Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F029XY058NV

PIMO-JUOS WSG 0R0507 10 to 15

Accessed: 03/12/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 029X–Southern Nevada Basin and Range

MLRA 29 consists of north-south trending mountain ranges separated by broad valleys bordered by sloping fans and pediments. Majority of rocks in the mountain masses are from Pliocene and Miocene volcanic sources and include rhyolite, andesite, basalt, dacite and tuff. Paleozoic and Precambrian carbonate rocks are also prominent in the mountains. Scattered outcrops of older Tertiaty intrusives and very young tuffaceous sediments are common in the western and eastern portions of the MLRA. Pleistocene lake sediments and recent alluvium are extensive in the major valleys.

More than 90 percent of MLRA 29 is federally owned, a large portion of which is currently or has been used for training and testing by military forces and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Less than 1 percent of the land area, mostly in the valleys, is irrigated. Most of the irrigated land is used for growing grain or hay for livestock. Native shrub-grass rangelands are grazed by domestic livestock, feral horses and wildlife. Average annual precipitation ranges from 4 to 12 inches on the valley floors and may be as high as 36 inches in the mountains. Precipitation occurs as rain and snow during the winter and early spring. Summers are generally hot and dry, but high-intensity, convective thunderstorms are common in July and August. In the eastern portion of this MLRA these summer thunderstorms are frequent enough to influence annual production and species composition of many native plant communities.

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Pinus monophylla |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Purshia stansburiana |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Pyrrocoma |

Physiographic features

This Forest site occurs on mountain and hill sideslopes and summits on all aspects. Slope gradients are from 8 to 30 percent. Elevations are 5600 to about 7000 feet.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Fan remnant

|

|---|---|

| Elevation | 1,707 – 2,134 m |

| Slope | 8 – 30% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

Average annual precipitation is 10 to about 14 inches. Mean annual air temperature is 45 to 50 degrees F. The average frost-free period is 80 to 120 days.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 120 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 0 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 356 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Influencing water features

There are no influencing water features associated with this site.

Soil features

The soils associated with this site range from very shallow to deep and are well drained. Very shallow soils support this site where there are high amounts of stones or boulders at the soil surface and there are many fractures and crevices within the bedrock material. The soils are skeletal with 35 to 50 percent gravels, cobbles or stones, by volume, distributed throughout their profile. Available water capacity is low, but trees and shrubs extend their roots into fractures in the bedrock allowing them to utilize deep moisture. Runoff is medium to rapid and potential for sheet and rill erosion is moderate to severe depending on slope. The soil series associated with this site is Morebench.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Gravelly sandy loam |

|---|---|

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate |

| Soil depth | 183 – 213 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 25 – 40% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 3 – 5% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

6.86 – 7.11 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

5 – 25% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 1 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

7.9 – 9 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

25 – 48% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

3 – 5% |

Ecological dynamics

Major Successional Stages of Forestland Development:

HERBACEOUS: Vegetation is dominated by grasses and forbs under full sunlight. This stage is experienced after a major disturbance such as crown fire. Skeleton forest (dead trees) remaining after fire or residual trees left following harvest have little or no affect on the composition and production of the herbaceous vegetation.

SHRUB-HERBACEOUS: Herbaceous vegetation and woody shrubs dominate the site. Various amounts of tree seedlings (less than 20 inches in height) may be present up to the point where they are obviously a major component of the vegetal structure.

SAPLING: In the absence of disturbance the tree seedlings develop into saplings (20 inches to 4.5 feet in height) with a range in canopy cover of about 5 to 10 percent. Vegetation consists of grasses, forbs and shrubs in association with tree saplings. The visual aspect and vegetal structure are dominated by Utah juniper trees greater than 4.5 feet in height. The upper crown of dominant and co-dominant trees are cone or pyramidal shaped. Seedlings and saplings of pinyon and Utah juniper are present in the understory. Dominants are the tallest trees on the site; co-dominants are 65 to 85 percent of the highest of dominant trees. Understory vegetation is moderately influenced by a tree overstory canopy of about 10 to 20 percent.

MATURE FOREST: The visual aspect and vegetal structure are dominated by singleleaf pinyon and Utah juniper that have reached or are near maximal heights for the site. Dominant trees average greater than five inches in diameter at one-foot stump height. Upper crowns of singleleaf pinyon and Utah juniper are typically either irregularly or smoothly flat-topped or rounded. Tree canopy cover ranges from 20 to 35 percent. Understory vegetation is strongly influenced by tree competition, overstory shading, duff accumulation, etc. Few tree seedlings and/or saplings occur in the understory. Infrequent, yet periodic, wildfire is presumed to be a natural factor influencing the understory of mature pinyon-juniper woodlands. This stage of community development is assumed to be representative of this woodland site in the pristine environment.

OVER-MATURE FOREST: In the absence of wildfire or other naturally occurring disturbances, the tree canopy on this site can become very dense. This stage is dominated by singleleaf pinyon and Utah juniper that have reached maximal heights for the site. Dominant and co-dominant trees average greater than five inches in diameter at one-foot stump height. Upper crowns are typically irregularly flat-topped or rounded. Understory vegetation is sparse or absent due to tree competition, overstory shading, duff accumulation, etc. Tree canopy cover is commonly greater than 50 percent.

Ecological Dynamics:

The pinyon-juniper forestland is generally a climax vegetation type throughout its range, reaching climax about 300 years after disturbance, with an ongoing trend toward increased tree density and canopy cover and a decline in understory species over time. Singleleaf pinyon seedling establishment is episodic. Population age structure is affected by drought, which reduces seedling and sapling recruitment more than other age classes. The ecotones between singleleaf pinyon woodlands and adjacent shrublands and grasslands provide favorable microhabitats for singleleaf pinyon seedling establishment since they are active zones for seed dispersal, nurse plants are available, and singleleaf pinyon seedlings are only affected by competition from grass and other herbaceous vegetation for a couple of years.

Several natural and anthropogenic processes can lead to changes in the spatial distribution of pinyon-juniper woodlands over time. These include 1) tree seedling establishment during favorable climatic periods, 2) tree mortality (especially seedlings and saplings) during periods of drought, 3) expansion of trees into adjacent grassland in response to overgrazing and/or fire suppression, and 4) removal of trees by humans, fire, or other disturbance episodes. Specific successional pathways after disturbance in singleleaf pinyon stands are dependent on a number of variables such as plant species present at the time of disturbance and their individual responses to disturbance, past management, type and size of disturbance, available seed sources in the soil or adjacent areas, and site and climatic conditions throughout the successional process.

Fire Ecology:

On high-productivity sites where sufficient fine fuels existed, singleleaf pinyon communities burn every 15 to 20 years, and on less productive sites with patchy fuels, fire return intervals may be in the range of 50 to 100 years or longer. Thin bark and lack of self pruning make singleleaf pinyon very susceptible to intense fire. Mature singleleaf pinyon can survive low-severity surface fires but is killed by more severe fires. Most tree seedlings are killed by fire, but cached seeds may survive. The fire return intervals for Utah juniper communities range from 10 to 30 years. Utah juniper is usually killed by fire, especially when trees are small. Fire effects on Stansbury cliffrose are variable. Fire may kill or severely damage plants. Late-season fire also increases the risk of mortality. Stansbury cliffrose is a weak sprouter that is generally killed by severe fire. Fires top-kill mountain snowberry. Although plant survival may be variable, mountain snowberry root crowns usually survive even severe fires. Mountain snowberry sprouts from basal buds at the root crown following fire. Muttongrass is unharmed to slightly harmed by light-severity fall fires. Muttongrass appears to be harmed by and slow to recover from severe fire. Indian ricegrass can be killed by fire, depending on severity and season of burn. Indian ricegrass reestablishes on burned sites through seed dispersed from adjacent unburned areas. Sandberg bluegrass is generally unharmed by fire. It produces little litter, and its small bunch size and sparse litter reduces the amount of heat transferred to perennating buds in the soil. Its rapid maturation in the spring also reduces fire damage, since it is dormant when most fires occur. Bottlebrush squirreltail's small size, coarse stems, and sparse leafy material aid in its tolerance of fire. Postfire regeneration occurs from surviving root crowns and from on- and off-site seed sources. Frequency of disturbance greatly influences postfire response of bottlebrush squirreltail. Undisturbed plants within a 6 to 9 year age class generally contain large amounts of dead material, increasing bottlebrush squirreltail's susceptibility to fire. Sedge is top-killed by fire, with rhizomes protected by insulating soil. The rhizomes of sedge species may be killed by high-severity fires that remove most of the soil organic layer. Reestablishment after fire occurs by seed establishment and/or rhizomatous spread. Galleta is a rhizomatous perennial which can resprout after top-kill by fire. Blue grama has variable fire tolerance; it has fair tolerance when dormant but experiences some damage if burned during active growth, especially during drought. Fire generally favors blue grama, generally increasing its occurrence, production, and percent cover.

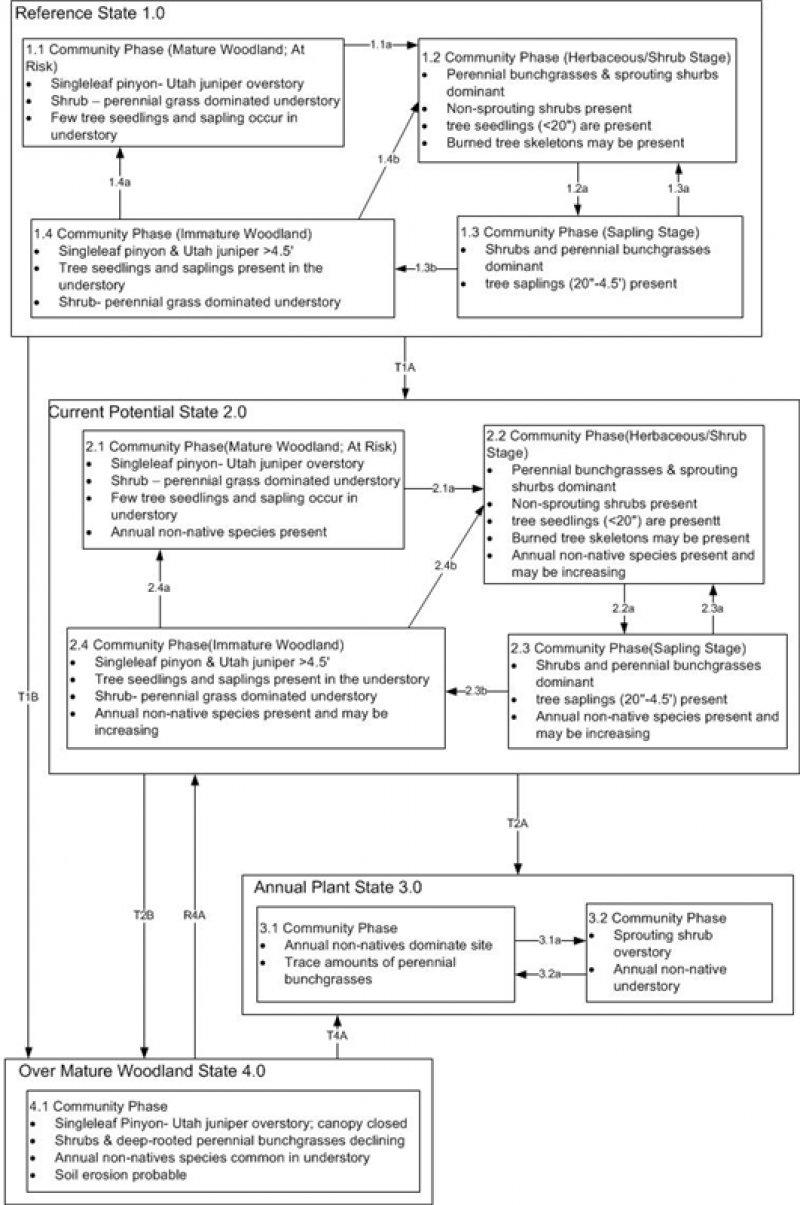

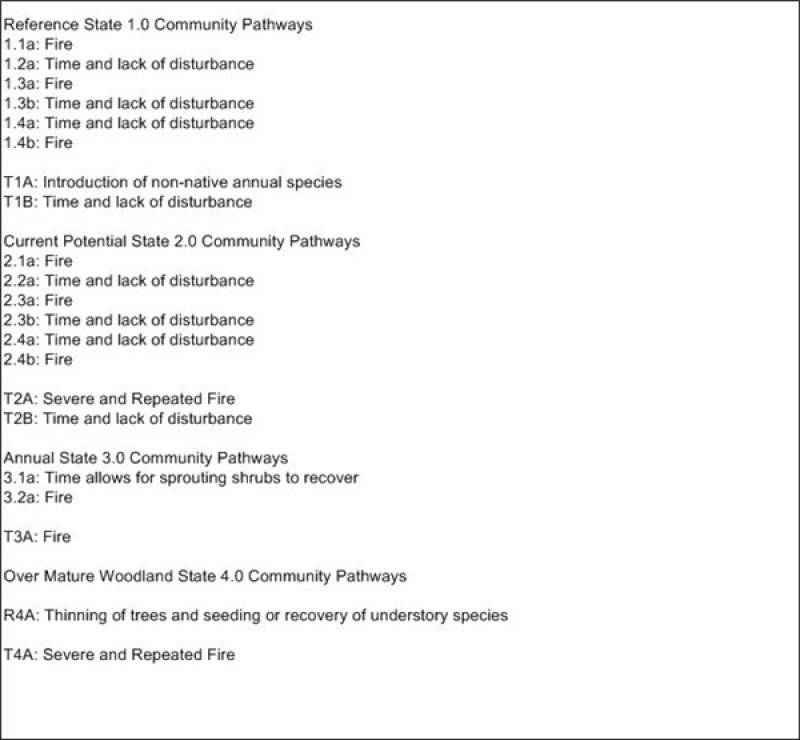

State and transition model

Figure 3. DRAFT STM

Figure 4. DRAFT STM LEGEND

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State

Community 1.1

Reference Community Phase (mature woodland)

The reference plant community is dominated by singleleaf pinyon and Utah juniper. Stansbury cliffrose and desert snowberry are the principal understory shrubs. Goldenweed is the dominant understory forb while muttongrass and Sandberg bluegrass are the most prevalent understory grasses. Overstory tree canopy composition is about 20 to 40 percent Utah juniper and 60 to 80 percent singleleaf pinyon. An overstory canopy cover of 20 to 35 percent is assumed to be representative of tree dominance on this site in the pristine environment.

Forest overstory. MATURES FOREST: The visual aspect and vegetal structure are dominated by singleleaf pinyon and Utah juniper that have reached or are near maximal heights for the site. Dominant trees average greater than five inches in diameter at one-foot stump height. Upper crowns of singleleaf pinyon and Utah juniper are typically either irregularly or smoothly flat-topped or rounded. Tree canopy cover ranges from 20 to 35 percent. Understory vegetation is strongly influenced by tree competition, overstory shading, duff accumulation, etc. Few tree seedlings and/or saplings occur in the understory. Infrequent, yet periodic, wildfire is presumed to be a natural factor influencing the understory of mature pinyon-juniper forestlands. This stage of community development is assumed to be representative of this woodland site in the pristine environment.

Forest understory. Understory vegetative composition is about 20 percent grasses, 15 percent forbs and 65 percent shrubs and young trees when the average overstory canopy is medium (20 to 35 percent). Average understory production ranges from 50 to 200 pounds per acre with a medium canopy cover. Understory production includes the total annual production of all species within 4.5 feet of the ground surface.

Figure 5. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 34 | 84 | 135 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 11 | 28 | 45 |

| Forb | 9 | 21 | 34 |

| Tree | 2 | 7 | 11 |

| Total | 56 | 140 | 225 |

Community 1.2

Herbaceous/Shrub

Community 1.3

Sapling

Community 1.4

Immature Woodland

State 2

Current Potential State

State 3

Annual Plant State

State 4

Over Mature Woodland State

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Primary Perennial Grasses | 13–25 | ||||

| muttongrass | POFE | Poa fendleriana | 7–12 | – | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 7–12 | – | ||

| 2 | Secondary Perennial Grasses | 3–22 | ||||

| Indian ricegrass | ACHY | Achnatherum hymenoides | 1–7 | – | ||

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | 1–7 | – | ||

| squirreltail | ELEL5 | Elymus elymoides | 1–7 | – | ||

| James' galleta | PLJA | Pleuraphis jamesii | 0–1 | – | ||

| blue grama | BOGR2 | Bouteloua gracilis | 0–1 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | Perennial | 9–84 | ||||

| goldenweed | PYRRO | Pyrrocoma | 7–71 | – | ||

| desertparsley | LOMAT | Lomatium | 1–7 | – | ||

| phlox | PHLOX | Phlox | 1–7 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 4 | Primary Shrubs | 7–12 | ||||

| Stansbury cliffrose | PUST | Purshia stansburiana | 7–12 | – | ||

| 5 | Secondary Shrubs | 1–7 | ||||

| desert snowberry | SYLO | Symphoricarpos longiflorus | 1–7 | – | ||

|

Tree

|

||||||

| 6 | Evergreen | 8–19 | ||||

| singleleaf pinyon | PIMO | Pinus monophylla | 7–12 | – | ||

| Utah juniper | JUOS | Juniperus osteosperma | 1–7 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Livestock Interpretations:

This site is not well suited to cattle or sheep grazing due to low productivity of understory forage plants. Livestock will often concentrate on this site taking advantage of the shade and shelter offered by the tree overstory. Many areas are not used because of steep slopes and lack of adequate water. Attentive grazing management is required due to steep slopes and associated erosion hazards. Harvesting trees under a sound management program for fuelwood, posts or other products can open the tree canopy to allow increased production of understory species desirable for grazing.

Stocking rates vary with such factors as kind and class of grazing animal, season of use and fluctuations in climate. Actual use records for individual sites, a determination of the degree to which the sites have been grazed, and an evaluation of trend in site condition offer the most reliable basis for developing initial stocking rates.

Selection of initial stocking rates for given grazing units is a planning decision. This decision should be made ONLY after careful consideration of the total resources available, evaluation of alternatives for use and treatment, and establishment of objectives by the decisionmaker.

The forage value rating is not an ecological evaluation of the understory as is the range condition rating for rangeland. The forage value rating is a utilitarian rating of the existing understory plants for use by specific kinds of grazing animals.

Muttongrass is excellent forage for domestic livestock especially in the early spring. Muttongrass begins growth in late winter and early spring, which makes it available before many other forage plants. Indian ricegrass is highly palatable to all classes of livestock in both green and cured condition. It supplies a source of green feed before most other native grasses have produced much new growth. Sandberg bluegrass is a widespread forage grass. It is one of the earliest grasses in the spring and is sought by domestic livestock and several wildlife species. Sandberg bluegrass is a palatable species, but its production is closely tied to weather conditions. It produces little forage in drought years, making it a less dependable food source than other perennial bunchgrasses. Bottlebrush squirreltail is very palatable winter forage for domestic sheep of Intermountain ranges. Domestic sheep relish the green foliage. Overall, bottlebrush squirreltail is considered moderately palatable to livestock. Sedge provides good to fair forage for domestic grazing. When actively growing, galleta provides good to excellent forage for cattle and horses and fair forage for domestic sheep. Although not preferred, all classes of livestock may use galleta when it is dry. Domestic sheep show greater use in winter than summer months and typically feed upon central portions of galleta tufts, leaving coarser growth around the edges. Galleta may prove somewhat coarse to domestic sheep. Blue grama is valuable forage for all classes of domestic livestock, providing excellent forage for cattle and sheep. Blue grama tends to be most productive following summer rains, but it cures well and provides forage year round. Stansbury cliffrose is an important browse species for livestock, especially in the winter. Since desert snowberry leafs out in early spring it is utilized by all browsing animals at that time but, in general, use is very limited. Pinyon-juniper woodlands are considered to have poor palatability for cattle, sheep, and horses. Utah juniper is used by and livestock for cover and food.

Wildlife Interpretations:

This site has high value for mule deer during the winter. Juniper trees provide shelter from winter storms and juniper foliage is also browsed during the winter. Sites where water is available offer good quail habitat and are visited seasonally by mourning dove. It is also used by various song birds, rodents, reptiles and associated predators natural to the area.Stansbury cliffrose is an important browse species for mule deer, pronghorn, game birds, and songbirds. Wild ungulates use it heavily in winter.Desert snowberry is browsed by deer and livestock and the seeds are eaten by birds, especially the gallinaceous birds such as ring-necked pheasants, grouse, and quail. Sage-grouse in Nevada utilize desert snowberry as both juveniles and adults. The American pika and various ground squirrels also eat the seeds. Pinyon-juniper woodlands provide shelter and forage for numerous species of wildlife, some of which may be obligate to these woodlands such as pinyon mice and woodrats. These forests have value as habitat for several large mammals such as mule deer, pronghorn, desert bighorn sheep, elk, wild horses, mountain lions, and bears. Gray foxes, bobcats, coyotes, weasels, skunks, and badgers search for prey here. Many species of birds and reptiles find food and shelter here.

Utah juniper is used by many birds and wildlife for cover and food. The foliage is grazed by mule deer when other foliage is scarce and during periods of deep snow. Juniper "berries" or berry-cones are eaten by jackrabbits and coyotes. Many bird species depend on juniper berry-cones for fall and winter food. Desert snowberry is used "lightly" in all seasons but winter, when it is not utilized by mule deer. Limited summer use of desert snowberry by pronghorns in has been observed. Cover value of desert snowberry for big game is limited by its size. However, it provides fair cover for both upland game birds and small nongame birds and good cover for small mammals. Deer and elk make heavy use of muttongrass, especially in early spring when other green forage is scarce. Depending upon availability of other nutritious forage, deer may use mutton grass in all seasons. Mutton grass cures well and is an important fall and winter deer food in some areas. Indian ricegrass is eaten by pronghorn in "moderate" amounts whenever available. In Nevada it is consumed by desert bighorns. A number of heteromyid rodents inhabiting desert rangelands show preference for seed of Indian ricegrass. Indian ricegrass is an important component of jackrabbit diets in spring and summer. In Nevada, Indian ricegrass may even dominate jackrabbit diets during the spring through early summer months. Indian ricegrass seed provides food for many species of birds. Doves, for example, eat large amounts of shattered Indian ricegrass seed lying on the ground. Sandberg bluegrass is desirable for pronghorn antelope and mule deer in the spring and preferable in the spring, summer, and fall for elk and desirable as part of their winter range. Bottlebrush squirreltail is a dietary component of several wildlife species. Bottlebrush squirreltail may provide forage for mule deer and pronghorn. Sedges have a high to moderate resource value for elk and a medium value for mule deer. Elk consume beaked sedge later in the growing season. Galleta provides moderately palatable forage when actively growing and relatively unpalatable forage during dormant periods. Galleta provides poor cover for most wildlife species. Blue grama also provides important forage for mule deer. Quail and some songbirds eat the seeds of blue grama. Small mammals also eat blue grama seeds and stems. Flower heads and seeds of blue grama are also consumed by grasshoppers, which can all but eliminate an annual seed crop.

Hydrological functions

The hydrologic cover condition of this site is poor in a representative stand. The average runoff curve is about 85 for group C soils and about 90 for group D. Soils.

Recreational uses

The trees on this site provide a welcome break in an otherwise open landscape. It has potential for hiking, cross-country skiing, camping, and deer and upland game hunting.

Wood products

PRODUCTIVE CAPACITY

This forestland community is of low site quality for tree production. Site index ranges from 35 to 55 (Howell, 1940).

Productivity Class: 0.2 to 0.4

CMAI*: 3.3 to 5.2 ft3/ac/yr;

0.23 to 0.36 m3/ha/yr.

Culmination is estimated to be at 100 years.

*CMAI: is the culmination of mean annual increment or highest average growth rate of the stand in the units specified.

Fuelwood Production: 4 to 7 cords per acre for stands averaging 5 inches in diameter at 1 foot height with a medium canopy cover. There are about 289,000 gross British Thermal Units (BTUs) heat content per cubic foot of pinyon pine wood and about 274,000 gross BTUs heat content per cubic foot of Utah juniper. Solid wood volume in a cord varies but usually ranges from 65 to 90 cubic feet. Assuming an average of 75 cubic feet of solid wood per cord, there are about 21 million BTUs of heat value in a cord of mixed pinyon pine and Utah juniper.

Posts (7 foot): About 15 to 25 posts per acre in stands of medium canopy.

Christmas trees: 5 trees per acre per year in stands of medium canopy. Ten trees per acre in stands of sapling stage.

Pinyon nuts: Production varies year to year, but mature woodland stage can yield 150 to 200 pounds per acre in favorable years.

1. LIMITATIONS AND CONSIDERATIONS

a. Potential for sheet and rill erosion is moderate to severe depending on slope.

b. Moderate equipment limitations on steeper slopes and moderate to severe equipment limitations on sites having extreme surface stoniness.

c. Proper spacing is the key to a well managed, multiple use and multi-product pinyon-juniper forestland.

2. ESSENTIAL REQUIREMENTS

a. Adequately protect from wildfire.

b. Protect soils from accelerated erosion.

c. Apply proper grazing management.

3. SILVICULTURAL PRACTICES

Silvicultural treatments are not reasonably applied on this site due to poor site quality and severe limitations for equipment and tree harvest.

Other products

The pitch of singleleaf pinyon was used by Native Americans as an adhesive, caulking material, and a paint binder. It may also be used medicinally and chewed like gum. Pinyon seeds are a valuable food source for humans, and a valuable commercial crop. These trees have provided Indians with food for centuries. Thousands of pounds of nuts are gathered each year and sold on the markets throughout the United States. The berries have been used by Indians for food. Triterpenoids extracted from Stansbury cliffrose have been shown to have inhibitory effects on HIV and Epstein-Barr virus. Native Americans used the inner bark for making clothing and ropes, and the branches for making arrows.

Indian ricegrass was traditionally eaten by some Native Americans. The Paiutes used seed as a reserve food source.

Other information

Pinyon wood is rather soft, brittle, heavy with pitch, and yellowish brown in color. Singleleaf pinyon has played an important role as a source of fuelwood and mine props. It has been a source of wood for charcoal used in ore smelting. It still has a promising potential for charcoal production. Other important uses for this tree are for Christmas trees and as a source of nuts for wildlife and human food. Utah juniper wood is very durable. Its primary uses have been for posts and fuelwood. It probably has considerable potential in the charcoal industry and in wood fiber products. Bottlebrush squirreltail is tolerant of disturbance and is a suitable species for revegetation. Because of its wide adaptation, ease of establishment, and economic value, blue grama is used extensively for conservation purposes, rangeland seeding, and landscaping. Stansbury cliffrose is recommended for wildlife, roadside, construction, and mine spoils plantings; and for restoring pinyon-juniper woodland, mountain brushland, basin big sagebrush grassland, black sagebrush, and black greasewood communities. It can be established on disturbed seedbeds by broadcast seeding, drill seeding, or transplanting. Fall or winter seeding is recommended. Blue grama is useful for reclamation and for erosion control in arid and semiarid regions.

Supporting information

Type locality

| Location 1: White Pine County, NV | |

|---|---|

| Township/Range/Section | T14N R61E S28 |

| General legal description | About 2½ miles northeast of Morey Peak, along road to Morey (town site), Hot Creek Range, Nye County, Nevada. This site also occurs in Clark, Lincoln, and Nye Counties, Nevada. |

Other references

Howell, J., 1940. Pinyon and juniper: a preliminary study of volume, growth, and yield. Regional Bulletin 71. Albuquerque, NM: USDA, SCS; 90p.

Jordan, M., 1974. An Inventory of Two Selected Woodland Sites in the Pine Nut Hills of Western Nevada.

USDA-NRCS. 1980. National Forestry Manual - Part 537. Washington, D.C.

Contributors

GED/RRK

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.