Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R080BY146TX

Clay Loam 26-33" PZ

Last updated: 9/19/2023

Accessed: 03/04/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

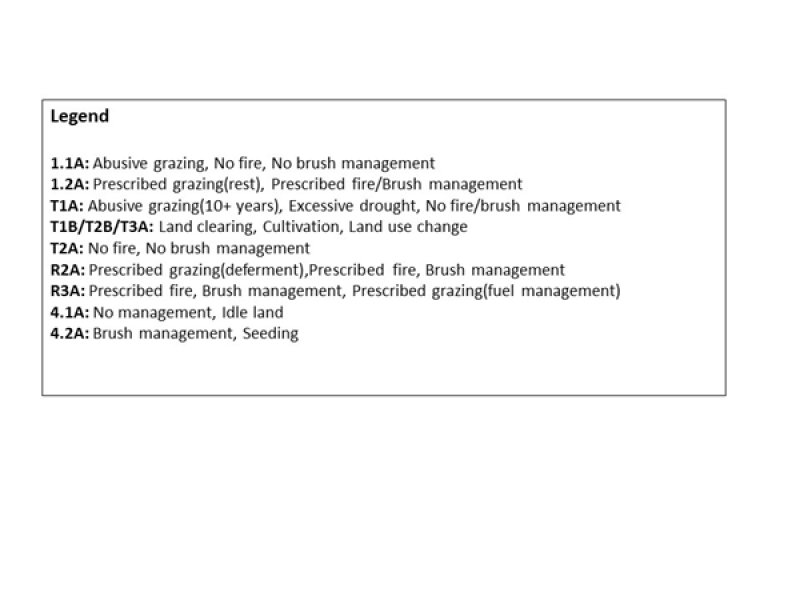

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 080B–Texas North-Central Prairies

MLRA 80B consists of gently rolling, dissected plains with very steep hillsides and sideslopes and narrow flood plains associated with small streams. Loamy and clayey soils range from very shallow to deep and developed in sandstones, shales, and limestones of Pennsylvanian age.

Classification relationships

This ecological site is correlated to soil components at the Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) level which is further described in USDA Ag Handbook 296.

Ecological site concept

These sites occur on moderately deep to deep clay loam soils on terraces and slopes. The reference vegetation consists of a mixture of native tall and midgrasses with scattered forbs and very few woody species. Without fire or other brush management, woody species may increase and dominate the site. These sites are quite susceptible to mesquite invasion.

Associated sites

| R080BY151TX |

Loamy Bottomland 26-33" PZ Clay Loam site frequently occurs immediately adjacent to Loamy Bottomland site. Bottomland sites occur on alluvial soils. |

|---|---|

| R080BY155TX |

Redland 26-33" PZ Clay Loam site frequently occurs immediately adjacent to Redland site. Redland sites are typically lower in carbonates. |

Similar sites

| R080BY607TX |

Clayey Upland 26-33" PZ Similar position on the landscape. Higher clay content. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Schizachyrium scoparium var. scoparium |

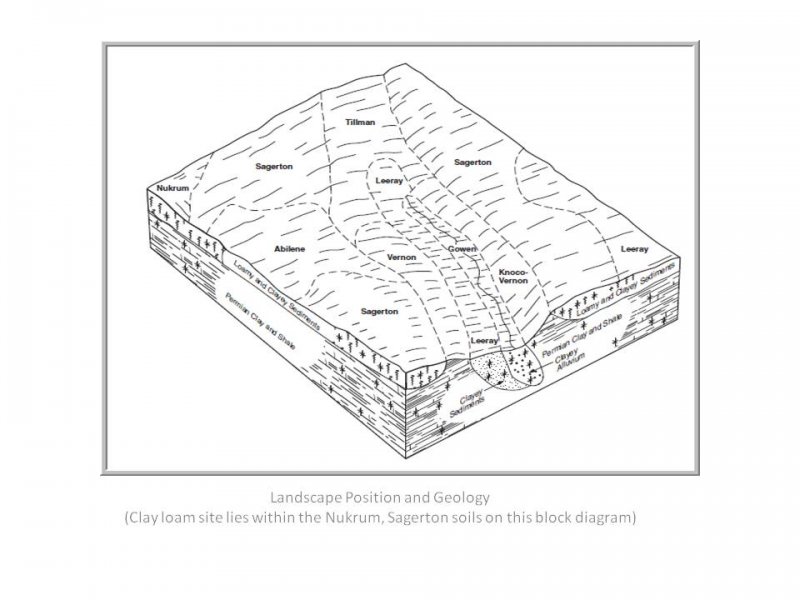

Physiographic features

This site occurs on linear to concave treads of stream terraces or paleoterraces and on base slopes and side slopes of hillslopes in the Texas North-Central Prairies. This site is characteristically a water distributing site. Slopes are typically less than 5 percent.

Figure 2.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Alluvial plain

> Stream terrace

(2) Alluvial plain > Paleoterrace (3) Hills > Hillslope (4) Hills > Ridge |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Low to medium |

| Elevation | 750 – 2,400 ft |

| Slope | 5% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate is subtropical subhumid and is characterized by hot humid summers and relatively mild winters. Tropical maritime air controls the climate during spring, summer and fall. In winter and early spring, frequent surges of polar Canadian air cause sudden drops in temperatures and add considerable variety to the daily weather. The average first frost generally occurs about November 5 and the last freeze of the season usually occurs about March 19. The average frost free period ranges from 215 days in the northern counties, to 240 days in the south.

The average relative humidity in mid-afternoon is about 60 percent in the summer months. Humidity is higher at night, and the average at dawn is about 80 percent. The sun shines 75 percent of the time possible during the summer and 50 percent in winter. The prevailing wind direction is from the southwest and highest wind speeds occur during the spring months.

Approximately 75% of annual rainfall occurs between April 1 and October 31. Rainfall during the months of April through September typically occurs during thunderstorms which tend to be intense and brief, resulting in large amounts of rain in a short time. The wettest months of the year are May, June, September, and October. The driest months during the growing season are July and August. The winter months of November, December, January, and February are the driest months overall.

Average annual precipitation for the entire MLRA is approximately 28 inches. There is a noticeable difference in the average annual precipitation in the northern counties in comparison to the southern and western counties of this Major Land Resource Area. Jack, Young, and Palo Pinto Counties all have an average annual precipitation of more than 31 inches. Stephens, Eastland, McCulloch, and San Saba Counties all have an average annual precipitation of less than 28 inches.

Winters tend to be mild, with occasional periods of very cold temperatures which can be accompanied by strong northerly winds and freezing precipitation. Snow is infrequent and significant accumulations are rare. These periods of very cold weather are generally short-lived. Summers tend to be hot and dry. Drought conditions are common during most summers. Air temperatures of more than 95oF are common from mid-June through September. In the northern counties nearest to the Red River, temperatures are generally slightly cooler during winter months and slightly warmer during summer months than in the other counties in the North Central Prairie.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 184-200 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 211-225 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 30-32 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 183-204 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 210-226 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 29-33 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 193 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 217 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 31 in |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 6. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 7. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 8. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) SAN SABA 7NW [USC00417994], Richland Springs, TX

-

(2) BROWNWOOD 2ENE [USC00411138], Early, TX

-

(3) EASTLAND [USC00412715], Eastland, TX

-

(4) MINERAL WELLS AP [USW00093985], Millsap, TX

-

(5) BRECKENRIDGE [USC00411042], Breckenridge, TX

-

(6) GRAHAM [USC00413668], Graham, TX

-

(7) JACKSBORO [USC00414517], Jacksboro, TX

Influencing water features

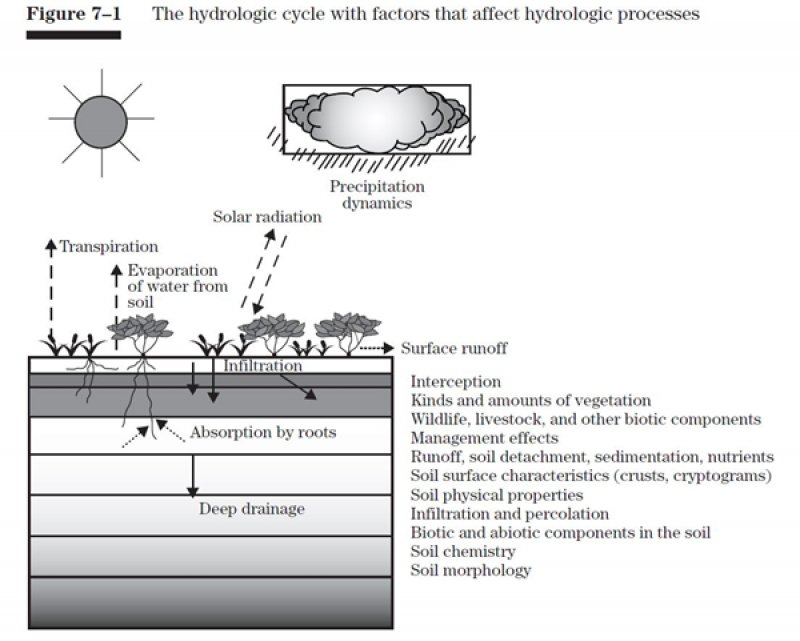

These sites may receive some runoff water from adjacent sites and will also shed some water to areas downslope. The presence of good groundcover and deep rooted perennial grasses can help facilitate water infiltration into the soil. These sites are not associated with wetlands.

Wetland description

NA

Figure 9.

Soil features

Representative soil components for this ecological site include: Sagerton, Velow

The site is characterized by deep to very deep, well drained, moderately slowly permeable soils that formed in calcareous loamy sediments.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

–

limestone and shale

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Clay loam (2) Loam |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow to moderate |

| Soil depth | 60 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 2% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 2% |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

7 – 9 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

40% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

6.6 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (0-40in) |

10% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (0-40in) |

2% |

Ecological dynamics

The reference plant community for the Clay Loam ecological site is a tallgrass/midgrass prairie. Tallgrass species are dominant in the eastern counties in areas receiving more than 30 inches of annual rainfall. Midgrasses are dominant in the western counties of the region in areas receiving less than 30 inches of annual precipitation. Evidence of the historic vegetation can be found in the journals and records of explorers, military expeditions, boundary survey teams, and scientists studying the vegetation.

Climate is a major factor influencing vegetation on the site. Long-term droughts lasting multiple years or growing seasons are infrequent, but when they do occur, they can have a negative impact on the vegetation. If abusive grazing occurs during or immediately following the drought period, the results can be devastating. The effects of erratic seasonal moisture and short-term dry spells lasting a few months are not as severe as those caused by long-term droughts. However, the lower the ecological status of the site, the greater the negative impact will be during drought periods regardless of duration.

Fire was an important part of the ecosystem. Most ecosystems in the North Central Prairie developed in a 4 to 6 year regime of recurring fires. Many of these fires resulted from lightning strikes during thunderstorms. Native Americans frequently set fires to manipulate the movement of bison and other animals as well as a defensive or offensive technique when dealing with their enemies. These historic fires were usually severe because of the amount of grass fuel available to carry the fire. The intensity of fires kept shrubs and sapling trees suppressed and allowed grasses and forbs to flourish. Tallgrass species are fire tolerant and are enhanced by periodic burning. Forbs usually increase for a year or two following these fires before the grasses become dominant again.

Lack of fire allows herbaceous vegetation to become senescent and may eventually lead to the loss of the most desirable species. Seedlings of non-native brush species and invasive weeds may encroach on the site from adjacent areas.

Prior to settlement, this site was subject to periodic grazing and browsing by vast herds of bison, wild cattle, wild horses, and deer. Because of the relatively level and open terrain, vast acreages, quality and quantity of available forage species, and easy access, the Clay Loam site was one of the most frequently used sites by these free-ranging herds. At times these grazing and browsing episodes were intense and severe, but periods of heavy use were followed by long periods of non-use as the herds migrated to fresh grazing areas before returning to previously grazed areas. The grazed areas had an opportunity to rest, regrow, regain vigor, and reproduce prior to the next grazing event. Intervals between grazing periods were frequently influenced by the amount of time that had elapsed since the last fire on the area.

As the region was settled, fire was reduced or eliminated and grasslands were fenced off to control movement and facilitate grazing by domestic livestock. As a result of abusive grazing or lack of grazing and/or the elimination of fire, in association with extreme climatic events, the tallgrass plant community has been eliminated or severely reduced on most Clay Loam sites.

Further deterioration leads to the loss of the perennial warm-season midgrass and forb plant community and an increase in short grasses, annuals, and bare ground. This provides the opportunity for less desirable woody species such as mesquite and juniper to encroach from adjacent sites.

Selective individual removal of undesirable trees and shrubs is relatively easy and more practical when brush plants initially appear on the site. The increase of brush can be fairly rapid and the plants per acre will soon become too numerous for individual control to be feasible. Once woody plants become mature or develop into dense stands, control is expensive, uneconomical, impractical, and difficult to achieve. Brush management is most successful using a systems approach. Initial treatment by mechanical methods can be followed by using approved herbicides, and using prescribed fire as a maintenance technique. Prescribed grazing with a reasonable stocking rate can sustain the grass species composition and production at a near reference community level.

Changes in plant communities and vegetation states on the Clay Loam site are the result of the combined influences of natural events (rainfall, temperature, droughts, etc.) and the accompanying management systems implemented on the area (prescribed fire, grazing management, and brush management).

Rangeland Health Reference Worksheets have been posted for this site on the Texas NRCS website (www.tx.nrcs.usda.gov) in Section II of the eFOTG under (F) Ecological Site Descriptions.

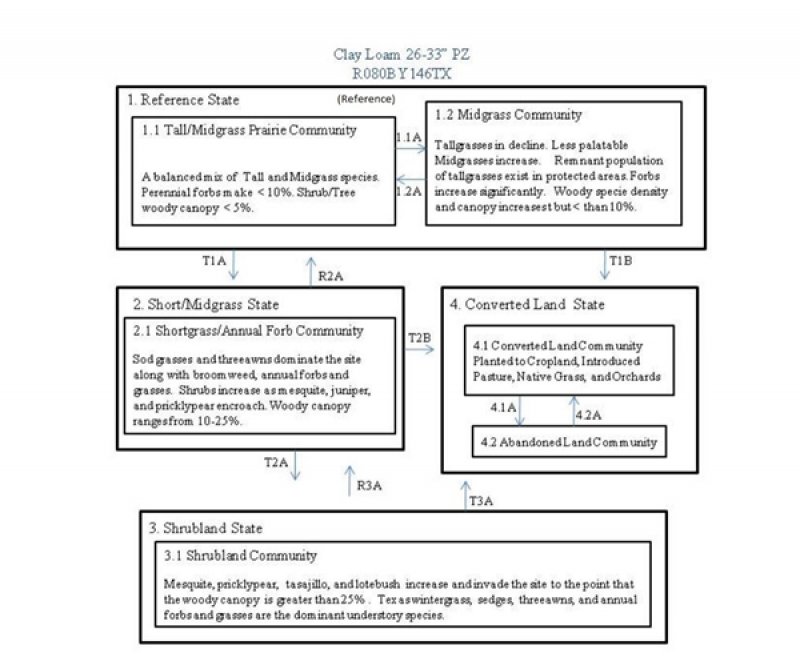

State and Transitional Pathways:

The State and Transition Diagram which follows provides information on some of the most typical pathways that the vegetation on this site can follow as the result of natural events, management inputs, and application of conservation treatments. There may be other plant communities that can exist on this site under certain conditions. Consultation with local experts and professionals is recommended prior to application of practices or management strategies in order to ensure that specific objectives will be met.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Tall/Midgrass Prairie State - Reference

The Tall/Midgrass Prairie Community is an open prairie with a mixture of tallgrasses and midgrasses, some perennial forbs, and a few widely scattered shrubs. The grass species composition varies from the eastern side to the western side of the region. On the western side of the area where average annual precipitation is less than 30 inches, this site is primarily midgrasses and shortgrasses while the site is predominantly tallgrasses in the higher rainfall areas on the eastern side with more than 30 inches of annual precipitation. This is potentially a highly productive site with total annual production ranging from 3600 to 6200 pounds per acre. As tallgrasses decline, midgrasses dominate the Midgrass Prairie Community (1.2). A viable population of little bluestem and other tallgrasses still persists in protected areas on the site. Early successional forbs and shortgrasses begin to increase. The canopy of shrubs and trees begins to gradually increase as mesquite, pricklypear, lotebush, and similar species encroach from adjacent areas. The two communities are maintained by natural fire and weather cycle, and normal graze/rest cycles. This site is most resilient and least resistant to change at this state.

Dominant plant species

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), grass

Community 1.1

Tall/Midgrass Prairie Community

Figure 10. 1.1 Tall/Midgrass Prairie Community

Figure 11. Community Phase 1.1.

The reference plant community for the Clay Loam ecological site in the North Central Prairie region is a tallgrass/midgrass prairie. It is an open prairie with a mixture of tallgrasses and midgrasses, some perennial forbs, and a few widely scattered shrubs. The grass species composition varies from the eastern side to the western side of the region. On the western side of the area where average annual precipitation is less than 30 inches, this site is primarily midgrasses and shortgrasses such as sideoats grama(Bouteloua curtipendula), vine mesquite (Panicum obtusum), Arizona cottontop (Digitaria californica), western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), and buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides), and tallgrasses are sub-dominant. In the higher rainfall areas on the eastern side with more than 30 inches of annual precipitation, the site is predominantly tallgrasses such as little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and eastern gamagrass (Tripsacum dactyloides) with fewer midgrasses and shortgrasses. This is potentially a highly productive site, especially in the higher rainfall areas of this region.

Figure 12. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 3000 | 4250 | 5700 |

| Forb | 400 | 350 | 300 |

| Shrub/Vine | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Total | 3600 | 4800 | 6200 |

Figure 13. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3040, Tallgrass Prairie Community. True tallgrass prairie with Indiangrass, big bluestem, and little bluestem as co-dominants. .

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 22 | 20 | 7 | 4 | 13 | 8 | 3 | 2 |

Community 1.2

Midgrass Community

Figure 14. 1.2 Midgrass Community

Uncontrolled grazing, elimination of fire from the ecosystem, and severe drought conditions result in the transition from a Tall/Midgrass Prairie Community to a Midgrass Prairie Community. As tallgrasses decline, midgrasses such as sideoats grama, vine mesquite, silver bluestem (Bothriochloa laguroides), and dropseeds (Sporobolus spp.) dominate the plant community. A viable population of little bluestem and other tallgrasses still persists in protected areas on the site. Early successional forbs and shortgrasses begin to increase. The canopy of shrubs and trees begins to gradually increase as mesquite, pricklypear (Opuntia spp.), lotebush (Ziziphus obustifolia), and similar species encroach from adjacent areas.

Figure 15. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 1650 | 2700 | 3750 |

| Forb | 450 | 400 | 350 |

| Shrub/Vine | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Total | 2400 | 3400 | 4400 |

Figure 16. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3029, Mid/Shortgrass with Mesquite. Mid and shortgrasses with Mesquite. Sideoats grama, buffalograss, Texas wintergrass, and Meadow dropseed are the dominant grass species for this condition..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 24 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 2 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Structural plant groups change slightly from tallgrass dominant to midgrass dominant. Forb & woody canopy increases. Biomass shift from forage production towards forb and woody production. Uncontrolled (Heavy Continuous) Grazing and No Fires or brush management, may contribute to the Tall/Midgrass Prairie Community shifting to the Midgrass Community.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Introduce fire/brush management to suppress woody cover. Restore ecological process through periodic grazing and browsing. With Prescribed Grazing and Prescribed Burning conservation practices, the Midgrass Community can shift back to the Tall/Midgrass Prairie Community.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 2

Short/Midgrass State

Some natural ecological site processes may have been altered. Loss of tall and midgrass functional and structural plant groups and increase of woody component impart a shift, or a departure from Reference for several indicators. Continued deterioration of the Prairie State eventually results in a Short/Midgrass State dominated by shortgrasses and midgrasses such as buffalograss and curlymesquite. Western ragweed and broomweed are the dominant forbs. Mesquite, pricklypear, juniper, and greenbriar begin to increase in density or invade from adjacent sites. Tallgrasses species and many of the more desired midgrass species are almost completely eliminated from the site, but remnant populations and widely scattered individual plants remain in protected areas. These grasses are often unnoticed because they are grazed very short, are in low vigor, and are not prominent on the site. Annual production ranges from 1500 to 2600 pounds per acre.

Dominant plant species

-

buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides), grass

Community 2.1

Shortgrass Prairie Community

Figure 17. 2.1 Shortgrass Prairie Community

Figure 18. 2.1 Community Phase w/ mesquite and juniper

Figure 19. 2.1 Community Phase w/ stronger forb influence

Figure 20. 2.1 Community Phase

Severe disturbances such as abusive grazing, persistent drought conditions, or combinations of abusive grazing, extreme climatic conditions, and other factors, cause the plant community to change dramatically. Continued deterioration of the plant community eventually results in a plant community dominated by shortgrasses and midgrasses such as buffalograss, curlymesquite(Hilaria belangeri), threeawns (Aristida spp.), Texas wintergrass (Nassella leucotricha), silver bluestem (Bothriochloa laguroides), dropseeds, and tumble windmillgrass (Chloris verticillata). Western ragweed (Ambrosia psilostachya) and broomweed (Amphiachryis dracunculoides) are the dominant forbs. Mesquite, pricklypear, tasajillo (Cylindropuntia leptocaulis), juniper, and greenbriar (Smilax spp.) begin to increase in density or invade from adjacent sites. Bare ground begins to appear in some areas and can become a serious problem in the most deteriorated state. Tallgrasses species and many of the more desired midgrass species are almost completely eliminated from the site, but remnant populations and widely scattered individual plants remain in protected areas. However, they no longer exist in sufficient amounts to allow the site to recover through management alone. These grasses are often unnoticed because they are grazed very short, are in low vigor, and are not prominent on the site.

Figure 21. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 500 | 1000 | 1600 |

| Shrub/Vine | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Forb | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Total | 1500 | 2000 | 2600 |

Figure 22. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3050, Shortgrass Prairie, 20% woody canopy. Shortgrasses are dominant and midgrasses are sub-dominant as tallgrasses are almost totally eliminated. Annuals and early successional forbs and grasses are abundant. Shrubs encroach from adjacent areas and increase in density and canopy..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 20 | 21 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 2 |

State 3

Shrubland State

Numerous natural ecological site processes have been altered. Site is dominated by the woody component. Soil site stability, biotic integrity and the hydrologic function should be evaluated. Loss of tall and midgrass functional and structural plant groups and increase of woody component impart a shift, or a departure from Reference for several indicators. The Shrubland State is composed of brush species such as mesquite, lotebush, pricklypear, and tasajillo which become well established eventually developing a canopy of more than 25% on the site. Annual forbs and grasses as well as early successional grasses and forbs dominate the herbaceous vegetation.

Dominant plant species

-

honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa), shrub

-

lotebush (Ziziphus obtusifolia), shrub

-

pricklypear (Opuntia), shrub

-

Texas wintergrass (Nassella leucotricha), grass

-

tobosagrass (Pleuraphis mutica), grass

Community 3.1

Shrubland Community

Figure 23. 3.1 Shrubland Community

Figure 24. 3.1 Community Phase, shrubland

Continued abusive grazing, lack of fire, and/or severe droughts result in a community dominated by mesquite and other invading species. Brush species such as mesquite, lotebush, pricklypear, and tasajillo become well established eventually developing a canopy of more than 25% on the site. Annual forbs and grasses as well as early successional grasses and forbs dominate the herbaceous vegetation. Annual production ranges from 1500 to 2000 pounds per acre.

Figure 25. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 800 | 800 | 800 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 200 | 400 | 700 |

| Forb | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Total | 1500 | 1700 | 2000 |

Figure 26. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3039, Shortgrass/Annuals/Mesquite/Shrubs Community. Shortgrass/Annuals/Mesquite and Shrubs – buffalograss, curlymesquite, broomweed, annual forbs and grasses, mesquite, lotebush.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 3 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 18 | 12 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 12 | 6 | 3 |

State 4

Converted Land State

Hundreds of thousands of acres have been plowed up and converted to cropland, pastureland, or hayland. This community is known as the Converted Land Community. Wheat is the primary annual crop. Bermudagrass is the primary introduced pasture species used in this area. Abandoned croplands and reseeded areas tend to revert back to a more natural state through the process of secondary succession. This is a very slow process that takes decades or centuries to evolve, dependent on the status of the area at the time it is abandoned. The first plants to establish are “pioneer plants” (annual forbs and grasses followed by early successional shortgrasses and midgrasses). This community is known as the Abandoned Land Community.

Dominant plant species

-

Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), grass

Community 4.1

Converted Land Community

Figure 27. 4.1 Converted Land Community

Figure 28. 4.1 Converted Community Phase

The Clay Loam site is one of the most frequently converted sites because of its deep, fertile soils and level terrain. Hundreds of thousands of acres have been plowed up and converted to cropland, pastureland, or hayland. Wheat is the primary annual crop. Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) is the primary introduced pasture species used in this area. The Clay Loam site can be an extremely productive forage producing site with the application of optimum amounts of fertilizer. Refer to Forage Suitability Group Descriptions for specific recommendations, production potentials, species adaptation, etc. In the highest state of production following conversion, the trees, shrubs and forbs have been severely reduced or eliminated from the site. The more woodies and forbs that occur on a converted site, the lower the overall production would be. The annual production figures below reflect this change.

Figure 29. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 9. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 2000 | 3700 | 5300 |

| Forb | 300 | 250 | 200 |

| Shrub/Vine | 100 | 50 | 0 |

| Total | 2400 | 4000 | 5500 |

Figure 30. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3002, Cropland - Small Grains. Planted into small grains such as wheat or oats..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 5 | 16 | 21 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 18 | 8 |

Figure 31. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3037, Converted Land Community. Planted to monocultures of introduced species, or monocultures or mixtures of commercially available native tallgrasses. .

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 14 | 23 | 20 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 3 | 2 |

Community 4.2

Abandoned Land Community

Thousands of acres of clay loam soils have been broken out and converted to cropland, pastureland, or hayland. In time, many of these cultivated and intensively managed areas have been abandoned because of adverse economic conditions. These abandoned lands have deteriorated to the point that they will never return to historical vegetation because of soil degradation and lack of natural seed source. Abandoned croplands and reseeded areas tend to revert back to a more natural state through the process of secondary succession. This is a very slow process that takes decades or centuries to evolve, dependent on the status of the area at the time it is abandoned. The first plants to establish are “pioneer plants” (annual forbs and grasses followed by early successional shortgrasses and midgrasses). If managed properly, some of these abandoned areas may eventually begin to approximate the diversity and complexity of the native Clay Loam ecosystem. Midgrasses, perennial forbs, and tallgrasses may begin to establish if the area is carefully managed. However, it is highly unlikely that abandoned lands can ever return to reference vegetation within a reasonable period of time.

Figure 32. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 10. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forb | 300 | 400 | 500 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 200 | 300 | 400 |

| Shrub/Vine | 100 | 200 | 300 |

| Total | 600 | 900 | 1200 |

Figure 33. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3018, Secondary Succession - Annuals/forbs.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

Pathway 4.1A

Community 4.1 to 4.2

Abusive Grazing, No Fire, No Brush Management, Idle Land, No Pasture/ Orchard/Cropland Management, may contribute a shift to the Abandoned Land Community.

Pathway 4.2A

Community 4.2 to 4.1

Re-introduction of fire or brush management suppresses woody cover. Re-introduction of management is necessary to maintain health and productivity for Pasture/Cropland/Orchard. Restoration of ecological processes through periodic grazing and browsing. With the implementation of various conservation practices such as Prescribed Grazing, Prescribed Burning, Pasture/Crop/Orchard Management, Seedbed Preparation, and Range/Pasture/Tree Planting, the Abandoned Land Community can be shifted back to the Converted Land Community.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Range Planting | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Functional and Structural plant changes and an increase of bare ground, reduced production, litter accumulation and infiltration. Increased erosion potential. Nutrient cycle disrupted. Triggers: Functions of miss-managed grazing and/or drought, plus an interruption of natural fire interval. Triggered by natural events, management actions or both. State can transition into the Short/Midgrass Prairie State.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 4

The Tall/Midgrass Prairie State can transition into the Converted Land State with land conversion through Seedbed Preparation, and Range , Pasture, Tree or Crop PlantingWith Seedbed Preparation, Range Planting, Pasture Planting, Crop Cultivation and Orchards.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Management and restoration practices must decrease mesquite, pear, and juniper cover with limited surface disturbance. Restoration activities such as rest/rotation programs, and Prescribed Burning can improve herbaceous production and allow for litter accumulation to improve organic matter inputs to stabilize soil surface. The Short/Midgrass State can be restored to the Tall/Midgrass Prairie State.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting |

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Complete loss of several Functional and Structural plant groups leads to an increase of bare ground, reduced production, litter accumulation and infiltration. Increased erosion potential. Nutrient cycle disrupted. Triggers: Functions of long-term miss-managed grazing and/or drought, plus an interruption of natural fire interval. State will shift to the Shrubland State.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

Land conversion through Seedbed Preparation, and Range , Pasture, Tree or Crop Planting. The Short/Midgrass State can transition into the Converted Land State.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 2

Management and restoration practices must decrease woody and/or pear cover . Natural seed source for mid/tall grasses may be lost. Seedbed Preparation, and Range Planting may be necessary. Restoration activities such as rest/rotation programs, and brush management are required to restore site productivity. The Shrubland State can be restored to the Short/Midgrass State.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting |

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Land conversion through Seedbed Preparation, and Range , Pasture, Tree or Crop PlantingThe Shrubland State can transition into the Converted Land State.

Additional community tables

Table 11. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Tallgrass | 650–1850 | ||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | 650–1850 | – | ||

| 2 | Tallgrasses | 650–1250 | ||||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 0–1250 | – | ||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 0–950 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 0–600 | – | ||

| eastern gamagrass | TRDA3 | Tripsacum dactyloides | 0–600 | – | ||

| 3 | Midgrasses | 300–1050 | ||||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 150–1050 | – | ||

| vine mesquite | PAOB | Panicum obtusum | 0–650 | – | ||

| 4 | Midgrasses | 300–750 | ||||

| silver beardgrass | BOLAT | Bothriochloa laguroides ssp. torreyana | 100–600 | – | ||

| cane bluestem | BOBA3 | Bothriochloa barbinodis | 0–450 | – | ||

| Arizona cottontop | DICA8 | Digitaria californica | 0–300 | – | ||

| composite dropseed | SPCOC2 | Sporobolus compositus var. compositus | 0–300 | – | ||

| Drummond's dropseed | SPCOD3 | Sporobolus compositus var. drummondii | 0–300 | – | ||

| purpletop tridens | TRFL2 | Tridens flavus | 0–200 | – | ||

| Texas cupgrass | ERSE5 | Eriochloa sericea | 0–200 | – | ||

| seep muhly | MURE2 | Muhlenbergia reverchonii | 0–100 | – | ||

| marsh bristlegrass | SEPA10 | Setaria parviflora | 0–100 | – | ||

| plains lovegrass | ERIN | Eragrostis intermedia | 0–100 | – | ||

| tall grama | BOHIP | Bouteloua hirsuta var. pectinata | 0–100 | – | ||

| 5 | Cool-season grasses | 50–300 | ||||

| Texas wintergrass | NALE3 | Nassella leucotricha | 50–300 | – | ||

| Canada wildrye | ELCA4 | Elymus canadensis | 0–150 | – | ||

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | 0–150 | – | ||

| Scribner's rosette grass | DIOLS | Dichanthelium oligosanthes var. scribnerianum | 0–100 | – | ||

| western wheatgrass | PASM | Pascopyrum smithii | 0–100 | – | ||

| 6 | Mid/Shortgrasses | 150–500 | ||||

| buffalograss | BODA2 | Bouteloua dactyloides | 50–500 | – | ||

| blue grama | BOGR2 | Bouteloua gracilis | 0–150 | – | ||

| white tridens | TRAL2 | Tridens albescens | 0–150 | – | ||

| slim tridens | TRMUE | Tridens muticus var. elongatus | 0–100 | – | ||

| slim tridens | TRMUM | Tridens muticus var. muticus | 0–100 | – | ||

| hooded windmill grass | CHCU2 | Chloris cucullata | 0–100 | – | ||

| fall witchgrass | DICO6 | Digitaria cognata | 0–100 | – | ||

| curly-mesquite | HIBE | Hilaria belangeri | 0–100 | – | ||

| Hall's panicgrass | PAHAH | Panicum hallii var. hallii | 0–100 | – | ||

| hairy grama | BOHI2 | Bouteloua hirsuta | 0–100 | – | ||

| purple threeawn | ARPU9 | Aristida purpurea | 0–100 | – | ||

| Wright's threeawn | ARPUW | Aristida purpurea var. wrightii | 0–100 | – | ||

| Texas grama | BORI | Bouteloua rigidiseta | 0–50 | – | ||

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | 0–50 | – | ||

| crowngrass | PASPA2 | Paspalum | 0–50 | – | ||

| hairy woollygrass | ERPI5 | Erioneuron pilosum | 0–50 | – | ||

| rosette grass | DICHA2 | Dichanthelium | 0–50 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 7 | Forbs | 100–300 | ||||

| Texas Indian mallow | ABFR3 | Abutilon fruticosum | 0–200 | – | ||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 0–200 | – | ||

| white sagebrush | ARLUM2 | Artemisia ludoviciana ssp. mexicana | 0–200 | – | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–200 | – | ||

| Berlandier's sundrops | CABE6 | Calylophus berlandieri | 0–200 | – | ||

| American star-thistle | CEAM2 | Centaurea americana | 0–200 | – | ||

| whitemouth dayflower | COER | Commelina erecta | 0–200 | – | ||

| prairie clover | DALEA | Dalea | 0–200 | – | ||

| purple prairie clover | DAPU5 | Dalea purpurea | 0–200 | – | ||

| Illinois bundleflower | DEIL | Desmanthus illinoensis | 0–200 | – | ||

| ticktrefoil | DESMO | Desmodium | 0–200 | – | ||

| Engelmann's daisy | ENPE4 | Engelmannia peristenia | 0–200 | – | ||

| Leavenworth's eryngo | ERLE11 | Eryngium leavenworthii | 0–200 | – | ||

| beeblossom | GAURA | Gaura | 0–200 | – | ||

| curlycup gumweed | GRSQ | Grindelia squarrosa | 0–200 | – | ||

| hoary false goldenaster | HECA8 | Heterotheca canescens | 0–200 | – | ||

| starviolet | HEDYO2 | Hedyotis | 0–200 | – | ||

| Indian rushpea | HOGL2 | Hoffmannseggia glauca | 0–200 | – | ||

| trailing krameria | KRLA | Krameria lanceolata | 0–200 | – | ||

| Texas skeletonplant | LYTE | Lygodesmia texana | 0–200 | – | ||

| Nuttall's sensitive-briar | MINU6 | Mimosa nuttallii | 0–200 | – | ||

| yellow puff | NELU2 | Neptunia lutea | 0–200 | – | ||

| evening primrose | OENOT | Oenothera | 0–200 | – | ||

| pitcher sage | SAAZG | Salvia azurea var. grandiflora | 0–200 | – | ||

| false gaura | STLI2 | Stenosiphon linifolius | 0–200 | – | ||

| white heath aster | SYERE | Symphyotrichum ericoides var. ericoides | 0–200 | – | ||

| slender greenthread | THSI | Thelesperma simplicifolium | 0–200 | – | ||

| prairie spiderwort | TROC | Tradescantia occidentalis | 0–200 | – | ||

| Texas vervain | VEHA | Verbena halei | 0–200 | – | ||

| Maximilian sunflower | HEMA2 | Helianthus maximiliani | 0–100 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 8 | Trees/Shrubs/Vines | 50–200 | ||||

| sugarberry | CELAL | Celtis laevigata var. laevigata | 0–200 | – | ||

| netleaf hackberry | CELAR | Celtis laevigata var. reticulata | 0–200 | – | ||

| pricklypear | OPUNT | Opuntia | 0–100 | – | ||

| honey mesquite | PRGL2 | Prosopis glandulosa | 0–100 | – | ||

| fragrant sumac | RHAR4 | Rhus aromatica | 0–100 | – | ||

| prairie sumac | RHLA3 | Rhus lanceolata | 0–100 | – | ||

| bully | SIDER2 | Sideroxylon | 0–100 | – | ||

| pricklyash | ZANTH | Zanthoxylum | 0–100 | – | ||

| lotebush | ZIOB | Ziziphus obtusifolia | 0–100 | – | ||

| catclaw acacia | ACGRG3 | Acacia greggii var. greggii | 0–100 | – | ||

| jointfir | EPHED | Ephedra | 0–50 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Historically, the Clay Loam site was inhabited permanently and intermittently by a variety of grassland mammals, reptiles, and birds. Several historical references and journals written in the 18th and 19th century by explorers, survey parties, and military expeditions refer to herds of bison, wild cattle, wild horses, deer, and antelope roaming freely across the North Central Prairie and adjacent regions. The Clay Loam site was one of the most frequently used sites by these free-ranging herds because of the relatively level and open terrain, quality and quantity of available forage species, vast acreages, and easy access.

Currently, the site is utilized by quail, dove, numerous species of grassland birds, and a variety of small fur-bearing mammals. Quail and dove utilize the site more frequently in the midgrass, Shortgrass, and shrubland plant community phases. White-tailed deer and turkey use the site intermittently in association with adjacent sites if sufficient shrub and tree canopy exists. Feral hogs are also frequent visitors to the site in some areas. Animal species and populations fluctuate as the vegetation cycles through temporary phases and different ecological stages.

Livestock grazing should be controlled by implementing grazing management systems that incorporate frequent and timely deferment periods to prevent abusive grazing.

Hydrological functions

When herbaceous vegetation and ground cover are maintained in a healthy and vigorous status, water infiltration into the soil profile is increased significantly, resulting in less runoff. A thick, healthy grass cover also results in improved water quality because it serves as a filter or trap to reduce sediments and pollutants before the water flows offsite.

Recreational uses

The Clay Loam ecological site provides limited outdoor activities such as bird watching, hiking, camping, horseback riding, and off-road vehicle use. Some Clay Loam sites provide good habitat for quail and dove hunting. Deer and turkey hunting is severely limited by the lack of browse, mast, and escape cover.

Wood products

Mesquite wood can be used for firewood and fence posts.

Other products

None.

Other information

None.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Vegetation data for this site was obtained from existing Range Site Descriptions, SCS-RANGE -417 Production and Composition Records for Native Grazing Lands, and on-site inventories by the author and local experts including ranchers, natural resource specialists from federal and state agencies, and personnel from cooperating agencies and organizations. A total of 14 SCS-RANGE-417’s containing data collected from 4 counties (Lampasas, Palo Pinto, Throckmorton, and Young) during the period 12/30/1981 to 12/12/1986 were reviewed for this site.

References

-

. 2021 (Date accessed). USDA PLANTS Database. http://plants.usda.gov.

-

Bailey, V. 1905. Biological Survey of Texas. North American Fauna 25:1–222.

Other references

Ajilvsgi, Geyata. Wildflowers of Texas. Sharer Publishing, Bryan, TX. 1984.

Bachand, Richard. The American Prairie: Going, Going, Gone? National Wildlife Federation. Rocky Mountain Natural Resource Center. Boulder, CO. 2001.

Burleson, Bob and Mickey. Personal communication. 9/30/2007

Burns, Paul. Personal communication. 10/4/2007.

Coffey, Chuck R., and Russell Stevens. Grasses of Southern Oklahoma and North Texas: A Pictorial Guide. The Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation, Ardmore, OK. 2004

Diggs, George M., Jr., Barney L. Lipscomb, and Robert J. O’Kennon. Illustrated Flora of North Central Texas. Botanical Research Institute of Texas. Fort Worth, TX 1999.

Egan, Dave and Evelyn A. Howell. The Historical Ecology Handbook…A Restorationist’s Guide to Reference Ecosystems. Island Press, Washington, DC. 2001.

Enquist, Marshall. Wildflowers of the Texas Hill Country. Lone Star Botanical, Austin, TX. 1987.

Flores, Dan. “Indian Use of Range Resources” presented at 20th Annual Ranch Management Conference. Lubbock, TX, September 30, 1983.

Gould, Frank W., The Grasses of Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX. 1975.

Hatch, Stephan L., Kancheepuram N. Gandhi, and Larry E. Brown. Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Texas. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station MP-1655. College Station, TX. 1990

Hatch, Stephan L., Jennifer Pluhar. Texas Range Plants. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX. 1993.

Johnson, Rhett. Personal communication. 9/18/2007.

Kelton, Elmer. “History of Rancher Use of Range Resources” presented at 20th Annual Ranch Management Conference. Lubbock, TX, September 30, 1983.

Ladd, Doug. Tallgrass Prairie Wildflowers. Falcon Press, Helena and Billings, MT. 1995.

Larrabee, Aimee and John Altman. Last Stand of the Tallgrass Prairie. Sterling Publishing Co., New York, NY. 2001.

Merz, Dalton. Personal communication. 9/29/2007.

Nelson, Paul W. The Terrestrial Natural Communities of Missouri. Missouri Department of Natural Resources. 1985.

Packard, Stephen and Cornelia F. Mutel. The Tallgrass Restoration Handbook for Prairies, Savannas, and Woodlands. Island Press, Washington, DC. 1997.

Parker, W.B. Through Unexplored Texas In The Summer and Fall of 1854. The Texas State Historical Commission. Austin, TX 1984

Smith, Jared G. Grazing Problems in the Southwest and How to Meet Them. United States Department of Agriculture Division of Agrostology. Washington, DC. 1899.

Texas Almanac Sesquicentennial Edition 1857-2007. Dallas Morning News. Dallas, TX. 2006.

Tyrl, Ronald J., Terrence G. Bidwell, and Ronald E. Masters. Field Guide to Oklahoma Plants. Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK. 2002.

United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA. The PLANTS Database. http://plants.usda.gov 2007.

United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, Ag Handbook 296. Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. 2006.

United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, Temple, TX. Clay Loam Ecological Site Descriptions R078CY096TX, R084BY170TX, R085XY181TX, and R086AY199TX. 2006.

United States Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service, Temple, TX. Production and Composition Record for Native Grazing Lands. SCS-RANGE 417 data from Brown, Eastland, Jack, Stephens, and Young Counties. 1981-1986.

United States Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service, Washington, DC. Web Soil Survey http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/. 2007

United States Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service, Temple, TX. Published Soil Surveys: Brown and Mills, Jack, Palo Pinto, Stephens, and Young Counties. Various publication dates.

United States Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service, Temple, TX. Range Site Descriptions for the North Central Prairie counties. Various publication dates.

Vines, Robert A. Trees of North Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX. 1982

Weniger, Del. The Explorers’ Texas. Eakin Publications. Austin, TX. 1984.

Williams, Gerald W. References On The American Indian Use Of Fire in Ecosystems. United States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service, Washington, DC. 2005.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: I would like to express my thanks and appreciation to the following for their cooperation, assistance, and support in the development of this Ecological Site Description:

Bob and Mickey Burleson, landowners – Temple, TX

Tony Dean, NRCS – Henrietta, TX

Fort Richardson State Park – Jacksboro, TX

Matt Gregory, NRCS – Jacksboro, TX

John Hackley, rancher – Jacksboro, TX

Lake Brownwood State Park – Brownwood, TX

Ricky Marks, NRCS – Brownwood, TX

Dalton Merz, rancher – Holland, TX

Misty Pearcy, NRCS – Brownwood, TX

Richards Ranch – Jacksboro, TX

Reviewers:

Lem Creswell, RMS, NRCS, Weatherford, Texas

Kent Ferguson, RMS, NRCS, Temple, Texas

Justin Clary, RMS, NRCS, Temple, Texas

Contributors

Dan Caudle, DMC Resource Management, Weatherford, Texas

Approval

Bryan Christensen, 9/19/2023

Acknowledgments

Site Development and Testing Plan:

Future work, as described in a Project Plan, to validate the information in this Provisional Ecological Site Description is needed. This will include field activities to collect low, medium and high intensity sampling, soil correlations, and analysis of that data. Annual field reviews should be done by soil scientists and vegetation specialists. A final field review, peer review, quality control, and quality assurance reviews of the ESD will be needed to produce the final document. Annual reviews of the Project Plan are to be conducted by the Ecological Site Technical Team.

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Lem Creswell, Zone RMS, NRCS, Weatherford, Texas |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | 817-596-2865 |

| Date | 10/17/2007 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Deposition or erosion is uncommon during normal rainfall events, but may occur in limited areas during intense rainfall events. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

None. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Expect no more than 10% bare ground scattered randomly throughout the site. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

Few rills and no gullies should occur. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Little or no litter movement or deposition during normal rainfall events. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil surface in HCPC is resistant to wind erosion. Stability range is expected to be 5-6. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

0-8 inches of brown clay loam. SOM is 1-6%. See soil survey for more information. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

The tallgrass/midgrass prairie with adequate litter, and little bare ground provides for maximum infiltration and negligible runoff. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm-season tallgrasses > Warm-season midgrasses >Sub-dominant:

Warm-season shortgrasses >Other:

Forbs > Cool-season grasses > Trees > Shrubs/VinesAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Perennial grasses will naturally exhibit a minor amount (less than 5%) of senescence and some mortality every year. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Litter is primarily herbaceous. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

3,600 to 6,200 pounds per acre. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Mesquite, lotebush, pricklypear, tasajillo, pricklyash, juniper, King Ranch bluestem, annual broomweed. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All perennial species should be capable of reproducing every year unless disrupted by extended drought, overgrazing, wildfire, insect damage, or other events occuring immediately prior to, or during the reproductive phase.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.