Ecological dynamics

Following are descriptions of several plant communities that may occupy this site. The interpretive community described in the plant community tables is the Historical Climax Plant Community (HCPC). This community is represented by a level to rolling grassland dominated by cool season bunchgrasses, with several species of forbs occurring in small percentages. Minor variations in the plant community will occur as an expression of climatic patterns, topography and landform, elevation, soils, fire pattern and history, and grazing.

#1 -- HCPC -- Tall and Medium Grasses with Forbs.

This is the interpretive plant community and is considered to be the Historic Climax Plant Community (HCPC) for this site. This plant community contains a high diversity of tall and medium height, cool season grasses (rough fescue, bluebunch wheatgrass, Idaho fescue, green/Columbia/Letterman’s/western needlegrass, bearded/slender wheatgrass, porcupinegrass, mountain brome) and short grasses (Cusick and Sandberg bluegrass, spike oatgrass, and prairie junegrass). There are abundant forbs (geranium, prairie clovers) which occur in smaller percentages.

This plant community is well adapted to the Northern Rocky Mountain Foothills climatic conditions. The diversity in plant species allows for drought tolerance. Individual species can vary greatly in production depending on growing conditions (i.e., timing and amount of precipitation, and temperature). It is well suited to managed livestock grazing and provides diverse habitat for many wildlife species.

These plants have strong, healthy root systems that allow production to increase significantly with favorable growing conditions. This plant community provides for soil stability and a properly functioning hydrologic cycle. Abundant plant litter is available for soil building and moisture retention. Plant litter is properly distributed with very little movement off-site and natural plant mortality is very low. The soils associated with this site provide a very favorable soil-water-plant relationship.

#2 -- Medium and Short Grasses with Forbs

Early stages of degradation, including non-prescribed grazing, will tend to change the HCPC to a community dominated by medium and short grasses such as Idaho fescue, needleandthread (mainly 15 inches MAP or less), thickspike/western wheatgrass, Cusick and Sandberg bluegrass, spike oatgrass, and prairie junegrass,. Most of the taller, more palatable grasses (rough fescue, bluebunch wheatgrass, tall needlegrasses, porcupinegrass) will still be present but in smaller amounts. Palatable and nutritious forbs will begin to be replaced by less desirable and more aggressive species such as lupine and stoneseed.

#3 -- Medium & Short Grasses/Forbs/Non-Native Grasses

Given the right circumstances and opportunity, non-native grasses such as Kentucky/Canada bluegrass or common timothy will become established on this ecological site. In this situation, slight degradation in the historical climax plant community results in a plant community similar to #2, except that it will also have these non native plants as minor components. If further degradation continues, these species will continue to increase and replace other, more desirable native species.

Biomass production and litter become slightly reduced on the site with Communities 2 and 3, as the taller grasses become replaced by shorter ones, especially the non-native grasses. Evapotranspiration tends to increase, moisture retention is reduced, and soil surface temperatures increase. Some natural ecological processes will be altered. These plant communities provide for moderate soil stability. Increased amounts of bare ground can result in undesirable species invading. Common invaders can include leafy spurge, dalmation toadflax, and sulphur cinquefoil.

The following plant communities are the result of long-term, heavy, continuous season long grazing and/or heavy, annual, early spring grazing. Repeated spring grazing depletes stored carbohydrates, resulting in weakening and eventual death of the cool season tall and medium grasses. These plant communities can occur throughout the pasture, on spot grazed areas, and near water sources where season-long grazing patterns occur.

It is critical at this point to consider implementing a change in grazing management to prevent further degradation to any of the following plant communities and minimize the increase of less desirable and non native species. Once any of the following communities become established, the potential to return to communities 1, 2, or 3 is reduced and often requires a significant amount of time along with economic inputs.

#4 -- Idaho Fescue, Short Grasses/Sageworts/Forbs

With continued heavy disturbance on community 2, the site will become dominated by species such as Idaho fescue, thickspike or western wheatgrass, Parry danthonia, prairie junegrass, sedges, needleandthread (15 inches MAP or less), fringed and/or cudweed sagewort, and perennial forbs such as lupine, western yarrow, prairie smoke and ballhead sandwort. There may still be remnant amounts of some of the late-seral species such as bluebunch wheatgrass and green/Columbia needlegrass present. The taller grasses will occur only occasionally, often within horizontal juniper plants. Palatable forbs will be mostly absent. Shrubby cinquefoil can become a significant component, particularly in the higher moisture areas (> 17 inches precipitation) of this MLRA/RRU.

#5 -- Mid & Short Grasses/Sedges/Non-Native Grasses

As heavy disturbance continues, plant community 3 deteriorates to one similar to community number 4, except that non-native bluegrasses (Kentucky/Canada) and/or common timothy become more abundant, often comprising up to about 25 percent of the composition.

Plant communities 4 & 5 are often less productive than Plant Communities 1, 2, or 3. The lack of litter and short plant heights result in higher soil temperatures, poor water infiltration rates, and higher evapotranspiration rates, thus eventually favoring species that are more adapted to drier conditions. These communities have lost many of the attributes of a healthy rangeland, including good infiltration, minimal erosion and runoff, nutrient cycling and energy flow.

Communities 4 and 5 will respond positively to improved grazing management, but significant economic inputs and time will usually also be needed to move them toward a higher successional stage. Once plants such as Kentucky or Canada bluegrass or timothy become established, they are very difficult to remove and replace by grazing management alone. Additionally, the chances for success are significantly reduced.

#6 -- Weedy Forbs/Sageworts/Short Grasses/Creeping Juniper

If community 4 deteriorates further due to non-prescribed grazing or other disturbance, it becomes dominated by weedy forbs (pussytoes, cudweed sagewort, western yarrow, prairie smoke, field chickweed, northern bedstraw and ballhead sandwort), short grasses (Sandberg bluegrass, and prairie junegrass), and half shrubs such as fringed sagewort. There is often a remnant amount of some of the mid-seral grasses such as thickspike wheatgrass and Idaho fescue, usually widely spaced. Creeping juniper can become abundant in the northern part of this MLRU. Frequently, a remnant population of climax species such as rough fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass will occur within the creeping juniper.

#7 -- Non-Native Grasses/Weedy Forbs/Clubmoss

Further deterioration of community 5 due to non-prescribed grazing or other disturbance leads to a plant community dominated by Kentucky/Canada bluegrass and/or common timothy, often comprising 25 to 80 % of the community. Weedy forbs including field chickweed, cudweed sagewort, and pussytoes are abundant and typically comprise the rest of the plant composition. A thick cover of dense clubmoss often completes this community. Occasionally, in places receiving 17 inches or greater precipitation, some short lived native species such as mountain brome can become dominant after major disturbance from grazing or rodent (pocket gopher mainly) activity.

Plant communities 6 and 7 have extremely reduced production of desirable native plants. The lack of litter and short plant heights result in higher soil surface temperatures, poor water infiltration rates, and increased evaporation, which gives short grasses, weedy forbs, and invader species a competitive advantage over the cool season tall and medium grasses. These communities have lost most of the attributes of a healthy rangeland, including good infiltration, minimal runoff and erosion, nutrient cycling and energy flow.

Significant economic inputs such as seeding and/or mechanical treatment practices are needed, along with extended rest and prescribed grazing management, to restore these plant communities to a higher successional stage.

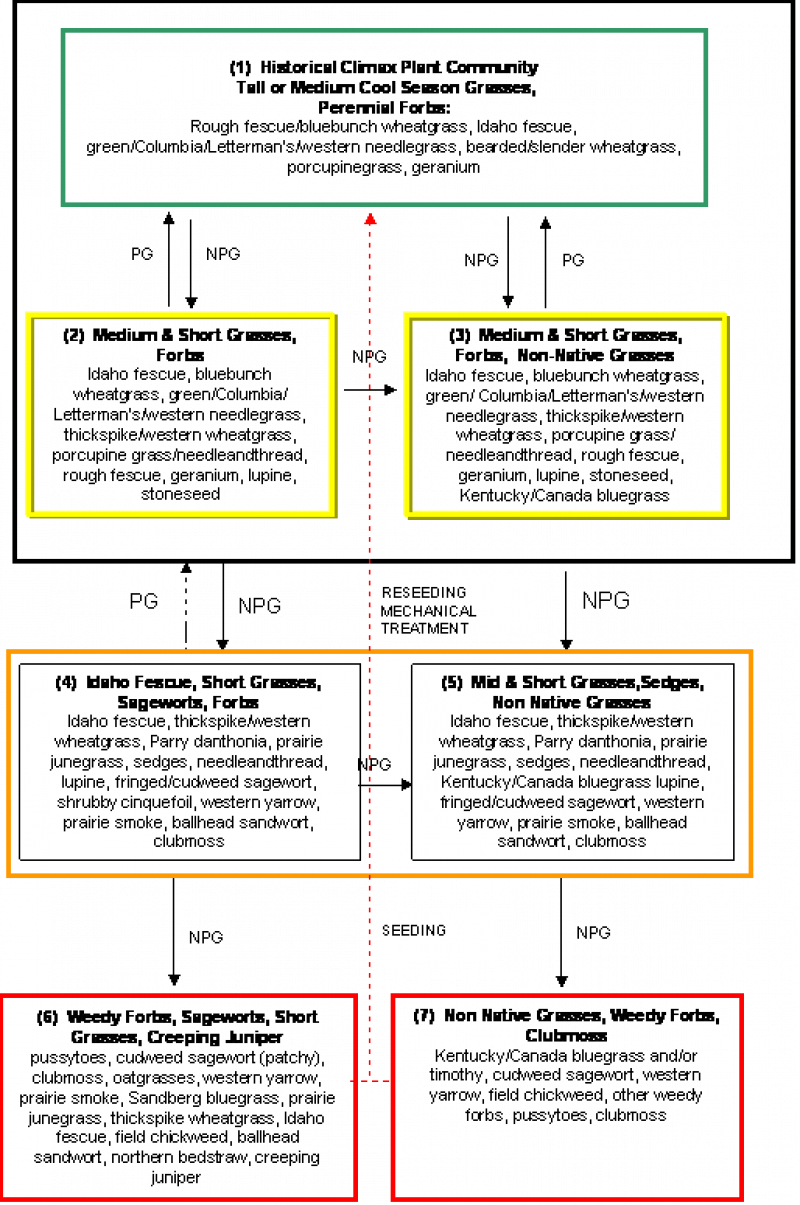

STATE AND TRANSITION MODEL DIAGRAM NOTES:

1. Kentucky and Canada bluegrass and common timothy can become a part of any plant community in this ecological site, depending on factors such as site history, circumstances, and the opportunity for these plants to establish. Generally, the percent composition of these will increase as the ecological condition degrades until they will become dominant.

2. Smaller boxes within a larger box indicate that these communities will normally shift among themselves with slight variations in precipitation and other disturbances. Moving outside the larger box indicates the community has crossed a threshold (heavier line) and will require intensive treatment to return to Community 1, 2 or 3.

3. Dotted lines indicate a reduced probability for success.

4. Yellow boxes (around Communities 2 & 3 individually) indicate caution that the community may be in danger of crossing a threshold.

5. Orange boxes (grouping Communities 4 & 5)represent communities that have crossed over thresholds from the HCPC and may be difficult to restore with grazing management alone.

6. Red boxes (around Communities 6 & 7 individually) represent communities that have severely shifted away from the HCPC and probably cannot be restored without mechanical inputs.

7. Not all species present in the community are listed in this table. Species listed are representative of the plant functional groups that occur in the community.

LEGEND:

PG = Prescribed Grazing: Use of a planned grazing strategy to balance animal forage demand with available forage resources. Timing, duration, and frequency of grazing are controlled and some type of grazing rotation is applied to allow for plant recovery following grazing.

NPG = Non-Prescribed Grazing: Grazing which has taken place that does not control the factors as listed above, or animal forage demand is higher than the available forage supply.

MECHANICAL TREATMENT: e.g., chiseling or ripping.

Community 1.1

HCPC -- Tall and Medium Grasses with Forbs.

This is the interpretive plant community and is considered to be the Historic Climax Plant Community (HCPC) for this site. This plant community contains a high diversity of tall and medium height, cool season grasses (rough fescue, bluebunch wheatgrass, Idaho fescue, green/Columbia/Letterman’s/western needlegrass, bearded/slender wheatgrass, porcupinegrass, mountain brome) and short grasses (Cusick and Sandberg bluegrass, spike oatgrass, and prairie junegrass). There are abundant forbs (geranium, prairie clovers) which occur in smaller percentages.

This plant community is well adapted to the Northern Rocky Mountain Foothills climatic conditions. The diversity in plant species allows for drought tolerance. Individual species can vary greatly in production depending on growing conditions (i.e., timing and amount of precipitation, and temperature). It is well suited to managed livestock grazing and provides diverse habitat for many wildlife species.

These plants have strong, healthy root systems that allow production to increase significantly with favorable growing conditions. This plant community provides for soil stability and a properly functioning hydrologic cycle. Abundant plant litter is available for soil building and moisture retention. Plant litter is properly distributed with very little movement off-site and natural plant mortality is very low. The soils associated with this site provide a very favorable soil-water-plant relationship.

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type |

Low

(lb/acre) |

Representative value

(lb/acre) |

High

(lb/acre) |

| Grass/Grasslike |

1310 |

1650 |

1985 |

| Forb |

330 |

465 |

600 |

| Shrub/Vine |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Total |

1640 |

2116 |

2586 |

Table 6. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover |

0%

|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover |

0-5%

|

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover |

75-90%

|

| Forb foliar cover |

1-10%

|

| Non-vascular plants |

0%

|

| Biological crusts |

0-5%

|

| Litter |

0%

|

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" |

0%

|

| Surface fragments >3" |

0%

|

| Bedrock |

0%

|

| Water |

0%

|

| Bare ground |

0%

|

Table 7. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover |

0%

|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover |

0-2%

|

| Grass/grasslike basal cover |

20-25%

|

| Forb basal cover |

1-5%

|

| Non-vascular plants |

0%

|

| Biological crusts |

0-2%

|

| Litter |

60-70%

|

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" |

0-1%

|

| Surface fragments >3" |

0%

|

| Bedrock |

0%

|

| Water |

0%

|

| Bare ground |

0-1%

|

Table 8. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (ft) |

Tree |

Shrub/Vine |

Grass/

Grasslike |

Forb |

| <0.5 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >0.5 <= 1 |

– |

– |

– |

1-10% |

| >1 <= 2 |

– |

0-5% |

75-90% |

– |

| >2 <= 4.5 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >4.5 <= 13 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >13 <= 40 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >40 <= 80 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >80 <= 120 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >120 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Community 1.2

Medium and Short Grasses with Forbs

Early stages of degradation, including non-prescribed grazing, will tend to change the HCPC to a community dominated by medium and short grasses such as Idaho fescue, needleandthread (mainly 15 inches MAP or less), thickspike/western wheatgrass, Cusick and Sandberg bluegrass, spike oatgrass, and prairie junegrass. Most of the taller, more palatable grasses (rough fescue, bluebunch wheatgrass, tall needlegrasses, porcupinegrass) will still be present but in smaller amounts. Palatable and nutritious forbs will begin to be replaced by less desirable and more aggressive species such as lupine and stoneseed.

Community 1.3

Medium & Short Grasses/Forbs/Non-Native Grasses

Given the right circumstances and opportunity, non-native grasses such as Kentucky/Canada bluegrass or common timothy will become established on this ecological site. In this situation, slight degradation in the historical climax plant community results in a plant community similar to #2, except that it will also have these non native plants as minor components. If further degradation continues, these species will continue to increase and replace other, more desirable native species.

Biomass production and litter become slightly reduced on the site with Communities 2 and 3, as the taller grasses become replaced by shorter ones, especially the non-native grasses. Evapotranspiration tends to increase, moisture retention is reduced, and soil surface temperatures increase. Some natural ecological processes will be altered. These plant communities provide for moderate soil stability. Increased amounts of bare ground can result in undesirable species invading. Common invaders can include leafy spurge, dalmation toadflax, and sulphur cinquefoil.

The following plant communities are the result of long-term, heavy, continuous season long grazing and/or heavy, annual, early spring grazing. Repeated spring grazing depletes stored carbohydrates, resulting in weakening and eventual death of the cool season tall and medium grasses. These plant communities can occur throughout the pasture, on spot grazed areas, and near water sources where season-long grazing patterns occur.

It is critical at this point to consider implementing a change in grazing management to prevent further degradation to any of the following plant communities and minimize the increase of less desirable and non native species. Once any of the following communities become established, the potential to return to communities 1, 2, or 3 is reduced and often requires a significant amount of time along with economic inputs.

Community 2.1

Idaho Fescue, Short Grasses/Sageworts/Forbs

With continued heavy disturbance on community 2, the site will become dominated by species such as Idaho fescue, thickspike or western wheatgrass, Parry danthonia, prairie junegrass, sedges, needleandthread (15 inches MAP or less), fringed and/or cudweed sagewort, and perennial forbs such as lupine, western yarrow, prairie smoke and ballhead sandwort. There may still be remnant amounts of some of the late-seral species such as bluebunch wheatgrass and green/Columbia needlegrass present. The taller grasses will occur only occasionally, often within horizontal juniper plants. Palatable forbs will be mostly absent. Shrubby cinquefoil can become a significant component, particularly in the higher moisture areas (> 17 inches precipitation) of this MLRA/RRU.

Community 2.2

Mid & Short Grasses/Sedges/Non-Native Grasses

As heavy disturbance continues, plant community 3 deteriorates to one similar to community number 4, except that non-native bluegrasses (Kentucky/Canada) and/or common timothy become more abundant, often comprising up to about 25 percent of the composition.

Plant communities 4 & 5 are often less productive than Plant Communities 1, 2, or 3. The lack of litter and short plant heights result in higher soil temperatures, poor water infiltration rates, and higher evapotranspiration rates, thus eventually favoring species that are more adapted to drier conditions. These communities have lost many of the attributes of a healthy rangeland, including good infiltration, minimal erosion and runoff, nutrient cycling and energy flow.

Communities 4 and 5 will respond positively to improved grazing management, but significant economic inputs and time will usually also be needed to move them toward a higher successional stage. Once plants such as Kentucky or Canada bluegrass or timothy become established, they are very difficult to remove and replace by grazing management alone. Additionally, the chances for success are significantly reduced.

Community 3.1

Weedy Forbs/Sageworts/Short Grasses/Creeping Juniper

If community 4 deteriorates further due to non-prescribed grazing or other disturbance, it becomes dominated by weedy forbs (pussytoes, cudweed sagewort, western yarrow, prairie smoke, field chickweed, northern bedstraw and ballhead sandwort), short grasses (Sandberg bluegrass, and prairie junegrass), and half shrubs such as fringed sagewort. There is often a remnant amount of some of the mid-seral grasses such as thickspike wheatgrass and Idaho fescue, usually widely spaced. Creeping juniper can become abundant in the northern part of this MLRU. Frequently, a remnant population of climax species such as rough fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass will occur within the creeping juniper.

Community 4.1

Non-Native Grasses/Weedy Forbs/Clubmoss

Further deterioration of community 5 due to non-prescribed grazing or other disturbance leads to a plant community dominated by Kentucky/Canada bluegrass and/or common timothy, often comprising 25 to 80 % of the community. Weedy forbs including field chickweed, cudweed sagewort, and pussytoes are abundant and typically comprise the rest of the plant composition. A thick cover of dense clubmoss often completes this community. Occasionally, in places receiving 17 inches or greater precipitation, some short lived native species such as mountain brome can become dominant after major disturbance from grazing or rodent (pocket gopher mainly) activity.

Plant communities 6 and 7 have extremely reduced production of desirable native plants. The lack of litter and short plant heights result in higher soil surface temperatures, poor water infiltration rates, and increased evaporation, which gives short grasses, weedy forbs, and invader species a competitive advantage over the cool season tall and medium grasses. These communities have lost most of the attributes of a healthy rangeland, including good infiltration, minimal runoff and erosion, nutrient cycling and energy flow.

Significant economic inputs such as seeding and/or mechanical treatment practices are needed, along with extended rest and prescribed grazing management, to restore these plant communities to a higher successional stage.