Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R079XY133KS

Wet Subirrigated

Last updated: 9/21/2018

Accessed: 02/27/2026

General information

Approved. An approved ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model, enough information to identify the ecological site, and full documentation for all ecosystem states contained in the state and transition model.

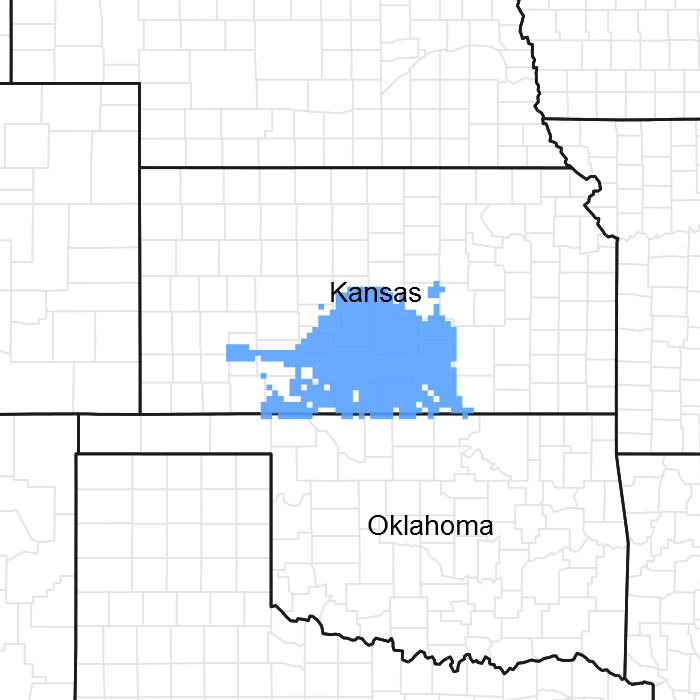

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 079X–Great Bend Sand Plains

MLRA 79 is located entirely in Kansas. It makes up about 7,405 square miles (19,185 square kilometers). Great Bend, Hutchinson, and Wichita are in this MLRA. U.S. Highways 50, 54, and 56 cross the area. The western part of McConnell Air Force Base and the Quivira National Wildlife Refuge are in this area.

Following are the various kinds of land use in this MLRA: Cropland-private, 67%; Grassland-private, 23%; Federal, 1%; Forest-private, 1%; Urban development-private, 5%; Water-private, 1%; Other-private, 2%.

Nearly all of this area is in farms or ranches. Most of the area is cropland. Cash-grain farming is the principal enterprise. Hard winter wheat is the major crop, but grain sorghum and alfalfa also are grown. The grassland in the area consists of sandy soils and steeply sloping areas. It supports native grasses grazed by beef cattle.

The major soil resource concerns are wind erosion, water erosion, maintenance of the content of organic matter in the soils, and soil moisture management. The major management

concerns on grassland are plant health and vigor, and control of noxious and invasive weeds.

Conservation practices on cropland generally include high residue crops in the cropping system; systems of crop residue management, such as no-till and strip-till systems; conservation crop rotations; wind stripcropping; and nutrient and pest management. Conservation practices on rangeland generally include brush management, prescribed burning, control of noxious weeds, pest management, watering facilities, and proper grazing use.

Classification relationships

Major land resource area (MLRA): 079-Great Bend Sand Plains

Ecological site concept

The Wet Subirrigated ecological site is characterized by poorly drained soils that have a seasonal or perennial high water table within two feet from the surface that usually results in some ponding or flooding on site. This site is located on floodplains and interdunes. The Wet Subirrigated site occurs on level to nearly level eolian and alluvial lands, usually adjacent to major streams.

Associated sites

| R079XY132KS |

Subirrigated This site occurs adjacent to and in conjunction with the Wet Subirrigated ecological site. The Subirrigated ecological site is characterized by somewhat poorly drained soils that have a seasonal or perennial high water table greater than 2 feet and less than 6 feet from the surface. This site is located on floodplains and interdunes. The Subirrigated site occurs on level to nearly level eolian and alluvial lands usually adjacent to major streams. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

Not specified |

Physiographic features

Most of this area is in the Plains Border Section of the Great Plains Province of the Interior Plains. The eastern third is in the Osage Plains Section of the Central Lowland Province of the Interior Plains. The undulating to rolling plains in this area generally have narrow valleys, but broad flood plains and terraces are along the Arkansas River and its larger tributaries. The elevation ranges from 1,650 to 2,600 feet (505 to 795 meters), increasing from east to west.

The extent of the major Hydrologic Unit Areas (identified by four-digit numbers) that make up this MLRA is as follows: Middle Arkansas (1103), 82 percent, and Arkansas-Keystone

(1106), 18 percent. The Arkansas River bisects the northern part of this MLRA, and the Ninnescah River crosses the southern part. In this MLRA, Rattlesnake Creek flows north and the Little Arkansas River flows south into the Arkansas River.

The Wet Subirrigated ecological site consists of deep to very deep, poorly drained soils. These soils formed from alluvium or eolian deposits over alluvium. This site occurs on floodplains and depressions on interdunes. Runoff is very slow and permeability is rapid.

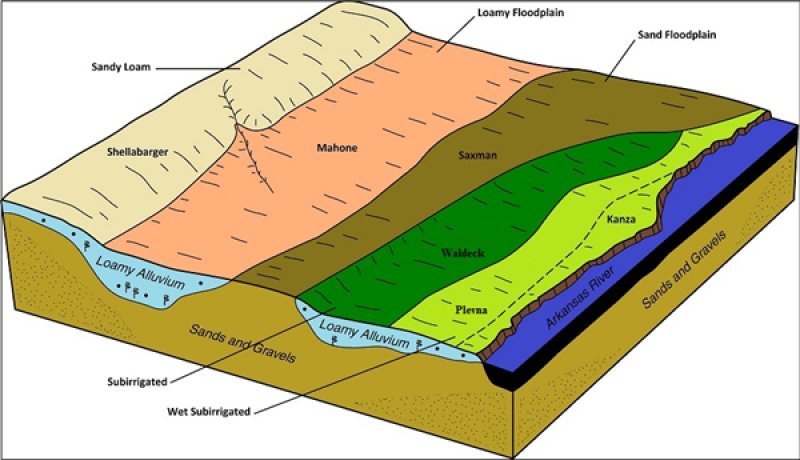

Figure 2. MLRA 79 ESD block diagram.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Flood plain

(2) Interdune (3) Depression |

|---|---|

| Flooding duration | Long (7 to 30 days) |

| Flooding frequency | None to frequent |

| Ponding duration | Long (7 to 30 days) |

| Ponding frequency | None to frequent |

| Elevation | 1,650 – 2,600 ft |

| Slope | 2% |

| Ponding depth | 12 in |

| Water table depth | 2 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The average annual precipitation in MLRA 79 is 25 to 33 inches (635 to 840 millimeters). Most of the rainfall occurs as high-intensity, convective thunderstorms during the growing season. The maximum precipitation occurs from the middle of spring to early in autumn. The annual snowfall ranges from about 14 inches (35 centimeters) in the southern part of the area to 20 inches (50 centimeters) in the northern part. The average annual temperature is 55 to 57 degrees F (13 to 14 degrees C). The freeze-free period averages 197 days, increasing in length from northwest to southeast.

Precipitation is usually evenly distributed throughout the year with the exception of November through February as being the driest months and May and June as being the wettest months. Summer precipitation occurs during intense summer thunderstorms.

The following weather data originated from weather stations chosen across the geographical extent of the ecological site, and will likely vary from the data for the entire MLRA. The climate data derives from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) National Water and Climate Center. The dataset is from 1981-2010.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 179 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 197 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 31 in |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) WELLINGTON [USC00148670], Wellington, KS

-

(2) GREENSBURG [USC00143239], Greensburg, KS

-

(3) KINGMAN [USC00144313], Kingman, KS

-

(4) STERLING [USC00147796], Sterling, KS

-

(5) NORWICH [USC00145870], Norwich, KS

-

(6) PRATT [USC00146549], Pratt, KS

-

(7) HUDSON [USC00143847], Hudson, KS

-

(8) HUTCHINSON [USC00143929], Hutchinson, KS

-

(9) HUTCHINSON 10 SW [USC00143930], Hutchinson, KS

-

(10) KINSLEY 2E [USC00144333], Kinsley, KS

-

(11) WICHITA [USW00003928], Wichita, KS

Influencing water features

Influencing water features on this ecological site include a seasonal or perennial water table that occurs less than 2 feet from the surface. This water table influences the kinds and amounts of vegetation, and the management of the site, making it distinctive from other ecological sites.

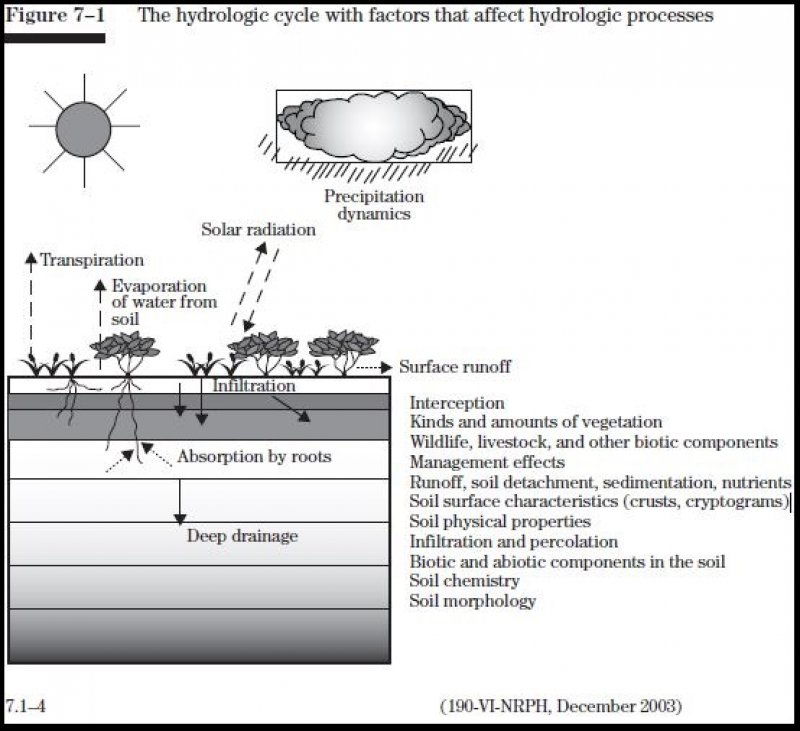

Figure 7. Fig.7-1 from National Range and Pasture Handbook.

Soil features

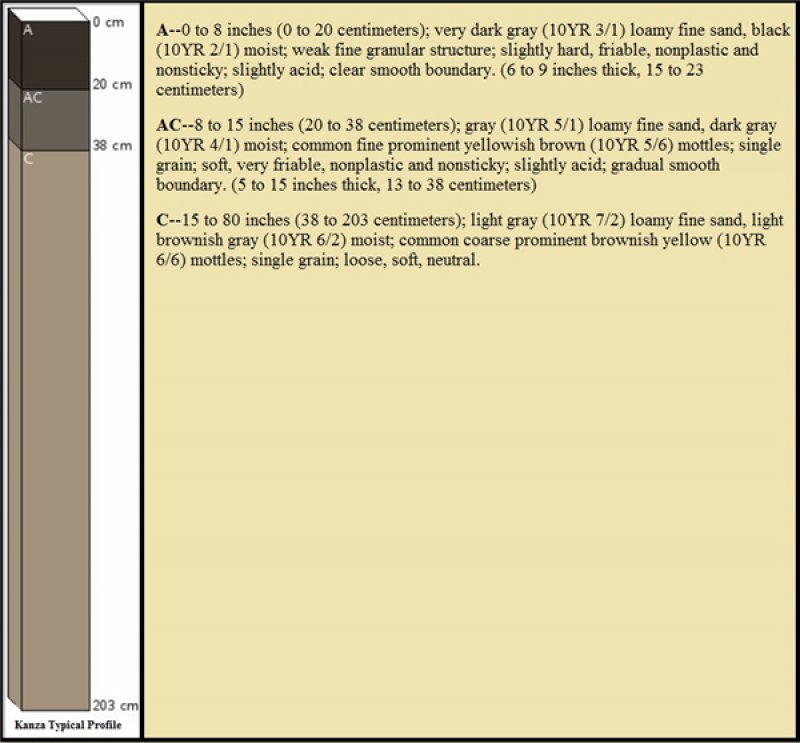

Soils on this site are characterized as deep and loamy with a seasonal or perennial water table that occurs within 2 feet from the surface and usually has flooding or ponding occurring on the site. These soils occur on depressions on interdunes or flood plains, and formed in alluvium or eolian deposits over alluvium. Surface soils and subsoils will range from sands to silty clay loams. Permeability ranges from very slow to rapid.

The major soils common to this site include Kanza, Plevna, Kingman, Carway, Ninnescah, and Carbika.

Figure 8. Kanza typical soil profile.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Fine sandy loam (2) Loamy fine sand (3) Silt loam |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Poorly drained to somewhat poorly drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow to rapid |

| Soil depth | 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

3.6 – 10.2 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

14% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

4 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

1 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

5.1 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

14% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

This is a dynamic plant community due to the complex interaction of many ecological processes. The vegetation evolved on soils with high water tables, under a diverse and fluctuating climate, while grazed by herds of large herbivores and subjected periodically to intense wildfires.

The deep soils representative of this site generally occur in dunes or broad, nearly level floodplains, usually adjacent to rivers or streams. The site may also occur along narrow drainways or on areas containing perennial seeps or springs. The major influence for plant adaptation and growth is the presence of a permanent water table that generally varies to a depth of less than two feet. Occasional flooding may occur in some locations from stream overflow. The plants that evolved and dominated the original plant community were adapted to these soil conditions and benefited from the dependable source of moisture. The available water capacity of this site is high. The Wet Subirrigated ecological site can be very productive. The wet condition tends to nullify the effect of precipitation.

The plant community developed with occasional fires as an important element of the ecological processes. Historically fires were usually started by lightning during spring and early summer months when thunderstorms were most prevalent. It is also recognized that early Native Americans often used fire to attract herds of migratory herbivores, especially bison. These intentional fires probably occurred more frequently than naturally caused fires, even on an annual basis. Because all of the dominant tallgrasses were rhizomatous and soil conditions were usually moist, these plants could survive the ravages of even intense wildfires. This gave them a competitive advantage in the plant community. In contrast, most trees and shrubs were suppressed by fire and occurred only sparsely on protected areas, generally along stream banks.

Grazing history had a major impact on the dynamics of the site. The vegetative community developed under a grazing regime that consisted primarily of periodic grazing by large herds of bison. As the herds moved through an area, grazing was probably intense but of short duration. As they moved on to other areas, the vegetation was afforded a period of recovery. Other grazing and feeding animals such as deer, rabbits, insects, and numerous burrowing rodents had secondary influences on plant community development.

Variations in climate had only minimal impact upon the development of the plant community due to the ever-present water table. The deeper-rooted major grasses would continue to benefit from the water table even during periods of extended drought. Occasional flooding that resulted from intense thunderstorms was usually brief in duration and the resulting inundation only temporarily affected major plants. Several of the tall grasses, especially eastern gamagrass, prairie cordgrass, and common reedgrass had extensive rhizomes which enabled them to endure and recover from occasional siltation deposited during flood events.

Typically, growth of warm-season grasses on this site begins during the period of April 25 to May 10 and continues until mid-September. As a general rule, 75 percent of total production is completed by mid-July. This varies only slightly from year to year. Cool-season grasses, sedges, and rushes generally have two primary growth periods, one in the fall (September and October) and again in the spring (April, May, and June).

As utilization of the area for production of domestic livestock replaced that of roaming bison herds, the ecological dynamics of the site were altered. In many areas the plant community changed from its original composition. Fencing enabled continuous grazing that in many areas led to overgrazing and accelerated changes in the vegetation. Alterations in the plant community were usually in proportion to when grazing occurred as well as its intensity. The taller grasses and forbs palatable to bison were equally relished and selected by cattle and other domestic livestock. When repeatedly overgrazed, these grasses were weakened and gradually diminished in the plant community. They were replaced by the increase and spread of less palatable grasses and forbs. Where the history of overgrazing by domestic livestock was more intense, even the plants that initially increased were often replaced by even less desirable, and usually lower-producing plants.

The occurrence of wildfires and the impact that fire played in maintaining the plant community was diminished with the advent of roads and cultivated fields. Use of prescribed fire as a management tool, often not an option in modern communities, also diminished. The absence of fire has contributed to a gradual increase of tree species in many areas. In some locations trees have spread to the point they have become a major influence in the plant community.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Grassland State

The Grassland State defines the ecological potential and natural range of variability resulting from the natural disturbance regime of the Wet Subirrigated ecological site. This state is supported by empirical data, historical data, local expertise, and photographs. It is defined by a suite of native plant communities that are a result of periodic fire, drought, and grazing. These events are part of the natural disturbance regime and climatic process. The Reference Plant Community consists of warm-season tall and midgrasses, cool-season grasses, and forbs. The Annual Plant Community is made up primarily of annual grasses, sedges, and rushes.

Community 1.1

Reference Plant Community

The interpretive plant community for this site is the Reference Plant Community. This plant community represents the original plant community that existed prior to European settlement. The site is characterized as a grassland essentially free of trees and large shrubs. It is dominated by prairie cordgrass followed by eastern gamagrass, spikerush, alkali cordgrass, and reed canarygrass. These tallgrasses in combination with others will account for 90 percent of the total vegetation produced annually. Several species of sedges and rushes are present. The major forbs found interspersed throughout the grass sward are Cuman ragweed, Illinois bundleflower, Pennsylvania smartweed, Maximilian sunflower, wholeleaf rosinweed, and broadleaf cattail. These forbs account for 10% of the vegetation produced annually. Desert false indigo, common buttonbush, and roughleaf dogwood are shrubs that occur in sparse amounts over the site. Eastern cottonwood and black willow are trees that can inhabit this site. Eastern cottonwood may be found as isolated plants scattered over the site or it may form small groves. Black willow is generally located along drainageways. When adequately managed this is a stable, resilient, and very productive plant community . A prescribed grazing program that incorporates periods of deferment during the growing season perpetuates the more palatable tallgrasses and forb species. Due to the wetness of this site it is generally not managed for the production of native hay, sometimes referred to as prairie hay. Growth of warm-season grasses on this site typically begins during the period of April 25 to May 10 and continues until late September. As a general rule, 75 percent of total production is completed by mid-July. This varies only slightly from year to year depending on temperature and precipitation patterns. There are exceptions as big bluestem, eastern gamagrass, and prairie cordgrass will occasionally initiate spring growth as early as April 1 following mild winter temperatures. Also, it’s not unusual for other warm-season grasses such as Indiangrass to have some new leaf growth arising from basal buds in late October following moderate fall temperatures. Cool-season grasses, sedges, and rushes generally have two primary growth periods, one in the fall (September and October) and again in the spring (April, May, and June). Some growth may occur in winter months during periods of unseasonably warm temperatures (Indian summers).

Figure 9. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 6000 | 6300 | 6500 |

| Forb | 700 | 700 | 700 |

| Total | 6700 | 7000 | 7200 |

Community 1.2

Annual Plant Community

This plant community results from many years of overgrazing. The amount of tallgrasses has decreased significantly and the site is dominated by annual grasses, sedges, rushes, and forbs. Major grasses include barnyardgrass, annual bristlegrass, annual sedge, annual rush, and foxtail barley. Major forbs on the site include Cuman ragweed, Canada goldenrod, Missouri goldenrod, white sagebrush, Carruth’s sagewort, white heath aster, swamp smartweed, swamp milkweed, swamp verbena, annual marshelder, and annual ragweed. In some locations the Wet Subirrigated site supports an increasing amount of trees. Eastern cottonwood, black willow, peachleaf willow, American elm, eastern redcedar, and Russian olive are the major trees that could be found on the site. Both eastern redcedar and Russian olive were introduced to the area through shelterbelt and windbreak plantings. Trees usually will not comprise over ten percent of the total production. Remnant plants of big bluestem, Indiangrass, switchgrass, prairie cordgrass, eastern gamagrass, and Maximilian sunflower can be found scattered throughout the site. These plants are usually grazed repeatedly and maintained in a low state of vigor. They respond favorably to periods of rest from grazing during the growing season and often regain vigor in 1 to 2 years.

Pathway 1.1 to 1.2

Community 1.1 to 1.2

The following describes the mechanisms of change from Plant Community 1.1 to Plant Community 1.2. These mechanisms include management controlled by repetitive heavy use, no rest or recovery of the key forage species, no forage and animal balance for many extended grazing seasons. This type of management for periods longer than 10 years will shift functional and structural plant group dominance toward Plant Community 1.2.

Pathway 1.2 to 1.1

Community 1.2 to 1.1

The following describes the mechanisms of change from Plant Community 1.2 to Plant Community 1.1. Management (10-15 years) that includes adequate rest and recovery of the key forage species (prairie cordgrass, eastern gamagrass, big bluestem, Indiangrass, and switchgrass) within the Reference Plant Community. If woody species are present, prescription fires every 6-8 years will be necessary for their removal and/or maintenance.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 2

Woody State

This state is dominated by a shrub and/or tree plant community. The increase and spread of shrubs and trees results from an absence of fire. Woody plants can increase up to 34% from a lack of fire according to a study from 1937 to 1969, in contrast to a 1% increase on burned areas (Bragg and Hulbert, 1976). Periodic burning tends to hinder the establishment of most woody species and favors forbs and grasses. However, it should be pointed out that not all unburned areas have a woody plant invasion. Hydrologic function is affected by the amount of vegetative cover. Canopy interception loss can vary from 25.4% to 36.7% (Thurow and Hester, 1997). A small rainfall event is usually retained in the foliage and does not reach the litter layer at the base of the tree. Only when canopy storage is reached and exceeded does precipitation fall to the soil surface. Interception losses associated with the accumulation of leaves, twigs, and branches at the base of trees are considerably higher than losses associated with the canopy. The decomposed material retains approximately 40% of the water that is not retained in the canopy (Thurow and Hester, 1997). Soil properties affected include biological activity, infiltration rates, and soil fertility. Special planning will be necessary to assure that sufficient amounts of fine fuel are available to carry fires with enough intensity to control woody species. In some locations the use of chemicals as a brush management tool may be desirable to initiate and accelerate this transition. Birds, small mammals, and livestock are instrumental in the distribution of seed and accelerating the spread of most tree and shrubs common to this site. The speed of encroachment varies considerably and can occur on both grazed and non-grazed pastures. Many species of wildlife, especially bobwhite quail, turkey, and white-tailed deer benefit from the growth of trees and shrubs for both food and cover. When management for specific wildlife populations is desirable, these options should be considered in any brush management plan.

Community 2.1

Woody Community

Trees and shrubs dominate this plant community and may produce 40 to 50 percent of the total vegetation. Major trees include eastern cottonwood, black willow, peachleaf willow, American elm, Siberian elm, common hackberry, eastern redcedar, and Russian olive. More abundant shrubs could include roughleaf dogwood, coralberry, Great Plains false willow, desert false indigo, and common buttonbush. These woody plants spread in the absence of fire and may do so regardless of grazing management. However, not all unburned areas have a woody plant problem. Encroachment may occur on areas that have been overgrazed for years as well as where both grazing and fire have been excluded. The speed and method of encroachment varies considerably. Cottonwood and willow produce an abundance of seed that is distributed long distances by wind. Russian olive and eastern redcedar are spread by birds. Periodic burning tends to hinder the establishment of most of these woody species and favor forbs and grasses. Where woody plants have invaded overgrazed areas, understory vegetation is generally dominated by plants such as Texas bluegrass, Kentucky bluegrass, composite dropseed, marsh bristlegrass, chairmaker’s threesquare, sedges, white sagebrush, interior ironweed, and white heath aster. Where woody plants have encroached onto nonutilized areas, the understory consists largerly of big bluestem, Indiangrass, prairie cordgrass, Canada wildrye, chairmaker’s threesquare, sedges, prairie bundleflower, and Maximilian sunflower. Herbage production is significantly reduced because of tree and shrub competition. Grass yields vary from 30 to 40 percent of the total vegetative production. Forbs generally produce 5 to 10 percent of the total. Total annual production is variable and more data collection is necessary in order to display estimates. Usually a prescribed burning program, accompanied by prescribed grazing, will return the plant community to one dominated by grasses and forbs. Special planning will be necessary to assure that sufficient amounts of fine fuel are available to carry fires with enough intensity to control the woody species. In some locations use of chemicals or mechanical methods as a brush management tools may be necessary to initiate and accelerate this transition.

Transition 1 to 2

State 1 to 2

Changes from a Grassland State to a Woody State lead to changes in hydrologic function, forage production, dominant functional and structural groups, and wildlife habitat. Understory plants may be negatively affected by trees and shrubs by a reduction in light, soil moisture, and soil nutrients. Increases in tree and shrub density and size have the effects of reducing understory plant cover and productivity, with desirable forage grasses often being most severely reduced (Eddleman, 1983). As vegetation cover changes from grasses to trees, a greater proportion of precipitation is lost throughout interception and evaporation; therefore, less precipitation is available for producing herbaceous forage or for deep drainage or runoff (Thurow and Hester, 1997). Tree and shrub establishment becomes increasingly greater while fine fuel loads decrease. As trees and shrubs increase at levels of greater than 20 percent canopy cover, the processes and functions that allow the Woody State to become resilient are active and dominate over the processes and systems inherent of the Grassland State. Using prescribed fire as a standalone management tool is unsuccessful to eradicate the trees and shrubs due to a lack of fine fuel loads.

Restoration pathway 2 to 1

State 2 to 1

Restoration efforts will be costly, labor-intensive, and can take many years, if not decades, to return to a Grassland State. Once canopy levels reach greater than 20 percent, estimated cost to remove trees is very expensive and includes high energy inputs. The technologies needed in order to go from an invaded Woody State to a Grassland State include but are not limited to: prescribed burning—the use of fire as a tool to achieve a management objective on a predetermined area under conditions where the intensity and extent of the fire are controlled; brush management—manipulating woody plant cover to obtain desired quantities and types of woody cover and/or to reduce competition with herbaceous understory vegetation, in accordance with overall resource management objectives; and prescribed grazing—the controlled harvest of vegetation with grazing or browsing animals managed with the intent to achieve a specified objective. In addition to grazing at an intensity that will maintain enough cover to protect the soil and maintain or improve the quantity and quality of desirable vegetation. When a juniper tree is cut and removed, the soil structure and the associated high infiltration rate may be maintained for over a decade (Hester, 1996). This explains why the area near the dripline usually has substantially greater forage production for many years after the tree has been cut. It also explains why runoff will not necessarily dramatically increase once juniper is removed. Rather, the water continues to infiltrate at high rates into soils previously ameliorated by junipers, thereby increasing deep drainage potential. In rangeland, deep drainage amounts can be 16 percent of the total rainfall amount per year (Thurow and Hester, 1997).

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Grasses Dominant 90% | 3000–6300 | ||||

| prairie cordgrass | SPPE | Spartina pectinata | 1750–2500 | – | ||

| eastern gamagrass | TRDA3 | Tripsacum dactyloides | 300–630 | – | ||

| spikerush | ELEOC | Eleocharis | 250–630 | – | ||

| reed canarygrass | PHAR3 | Phalaris arundinacea | 150–315 | – | ||

| alkali cordgrass | SPGR | Spartina gracilis | 150–315 | – | ||

| chairmaker's bulrush | SCAM6 | Schoenoplectus americanus | 100–250 | – | ||

| shortbeak sedge | CABR10 | Carex brevior | 100–250 | – | ||

| clustered field sedge | CAPR5 | Carex praegracilis | 100–250 | – | ||

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | 100–250 | – | ||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 0–160 | – | ||

| composite dropseed | SPCO16 | Sporobolus compositus | 0–160 | – | ||

| western wheatgrass | PASM | Pascopyrum smithii | 0–160 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 0–160 | – | ||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 0–160 | – | ||

| Canada wildrye | ELCA4 | Elymus canadensis | 0–160 | – | ||

| Heller's rosette grass | DIOL | Dichanthelium oligosanthes | 0–80 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 2 | Forbs Minor 10% | 200–700 | ||||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 50–150 | – | ||

| Illinois bundleflower | DEIL | Desmanthus illinoensis | 50–150 | – | ||

| Maximilian sunflower | HEMA2 | Helianthus maximiliani | 50–150 | – | ||

| Pennsylvania smartweed | POPE2 | Polygonum pensylvanicum | 50–150 | – | ||

| wholeleaf rosinweed | SIIN2 | Silphium integrifolium | 50–150 | – | ||

| broadleaf cattail | TYLA | Typha latifolia | 0–100 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

The great plant diversity associated with this site, wetland inclusions, and the fact that it frequently occurs in riparian areas makes this site excellent wildlife habitat. It is characterized by scattered willow and cottonwood trees and occasional mottes of low brush which create a preferred habitat for white-tailed deer, wild turkey, bobwhite quail, pheasant, fox squirrel, and eastern cottontail. Furbearers such as mink, raccoon, skunk, and opossum are common as are predators such as the bobcat, coyote, and red fox. When in good to excellent condition, the site is especially valuable as winter cover for many of these same species.

A variety of birds are common to the site and include scissortailed flycatchers, eastern and western kingbirds, brown thrasher, mourning dove, and redwinged blackbird. Hawks and owls commonly use this habitat and bald eagles are occasional visitors. Waterfowl are commonly seen during their spring and fall migrations.

Some animals are important because of their threatened and endangered status and require special consideration. Please check the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks (KDWP) website at http://ksoutdoors.com/ for the most current listing for your county.

Grazing Interpretations

Calculating Safe Stocking Rates: Proper stocking rates should be incorporated into a grazing management strategy that protects the resource, maintains or improves rangeland health, and is consistent with management objectives. In addition to usable forage, safe stocking rates should consider ecological condition, trend of the site, past grazing use history, season of use, stock density, kind and class of livestock, forage digestibility, forage nutritional value, variation of harvest efficiency based on preference of plant species, and/or grazing system, and site grazeability factors (such as steep slopes, site inaccessibility, or distance to drinking water).

Often the current plant community does not entirely match any particular Community Phase as described in this Ecological Site Description. Because of this, a resource inventory is necessary to document plant composition and production. Proper interpretation of inventory data will permit the establishment of a safe initial stocking rate.

No two years have exactly the same weather conditions. For this reason, year-to-year and season-to-season fluctuations in forage production are to be expected on grazing lands. Livestock producers must make timely adjustments in the numbers of animals or in the length of grazing periods to avoid overuse of forage plants when production is unfavorable, and to make advantageous adjustments when forage supplies are above average.

Initial stocking rates should be improved through the use of vegetation monitoring and actual use records that include number and type of livestock, the timing and duration of grazing, and utilization levels. Actual use records over time will assist in making stocking rate adjustments based on the variability factors.

Average annual production must be measured or estimated to properly assess useable forage production and stocking rates.

Hydrological functions

These have a high water table which normally is less than 2 feet below the soil surface. Runoff potential for this site is negligible to low.

Following are the estimated withdrawals of freshwater by use in MLRA 79:

Public supply—surface water, 6.8%; ground water, 4.0% Livestock—surface water, 0.4%; ground water, 1.2% Irrigation—surface water, 0.7%; ground water, 80.6% Other—surface water, 2.0%; ground water, 4.3%.

The total withdrawals average 740 million gallons per day (2,800 million liters per day). About 90 percent is from ground water sources, and 10 percent is from surface water sources. The source of water for crops and pasture is the moderate, somewhat erratic precipitation. In the northern part of the area, the Arkansas River is a potential source of irrigation water, but it currently is little used for this purpose. The Ninnescah River is another potential source of surface water in the area. Deep sand in the High Plains or Ogallala aquifer yields an abundance of good-quality ground water. This aquifer provides water primarily for irrigation but also for domestic supply and livestock in rural areas and for industry and public supply in Wichita and in other towns or cities in the MLRA. The ground water in this aquifer has the lowest levels of total dissolved solids of any aquifer in Kansas, 340 parts per million (milligrams per liter).

Recreational uses

This site is very desirable for outdoor recreational pursuits because of its plant and wildlife diversity. Big game, white-tail deer and wild turkey are abundant and commonly hunted along with a wide variety of small game such as pheasant, quail, rabbits, squirrels, and raccoons. In addition, there are ample opportunities for bird watching, hiking, outdoor/wildlife photography, and a variety of other outdoor activities. A wide variety of plants bloom throughout the growing season and provide much aesthetic appeal to the landscape. Recreation can be a high value use, but the excessive wetness due to the prevalent high water table is a significant site consideration.

Wood products

None noted.

Other products

The presence of abundant soil moisture makes this site especially vulnerable to several invasive woody plant species such as Russian olive, multiflora rose, and saltcedar on more saline soils. An extra effort should be made to eradicate any known plantings of these three species near wet subirrigated sites. These species have been recognized as invasive and are no longer recommended for woody plantings. Extra care should also be taken in the planning and design of any woody plantings adjacent to or near this site. Only those woody species native to the area should be considered for plantings.

Other information

Site Development and Testing Plan

This site went through the approval process.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented here has been derived from NRCS clipping data, numerous ocular estimates, and other inventory data. Field observations from experienced range-trained personnel were used extensively to develop the Wet Subirrigated ecological site description.

This is a new site developed with guidance from the Subirrigated ecological site. Several soil series were taken out of the Subirrigated site and correlated to the Wet Subirrigated site.

Range Condition Guides and Technical Range Site Descriptions for Kansas, Wet-Land, USDA, Soil Conservation Service, March, 1967.

Other references

Brady, N. and R. Weil. 2008. The nature and properties of soils, 14th ed.

Bragg, T. and L. Hulbert. 1976. Woody plant invasion of unburned Kansas bluestem prairie. J. Range Management., 29:19-23.

Dyksteruis, E.J. 1958. Range conservation as based on sites and condition classes. J. Soil and Water Conserv. 13: 151-155.

Eddleman, L. 1983. Some ecological attributes of western juniper. P. 32-34 in Research in rangeland management. Agric. Exp. Stan. Oregon State Univ., Corvallis Spec. Rep. 682.

Hester, J.W. 1996. Influence of woody dominated rangelands on site hydrology and herbaceous production, Edwards Plateau, Texas. M.S. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

Holechek, Jerry, Rex Pieper, Carlton Herbel, Range Management: principles and practices.—5th ed.

Kuchler, A. A New Vegetation Map of Kansas. Ecology (1974) 55: pp. 586-604.

Launchbaugh, John, Clenton Owensby. Kansas Rangelands, Their Management Based on a Half Century of Research, and Bull. 622 Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station, October 1978.

Moore, R., J. Frye, J. Jewett, W. Lee, and H. O'Connor. 1951. The Kansas rock column. Univ. Kans. Pub., State Geol. Survey Kans. Bull. 89. 132p.

National Climatic Data Center. Weather data web site http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/. Available online. Accessed 04/05/2017.

National Range and Pasture Handbook, USDA-NRCS, Chapter 7, Rangeland and Pastureland Hydrology and Erosion.

Rangeland Cover Types of the United States, Society for Range Management, 1994.

Sauer. Carl, Grassland climax, fire, and man. 1950, J. Range Manage. 3: 16-21.

Soil Series—Official Series Descriptions, https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/osdname.asp. Available online. Accessed 04-05-2017.

Thurow, T. and J. Hester. 1997. How an increase or reduction in juniper cover alters rangeland hydrology, In: C.A. Taylor, Jr. (ed.). Proc. 1997 Juniper Symposium. Texas Agr. Exp. Sta. Tech. Rep. 97-1. San Angelo, TX: 4:9-22.

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service—Soil Surveys and Web Soil Survey. Available online. Accessed 04/05/2017.

USDA Handbook 296, LRR and MLRA of the U.S., the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin.

Waller, S., Moser, L. Reece. P., and Gates. 1985 G. Understanding Grass Growth.

Weaver, J. and F. Albertson, Deterioration of Midwestern Ranges, Ecology, Vol. 21, No. 2, April 1940, pp. 216-236.

Contributors

Chris Tecklenburg

Approval

David Kraft, 9/21/2018

Acknowledgments

The ecological site development process is a collaborative effort, conceptual in nature, dynamic, and is never considered complete. I thank all those who contributed to the development of this site. In advance, I thank those who would provide insight, comments, and questions about this ESD in the future.

Non-discrimination Statement

In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident.

Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available

in languages other than English.

To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at How to File a Program Discrimination Complaint and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by:

(1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights 1400 Independence Avenue, SW Washington, D.C. 20250-9410;

(2) fax: (202) 690-7442; or

(3) email: program.intake@usda.gov.

USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender.

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) |

Chris Tecklenburg original 02/21/2018 with assistance from Subirrigated rangeland health reference sheet originally created by David Kraft, John Henry, Doug Spencer, Dwayne Rice 2/2005. |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author |

Chris Tecklenburg chris.tecklenburg@ks.usda.gov |

| Date | 02/21/2018 |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

There is little, if any, evidence of soil deposition or erosion. Water generally flows evenly or ponds over the entire landscape. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

There is no evidence of pedestaled plants or terracettes on the site. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Less than 5% bare ground is found on this site. Cover can be defined as live plants, litter, rocks, moss, lichens, etc. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

None -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

There is no evidence of wind erosion creating bare areas or denuding vegetation. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Plant litter is distributed evenly throughout the site. During major flooding events this site slows water flow and captures litter and sediment. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Plant canopy is large enough to intercept the majority of raindrops. A soil fragment will not “melt” or lose its structure when immersed in water for 30 seconds. There is no evidence of pedestaled plants or terracettes. Soil stability scores will range from 5-6. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

From Kanza series description:

A--0 to 8 inches (0 to 20 centimeters); very dark gray (10YR 3/1) loamy fine sand, black (10YR 2/1) moist; weak fine granular structure; slightly hard, friable, nonplastic and nonsticky; slightly acid; clear smooth boundary. (6 to 9 inches thick, 15 to 23 centimeters)

AC--8 to 15 inches (20 to 38 centimeters); gray (10YR 5/1) loamy fine sand, dark gray (10YR 4/1) moist; common fine prominent yellowish brown (10YR 5/6) mottles; single grain; soft, very friable, nonplastic and nonsticky; slightly acid; gradual smooth boundary. (5 to 15 inches thick, 13 to 38 centimeters)

C--15 to 80 inches (38 to 203 centimeters); light gray (10YR 7/2) loamy fine sand, light brownish gray (10YR 6/2) moist; common coarse prominent brownish yellow (10YR 6/6) mottles; single grain; loose, soft, neutral.

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

There is no negative effect on water infiltration and/or runoff due to plant composition or distribution. Plant composition and distribution are adequate to prevent any rill formation and/or pedastalling. Interspacial distribution is consistent with expectation for the site. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

There is no evidence of compacted soil layers due to cultural practices. Soil structure is conducive to water movement and root penetration. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Grasses dominant 90%: prairie cordgrass 1750-2500, eastern gamagrass 300-630, spikerush 250-630, alkali cordgrass 150-315, reed canarygrass 150-315, chairmaker's bulrush 100-250, sedge 100-250, shortbeak sedge 100-250, clustered field sedge 100-250.Sub-dominant:

A variety of forbs make up 10% of the plant community.Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

The majority of plants are alive and vigorous. Some mortality and decadence is expected for the site. This in part is due to drought, unexpected wildfire, or a combination of the two events. This would be expected for both dominant and sub-dominant groups. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Plant litter is distributed evenly throughout the site. There is no restriction to plant regeneration due to depth of litter. When prescribed burning is practiced there will be little litter the first half of the growing season. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

6,000-7,200 lbs/acre. Representative value is 7,000 lbs/forage/acre. Below normal precipitation during the growing season expect 6,000 lbs/forage/acre and above normal precipitation during the growing season expect 7,200 lbs/forage/acre. If utilization has occurred, estimate the annual production removed or expected and include this amount when making the total site production estimate. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

None. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

The number and distribution of tillers or rhizomes is assessed relative to the expected production of the perennial warm-season midgrass and shortgrasses.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.