Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R019XI100CA

Loamy slopes 13-31" p.z.

Accessed: 03/14/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

Similar sites

| R019XI113CA |

Loamy volcanic slopes 13-24" p.z. This coastal sagebrush-buckwheat site is found on volcanic soils with a higher species diversity. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Artemisia californica |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Nassella pulchra |

Physiographic features

This ecological site is located on coastal hills, canyons, and alluvial fans on slopes ranging from 0 to 75 percent, with the most common slopes ranging from 30 to 75 percent. Elevations are most common from just above sea level to approximately 1500 feet. It is found on all aspects, but favors south-facing slopes.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hill

(2) Canyon (3) Alluvial fan |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 10 – 1,500 ft |

| Slope | 30 – 75% |

| Aspect | SE, S, W |

Climatic features

This ecological site is found on two of the five northern Channel Islands, Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa. Each island has a different temperature and precipitation range, however for the purposes of this description, they have all been added together to capture the entire range of variance.

The average annual precipitation is 26 inches with a range between 13 to 31 inches, mostly from rain in the winter months from November through April. The average annual air temperature is between 56 and 73 degrees Fahrenheit, and the frost-free (>32F) season is 320 to 365 days.

NOTE: Data collected for monthly precipitation and temperatures is only from one climate station/island, and is averaged between both islands, therefore may not capture the variance in climates on each of the five islands.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 365 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 31 in |

Figure 2. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Influencing water features

This site is not influenced by wetland or riparian water features.

Soil features

This ecological site is found on several soil components. These soils have developed from colluvium derived from shale, diorite siltstone and/or residuum weathered from clayey shale or gabbro.

The surface and subsurface textures are highly varied. Many of the soils for the ecological site are mollisols with an argillic horizon, and most are shallow or moderately deep to bedrock. Mean annual soil temperatures (MAST) range between 59 and 71 degrees F, and are classified as thermic.

This ecological site occurs on the following soil components in the Channel Islands Soil Survey.

Mu Area Map symbol Component

CA688 180 Typic Argixerolls

CA688 200 Fantail-Thin Surface

CA688 200 Fantail

CA688 210 Lospinos

CA688 211 Lospinos

CA688 212 Lospinos

CA688 230 Fantail

CA688 262 Fantail

CA688 262 Halyard

CA688 292 Bouy

CA688 310 Livigne

CA688 311 Livigne

CA688 680 Bireme

CA688 681 Bireme

CA688 710 Typic Xerorthents

CA688 710 Buoy

CA688 711 Typic Haploxeralfs

CA688 712 Buoy

CA688 721 Buoy

CA688 722 Buoy-Cobbely

CA688 723 Buoy

CA688 724 Buoy

CA688 725 Buoy

CA688 730 Buoy

CA688 761 Typic Xerorthents

CA688 763 Buoy

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Very gravelly (2) Very gravelly (3) Extremely gravelly |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Moderately well drained to somewhat excessively drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow to moderate |

| Soil depth | 2 – 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 5 – 40% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 35% |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

0.2 – 5.1 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

1 – 6% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

5.1 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

5 – 80% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

1 – 20% |

Ecological dynamics

The historical and potential natural community for this ecological site is the coastal sagebrush (Artemisia californica) community. This community is characterized by a relatively dense cover of coastal sagebrush with Santa Cruz Island buckwheat (Eriogenum arborescens) and other native shrubs, forbs, and perennial grasses. The historical community has been severely impacted and altered since Anglo-European settlement. Much of the area which historically was coastal sagebrush has been altered to the non-native annual grassland state. Natural states within this community include a coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis)-dominated state, a native annual state, and a forb state. Several factors have promoted the transition to the non-native annual grassland state, primarily the introduction of non-native Mediterranean species, severe overgrazing by introduced livestock, and a change in the fire regime. There is currently a debate as to whether the non-native annual grassland should be treated as a state of the coastal sagebrush community, or if has it crossed a threshold to become its own new plant community. For this ecological site it will be treated as a state, because coastal sagebrush appears to be recovering in many areas.

During the mid 1800s and the early 1900s the Channel Islands were heavily impacted by grazing from sheep, goats, cattle, horses, and pigs. Livestock may have been brought to Santa Rosa Island as early as 1805. The first cattle were brought to Santa Cruz Island in 1830 to support 100 exiled Mexican convicts. Ranching began in 1839 with the first private land owner, Andres Castillero. By 1853 the Santa Cruz Island Ranch had a good reputation for its well-bred, healthy Merino sheep. The sheep population steadily increased as they began to roam wild. Their population was estimated to be over 50,000 between 1870 and 1885, and up to 100,000 by 1890. In 1939, as a response to their detrimental effects to the island, 35,000 sheep were rounded up for sale to the mainland and efforts began to eliminate the sheep. An estimated 180,000 sheep were shot during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1987 The Nature Conservancy became the sole owner of the western 90 percent of Santa Cruz Island. They continued to eliminate the sheep, and also began removing cattle from the island. Pigs were reportedly introduced to the island in 1853, and by 1854 were roaming freely. The pigs are currently being eliminated section by section from Santa Cruz Island. (Junak et al., 1995). Many acres were cultivated for various crops, but primarily for hay production. In 1922, 800 acres of hay were cultivated at Christi Ranch, Scorpion Ranch, and near Prisoners Harbor (Junak et al., 1995).

A study of the pollen in soil cores taken from an estuary on Santa Rosa Island reveal dramatic changes since the 1800s (Cole and Liu, 1994). The pollen analysis shows an increase in grass pollen more than double any period recorded in the prior 5000 years. It was suggested this could be due to the introduction of non-native annual grasses. The decline of grass pollen coincides with the introduction of large numbers of grazing livestock in the 1840s. Charcoal fragments also increased at this time, possibly attributed to ranchers burning areas to clear brush or an increased fire potential from the annual grasses. The first stork’s bill (Erodium) pollen was dated to 1850, with a peak in 1894. The non-native stork’s bill thrives on disturbed bare soil. A peak in fungal spores between 1874 and 1894 coincides with the peak in soil erosion and the sheep population. (Cole and Liu, 1994)

The heavy grazing of the livestock on the coastal sagebrush leaves and shoots led to a lack of leaf area to support photosynthesis, which eventually caused the death of many shrubs. The livestock also ate the flowers and seeds, reducing the chance of reproduction. The lack of vegetative cover and trampling by hooves caused severe erosion over most of the island. Much of the nutrient rich topsoil was lost and replaced with shallower soils and harsh subsurface soils. These combined factors reduced the area covered by sagebrush, and enabled the invasion of annual grasses. However, comparison photos from Santa Cruz Island during the years of grazing and the years since show recovery of sagebrush in many areas, particularly on canyon sideslopes (Lyndal L. Laughrin, Ph.D. personal photos).

A study was done concerning the suppression of sagebrush by annual grasses (Eliason and Allen, 1997). It stated that the coastal sagebrush had difficulty competing with the non-native grasses during germination and the first season of growth. The most limiting resource was most likely water. Annual grasses tend to utilize soil water earlier in the season, leaving the soil depleted for the sagebrush. By the second year the grasses had less affect on the sagebrush. The study notes that succession back to sagebrush may be inhibited by the grasses, but restoration by planting young plants or by the removal of the grasses then reseeding, may be successful. The main problem when restoring coastal sagebrush shrubland is the issue of how to regain the biodiversity in the area. (Allen et al.)

Coyotebrush is often the first shrub to re-establish in the non-native annual grasslands. It does best in full sun on bare soil, such as eroded areas or sand dunes. Coyotebrush can develop into large patches and persist for many years. It tends to shade out the annual grasses, creating a suitable habitat for sagebrush seedling development. The sagebrush can eventually dominate because the coyotebrush does not regenerate well under the canopy of sagebrush (Steinburg, 2002).

The normal (or natural) fire interval for coastal sagebrush on the mainland is about 25 to 30 years (Allen et al,; Keeley and Keeley 1984). Due to the nature of the storms in that area, lightning initiated fires tend to be less frequent on the islands than on the mainland. The use of fire by Native Americans and its affect on the pattern of sagebrush and grassland communities is unclear (Keeley, 2002). The Chumash Indians lived on, and visited many of Channel Islands. Records show habitation for more than 6000 years, with an estimate of about 2000 people living on Santa Cruz Island in 1542. It is believed that fire was used in the coastal mountains of California to clear shrublands in favor of grasslands (Keeley, 2002). It is likely this practice was used to some extent on the Channel Islands as well.

The coastal sagebrush community is somewhat adapted to fire. Many of the shrub species in this community have the ability to resprout after moderate fires. After fire, annuals and perennials dominate for a couple of years. Shrubs will resprout within the first year and produce prolific seeds the second year. Through resprouting and seeding, the shrubs will begin to re-establish in the area and should regain dominance by the third year.

Some studies suggest that if fire frequency becomes less than 5 to 10 years, the sagebrush shrubs cannot regenerate and annual grasses will dominate (Minnich and Scott). The non-native grasses have created a continuous fuel layer that did not exist before, which can quickly ignite and spread. The mixture of annual grasses within the sagebrush community has also increased the flammability and severity of fires within the existing sagebrush patches. Fire frequency has increased due to the intentional setting of fires during the ranching years, and because of accidental fires. Fire may be more frequent than in the past, but fire suppression efforts may counterbalance the increased ignition rate.

Coastal sagebrush restoration is possible, with some degree of energy inputs and depending on how diminished the sagebrush cover has become. The most successful restoration technique, especially in heavily dominated stands of non-native annual grasses, is to plant established sagebrush plants instead of attempting to reseed the species. This will ensure that the sagebrush gains a competitive edge over the annual grasses for the necessary resources (Bowler 2000). Other techniques might include burning, then disking and seeding native grasses and forbs, and two years later, going back through and seeding in sagebrush.

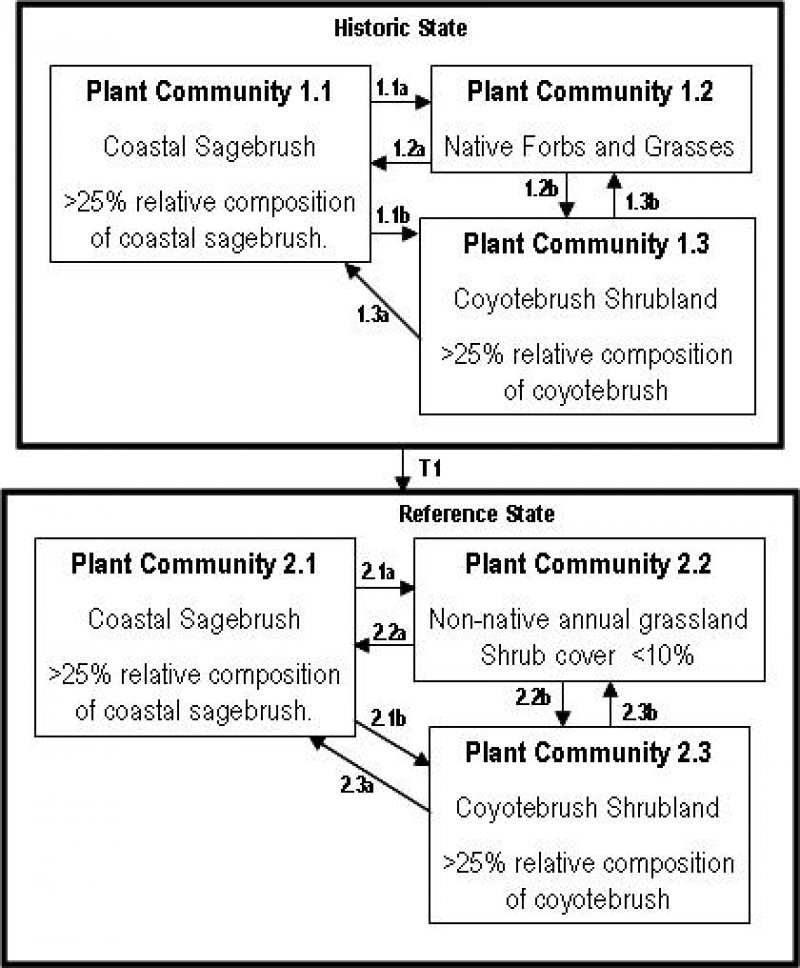

State and transition model

Figure 3. State Transition Model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 6 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State - Plant Community 2.1

Community 1.1

Reference State - Plant Community 2.1

Figure 4. coastal sage

Figure 5. coastal sage

This state is similar to the historic state, and is still dominated by coastal sagebrush with a relative cover between 30 and 80 percent; however it is now intermixed with open, dense patches of non-native annual grasses and forbs, such as fennel (Foeniculum). Other species that can still be found in this plant community include coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis), lemonade sumac (Rhus integrifolia), island deerweed, redflower buckwheat (Eriogonum grande var. grande), and lupine (Lupinus) species. Community Pathway 2.1a: This transition from PC 2.1 to PC 2.2 occurs under a more frequent fire regime, due to the presence of non-native annual grasses. This type of fire frequency will keep the sagebrush from becoming very dominant in the overstory, leaving large, open dense areas of annual grasses and forbs. Community Pathway 2.1b: This transition from PC 2.1 to PC 2.3 can occur when a fire takes place in the sagebrush community, but does not burn hot enough to take the community to PC 2.2, but has burned hot enough to remove many of the sagebrush plants, giving dominance back to the coyotebrush.

Figure 6. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

State 2

Plant Community 1.2

Community 2.1

Plant Community 1.2

This is a somewhat short-lived state that is dominated by native bunchgrasses and forbs that are released after the fire has removed the sagebrush from the canopy. This plant community will remain dominant for approximately 2 to 5 years, depending on the severity of the burn, before the sagebrush begins to re-establish its dominance. Community Pathway 1.2a: This transition from PC 1.2 to PC 1.1 occurs as the flush of native grasses and forbs is shaded out by the sagebrush as it re-establishes and returns to it’s original pre-fire cover. Community Pathway 1.2b: This transition from PC 1.2 to PC 1.3 occurs when there is a coyotebrush seed source available post-fire and the fire has removed the sagebrush seed source. Note: No Data was collected on this state.

State 3

Plant Community 1.3

Community 3.1

Plant Community 1.3

Figure 7. Coyote Brush Scrubland

This state is dominated by coyotebrush that has established in place of the coastal sagebrush, post-fire. This can occur when the fire severity is such that much of the sagebrush has been removed completely from the site. Coyotebrush is more tolerant of fire and may act as a transition species for the sagebrush by creating more conducive conditions for sagebrush germination. Community Pathway 1.3a: This transition from PC 1.3 to PC 1.1 occurs as the coastal (California) sagebrush becomes tall enough to shade out the coyotebrush, regaining it’s dominance and killing off coyotebrush which is not very shade tolerant and cannot compete with sagebrush once it is an established plant. Community Pathway 1.3b: This transition from PC 1.3 to PC 1.2 occurs when a fire takes place before the sagebrush has time to establish itself within the coyotebrush shrubland. State Transition 1: Frequent fires, livestock grazing, and/or the invasion of non-native species will cause the Historic State to shift to the Reference State. As the fire frequency interval shortens to 5 to 10 years, the coastal sagebrush will be unable to regenerate and non-native grasses will start to dominate. The exotic grasses will create a fuel layer which can increase the severity of fires within the existing sagebrush patches. Note: No data was collected for this plant community.

State 4

Plant Community 2.2

Community 4.1

Plant Community 2.2

Figure 8. Non-Native Annual Grassland

This plant community occurs after fire has removed coastal sagebrush (Artemisia californica) and released the non-native annual grasses by opening up the canopy for germination. Fires can occur more often in this plant community, making this a much more long-lived plant community than the historic native bunchgrass community in the reference state. The primary species are slender oat (Avena barbata), wild oat (Avena fatua), ripgut brome (Bromus diandrus), soft brome (Bromus hordeaceus), and Spanish brome (Bromus madritensis). The annual production for the non-native annual grasses is precipitation-dependent, and highly variable. Site-specific factors, such as aspect, soil moisture, marine influences, and landscape position, also influence annual production of these grasses. Community Pathway 2.2a: This transition from PC 2.2 to PC 2.1 occurs as the flush of non-native annual grasses and forbs are shaded out by the sagebrush as it re-establishes and returns to its original pre-fire cover. Community Pathway 2.2b: This transition from PC 2.2 to PC 2.3 occurs when there is a coyotebrush seed source available post-fire and the fire has removed the sagebrush seed source.

Figure 9. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

State 5

Plant Community 2.3

Community 5.1

Plant Community 2.3

This state is similar to the coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis)-dominated plant community in the reference state, with the replacement of native bunchgrasses and forbs with non-native annual grasses and forbs. Coyotebrush is more successful at re-establishing in annual grassland habitats, and can thus act as a transition community for the coastal sagebrush which does not compete well with non-native annuals once they have fully established. Thus, once the coyotebrush has become well-established, it shades out and kills the annuals in the understory, opening safe sites for sagebrush seedlings to germinate and establish. Community Pathway 2.3a: This transition from PC 2.3 to PC 2.1 occurs as the coastal sagebrush becomes tall enough to shade out the coyotebrush, regaining it’s dominance and killing off coyotebrush which is not very shade tolerant and cannot compete with sagebrush once it is an established plant. Community Pathway 2.3b: This transition from PC 2.3 to PC 2.2 occurs when a fire takes place before the sagebrush has time to establish itself within the coyotebrush shrubland. Note: No data was collected for this plant community.

State 6

Historic State- Plant Community 1.1

Community 6.1

Historic State- Plant Community 1.1

This is the historic state and is dominated by coastal sagebrush (Artemisia californica) with a relative cover between 30 and 80 percent. Historically, this plant community would have been intermixed with open patches of native bunchgrasses and forbs. Other species that can be found in this reference community include coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis), lemonade sumac (Rhus integrifolia), island deerweed, redflower buckwheat (Eriogonum grande var. grande), and lupine (Lupinus) species. Community Pathway 1.1a: This transition from PC 1.1 to PC 1.2 occurs under the natural fire regime of approximately 25 to 30 years. This type of fire frequency would have kept the sagebrush cover from becoming a closed canopy, leaving open patches of bunchgrasses and forbs. Community Pathway 1.1b: This transition from PC 1.1 to PC 1.3 can occur when a fire takes place in the sagebrush community, but does not burn hot enough to take the community to PC 1.2, but has burned hot enough to remove many of the sagebrush plants, giving dominance back to the coyotebrush. Note: No data was collected in this plant community.

Additional community tables

Table 5. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 1 | shrubs | 175–3000 | ||||

| coastal sagebrush | ARCA11 | Artemisia californica | 100–2000 | – | ||

| redflower buckwheat | ERGRG5 | Eriogonum grande var. grande | 50–900 | – | ||

| Santa Cruz Island buckwheat | ERAR6 | Eriogonum arborescens | 0–540 | – | ||

| coyotebrush | BAPI | Baccharis pilularis | 25–100 | – | ||

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 2 | grasses | 50–2500 | ||||

| ripgut brome | BRDI3 | Bromus diandrus | 10–1800 | – | ||

| wild oat | AVFA | Avena fatua | 10–800 | – | ||

| purple needlegrass | NAPU4 | Nassella pulchra | 0–200 | – | ||

| perennial ryegrass | LOPEP | Lolium perenne ssp. perenne | 0–200 | – | ||

| soft brome | BRHO2 | Bromus hordeaceus | 0–100 | – | ||

| slender oat | AVBA | Avena barbata | 0–100 | – | ||

| foothill needlegrass | NALE2 | Nassella lepida | 0–90 | – | ||

| compact brome | BRMA3 | Bromus madritensis | 0–10 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | forbs | 1–450 | ||||

| lupine | LUPIN | Lupinus | 0–400 | – | ||

| common catchfly | SIGA | Silene gallica | 0–50 | – | ||

| bluedicks | DICA14 | Dichelostemma capitatum | 0–1 | – | ||

Table 6. Community 4.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | non-native grasses | 1000–3500 | ||||

| slender oat | AVBA | Avena barbata | 900–2600 | – | ||

| ripgut brome | BRDI3 | Bromus diandrus | 80–400 | – | ||

| common barley | HOVU | Hordeum vulgare | 10–210 | – | ||

| Darnel ryegrass | LOTE2 | Lolium temulentum | 5–100 | – | ||

| soft brome | BRHO2 | Bromus hordeaceus | 10–50 | – | ||

| compact brome | BRMA3 | Bromus madritensis | 1–50 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 2 | native forbs | 1–75 | ||||

| fiddleneck | AMSIN | Amsinckia | 0–50 | – | ||

| thistle | CIRSI | Cirsium | 0–50 | – | ||

| cryptantha | CRYPT | Cryptantha | 0–5 | – | ||

| island bristleweed | HADE4 | Hazardia detonsa | 0–5 | – | ||

| Wright's cudweed | PSCAM | Pseudognaphalium canescens ssp. microcephalum | 0–5 | – | ||

| 3 | non native forbs | 5–100 | ||||

| smooth cat's ear | HYGL2 | Hypochaeris glabra | 1–50 | – | ||

| burclover | MEPO3 | Medicago polymorpha | 1–15 | – | ||

| stork's bill | ERODI | Erodium | 1–10 | – | ||

| shortpod mustard | HIIN3 | Hirschfeldia incana | 1–10 | – | ||

| common sowthistle | SOOL | Sonchus oleraceus | 0–5 | – | ||

| lettuce | LACTU | Lactuca | 1–5 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 4 | shrubs | 2–50 | ||||

| coyotebrush | BAPI | Baccharis pilularis | 2–50 | – | ||

| Australian saltbush | ATSE | Atriplex semibaccata | 0–5 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

The endemic Island Grey Fox (Urocyon littoralis)is a species that utilizes the coastal sagebrush (Artemisia californica), as well as other habitats. The sagebrush provides critical cover for the fox from many predators, including the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). The foxes eat a variety of foods, including mice, large insects, and fruit.

Several species of birds and rodents, as well as the Channel Island deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) and the spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis) also use this area for food, cover, and nesting.

Feral pigs also still roam Santa Cruz Island, causing ground disturbance similar to a roto-tiller, eating tubers, acorns, other vegetation, and insects along the way. There is a pig eradication project that has been established by the NPS.

Hydrological functions

All but one of the soil map units associated with this ecological site, have high to very high runoff potential. When this site is showing signs of distress, there will be noticable erosion and sediment loss, as well as possible pedastelling and gully formations.

Recreational uses

Hiking trails are suitable in this area, as long as the slopes are not too steep, and erosion potential is taken into account.

Wood products

The Chumash Indians used the branches of the California sagebrush (Artemisia californica) for firesticks and arrow foreshafts. A poultice was made from the sagebrush for headaches, and was also used for some ceremonial occasions (Howard,1993).

Other products

N/A

Supporting information

Inventory data references

The following NRCS plots were used to describe this ecological site.

SC-105

SC-110

SC-303

SC-304

SC-305

SCV-105

SCV-378

SR-117- Site location

SRV-2

Type locality

| Location 1: Santa Barbara County, CA | |

|---|---|

| UTM zone | N |

| UTM northing | 3766353 |

| UTM easting | 766830 |

| General legal description | The site location is on Santa Rosa Island in the Canada Verde drainage. |

Other references

Allen E.B.; Eliason, S.A.; Marquez V.J.; Shultz, G.P.; Storms, N.K.; Stylinski, C.D.; Zink, T.A.; and Allen, M.F. What are the Limits to Restoration of Coastal Sage Scrub in Southern California? 2nd Interface Between Ecology and Land Development in California. J.E. Keeley, M.B. Keeley and C.J. Fotheringham, eds. USGS Open-File Report 00-62, Sacramento, California. In press.

Bowler, P.A. 2000. Ecological restoration of coastal sage scrub and it's potential role in habitat conservation plans. Environmental Management, vol. 26, supplement 1: pgs S85-S96.

Eliason S.A. and Allen, E.B. (1997). Exotic Grass Competition in Suppressing Native Shrubland Re-establishment. Restoration Ecology, September 1997, vol. 5, no.3 pp. 245-255. Blackwell Publishing.

Howard, Janet L. 1993. Artemisia californica. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2005, April 7].

Junak, Steve; Ayers, Tina; Scott, Randy; Wilken, Dieter; and Young, David (1995). A Flora of Santa Cruz Island. Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, Santa Barbara, CA.

Keeler-Wolf, Todd (1995). Post-Fire Emergency Seeding and Conservation In Southern California Shrublands. Brushfires in California Wildlands: Ecology and Resource Management. Edited by J.E. Keeley and T. Scott. 1995. Internatitional Association of Wildland Fire, Fairfield, WA.

Keeley, Jon E (2003). Fire and Invasive Plants in California Ecosystems. Fire Management Today, Volume 63, No. 2

Keeley, Jon E. (2002). Native American Impacts on Fire Regimes of the Pacific Coast Ranges. US Government, Journal of Biogeography, 29, p. 303-320. Blackwell Science Ltd.

Keeley, J.E. (2001). Fire and invasive species in Mediterranean-climate ecosystems of California. Pages 81–94 in K.E.M. Galley and T.P. Wilson (eds.). Proceedings of the Invasive Species Workshop: the Role of Fire in the Control and Spread of Invasive Species. Fire Conference 2000: the First National Congress on Fire Ecology, Prevention, and Management. Miscellaneous Publication No. 11, Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL.

Keeley, Jon E. and Keeley Sterling C. (1984). Postfire recovery of California Coastal Sage Scrub. American Midland Naturalist, Vol. 111, Issue 1 (Jan. 1984) pp. 105-117

Lyndal L. Laughrin, Ph.D. UC Santa Cruz Island Reserve Director. University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106

Minnich, Richard A. and Scott, Thomas A. Wildland Fire and the Conservation of Coastal Sage Scrub. Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside.

Steinberg, Peter D. 2002. Baccharis pilularis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2005, March 3].

Contributors

MMM

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.