Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R019XI113CA

Loamy volcanic slopes 13-24" p.z.

Accessed: 01/22/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Artemisia californica |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Nassella pulchra |

Physiographic features

This ecological site is found on all aspects of hills and mountains. Slopes generally range from 15 to 75 percent, and elevations range from sea level to 2625 feet.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hill

(2) Mountain slope |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 0 – 800 m |

| Slope | 15 – 75% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

This ecological site is found only on Santa Cruz Island, and due to its size, temperature and precipitation ranges have been averaged together to capture the entire island's variance.

The average annual precipitation is 19 inches with a range between 13 to 24 inches, mostly in the form of rain in the winter months (November through April). The average annual air temperature is approximately 56 to 73 degrees Fahrenheit, and the frost-free (>32F) season is 320 to 365 days.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 365 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 610 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Influencing water features

This site is not influenced by wetland or riparian water features.

Soil features

The soils on this site formed from residuum weathered from volcanic breccia, andesite, or basalt. The soils are shallow to moderately deep, with loamy surface textures and some with clayey sub-surface textures. They are well-drained with an available water capacity between 0.7 to 4.1 inches. Mean Annual Soil Temperatures (MAST) range from 59 to 71 degrees F, which are classified as thermic.

This ecological site is found in the following Map units and soil components:

SSA Map symbol Component

CA688 100 Tongva

CA688 101 Tongva

CA688 150 Tongva

CA688 271 Tongva

CA688 103 Topdeck

CA688 270 Topdeck

CA688 271 Topdeck

CA688 272 Topdeck

CA688 290 Topdeck

CA688 780 Typic Argixerolls

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Gravelly |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Clayey |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Slow to moderate |

| Soil depth | 18 – 99 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 15 – 40% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 2 – 10% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

1.78 – 10.41 cm |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

5.1 – 7.8 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

5 – 30% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

5% |

Ecological dynamics

The reference state for this ecological site is the coastal sagebrush community. It is characterized by relatively dense cover of coastal sagebrush (Artemisia californica) with Santa Cruz Island buckwheat (Eriogonum arborescens) and other native shrubs, forbs, and perennial grasses. The historical community has been severely impacted and altered since Anglo-European settlement. Much of the area which historically was coastal sagebrush has been altered to the annual grassland state. Natural states within this community include a coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis)-dominated state, a native annual state, and a forb state. Several factors have promoted the transition to the annual grassland state, primarily the introduction of non-native Mediterranean species, severe over-grazing of livestock, and a change in the fire regime.

During the mid 1800s and the early 1900s the Channel Islands were heavily impacted by grazing from sheep, goats, cattle, horses, and pigs. Livestock may have been brought to Santa Rosa Island as early as 1805. The first cattle were brought to Santa Cruz Island in 1830 to support 100 exiled Mexican convicts. Ranching began in 1839 with the first private land owner, Andres Castillero. By 1853 the Santa Cruz Island Ranch had a good reputation for its well-bred, healthy Merino sheep. The sheep population steadily increased as they began to roam wild. Their population was estimated to be over 50,000 between 1870 and 1885, and up to 100,000 by 1890. In 1939, as a response to their detrimental effects to the island, 35,000 sheep were rounded up for sale to the mainland and efforts began to eliminate the sheep. An estimated 180,000 sheep were shot during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1987 The Nature Conservancy became the sole owner of the western 90 percent of Santa Cruz Island. They continued to eliminate the sheep, and also began removing cattle from the island. Pigs were reportedly introduced to the island in 1853, and by 1854 were roaming freely. The pigs are currently being eliminated section by section from Santa Cruz Island. (Junak et al., 1995) Many acres were cultivated for various crops, but primarily for hay production. In 1922, 800 acres of hay were cultivated at Christi Ranch, Scorpion Ranch, and near Prisoners Harbor (Junak et al., 1995).

A study of the pollen in soil cores taken from an estuary on Santa Rosa Island reveal dramatic changes since the 1800s (Cole and Liu, 1994). The pollen analysis shows an increase in grass pollen more than double any period recorded in the prior 5000 years. It was suggested this could be due to the introduction of non-native annual grasses. The decline of grass pollen coincides with the introduction of large numbers of grazing livestock in the 1840s. Charcoal fragments also increased at this time, possibly attributed to ranchers burning areas to clear brush or an increased fire potential from the annual grasses. The first stork’s bill (Erodium) pollen was dated to 1850, with a peak in 1894. The non-native stork’s bill thrives on disturbed bare soil. A peak in fungal spores between 1874 and 1894 coincides with the peak in soil erosion and the sheep population. (Cole and Liu, 1994)

The heavy grazing of the livestock on the sagebrush leaves and shoots eventually caused the death of many shrubs, due to a lack of leaf area to support photosynthesis. The livestock also ate the flowers and seeds, reducing the chance of reproduction. The lack of vegetative cover and the trampling of hooves caused severe erosion over most of the island. Much of the nutrient rich topsoil was lost and replaced with shallower soils and harsh subsurface soils. These combined factors reduced the area covered by sagebrush, and enabled the invasion of annual grasses. However, comparison photos from Santa Cruz Island during the years of grazing and the years since show recovery of sagebrush in many areas, particularly on canyon sideslopes (Lyndal L. Laughrin, Ph.D. personal photos).

The natural fire interval for coastal sagebrush on the mainland is about 25 to 30 years (Allen et al,; Keeley and Keeley 1984). Due to the nature of the storms in that area, lightning initiated fires tend to be less frequent on the islands than on the mainland. Some studies suggest that if fire frequency becomes less than 5 to 10 years, the sagebrush shrubs will not be able to regenerate and annual grasses will dominate (Minnich and Scott). The non-native grasses have created a continuous fuel layer that did not exist before, which can quickly ignite and spread. The mixture of annual grasses within the sagebrush community has also increased the flammability and severity of fires within the existing sagebrush patches. Fire frequency has increased due to the intentional setting of fires during the ranching years, and because of accidental fires. Fire may be more frequent than in the past, but fire suppression efforts may counterbalance the increased ignition rate.

The use of fire by Native Americans and its affect on the pattern of sagebrush and grassland communities is unclear (Keeley, 2002). The Chumash Indians lived on, and visited many of the Channel Islands. Records show habitation for more than 6000 years, with an estimate of about 2000 people living on Santa Cruz Island in 1542. It is believed that fire was used in the coastal mountains of California to clear shrublands in favor of grasslands (Keeley, 2002). It is likely this practice was used to some extent on the Channel Islands as well.

The coastal sagebrush community is somewhat adapted to fire. Many of the shrub species in this community have the ability to resprout after moderate fires. After fire, annuals and perennials dominate for a couple of years. Shrubs will resprout within the first year and produce prolific seeds the second year. Through re-sprouting and seeding, the shrubs will begin to re-establish in the area and should regain dominance by the third year.

A study was done concerning the suppression of sagebrush by annual grasses (Eliason and Allen, 1997). It stated that the coastal sagebrush had difficulty competing with the non-native grasses during germination and the first season of growth. The most limiting resource was most likely water. Annual grasses tend to utilize soil water earlier in the season, leaving the soil depleted for the sagebrush. By the second year the grasses had less affect on the sagebrush. The study notes that succession back to sagebrush may be inhibited by the grasses, but restoration by planting young plants or by the removal of the grasses then reseeding, may be successful. The main problem when restoring coastal sagebrush shrubland is the issue of how to regain the biodiversity in the area. (Allen et al.)

Coyotebrush is often the first shrub to re-establish in the non-native annual grasslands. It does best in full sun on bare soil, such as eroded areas or sand dunes. Coyotebrush can develop into large patches and persist for many years. It tends to shade out the annual grasses, creating a suitable habitat for sagebrush seedling development. The sagebrush can eventually dominate because the coyotebrush does not regenerate well under the canopy of sagebrush (Steinburg, 2002).

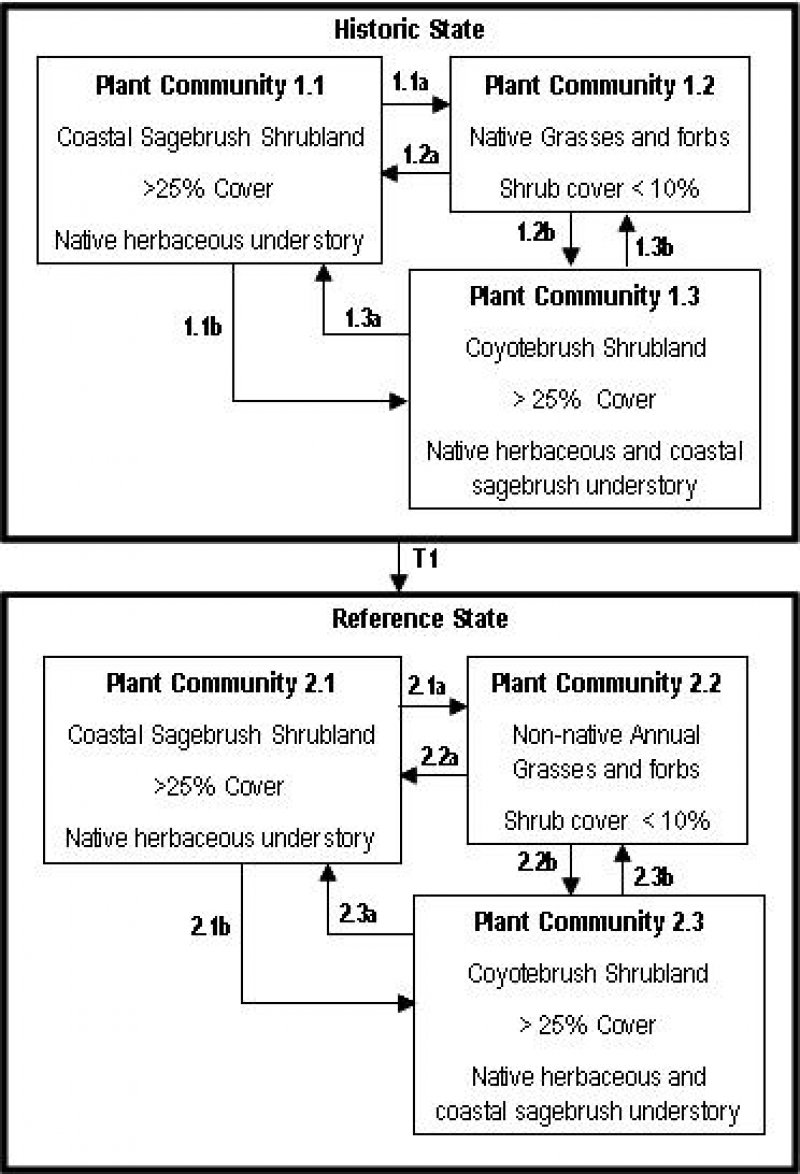

State and transition model

Figure 3. State Transition Model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 6 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State - Plant Community 2.1

Community 1.1

Reference State - Plant Community 2.1

This state is similar to PC 1.1, and is still dominated by coastal sagebrush with a relative cover of more than 25 percent; however it is now intermixed with open, dense patches of non-native annual grasses and forbs. The non-native grassland community is common throughout California. The primary species are slender oat (Avena barbata), wild oat (Avena fatua), ripgut grass (Bromus diandrus), soft brome (Bromus hordeaceus), and Spanish brome (Bromus madritensis). This state developed when the non-native grasses were introduced to the Channel Islands. The acreage covered by this state can be increased by heavy grazing and intentional burning to clear the shrubs. The production of non-native annual grasses is precipitation dependent, and highly variable. Site specific factors such as aspect, soil moisture, marine influences, and landscape position also influence annual production. Community Pathway 2.1a: This shift from PC 2.1 to PC 2.2 occurs under a more frequent fire regime, caused by the presence of non-native annual grasses. This type of fire frequency will keep the sagebrush from becoming very dominant in the overstory, leaving large, open areas of annual grasses and forbs. Community Pathway 2.1b: The shift from PC 2.1 to PC 2.3 occurs when there is a coyotebrush seed source available post-fire and the fire has removed the sagebrush seed source.

Figure 4. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

State 2

Plant Community 1.2

Community 2.1

Plant Community 1.2

This state is dominated by native bunchgrasses and forbs that are released after the fire has removed the sagebrush from the canopy. This plant community will remain dominant for approximately 2 to 5 years, depending on the severity of the burn, before the sagebrush begins to re-establish its dominance. Community Pathway 1.2a: The shift from PC 1.2 back to PC 1.1 occurs after an extended period of time without disturbance. Native forbs will germinate from seed while some sagebrush shrubs and perennial grasses will resprout from the surviving root stock. In the second year after fire, the sagebrush and native perennial grasses will produce prolific amounts of viable seeds. Coastal sagebrush will reclaim its dominance as the flush of native grasses and forbs are shaded out by the re-established sagebrush, eventually returning the site to its original pre-fire cover. (Keeley and Keeley, 1984; Allen et al.). Community Pathway 1.2b: The shift from PC 1.2 to PC 1.3 occurs when there is a coyotebrush seed source available post-fire and the fire has removed the sagebrush seed source.

State 3

Plant Community 2.3

Community 3.1

Plant Community 2.3

This community occurs when coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis) invades the disturbed area generally covered in non-native annual grasses. The mode of disturbance could be fire, heavy grazing, or cultivation, which removes the cover of coastal sagebrush. Coyotebrush slowly invades into the non-native grasslands and begins to shade them out as it forms thicker patches. Community Pathway 2.3a: The shift from PC 2.3 back to PC 2.1 will occur as coastal sagebrush establishes in the understory of the coyotebrush, and eventually becomes the dominant shrub again by increasing its canopy cover and inhibiting the growth of the young coyotebrush plants. Community Pathway 2.3b: This shift from PC 2.3 to PC 2.2 occurs when a fire takes place before the sagebrush has time to establish itself within the coyotebrush shrubland.

State 4

Plant Community 2.2

Community 4.1

Plant Community 2.2

This state is dominated by non-native grasses and forbs that are released after the fire has removed the sagebrush from the canopy. This plant community will remain for approximately 2 to 5 years before the sagebrush begins to re-establish its dominance, which will eventually lead back to PC 2.1. Community Pathway 2.2a: The shift from PC 2.2 back to PC 2.1 occurs after an extended period of time without disturbance. Non-native grasses and forbs will germinate from seed and some sagebrush shrubs will resprout from the surviving root stock. In the second year after fire the sagebrush will produce prolific amounts of viable seeds. Coastal sagebrush will reclaim its dominance as the flush of native grasses and forbs are shaded out by the re-established sagebrush, eventually returning the site to its original pre-fire cover. Community Pathway 2.2b: The shift from PC 2.2 to PC 2.3 occurs when there is a coyotebrush seed source available post-fire and the fire has removed the sagebrush seed source.

Figure 5. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

State 5

Historic State - Plant Community 1.1

Community 5.1

Historic State - Plant Community 1.1

The historic community is represented by a coastal sagebrush community, dominated by a dense cover of coastal sagebrush (Artemisia californica) and Santa Cruz Island buckwheat (Eriogonum arborescens). Other common native species include purple needlegrass (Nassella pulchra), redflower buckwheat (Eriogonum grande var. grande), coyotebrush (Bacharris pilularis), lemonade sumac (Rhus integrifolia), lupine species (lupinus sp.), and island broom (Lotus dendroideus). In the past, the cover of shrubs in the coastal sagebrush community may have been almost impenetrable. This ecological site differs from the loamy slopes ecosite (R020XI100CA) by having higher overall plant diversity and a greater dominance of Santa Cruz Island buckwheat (Eriogonum arborescens). Also, the coastal sagebrush ecological site is on soils derived from geologies other than volcanic origin. This ecological site is found on volcanic soils which encourage higher plant vigor and production. Community Pathway 1.1a: The shift from PC 1.1 to PC 1.2 occurs under the natural fire regime of approximately 25 to 30 years. This type of fire frequency would have kept the sagebrush cover from becoming a closed canopy, leaving open patches of bunchgrasses and forbs. Community Pathway 1.1b: The shift from PC 1.1 to PC 1.3 can occur when fire takes place in the sagebrush community, but does not burn hot enough to take the community to PC 1.2, but is hot enough to remove many of the sagebrush plants, giving dominance to the coyotebrush.

State 6

Plant Community 1.3

Community 6.1

Plant Community 1.3

This state is dominated by coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis) that has established in place of the coastal sagebrush after a fire. This can occur when the fire severity is such that much of the sagebrush has been removed completely from the site. Coyotebrush is more tolerant of fire and may act as a transition species for the sagebrush by creating more conducive conditions for sagebrush germination. Community Pathway 1.3a: The shift from PC 1.3 to PC 1.1 occurs over an extended period of time without disturbance as the coastal sagebrush becomes tall enough to shade out the coyotebrush, regaining its dominance and killing off coyotebrush which is not very shade tolerant and cannot compete with sagebrush once it is an established plant. Community Pathway 1.3b: This shift from PC 1.3 to PC 1.2 occurs when a fire takes place before the sagebrush has time to establish itself within the coyotebrush shrubland. Transition 1: Continued frequent fires and non-natural grazing by livestock and non-native wildlife can stress the historic state. This pressure can give an advantage to encroaching non-native plant species and may lead to the invasion of non-native annual grasslands.

Additional community tables

Table 5. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 1 | shrubs | 336–1681 | ||||

| coastal sagebrush | ARCA11 | Artemisia californica | 336–897 | – | ||

| Santa Cruz Island buckwheat | ERAR6 | Eriogonum arborescens | 336–897 | – | ||

| coyotebrush | BAPI | Baccharis pilularis | 1–56 | – | ||

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 2 | grasses | 112–897 | ||||

| wild oat | AVFA | Avena fatua | 11–897 | – | ||

| purple needlegrass | NAPU4 | Nassella pulchra | 0–224 | – | ||

| soft brome | BRHO2 | Bromus hordeaceus | 0–112 | – | ||

| compact brome | BRMA3 | Bromus madritensis | 0–112 | – | ||

| slender oat | AVBA | Avena barbata | 0–112 | – | ||

| foothill needlegrass | NALE2 | Nassella lepida | 0–101 | – | ||

| perennial ryegrass | LOPEP | Lolium perenne ssp. perenne | 0–56 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | forbs | 0–336 | ||||

| lupine | LUPIN | Lupinus | 0–448 | – | ||

| pricklypear | OPUNT | Opuntia | 0–56 | – | ||

| common catchfly | SIGA | Silene gallica | 0–56 | – | ||

| bluedicks | DICA14 | Dichelostemma capitatum | 0–1 | – | ||

Table 6. Community 4.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | non native grasses | 1121–3923 | ||||

| slender oat | AVBA | Avena barbata | 1009–2914 | – | ||

| ripgut brome | BRDI3 | Bromus diandrus | 90–448 | – | ||

| common barley | HOVU | Hordeum vulgare | 11–235 | – | ||

| Darnel ryegrass | LOTE2 | Lolium temulentum | 6–112 | – | ||

| soft brome | BRHO2 | Bromus hordeaceus | 11–56 | – | ||

| compact brome | BRMA3 | Bromus madritensis | 1–56 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 2 | native forbs | 1–84 | ||||

| fiddleneck | AMSIN | Amsinckia | 0–56 | – | ||

| thistle | CIRSI | Cirsium | 0–56 | – | ||

| cryptantha | CRYPT | Cryptantha | 0–6 | – | ||

| island bristleweed | HADE4 | Hazardia detonsa | 0–6 | – | ||

| Wright's cudweed | PSCAM | Pseudognaphalium canescens ssp. microcephalum | 0–6 | – | ||

| 3 | non native forbs | 6–112 | ||||

| smooth cat's ear | HYGL2 | Hypochaeris glabra | 1–56 | – | ||

| burclover | MEPO3 | Medicago polymorpha | 1–17 | – | ||

| stork's bill | ERODI | Erodium | 1–11 | – | ||

| shortpod mustard | HIIN3 | Hirschfeldia incana | 1–11 | – | ||

| common sowthistle | SOOL | Sonchus oleraceus | 0–6 | – | ||

| lettuce | LACTU | Lactuca | 1–6 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 4 | shrubs | 2–56 | ||||

| coyotebrush | BAPI | Baccharis pilularis | 2–56 | – | ||

| Australian saltbush | ATSE | Atriplex semibaccata | 0–6 | – | ||

Interpretations

Supporting information

Inventory data references

The following NRCS plots were used to describe this ecological site.

SC-393 lbs

SCV-7 lbs - Site location

Type locality

| Location 1: Santa Barbara County, CA | |

|---|---|

| UTM zone | N |

| UTM northing | 3768379 |

| UTM easting | 241362 |

| General legal description | The type location is on Santa Cruz Island, off the Lagunitas Secas Road. |

Other references

Allen E.B.; Eliason, S.A.; Marquez V.J.; Shultz, G.P.; Storms, N.K.; Stylinski, C.D.; Zink, T.A.; and Allen, M.F. What are the Limits to Restoration of Coastal Sage Scrub in Southern California? 2nd Interface Between Ecology and Land Development in California. J.E. Keeley, M.B. Keeley and C.J. Fotheringham, eds. USGS Open-File Report 00-62, Sacramento, California. In press.

Eliason S.A. and Allen, E.B. (1997). Exotic Grass Competition in Suppressing Native Shrubland Re-establishment. Restoration Ecology, September 1997, vol. 5, no.3 pp. 245-255. Blackwell Publishing.

Howard, Janet L. 1993. Artemisia californica. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2005, April 7].

Junak, Steve; Ayers, Tina; Scott, Randy; Wilken, Dieter; and Young, David (1995). A Flora of Santa Cruz Island. Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, Santa Barbara, CA.

Keeler-Wolf, Todd (1995). Post-Fire Emergency Seeding and Conservation In Southern California Shrublands. Brushfires in California Wildlands: Ecology and Resource Management. Edited by J.E. Keeley and T. Scott. 1995. Internatitional Association of Wildland Fire, Fairfield, WA.

Keeley, Jon E (2003). Fire and Invasive Plants in California Ecosystems. Fire Management Today, Volume 63, No. 2

Keeley, Jon E. (2002). Native American Impacts on Fire Regimes of the Pacific Coast Ranges. US Government, Journal of Biogeography, 29, p. 303-320. Blackwell Science Ltd.

Keeley, J.E. (2001). Fire and invasive species in Mediterranean-climate ecosystems of California. Pages 81–94 in K.E.M. Galley and T.P. Wilson (eds.). Proceedings of the Invasive Species Workshop: the Role of Fire in the Control and Spread of Invasive Species. Fire Conference 2000: the First National Congress on Fire Ecology, Prevention, and Management. Miscellaneous Publication No. 11, Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL.

Keeley, Jon E. and Keeley Sterling C. (1984). Postfire recovery of California Coastal Sage Scrub. American Midland Naturalist, Vol. 111, Issue 1 (Jan. 1984) pp. 105-117

Lyndal L. Laughrin, Ph.D. UC Santa Cruz Island Reserve Director. University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106

Minnich, Richard A. and Scott, Thomas A. Wildland Fire and the Conservation of Coastal Sage Scrub. Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside.

Steinberg, Peter D. 2002. Baccharis pilularis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2005, March 3].

Contributors

Munnecke

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.