Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R081AY291TX

Clay Loam 14-19 PZ

Last updated: 9/19/2023

Accessed: 03/05/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

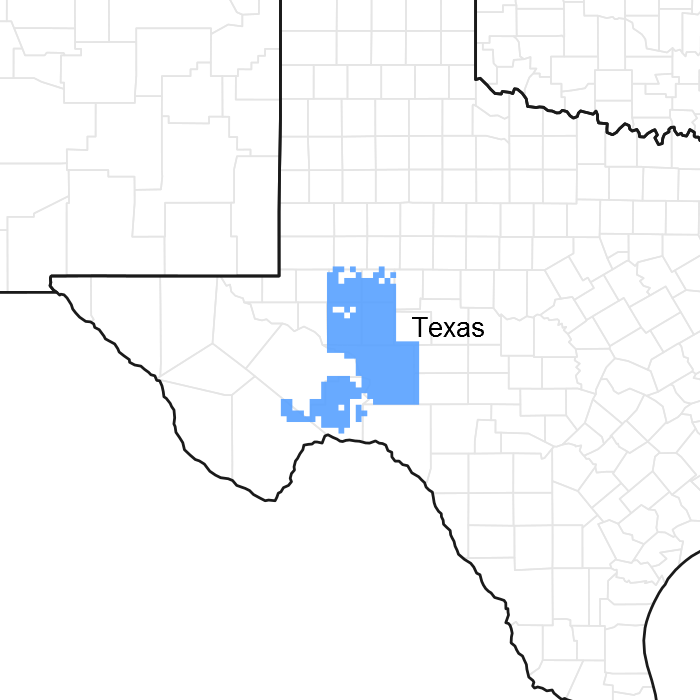

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 081A–Edwards Plateau, Western Part

This area is entirely in Texas. It makes up about 16,550 square miles (42,885 square kilometers). The cities of San Angelo and Fort Stockton and the towns of Big Lake, McCamey, Ozona, and Sheffield are in this MLRA. Interstate 20 crosses the northern part of the area, and Interstate 10 crosses the middle of the area. The eastern part of Amistad National Recreation Area is in this MLRA.

Classification relationships

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006.

-Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 81A

Ecological site concept

The Clay Loam has deep, clay loam textures and has high vegetative production. Soils are generally brown, well drained, and moderately permeable.

Associated sites

| R081AY311TX |

Shallow 14-19 PZ The Shallow ecological site has shallow soils. |

|---|---|

| R081AY303TX |

Loamy 14-19 PZ The Loamy ecological site are higher in the landscapes on ridges and sideslopes. |

| R081AY309TX |

Low Stony Hill 14-19 PZ The Low Stony Hill ecological site has shallow soils. |

| R081AY566TX |

Limestone Hill 14-19 PZ The Limestone Hill ecological site has shallow soils. |

| R081AY290TX |

Clay Flat 14-19 PZ The Clay Flat ecological site has higher clay content and has the potential to be ponded. |

| R081AY306TX |

Loamy Bottomland 14-19 PZ The Loamy Bottomland ecological site occurs lower in the landscapes on floodplains. |

Similar sites

| R081AY303TX |

Loamy 14-19 PZ The Loamy ecological site are higher in the landscapes on ridges and sideslopes. |

|---|---|

| R081AY290TX |

Clay Flat 14-19 PZ The Clay Flat ecological site has deep soils with higher clay content. |

| R081AY306TX |

Loamy Bottomland 14-19 PZ The Loamy Bottomland ecological site has deep soils with flooding. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Prosopis glandulosa |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Bouteloua curtipendula |

Physiographic features

Soils occur on nearly level to gently sloping stream terraces, valleys, and plains. Slopes range from 0 to 3 percent. Elevation of this site ranges from 1,500 to 2,750 feet above sea level. This site will receive runoff from Limestone Hill, Low Stony Hill and Loamy ecological sites that usually occur along the site’s boundary.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Alluvial plain

> Plain

(2) River valley > Valley (3) River valley > Stream terrace |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Low to medium |

| Flooding duration | Brief (2 to 7 days) |

| Flooding frequency | None to rare |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 1,500 – 2,750 ft |

| Slope | 3% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate is semiarid and is characterized by hot summers and dry, relatively mild winters. The average relative humidity in mid-afternoon ranges from 25 to 50 percent. Humidity is higher at night, and the average at dawn is around 70 to 80 percent. The sun shines 80 percent of the time during the summer and 60 percent in winter. The prevailing wind is from the south-southwest. Approximately two-thirds of annual rainfall occurs during the May to October period. Rainfall during this period generally falls during thunderstorms, and fairly large amounts of rain may fall in a short time. The climate is one of extremes, which exert much more influence on plant communities than averages. Timing and amount of rainfall are critical. High temperatures and dry westerly winds have a tremendously negative impact on precipitation effectiveness, as well as length of time since the last rain. Records since the mid-1900’s, as well as geological and archaeological findings, indicate wet and dry cycles going back many thousands of years and lasting for various lengths of time with enormous influence on the flora and fauna of the area.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 210-240 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 240-280 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 15-19 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 210-240 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 240-280 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 15-23 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 225 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 255 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 18 in |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BAKERSFIELD [USC00410482], Iraan, TX

-

(2) COPE RCH [USC00411974], Big Lake, TX

-

(3) GARDEN CITY [USC00413445], Garden City, TX

-

(4) MCCAMEY [USC00415707], Mc Camey, TX

-

(5) PAINT ROCK [USC00416747], Paint Rock, TX

-

(6) PANDALE 1 N [USC00416780], Comstock, TX

-

(7) PANDALE 11 NE [USC00416781], Comstock, TX

-

(8) SANDERSON [USC00418022], Dryden, TX

-

(9) SHEFFIELD [USC00418252], Sheffield, TX

-

(10) BIG LAKE 2 [USC00410779], Big Lake, TX

Influencing water features

Some areas may be flooded, but only rarely. Flooding occurs from adjacent waterways when excess precipitation occurs for brief periods of 2 to 7 days.

Wetland description

N/A

Soil features

These are very deep, well drained, slowly to moderately permeable and formed in calcareous silty, loamy and clayey alluvium. The soils of this site are dark to very dark grayish brown deep silty clay loams, silty clays, and clays. Few limestone pebbles are present in the profile, and their influence on production of native plants is negligible. Plant-soil-air-moisture relationships are good. In healthy conditions, rills, gullies, wind-scoured areas, pedestals, and soil compaction layers are not present on the site. The following soil series are associated with the Clay Loam ecological site: Angelo, Rio Diablo, and Texon.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

–

limestone

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Silty clay loam (2) Clay loam (3) Silt loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Fine (2) Fine-silty |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow to moderate |

| Soil depth | 60 – 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 6% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 1% |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

5.5 – 7.9 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

5 – 30% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

7.4 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (10-40in) |

5 – 16% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (10-40in) |

2% |

Table 5. Representative soil features (actual values)

| Drainage class | Not specified |

|---|---|

| Permeability class | Slow to moderate |

| Soil depth | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (10-40in) |

Not specified |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (10-40in) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

The plant communities of this site are dynamic entities. In pre-settlement times, a Clay Loam site would most likely be a savannah dotted with mesquite trees, occasional shrubs and, in some areas, live oaks. The surface would be mostly covered by mid-size bunch grasses and perennial forbs. This reference plant community was greatly influenced by grazing, climate (including periodic extended periods of drought) and, to a lesser degree, fire.

Extensive herds of pronghorns, large towns of black-tailed prairie dogs, as well as smaller populations of elk, white-tailed deer, and desert mule deer were present and had an impact on the plant community. Bison, a migratory herd animal, would come into an area, graze on the move, and not come back for many months or even years. This long deferment period allowed the plants to recover from the heavy grazing. Bison grazing on this site was probably intermittent, occurring during wetter periods. Very few bison were reported in the area after 1830. There were no recorded sightings after 1860. Fire has an influence on plant community structure and was probably a factor in maintaining the original savannah vegetation. Mesquite were present on the site, but not at the level seen today. Periodic fires may have helped keep mesquite as a scattered savannah and other woody species a small part of the composition. Grazing patterns by native herbivores and prairie dog activities were probably more significant factors in maintaining a well-balanced plant community.

Reference community plants developed ways to withstand periods of drought. The midgrasses and forbs shaded the ground, reduced soil temperature, improved infiltration of what little moisture might fall and maintained soil moisture longer. Their roots reached deeper into the soil, utilizing deep soil moisture no longer available to short-rooted plants. In extreme cases many species could go virtually dormant, preserving the energy stored in underground roots, crowns and stems until wetter weather arrived. Their seeds could stay viable in the soil for long periods, sprouting when conditions improved.

While grazing is a natural component of this ecosystem, overstocking and thus overgrazing by domesticated animals has had a tremendous impact on the site. Early settlers, accustomed to farming and ranching in more temperate zones of the eastern United States or even Europe, misjudged the capacity of the site for sustainable production and expected more of the site than it could deliver. Moreover, there was a gap of time between the extirpation of bison and the introduction of domestic livestock which resulted in an accumulation of plant material. This may have given the illusion of higher production than was actually being produced. Overgrazing and fire suppression disrupted ecological processes that took hundreds or thousands of years to develop. Instead of grazing and moving on, domestic livestock were present on the site most of the time, particularly after the practice of fencing arrived. Another influence on grazing patterns was the advent of wells and windmills. They opened up large areas that were previously unused by livestock due to lack of natural surface water. The more palatable plants were selected repeatedly and eventually began to disappear from the ecosystem to be replaced by lower successional, less palatable species. As overgrazing continued, overall production of grasses and forbs declined, more bare ground appeared, soil erosion increased, and woody and succulent increasers began to multiply. The elimination of fire due to the lack of fine fuel or by human interference assisted the rapid encroachment of mesquite and other woody increasers and a concurrent reduction of usable forage.

The Clay Loam Site had a positive influence on infiltration and percolation of rainfall into plant root zones. Loss of soil organic matter has a negative impact on infiltration and results in soil compaction. More rainfall is directed to overland flow, which increases soil erosion and decreases infiltration of moisture to plant roots. Pedestalling, terracetes, and water-flow patterns are range health indicators that will be present if the site begins to deteriorate. The mineral content and reaction of these soils enable the site to produce highly nutritious forage. In association with other sites, the Clay Loam site is usually the preferred grazing area.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of natural disturbance regimes |

| T2A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, coupled with drought conditions |

| T3A | - | Removal of woody canopy followed by rangeland seeding |

| T4A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Midgrass Savannah

Dominant plant species

-

sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), grass

-

silver beardgrass (Bothriochloa laguroides), grass

Community 1.1

Midgrass Savannah

The reference plant community for this site is a savannah composed of midgrasses with scattered trees and shrubs which have evolved under the influence of grazing, periodic fire, and fluctuations between wet and dry periods, often lasting years at a time. The production on the site varies greatly over the years due to the episodic nature of the rainfall. The overstory shades up to 10 percent of the site and consists primarily of mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa), hackberry (Celtis laevigata), western soapberry (Sapindus saponaria), and occasional live oaks (Quercus virginiana), with shrubs such as algerita (Mahonia trifoliata), ephedra (Ephedra spp.), littleleaf sumac (Sumac spp.), condalia (Condalia spp.), wolfberry (Symphoricarpos orbiculatus), and fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens). Mesquite tree size diminishes from east to west. Midgrasses such as sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), cane bluestem (Bothriochloa barbinoidis), silver bluestem (Bothriochloa laguroides), and plains bristlegrass (Setaria leucopila) dominate the site. Subdominants include Arizona cottontop (Digitaria californica), buffalograss (Buchloe dactyloides), tobosa (Hilaria mutica), Texas wintergrass (Nassella leucotricha), and Canada wildrye (Elymus canadensis). Perennial forbs are a small, but important, component of the plant community. Plants are vigorous and reproduction by rhizome, stolon or seed is rapid during favorable weather. Bare ground is less than 25 percent. Interspaces between plants are mostly covered with litter. The soil surface is relatively cool, moderately rich in humus, and hosts a healthy microbe population actively decomposing organic matter. Soil erosion is insignificant. Infiltration is complete for most rainfall events and runoff occurs only during heavy rains when overland flow is high. Concentrated water flow patterns are rare. Recurrent fire, climatic patterns and grazing by bison, pronghorn and other herbivores were natural processes that maintained this historic plant community. Interruption of the ecological processes of a site brings about change. The reference plant community included large populations of desirable grasses and forbs. However, continued overuse and drought have resulted in their disappearance from large portions of the site. As fire is eliminated and overstocking becomes continual, the more palatable grasses such as sideoats grama, cane bluestem, Texas cupgrass (Eriochloa sericea), Arizona cottontop, plains bristlegrass, Canada wildrye, and vine mesquite (Panicum obtusum) decrease as do the palatable perennial forbs, while unpalatable short and annual grasses and forbs, shrubs, succulents, and trees take the place of these more desirable plant species. Encroachment by small mesquite, various shrubs and prickly pear cactus commences. More bare ground appears. The diversity of native forbs and grasses has been significantly reduced, while the presence of introduced and native invader species seems to be increasing annually. The community shifts toward the Mid and Shortgrass Mesquite Savannah Community. With institution of sound management practices, however, this trend can be reversed, and a measure of productivity restored. Understanding the ecology of the site and use of sound grazing management, individual plant treatment and prescribed burning where practical are keys to any attempts to return to the reference community.

Figure 8. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 1020 | 1700 | 2210 |

| Shrub/Vine | 60 | 100 | 130 |

| Tree | 60 | 100 | 130 |

| Forb | 60 | 100 | 130 |

| Total | 1200 | 2000 | 2600 |

Figure 9. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3254, Midgrass Savannah Community. Dominated by warm season grasses with small percentages of forbs, shrubs, and trees. Growth is dependent on rainfall events..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 5 | 4 |

Community 1.2

Mid/Shortgrass Mesquite Savannah

This community still resembles a midgrass savannah plant structure to casual observation. However, due to the measurable decline of dominant midgrasses caused by overstocking, elimination of fire, lack of brush management and, possibly changes in weather patterns, the population of mesquite and other woody species begins to increase. Vigor and reproduction of the historically dominant grass species decline, and they are starting to be replaced by tobosa, buffalograss, curlymesquite (Hilaria belangeri), slim tridens (Tridens muticus), Hall’s panicum (Panicum hallii) and other short grasses. Less palatable annual and perennial forbs increase. Ground cover by litter decreases. Up to 40 percent of the ground is bare. Soil organic matter is decreasing. Infiltration begins to drop off and runoff increases. Signs of erosion begin to appear. The loss of topsoil and soil organic matter makes it very hard for these abused areas to return to the historic plant community within a reasonable period. The retrogression at this point can be reversed with relatively small labor and cost input if measures are taken soon enough. Application of prescribed grazing is essential to stop the decline of high quality midgrasses and forbs. Prescribed burning can be used in some rainfall areas to control small woody plants and their seedlings. These can also be controlled through individual plant treatment mechanically or with appropriate chemical application.

Figure 10. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 820 | 1200 | 1500 |

| Forb | 110 | 160 | 250 |

| Shrub/Vine | 120 | 160 | 200 |

| Tree | 50 | 80 | 130 |

| Total | 1100 | 1600 | 2080 |

Figure 11. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3255, Mid & Shortgrass Mesq. Savannah Comm.. Plant community dominated by midgrasses with some shortgrass influence. Increase of shrubs and trees onsite..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 5 | 4 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

With heavy abusive grazing, no brush management, brush invasion, and no fires, the Midgrass Savannah Community will shift to the Mid/Shortgrass Mesquite Savannah Community.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

With prescribed grazing, brush management, IPT, and prescribed burning, the Mid/Shortgrass Mesquite Savannah Community can be reverted back to the Midgrass Savannah Community.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 2

Shortgrass Savannah

Dominant plant species

-

mesquite (Prosopis), shrub

-

buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides), grass

-

curly-mesquite (Hilaria belangeri), grass

Community 2.1

Shortgrass Mesquite/Mixedbrush Savannah

This community represents a significant vegetation shift, crossing the threshold from the Savannah State to the Shortgrass Mesquite/Mixed Brush Savannah community. The major woody increaser species, primarily mesquite, have multiplied until they comprise up to 20 percent of the overstory canopy and exert strong influence on the site, with total grass production severely restricted. The reference community midgrasses are almost gone, grazed or shaded out, and short grasses are predominant. The Texas wintergrass population becomes significant. Palatable perennial forbs are scarce. The proportion of toxic plants increases; some of the more common include western bitterweed (Hymenoxys odorata), African rue (Peganum harmala) (an introduced invader species mostly associated with oilfield activity), paperflower (Psilostrophe cooperi), perennial broomweed (Amphiachyris spp.), peavine (Lathyrus spp.), and groundsel (Senecio spp.) species. This site exhibits mesquite up to 15 feet, as well as major increases in shrubs such as condalia, algerita, pricklyash (Zanthoxylum clava-herculis), redberry juniper (Juniperus pinchotti), and succulents like prickly pear (Opuntia spp.). Redberry juniper is an invader and will be more apparent when the site is in proximity to limestone hill or low stony hill ecological sites. Tarbush (Flourensia cernua) may invade from adjacent loamy ecological sites. Up to 60 percent of the ground is bare, which lends itself to a proliferation of annual forbs in some years, particularly when a wet fall/winter follows a dry spring/summer. Some, such as filaree (Erodium texanum) or redseed plantain (Plantago rhodosperma), provide a certain amount of high-quality forage for sheep, goats, and deer during winter and early spring, but quickly dry up when summer arrives. Litter is scarce and organic matter is low. Less water infiltrates and runoff increases. Topsoil loss through erosion accelerates, evidenced by plants on pedestals, rills, and stunted plant growth. Sheet erosion, though not easily detected visually, is high, particularly when the site is between a steep watershed and a draw or stream. If proper management is not planned and implemented, the site will continue to degrade and the community will shift toward a Mesquite/Mixed Brush Complex Community. By implementing conservation measures such as brush management (chemical, mechanical or, in specific cases, using biological species such as sheep and goats), range seeding (not recommended in areas of less than 18 inches annual rainfall), prescribed grazing and prescribed burning where appropriate, the land manager can possibly shift the community back toward a Midgrass Savannah community.

Figure 12. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 500 | 880 | 1200 |

| Tree | 300 | 320 | 400 |

| Forb | 180 | 240 | 300 |

| Shrub/Vine | 120 | 160 | 200 |

| Total | 1100 | 1600 | 2100 |

Figure 13. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3256, Shortgrass/Mesquite/Mixedbrush Savannah Comm.. Plant community characterized having more shrub and tree components as well as lesser shortgrass components..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

Community 3.1

Mesquite/Mixed Brush Complex

The Mesquite/Mixed Brush Complex is the result of an extreme shift of site characteristics from the original Midgrass Savannah Community. Mesquite and other woody increasers and invaders dominate, with canopy cover ranging from 20 percent upward. Their strong competition for water, sunlight and nutrients has severely limited or eliminated short grass populations, let alone the original midgrass community. Species such as hairy tridens (Erioneuron pilosum), red grama (Bouteloua trifida), Texas grama (Bouteloua rigidiseta), burrograss (Scleropogon brevifolius), various threeawns (Aristida spp.), tobosa, and annuals dominate the grass plant population of this site. If the woody population is primarily large mesquite trees, a significant amount of Texas wintergrass may develop, often in conjunction with prickly pear. The forb component consists predominantly of annuals or unpalatable perennials. More than 80 percent of the ground can be bare of grasses and forbs. Often most of the original, fertile topsoil has eroded away. Gullies may have formed. Bare soil has crusted and is relatively impermeable. However, under a heavy canopy of mesquite, juniper and/or mixed brush a buildup of leaf/needle litter occurs, which improves infiltration and helps retard erosion. This community very likely cannot be restored to the reference plant community. Decades of transition from a Midgrass Savannah Community (1.1) have negatively impacted soil properties, species diversity, site integrity, and hydrology features. However, the site can be reclaimed. Reclamation involving brush management with heavy equipment, aerial spraying, reseeding native grasses and forbs where rainfall is adequate, prescribed grazing, and reintroduction of fire through prescribed burning can restore the site to a semblance of its former self, but it will probably never completely reflect the original. It can, however, be maintained in a productive, stable state for grazing and, when native plants can be seeded and maintained, beneficial to wildlife.

Figure 14. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 9. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forb | 210 | 480 | 600 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 350 | 480 | 600 |

| Tree | 340 | 400 | 600 |

| Shrub/Vine | 200 | 240 | 300 |

| Total | 1100 | 1600 | 2100 |

Figure 15. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3257, Mesquite/Mixedbrush Complex Community. Dominated by mesquite and other woody species along with invaders. Canopy is over 20%. Competition for water, light and nutrients have severely limited shortgrass populations..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 5 | 5 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

State 4

Reclamation

Community 4.1

Open Grassland

This community is the product of endeavors to reclaim the Mesquite/Mixed Brush Complex or, less frequently, the Shortgrass Mesquite/Mixed Brush Savannah Community. Depending on the goals of the land user, reclamation efforts might involve the whole site or only part of it. A land manager involved primarily with livestock might prefer more open, grassy areas, whereas one interested mostly in wildlife would probably want to leave substantial brushy areas. Through brush management, reseeding of native species (both grasses and forbs) in areas of adequate rainfall, prescribed grazing and re-introduction of fire where appropriate, one can possibly manipulate this site successfully towards a reference community appearance, but it will never be able to mirror the original site. However, utilizing natives as the reseeding source will greatly benefit wildlife species such as deer, turkey, quail, and other birds. This Open Grassland Community may also be comprised of seeded species which are non-native and which may occur as a monoculture community. This type may contain less cover or food for wildlife, often practically devoid of native grasses and forbs. The annual production was taken from the variations of the plant species that are described in this plant community. The site’s capacity to produce must be determined over time under careful management. Maintenance through prescribed grazing, prescribed burning and individual plant treatment with appropriate chemicals can preserve the site’s sustained production indefinitely. Without these measures, the site will experience renewed encroachment of mesquite and other increasers/invaders.

Figure 16. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 10. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 1000 | 1600 | 2200 |

| Forb | 50 | 125 | 200 |

| Shrub/Vine | 50 | 75 | 100 |

| Tree | 50 | 75 | 100 |

| Total | 1150 | 1875 | 2600 |

Figure 17. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3258, Open Grassland Community. Primarily composed of reseeded grass and forb species that are adapted to this area. Some monocultures of non-native species may be used as well..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 5 | 4 |

Community 4.2

Open Grassland with Mesquite Encroachment

This community is a man-induced Open Grassland Community that has an encroachment of woody species. Through the re-introduction of prescribed burning, prescribed grazing, and individual plant treatment, this site can successfully be shifted back toward the Open Grassland Community and remain very productive. If these management alternatives are not implemented in a timely manner, this site will become reinfested with woody species. Over a period of years or possibly decades, it will again become heavily infested with brush and will have limited forage productivity, subsequently reverting to the Mesquite/Mixed Brush Complex.

Figure 18. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 11. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 820 | 1200 | 1500 |

| Forb | 110 | 160 | 250 |

| Shrub/Vine | 120 | 160 | 200 |

| Tree | 50 | 80 | 130 |

| Total | 1100 | 1600 | 2080 |

Figure 19. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3259, Open Grassland with Mesquite Encroachment Community. Man-induced open grassland community with mesquite encroachment. Management alternatives that were not implemented allowed brush to encroach the land..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 5 | 4 |

Pathway 4.1A

Community 4.1 to 4.2

With heavy abusive grazing, no brush management, brush invasion, no fires, and drought conditions, the Open Grassland Community will shift to the Open Grassland/Mesquite Encroachment Community.

Pathway 4.2A

Community 4.2 to 4.1

With prescribed grazing, brush management, IPT, and prescribed burning, the Open Grassland/Mesquite Encroachment Community will revert back to the Open Grassland Community.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

With heavy abusive grazing, no brush management, brush invasion, no fires, and drought conditions, the Midgrass Savannah State will transition to the Shortgrass Savannah State.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

With prescribed grazing, brush management, individual plant treatment (IPT), range planting, and prescribed burning conservation practices, the Shortgrass Savannah State can be reverted back to the Midgrass Savannah State.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting | |

| Planned Grazing System | |

| Native Plant Community Restoration and Management |

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

With heavy abusive grazing, no brush management, brush invasion, no fires, and drought conditions, the Shortgrass Savannah State will transition to the Mesquite Complex State.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

With heavy abusive grazing, no brush management, brush invasion, no fires, and drought conditions, the Mesquite Complex State can be transitioned to the Reclamation State.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 3

With heavy abusive grazing, no brush management, brush invasion, no fires, and drought conditions, the Reclamation State State will transition to the Mesquite Complex State.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting | |

| Planned Grazing System | |

| Native Plant Community Restoration and Management |

Additional community tables

Table 12. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Midgrasses | 420–910 | ||||

| cane bluestem | BOBA3 | Bothriochloa barbinodis | 420–910 | – | ||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 420–910 | – | ||

| silver beardgrass | BOLAT | Bothriochloa laguroides ssp. torreyana | 420–910 | – | ||

| Texas cupgrass | ERSE5 | Eriochloa sericea | 420–910 | – | ||

| 2 | Midgrasses | 180–390 | ||||

| Arizona cottontop | DICA8 | Digitaria californica | 180–390 | – | ||

| green sprangletop | LEDU | Leptochloa dubia | 180–390 | – | ||

| vine mesquite | PAOB | Panicum obtusum | 180–390 | – | ||

| plains bristlegrass | SEVU2 | Setaria vulpiseta | 180–390 | – | ||

| composite dropseed | SPCOC2 | Sporobolus compositus var. compositus | 180–390 | – | ||

| Drummond's dropseed | SPCOD3 | Sporobolus compositus var. drummondii | 180–390 | – | ||

| 3 | Shortgrasses | 120–260 | ||||

| buffalograss | BODA2 | Bouteloua dactyloides | 120–260 | – | ||

| curly-mesquite | HIBE | Hilaria belangeri | 120–260 | – | ||

| 4 | Cool Season grasses | 100–235 | ||||

| Canada wildrye | ELCA4 | Elymus canadensis | 100–235 | – | ||

| Texas wintergrass | NALE3 | Nassella leucotricha | 100–235 | – | ||

| 5 | Mid/Shortgrasses | 60–130 | ||||

| Wright's threeawn | ARPUW | Aristida purpurea var. wrightii | 60–130 | – | ||

| fall witchgrass | DICO6 | Digitaria cognata | 60–130 | – | ||

| Hall's panicgrass | PAHA | Panicum hallii | 60–130 | – | ||

| Reverchon's bristlegrass | SERE3 | Setaria reverchonii | 60–130 | – | ||

| white tridens | TRAL2 | Tridens albescens | 60–130 | – | ||

| slim tridens | TRMU | Tridens muticus | 60–130 | – | ||

| 6 | Shortgrass | 120–260 | ||||

| tobosagrass | PLMU3 | Pleuraphis mutica | 120–260 | – | ||

| 7 | Shortgrasses | 10–25 | ||||

| Grass, annual | 2GA | Grass, annual | 10–25 | – | ||

| Texas grama | BORI | Bouteloua rigidiseta | 10–25 | – | ||

| red grama | BOTR2 | Bouteloua trifida | 10–25 | – | ||

| hairy woollygrass | ERPI5 | Erioneuron pilosum | 10–25 | – | ||

| burrograss | SCBR2 | Scleropogon brevifolius | 10–25 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 8 | Forbs | 60–130 | ||||

| Indian mallow | ABUTI | Abutilon | 60–130 | – | ||

| angel's trumpets | ACLO2 | Acleisanthes longiflora | 60–130 | – | ||

| low silverbush | ARHU5 | Argythamnia humilis | 60–130 | – | ||

| white sagebrush | ARLUM2 | Artemisia ludoviciana ssp. mexicana | 60–130 | – | ||

| croton | CROTO | Croton | 60–130 | – | ||

| prairie clover | DALEA | Dalea | 60–130 | – | ||

| bundleflower | DESMA | Desmanthus | 60–130 | – | ||

| Engelmann's daisy | ENGEL | Engelmannia | 60–130 | – | ||

| beeblossom | GAURA | Gaura | 60–130 | – | ||

| Gregg's tube tongue | JUPI5 | Justicia pilosella | 60–130 | – | ||

| trailing krameria | KRLA | Krameria lanceolata | 60–130 | – | ||

| low menodora | MEHE2 | Menodora heterophylla | 60–130 | – | ||

| Nuttall's sensitive-briar | MINU6 | Mimosa nuttallii | 60–130 | – | ||

| upright prairie coneflower | RACO3 | Ratibida columnifera | 60–130 | – | ||

| wild petunia | RUELL | Ruellia | 60–130 | – | ||

| awnless bushsunflower | SICA7 | Simsia calva | 60–130 | – | ||

| fanpetals | SIDA | Sida | 60–130 | – | ||

| Texas nightshade | SOTR2 | Solanum triquetrum | 60–130 | – | ||

| globemallow | SPHAE | Sphaeralcea | 60–130 | – | ||

| noseburn | TRAGI | Tragia | 60–130 | – | ||

| vervain | VERBE | Verbena | 60–130 | – | ||

| 9 | Annual Forbs | 10–25 | ||||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 10–25 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 10 | Shrubs/Vines | 60–130 | ||||

| fourwing saltbush | ATCA2 | Atriplex canescens | 60–130 | – | ||

| snakewood | CONDA | Condalia | 60–130 | – | ||

| Christmas cactus | CYLE8 | Cylindropuntia leptocaulis | 60–130 | – | ||

| jointfir | EPHED | Ephedra | 60–130 | – | ||

| stretchberry | FOPU2 | Forestiera pubescens | 60–130 | – | ||

| desert-thorn | LYCIU | Lycium | 60–130 | – | ||

| algerita | MATR3 | Mahonia trifoliolata | 60–130 | – | ||

| pricklypear | OPUNT | Opuntia | 60–130 | – | ||

| littleleaf sumac | RHMI3 | Rhus microphylla | 60–130 | – | ||

| bully | SIDER2 | Sideroxylon | 60–130 | – | ||

| Texas Hercules' club | ZAHI2 | Zanthoxylum hirsutum | 60–130 | – | ||

| lotebush | ZIOB | Ziziphus obtusifolia | 60–130 | – | ||

|

Tree

|

||||||

| 11 | Trees | 60–130 | ||||

| netleaf hackberry | CELAR | Celtis laevigata var. reticulata | 60–130 | – | ||

| honey mesquite | PRGL2 | Prosopis glandulosa | 60–130 | – | ||

| live oak | QUVI | Quercus virginiana | 60–130 | – | ||

| western soapberry | SASAD | Sapindus saponaria var. drummondii | 60–130 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

This site is suitable to produce domestic livestock and to provide habitat for native wildlife. Cow-calf, stocker cattle, sheep, and goats can utilize this site. Carrying capacity has declined drastically over the past 100 years due to deterioration of the reference plant community. An assessment of vegetation is needed to determine the site’s current carrying capacity. Calculations used to determine livestock stocking rate should be based on forage production remaining after determining use by resident wildlife, then refined by frequent and careful observation of the plant community’s response to animal foraging.

A large diversity of wildlife is native to this site. In the historic plant community, migrating bison, grazing primarily during wetter periods, resident pronghorns and smaller populations of white-tailed deer, desert mule deer, quail, and prairie chickens were the more predominant species. With the subsequent transformation of the plant community, due primarily to the influence of man and climate change, the kind and proportion of wildlife species have been altered.

With the eradication of the screwworm fly, increase in woody vegetation and man-suppressed natural predation, deer numbers have increased and are often in excess of carrying capacity. Where deer numbers are excessive, overbrowsing and overuse of preferred forbs causes deterioration of the plant community. Progressive management of deer populations through hunting can keep populations in balance and provide an economically important ranching enterprise. Achieving a balance between brushy cover and more open plant communities on this and adjacent sites is important to deer management. Competition among deer, sheep, and goats must be a consideration in livestock and wildlife management to prevent damage to preferred vegetation.

Smaller mammals include many kinds of rodents, jackrabbit, cottontail rabbit, raccoon, skunks, possum, and armadillo. Mammalian predators include coyote, red fox, gray fox, bobcat, and mountain lion. Wolves were common in earlier times, bears resided in some areas, and an occasional jaguar was encountered. Many species of snakes and lizards are native to the site.

Many species of birds are found on this site including game birds, songbirds, and birds of prey. Major game birds that are economically important are bobwhite quail, scaled (blue) quail, and mourning dove. Quail prefer a combination of low shrubs, bunch grass (critical for nesting cover), bare ground, and low successional forbs. Turkeys visit the site to feed. The different species of songbirds vary in their habitat preferences. Habitat on this site that provides a large diversity of grasses, forbs, and shrubs will support a good variety and abundance of songbirds. Birds of prey are important to keep the numbers of rodents, rabbits, and snakes in balance.

Hydrological functions

The site is well drained with moderate water holding capacity. Light showers are ineffective on this site, with insufficient infiltration to benefit the deeper-rooted midgrasses. The reference community has a positive influence on the infiltration and percolation of rainfall to plant roots. Loss of vegetative cover, mulch and soil organic matter has a negative impact on infiltration, as does compaction due to overgrazing. More rainfall is directed to overland flow, which causes increased soil erosion and flooding. Slowly permeable to start with, soils become more prone to drought stress.

When heavy grazing or prolonged drought occurs, the water cycle becomes impaired due to the loss or reduction of bunchgrass and ground cover. Infiltration is decreased and runoff is increased due to poor ground cover, rainfall splash, soil capping, low organic matter, and poor structure. With a combination of a sparse ground cover and intensive rainfall, this site can contribute to increased frequency and severity of flooding within a watershed. Soil erosion is accelerated; quality of surface runoff is poor, and sedimentation is increased. Organic matter is lost from the site with surface runoff and decrease of herbaceous recycling.

As the site becomes dominated by woody species, the water cycle is further altered. Interception of rainfall by tree and shrub canopies increases, thereby reducing the amount of rainfall reaching the surface. However, stem flow is greater due to the funneling effect of the canopy, which increases soil moisture at the base of the tree and infiltration under the canopy is increased due to the mulch effect of leaf litter. Increased transpiration, especially by evergreen species such as live oak and juniper, accelerates depletion of soil moisture. As woody species increase, grass cover declines, which causes some of the same results as heavy grazing. Brush management combined with effective grazing management can help restore the natural hydrology of the site. Grass recovery, however, is slow.

Recreational uses

This site has the appeal of the wide-open spaces and a wide variety of plant and animal life. In good years it is blanketed by colorful spring flowers. The area is also used for hunting, birding, and other eco-tourism related enterprises.

Wood products

Honey mesquite can be used for firewood and the specialty wood industry.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information provided here has been derived from limited NRCS clipping data, and from field observations of range trained personnel.

Other references

Archer, S. 1994. Woody plant encroachment into southwestern grasslands and savannas: Rates, patterns, and proximate causes. Ecological implications of livestock herbivory in the West, 13-68.

Archer, S. and F. E. Smeins. 1991. Ecosystem-level processes. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heischmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Bestelmeyer, B. T., J. R. Brown, K. M. Havstad, R. Alexander, G. Chavez, and J. E. Herrick. 2003. Development and use of state-and-transition models for rangelands. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):114-126.

Bracht, V. 1931. Texas in 1848. German-Texan Heritage Society, Department of Modern Languages, Southwest Texas State University, San Marcos, TX.

Bray, W. L. 1904. The timber of the Edwards Plateau of Texas: Its relations to climate, water supply, and soil. No. 49. US Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Forestry.

Briske, D. D., S. D. Fuhlendorf, and F. E. Smeins. 2005. State-and-transition models, thresholds, and rangeland health: A synthesis of ecological concepts and perspectives. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 58(1):1-10.

Brothers, A., M. E. Ray Jr., and C. McTee. 1998. Producing quality whitetails, revised edition. Texas Wildlife Association, San Antonio, TX.

Brown, J. K. and J. K. Smith. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems, effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 257:42.

Davis, W. B. 1974. The Mammals of Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 41.

Foster, J. H. 1917. The spread of timbered areas in central Texas. Journal of Forestry 15(4):442-445.

Frost, C. C. 1998. Presettlement fire frequency regimes of the United States: A first approximation. Fire in ecosystem management: Shifting the paradigm from suppression to prescription. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 20:70-81.

Gould, F. W. 1975. The grasses of Texas. The Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Hatch, S. L. and J. Pluhar. 1993. Texas Range Plants. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Hamilton, W. and D. Ueckert. 2005. Rangeland woody plant control--past, present, and future. Texas A&M University Press. College Station, TX.

Hart, C. R., A. McGinty, and B. B. Carpenter. 1998. Toxic plants handbook: Integrated management strategies for West Texas. Texas Agricultural Extension Service, The Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

Heitschmidt, R. K. and J. W. Stuth. 1991. Grazing management: An ecological perspective. Timberline Press, Portland, OR.

Loughmiller, C. and L. Loughmiller. 1984. Texas wildflowers. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Milchunas, D. G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 126:169.

Niehaus, T. F. 1998. A field guide to Southwestern and Texas wildflowers (Vol. 31). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, MA.

Ramsey, C. W. 1970. Texotics. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, TX.

Roemer, F. translated by O. Mueller. 1995. Roemer’s Texas, 1845 to 1847. Texas Wildlife Association, San Antonio, TX.

Scifres, C. J. and W. T. Hamilton. 1993. Prescribed burning for brushland management: The South Texas example. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX.

Smeins, F. E., S. Fuhlendorf, and C. Taylor, Jr. 1997. Environmental and land use changes: A long term perspective. Juniper Symposium, 1-21.

Taylor, C. A. and F. E. Smeins. 1994. A history of land use of the Edwards Plateau and its effect on the native vegetation. Juniper Symposium, 94:2.

Thurow, T. L. 1991. Hydrology and erosion. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heitschmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Tull, D. and G. O. Miller. 1991. A field guide to wildflowers, trees and shrubs of Texas. Texas Monthly Publishing, Houston, TX.

USDA-NRCS. 1997. National range and pasture handbook. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture. Natural Resources Conservation Service, Grazing Lands Technology Institute.

Weniger, D. 1997. The explorers’ Texas: The animals they found. Eakin Press, Austin, TX.

Weniger, D. 1984. The explorers’ Texas: The lands and waters. Eakin Press, Austin, TX.

Vines, R. A. 1984. Trees of Central Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Vines, R. A. 1960. Trees, shrubs and vines of the Southwest. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Contributors

Bruce Deere

Edits by Travis Waiser, MLRA Leader, NRCS, Kerrville, TX

Approval

Bryan Christensen, 9/19/2023

Acknowledgments

The following individuals assisted with the development of this site description:

Gary Askins, DC, NRCS, Big Lake, TX

Dr. Dean Chamrad, RMS, Retired NRCS, San Angelo, TX

Rusty Dowell, SS, NRCS, San Angelo, TX

Dr. Charles R. Hart, RMS, Agrilife, Pecos, TX

Dr. Jake Landers, RMS, Retired Agrilife, San Angelo, TX

Dr. Allan McGinty, RMS, Agrilife, San Angelo, TX

Ken Moore, RMS, UT Lands, Big Lake, TX

Steve Nelle, Biologist, NRCS, San Angelo, TX

Rudy Pederson, RMS, Retired NRCS, San Angelo, TX

Darrel Seidel, DC, NRCS, Sanderson, TX

Dr. Bob Steger, Consultant, Mertzon, TX

Dr. Charles Taylor, Director, Sonora Experiment Station, Sonora, TX

Dr. Darrell Ueckert, RMS, Agrilife, San Angelo, TX

Terry Whigham, DC, NRCS, Fort Stockton, TX

Stephen Zuberbueler, DC, NRCS, Ozona, TX

QC/QA completed by:

Bryan Christensen, SRESS, NRCS, Temple, TX

Erin Hourihan, ESDQS, NRCS, Temple, TX

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Joe Franklin, RMS, NRCS, San Angelo, TX |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | (325) 944-0147 |

| Date | 10/05/2011 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

None to slight. Site may receive runoff from adjacent sites. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

None to slight. Minimal pedestals or terracettes due to erosion. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Less than 10 percent bare ground. Small and non-connected areas. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

None. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Minimal movement of fine litter for short distances. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Erosion stability values estimated at 5 to 6. Water erosion hazard of soil is slight. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

Angelo soil is grayish brown clay loam to 8 inches and brown clay loam in 8 to 14 inch depth. The surface layer is weak fine granular and subangular blocky. Many fine roots and worm casts. SOM: High -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

The reference community provides good plant distribution and soil cover with excellent infiltration. Under normal rainfall, runoff is small and clear. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm season midgrassSub-dominant:

Warm season midgrass forbOther:

cool season grasses shrub/vine treesAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Minimal. Grasses will almost always show some mortality and decadence, especially under drought conditions. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Interspaces between plant canopys essentially covered with various sizes of litter and mulch. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

1,100 pounds per acre in years with below average moisture, 1,600 pounds per acre in average and 2,100 pounds per acre in above average moisture years. Site may receive extra moisture from upslope sites and be highly productive in wet years. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Mesquite, pricklypear, juniper, broom snakeweed, agarito, acacia, condalia, and annual brooweed. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Good. All species should be capable of reproducing except during periods of prolonged drought, heavy natural herbivory or intense fire. Recovery from these disturbances will take 2 to 5 years.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of natural disturbance regimes |

| T2A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, coupled with drought conditions |

| T3A | - | Removal of woody canopy followed by rangeland seeding |

| T4A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time coupled with excessive grazing pressure |