy. 6a) If left undisturbed over a long time period, infill of redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) from adjacent forest stands could encroach into the Douglas-fir/tanoak stand. Gradually, redwood would become co-dominant with the Douglas-fir. See PC#7. 6b) Chemical control of tanoak could lead to a stand dominated by Douglas-fir. See PC#5.

State 7

Douglas-fir-redwood-tanoak

Community 7.1

Douglas-fir-redwood-tanoak

Plant Community 7. Gradually, redwood and Douglas-fir become co-dominate in the overstory. Tanoak is present in the sub-canopy. 7a) Following block harvesting or fire, the plant community could be temporarily dominated by Douglas-fir and tanoak. See PC#6.

Additional community tables

Interpretations

Animal community

Roosevelt elk use the prairies for foraging and resting. Other mammals that utilize the prairie edge for foraging or hunting may include: deer, the short and long-tailed weasel, skunk, coyote, badger, bobcat, bear and mountain lion.

Numerous birds rely on grasslands as a feeding habitat, including the red-tailed hawk, turkey vulture, as well as numerous owls and swallow species. Various mice, voles and moles find habitat in grassland and serve as a food source for birds and larger mammals.

Hydrological functions

Runoff class is medium to high.

Hydrologic groups:

Elkcamp -- D

Refer to the Soil Survey Manuscript for further information.

Recreational uses

Recreational use and development may be limited by slopes.

Wood products

There are no wood products associated with the interpretive plant community.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Dry weight transects #05-001R

Other references

Arguello, L.A., 1994. Effects of prescribed burning on two perennial bunchgrasses in the Bald Hills of Redwood National Park. Thesis. Humboldt State University, Arcata, California, USA.

Crane, M. F. 1990. Pteridium aquilinum.

In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2006, November 8].

D'Antonio et al, date?. Ecology and Restoration of California Grasslands with special emphasis on the influence of fire and grazing on native grassland species. University of California, Berkley, CA. 99 pp.

Hatch, D. A., Bartolome, J.W., and Hillyard, D. S., 1991. Testing a management strategy for restoration of California's native grasslands. Pages 343-349. In: Yosemite Centennial symposium proceedings: natural areas and Yosemite, prospects for the future, a global issues symposium joining the 17th annual Areas Conference with the Yosemite Centennial Celebration. National Park Service, California, USA.

Heady, H.F., 1972. Burning and Grasslands in California. Proceedings: Annual Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 12:97-107.

Holland, V. L., and Keil, David J., 1995. California Vegetation. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. 516 pp.

Huntsinger, L., McClaran, M.P., and Bartolome, J., 1996. Defoliation response and growth of Nassela pulchra (A.Hitchc.) Barkworth from serpentine and non-serpentine grasslands. Madrono 43:46-57.

Keeley, J.E., 1981. Reproductive cycles and fire regimes. Pages 231-277. In: Mooney H.A. et al, editors. Proceedings of the conference on fire regimes and ecosystem properties. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, General Technical Report WO-26.

Meyer, Rachelle. 2006. Lupinus perennis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ (2006, September 26).

Murphy , D.D. and Erlick, P.R., 1989. Conservation biology of California's remnant native grasslands. Pages 201-211 in Huenneke, L.F., and H.A. Mooney, ediots. Grassland structure and function: California annual grassland. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

National Park Service, 2002. High Priority Invasive Plant Species: Threats posed and where the plants occur in the parks, http:/www.nps.gov/redw/priority.htm (August 22,2006)

National Park Service, 2005. Integrated managment strategies used to protect the cultural landscape of Bald Hills. In: Natural Resource year in Review-2005. http://www2.nature.nps.gov/Year in Review/02_D.html. (August, 2006)

Page, C. N. 1986. The strategies of bracken as a permanent ecological opportunist. In: Smith, R. T.; Taylor, J. A., eds. Bracken: ecology, land use and control technology; 1985 July 1 - July 5; Leeds, England. Lancs: The Parthenon Publishing Group Limited: 173-181. [9721]

Steinberg, Peter D. 2002. Baccharis pilularis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2006, November 8].

Sugihara, Neil G., and Reed, Lois J., 1987. Vegetation Ecology of the Bald Hills Oak Woodlands of Redwood National Park, Redwood National Park Research and Development, Technical Report 21.

Tappeiner, John C., II; McDonald. P.M.; Hughes, T.F. 1986. Survival of tanoak (LIthocarpus densiflorus) and Pacific madrone (Arbutus menziesii) seeedlings in forests of southwestern Oregon. New Forests. 1: 43-55.

Vogl, R.J. 1974. Effects of Fire on Grasslands. Pages 139-194 in Kozlowski, T.T. and Ahlgren, C.E., editors. Fire and Ecosystems. Academic press, Inc. London, United Kingdom.

Wilson, Mark V., and Clark, Deborah L., 1998. Recommendations for Control of Tall Oatgrass, Poison oak and Rose in Willamette Valley Upland Prairies. Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University. 12 pp.

Zouhar, Kris. 2005. Cytisus scoparius, C. striatus. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2006, November 29].

Contributors

Judy Welles

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.