Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R008XY536WA

Loamy South Aspect Columbia Hills

Last updated: 5/23/2025

Accessed: 12/18/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 008X–Columbia Plateau

MLRA 8 encompasses about 50,100 square kilometers mainly in Washington and Oregon, with a small area in Idaho. This MLRA is characterized by loess hills, surrounding scablands, and alluvial deposits. This MLRA consists mostly of Miocene Columbia River Basalt covered with up to 200 feet of loess and volcanic ash. The dominant soil order in this MLRA is Mollisols. Soils in this MLRA dominantly have a mesic temperature regime, a xeric moisture regime, and mixed minerology.

Classification relationships

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 8 – Columbia Plateau

LRU – Common Resource Areas (CRA):

8.5 - Moist Yakima Folds

Ecological site concept

Note: For MLRA 8 there are four ecological sites with the name ‘Loamy’.

1. One for the sagebrush steppe region

2. One specifically for grasslands on Goldendale Prairie (Klickitat Co.)

3. One specifically for grasslands on south side of Columbia Hills (Klickitat Co.)

4. One for other grassland regions in MLRA 8 including

a. SE portion of MLRA 8 includes portions of Adams, Franklin, Walla Walla, Asotin, Columbia and Garfield counties

b. Area above Coulee Dam in Douglas Co.

The Loamy ESD below is for grasslands on the south side of Columbia Hills in Klickitat Co. (see 3 above).

Diagnostics:

The soils for this grassland steppe upland site are 20 inches & deeper with a loamy surface texture and limited rock fragments (generally 10 percent or less) in the root-growing portions of the soil profile. Silt loam is most common, but a variety of soils and landforms are possible.

Note: due to historic farming and grazing the south side of the Columbia Hills has been heavily disturbed. No pristine remnant is known, so the reference state has been reconstructed based on experience in MLRA 8.

The south side of the Columbia Hills is a grassland steppe area and has not had sagebrush for more than 50 years and is not expected to have sagebrush. This area does not have sagebrush, nor bitterbrush, and no rabbitbrush except for one small area near the Columbia River.

Perennial bunchgrasses would dominate the reference state. Cool-season bunchgrasses form two distinct layers. Bluebunch wheatgrass is the dominant bunchgrass in the top grass layer, while Sandberg bluegrass is the major grass of the lower grass layer. Native forbs fill the interspaces.

Principle Vegetative Drivers:

The moderately deep to deep silt loam soils and the south aspect drive the vegetative expression of this productive site. Most species have unrestricted rooting on this site.

Associated Sites:

Loamy, south aspect, Columbia Hills is associated with other ecological sites in the grassland steppe areas of MLRA 8, including Shallow Stony and Shallow Sand. Very Shallow may also be nearby.

Similar Sites:

Loamy, south aspect, Columbia Hills on south side of Columbia Hills is a bluebunch wheatgrass site. Shrubs and Idaho fescue are nonexistent. The other Loamy ecological sites in MLRA 8 Columbia Plateau have sagebrush or Idaho fescue.

Associated sites

| R008XY516WA |

Shallow Stony South Aspect Columbia Hills |

|---|---|

| R008XY546WA |

Sand South Aspect Columbia Hills |

| R008XY001WA |

Very Shallow |

Similar sites

| R008XY435WA |

Loamy 14-20 PZ Goldendale Prairie |

|---|---|

| R008XY455WA |

Loamy North Aspect 14-20 PZ Goldendale Prairie |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Pseudoroegneria spicata |

Physiographic features

The landscape is part of the Columbia basalt plateau. Loamy, south aspect, Columbia Hills sites occur on broad ridges and plateaus, stream terraces, and east-facing hillslopes of the Columbia Hills in Klickitat County.

Physiographic Division: Intermontane Plateau

Physiographic Province: Columbia Plateau

Physiographic Sections: Walla Walla Plateau Section

Landscapes: Hills and plateaus

Landform: Sideslopes

Aspect: Dominantly southern aspects, but can occur on all aspects

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Geomorphic position, hills |

(1) Side Slope |

|---|---|

| Landforms |

(1)

Hills

(2) Plateau (3) Hillslope |

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 91 – 853 m |

| Slope | 10 – 50% |

| Water table depth | 152 cm |

| Aspect | W, NW, N, NE, E, SE, S, SW |

Table 3. Representative physiographic features (actual ranges)

| Flooding frequency | Not specified |

|---|---|

| Ponding frequency | Not specified |

| Elevation | 91 – 975 m |

| Slope | 0 – 65% |

| Water table depth | Not specified |

Climatic features

Grasslands do not have shrubs because they receive more spring precipitation especially in March (Daubenmire). The climate is characterized by moderately cold, wet winters, and hot, dry summers, with limited precipitation due to the rain shadow effect of the Cascades. Winter fog is variable and often quite localized, as the fog settles on some areas but not others. Compared to the rest of MLRA 8, the south side of the Columbia Hills is dry and hot. Taxonomic soil climate is xeric moisture regime with a mesic temperature regime.

Table 4. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 120-150 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 254-356 mm |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 110-160 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | |

| Precipitation total (actual range) |

Influencing water features

A plant’s ability to grow on a site and overall plant production is determined by soil-water-plant relationships

1. Whether rain and melting snow run off-site or infiltrates into the soil

2. Whether soil conditions remain aerobic or become saturated and become anaerobic

3. Water drainage and how quickly the soil reaches the wilting point

With adequate cover of live plants and litter, there are no restrictions on Loamy sites with water infiltrating into the soil. These sites are well drained and are saturated for only a short period.

Soil features

This ecological site components are dominantly Ultic and Typic taxonomic subgroups of Argixerolls and Haploxerolls great groups of the Mollisols taxonomic order. Soils are moderately deep to very deep. Average available water capacity of about six inches (15.2 cm) in the zero to 40 inches (zero to 100 cm) depth range.

Soil parent material is dominantly mixed loess over colluvium and residuum.

The associated soils are Fisherhill, Stacker, Walla Walla and similar soils.

Dominate soil surface is silt loam.

Dominant particle-size class is fine-loamy to coarse-silty.

Table 5. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Loess

(2) Colluvium (3) Residuum |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Silt loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Fine-loamy (2) Coarse-silty |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Depth to restrictive layer | 51 – 152 cm |

| Soil depth | 152 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 1% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

15.24 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (Depth not specified) |

0 – 5% |

| Electrical conductivity (Depth not specified) |

0 – 2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (Depth not specified) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-25.4cm) |

6.1 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

2% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

1% |

Table 6. Representative soil features (actual values)

| Drainage class | Not specified |

|---|---|

| Depth to restrictive layer | Not specified |

| Soil depth | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 5% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0 – 5% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

12.45 – 21.08 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

| Electrical conductivity (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-25.4cm) |

Not specified |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 15% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 10% |

Ecological dynamics

Loamy South Aspect Columbia Hills produces about 600 to 900 pounds/acre of biomass annually.

The line between sagebrush steppe and true grasslands has been discussed and debated for many years. Daubenmire states that the line has nothing to do with pre-settlement as native ungulates played no significant role in the evolution of ecotypes. He also says that there is no evidence that the distribution of vegetative types is related to fire. And he also says there is no useful correlation between soil classification and the line between grasslands and sagebrush steppe.

The ecotones between Daubenmire’s vegetation types can be defined on the basis of consistent differences in climate and consistent differences in vegetation. Higher spring precipitation, especially in March, favors grasses over sagebrush. The grassland area of southeastern Adams and eastern Franklin counties have more precipitation in March. The same for the grasslands in Walla Walla, Asotin and Garfield counties. The Goldendale Prairie and the high elevation grassland above Coulee Dam in Douglas county also have higher spring precipitation. So, the grassland areas of MLRA 8 are consistent with Daubenmire’s findings.

Bluebunch wheatgrass would be dominant in the reference state. It is a long-lived, mid-sized cool-season bunchgrass with an awned or awnless seed head arranged in a spike. Bluebunch provides a crucial and extensive network of roots to the upper portions (up to 48” deep in soils with no root-restrictive horizons) of the soil profile. These roots create a massive underground source to stabilize the soils, provide organic matter and nutrients inputs, and help maintain soil pore space for water infiltration and water retention in the soil profile. The extensive rooting system of mid-sized bunchgrasses leave very little soil niche space available for invasion by other species. This drought resistant root can compete with, and, suppress the spread of exotic weeds.

The stability and resiliency of the reference communities is directly linked to the health and vigor of bluebunch wheatgrass. Refer to page 8 for more details about bluebunch physiology. Research has found that the community remains resistant to medusahead if the site maintains at least 0.8 mid-sized bunchgrass plant/sq. ft. (K. Davies, 2008). It is bluebunch that holds the system together. If we lose the bluebunch the ecosystem crashes or unravels.

The natural disturbance regime for grassland communities is periodic lightning-caused fires. The fire return intervals (FRI) listed in research for sagebrush steppe communities is quite variable. Ponderosa pine communities have the shortest FRI of about 10 to 20 years (Miller). The FRI increases as one moves to wetter forested sites or to dries shrub steppe

communities. Given the uncertainties and opinions or reviewers, a mean of 75 years was chosen for sagebrush steppe (Rapid Assessment Model). This would place the historic FRI for grassland steppe around 30 to 50 years.

The effect of fire on the community depends upon the severity of the burn. With a light to moderate fire there can be a mosaic of burned and unburned patches. Bunchgrasses thrive as the fire does not get into the crown. With adequate soil moisture bluebunch wheatgrass can make tremendous growth the year after the fire. Largely, the community is not affected by lower intensity fire. Needle and thread is one native species that can increase via new seedlings following a fire.

A severe fire puts stress on the entire community. Spots and areas that were completely sterilized are especially vulnerable to exotic invasive species. Sterilized spots must be seeded to prevent invasive species (annual grasses, tumble mustard) from totally occupying the site. Bluebunch wheatgrass and basin wildrye will have weak vigor for a few years but generally survive.

Grazing is another common disturbance that occurs to this ecological site. Grazing pressure can be defined as heavy grazing intensity, or frequent grazing during reproductive growth, or season-long grazing (the same plants grazed more than once). As grazing pressure increases the plant community unravels in stages:

1. Bluebunch wheatgrass declines while Sandberg bluegrass and needle and thread increase

2. As bluebunch wheatgrass continues to decline, invasive species such as cheatgrass and knapweed colonize the site

3. With further decline the site can become a cheatgrass community

Managing grasslands to improve the vigor and health of native bunchgrasses begins with an understanding of grass physiology. New growth each year begins from basal buds. Bluebunch wheatgrass plants rely principally on tillering, rather than establishment of new plants through natural reseeding. During seed formation, the growing points become elevated and are vulnerable to damage or removal.

If defoliated during the formation of seeds, bluebunch wheatgrass has limited capacity to tiller compared with other, more grazing resistant grasses (Caldwell et al., 1981). Repeated critical period grazing (boot stage through seed formation) is especially damaging. Over several years each native bunchgrass pasture should be rested during the critical period two out of every three years (approximately April 15 to July 15). And each pasture should be rested the entire growing season every third year (approximately March 1 to July 15).

In the spring each year it is important to monitor and maintain an adequate top growth: (1) so plants have enough energy to replace basal buds annually, (2) to optimize regrowth following spring grazing, and (3) to protect the elevated growing points of bluebunch wheatgrass.

Bluebunch wheatgrass remains competitive if:

(1) Basal buds are replaced annually,

(2) Enough top-growth is maintained for growth and protection of growing points, and

(3) The timing of grazing and non-grazing is managed over a several-year period. Careful management of late spring grazing is especially critical

For more grazing management information refer to Range Technical Notes found in Section I Reference Lists of NRCS Field Office Technical Guide for Washington State.

In Washington, bluebunch wheatgrass communities provide habitat for a variety of upland wildlife species.

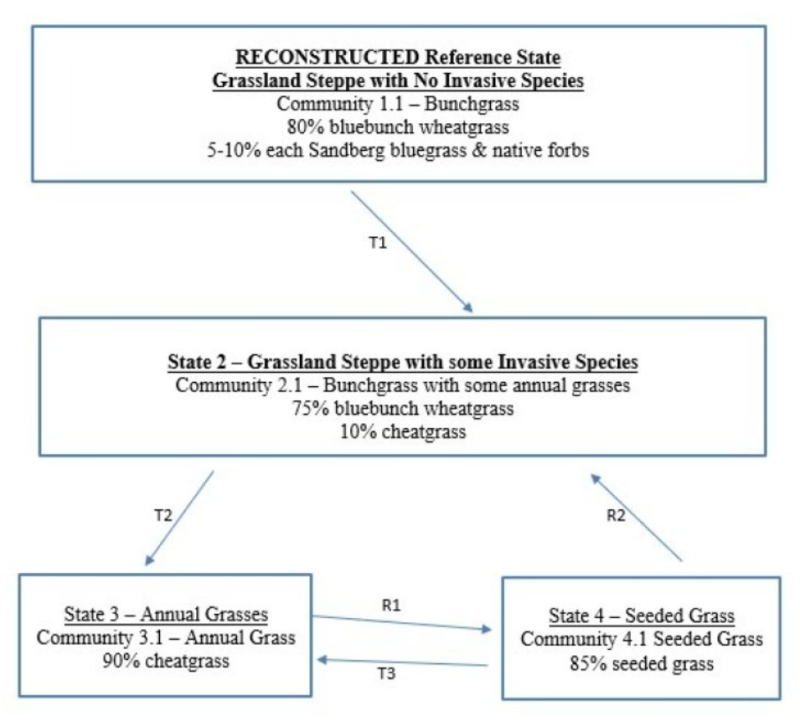

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Historic Reference - Grassland Steppe with No Invasive Species

Note: most Loamy sites on the south side of the Columbia Hills have already crossed the threshold into State 3 State 1 Narrative: State 1 represents grassland steppe with no invasive or exotic weed species. Each functional, structural group would have one or more native species. The south side of the Columbia Hills has no sagebrush or bitterbrush, and except for a spot along the Columbia River, the south side of the Columbia Hills also has no rabbitbrush. Reference State Community Phases: 1.1 Bunchgrass Bluebunch wheatgrass Dominate Reference State Species: would be bluebunch wheatgrass At-risk Communities: • Any community in the reference state is at risk of moving to State 2. The seed source of cheatgrass is nearby and blowing onto most sites annually.

Community 1.1

Bluebunch Wheatgrass, Sandberg Bluegrass, and Native Forbs

80% bluebunch wheatgrass 5-10% Sandberg bluegrass 5-10% native forbs

Figure 1. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

State 2

Current Potential - Grassland Steppe with Some Invasive Species

Note: most Loamy sites on the south side of the Columbia Hills have already crossed the threshold into State 3 State 2 Narrative: State 2 represents native grassland steppe with minor inclusion of invasive annual grasses such as cheatgrass. All the native functional, structural groups would be represented by one or more species. Cheatgrass would be a minor component in State 2. Once a community has been invaded by cheatgrass the chance of going back to State 1 is small. Community Phases for State 2: 2.1 Bunchgrass Bluebunch wheatgrass

Community 2.1

Bluebunch Wheatgrass and Cheatgrass

75% bluebunch wheatgrass 10% cheatgrass

State 3

Annual Grasses

Note: most Loamy sites on the south side of the Columbia Hills have already crossed the threshold into State 3 State 3 Narrative: State 3 represents sites dominated by invasive annual species and has crossed a biological threshold. As State 1 or State 2 begins to unravel the dominant bunchgrasses decline while invasive grasses become more and more prominent. Virtually all the native functional, structural groups are missing in State 3. Community Phases for State 3: 3.1 Annual Grass cheatgrass

Community 3.1

Annual Grasses

Dominant Species: Annual grasses such as cheatgrass. The main species can include other annual bromes, medusahead, ventenata, mustard, prickly lettuce and diffuse knapweed. 90% cheatgrass

State 4

Seeded Grass

State 4 represents a site that has been seeded to desirable grasses such as Secar Snake River wheatgrass, Sherman big bluegrass, or crested wheatgrass. State 4 is stable if 0.8 plant per sq. ft. or greater of the desired bunchgrasses is maintained. Community Phases for State 4: 4.1 Seeded Grasses

Community 4.1

Seeded Grass

85% seeded grass

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Result: transition from Reference State to State 2 (grassland steppe w/ a few annuals). The Reference State does not have invasive species. State 2 is the same as Reference State but with minor addition of invasive annual grasses such as cheatgrass. Primary Trigger: soil disturbances (rodents, badgers) create openings in the community or a high moisture year causes a micro-burst of cheatgrass and is the principle means of colonization. Loss of soil biological crusts contribute to the invasion. Ecological process. Annually cheatgrass or other annual grass seed blows onto most Reference State sites. With seed-soil contact this seed germinates and competes with the native species for space, light and moisture. The loss of soil biological crusts also contributes to the invasion. Even pristine communities in the Reference State are susceptible to colonization by invasive annual grasses. Indicators: The occurrence of annual grasses on sites where they had been absent.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Result: shift from State 2 with a few annuals to State 3 which is dominated by annual grasses. This transition would occur once the cover of bluebunch wheatgrass declines to less than 10% and invasive species cover is greater than 40%. Primary Trigger: Due to chronic heavy grazing, season-long grazing, or late spring grazing, dominant species are all but eliminated. Annuals such as cheatgrass have gained the competitive advantage. The site has lost its primary species that stabilize and protect the soil from wind and water erosion and has also lost the ability to retain sufficient soil moisture for many of the native perennial species. Note: chronic season-long grazing in 1880s-1940s created thousands of acres of annual grass-sagebrush community, and then fire turned that into annual grasses. Ecological process: the unraveling of the native plant community begins with consistent defoliation pressures to bluebunch wheatgrass. This causes poor vigor, shrinking crowns and plant mortality. With more and more of the soil surface and upper soil rooting surfaces open, opportunistic weeds that take advantage of the available niche space and expand. The invasive annual grasses in State 2 communities make a dramatic increase to dominate the community. Secondary Trigger: Repeated fire does the same thing. In Washington, chronic season-long grazing caused more acres of State 2 than repeated fire. Repeated fire is a much more common event in south Central Washington than elsewhere in MLRA 8. Indicators: Decreasing vigor and cover of bluebunch wheatgrass and increasing cover of invasive annual species. Increasing distance between perennial species. Decreasing soil organic matter, soil water retention, limited water infiltration and percolation in the soil profile.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 4

This restoration transition does not occur without significant time and inputs to control weeds, prepare a seedbed, seed desirable species, and post-seeding weed control and management. This requires a commitment of two years or more for weed control. Care must be taken to maintain soil structure so that the seedbed has many safe-sites for the seed. Seed placement must be managed to achieve seed-soil contact at very shallow depth (about 1/8 inch is desired). Proper grazing management is essential to maintain the stand post-seeding. Secar Snake River wheatgrass, thickspike wheatgrass, Sherman big bluegrass, Sandberg bluegrass, and intermediate wheatgrass are typical species seeded on Loamy ecological site. The actual transition occurs when the seeded species have successfully established and are outcompeting the annual species for cover and dominance of resources.

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 2

Result: Shift from State 4 back to State 2. This restoration transition does not occur without a significant commitment of time & resource inputs to restore ecological processes, native bunchgrasses and native forb species. Attention needs to be paid to each step of the process: weed control, seedbed preparation, seeding and planting operations and post-seeding management. Shifting from State 3 to State 4 to State 2: If the goal is to restore back to a native plant community, State 3 must first be shifted to State 4. It will take two years or longer to kill annual species and to exhaust the seedbank of invasive species. Site will then need to be seeded to perennial species such as Snake River wheatgrass to restore soil properties before native species can survive and thrive on site. The seeded species rebuild some of the basic soil properties including increased soil organic matter, increased soil moisture, and likely would also require the soil’s pore spaces, bulk density and soil microorganisms to return before the native species that used to survive in this ecological site can return. The site would also need several years with no significant fires and proper grazing management as well. See narrative for R1A transition above. Shifting from State 4 to State 2: This assumes that the shift from State 3 to State 4 has been successful. State 4 stand must be killed before proceeding. The seeding of native species should occur in two steps: (1) a seeding of native bunchgrasses so that broadleaf weeds may be controlled, (2) a re-introduction of native forbs. The site would also need several years of no significant fires and proper grazing management as well to ensure plant establishment and vigor.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 3

Result: shift from seeded grass State 4 to State 3 which is dominated by invasive annual species. This transition occurs when the desirable seeded grasses become minor to the dominant annual grasses. Primary Trigger: This transition occurs when chronic heavy grazing has removed too much of the perennial bunchgrass cover allowing invasive annual species to colonize the site. As this continues the competitive advantage goes to the exotic species which are opportunistic and take most of the site’s resources. Little of the resources remain for the desirable species. Secondary Trigger: Frequent fires or a severe fire that removes too much of the perennial bunchgrass cover and gives the competitive advantage back to the invasive species. Ecological process: the unraveling of the seeded grass community begins with consistent defoliation pressures to seeded grasses. This causes poor vigor, shrinking crowns and plant mortality. With more and more of the soil surface and upper soil rooting surfaces open, opportunistic weeds that take advantage of the available niche space and expand. The invasive annual grasses in State 2 communities make a dramatic increase to dominate the community. Indicators: shrinking crowns and mortality of desirable species, increasing caps gaps between desirable perennial species, increasing cover by annual grasses.

Additional community tables

Table 7. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 1 | Sprouting Shrubs - Minor | 34– | ||||

| currant | RIBES | Ribes | – | – | ||

| rose | ROSA5 | Rosa | – | – | ||

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 2 | Dominant Mid-Size Bunchgrasses | 785– | ||||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | – | – | ||

| 3 | Other Mid-Size Bunchgrasses - Minor | 34– | ||||

| squirreltail | ELEL5 | Elymus elymoides | – | – | ||

| Thurber's needlegrass | ACTH7 | Achnatherum thurberianum | – | – | ||

| needle and thread | HECO26 | Hesperostipa comata | – | – | ||

| Columbia needlegrass | ACNE9 | Achnatherum nelsonii | – | – | ||

| 4 | Short Grasses - Minor | 112– | ||||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | – | – | ||

| sixweeks fescue | VUOC | Vulpia octoflora | – | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 5 | Native Forbs - Minor | 112– | ||||

| arrowleaf balsamroot | BASA3 | Balsamorhiza sagittata | – | – | ||

| lupine | LUPIN | Lupinus | – | – | ||

| hawksbeard | CREPI | Crepis | – | – | ||

| longleaf phlox | PHLO2 | Phlox longifolia | – | – | ||

| spiny phlox | PHHO | Phlox hoodii | – | – | ||

| granite prickly phlox | LIPU11 | Linanthus pungens | – | – | ||

| buckwheat | ERIOG | Eriogonum | – | – | ||

| Indian paintbrush | CASTI2 | Castilleja | – | – | ||

| common yarrow | ACMI2 | Achillea millefolium | – | – | ||

| trumpet | COLLO | Collomia | – | – | ||

| yellow fritillary | FRPU2 | Fritillaria pudica | – | – | ||

| desertparsley | LOMAT | Lomatium | – | – | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | – | – | ||

| fleabane | ERIGE2 | Erigeron | – | – | ||

| hawkweed | HIERA | Hieracium | – | – | ||

| woolly plantain | PLPA2 | Plantago patagonica | – | – | ||

| silverpuffs | MICRO6 | Microseris | – | – | ||

| western stoneseed | LIRU4 | Lithospermum ruderale | – | – | ||

| mariposa lily | CALOC | Calochortus | – | – | ||

| low pussytoes | ANDI2 | Antennaria dimorpha | – | – | ||

| larkspur | DELPH | Delphinium | – | – | ||

Interpretations

Supporting information

Other references

Boling M., Frazier B., Busacca, A., General Soil Map of Washington, Washington State University, 1998

Daubenmire, R., Steppe Vegetation of Washington, EB1446, March 1968 Davies, Kirk, Medusahead Dispersal and Establishment in Sagebrush Steppe Plant Communities, Rangeland Ecology & Management, 2008

Environmental Protection Agency, map of Level III and IV Ecoregions of Washington, June 2010

Miller, Baisan, Rose and Pacioretty, “Pre and Post Settlement Fire regimes in mountain Sagebrush communities: The Northern Intermountain Region Natural Resources Conservation Service, map of Common Resource Areas of Washington, 2003

Rapid Assessment Reference Condition Model for Wyoming sagebrush LANDFIRE project, 2008

Rocchio, Joseph & Crawford, Rex C., Ecological Systems of Washington State. A Guide to Identification. Washington State Department of Natural Resources, October 2015. Pages 156-161 Inter-Mountain Basin Big Sagebrush.

Rouse, Gerald, MLRA 8 Ecological Sites as referenced from Natural Resources Conservation Service-Washington FOTG, 2004

Soil Conservation Service, Range Sites for MLRA 8 from 1980s and 1990s Tart, D., Kelley, P., and Schlafly, P., Rangeland Vegetation of the Yakima Indian reservation, August 1987, YIN Soil and Vegetation Survey

Contributors

Kevin Guinn

Acknowledgments

Provisional Site Author: Kevin Guinn

Technical Team: K. Moseley, G. Fults, R. Fleenor, W. Keller, C. Smith, K. Bomberger, C. Gaines, K. Paup-Lefferts

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 05/08/2025 |

| Approved by | Kirt Walstad |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.