Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R075XY068NE

Loamy Floodplain

Last updated: 4/17/2025

Accessed: 02/28/2026

General information

Approved. An approved ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model, enough information to identify the ecological site, and full documentation for all ecosystem states contained in the state and transition model.

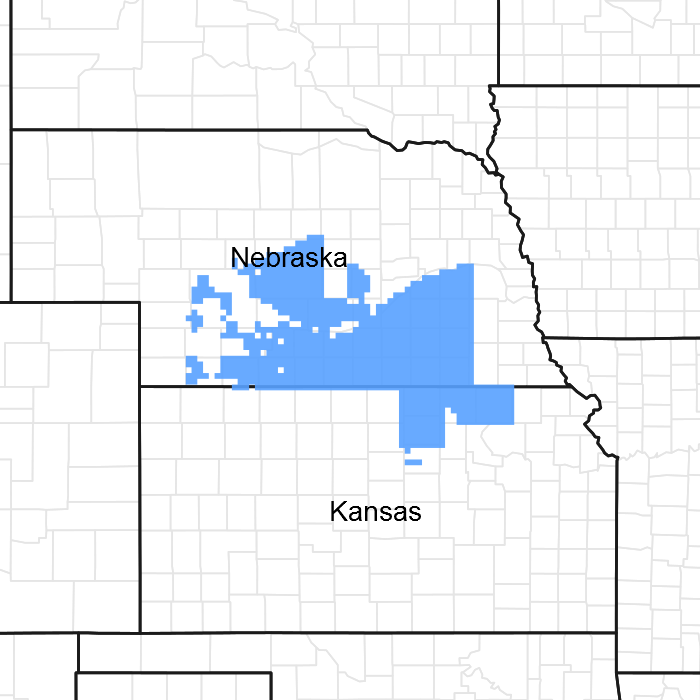

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 075X–Central Loess Plains

Named “The Central Loess Plains,” MLRA 75 is located primarily in south-central Nebraska, with about 10 percent lying in north-central Kansas. This approximately 5.3 million acre landscape covers all or parts of 21 counties: Gosper, Phelps, Kearney, Adams, Clay, Fillmore, York, Hall, Hamilton, Seward, Butler, Polk, Saline, Gge, Harlan, Franklin, Thayer, Nuckolls, and Webster in Nebraska, with a significant presence in Republic and Washington counties in Kansas. This MLRA is home to the unique ecological system called “The Rainwater Basin,” which is comprised of a 24,000 acre network of wetlands and uplands that occupy portions of 13 of the northern counties and is internationally known for its significance to millions of migratory birds.

The landscape primarily consists of gently rolling plains, with a number of narrow, shallow stream valleys. The river valleys are broader, and most feature a number of terraces. The northern border is defined by the Platte River. The elevation in MLRA 75 ranges from nearly 2,600 feet to less than 1,100 feet above sea level. The local relief averages from 10 to 25 feet but may stretch to a maximum of 165 feet in some areas. The average annual precipitation ranges from 23 to 36 inches, and the number of freeze-free days range from 150 to 200.

Loess overlays the surface of almost all of the uplands in this MLRA. Alluvial clay, silt, sand, and gravel are deposited in the stream and river valleys and can be extensive in the major drainages. Terraces are common in the valleys along the river systems. The predominant soil orders in this geographic area are mesic, ustic Mollisols, commonly represented by the Geary, Hastings, Holder, Holdrege, Kenesaw, and Uly soil series. The matrix vegetation type is mixed-grass prairie, with big and little bluestem, switchgrass, Indiangrass, and sideoats and blue grama to make up the bulk of the warm-season species, while western wheatgrass is the dominant cool-season grass.

Seventy two percent of the land in this MLRA has been broken out of native prairie and farmed; the land is primarily planted to corn, wheat, and grain sorghum, while only eighteen percent of the grasslands remain intact. Livestock grazing, primarily by cattle, is the main industry on these remnants. Irrigation of croplands uses over 90 percent of the total annual water withdrawal in this area.

Wildlife flourishes in this combination of crop and grassland environment, with both mule and white-tailed deer being the most abundant wild ungulates. A variety of smaller species, including coyote, raccoon, opossum, porcupines, muskrat, beaver, squirrel, and mink thrive in the region, as well as several upland bird species. Grassland bird populations are somewhat limited by the lack of contiguous native prairie and fragmented habitat created by the farmland. The rivers, streams, and lakes harbor excellent fisheries, and an estimated tens of millions of migrating and local waterfowl use the wetland complexes. These complexes provide ideal habitat for many types of wading and shore bird species as well.

This landscape serves as a backdrop for a disturbance-driven ecosystem, evolving under the influences of herbivory, fire, and variable climate. Historically, these processes created a heterogeneous mosaic of plant communities and structure heights across the region. Any given site in this landscape experienced fire every 6 to 8 years. The fires were caused by lightning strikes and also were set by native Americans, who used fire for warfare, signaling, and to refresh the native grasses. These people understood the value of fire as a tool, and that the highly palatable growth following a fire provided both excellent forage for their horses and attracted grazing game animals such as bison and elk.

Fragmentation of the native grasslands by conversion to cropland, transportation corridors, and other developments have effectively disrupted the natural fire regime of this ecosystem. This has allowed encroachment by native and introduced shrubs and trees into the remnants of the native prairie throughout the MLRA. Aggressive fire suppression policies have exacerbated this process to the point that shrub and tree encroachment is a major ecological issue in the majority of both native and re-seeded grasslands.

Even as post-European settlement's alteration of the fire regime allows the expansion of the woody component of the native prairie, introduction of eastern redcedar (ERC) as a windbreak species further facilitates invasion by this species. While eastern red cedar is native to Nebraska, the historic population in MLRA 75 was limited to isolated pockets in rugged river drainages which were subsequently insulated from fire. Widespread plantings of windbreaks with eastern redcedar as a primary component have provided a seed source for the aggressive woody plant. The ensuing encroachment into the native grasslands degrades the native wildlife habit and causes significant forage loss for domestic livestock.

Since it is not a root sprouter, eastern red cedar is very susceptible to fire when under six feet tall. Management with prescribed fire is exceedingly effective if applied before this stage. Larger redcedars can also be controlled with fire, but successful application requires the use of specifically designed ignition and holding techniques.

Classification relationships

NRCS FOTG Section 1 - Nebraska Vegetation Zone 3.

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 75 (USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006)

Ecological site concept

The Loamy Floodplain site is found on active floodplains subject to inundation. Additional moisture is received as run-on originating from higher on the landscape. Occasional to frequent flooding redistributes soil and plant materials through erosion and deposition and can locally affect production and species composition.

Associated sites

| R075XY058NE |

Loamy Plains This site is located upslope and sometimes adjacent to Loamy Floodplain. |

|---|

Similar sites

| R075XY050NE |

Loamy Terrace This site is located upslope and often adjacent to Loamy Floodplain. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Andropogon gerardii |

Physiographic features

Loamy Floodplain is found on the flood plains of river valleys and in narrow drainage ways of uplands. It receives runoff from areas higher on the landscape and flooding is occasional to frequent. Sedimentation is common.

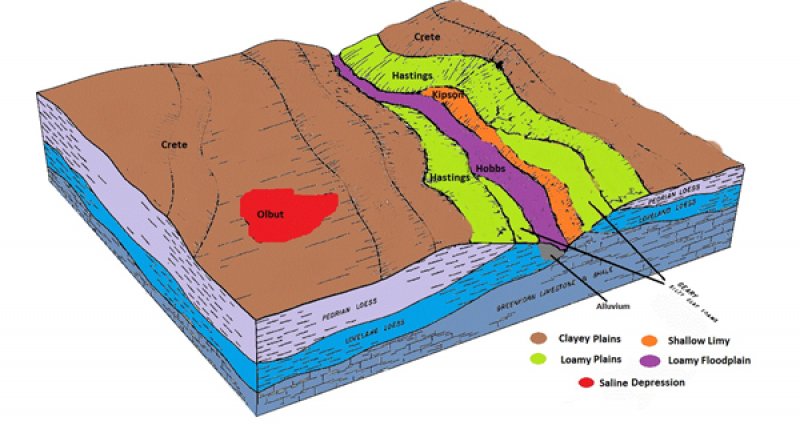

Figure 2. Loamy Floodplain Block Diagram

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Flood plain

(2) Drainageway (3) Swale |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to low |

| Flooding duration | Brief (2 to 7 days) |

| Flooding frequency | Occasional to frequent |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 1,130 – 2,770 ft |

| Slope | 4% |

| Ponding depth | 3 in |

| Water table depth | 80 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

Like most Great Plains landscapes, the climate in this MLRA is under the sway of the continental effect. This creates a regime of extremes, with summer highs often in the triple digits, and winter lows plunging well below zero. Blizzards can occur anytime between early fall and late spring, often dropping the temperature more than 50 degrees in just a few hours. These events can pile up several feet of snow, often driven by winds in excess of 50 miles an hour. The resulting huge snow drifts can cause serious hardship for livestock, wildlife, and humans. Winters can be open, with bare ground for most of the season, or closed, with up to several feet of snow persisting until March. Most winters have a number of warm days, interspersed with dropping temperatures, usually associated with approaching cold fronts. Spring brings violent thunderstorms, hail, high winds, and frequent tornadoes. Daily winds range from an average of 14 miles per hour during the spring to 11 miles per hour during the late summer. Occasional strong storms may bring brief periods of high winds with gusts to more than 80 miles per hour.

Growth of native cool season plants begin in early April and continues to about mid-June. Native warm season plants begin growth in early June and continue to early August. Green up of cool season plants may occur in September and October.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 155 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 177 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 30 in |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BELLEVILLE [USC00140682], Belleville, KS

-

(2) AURORA [USC00250445], Aurora, NE

-

(3) FRIEND 3E [USC00253065], Friend, NE

-

(4) SUPERIOR 4E [USC00258320], Hardy, NE

-

(5) SURPRISE [USC00258328], Surprise, NE

-

(6) CLAY CTR [USC00251684], Saronville, NE

-

(7) FAIRMONT [USC00252840], Fairmont, NE

-

(8) HASTINGS 4N [USC00253660], Hastings, NE

-

(9) HEBRON [USC00253735], Hebron, NE

-

(10) OSCEOLA [USC00256375], Osceola, NE

-

(11) RAGAN [USC00257002], Alma, NE

-

(12) YORK [USC00259510], York, NE

-

(13) GENEVA [USC00253175], Geneva, NE

-

(14) MINDEN [USC00255565], Minden, NE

-

(15) RED CLOUD [USC00257070], Red Cloud, NE

Influencing water features

This site occurs on nearly level areas that receive additional water from overflow of intermittent streams or runoff from adjacent slopes.

Soil features

These very deep soils are subject to inundation by floodwaters and subsequent sedimentation. Most soils are stratified. Textures are dominantly loamy and silty, but sandy textures may occur in the lower part of the root zone. Free water is usually very deep but may be present in the lower part of some profiles during part of the growing season. Organic matter is generally low to moderate in the surface layer.

The major soil series correlated to this ecological site is Hobbs. More information can be found in the various soil survey reports. Contact the local USDA Service Center for internet links to soil survey data that includes more details specific to your location.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Silt loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Moderately well drained to well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow to moderate |

| Soil depth | 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

5.1 – 9.1 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

3% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

6.1 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

Loamy Floodplain sites developed under Northern Great Plains climatic conditions, light to severe grazing by bison and other large herbivores, sporadic natural or man-caused wildfire, and other biotic and abiotic factors that typically influence soil/site development. This continues to be a disturbance-driven site, by herbivory, fire, and variable climate. Changes occur in the plant communities due to short-term weather variations, impacts of native and/or exotic plant and animal species, and management actions. The landscape position and association with streams make this site somewhat less susceptible to fire, which allowed woody species to become more abundant than less sheltered sites in the MLRA.

One of the primary impacts to this site introduced by European-man is season-long continuous grazing by domestic livestock. This management practice causes the repeated removal of the growing point and excessive defoliation of the leaf area of individual warm-season tallgrasses. The resulting reduction of the plants ability to harvest sunlight depletes the root reserves, subsequently decreasing the root mass. This negatively impacts the plants' ability to compete for life sustaining nutrients, resulting in declining vigor, and eventual mortality. The space created in the vegetative community is then occupied by a species that evades the negative grazing impacts by a growing season adaptation (such as a cool-season), a shorter structure or a reduced palatability mechanism.

The State and Transition Model (STM) is depicted below, and is made up of a Reference State, a Native/Invaded State, a Sod-busted State and an Invaded Woody State. Each state represents the crossing of a major ecological threshold due to alteration of the functional dynamic properties of the ecosystem. The main properties observed to determine this change are the soil and vegetative communities, and the hydrological cycle.

Each state may have one or more vegetative communities that fluctuate in species composition and abundance within the normal parameters of the state. Within each state, communities may degrade or recover in response to natural and man caused disturbances such as variation in the degree and timing of herbivory, presence or absence of fire, and climatic and local fluctuations in the precipitation regime. Periodic flooding and deposition events can cause a wide variability in plant communities and production on this site.

Interpretations are primarily based on the Reference State and have been determined by study of rangeland relic areas, areas protected from excessive disturbance, and areas under long-term rotational grazing regimes. Trends in plant community dynamics have been interpreted from heavily grazed to lightly grazed areas, seasonal use pastures, and historical accounts. Plant communities, states, transitional pathways, and thresholds have been determined through similar studies and experience.

Growth of native cool-season plants begins about April 1 and continues to about June 15. Native warm-season plants begin growth about May 15 and continue to about August 15. Green up of cool-season plants may occur in September and October if adequate moisture is available.

The following is a diagram that illustrates the common plant communities that can occur on the site and the transition pathways between communities.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State

This state describes the range of vegetative community phases that occur on the Loamy Floodplain site where the natural processes are mostly intact. The Reference Community is a representation of the native plant community phase that occupies a site that has been minimally altered by management. The Degraded Native Grass Community and the Excessive Litter Community are the phases that result from management decisions that are unfavorable for a healthy Reference Community. The Ephemeral Forb Community is the result of a high intensity disturbance event. High perennial grass cover and production allows for increased soil moisture retention, vegetative production and overall soil quality.

Community 1.1

Reference Community

The Reference Community serves as a description of the native plant community that naturally occurs on the site when the natural disturbance regimes are intact, or closely mimicked by management practices. This phase is dynamic, with fluid relative abundance and spatial boundaries between the dominant structural vegetative groups. These fluctuations are primarily driven by different responses of the species to changes in precipitation timing and abundance, and fire and grazing events. The potential vegetation is approximately 80 to 90 percent grasses and grass-like plants, 2 to 5 percent forbs, and 0 to 5 percent shrubs. The dominant grasses include big bluestem, little bluestem, and Indiangrass. Other grasses and grass-likes include switchgrass and sedges. The forb component is diverse and includes goldenrods, and native legume species. The most common woody species in the plant community are western snowberry and rose. The potential for tree encroachment is high. This plant community is resilient, productive and diverse. This diversity allows for high drought tolerance and promotes a sustainable plant community in regard to site/soil stability, watershed function, and biologic integrity. The Reference Plant Community should exhibit slight to no evidence of rills, wind scoured areas or pedestalled plants. Water flow paths are broken, irregular in appearance or discontinuous with numerous debris dams or vegetative barriers. The soil surface is stable and intact. Sub-surface soil layers are non-restrictive to water movement and root penetration. These soils are susceptible to wind and water erosion where vegetative cover is inadequate. Channel cutting, deposition, and removals may occur adjacent to streams. The total annual production ranges from 3500 to 4500 pounds of air dry vegetation per acre. Production is often affected by flooding events on these sites.

Dominant plant species

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

Figure 7. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 3425 | 3760 | 4090 |

| Shrub/Vine | 0 | 100 | 205 |

| Forb | 75 | 140 | 205 |

| Total | 3500 | 4000 | 4500 |

Figure 8. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). NE7507, Central Loess Plains, native - receiving water flow site. Warm-season dominant on sites receiving runoff water.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 27 | 29 | 15 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Community 1.2

Degraded Native Grass Community

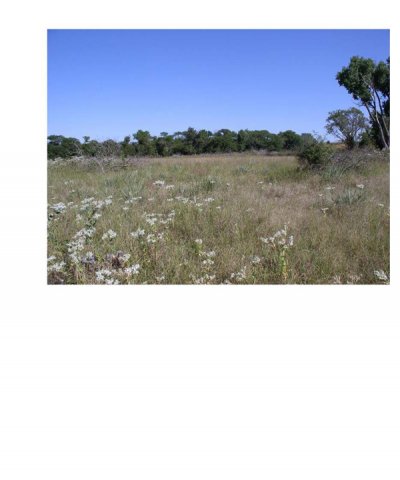

Figure 9. Degraded Native Grass Community

The major grasses include big bluestem and little bluestem. This is considered an at-risk community which shows a significant loss of yield in the production due to continuous season long grazing with inadequate recovery periods. Indiangrass has been significantly reduced in the plant community composition. Warm-season shortgrasses including blue grama, increase in the plant composition. The forb composition remains diverse. The potential is high for tree encroachment or regeneration. This plant community is less productive and the diversity of grasses is lower than the representative plant community and can be impacted by flooding on some sites. Pockets of trees occurred naturally on this site and it is very susceptible to woody encroachment. This site remains a sustainable plant community in regard to site/soil stability, watershed function, and biologic integrity. The total annual production ranges from 3000 to 4000 pounds of air dry vegetation per acre per year and will average 3500 pounds during an average year.

Dominant plant species

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

Community 1.3

Excessive Litter Community

The Excessive Litter Community Phase describes the response of the community to the removal of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire. As the duff layer deepens, infiltration of the precipitation is interrupted and evaporation increases significantly, simulating drought-like conditions.

Dominant plant species

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

Community 1.4

Ephemeral Forb Community

This community describes the flush of forbs that occurs in response to a major disturbance, or combination of disturbances. Growing season wildfire followed by hail, extreme prolonged drought, or extreme defoliation by herbivores are all examples of these disturbances. Potential forbs in this community include: marestail, cuman ragweed, cannabis, swamp verbena, hoary verbena, woolly plantain, Rocky Mountain beeplant, ironweed, snow-on-the-mountain, common evening primrose and shell leaf penstemon. The native warm-season grasses reestablish dominance within a few years of the event.

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

A shift from the Reference Community to the Degraded Native Grass Community occurs with continuous season-long grazing and inadequate recovery periods during the growing season. Repeated grazing of the growing point and grazing below recommended heights are other common reasons for a reduction in warm-season tallgrasses.

Pathway 1.1B

Community 1.1 to 1.3

Interruption of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire will result in conversion of this community to the Excessive Litter Community.

Pathway 1.1C

Community 1.1 to 1.4

A high-impact disturbance event, or combination of events causing excessive defoliation of the vegetation, i.e., a growing season wildfire followed by a significant hailstorm, prolonged intensive grazing event, or long-term drought, etc.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

A shift from the Degraded Native Grass Community toward the Reference Community can be achieved through prescribed grazing. Applying grazing pressure during the growth period of the undesirable cool-season grasses and allowing rest during the warm-season growth period favors the desired species. This grazing regime will enable the deeply rooted warm-season tallgrasses to outcompete the shallow-rooted grazing-evasive warm-season grasses and the cool-season grasses. Appropriately-timed prescribed fire will accelerate this process.

Conservation practices

| Access Control | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

Pathway 1.2B

Community 1.2 to 1.3

Interruption of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire will result in conversion of this community to the Excessive Litter Community.

Pathway 1.2C

Community 1.2 to 1.4

A high-impact disturbance event, or combination of events causing excessive defoliation of the vegetation, i.e., a growing season wildfire followed by a significant hailstorm, prolonged intensive grazing event, or long-term drought, etc.

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.1

Reintroduction of the natural processes of herbivory and fire will allow the vegetation to return to the previous community.

Pathway 1.3B

Community 1.3 to 1.2

Reintroduction of the natural processes of herbivory and fire will allow the vegetation to return to the previous community.

Pathway 1.3C

Community 1.3 to 1.4

A high-impact disturbance event, or combination of events causing excessive defoliation of the vegetation, i.e., a growing season wildfire followed by a significant hailstorm, prolonged intensive grazing event, or long-term drought, etc.

Pathway 1.4A

Community 1.4 to 1.1

Restoration occurs naturally once the disturbance event has subsided. Allowing growing season rest will accelerate the recovery.

Pathway 1.4B

Community 1.4 to 1.2

Restoration occurs naturally once the disturbance event has subsided. Allowing growing season rest will accelerate the recovery.

State 2

Native/Invaded Grass State

This state has been degraded from the Reference state and much of the native warm-season grass community has been replaced by less desirable plants. The loss of warm-season tall- and midgrasses has negatively impacted energy flow and nutrient cycling. Water infiltration and other hydrologic functions are reduced due to the root matting presence of sod-forming grasses and rapid runoff characteristics of the grazing-evasive plant communities. With the decline and loss of deeper penetrating root systems, soil structure and biological integrity are catastrophically degraded to the point that recovery is unlikely. Once this occurs, it is highly unlikely that grazing management alone will return the community to the Reference State. The Native Shortgrass/Invaded Grass and the Smooth Brome Communities are the components of the Native/Invaded Grass State.

Dominant plant species

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

-

smooth brome (Bromus inermis), grass

Community 2.1

Native Shortgrass/Invaded Grass Community

This plant community represents a shift from the Reference State across a major threshold. With continued grazing pressure, blue grama, Kentucky bluegrass, and other grazing adapted grasses will become the dominant plant species, with only trace remnants of the warm-season tall- and midgrasses such as big and little bluestem remaining. Continuous and heavy grazing pressure will maintain this plant community in a sod-bound condition, and forb richness and diversity will decrease. With the decline and loss of deeper penetrating root systems, a compacted layer may form in the soil profile below the shallow root systems of the more shallow rooted species. Grazing management practices that allow for adequate periods of recovery between grazing events will favor warm-season tall- and midgrasses. Appropriately timed prescribed fire accelerates the restoration process. Total annual production ranges from 2200 to 2800 pounds of air dry vegetation per acre.

Dominant plant species

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

Figure 10. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). NE7503, Central Loess Plains, warm season/cool season co-dominant. Native warm-season plant community encroached with cool-season grasses, MLRA 75.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 27 | 25 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

Community 2.2

Smooth Brome Community

This plant community contains predominately smooth brome but also contains native warm-season grass remnants. Production on smooth brome dominated plant communities are highly variable depending on the percent composition present and outside inputs such as fertilizer and weed control. Production can range from 2500 to 3000 pounds per acre with an average of 2750 pounds per acre in normal years on rangelands with a smooth brome component of 50 percent or more. Clipping or ocular estimates of production should be conducted to verify current annual production. Prescribed grazing, prescribed burning, or the use of herbicide treatments at critical time periods can reduce the smooth brome component in the plant community.

Dominant plant species

-

smooth brome (Bromus inermis), grass

Figure 11. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). NE7506, Central Loess Plains, cool season dominant, warm season remnants - receiving water flow site. Cool-season, smooth brome with native warm season remnants, sites receiving water runoff, MLRA 75.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 27 | 17 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 6 | 1 | 0 |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Introduced grass seeding, excessive warm-season grazing, inadequate growing season rest, multi season haying and nitrogen fertilizing in spring and/or fall are all management practices that will degrade CP 2.1 to CP 2.2. Prolonged drought will also cause this change to the plant community.

State 3

Sod-Busted State

This threshold is crossed as a result of mechanical disturbance to facilitate production agriculture. If farming operations are suspended, the site can be abandoned, which will result in the Natural Reclamation Community, or be re-seeded to a desired perennial forage mixture, which is described as the Reseeded Community. Permanent alterations of the soil community and the hydrological cycle make restoration to the original native Reference State extremely difficult, if not impossible. Formation of a compacted “plow pan” in the soil profile is likely.

Community 3.1

Reseeded Community

This plant community does not contain native remnants, and varies considerably depending on the seed mixture, the degree of soil erosion, the age of the stand, nitrogen fertilizer use, and past grazing management. Prescribed grazing with adequate recovery periods will be needed to maintain productivity and desirable species. Native range and seeded grasslands are ecologically different and should be managed separately. Factors such as functional group, species, stand density, and improved varieties all impact the production level and palatability of the seedings. Species diversity is often limited, and when grazed in conjunction with native rangelands, uneven forage utilization may occur. Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending on precipitation, management and grass species seeded. Single species stands of big bluestem, Indiangrass or switchgrass or well managed cool season grasses/legume plantings with improved varieties can yield 4000 to 5000 pounds per acre per year.

Community 3.2

Natural Reclamation Community

This plant community consists of annual and perennial weeds and less desirable grasses. These sites have been farmed and abandoned without being reseeded. Soil organic matter/carbon reserves are reduced, soil structure is changed, and a plow-pan or compacted layer can be formed which decreases water infiltration. Residual synthetic chemicals may remain from farming operations. In early successional stages, this community is not stable. Erosion is a concern. Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending on the succession stage of the plant community and any management applied to the system.

State 4

Invaded Woody State

Once the tree canopy cover reaches 15 percent with an average tree height exceeding 5 feet, the threshold is crossed to the Invaded Woody State. The primary coniferous interloper is eastern redcedar. Honeylocust and green ash number among the deciduous native trees, along with several exotic introduced species including Siberian elm. These woody species are encroaching due to lack of prescribed fire and other brush management practices. Typical ecological impacts are a loss of native warm season grasses, degraded forage productivity and reduced soil quality.

Dominant plant species

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

-

Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila), tree

Community 4.1

Invasive Woody Community

Shrubs and trees will establish readily on this site, and some sites could have been savannahs that contained pockets of trees and shrubs but have increased over time. Typical native trees include eastern cottonwood, green ash, hackberry, eastern redcedar, and honeylocust and various native shrubs. Siberian elm and eastern redcedar are invasive on these sites. When the Invasive Woody Community establishes, this forest or woodland community should be considered a non-commercial forest. Wood products derived from this community do not necessarily have commercial value.

Dominant plant species

-

Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila), tree

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

Figure 12. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). NE7505, Central Loess Plains, woody encroachment. Woody plant encroachment with warm- and cool-season grasses MLRA 75.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 3 | 8 | 12 | 20 | 25 | 14 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Heavy grazing without adequate recovery periods will cause this state to lose a significant proportion of warm-season tall- and midgrass species and cross a threshold to the Native/Invaded State. Water infiltration and other hydrologic functions will be reduced due to the root matting presence of sod-forming grasses. With the decline and loss of deeper penetrating root systems, soil structure and biological integrity are catastrophically degraded to the point that recovery is unlikely. The disruption to the plant community, the soils, and the hydrology of the system make restoration unlikely through grazing management alone.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The Reference State is significantly altered by mechanical tillage to allow the site to be placed into production agriculture. The disruption to the plant community, the soils, and the hydrology of the system make restoration to a true reference state unlikely.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

Disruption of the natural fire regime and the planting of invasive exotic and native woody species can cause this state to shift to the Invaded Woody State.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Development of a long-term management plan that includes an appropriate level of livestock grazing with adequate growing season rest for the desired species combined with strategically timed prescribed fire will return this state to the Reference State.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Access Control | |

| Integrated Pest Management (IPM) | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

The state is significantly altered by mechanical tillage to allow the site to be placed into production agriculture. The disruption to the plant community, the soil and the hydrology of the system make restoration unlikely.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

Disruption of the natural fire regime and the introduction of exotic species can cause this state to shift to the Invaded Woody State.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Disruption of the natural fire regime, and the planting of invasive exotic and native woody species causes a major shift in the vegetative community. The resulting impacts to the system cross the threshold into the Invaded Woody State.

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 1

Restoration from the Invaded Woody State can be achieved with brush management for woody plant control. If resprouting brush such as honeylocust or Siberian elm is present, stumps must be treated after mechanical removal. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments or periodic prescribed burning is required. If the site has a healthy warm season grass component, this community could quickly return to the previous state with the addition of prescribed grazing with adequate recovery periods.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Restoration pathway R4B

State 4 to 2

Restoration from the Invaded Woody State can be achieved with brush management for woody plant control. If resprouting brush such as honeylocust or Siberian elm is present, stumps must be treated after mechanical removal. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments or periodic prescribed burning is required. If the site has a healthy warm season grass component, this community could quickly return to the previous state with the addition of prescribed grazing with adequate recovery periods.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Restoration pathway R4C

State 4 to 3

Restoration from the Invaded Woody State can be achieved with brush management for woody plant control. If resprouting brush such as honeylocust or Siberian elm is present, stumps must be treated after mechanical removal. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments or periodic prescribed burning is required. If the site has a healthy warm season grass component, this community could quickly return to the previous state with the addition of prescribed grazing with adequate recovery periods.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Warm-Season Tallgrass | 1400–2000 | ||||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 1000–1600 | – | ||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 200–600 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 200–400 | – | ||

| 2 | Warm-Season Midgrass | 1000–1400 | ||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | 800–1200 | – | ||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 200–400 | – | ||

| composite dropseed | SPCOC2 | Sporobolus compositus var. compositus | 0–200 | – | ||

| 3 | Native Cool-season Grass | 125–400 | ||||

| western wheatgrass | PASM | Pascopyrum smithii | 80–400 | – | ||

| needle and thread | HECOC8 | Hesperostipa comata ssp. comata | 40–200 | – | ||

| porcupinegrass | HESP11 | Hesperostipa spartea | 0–200 | – | ||

| Scribner's rosette grass | DIOLS | Dichanthelium oligosanthes var. scribnerianum | 0–120 | – | ||

| Canada wildrye | ELCA4 | Elymus canadensis | 0–80 | – | ||

| prairie Junegrass | KOMA | Koeleria macrantha | 0–80 | – | ||

| 4 | Warm-Season Shortgrass | 125–400 | ||||

| blue grama | BOGR2 | Bouteloua gracilis | 0–200 | – | ||

| buffalograss | BODA2 | Bouteloua dactyloides | 0–200 | – | ||

| 5 | Grass-Likes | 40–80 | ||||

| Grass-like (not a true grass) | 2GL | Grass-like (not a true grass) | 0–80 | – | ||

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | 40–80 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 6 | Forbs | 60–400 | ||||

| Forb, perennial | 2FP | Forb, perennial | 40–80 | – | ||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 0–80 | – | ||

| white heath aster | SYER | Symphyotrichum ericoides | 0–80 | – | ||

| longbract spiderwort | TRBR | Tradescantia bracteata | 0–80 | – | ||

| purple prairie clover | DAPUA | Dalea purpurea var. arenicola | 0–80 | – | ||

| scarlet beeblossom | GACO5 | Gaura coccinea | 0–80 | – | ||

| hairy false goldenaster | HEVI4 | Heterotheca villosa | 0–80 | – | ||

| dotted blazing star | LIPU | Liatris punctata | 0–80 | – | ||

| Nuttall's sensitive-briar | MINU6 | Mimosa nuttallii | 0–80 | – | ||

| common evening primrose | OEBI | Oenothera biennis | 0–80 | – | ||

| silverleaf Indian breadroot | PEAR6 | Pediomelum argophyllum | 0–80 | – | ||

| large beardtongue | PEGR7 | Penstemon grandiflorus | 0–80 | – | ||

| slimflower scurfpea | PSTE5 | Psoralidium tenuiflorum | 0–80 | – | ||

| upright prairie coneflower | RACO3 | Ratibida columnifera | 0–80 | – | ||

| prairie groundsel | PAPL12 | Packera plattensis | 0–40 | – | ||

| Canada goldenrod | SOCA6 | Solidago canadensis | 0–40 | – | ||

| white sagebrush | ARLU | Artemisia ludoviciana | 0–40 | – | ||

| yellow sundrops | CASE12 | Calylophus serrulatus | 0–40 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 7 | Shrubs | 0–200 | ||||

| Shrub (>.5m) | 2SHRUB | Shrub (>.5m) | 0–120 | – | ||

| leadplant | AMCA6 | Amorpha canescens | 0–120 | – | ||

| prairie rose | ROAR3 | Rosa arkansana | 0–80 | – | ||

| western snowberry | SYOC | Symphoricarpos occidentalis | 0–40 | – | ||

| smooth sumac | RHGL | Rhus glabra | 0–40 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Grazing by domestic livestock is one of the major income-producing industries in the area. This site is well adapted to managed grazing by domestic livestock. Rangeland in this area may provide year-long forage for cattle, sheep, or horses. The predominance of herbaceous plants across all plant community phases best lends these sites to grazing but browsing livestock such as goats will utilize native and invasive forbs and brush. During the dormant period, the protein levels of the forage maybe lower than the minimum needed to meet livestock (primarily cattle and sheep) requirements and supplementation based on a reliable forage analysis may be necessary.

A grazing management strategy that protects the resource, maintains or improves rangeland health, and is consistent with management objectives will include appropriate stocking rates based on the carrying capacity of the land. In addition to useable forage, stocking rates should consider ecological condition of the land, trend of the site, grazing history, season of use, stock density, kind and class of livestock, forage quality, and harvest efficiency based on plant preference. It should also consider site accessibility and distance to drinking water. Average annual production must be measured or estimated to properly assess useable forage production and carrying capacity.

Carrying capacities and production estimates listed below are conservative estimates that should be used as guidelines in the initial stages of grazing lands planning. Often, the plant community does not entirely match any particular plant community (as described in the ecological site description). Because of this a resource inventory conducted as part of a field visit is recommended to document plant composition and production. More precise carrying capacity estimates can be calculated based on field verified production and species composition along with animal preference data for the type and class of animals and level of grazing management. With consultation of the land manager, more intensive grazing management may result in improved harvest efficiencies and increased carrying capacity.

Suggested stocking rates (carrying capacity) for cattle under continuous season-long grazing under normal growing conditions are listed below:

- Reference Community: 4000 lbs/acre production and 1.10 AUM/acre carrying capacity*

- Degraded Native Grass Community: 3500 lbs/acre production and 0.96 AUM/acre carrying capacity*

- Native Shortgrass/Invaded Grass Community: 2500 lbs/acre production and 0.68 AUM/acre carrying capacity*

- Smooth Brome Community (dryland, unfertilized, > 50 percent plant composition): 2750 lbs/acre and 0.75 AUM/acre carrying capacity*

-Seeded pasture (high managed/fertilized big bluestem or switchgrass single species plantings and smooth brome/legume plantings); 4500 lbs/acre production and 1.23 AUM/acre carrying capacity. Production for seeded pastures will increase with increased management and inputs such as nitrogen fertilizer, pasture plantings with improved varieties and rotational grazing.

* Continuous season-long grazing by cattle under average growing conditions, 25 percent harvest efficiency. Air dry forage requirements based on 3 percent of animal body weight, or 912 lbs/acre (air-dry weight) per Animal Unit Month (AUM). If distribution problems occur, stocking rates must be reduced to maintain plant health and vigor.

If excessive defoliation or grazing distribution problems occur, reduced stocking rates are needed to maintain plant health and vigor. Year-to-year and season-to-season fluctuations in forage production are expected due to weather conditions. To avoid overuse of forage plants when conditions are unfavorable to forage production, timely adjustments to livestock number or in the length of grazing periods are needed.

WILDLIFE INTERPRETATIONS:

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 75 lies primarily within the loess mixed-grass prairie ecosystem mixed with tallgrass prairie in lower areas. Prior to European settlement, this area consisted of diverse grassland habitats interspersed with varying densities of depressional wetlands and limited woody riparian corridors. These habitats provided critical life cycle components for the grassland birds, prairie dogs and herds of roaming bison, elk, and pronghorn that historically occupied this landscape. Diverse populations of small mammals and insects provided a bountiful prey base for raptors and omnivores such as coyotes, foxes, raccoons and opossums. Bobcats, wolves, and mountain lions occupied the apex predator niche. In addition, a wide variety of reptiles and amphibians thrived in this landscape.

The loess mixed-grass prairie was a disturbance-driven ecosystem with fire, herbivory and climate functioning as the primary disturbances. Following European settlement, elimination of fire, widespread conversion to cropland, and other sources of habitat fragmentation significantly altered the appearance and functionality of the entire ecosystem. The reduced stability of the system is reflected by major changes in the composition and abundance of the native flora and fauna. Introduced and invading species further degrade the ecological integrity of the plant and animal communities.

Bison and prairie dogs were historically keystone species but free-roaming bison herds and nearly all prairie dogs have been extirpated. The loss of bison and fire as ecological drivers greatly influenced the character of the remaining native grasslands and the habitats that they provide. In addition to free-ranging bison, extirpated species include pronghorn, wolves and swift fox.

Fragmentation has reduced habitat quality for numerous area-sensitive species, as highlighted by the decline of the greater prairie chicken. Many grassland nesting bird populations such as dickcissel and Henslow's sparrow are also declining.

Historically, an ecological mosaic of Loamy Upland, Closed Upland Depression, Loamy Lowland, and Loamy Overflow sites, provided habitat for species requiring unfragmented grasslands. Important habitat features and components found commonly or exclusively on modern day remnants include upland nesting habitat for grassland birds and game birds; nesting and escape cover for waterfowl; forbs and insects for brood rearing habitat; and a forage source for small and large herbivores. Within MLRA 75, remaining Loamy Lowland ecological sites provide grassland cover with an associated forb and limited shrub component.

In this fragmented landscape, native grassland bird populations face increasing competition from the opportunistic European starlings and house sparrows and are subject to nest parasitism from brown-headed cowbirds. Tree encroachment creates habitat that favors generalist species such as American robin and mourning dove, and provides perches for raptors, increasing the predation mortality. Introduced and invasive plant species such as smooth brome, reed canarygrass, Kentucky bluegrass, nodding plumeless thistle (musk thistle), and Canada thistle further degrade the biological integrity of many of these remnant prairies.

1. REFERENCE STATE: The predominance of tall and mid statured grasses plus a high diversity of forbs and shrubs in this community makes it ideal for grazers and mixed-feeders. Pollinating insects play a large role in maintaining the forb community and provide a food source for grassland birds and other grassland dependent species. The vegetative structural diversity provides habitat for reptiles, amphibians, and a wide array of native and introduced bird species including Henslow's sparrow, western meadowlark, northern bobwhite, and ringneck pheasants. The abundant prey base supports populations of Swainson’s hawk, burrowing, short-eared and great horned owls and other grassland raptors. Western meadowlark and American crow overwinter in this habitat.

The diversity of grasses, forbs and shrubs provide high nutrition levels for small and large herbivores including moles, mice, ground squirrels, white-tailed jackrabbit, and white-tailed deer. The structure of this plant community provides suitable thermal, protective and escape cover for small herbivores and grassland birds. Many wide-ranging predators utilize this plant community including coyote, badger, red fox and least and long-tailed weasels.

As the plant community degrades to more midgrasses and fewer tallgrasses, less winter and escape cover are provided. It also provides less cover for predators. As the plant community shifts from warm-season tallgrasses to midgrasses, it favors grassland birds that prefer shorter vegetation. This structural community provides better habitat for greater prairie chicken, lark bunting, and lark sparrow populations. Habitat in plant community 1.3 is much the same as 1.2 but provides less winter protection because of the reduced plant height and cover.

2. NATIVE/INVADED STATE: Although the amount of Kentucky bluegrass in this plant community varies, the generally lower structure height favors the suite of grassland birds that prefer more visual space. Increased dominance by Kentucky bluegrass with lower plant diversity provides less habitat for ringneck pheasant, northern bobwhite and mixed-feeders, such as whitetail deer and small mammals. Insect populations are somewhat reduced but still play a large role in maintaining the forb community and provide a moderate forage supply for grassland birds and other species. The reduced stature of this plant community still provides suitable thermal, protective and escape cover for small herbivores and grassland birds.

3. SODBUSTED STATE: Natural regeneration; As opportunistic disturbance oriented species, Kentucky bluegrass and smooth brome have become the prevalent grass species. The forb component exhibits lower diversity than the reference state and shifts towards increaser/ introduced forbs including sweetclover, western yarrow, Cuman ragweed, Missouri goldenrod, hoary verbena, and Ironweed. Pollinator insect populations are still present but experience a shift to generalist species.

Savannah sparrow, American robin, Western meadowlark are common birds that take advantage of the structure and composition of this plant community. The shorter stature of this plant community provides habitat for killdeer, horned lark, black-tailed jackrabbit (better suited to this plant community than white-tailed jackrabbit), and thirteen-lined ground squirrel. Prey populations are reduced and are more vulnerable to predation by raptors and mammalian predators. Burrowing owls may be associated with Richardson’s ground squirrel or other mammal burrows. The short stature of this plant community does not provide suitable thermal/protective cover and escape cover.

4. INVADED WOODY STATE:

The Mixed Woody Community provides habitat niches for white-tailed deer, wild turkey, raccoon, and Cooper’s, and sharp-shinned hawk among other species. Birds that are habitat generalists, such as the Bell’s Vireo, common yellowthroat, eastern kingbird, mourning dove, American goldfinch, northern bobwhite, field sparrow, solitary vireo, and pigmy nuthatch use woody cover for nesting, food, and breeding habitats. While a woody component of the grassland provides specific short-term habitats for some species, an expansive forest component is very detrimental to grassland wildlife species diversity and abundance overall.

Hydrological functions

Water is the principal factor limiting forage production on this site. This site is dominated by soils in hydrologic group B. Infiltration rate is moderate to moderately slow. Runoff potential for this site varies from very low to medium, depending on slope and ground cover. In many cases, areas with greater than 75 percent ground cover have the greatest potential for high infiltration and lower runoff. An example of an exception would be where rhizomatous grasses form a strong sod and dominate the site. Areas where ground cover is less than 50 percent have the greatest potential to have reduced infiltration and higher runoff (refer to Section 4, NRCS National Engineering Handbook for runoff quantities and hydrologic curves).

Recreational uses

This site provides hunting for upland game species along with hiking, photography, bird watching and other opportunities. The wide varieties of plants which bloom from spring until fall have an aesthetic value that appeals to visitors.

Wood products

Local or individual firewood can be utilized from this site. Eastern redcedar pulpwood can be utilized for veneer and/or cedar furniture. Cottonwood can be harvested for pallets.

Other products

None of significance.

Other information

Other Information

Annual reviews of the Project Plan are to be conducted by the Ecological Site Technical Team. The project plan is ES R075XY068NE- MLRA 75

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented here has been derived from NRCS clipping data and other inventory data. Field observations from range trained personnel were also used. Those involved in developing this site include Mike Kucera State Resource Conservationist, Mitch Faulkner, Rangeland Management Specialist, Nebraska; Dana Larsen, State Rangeland Management Specialist, Nebraska; Chuck Markley, Resource Soil Scientist, Nebraska; Mark Willoughby, Resource Soil Scientist, Nebraska; Doug Garrison, Dan Shurtliff and Mike Kucera completed the initial soils correlation and provided some of the photos. The positions listed were those held by the individuals at the time the original ESD was written.

Other references

High Plains Regional Climate Center, University of Nebraska. (http://hpcc.unl.edu, accessed 12/05/16)

Johnsgaard, P.A. 2001. “The Nature of Nebraska.” University of Nebraska Press.

LaGrange, T.G. 2015. Final Report submitted to EPA for the project entitled: Nebraska’s Wetland Condition Assessment: An Intensification Study in Support of the 2011 National Survey (CD# 97714601), and the related project entitled: Nebraska's Supplemental Clean Water Act §106 Funds, as Related to Participation in National Wetland Condition Assessment (I – 97726201). Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln.

Muhs, Daniel R., E. Bettis III, J. Aleinikoff, J. McGeehin, J. Beann, G. Skipp, B. Marshall, H. Roberts, W. Johnson, and R. Benton.

"Origin and paleoclimatic significance of late Quaternary loess in Nebraska: Evidence from stratigraphy, chronology, sedimentology, and geochemistry" (2008). USGS Staff -- Published Research. Paper 162. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/162 Accessed 12/05/16.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. NRCS National Ecological Site Handbook. January, 2014.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. NRCS National Engineering Handbook, Section 4. August, 2011.

Personal communications with professional ecologists and wildlife experts.

Rolfsmeier, S.B. and G. Steinauer. 2010. "Terrestrial Ecological Systems and Natural Communities of Nebraska", (version IV)

Nebraska Natural Heritage Program.

USDA, NRCS. National Water and Climate Center, Portland, OR. http://wcc.nrcs.usda.gov Accessed 12/05/16.

USDA, NRCS.1997. National Range and Pasture Handbook.

USDA, NRCS. National Soil Information System, Information Technology Center, Fort Collins, CO. http://nasis.nrcs.usda.gov Accessed 12/05/16.

USDA, NRCS. 2002. The PLANTS Database, Version 3.5 http://plants.usda.gov Accessed 12/05/16. National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA.

USDA, NRCS Soil Surveys from Gosper, Phelps, Kearney, Adams, Hamilton, Polk, York, Butler, Seward, Saline, Fillmore, Clay, Franklin, Webster, Nuckolls, Thayer and Jefferson counties in Nebraska, and Republic and Washington counties in Kansas.

Contributors

Nadine Bishop

Mike Kucera

Dana Larsen

Doug Garrison

Doug Whisenhunt

Approval

Suzanne Mayne-Kinney, 4/17/2025

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) |

Version V Authors: Jeff Nichols, Nadine Bishop Original Authors: Pat Broyles, Mike Kucera, Dana Larsen, Doug Whisenhunt |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | Kristin Dickinson, Acting State Rangeland Management Specialist, kristin.dickinson@usda.gov |

| Date | 11/30/2024 |

| Approved by | Suzanne Mayne-Kinney |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. Rills are not expected on this site. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

None. Rills are not expected on this site. Water will flow across the site during intense rainstorms, but water flow is sheet-like rather than concentrated into water flow patterns. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

None. Pedestals and terracettes are not expected to occur on this site. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Bare ground is 5 percent or less. Bare ground is exposed mineral soil that is not covered by vegetation (basal and/or foliar canopy), litter, standing dead vegetation, gravel/rock, and visible biological crust (e.g., lichen, mosses, algae). -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

None. Gullies are not expected on this site. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. Wind scoured and/or depositional areas are not expected on this site. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Fine litter will move after average to high rainfall events. Litter does not typically travel far (less than 12 inches or 30cm) and is trapped in small bunches by the extensive vegetative cover. Litter movement may be fairly extensive after high-intensity storms. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

): A-horizon is typically 7 inches (18 cm) thick. Soil color is grayish brown (10YR 5/2) when dry and very dark grayish brown (10YR 3/2) when moist. Soil structure is weak, medium granular; slightly hard and very friable. See Official Soils Descriptions for additional details. The major soil series correlated to this site is Hobbs. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

A-horizon is typically 7 inches (18 cm) thick. Soil color is grayish brown (10YR 5/2) when dry and very dark grayish brown (10YR 32) when moist. Soil structure is weak, medium granular; slightly hard and very friable. See Official Soils Descriptions for additional details. The major soil series correlated to this site is Hobbs. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

Plant community composition of 80 to 90 percent grasses and grass-likes, 2 to 5 percent forbs, and 0 to 5 percent shrubs will optimize infiltration on the site. The grass and grass-like portion is composed of perennial, native, warm-season, tall, mid-, and short grasses, perennial, native, cool-season grasses (3-10%), and grass-likes -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None. No compaction layers are expected to occur on this site. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Phase 1.1 -

1. Native, perennial, warm-season, tallgrass – 1400-2000 #/ac- 35-50%, (1 species min.): big bluestem, Indiangrass, switchgrass; 2. Native perennial, warm-season, mid-grasses– 1000-1400 #/ac - 25-35% (2species min.): little bluestem, sideoats grama, composite dropseed

Phase 1.2 -

1. Native, perennial, warm-season tallgrass: big bluestem, Indiangrass, switchgrass.

Phase 1.3 -

1. Native, perennial, warm-season tallgrass: big bluestem, Indiangrass, switchgrass.Sub-dominant:

Phase 1.2 -

1. Native, perennial, warm-season midgrass: little bluestem, sideoats grama, composite dropseed; 2. Native, perennial, warm-season shortgrass: blue Grama, buffalograss.

Phase 1.3 -

1. Native, perennial, warm-season midgrass: little bluestem, sideoats grama, composite dropseed; 2. Native, perennial, cool-season grasses: western wheatgrass, Canada wildrye, green needlegrass, needle and thread, Scribner’s rosettegrass, porcupine grass, prairie June grass.Other:

Minor - Phase 1.1 -

1. Native, perennial, cool season grasses– 125-400#/ac - 3-10%: western wheatgrass, Canada wildrye, green needlegrass, needle and thread, Scribner’s rosettegrass, porcupine grass, prairie June grass; 2. Native, perennial, warm-season, short grasses –125-400 #/ac - 3- 10%: blue grama, buffalograss; 3.Native forbs (perennial and annual) - 60-400 #/ac -2-10%: Species vary from location to location; 4Shrubs – 0-200 #/ac - 0-5%: leadplant, prairie rose, smooth sumac, western snowberry, other shrubs

Minor - Phase 1.2 -

1. Native, perennial, cool-season grasses: western wheatgrass, Canada wildrye, green needlegrass, needle and thread, Scribner’s rosettegrass, porcupine grass, prairie June grass; 2. Grass-likes: sedges and other grass-likes; 3. Native forbs (perennial and annual): species present will vary from location to location. 4. Shrubs: leadplant, prairie rose, smooth sumac, western snowberry, other shrubs.

Minor - Phase 1.3 -

1. Native, perennial, warm-season shortgrass: blue Grama, buffalograss; 2. Grass-likes: sedges and other grass-likes; 3. Native forbs (perennial and annual): species present will vary from location to location;4. Shrubs: leadplant, prairie rose, smooth sumac, western snowberry, other shrubs.

Trace - Phase 1.1 -

1. Grass-likes - 40-80 #/ac -1-2%: Sedges and other grass-likesAdditional:

The Reference Community (1.1) includes seven F/S Groups. These groups in order of abundance are native, perennial, warm-season tallgrass; native perennial, warm-season, midgrass; native, perennial, cool season grass; native, perennial, warm-season, shortgrass; native forbs (perennial and annual); shrubs; and grass-likes. The Degraded Native Grass Community (1.2) also includes seven F/S groups. These groups in order of abundance are native, perennial, warm-season, tallgrass; native perennial, warm-season, midgrass; native, perennial, warm-season shortgrass; native, perennial, cool season grass; grass-likes; forbs, and shrubs. The Excessive Litter Community (1.3) also includes seven F/S groups. These groups in order of abundance are native, perennial, warm-season, tallgrass; native perennial, warm-season, midgrass; native, perennial, cool season grass; native, perennial, warm-season shortgrass; grass-likes; forbs, and shrubs. -

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

A few (less than 3 percent) dead centers may occur in bunchgrasses. Shrubs may show some dead branches (less than 5 percent) as plants age. Plant mortality may increase to 10 to 15 percent following a multi-year drought, wildfire, prolonged flooding, or a combination of events. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Plant litter cover is evenly distributed throughout the site and is expected to be 50 to 70 percent and at a depth of 0.25 to 0.5 inches (0.65 to 1.3 cm). Kentucky bluegrass excessive litter can negatively impact the functionality of this site. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

Production is shown in air-dry values. The Representative Value (RV) = 4,000 pounds per acre. Low production years = 3,500 pounds per acre. High production years = 4,500 pounds per acre. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

No non-native invasive species are present. Silver bluestem, eastern redcedar, honey locust, common mullein, annual brome grasses are known invasives that have the potential to be dominant or co-dominant on the site. Consult the state noxious weed and state watch lists for potential invasive species on each ecological site. NOTE: Invasive plants (for the purposes of the IIRH protocol) are plant species that are typically not found on the ecological site or should only be in trace or minor categories under the natural disturbance regime and have the potential to become a dominant or codominant species on the site if their establishment and growth are not actively controlled by natural disturbances or management interventions. Species listed characterize degraded states AND have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

perennial species exhibit high vigor relative to climatic conditions. Perennial grasses should have vigorous rhizomes or tillers; vegetative and reproductive structures are not stunted. All perennial species should be capable of reproducing annually.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.