Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R028BY048NV

CALCAREOUS MOUNTAIN RIDGE

Accessed: 12/22/2024

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

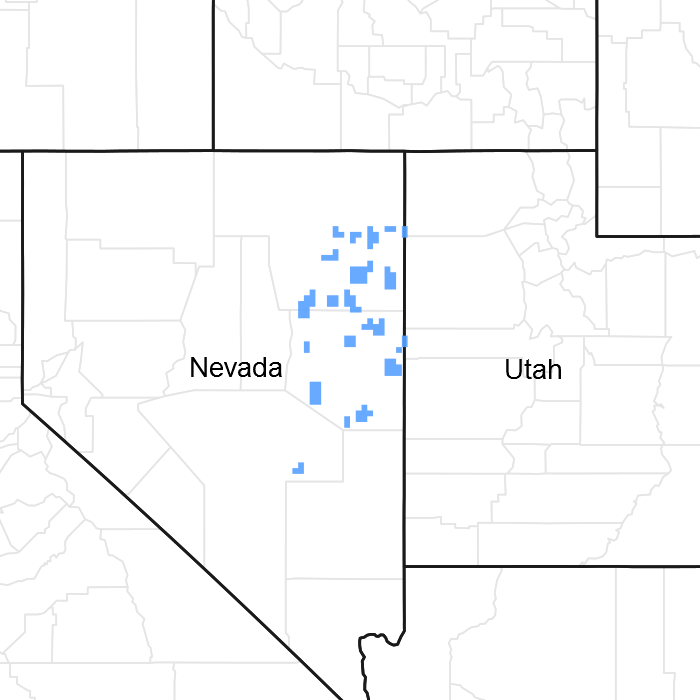

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 028B–Central Nevada Basin and Range

MLRA 28B occurs entirely in Nevada and comprises about 23,555 square miles (61,035 square kilometers). More than nine-tenths of this MLRA is federally owned. This area is in the Great Basin Section of the Basin and Range Province of the Intermontane Plateaus. It is an area of nearly level, aggraded desert basins and valleys between a series of mountain ranges trending north to south. The basins are bordered by long, gently sloping to strongly sloping alluvial fans. The mountains are uplifted fault blocks with steep sideslopes. Many of the valleys are closed basins containing sinks or playas. Elevation ranges from 4,900 to 6,550 feet (1,495 to 1,995 meters) in the valleys and basins and from 6,550 to 11,900 feet (1,995 to 3,630 meters) in the mountains.

The mountains in the southern half are dominated by andesite and basalt rocks that were formed in the Miocene and Oligocene. Paleozoic and older carbonate rocks are prominent in the mountains to the north. Scattered outcrops of older Tertiary intrusives and very young tuffaceous sediments are throughout this area. The valleys consist mostly of alluvial fill, but lake deposits are at the lowest elevations in the closed basins. The alluvial valley fill consists of cobbles, gravel, and coarse sand near the mountains in the apex of the alluvial fans. Sands, silts, and clays are on the distal ends of the fans.

The average annual precipitation ranges from 4 to 12 inches (100 to 305 millimeters) in most areas on the valley floors. Average annual precipitation in the mountains ranges from 8 to 36 inches (205 to 915 millimeters) depending on elevation. The driest period is from midsummer to midautumn. The average annual temperature is 34 to 52 degrees F (1 to 11 degrees C). The freeze-free period averages 125 days and ranges from 80 to 170 days, decreasing in length with elevation.

The dominant soil orders in this MLRA are Aridisols, Entisols, and Mollisols. The soils in the area dominantly have a mesic soil temperature regime, an aridic or xeric soil moisture regime, and mixed or carbonatic mineralogy. They generally are well drained, loamy or loamyskeletal, and shallow to very deep.

Nevada’s climate is predominantly arid, with large daily ranges of temperature, infrequent severe storms and heavy snowfall in the higher mountains. Three basic geographical factors largely influence Nevada’s climate: continentality, latitude, and elevation. The strong continental effect is expressed in the form of both dryness and large temperature variations. Nevada lies on the eastern, lee side of the Sierra Nevada Range, a massive mountain barrier that markedly influences the climate of the State. The prevailing winds are from the west, and as the warm moist air from the Pacific Ocean ascend the western slopes of the Sierra Range, the air cools, condensation occurs and most of the moisture falls as precipitation. As the air descends the eastern slope, it is warmed by compression, and very little precipitation occurs. The effects of this mountain barrier are felt not only in the West but throughout the state, as a result the lowlands of Nevada are largely desert or steppes.

The temperature regime is also affected by the blocking of the inland-moving maritime air. Nevada sheltered from maritime winds, has a continental climate with well-developed seasons and the terrain responds quickly to changes in solar heating. Nevada lies within the midlatitude belt of prevailing westerly winds which occur most of the year. These winds bring frequent changes in weather during the late fall, winter and spring months, when most of the precipitation occurs.

To the south of the mid-latitude westerlies, lies a zone of high pressure in subtropical latitudes, with a center over the Pacific Ocean. In the summer, this high-pressure belt shifts northward over the latitudes of Nevada, blocking storms from the ocean. The resulting weather is mostly clear and dry during the summer and early fall, with occasional thundershowers. The eastern portion of the state receives noteworthy summer thunderstorms generated from monsoonal moisture pushed up from the Gulf of California, known as the North American monsoon. The monsoon system peaks in August and by October the monsoon high over the Western U.S. begins to weaken and the precipitation retreats southward towards the tropics (NOAA 2004).

Ecological site concept

This site occurs on high mountain ridges, shoulders, and upper backslopes. Slopes range from 8 to 50 percent, but slope gradients of 8 to 30 percent are most typical. Elevations are 7500 to 10,100 feet.

The soils associated with this site are shallow, well drained and formed in residuum and colluvium derived from limestone and dolomite. Soils are skeletal with >35% percent gravel and cobbles, by volume, distributed throughout the profile. The soil profile is characterized by a mollic epipedon, a calcic horizon, carbonate minerology and is effervescent throughout. These soils usually have high amounts of gravels, cobbles or stones on the surface.

The reference state is dominated by bluebunch wheatgrass and black sagebrush. Production ranges from 100 to 350 pounds per acre.

Occasionally this site has a component of low sagebrush in the plant community. These occurrences are limited to 10,000+ feet where the amount of precipitation is overriding the influence of calcium carbonate in the soil profile. Future field work will verify that this is in fact low sagebrush and not the gray phase of black sagebrush.

Important abiotic factors influencing the presence of this ecological site include the convex landform shape that results in dryer conditions than the elevation and precipitation zone would suggest and a soil profile high in calcium carbonate.

Associated sites

| R028BY070NV |

MOUNTAIN LOAM 16+ P.Z. |

|---|---|

| R028BY085NV |

CALCAREOUS LOAM 16+ P.Z. |

Similar sites

| R028BY027NV |

SHALLOW CALCAREOUS SLOPE 14+ P.Z. More productive site |

|---|---|

| R028BY034NV |

MOUNTAIN RIDGE 12-14 P.Z. PSSPS-ACTH7 codominant grasses; lower elevations |

| R028BY038NV |

MOUNTAIN RIDGE 14+ P.Z. ARAR8 dominant or codominant shrub; soils derived from volcanic parent material |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Artemisia nova |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Pseudoroegneria spicata |

Physiographic features

This site occurs convex mountain ridges, shoulders, and upper backslopes. Slopes range from 8 to 50 percent, but slope gradients of 8 to 30 percent are typical. Elevations are 6800 to 10,000 feet, but typically occurs above 7500 feet.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Mountain

(2) Ridge |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 2,286 – 3,048 m |

| Slope | 8 – 30% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate associated with this site is semiarid, characterized by cold, moist winters and warm, dry summers.

Average annual precipitation ranges from 14 to over 20 inches. Mean annual air temperature is about 40 to 43 degrees F. The average growing season is about 50 to 70 days. Weather stations with a long term data record are currently not available for this ecological site. Associated climate data will be updated when information becomes available.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 70 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 50 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 406 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 3. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 4. Annual average temperature pattern

Influencing water features

Influencing water features are not associated with this site.

Soil features

The soils associated with this site are shallow to bedrock, well drained and formed in residuum and colluvium derived from limestone and dolomite. Soils are skeletal with >35 percent gravel and cobbles, by volume, distributed throughout the profile. The soil profile is characterized by a mollic epipedon, a calcic horizon, carbonate minerology and is effervescence throughout. Available water holding capacity is very low and the soil surface is typically covered with about 50% gravel.

Soil series associated with this site include: Adobe and Halacan.

The representative soil series is Halacan, a Loamy-skeletal, carbonatic Lithic Cryrendolls. Diagnostic horizons include a mollic epipedon from the soil surface to 28cm, identifiable secondary carbonates from the soil surface to 43cm, and a lithic contact at 43cm to hard fractured limestone. Clay content in the particle size control section averages 10 to 18 percent. Rock fragments range from 50 to 80 percent, mainly channers. Reaction is moderately alkaline or strongly alkaline. Soils are slightly to violently effervescent. Soil are derived from limestone or dolomite.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

limestone

(2) Colluvium – dolomite |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Very gravelly loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate to moderately rapid |

| Soil depth | 25 – 51 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 40 – 50% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

2.54 – 4.06 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

40 – 60% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

8 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

50 – 80% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0% |

Ecological dynamics

An ecological site is the product of all the environmental factors responsible for its development and it has a set of key characteristics that influence a site’s resilience to disturbance and resistance to invasives. Key characteristics include 1) climate (precipitation, temperature), 2) topography (aspect, slope, elevation, and landform), 3) hydrology (infiltration, runoff), 4) soils (depth, texture, structure, organic matter), 5) plant communities (functional groups, productivity), and 6) natural disturbance regime (fire, herbivory, etc.) (Caudle 2013). Biotic factors that influence resilience include site productivity, species composition and structure, and population regulation and regeneration (Chambers et al. 2013).

This ecological site is dominated by deep-rooted cool season, perennial bunchgrasses and long-lived shrubs (50+ years) with high root to shoot ratios. The dominant shrubs have a flexible generalized root system with development of both deep taproots and laterals near the surface (Comstock and Ehleringer 1992). In the Great Basin, the majority of annual precipitation is received during the winter and early spring. This continental semiarid climate regime favors growth and development of deep-rooted shrubs and herbaceous cool season plants using the C3 photosynthetic pathway (Comstock and Ehleringer 1992). Winter precipitation and slow melting of snow results in deeper percolation of moisture into the soil profile. Herbaceous plants, that are more shallow-rooted than shrubs, grow earlier in the growing season and thrive on spring rains, while the deeper rooted shrubs lag in phenological development because they draw from deeply infiltrating moisture from snowmelt the previous winter.

Periodic drought regularly influences sagebrush ecosystems and drought duration and severity has increased throughout the 20th century in much of the Intermountain West. Major shifts away from historical precipitation patterns have the greatest potential to alter ecosystem function and productivity. Species composition and productivity can be altered by the timing of precipitation and water availability within the soil profile (Bates et al. 2006).

Native insect outbreaks are also important drivers of ecosystem dynamics in sagebrush communities. Climate is generally believed to influence the timing of insect outbreaks especially a sagebrush defoliator, Aroga moth (Aroga websteri). Aroga moth infestations have occurred in the Great Basin in the 1960s, early 1970s, and is ongoing in Nevada since 2004 (Bentz et al. 2008). Thousands of acres of sagebrush have been impacted, with partial to complete die-off observed (Gates 1964, Hall 1965), but the research is inconclusive of the damage sustained by black sagebrush populations.

Black sagebrush is generally long-lived; therefore it is not necessary for new individuals to recruit every year for perpetuation of the stand. Infrequent large recruitment events and simultaneous low, continuous recruitment is the foundation of population maintenance (Noy-Meir 1973). Survival of the seedlings is dependent on adequate moisture conditions.

The perennial bunchgrasses that are co-dominant with the shrubs include bluebunch wheatgrass and muttongrass. Pine needlegrass, Indian ricegrass and squirreltail are other important grass species. These species generally have somewhat shallower root systems than the shrubs, but root densities are often as high or higher than those of shrubs in the upper 0.5 m of the soil profile. General differences in root depth distributions between grasses and shrubs results in resource partitioning in these shrub/grass systems.

The Great Basin sagebrush communities have high spatial and temporal variability in precipitation both among years and within growing seasons. Nutrient availability is typically low but increases with elevation and closely follows moisture availability. The invasibility of plant communities is often linked to resource availability. Disturbance can decrease resource uptake due to damage or mortality of the native species and depressed competition or can increase resource pools by the decomposition of dead plant material following disturbance. The invasion of sagebrush communities by cheatgrass has been linked to disturbances (fire, abusive grazing) that have resulted in fluctuations in resources (Chambers et al. 2007).

This ecological site has moderate to high resilience to disturbance and resistance to invasion. Increased resilience increases with elevation, aspect, increased precipitation and increased nutrient availability. Three possible alternative stable states have been identified for this site.

Fire Ecology:

Fire is not a major disturbance of these community types (Winward 2001), and would be infrequent. Historic fire return intervals have been estimated at 100 to 200 years (Kitchen and McArthur 2007); however, fires were probably patchy and very infrequent due to the low productivity of these sites. Black sagebrush plants have no morphological adaptations for surviving fire and must reestablish from seed following fire (Wright et al. 1979). The ability of black sagebrush to establish after fire is mostly dependent on the amount of seed deposited in the seed bank the year before the fire. Seeds typically do not persist in the soil for more than one growing season (Beetle 1960). A few seeds may remain viable in soil for two years (Meyer 2008); however, even in dry storage, black sagebrush seed viability has been found to drop rapidly over time, from 81% to 1% viability after 2 and 10 years of storage, respectively (Stevens et al. 1981). Thus, repeated frequent fires can eliminate black sagebrush from a site, however black sagebrush in zones receiving 12 to 16 inches of annual precipitation have been found to have greater fire survival (Boltz 1994). The effect of fire on bunchgrasses relates to culm density, culm-leaf morphology, and the size of the plant. The initial condition of bunchgrasses within the site along with seasonality and intensity of the fire all factor into the individual species response. For most forbs and grasses the growing points are located at or below the soil surface providing relative protection from disturbances which decrease above ground biomass, such as grazing or fire. Thus, fire mortality is more correlated to duration and intensity of heat which is related to culm density, culm-leaf morphology, size of plant and abundance of old growth (Wright 1971, Young 1983). Fire will remove aboveground biomass from bluebunch wheatgrass but plant mortality is generally low (Robberecht and Defossé 1995). However, season and severity of the fire will influence plant response. Plant response will vary depending on post-fire soil moisture availability.

Fire will remove aboveground biomass from bluebunch wheatgrass but plant mortality is generally low (Robberecht and Defossé 1995) because the buds are underground (Conrad and Poulton 1966) or protected by foliage. Uresk et al. (1976) reported burning increased vegetative and reproductive vigor of bluebunch wheatgrass. Thus, bluebunch wheatgrass is considered to experience slight damage to fire but is more susceptible in drought years (Young 1983). Plant response will vary depending on season, fire severity, fire intensity and post-fire soil moisture availability.

Muttongrass is top killed by fire but will resprout after low to moderate severity fires. A study by Vose and White (1991) in an open sawtimber site, found minimal difference in overall effect of burning on mutton grass.

Indian ricegrass may be slightly to severely damaged by fire, depending on severity. It typically reestablishes from off-site seed (Young 1983). Thus the presence of surviving, seed producing plants is necessary for reestablishment of Indian ricegrass. Proper grazing management following fire to promote seed production and establishment of seedlings is critical.

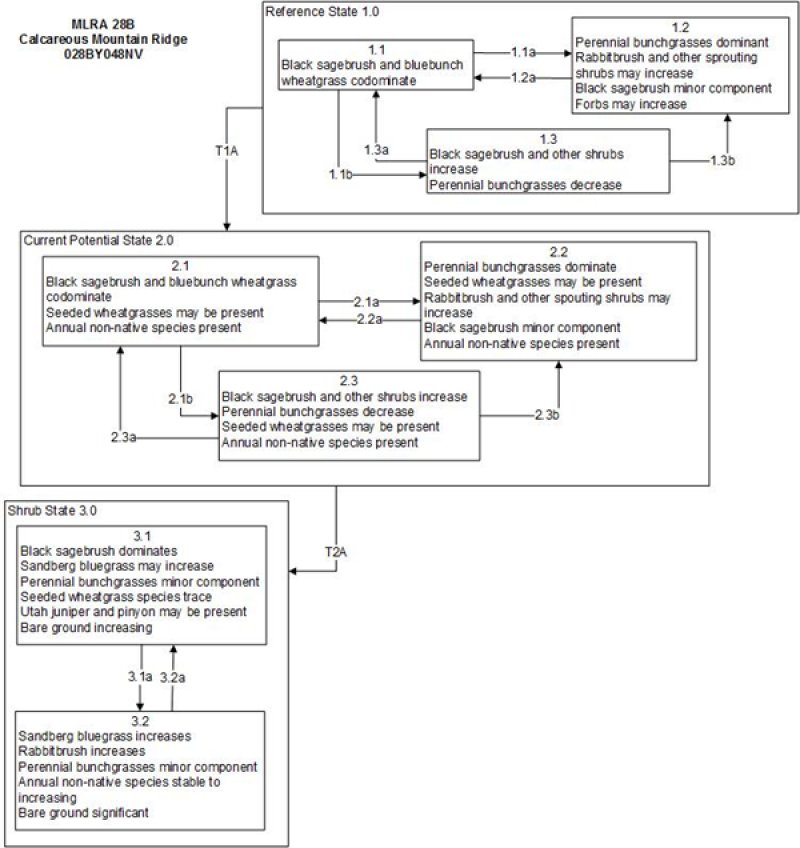

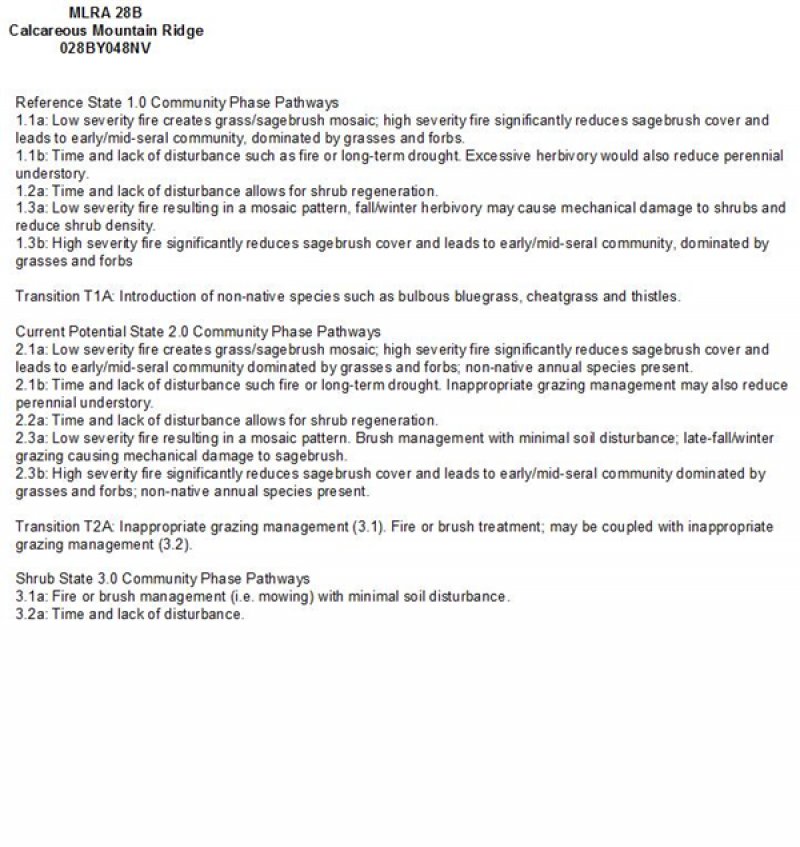

State and transition model

Figure 5. State and Transition Model

Figure 6. Legend

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State

The Reference State 1.0 is a representative of the natural range of variability under pristine conditions. The Reference State has three general community phases; a shrub-grass dominant phase, a perennial grass dominant phase and a shrub dominant phase. State dynamics are maintained by interactions between climatic patterns and disturbance regimes. Negative feedbacks enhance ecosystem resilience and contribute to the stability of the state. These include the presence of all structural and functional groups, low fine fuel loads, and retention of organic matter and nutrients. Plant community phase changes are primarily driven by fire, periodic drought and/or insect or disease attack.

Community 1.1

Community Phase

This community is dominated by black sagebrush, bluebunch wheatgrass, bluebunch wheatgrass, muttongrass and pine needlegrass. Forbs and other grasses make up smaller components. Potential vegetative composition is approximately 45% grasses, 10% forbs and 45% shrubs. Approximate ground cover (basal and canopy) is 15 to 25 percent.

Figure 7. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 50 | 101 | 177 |

| Shrub/Vine | 50 | 101 | 176 |

| Forb | 11 | 22 | 39 |

| Total | 111 | 224 | 392 |

Community 1.2

Community Phase

This community phase is characteristic of a post-disturbance, early-seral community. Bluebunch wheatgrass, Indian ricegrass, muttongrass and other perennial bunchgrasses dominate. Sprouting shrubs such as Douglas rabbitbrushmay increase. Depending on fire severity, patches of intact sagebrush may remain.

Community 1.3

Community Phase

Sagebrush increases in the absence of disturbance. Decadent sagebrush dominates the overstory and the deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses in the understory are reduced either from competition with shrubs and/or from herbivory. Scattered Utah juniper or singleleaf pinyon may be present on the site.

Pathway a

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Wildfire will decrease or eliminate the overstory of sagebrush and allow for the perennial bunchgrasses to dominate the site. Fires will typically be low severity resulting in a mosaic pattern due to low fuel loads. A fire following an unusually wet spring may be more severe and reduce sagebrush cover to trace amounts.

Pathway b

Community 1.1 to 1.3

Time and lack of disturbance such as fire allows for sagebrush to increase and become decadent. Chronic drought, herbivory, or combinations of these will cause a decline in perennial bunchgrasses and fine fuels leading to a reduced fire frequency and allowing black sagebrush to dominate the site.

Pathway a

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Time and lack of disturbance will allow sagebrush to increase.

Pathway a

Community 1.3 to 1.1

A low severity fire, herbivory or combinations will reduce the sagebrush overstory and create a sagebrush/grass mosaic.

Pathway b

Community 1.3 to 1.2

Fire will decrease or eliminate the overstory of sagebrush and allow for the perennial bunchgrasses to dominate the site. Fires will typically be high severity due to the dominance of sagebrush in this community phase, resulting in removal of the overstory shrub community.

State 2

Current Potential State

This state is similar to the Reference State 1.0 with three similar community phases. Ecological function has not changed, however the resiliency of the state has been reduced by the presence of invasive weeds. Non-natives may increase in abundance but will not become dominant within this State. These non-natives can be highly flammable and can promote fire where historically fire had been infrequent. Negative feedbacks enhance ecosystem resilience and contribute to the stability of the state. These feedbacks include the presence of all structural and functional groups, low fine fuel loads, and retention of organic matter and nutrients. Positive feedbacks decrease ecosystem resilience and stability of the state. These include the non-natives’ high seed output, persistent seed bank, rapid growth rate, ability to cross pollinate, and adaptations for seed dispersal.

Community 2.1

Community Phase

This community phase is similar to the Reference State Community Phase 1.1, with the presence of non-native species in trace amounts. Black sagebrush, bluebunch wheatgrass, muttongrass and pine needlegrass dominate the site. Forbs and other shrubs and grasses make up smaller components of this site.

Community 2.2

Community Phase

Figure 8. TStringham_8/2014

This community phase is characteristic of a post-disturbance, early seral community where annual non-native species are present. Sagebrush is present in trace amounts; perennial bunchgrasses dominate the site. Depending on fire severity or intensity of Aroga moth infestations, patches of intact sagebrush may remain. Rabbitbrush may be sprouting. Annual non-native species are stable or increasing within the community.

Community 2.3

Community Phase

Black sagebrush dominates the overstory and perennial bunchgrasses in the understory are reduced, either from competition with shrubs or from inappropriate grazing, or from both. Rabbitbrush may be a significant component. Sandberg bluegrass may increase and become co-dominant with deep rooted bunchgrasses. Annual non-natives species may be stable or increasing due to lack of competition with perennial bunchgrasses. This site is susceptible to further degradation from grazing, drought, and fire. This community is at risk of crossing a threshold to either State 3.0 (grazing or fire) or State 4.0 (fire).

Pathway a

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Fire reduces the shrub overstory and allows for perennial bunchgrasses to dominate the site. Fires are typically low severity resulting in a mosaic pattern due to low fuel loads. A fire following an unusually wet spring or a change in management favoring an increase in fine fuels may be more severe and reduce sagebrush cover to trace amounts. Annual non-native species are likely to increase after fire.

Pathway b

Community 2.1 to 2.3

Time and lack of disturbance allows for sagebrush to increase and become decadent. Chronic drought reduces fine fuels and leads to a reduced fire frequency, allowing black sagebrush to dominate the site. Inappropriate grazing management reduces the perennial bunchgrass understory; conversely Sandberg bluegrass may increase in the understory depending on grazing management.

Pathway a

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Time and lack of disturbance and/or grazing management that favors the establishment and growth of sagebrush allows the shrub component to recover. The establishment of black sagebrush can take many years.

Pathway a

Community 2.3 to 2.1

Grazing management that reduces shrubs will allow for the perennial bunchgrasses in the understory to increase. Heavy late-fall/winter grazing may cause mechanical damage to sagebrush thus promoting the perennial bunchgrass understory. Brush treatments with minimal soil disturbance will also decrease sagebrush and release the perennial understory. Annual non-native species are present and may increase in the community. A low severity fire would decrease the overstory of sagebrush and allow for the understory perennial grasses to increase. Due to low fuel loads in this State, fires will likely be small creating a mosaic pattern.

Pathway b

Community 2.3 to 2.2

Fire will decrease or eliminate the overstory of sagebrush and allow for the perennial bunchgrasses to dominate the site. Fires will typically be high intensity due to the dominance of sagebrush in this community phase resulting in removal of the overstory shrub community. Annual non-native species respond well to fire and may increase post-burn. Brush treatment would reduce black sagebrush overstory and allow for perennial bunchgrasses to increase.

State 3

Shrub State

This state has two community phases, one that is characterized by a decadent black sagebrush overstory and the other with a rabbitbrush overstory. The site has crossed a biotic threshold and site processes are being controlled by shrubs. Bare ground has increased and pedestalling of grasses may be excessive.

Community 3.1

Community Phase

Decadent black sagebrush dominates the overstory. Rabbitbrush may be a significant component. Deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses may be present in trace amounts or absent from the community. Annual non-native species increase. Bare ground is significant and soil redistribution may be occuring. This community phase may be at risk of transitioning to Annual State.

Community 3.2

Community Phase

Rabbitbrush dominates the overstory. Annual non-native species may be increasing and bare ground is significant. This site is at risk for an increase in invasive annual weeds.

Pathway a

Community 3.1 to 3.2

Fire reduces black sagebrush to trace amounts and allows for sprouting shrubs such as rabbitbrush to dominate. Shadscale may also establish post-fire and become dominate. Inappropriate or excessive sheep grazing could also reduce cover of sagebrush and allow for shadscale or sprouting shrubs to dominate the community. Brush treatments with minimal soil disturbance would facilitate sprouting shrubs and Sandberg bluegrass.

Pathway a

Community 3.2 to 3.1

Time and lack of disturbance and/or grazing management that favors the establishment and growth of sagebrush allows for the shrub component to recover. The establishment of black sagebrush may take many years.

Transition A

State 1 to 2

Trigger: This transition is caused by the introduction of non-native annual plants, such as cheatgrass and mustards. Slow variables: Over time the annual non-native species will increase within the community. Threshold: Any amount of introduced non-native species causes an immediate decrease in the resilience of the site. Annual non-native species cannot be easily removed from the system and have the potential to significantly alter disturbance regimes from their historic range of variation.

Transition A

State 2 to 3

Trigger: To Community Phase 3.1: Inappropriate cattle/horse grazing will decrease or eliminate deep rooted perennial bunchgrasses, increase Sandberg bluegrass and favor shrub growth and establishment. To Community Phase 3.2: Severe fire will remove sagebrush overstory, decrease perennial bunchgrasses and enhance Sandberg bluegrass. Soil disturbing brush treatments and/or inappropriate sheep grazing will reduce sagebrush and potentially increase sprouting shrubs and Sandberg bluegrass. Slow variables: Long term decrease in deep-rooted perennial grass density and/or black sagebrush. Threshold: Loss of deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses changes nutrient cycling, nutrient redistribution, and reduces soil organic matter. Loss of long-lived, black sagebrush changes the temporal and depending on the replacement shrub, the spatial distribution of nutrient cycling.

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Primary Perennial Grasses | 83–141 | ||||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSPS | Pseudoroegneria spicata ssp. spicata | 67–101 | – | ||

| muttongrass | POFE | Poa fendleriana | 11–22 | – | ||

| pine needlegrass | ACPI2 | Achnatherum pinetorum | 4–18 | – | ||

| 2 | Secondary Perennial Grasses | 11–22 | ||||

| Indian ricegrass | ACHY | Achnatherum hymenoides | 1–7 | – | ||

| squirreltail | ELEL5 | Elymus elymoides | 1–7 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | Perennial | 9–36 | ||||

| goldenweed | PYRRO | Pyrrocoma | 4–18 | – | ||

| aster | ASTER | Aster | 1–4 | – | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 1–4 | – | ||

| buckwheat | ERIOG | Eriogonum | 1–4 | – | ||

| gilia | GILIA | Gilia | 1–4 | – | ||

| lupine | LUPIN | Lupinus | 1–4 | – | ||

| phlox | PHLOX | Phlox | 1–4 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 4 | Primary Shrubs | 83–112 | ||||

| black sagebrush | ARNO4 | Artemisia nova | 78–101 | – | ||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 4–11 | – | ||

| 5 | Secondary Shrubs | 4–18 | ||||

| prairie sagewort | ARFR4 | Artemisia frigida | 2–4 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Livestock Interpretations:

This site is suitable for livestock grazing. Considerations for grazing management including timing, intensity and duration of grazing. Targeted grazing could be used to decrease the density of non-natives.

Bluebunch wheatgrass is considered one of the most important forage grass species on western rangelands for livestock. Bluebunch wheatgrass is moderately grazing tolerant and is very sensitive to defoliation during the active growth period (Blaisdell and Pechanec 1949, Laycock 1967, Anderson and Scherzinger 1975, Britton et al. 1990). Herbage and flower stalk production was reduced with clipping at all times during the growing season; however, clipping was most harmful during the boot stage (Blaisdell and Pechanec 1949)). Tiller production and growth of bluebunch was greatly reduced when clipping was coupled with drought (Busso and Richards 1995). Mueggler (1975) estimated that low vigor bluebunch wheatgrass may need up to 8 years rest to recover. Although an important forage species, it is not always the preferred species by livestock and wildlife.

Pine needlegrass provides a palatable and nutritious feed for livestock during the spring and early summer. In winter, at lower elevations, black sagebrush is heavily utilized by domestic sheep.

Douglas’ rabbitbrush is tolerant of grazing and may be “rejuvenated” by foliage removal. Douglas’ rabbitbrush commonly increases on degraded rangelands as more palatable species are removed.

Muttongrass is excellent forage for domestic livestock especially in the early spring. Muttongrass begins growth in late winter and early spring, which makes it available before many other forage plants. Muttongrass is known for fattening sheep. Muttongrass greens up in early spring before many of the other perennial bunchgrasses, and is highly palatable to all classes of livestock as well as good forage to wildlife such as deer and elk (Dayton 1937). In a study by Currie et al. (1977) in a ponderosa pine forest, deer preferred muttongrass which comprised up to 18% of their diet.

Indian ricegrass is highly palatable to all classes of livestock in both green and cured condition. It supplies a source of green feed before most other native grasses have produced much new growth. In winter, at lower elevations, black sagebrush is heavily utilized by domestic sheep.

Domestic livestock will utilize black sagebrush. The domestic sheep industry that emerged in the Great Basin in the early 1900s was largely based on wintering domestic sheep in black sagebrush communities (Mozingo 1987). Domestic sheep will browse black sagebrush during all seasons of the year depending on the availability of other forage species with greater amounts being consumed in fall and winter. In winter, at lower elevations, black sagebrush is heavily utilized by domestic sheep. Although the seeds are apparently not injurious, grazing animals avoid them when they begin to mature. Sheep, however, have been observed to graze the leaves closely, leaving stems untouched (Eckert and Spencer 1987). Black sagebrush is generally less palatable to cattle than to domestic sheep and wild ungulates (McArthur et al. 1982); however, cattle use of black sagebrush has also been shown to be greatest in fall and winter (Schultz and McAdoo 2002), with only trace amounts being consumed in summer (Van Vuren 1984).

Stocking rates vary over time depending upon season of use, climate variations, site, and previous and current management goals. A safe starting stocking rate is an estimated stocking rate that is fine-tuned by the client by adaptive management through the year and from year to year.

Wildlife Interpretations:

Black sagebrush are desirable forage plants and also act as good cover for livestock and wildlife (Blaisdell et al. 1982). In Nevada, black sagebrush supports bitterbrush communities used by mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) (Blaisdell et al. 1982). Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) do best where shrub cover is moderate to low, therefore, low sagebrush varieties may be preferred in some areas over big sagebrush varieties (Blaisdell et al. 1982). It is especially important on low elevation winter ranges in the southern Great Basin, where extended snow free periods allow animals access to plants throughout most of the winter. In these areas it is heavily utilized by pronghorn and mule deer. Furthermore, a review identified black sagebrush as the most important source of winter browse for pronghorn in Utah (Allen et al. 1984). Black sagebrush palatability has been rated as moderate to high depending on the ungulate and the season of use (Horton 1989, Wambolt 1996). The palatability of black sagebrush increase the potential negative impacts on remaining black sagebrush plants from grazing or browsing pressure following fire (Wambolt 1996). Pronghorn utilize black sagebrush heavily (Beale and Smith 1970). On the Desert Experiment Range, black sagebrush was found to comprise 68% of pronghorn diet even though it was only the third most common plant. Fawns were found to prefer black sagebrush utilizing it more than all other forage species combined (Beale and Smith 1970).

In a study by Behan and Welch (1985) black sagebrush accessions were preferred over six other big sagebrush accessions for winter habitat by mule deer. Black sagebrush (and other sagebrush communities) are less attractive to elk (Alces alces) and moose (Alces americanus). In southwestern Wyoming comparing winter habitat use by wild ungulates, elk and moose used Wyoming big sagebrush and black sagebrush community less than expected, while mule deer used it almost exclusively (Oedekoven et al. 1987).

Bird species use black sagebrush dominant habitat. Sage thrashers (Oreoscoptes montanus) and most passerines prefer areas with black sagebrush and other dwarf shrubs over areas with taller shrubs (Medin et al. 2000). Brewer's sparrow (Spizella breweri), sage sparrow (Amphispiza belli), and sage thrasher, also use black sagebrush communities for cover and feed (Paige and Ritter 1999). Greater Sage grouse (Centrocerus urophasianus) are known obligates in black sagebrush and other sagebrush habitats and will use black sagebrush sites as winter grounds (Connelly et al. 2000). For example: sage-grouse on the Snake River Plains of Idaho use black sagebrush-big sagebrush communities as winter range, and in Nevada, sage-grouse select wind-swept ridges with short, scattered black sagebrush plants as winter feeding areas (Clements and Young 1997). In fact, throughout the west, greater sage grouse use mixed sagebrush habitats of big sagebrush and black sagebrush stands.

Pygmy rabbits (Brachylagus idahoensis), a threatened species of conservation concern throughout California, Oregon, Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and Utah (endangered in Washington) often burrow where low sagebrush mixes with mountain big sagebrush. Black sagebrush, is often a component of low sagebrush communities and is an important shrub for pygmy rabbits and other sagebrush obligate species (Oregon Conservation Strategy, 2006).

Rodents also use black sagebrush habitats. A study in northeastern Nevada showed deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus), Great Basin pocket mice (Perognathus merriami), and Ord's kangaroo rats (Dipodomys ordii) used gray low sagebrush-black sagebrush communities on dry ridge tops in late spring and summer (McAdoo et al. 2006). Rodents on cold-desert warm-desert ecotones within the Nevada Test Site preferred cold-desert communities over transition and warm-desert communities in which black sagebrush communities were more abundant (Hansen et al. 1999). Black sagebrush communities also support predators. According to study by MacLaren et al. (1988) greater sage-grouse are the primary avian prey of golden eagles in a mixed big sagebrush-black sagebrush shrubland in southeastern Wyoming.

Several reptiles and amphibians are distributed throughout the sagebrush steppe in the west in Nevada, where basin big sagebrush is known to grow (Bernard and Brown 1977). Reptile species including: eastern racers (Coluber constrictor), ringneck snakes (Diadophis punctatus), night snakes (Hypsiglena torquata), Sonoran mountain kingsnakes (Lampropeltis pyromelana), striped whipsnakes (Masticophis taeniatus), gopher snakes (Pituophis catenifer), long-nosed snakes (Rhinocheilus lecontei), wandering gartersnakes (Thamnophis elegans vagrans), Great Basin rattlesnakes (Crotalus oreganus lutosus), Great Basin collared lizard (Crotaphytus bicinctores), long-nosed leopard lizard (Gambelia wislizenii), short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma douglassii), desert-horned lizard (Phrynosoma platyrhinos), sagebrush lizards (Sceloporus gracisosus), western fence lizards (Sceloporus occidentalis), northern side-blotched lizards (Uta uta stansburiana), western skinks (Plestiodon skiltonianus), and Great Basin whiptails (Aspidoscelis tigris tigris) occur in areas where sagebrush is dominant. Similarly, amphibians such as: western toads (Anaxyrus boreas), Woodhouse’s toads (Anaxyrus woodhousii), northern leopard frogs (Lithobates pipiens), Columbia spotted frogs (Rana luteiventris), bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus), and Great Basin spadefoots (Spea intermontana) also occur throughout the Great Basin in areas sagebrush species are dominant (Hamilton 2004). Studies have not determined if reptiles and amphibians prefer certain species of sagebrush; however, researchers agree that maintaining habitat where basin big sagebrush and reptiles and amphibians occur is important. In fact, wildlife biologists have noticed declines in reptiles where sagebrush steppe habitat has been seeded with introduced grasses (West 1999 and ref. therein).

Douglas’ rabbitbrush provides an important source of browse for wildlife, particularly in the late fall and early winter after more palatable species have been depleted. Wild ungulates show varying preference for Douglas’ rabbitbrush depending on season, locality, and subspecies. Mature or partially mature plants are generally preferred to green, immature ones. Douglas’ rabbitbrush provides important cover for pronghorn fawns. In parts of the Great Basin, plants regrew rapidly after they were nearly completely consumed by spring-browsing black-tailed jackrabbits.

Bluebunch wheatgrass is considered one of the most important forage grass species on western rangelands for wildlife. Bluebunch wheatgrass does not generally provide sufficient cover for ungulates, however, mule deer were frequently found in bluebunch-dominated grasslands.

Pine needlegrass provides a palatable and nutritious feed for wildlife during the spring and early summer.

Deer and elk make heavy use of muttongrass, especially in early spring when other green forage is scarce. Depending upon availability of other nutritious forage, deer may use muttongrass in all seasons. Muttongrass cures well and is an important fall and winter deer food in some areas.

Indian ricegrass is eaten by pronghorn in "moderate" amounts whenever available. A number of heteromyid rodents inhabiting desert rangelands show preference for seed of Indian ricegrass. Indian ricegrass is an important component of jackrabbit diets in spring and summer. Indian ricegrass seed provides food for many species of birds. Doves, for example, eat large amounts of shattered Indian ricegrass seed lying on the ground.

Bottlebrush squirreltail is a dietary component of domestic livestock and wildlife species. Bottlebrush squirreltail may provide forage for mule deer and pronghorn.

Hydrological functions

Runoff is very high. Permeability is moderate to moderately rapid. Rills are none to rare. Rock fragments armor the soil surface. Water flow patterns are none to rare. Pedestals are rare to few. Occurrence is usually limited to areas of water flow patterns. Frost heaving of shallow rooted plants should not be considered an indicator of soil erosion. Gullies are none. Perennial herbaceous plants (especially deep-rooted bunchgrasses) slow runoff and increase infiltration. Shrubs break raindrop impact and provide opportunity for snow catch and accumulation on site.

Recreational uses

Aesthetic value is derived from the diverse floral and faunal composition and the colorful flowering of wild flowers and shrubs during the spring and early summer. This site offers rewarding opportunities to photographers and for nature study. This site is used for hiking and has potential for upland and big game hunting.

Other products

Douglas’ rabbitbrush can be a source of rubber and possibly valuable resins.

Other information

Black sagebrush is an excellent species to establish on sites where management objectives include restoration or improvement of domestic sheep, pronghorn, or mule deer winter range.

Supporting information

Type locality

| Location 1: White Pine County, NV | |

|---|---|

| Township/Range/Section | T14N R63E S10 |

| Latitude | 39° 5′ 33″ |

| Longitude | 114° 52′ 58″ |

| General legal description | SW ¼ SW ¼, Approximately 1.7 miles northwest of Silver King Ward Mining District headquarters (old Ward Site), Egan Range, White Pine County, Nevada. This site also occurs in Elko County, Nevada. |

Other references

Akinsoji, A. 1988. Postfire vegetation dynamics in a sagebrush steppe in southeastern Idaho, USA. Vegetatio 78:151-155.

Anderson, E. W. and R. J. Scherzinger. 1975. Improving quality of winter forage for elk by cattle grazing. Journal of Range Management:120-125.

Barney, M. A. and N. C. Frischknecht. 1974. Vegetation Changes following Fire in the Pinyon-Juniper Type of West-Central Utah. Journal of Range Management 27:91-96.

Bates, J. D., T. Svejcar, R. F. Miller, and R. A. Angell. 2006. The effects of precipitation timing on sagebrush steppe vegetation. Journal of Arid Environments 64:670-697.

Beale, D. M. and A. D. Smith. 1970. Forage Use, Water Consumption, and Productivity of Pronghorn Antelope in Western Utah. The Journal of Wildlife Management 34:570-582.

Bentz, B., D. Alston, and T. Evans. 2008. Great Basin Insect Outbreaks. Pages 45-48 in Collaborative Management and Research in the Great Basin -- Examining the issues and developing a framework for action Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-204. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO.

Blaisdell, J. P. and J. F. Pechanec. 1949. Effects of Herbage Removal at Various Dates on Vigor of Bluebunch Wheatgrass and Arrowleaf Balsamroot. Ecology 30:298-305.

Bradley, A. F., N. V. Noste, and W. C. Fischer. 1992. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-287: Fire ecology of forests and woodlands in Utah. . U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Ogden, UT.

Britton, C. M., G. R. McPherson, and F. A. Sneva. 1990. Effects of burning and clipping on five bunchgrasses in eastern Oregon. Great Basin Naturalist 50:115-120.

Bunting, S. 1994. Effects of Fire on Juniper woodland ecosystems in the great basin.in Proceedings--Ecology and Management of Annual Rangelands. USDA: FS Intermountain Research Station.

Busso, C. A. and J. H. Richards. 1995. Drought and clipping effects on tiller demography andgrowth of two tussock grasses in Utah. Journal of Arid Environments 29:239-251.

Caudle, D., J. Dibenedetto , M. Karl , H. Sanchez , and C. Talbot. 2013. Interagency ecological site handbook for rangelands.

Chambers, J., B. Bradley, C. Brown, C. D’Antonio, M. Germino, J. Grace, S. Hardegree, R. Miller, and D. Pyke. 2013. Resilience to Stress and Disturbance, and Resistance to Bromus tectorum L. Invasion in Cold Desert Shrublands of Western North America. Ecosystems:1-16.

Chambers, J. C., B. A. Roundy, R. R. Blank, S. E. Meyer, and A. Whittaker. 2007. What makes great basin sagebrush ecosystems invasible by Bromus tectorum? Ecological Monographs 77:117-145.

Comstock, J. P. and J. R. Ehleringer. 1992. Plant adaptation in the Great Basin and Colorado plateau. Western North American Naturalist 52:195-215.

Conrad, C. E. and C. E. Poulton. 1966. Effect of a wildfire on Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass. Journal of Range Management:138-141.

Currie, P. O., D. W. Reichert, J. C. Malechek, and O. C. Wallmo. 1977. Forage Selection Comparisons for Mule Deer and Cattle under Managed Ponderosa Pine. Journal of Range Management 30:352-356.

Dayton, W. 1937. Range plant handbook. USDA, Forest Service. Bull.

Eckert, R. E., Jr. and J. S. Spencer. 1987. Growth and reproduction of grasses heavily grazed under rest-rotation management. Journal of Range Management 40:156-159.

Evans, R. A. and J. A. Young. 1978. Effectiveness of Rehabilitation Practices following Wildfire in a Degraded Big Sagebrush-Downy Brome Community. Journal of Range Management 31:185-188.

Everett, R. L. and K. Ward. 1984. Early plant succession on pinyon-juniper controlled burns. Northwest Science 58:57-68.

Fire Effects Information System (Online; http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/).

Ganskopp, D. 1988. Defoliation of Thurber Needlegrass: Herbage and Root Responses. Journal of Range Management 41:472-476.

Gates, D. H. 1964. Sagebrush infested by leaf defoliating moth. Journal of Range Management 17:209-210.

Hall, R. C. 1965. Sagebrush defoliator outbreak in Northern California. Res. Note PSW-RN-075., Berkeley, CA.

Horton, H. 1989. Interagency forage and conservation planting guide for Utah. Extension circular 433. Utah State University, Utah Cooperative Extension Service, Logan UT.

Houghton, J.G., C.M. Sakamoto, and R.O. Gifford. 1975. Nevada’s Weather and Climate, Special Publication 2. Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, Mackay School of Mines, University of Nevada, Reno, NV.

Kitchen, S. G. and E. D. McArthur. 2007. Big and black sagebrush landscapes. Fire Ecology and Management of the Major Ecosystems of Southern Utah. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-202, Fort Collins, CO. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. :73-94.

Koniak, S. 1985. Succession in pinyon-juniper woodlands following wildfire in the Great Basin. The Great Basin Naturalist 45:556-566.

Laycock, W. A. 1967. How heavy grazing and protection affect sagebrush-grass ranges. Journal of Range Management:206-213.

McArthur, E. D., A. Blaner, A. P. Plummer, and R. Stevens. 1982. Characteristics and hybridization of important Intermountain shrubs: 3. Sunflower family. En Ref. in Forest. Abstr 43:2176.

Miller, R. F., J. C. Chambers, D. A. Pyke, F. B. Pierson, and C. J. Williams. 2013. A review of fire effects on vegetation and soils in the Great Basin Region: response and ecological site characteristics.

Miller, R.F., R.J. Tausch, E.D. McArthur, D.D. Johnson, S.C. Sanderson 2008. Age structure and expansion of pinon-juniper woodlands: a regional perspective in the Intermountain West. Res.Pap.RMRS-RP-69. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 15 p.

Miller, R. F. and R. J. Tausch. 2000. The role of fire in pinyon and juniper woodlands: a descriptive analysis. Pages 15-30 in Proceedings of the invasive species workshop: the role of fire in the control and spread of invasive species. Fire conference.

Mozingo, H. N. 1987. Shrubs of the Great Basin: A natural history. Pages 67-72 in H. N. Mozingo, editor. Shrubs of the Great Basin. University of Nevada Press, Reno NV.

Mueggler, W. F. 1975. Rate and Pattern of Vigor Recovery in Idaho Fescue and Bluebunch Wheatgrass. Journal of Range Management 28:198-204.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2004. The North American Monsoon. Reports to the Nation. National Weather Service, Climate Prediction Center. Available online: http://www.weather.gov/

Norton, J.B., T.A. Monaco, J.M. Norton, D.A. Johnson, and T. A. Jones 2004. Soil morphology and organic matter dynamics under cheatgrass and sagebrush-steppe plant communities. Jo. of Arid Environments: 57, 445-466.

Noy-Meir, I. 1973. Desert Ecosystems: Environment and Producers. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4:25-51.

Richards, J. H. and M. M. Caldwell. 1987. Hydraulic lift: Substantial nocturnal water transport between soil layers by Artemisia tridentata roots. Oecologia 73:486-489.

Robberecht, R. and G. Defossé. 1995. The relative sensitivity of two bunchgrass species to fire. International Journal of Wildland Fire 5:127-134.

Schultz, B. W. and J. K. McAdoo. 2002. Common Sagebrush in Nevada. Special Publication SP-02-02. University of Nevada, Cooperative Extension, Reno, NV.

Smoliak, S., J. F. Dormaar, and A. Johnston. 1972. Long-Term Grazing Effects on Stipa-Bouteloua Prairie Soils. Journal of Range Management 25:246-250.

Stringham, T.K., P. Novak-Echenique, P. Blackburn, C. Coombs, D. Snyder and A. Wartgow. 2015. Final Report for USDA Ecological Site Description State-and-Transition Models, Major Land Resource Area 28A and 28B Nevada. University of Nevada Reno, Nevada Agricultural Experiment Station Research Report 2015-01. p. 1524.

Tausch, R. J. 1999. Historic pinyon and juniper woodland development. Proceedings: ecology and management of pinyon–juniper communities within the Interior West. Ogden, UT, USA: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, RMRS-P-9:12-19.

Tausch, R. J. and N. E. West. 1988. Differential establishment of pinyon and juniper following fire. American Midland Naturalist:174-184.

Tueller, P. T. and W. H. Blackburn. 1974. Condition and Trend of the Big Sagebrush/Needleandthread Habitat Type in Nevada. Journal of Range Management 27:36-40.

Uresk, D. W., J. F. Cline, and W. H. Rickard. 1976. Impact of wildfire on three perennial grasses in south-central Washington. Journal of Range Management 29:309-310.

USDA-NRCS Plants Database (Online; http://www.plants.usda.gov).

Van Vuren, D. 1984. Summer Diets of Bison and Cattle in Southern Utah. Journal of Range Management 37:260-261.

Vose, J. M. and A. S. White. 1991. Biomass response mechanisms of understory species the first year after prescribed burning in an Arizona ponderosa-pine community. Forest Ecology and Management 40:175-187.

Wambolt, C. L. 1996. Mule Deer and Elk Foraging Preference for 4 Sagebrush Taxa. Journal of Range Management 49:499-503.

Wright, H. A. 1971. Why Squirreltail Is More Tolerant to Burning than Needle-and-Thread. Journal of Range Management 24:277-284.

Wright, H. A. and J. O. Klemmedson. 1965. Effect of Fire on Bunchgrasses of the Sagebrush-Grass Region in Southern Idaho. Ecology 46:680-688.

Young, R. P. 1983. Fire as a vegetation management tool in rangelands of the intermountain region. Pages 18-31 in Managing intermountain rangelands - improvement of range and wildlife habitats. USDA, Forest Service.

Contributors

MD/RK/HA

T. Stringham/P.Novak-Echenique

E. Hourihan

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Patti Novak-Echenique |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | State Rangeland Management Specialist |

| Date | 11/18/2009 |

| Approved by | PNovak-Echenique |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

Rills are none to rare. Rock fragments armor the soil surface. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Water flow patterns are none to rare. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

Pedestals are rare to few. Occurrence is usually limited to areas of water flow patterns. Frost heaving of shallow rooted plants should not be considered an indicator of soil erosion. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Bare Ground ± 5-15%. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

Gullies are none. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Fine litter (foliage from grasses and annual & perennial forbs) expected to move distance of slope length during intense summer convection storms or rapid snowmelt events. Persistent litter (large woody material) will remain in place except during catastrophic events. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil stability values should be 3 to 4 on most soil textures found on this site. Areas of this site occurring on soils that have a physical crust will probably have stability values less than 3. (To be field tested.) -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

Surface structure is thick platy or subangular blocky. Soil surface colors are dark and soils are typified by a mollic epipedon. Organic carbon of the surface 2 to 3 inches is typically 1 to 2 percent dropping off quickly below. Organic matter content can be more or less depending on micro-topography. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

Perennial herbaceous plants (especially deep-rooted bunchgrasses) slow runoff and increase infiltration. Shrubs break raindrop impact and provide opportunity for snow catch and accumulation on site. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

Compacted layers are not typical. Subangular blocky sub-surface horizons are not to be interpreted as compacted layers. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Reference State: Low shrubs (black sagebrush) = deep-rooted, cool season, perennial bunchgrassesSub-dominant:

Shallow-rooted, cool season, perennial grasses > associated shrubs > deep-rooted, cool season, perennial forbs = fibrous, shallow-rooted, cool season, perennial forbs = annual forbs.Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Dead branches within shrubs are common and standing dead shrub canopy material may be as much as 35% of total shrub canopy; mature bunchgrasses (<25%) may have dead centers. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Herbaceous litter within interspaces (± 5%) and litter depth is ± ¼ inch. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

For normal or average growing season (through May) ± 200 lbs/ac. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Increasers include Douglas rabbitbrush. Invaders include Russian thistle, annual mustards, and cheatgrass. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All functional groups should reproduce in average (or normal) and above average growing season years.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.