Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R081BY333TX

Loamy 19-23 PZ

Last updated: 9/19/2023

Accessed: 03/14/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

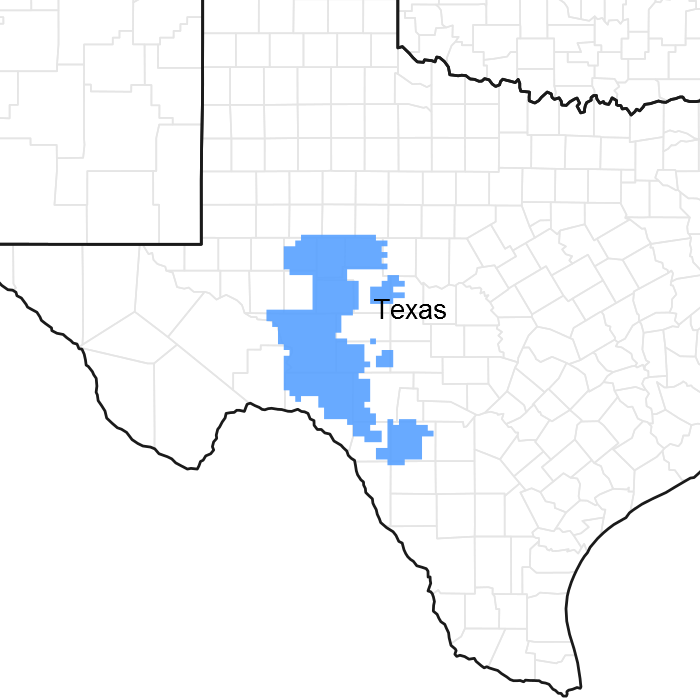

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 081B–Edwards Plateau, Central Part

This area is entirely in south-central Texas. It makes up about 11,125 square miles (28,825 square kilometers). The towns of Fredericksburg, Junction, Menard, Rocksprings, and Sonora are in this MLRA. Interstate 10 crosses the middle part of the area. A few State parks and State historic sites are in this MLRA.

Classification relationships

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006.

-Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 81B

Ecological site concept

The Loamy Ecological Site occurs on uplands with deep soils. The soils are loamy textured with typically less than 35 percent clay.

Associated sites

| R081BY342TX |

Shallow 19-23 PZ Often adjacent and uphill. Soils have <20” depth over limestone, much less production. |

|---|---|

| R081BY353TX |

Very Shallow 19-23 PZ Often adjacent and uphill. Soils <10” depth over limestone, much less production. |

Similar sites

| R081BY325TX |

Clay Loam 19-23 PZ Often adjacent and downhill. Soils have higher clay content. |

|---|---|

| R081BY334TX |

Loamy Bottomland 19-23 PZ The Loamy Bottomland site can be flooded. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Bouteloua curtipendula |

Physiographic features

The Loamy ecological sites are located on nearly level and gently sloping convex surfaces. These soils are on broad lower side slopes of valleys, side slopes of draws, intermittent streams, or playas mainly in the Edwards Plateau of Texas. Slopes range from 0 to 5 percent. Runoff is negligible to low. These soils have developed in calcareous loamy sediments presumed to be alluvial and eolian in origin and were re-calcified by atmospheric dust.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Plateau

> Plain

(2) Plateau > Stream terrace (3) Plateau > Ridge |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to low |

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 564 – 838 m |

| Slope | 0 – 5% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate in the MLRA 81B is subtropical subhumid on the eastern portion and subtropical steppe on the western portion of the MLRA. Winters are dry, and the summers are hot and humid. The precipitation increases from west to east and the temperatures increase from north to south. The area usually receives 65 to 70 percent sunshine each year. The majority of the rainfall occurs during the warm months of April to October. Most precipitation comes from thunderstorms that vary in the amount of water received and the areas covered. Spring is characterized by fluctuating patterns, but mild temperatures prevail. July and August are relatively dry and hot with little weather variability day-to-day. As summer progresses through fall, an increase of precipitation usually occurs in the eastern portions while a decrease of precipitation occurs to the west. Winter temperatures are mild, but polar Canadian air masses bring rapid drops in temperature. These cold spells last 2 or 3 days. Prevailing winds are southerly with March and April the windiest months.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 210-240 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 240-280 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 483-610 mm |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 210-240 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 240-280 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 483-635 mm |

| Frost-free period (average) | 225 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 260 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 559 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) OZONA [USC00416734], Ozona, TX

-

(2) BIG LAKE 2 [USC00410779], Big Lake, TX

-

(3) CARTA VALLEY [USC00411492], Rocksprings, TX

-

(4) ELDORADO [USC00412809], Eldorado, TX

-

(5) SONORA [USC00418449], Sonora, TX

Influencing water features

Sites are on uplands and not affected by streams or wetlands.

Wetland description

N/A

Soil features

The soils consist of deep and very deep, well drained, moderately permeable soils formed in loamy calcareous sediments. The soil series correlated to this site include: Broome and Reagan.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

–

limestone

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Silty clay loam (2) Silt loam (3) Clay loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Fine-silty |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow to moderate |

| Soil depth | 152 – 203 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 5% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

10.41 – 17.02 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

2 – 25% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

7.9 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (10.2-101.6cm) |

0 – 6% |

Ecological dynamics

The Loamy Ecological Site dynamics included pre-settlement influences included grazing or browsing by endemic pronghorn antelope, deer, and migratory bison, severe droughts, and frequent fires. Wildfires occurred at frequent intervals maintaining woody species at less than five percent canopy. The frequent fires favored grasses over woody plants and forbs, but there were a variety of forbs present. Sideoats grama, vine-mesquite, and cane bluestem are thought to be the dominant grasses on the site before European settlement, contributing as much as 35 percent of the plant annual production. Slim tridens, sand dropseed, threeawns, and buffalograss were common shortgrasses. Various shrubs and forbs were scattered throughout the site.

The Midgrass Prairie Community (1.1) was relatively stable and resilient within the climate, soil and fire regime until the advent of animal husbandry and fencing in the mid to late 1800’s. Not understanding the limits of rangeland productivity, European settlers, and the ranchers that followed, universally overstocked the area with domestic livestock. As overgrazing occurred, there was a reduction of the more palatable grasses and forbs, a decline in biomass, ground cover, and organic matter. The decline in plant matter and efforts by man induced a reduction in frequency and intensity of fires. The shift in plant cover and decline in soil properties favored woody plant encroachment. The woody and herbaceous invaders were generally endemic species released from competition and suppression by fire. In the Mixed-grass Prairie Community (1.2) which followed, the more palatable grasses and forbs gave way to less palatable or more grazing resistant midgrasses, shortgrasses, and forbs. Midgrasses, especially sideoats grama and the bluestems, still dominated annual herbage production, but the encroaching woody species increased in production.

When the Mixed-grass Prairie Community (1.2) is continually overgrazed and fire is excluded, ecological succession transitions the plant community into one that is dominated by woody plants. More grazing resistant grasses such as vine-mesquite, tobosa, buffalograss, and less palatable forbs begin replacing the midgrasses. As the midgrass cover declines, litter, mulch, and soil organic matter decline while bare ground, erosion, and other desertification processes increase. The microclimate in the grassland areas becomes more arid. Increasing woody dominants are primarily mesquite, tasajillo, and broom snakeweed. Rest from grazing and/or prescribed burning will generally not restore the grassland community when the woody plant community exceeds 15 percent canopy on this site and/or the plants reach fire-resistant age (greater than two years) and/or size (about four feet in height). At this threshold, the site transitions into a new plant community: a Shortgrass/Mixed-brush Community (2.1). This threshold also marks the beginning of a new state, the Woodland State (2).

Mesquite, acacias, lotebush, and sometimes redberry juniper dominate the Shortgrass/Mixed-brush Community (2.1). Mesquite is often limited by high calcareous soil conditions. The grass component is a mixture of low palatability midgrasses, shortgrasses, and low-quality forbs. With continued livestock overgrazing, high-quality midgrasses are replaced by grazing resistant species, such as tobosa, burrograss, buffalograss, sand dropseed, three-awns, and western ragweed. Sideoats grama often persists because of the high calcium content of the soils. During this stage, the process of retrogression can be reversed with relatively inexpensive brush control practices such as individual plant treatments, proper stocking, and prescribed grazing management that allow the application of prescribed burning. If these practices are not applied and overgrazing continues, the woody canopy will continue to increase in dominance and the plant community transitions into a Mixed–brush/Shortgrass/Annuals Community (2.2). Once the brush canopy exceeds 35 percent, annual production for the understory becomes limited and is generally made up of unpalatable shrubs, grasses, and forbs. Brushy species such as mesquite, pricklypear, lotebush, acacia, and tarbush form thickets. Shortgrasses, especially tobosa, burrograss, threeawns, and tridens persist in the interspaces. Texas wintergrass and annual forbs are abundant in years of excessive moisture.

Until maximum ground cover by woody species is reached, erosion continues in the interspaces and runoff can be excessive. Considerable litter and soil movement occur from exposed soil during heavy rains. The exposed soil crusts readily, creating an opportunity for further soil and wind erosion. The microclimate becomes drier as interception losses increase with canopy cover. Once woody canopy cover reaches potential, however, the hydrologic processes, energy flow, and nutrient cycling stabilize under the shrubland environment.

High cost and high energy management practices are required to restore the Mixed-Brush/Shortgrass/Annuals Community (2.2) back to the Grassland State (1). Generally, mechanical or herbicidal brush management practices such as aerial spraying, dozing, and/or individual plant treatments (IPT) along with other conservation practices such as range planting, grazing deferment, prescribed grazing, and prescribed burning are necessary for the ecological site to return to a grassland community.

The Loamy site is used primarily as range. The soils on the flatter areas are arable and sometimes cultivated. The site is moderately erodible and should be cultivated with care, if at all. Most fields previously cultivated for crops have been returned to native or introduced grass species. Even if re-vegetated to introduced grasses, most are managed as rangeland.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, may be coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Extensive soil disturbance followed by seeding |

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of historic disturbance return intervals |

| T2A | - | Extensive soil disturbance followed by seeding |

| T3A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, may be coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Grassland

Dominant plant species

-

sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), grass

-

cane bluestem (Bothriochloa barbinodis), grass

Community 1.1

Midgrass Prairie

Figure 8. 1.1 Midgrass Prairie Community

The Midgrass Prairie Community (1.1) is the interpretive plant community for the Loamy Ecological Site. It developed under a dry, sub-humid climate with hot dry summers and mild winters. Herbivory by migrating bison, indigenous antelope and deer influenced the plant composition and structure, but not as much as frequent and intense wildfires, which kept woody species in check. Vine ephedra, four-wing saltbush, tarbush, cholla, and catclaw acacia are typical but infrequent, shrubs. Sideoats grama is the dominant or co-dominant grass throughout the site. Also occurring on the site, but in smaller amounts, are cane bluestem, silver bluestem, vine-mesquite, plains bristlegrass, and Arizona cottontop. Blue grama, black grama, tobosa, burrograss, and buffalograss are common shortgrasses. Forbs include gaura, broom snakeweed, mallow, ratany, sida, dalea, and leather-weed croton. The Midgrass Prairie Community (1.1) produced from 800 to 2,500 pounds of biomass annually, depending upon the soils and the amount of precipitation. Grasses make up as much as 90 percent of the annual production. A good cover of grasses and mulch aide in the infiltration of rainfall into the moderately permeable soil and reduced runoff. Little runoff occurs in reference condition.

Figure 9. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 835 | 1877 | 2606 |

| Forb | 45 | 101 | 140 |

| Shrub/Vine | 17 | 39 | 56 |

| Tree | – | – | 1 |

| Total | 897 | 2017 | 2803 |

Figure 10. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3637, Midgrass Prairie Community. Warm-season grassland dominated by midgrasses with few forbs and shrubs..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

Community 1.2

Mixed-grass Prairie

Figure 11. 1.2 Mixed-grass Prairie Community

The Mixed-grass Prairie Community (1.2) is the result of overgrazing by livestock for a long period of time. Drought is a contributing factor. It is a midgrass and shortgrass dominated grassland being encroached by indigenous or invading woody species that had been held at low densities by repeated fires and competition from a vigorous grass component. The reference condition grasses and forbs are being replaced by the more grazing resistant midgrasses and shortgrasses. Numerous brushy species, including mesquite, lotebush, and tasajillo, are increasing because overgrazing by livestock has reduced grass cover, exposed more soil, and reduced fine fuel for fire. In this plant community, the increasing woody species are generally less than four feet tall and still subject to control by fire and improved grazing management. The woody canopy varies between 5 and 15 percent depending on severity of grazing, time since burned and availability of invading species. Typically, mesquite, broom snakeweed, and western ragweed increase in density. Broom snakeweed is cyclic, depending somewhat on rainfall. Less preferred brushy species such as littleleaf sumac, lotebush, wolfberry, four-winged saltbush, and catclaw acacia also increase. Important grasses are sideoats grama, vine mesquite, cane bluestem, silver bluestem, and Texas wintergrass. Most of the reference perennial forbs exist. With continued overgrazing sideoats grama, blue grama, black grama, cupgrass and vine-mesquite give way to tobosa, buffalograss, burrograss, and less palatable forbs. Annual primary production ranges from 600 to 2,200 pounds per acre and is still predominantly grass. Heavy abusive grazing has reduced plant cover, litter and mulch resulting with increased bare ground slightly exposing the soil to some erosion. There could be some mulch and litter movement during rainstorms’ but due to gentle slopes and soil condition little soil movement would take place in this vegetation type.

Figure 12. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 538 | 1345 | 1973 |

| Shrub/Vine | 101 | 252 | 370 |

| Forb | 34 | 84 | 123 |

| Tree | – | – | – |

| Total | 673 | 1681 | 2466 |

Figure 13. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3615, Midgrass Dominant with Shortgrass and Scattered Shrubs. Midgrass dominant vegetation with shortgrasses and scattered shrubs..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 13 | 23 | 15 | 4 | 5 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 3 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

The Midgrass Prairie Community (1.1) furnishes good habitat for grazing type wildlife such as bison and pronghorn antelope and, in recent times, cattle. Most areas of the site receive extra grazing and are often abused unless good prescribed grazing is practiced. This plant type is resilient and recovers well under good grazing management. However, with overgrazing, decrease in intensity and frequency of fires and no brush management, this plant community transitions into a Mixed-grass Prairie Community (1.2).

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Once the Shortgrass/Mixed-brush vegetation type occurs, normal range management practices, such as proper grazing and prescribed burning, cannot reverse the trend to woody plant dominance. Brush control practices, such as individual plant treatment and prescribed burning, are necessary to maintain this vegetation type or to return the community back to grassland.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 2

Woodland

Dominant plant species

-

pricklypear (Opuntia), shrub

-

lotebush (Ziziphus obtusifolia), shrub

-

sumac (Rhus), shrub

Community 2.1

Shortgrass/Mixed-brush

Figure 14. 2.1 Shortgrass/Mixed-brush Community

The Shortgrass/Mixed-brush Community (2.1) supports a 15 percent or greater woody plant canopy of mixed-brush. It is the result of selective overgrazing by livestock and deer and the differential response of plants to defoliation over a long period of time. There is a continued decline in diversity of the grassland component, and an increase in woody species and unpalatable forbs. Annual herbage production is reduced due to decline in soil structure and organic matter resulting in the compositional shift toward the non-grass components. All, except the more palatable woody species, have increased in size and density. Many of the reference shrubs are present. Typically, pricklypear, lotebush, littleleaf sumac, and broom snakeweed are common. Remnants of reference grasses and forbs are present, while unpalatable invaders occupy the interspaces between trees and shrubs. Buffalograss and blue grama are persistent increasers initially, but then give way to more tobosa and burrograss. Cool-season grasses, such as Texas wintergrass, plus other grazing resistant reference species, can be found under and around woody plants. Because of grazing pressure and competition for nutrients and water from the woody plants the grassland component shows a general lack of plant vigor and productivity. Other common shortgrasses include tridens, three-awns, sand dropseed, and sand muhly. As the grassland vegetation declines, more soil is exposed leading to erosion. Higher interception losses by the increasing woody canopy combined with evaporation and runoff can reduce the effectiveness of rainfall. Although soil conditions improve under the woody plant cover, soil organic matter and soil structure decline within the interspaces. Some soil loss can occur during heavy rainfall events. Total plant production declines somewhat, being approximately 600 to 2,300 pounds per acre, depending on precipitation. Annual production is balanced between herbaceous plants and woody plants. Browsing animals, like goats and deer, can find fair food value if twig plants have not been grazed excessively. Forage quantity and quality for cattle are low. Unless brush management and good grazing management are applied at this stage, the transition toward the Mixed-Brush/Shortgrass/Annuals Community (2.2) will continue. The trend cannot be reversed with good grazing management alone.

Figure 15. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 437 | 1166 | 1676 |

| Shrub/Vine | 157 | 426 | 611 |

| Forb | 67 | 179 | 258 |

| Tree | 11 | 22 | 34 |

| Total | 672 | 1793 | 2579 |

Figure 16. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3629, Shortgrass-Mixedbrush Community. Shortgrass and mixed-brush summer growth with some cool-season grass growth..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 3 | 3 | 7 | 13 | 20 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

Community 2.2

Mixed-brush/Shortgrass/Annuals

Figure 17. 2.2 Mixed-brush/Shortgrass/Annuals Community

The Mixed-brush/Shortgrass/Annuals Community (2.2) is the culmination of many years of overgrazing, lack of periodic fires, drought, and little brush management. Mesquite dominates this site, which can become a dense shrubland. Common shrubs are mesquite, pricklypear, broom snakeweed, lotebush, yucca, and tarbush. With continued heavy grazing and no brush control, the trees and shrubs can approach 60 percent ground cover and produce 75 percent of the forage. Shortgrasses and low-quality annual or perennial forbs occupy the woody plant interspaces. Characteristic grasses are burrograss, tobosa, buffalograss, sand dropseed, and three-awns. Texas wintergrass and cool-season annuals are found in and around tree/shrub cover. Grasses and forbs make up 30 percent or less of the annual herbage production. Forbs commonly found in this community include western ragweed, croton, mealycup sage, verbena, blueweed salvia, groundsels, gray goldaster, Louisiana sagewort, and lyreleaf greeneyes. Annual forbs can be abundant during high rainfall years. As the shrub canopy increases it acts to intercept rainfall and increase evapotranspiration losses, creating a more xeric microclimate initially. Soil fauna and organic mulch are reduced exposing more soil surface to erosion in the interspaces. The exposed soil crusts and erodes readily. However, within the woody canopy hydrologic processes stabilize, white soil organic matter and mulch begin to increase and eventually stabilize under the shrub canopy. The Mixed-brush/Shortgrass/Annuals Community provides good cover for wildlife, but only limited preferred forage or twigs are available for livestock or wildlife. Alternatives for restoration include brush control and range planting to return the shrubland to grassland. Proper stocking, prescribed grazing, and prescribed burning would then be necessary to maintain the desired community.

Figure 18. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 488 | 1311 | 1973 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 135 | 359 | 538 |

| Forb | 34 | 90 | 135 |

| Tree | 17 | 34 | 45 |

| Total | 674 | 1794 | 2691 |

Figure 19. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3618, Mixedbrush/Shortgrass Community. Yearlong green forage due to shrubs and cool season species growth in winter and spring. Peak rainfall period from April through September provides most productivity during summer growing season..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 5 | 7 | 8 | 14 | 18 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 7 | 4 |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Heavy abusive grazing, no fires, and no brush management would lead to a shift from the Shortgrass/Mixed-brush Community to the Mixed-brush/Shortgrass/Annuals Community.

Community 3.1

Converted Land

Soils of the Loamy Ecological Site are used mainly as range, but a few areas have been changed to the Converted Land Community (3.1). Wheat and grain sorghum are the main crops. When cropping is abandoned, the site should be re-vegetated with adapted native plant mixtures, which include reference condition species. Cultivation and erosion may have reduced soil productivity but near reference forage production may be obtained with a native plant mix. Introduced species often require more care but can also be productive as pasture. In any case, brush management is required to prevent brush invasion from adjacent areas. If fields are abandoned and left to revegetate naturally, weedy grasses, forbs, and shrubs will be the first species in secondary succession. They often persist for many years. Even without grazing, woody species will encroach and eventually dominate unless brush management practices and prescribed burning are applied.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Unless proper grazing and prescribed burning are initiated at this stage, the woody species continue to increase in size and density. When the woody plants become dense enough to suppress grass growth and resist fire damage (about 15 percent), a threshold in ecological succession is reached. The Mixed-grass Prairie Community (1.2) becomes a Shortgrass/Mixed-brush Community (2.1).

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

With crop cultivation and plowing, the Grassland State can convert into the Converted Land State.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Brush management, range planting, prescribed grazing, IPT, and prescribed burning are several conservation practices that can contribute to the Woodland State shift back to the Grassland State.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Range Planting | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Crop Cultivation and plowing can shift the Woodland State into the Converted Land State.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

Abandonment, no brush management, heavy abusive grazing, and no fires would revert the Converted Land State back to the Woodland State.

Additional community tables

Table 9. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Midgrasses | 336–1121 | ||||

| cane bluestem | BOBA3 | Bothriochloa barbinodis | 78–308 | – | ||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 78–308 | – | ||

| silver beardgrass | BOLAT | Bothriochloa laguroides ssp. torreyana | 78–308 | – | ||

| vine mesquite | PAOB | Panicum obtusum | 78–308 | – | ||

| 2 | Midgrasses | 168–560 | ||||

| Arizona cottontop | DICA8 | Digitaria californica | 39–168 | – | ||

| Texas cupgrass | ERSE5 | Eriochloa sericea | 39–168 | – | ||

| large-spike bristlegrass | SEMA5 | Setaria macrostachya | 39–168 | – | ||

| Reverchon's bristlegrass | SERE3 | Setaria reverchonii | 39–168 | – | ||

| 3 | Shortgrasses | 135–426 | ||||

| buffalograss | BODA2 | Bouteloua dactyloides | 45–78 | – | ||

| black grama | BOER4 | Bouteloua eriopoda | 17–45 | – | ||

| blue grama | BOGR2 | Bouteloua gracilis | 17–45 | – | ||

| fall witchgrass | DICO6 | Digitaria cognata | 17–45 | – | ||

| sand muhly | MUAR2 | Muhlenbergia arenicola | 17–45 | – | ||

| muhly | MUHLE | Muhlenbergia | 17–45 | – | ||

| Hall's panicgrass | PAHA | Panicum hallii | 17–45 | – | ||

| sand dropseed | SPCR | Sporobolus cryptandrus | 17–45 | – | ||

| tridens | TRIDE | Tridens | 17–45 | – | ||

| threeawn | ARIST | Aristida | 17–45 | – | ||

| 4 | Shortgrasses | 84–258 | ||||

| tobosagrass | PLMU3 | Pleuraphis mutica | 56–202 | – | ||

| burrograss | SCBR2 | Scleropogon brevifolius | 28–101 | – | ||

| 5 | Cool-season grasses | 67–207 | ||||

| Texas wintergrass | NALE3 | Nassella leucotricha | 67–207 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 6 | Forbs | 45–140 | ||||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 3–13 | – | ||

| aster | ASTER | Aster | 3–13 | – | ||

| lyreleaf greeneyes | BELY | Berlandiera lyrata | 3–13 | – | ||

| leather flower | CLEMA | Clematis | 3–13 | – | ||

| croton | CROTO | Croton | 3–13 | – | ||

| prairie clover | DALEA | Dalea | 3–13 | – | ||

| beeblossom | GAURA | Gaura | 3–13 | – | ||

| hoary false goldenaster | HECA8 | Heterotheca canescens | 3–13 | – | ||

| ratany | KRAME | Krameria | 3–13 | – | ||

| evening primrose | OENOT | Oenothera | 3–13 | – | ||

| sage | SALVI | Salvia | 3–13 | – | ||

| globemallow | SPHAE | Sphaeralcea | 3–13 | – | ||

| vervain | VERBE | Verbena | 3–13 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 7 | Shrubs/Vines | 17–56 | ||||

| acacia | ACACI | Acacia | 3–11 | – | ||

| fourwing saltbush | ATCA2 | Atriplex canescens | 3–11 | – | ||

| tree cholla | CYIMI | Cylindropuntia imbricata var. imbricata | 3–11 | – | ||

| prairie clover | DALEA | Dalea | 3–11 | – | ||

| jointfir | EPHED | Ephedra | 3–11 | – | ||

| American tarwort | FLCE | Flourensia cernua | 3–11 | – | ||

| desert-thorn | LYCIU | Lycium | 3–11 | – | ||

| algerita | MATR3 | Mahonia trifoliolata | 3–11 | – | ||

| pricklypear | OPUNT | Opuntia | 3–11 | – | ||

| mesquite | PROSO | Prosopis | 3–11 | – | ||

| sumac | RHUS | Rhus | 3–11 | – | ||

| yucca | YUCCA | Yucca | 3–11 | – | ||

| lotebush | ZIOB | Ziziphus obtusifolia | 3–11 | – | ||

|

Tree

|

||||||

| 8 | Trees | 0–1 | ||||

| hackberry | CELTI | Celtis | 0–1 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Many types of grassland insects, reptiles, birds, and mammals use the Loamy Ecological Site, either as their base habitat or from the adjacent sites. Historically, large animals included pronghorn antelope, white-tailed deer, mule deer, and bison. Small mammals include many kinds of rodents, jackrabbit, cottontail rabbit, raccoon, skunk, opossum, and armadillo. Predators include coyote, red fox, gray fox, bobcat and occasionally mountain lion. Game birds, songbirds, and birds of prey were indigenous or frequent users. Most of the animals from the past are still plentiful, but unfortunately, the antelope are found only in small numbers and bison have been extirpated. White-tailed deer and mule deer utilize the Loamy site in its various states. Deer, turkey, and quail particularly favor the habitat provided by the Mixed-grass Prairie Community (1.2) and Shortgrass/Mixed-brush Community (2.1). Deer, turkey, quail, and dove hunting is an important sport, or commercial enterprise, providing considerable income to landowners.

The site in reference conditions was very suited to primary grass eaters such as bison, pronghorn antelope and cattle. As retrogression occurs, and woody plants invade, it becomes better habitat for sheep, goats, deer, and other wildlife because of the browse and cool-season grasses. Predators, however, may preclude sheep and goats. While keeping deer competition in mind, livestock should be stocked in proportion to the available grass, forb, and browse forage. If the animal numbers are not kept in balance through grazing management and good wildlife population management, the late Mixed-Brush/Shortgrass/Annuals Community (2.2) will have little to offer as habitat except cover.

Hydrological functions

The Loamy Ecological Site is found on deep, nearly level to gently sloping soils of uplands. The soils are well drained and runoff is medium. Permeability is moderate and water holding capacity is high. Water and wind erosion hazard is slight to moderate. However, soil crusting can cause erosion from bare ground on steeper slopes if plant cover is removed.

Under reference conditions, the grassland vegetation intercepted and utilized much of the incoming rainfall in the soil solum. Only during extended rains or heavy thunderstorms was there much runoff. Litter and soil movement was slight. Standing plant cover, duff and organic matter decrease and surface runoff increases as the Midgrass Prairie Community (1.1) transitions to the Mixed-grass Prairie Community (1.2). Infiltration and percolation become limited as vegetative cover decreases. Evaporation and interception losses are higher, resulting in less moisture reaching the soil. Moisture seldom penetrates the soil profile due to low rainfall. These processes continue in the interstitial spaces in the Shortgrass/Mixed-brush Community (2.1).

If overgrazing continues, the plant community deteriorates further, and desertification processes continue. Herbaceous biomass production is reduced relative to reference conditions and production shifts from dominant grasses to primarily woody plants. The deeper-rooted woody plants are able to extract water from greater depths than the short grasses, so less water will be available for downslope movement. The woody plants compete for moisture with the remaining grasses and forbs further reducing production and ground cover in openings. Decreased litter and more bare ground allow erosion from soils in openings between shrubs. Once the Mixed-brush/Shortgrass/Annuals Community (2.2) canopy surpasses 60 percent, the hydrologic and ecological processes of nutrient cycling and energy flow will stabilize and be characteristic of shrubland processes.

Recreational uses

The Loamy site occurs in irregular or elongated bands with Clay Loam, Shallow and/or Very Shallow sites. Together, these sites are well suited for many outdoor recreational uses including hunting, hiking, camping, horse riding, and bird watching. The Loamy site, along with adjacent uplands, provides diverse scenic beauty and opportunities for equestrian activities.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented was derived from literature, limited NRCS clipping data (417s), field observations, and personal contacts with range-trained personnel.

Other references

Archer, S. 1994. Woody plant encroachment into southwestern grasslands and savannas: Rates, patterns, and proximate causes. Ecological implications of livestock herbivory in the West, 13-68.

Archer, S. and F. E. Smeins. 1991. Ecosystem-level processes. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heischmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Bestelmeyer, B. T., J. R. Brown, K. M. Havstad, R. Alexander, G. Chavez, and J. E. Herrick. 2003. Development and use of state-and-transition models for rangelands. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):114-126.

Bracht, V. 1931. Texas in 1848. German-Texan Heritage Society, Department of Modern Languages, Southwest Texas State University, San Marcos, TX.

Bray, W. L. 1904. The timber of the Edwards Plateau of Texas: Its relations to climate, water supply, and soil. No. 49. US Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Forestry.

Briske, D. D., S. D. Fuhlendorf, and F. E. Smeins. 2005. State-and-transition models, thresholds, and rangeland health: A synthesis of ecological concepts and perspectives. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 58(1):1-10.

Brothers, A., M. E. Ray Jr., and C. McTee. 1998. Producing quality whitetails, revised edition. Texas Wildlife Association, San Antonio, TX.

Brown, J. K. and J. K. Smith. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems, effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 257:42.

Davis, W. B. 1974. The Mammals of Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 41.

Foster, J. H. 1917. The spread of timbered areas in central Texas. Journal of Forestry 15(4):442-445.

Frost, C. C. 1998. Presettlement fire frequency regimes of the United States: A first approximation. Fire in ecosystem management: Shifting the paradigm from suppression to prescription. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 20:70-81.

Gould, F. W. 1975. The grasses of Texas. The Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Hatch, S. L. and J. Pluhar. 1993. Texas Range Plants. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Hamilton, W. and D. Ueckert. 2005. Rangeland woody plant control--past, present, and future. Texas A&M University Press. College Station, TX.

Hart, C. R., A. McGinty, and B. B. Carpenter. 1998. Toxic plants handbook: Integrated management strategies for West Texas. Texas Agricultural Extension Service, The Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

Heitschmidt, R. K. and J. W. Stuth. 1991. Grazing management: An ecological perspective. Timberline Press, Portland, OR.

Loughmiller, C. and L. Loughmiller. 1984. Texas wildflowers. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Milchunas, D. G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 126:169.

Niehaus, T. F. 1998. A field guide to Southwestern and Texas wildflowers (Vol. 31). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, MA.

Ramsey, C. W. 1970. Texotics. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, TX.

Roemer, F. translated by O. Mueller. 1995. Roemer’s Texas, 1845 to 1847. Texas Wildlife Association, San Antonio, TX.

Scifres, C. J. and W. T. Hamilton. 1993. Prescribed burning for brushland management: The South Texas example. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX.

Smeins, F. E., S. Fuhlendorf, and C. Taylor, Jr. 1997. Environmental and land use changes: A long term perspective. Juniper Symposium, 1-21.

Taylor, C. A. and F. E. Smeins. 1994. A history of land use of the Edwards Plateau and its effect on the native vegetation. Juniper Symposium, 94:2.

Thurow, T. L. 1991. Hydrology and erosion. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heitschmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Tull, D. and G. O. Miller. 1991. A field guide to wildflowers, trees and shrubs of Texas. Texas Monthly Publishing, Houston, TX.

USDA-NRCS. 1997. National range and pasture handbook. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture. Natural Resources Conservation Service, Grazing Lands Technology Institute.

Weniger, D. 1997. The explorers’ Texas: The animals they found. Eakin Press, Austin, TX.

Weniger, D. 1984. The explorers’ Texas: The lands and waters. Eakin Press, Austin, TX.

Vines, R. A. 1984. Trees of Central Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Vines, R. A. 1960. Trees, shrubs and vines of the Southwest. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Contributors

Dr. Joseph Schuster, Range & Wildlife Habitat Consultants, LLC, Bryan, TX

Mark Moseley, RMS, NRCS, Boerne, TX

Edits by Travis Waiser, MLRA Leader, NRCS, Kerrville, TX

Acknowledgments

Reviewers and Technical Contributors:

Charles Anderson, RMS, NRCS, San Angelo, TX

Mark Ramirez, DC, NRCS, Sterling City, TX

Rusty Dowell, RSS, NRCS, San Angelo, TX

Julia McCormick, RSS, NRCS, Kerrville, TX

Mark Moseley, RMS, NRCS, San Antonio, TX

Justin, Clary, RMS, NRCS, Temple, TX

QC/QA completed by:

Bryan Christensen, SRESS, NRCS, Temple, TX

Erin Hourihan, ESDQS, NRCS, Temple, TX

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Joe Franklin, Zone RMS, NRCS, San Angelo, TX |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | 325-944-0147 |

| Date | 12/21/2008 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None to slight. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Water flow patterns are common,and follow old drainage patterns. Erosion and deposition is uncommon but may occur during intense rainfall events. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

None to few. Uncommon for this site. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Bare ground is 5 to 15 percent, randomly distributed. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

Some gullies may be present, but they should be vegetated and stable. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Little movement of any size. However, litter of all sizes can be expected to move considerable distances under intense rainfall events. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Bare soil surface moderately resistant to erosion. Little erosion occurs under reference conditions. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

Surface soil is 0 to 7 inches and brown silty clay loam, weak sub-angular blocky structure. Soil organic matter 1 to 5 percent. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

The climax Midgrass Prairie vegetation provides maximum infiltration, percolation, and little runoff. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm-season midgrassesSub-dominant:

Warm-season shortgrasses Cool-season grasses = Forbs =Other:

Shrubs/Vines TreesAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Perennial grasses will naturally exhibit a minor amount (less than five percent) of senescence and some mortality every year. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Litter is primarily herbaceous. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

600 to 2,500 pounds per acre. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Mesquite, pricklypear, lotebush, and tasajillo. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All perennial species should be capable of reproducing every year unless disrupted by extended drought, overgrazing, wildfire, insect damage, or other events occurring immediately prior to, or during the reproductive phase.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, may be coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Extensive soil disturbance followed by seeding |

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of historic disturbance return intervals |

| T2A | - | Extensive soil disturbance followed by seeding |

| T3A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, may be coupled with excessive grazing pressure |