Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R081BY348TX

Steep Adobe 23-31 PZ

Last updated: 9/19/2023

Accessed: 03/14/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

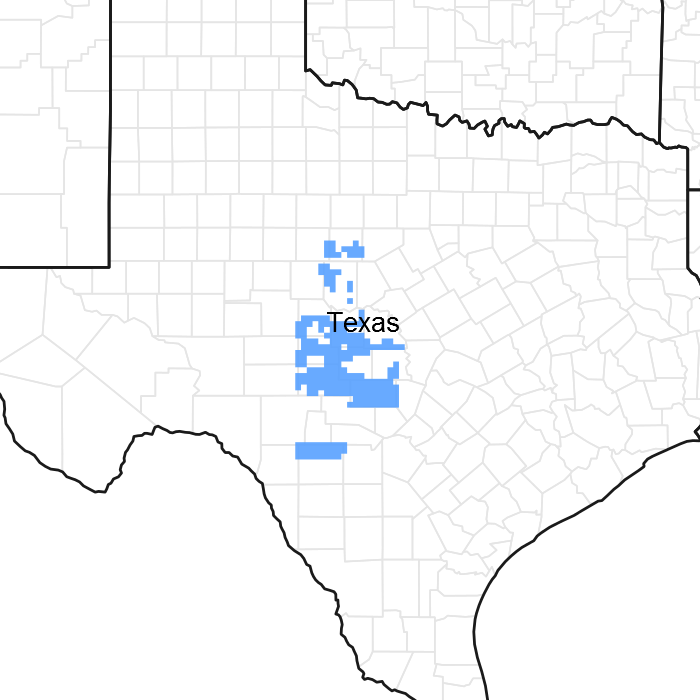

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 081B–Edwards Plateau, Central Part

This area is entirely in south-central Texas. It makes up about 11,125 square miles (28,825 square kilometers). The towns of Fredericksburg, Junction, Menard, Rocksprings, and Sonora are in this MLRA. Interstate 10 crosses the middle part of the area. A few State parks and State historic sites are in this MLRA.

Classification relationships

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006.

-Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 81B

Ecological site concept

Steep Adobe sites are located on uplands with greater than 20 percent slope. They have soils less than 20 inches deep over the Glenrose Formation.

Associated sites

| R081BY320TX |

Adobe 23-31 PZ The Adobe site are on slopes less than 20 percent. |

|---|---|

| R081BY328TX |

Deep Redland 23-31 PZ The Deep Redland site has deeper soils on slopes less than 20 percent with red subsoil and Post oak trees. |

| R081BY340TX |

Redland 23-31 PZ The Redland site has slopes less than 20 percent with red subsoil and Post oak trees. |

Similar sites

| R081BY350TX |

Steep Rocky 23-31 PZ The Steep Rocky site has the same slopes but has more gravels, cobbles, and stones on the surface and in the soil. |

|---|---|

| R081BY320TX |

Adobe 23-31 PZ The Adobe site are the same soils but on slopes less than 20 percent. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Quercus virginiana |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Schizachyrium scoparium |

Physiographic features

The Steep Adobe site is found on steep upland ridges and foothills. Slopes are complex and range from 20 to 50 percent. This site is found primarily along the base of limestone hills that slope toward rivers or larger permanent or ephemeral creeks. Areas are irregular in shape and range from a few to several hundred acres. Runoff is medium to high and the potential erosion is high. The elevation ranges from 1,000 to 2,500 feet.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Plateau

> Ridge

|

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Medium to high |

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 305 – 762 m |

| Slope | 20 – 50% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate in the MLRA 81B is subtropical subhumid on the eastern portion and subtropical steppe on the western portion of the MLRA. Winters are dry, and the summers are hot and humid. The precipitation increases from west to east and the temperatures increase from north to south. The area usually receives 65 to 70 percent sunshine each year. The majority of the rainfall occurs during the warm months of April to October. Most precipitation comes from thunderstorms that vary in the amount of water received and the areas covered. Spring is characterized by fluctuating patterns, but mild temperatures prevail. July and August are relatively dry and hot with little weather variability day-to-day. As summer progresses through fall, an increase of precipitation usually occurs in the eastern portions while a decrease of precipitation occurs to the west. Winter temperatures are mild, but polar Canadian air masses bring rapid drops in temperature. These cold spells last 2 or 3 days. Prevailing winds are southerly with March and April the windiest months.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 210-270 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 240-290 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 635-711 mm |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 210-270 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 240-290 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 610-762 mm |

| Frost-free period (average) | 230 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 265 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 686 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BRADY [USC00411017], Brady, TX

-

(2) EDEN [USC00412741], Eden, TX

-

(3) FREDERICKSBURG [USC00413329], Fredericksburg, TX

-

(4) FT MCKAVETT [USC00413257], Fort Mc Kavett, TX

-

(5) HUNT 10 W [USC00414375], Hunt, TX

-

(6) JUNCTION KIMBLE CO AP [USW00013973], Junction, TX

-

(7) JUNCTION 4SSW [USC00414670], Junction, TX

-

(8) MENARD [USC00415822], Menard, TX

-

(9) ROCKSPRINGS 1S [USC00417706], Rocksprings, TX

-

(10) SAN SABA [USC00417992], San Saba, TX

Influencing water features

This is an upland site and is not influenced by water from a wetland or stream.

Wetland description

N/A

Soil features

The soils are very shallow, shallow, and moderately deep on steep upland ridges and foothills. They are moderately alkaline grayish brown gravelly clay loam to pale brown gravelly loam, 8 to 40 inches deep. Underlying layers vary from weakly cemented platy limestone that becomes chalky and marly with depth to weakly cemented limestone fragments to very pale clay loam that has rock-like structure. These soils have low natural fertility. They are well drained. Permeability is moderate and water capacity is very low. The root zone is shallow. The hazard of water erosion is severe, and the hazard of soil blowing is moderate. The soils are not suitable for cultivation. Soil series correlated to this site include: Brackett, Kerrville, Real, and Stilskin.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

limestone

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Gravelly loam (2) Gravelly clay loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy-skeletal (2) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate |

| Depth to restrictive layer | 20 – 102 cm |

| Soil depth | 20 – 102 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 30% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0 – 30% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

1.52 – 10.92 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

40 – 85% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

7.4 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (10.2-101.6cm) |

5 – 45% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (10.2-101.6cm) |

2 – 20% |

Table 5. Representative soil features (actual values)

| Drainage class | Not specified |

|---|---|

| Permeability class | Slow to moderate |

| Depth to restrictive layer | Not specified |

| Soil depth | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

Not specified |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

Not specified |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

Not specified |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

Not specified |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (10.2-101.6cm) |

Not specified |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (10.2-101.6cm) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

The Steep Adobe site was most likely a mid and tallgrass savannah. Slope and geologic structure has a strong influence on the composition of the plant community. Slopes below about 20 percent, usually with deeper soils and more soil moisture, normally produced more grass cover. The higher production was not only valuable for forage and erosion control but provided fuel for periodic fires. Caused by lightning or set by Native Americans, fire helped keep the woody species suppressed. Slopes ranging from 20 to 50 percent tended to be rockier, droughtier, less productive and more varied in topography, thus experiencing less intensive and spottier fires. This created a more mosaic pattern of herbaceous and woody vegetation. On average, fires occurred every 7 to 12 years.

Besides fire and climate, including extended periods of drought, grazing greatly influenced the plant community. Although preferring more open country, resident herds of pronghorn could forage on the lower, flatter slopes. Populations of white-tailed deer made use of the browse and forbs available. Bison grazing was intermittent. The large resident herds ranged to the north and west, but the area was visited periodically by bison when conditions were favorable. Furbearers, quail, dove, and songbirds fed on seeds and fruit produced, as did Rio Grande turkey. This interaction between herbivores and plants helped maintain the reference community.

Extremes in climate exerted tremendous influence on the site long before European man arrived. Geologic formations, archeological findings and rainfall records since the mid-1900’s show wide variations in precipitation, with cycles of long, dry periods going back thousands of years. Reference community plants developed ways to withstand periods of drought. The grasses and forbs shaded the ground, reduced soil temperature, improved infiltration and maintained soil moisture. Roots of midgrass, tallgrass, and perennial forbs reached deeper into the soil, utilizing deep soil moisture no longer available to short-rooted plants. In extreme periods of drought, many species could go virtually dormant, preserving the energy stored in underground bases and roots until wetter weather arrived. Their seeds could stay viable in the soil for long periods, sprouting when conditions improved.

While periodic grazing is a natural component of this ecosystem, overstocking and thus overgrazing by domesticated animals has had a tremendous impact. Arriving in numbers in the 1840’s and 50’s, most early settlers were accustomed to ranching in more temperate zones of the eastern United States or even Europe and misjudged the capacity of the site for sustainable production, expecting more than the land could deliver. Overgrazing, usually in the form of heavy continuous grazing by cattle, sheep, and goats, and fire suppression disrupted ecological processes that took hundreds or thousands of years to develop. Instead of grazing and moving on, domestic livestock was present on the site most of the time. Steep Adobe is often in close proximity to streams and so was particularly hard-hit by livestock traveling to and from water, bedding down, or just being held close to water during roundups. The arrival of barbed wire fencing in the late 1870’s could have been used as a conservation tool, but for the most part, was just used to contain livestock. Another influence on grazing patterns was the advent of windmills during the same period. The windmills allowed large areas to be grazed that were previously unused by livestock due to lack of natural surface water.

As cattle fed primarily on grasses and the forbs and browse were prime forage for sheep, goats, and deer, the more palatable plants such as little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Indiangrass (Sorgastrum nutans), cane bluestem (Bothriochloa barbinodis), sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), awnless bushsunflower (Simsia calva) and orange zexmenia (Wedelia hispida) were selected repeatedly and eventually began to disappear. These were replaced by lower successional, less palatable and productive species such as slim tridens (Tridens muticus), silver bluestem (Bothriochloa laguroides ssp. torreyana), hairy grama (Bouteloua hirsuta), Wright’s three-awn (Aristida purpurea var. purpurea), Queen’s delight (Stillingia sylvatica ssp. sylvatica), and annual forbs. As overgrazing continued, overall production of grasses and forbs declined, more bare ground appeared, soil erosion increased and woody and succulent increasers such as Texas oak (Quercus buckleyi), Ashe juniper (Juniperus ashei), cenizo (Leucophyllum frutescens), agarito (Mahonia trifiolata), yucca (Yucca spp.), catclaw mimosa (Mimosa biuncifera), catclaw acacia (Acacia gregii), and mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) began to multiply. The elimination of fire due to the lack of fine fuel or by human interference assisted the rapid encroachment by herbaceous and woody increasers/invaders with a concurrent reduction of usable forage and growing danger from toxic plants.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, may be coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of historic disturbance return intervals |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Savannah

Dominant plant species

-

live oak (Quercus virginiana), tree

-

Texas red oak (Quercus buckleyi), tree

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

Community 1.1

Mid and Tallgrass Savannah

The reference plant community (1.1) for this site is a savannah composed of mid and tallgrasses with scattered trees and shrubs that evolved under the influence of grazing, periodic fire, and climate. The overstory shades about 10 to 15 percent of the site and consists of trees such as Texas oak, (Quercus buckleyi), live oak (Quercus virginiana), Lacey oak (Quercus laceyi), Texas redbud (Cercis canadensis var. texensis), Ashe juniper, and shrubs such as evergreen sumac (Rhus virens), littleleaf sumac (Rhus microphylla), Texas kidneywood (Eysenhardtia texana), littleleaf leadtree (Leucaena retusa), and elbowbush (Forestiera pubescens). Approximately 75 percent of the vegetative canopy is grasses, with little bluestem being the single most productive species. Other important grasses include Indiangrass, sideoats grama, green sprangletop (Leptochloa dubia), plains lovegrass (Eragrostis intermedia), cane bluestem (Bothriochloa barbinodis), silver bluestem (Bothriochloa laguroides var. torreyana) and tall dropseed (Sporobolus compositus var. compositus). Shorter and/or less productive grasses found in some quantity include several species of muhly (Muhlenbergia spp.), hairy dropseed (Sporobolus compositus var. drummondii), slim tridens, rough tridens (Tridens muticus var. muticus), Wright’s three-awn and fall witchgrass (Digitaria cognata). Perennial forbs such as awnless bushsunflower, catclaw sensitivebriar (Mimosa nutallii), Engelmann’s daisy (Engelmannia perestinia), knotweed leaflower (Phyllanthus polygonoides) and orange zexmenia are a small (around five percent) but important component of the plant community, particularly for foragers such as deer that need a diet higher in protein than that furnished by grass alone. In wet years, annual forbs may produce significant herbaceous vegetation. Plant vigor and reproduction is relatively high in favorable weather but somewhat limited by the high lime content of the soil. Soil erosion, particularly on the flatter slopes is controlled. With high runoff rates and slow infiltration, the vegetative ground cover helps disperse and slow down runoff, thus holding soil in place and enhancing infiltration. Concentrated water flow patterns are rare. Recurrent fire, climate patterns and grazing by herbivores are natural processes that maintain this very fragile ecological site. Change occurs when ecological processes are interrupted. Continued overuse, elimination of fire, and extended drought can result in the decline or disappearance of the historic populations of quality grasses and forbs. More dominant, palatable grasses and perennial forbs decrease and less palatable or productive midgrasses, shortgrasses, forbs, and woody species begin to increase and fill in the void left by the declining species. More prominent in the landscape are grasses like Wright’s three-awn, slim tridens, rough tridens (Tridens muticus var. muticus), hairy dropseed (Sporobolus compositus var. drummondii), and hairy grama. Queen’s delight and annual forbs are more numerous. The woody canopy is approximately double, with noticeable increases in Texas oak and Ashe juniper production. The decrease in vegetative ground cover facilitates lower infiltration, higher runoff rates and concentration of water flow, thus promoting soil erosion. If the process is not reversed, the community shifts toward the Mid and Shortgrass Savannah Community (1.2).

Figure 8. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 857 | 1480 | 2219 |

| Tree | 106 | 185 | 448 |

| Forb | 56 | 95 | 146 |

| Shrub/Vine | 56 | 95 | 146 |

| Total | 1075 | 1855 | 2959 |

Figure 9. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX3622, Mid and Shortgrass Savannah, 10% canopy. Mid and shortgrasses dominate the site with less than 20 percent forbs, shrubs, and woody plants..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 13 | 23 | 15 | 4 | 5 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 3 |

Community 1.2

Mid and Shortgrass Savannah

This community still resembles a Mid and Tallgrass Savannah Community (1.1) plant structure to casual observation. However, due to the measurable decline of dominant midgrasses, tallgrasses, and perennial forbs caused by overstocking, elimination of fire, lack of brush management and, possibly, long-term changes in weather patterns, the population of Texas oak, Ashe juniper and other trees and shrubs begins to increase. Vigor and reproduction of the dominant grass species decline and are starting to be replaced by slim tridens, rough tridens, fall witchgrass, Wright’s three-awn, hairy grama, red grama (Bouteloua trifida) and other short grasses. Less palatable annual and perennial forbs increase. Shrub canopy has slightly increased overall but has a higher proportion of less palatable species. More Ashe juniper plants are apparent, as are a few occasional scrubby mesquite seedlings. Production of Texas and other oak species is nearly doubled. Ground cover by litter decreases. Soil organic matter is decreasing. Infiltration begins to drop off and runoff increases. Signs of erosion begin to appear. Encroachment by brush, replacement of mid and tallgrasses, loss of topsoil and loss of soil organic matter make it difficult for these abused areas to return to the historic plant community even if stressors are removed. However, the retrogression at this point can be halted or reversed, particularly on lower slopes, with relatively small labor and cost input if measures are taken soon enough. Application of prescribed grazing is essential to stop the decline of high quality plants. Grazing management is more critical in maintaining the vegetative cover on this steep adobe site due to the increase of erosion potential. Prescribed burning can be used where practical to control small woody plants and their seedlings, especially Ashe juniper up to four feet tall. These can also be controlled through individual plant treatment (ITP) mechanically or with appropriate chemical application.

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Change occurs when ecological processes are interrupted. Continued overuse, elimination of fire, and extended drought can result in the decline or disappearance of the historic populations of quality grasses and forbs. More dominant, palatable grasses and perennial forbs decrease and less palatable or productive midgrasses, shortgrasses, forbs, and woody species begin to increase and fill in the void left by the declining species. More prominent in the landscape are grasses like Wright’s three-awn, slim tridens, rough tridens (Tridens muticus var. muticus), hairy dropseed (Sporobolus compositus var. drummondii), and hairy grama. Queen’s delight and annual forbs are more numerous. The woody canopy is approximately double, with noticeable increases in Texas oak and Ashe juniper production. The decrease in vegetative ground cover facilitates lower infiltration, higher runoff rates and concentration of water flow, thus promoting soil erosion. If the process is not reversed, the community shifts toward the Mid and Shortgrass Savannah Community (1.2).

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

This trend in a Steep Adobe reference plant community can likely be reversed and productivity restored, but due to the topography and soil, the window of opportunity is limited, and quick action is imperative if this community is identified. The site is quite fragile, and degradation occurs rapidly once started. Understanding the effects of climate, fire, and grazing on the ecology of the site combined with the use of sound grazing management, judicious brush management and prescribed burning where practical is key to any attempt to return to the reference community.

State 2

Wooded

Dominant plant species

-

Texas live oak (Quercus fusiformis), tree

-

Ashe's juniper (Juniperus ashei), tree

Community 2.1

Oak/Juniper/Shrub Complex

This plant community is the result of an extreme shift of site characteristics from the original Mid and Tallgrass Savannah Community (1.1). Texas oak, Lacey oak, Ashe juniper, Hercules-club pricklyash (Zanthoxylum clava-herculis), cenizo, algerita, catclaw mimosa (Mimosa biuncifera), catclaw acacia (Acacia gregii), mesquite, yucca, and other woody increasers/invaders dominate the slopes. Cenizo is very apparent on the lower slopes and will readily take over areas cleared of brush with no follow-up grazing management. This strong competition for water, sunlight, and nutrients has severely limited lower successional short and midgrasses, let alone those of the reference community. Various threeawn (Aristida spp.) species, hairy grama, red grama, hairy tridens (Erioneuron pilosum), Texas wintergrass (Nassella leucotricha), cedar sedge (Carex planostachys), and annuals dominate the grass-like plant population. The forb population is predominantly annuals and unpalatable perennials. Some, such as Queen’s delight, have toxic properties. Up to 80 percent of the ground can be bare of herbaceous vegetation. Bare soil has crusted and is relatively impermeable to moisture. Very little rainfall infiltrates and runoff is rapid. Most of the original, fertile topsoil has eroded away and various-sized gullies have formed, some can be very large.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

The Mid and Shortgrass Savannah community (1.2) is the most short-lived community on this very fragile Steep Adobe site unless the transition is halted or reversed. If left in place, the factors that caused the transition from the reference community will accelerate and in a relatively short time cause the transition from this community to the Oak/Juniper/Shrub Complex community (2.1).

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

The potential for restoring this community to the reference state within a reasonable amount of time is extremely low. With the possible exception of some lower slopes, decades of transition have robbed the site of the soil properties, species diversity, site integrity, and hydrological features essential for restoration. The difficulties of attempting brush management are usually prohibitive for most land uses due to the terrain and the high extensive cost requirements. Prescribed grazing or even reducing the amount of grazing by livestock can also assist in the development of desirable habitat for wildlife and the recreational activities that accompany it.

Additional community tables

Table 7. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Tallgrass | 465–869 | ||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | 465–869 | – | ||

| 2 | Tallgrass | 95–280 | ||||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 95–280 | – | ||

| 3 | Midgrasses | 185–448 | ||||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 185–448 | – | ||

| silver beardgrass | BOLAT | Bothriochloa laguroides ssp. torreyana | 185–448 | – | ||

| plains lovegrass | ERIN | Eragrostis intermedia | 185–448 | – | ||

| green sprangletop | LEDU | Leptochloa dubia | 185–448 | – | ||

| composite dropseed | SPCOC2 | Sporobolus compositus var. compositus | 185–448 | – | ||

| dropseed | SPORO | Sporobolus | 185–448 | – | ||

| 4 | Midgrasses | 39–151 | ||||

| tall grama | BOHIP | Bouteloua hirsuta var. pectinata | 39–146 | – | ||

| Drummond's dropseed | SPCOD3 | Sporobolus compositus var. drummondii | 39–146 | – | ||

| 5 | Midgrasses | 39–146 | ||||

| hairy grama | BOHIH | Bouteloua hirsuta var. hirsuta | 39–146 | – | ||

| muhly | MUIN | Muhlenbergia ×involuta | 39–146 | – | ||

| Lindheimer's muhly | MULI | Muhlenbergia lindheimeri | 39–146 | – | ||

| seep muhly | MURE2 | Muhlenbergia reverchonii | 39–146 | – | ||

| 6 | Midgrasses | 39–146 | ||||

| threeawn | ARIST | Aristida | 39–146 | – | ||

| Wright's threeawn | ARPUW | Aristida purpurea var. wrightii | 39–146 | – | ||

| fall witchgrass | DICO6 | Digitaria cognata | 39–146 | – | ||

| slim tridens | TRMU | Tridens muticus | 39–146 | – | ||

| slim tridens | TRMUE | Tridens muticus var. elongatus | 39–146 | – | ||

| 7 | Cool Season Grasses | 39–146 | ||||

| cedar sedge | CAPL3 | Carex planostachys | 39–146 | – | ||

| Texas wintergrass | NALE3 | Nassella leucotricha | 39–146 | – | ||

| 8 | Shortgrasses | 6–39 | ||||

| Grass, annual | 2GA | Grass, annual | 6–39 | – | ||

| red grama | BOTR2 | Bouteloua trifida | 6–39 | – | ||

| hairy woollygrass | ERPI5 | Erioneuron pilosum | 6–39 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 9 | Forbs | 56–146 | ||||

| velvet bundleflower | DEVE2 | Desmanthus velutinus | 56–146 | – | ||

| Engelmann's daisy | ENPE4 | Engelmannia peristenia | 56–146 | – | ||

| milkpea | GALAC | Galactia | 56–146 | – | ||

| Maximilian sunflower | HEMA2 | Helianthus maximiliani | 56–146 | – | ||

| Chalk Hill hymenopappus | HYTE2 | Hymenopappus tenuifolius | 56–146 | – | ||

| trailing krameria | KRLA | Krameria lanceolata | 56–146 | – | ||

| dotted blazing star | LIPU | Liatris punctata | 56–146 | – | ||

| hoary blackfoot | MECIH | Melampodium cinereum var. hirtellum | 56–146 | – | ||

| showy menodora | MELO2 | Menodora longiflora | 56–146 | – | ||

| Nuttall's sensitive-briar | MINU6 | Mimosa nuttallii | 56–146 | – | ||

| smartweed leaf-flower | PHPO3 | Phyllanthus polygonoides | 56–146 | – | ||

| awnless bushsunflower | SICA7 | Simsia calva | 56–146 | – | ||

| queen's-delight | STSY | Stillingia sylvatica | 56–146 | – | ||

| creepingoxeye | WEDEL | Wedelia | 56–146 | – | ||

| 10 | Annual Forbs | 6–34 | ||||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 6–34 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 11 | Shrubs/Vines | 56–146 | ||||

| Texas kidneywood | EYTE | Eysenhardtia texana | 56–146 | – | ||

| stretchberry | FOPU2 | Forestiera pubescens | 56–146 | – | ||

| Texas barometer bush | LEFR3 | Leucophyllum frutescens | 56–146 | – | ||

| winged sumac | RHCO | Rhus copallinum | 56–146 | – | ||

| littleleaf sumac | RHMI3 | Rhus microphylla | 56–146 | – | ||

| evergreen sumac | RHVI3 | Rhus virens | 56–146 | – | ||

| bully | SIDER2 | Sideroxylon | 56–146 | – | ||

|

Tree

|

||||||

| 12 | Trees | 95–426 | ||||

| Texas madrone | ARXA80 | Arbutus xalapensis | 95–426 | – | ||

| Texas redbud | CECAT | Cercis canadensis var. texensis | 95–426 | – | ||

| littleleaf leadtree | LERE5 | Leucaena retusa | 95–426 | – | ||

| Texas red oak | QUBU2 | Quercus buckleyi | 95–426 | – | ||

| Lacey oak | QULA | Quercus laceyi | 95–426 | – | ||

| live oak | QUVI | Quercus virginiana | 95–426 | – | ||

| blackhaw | VIPR | Viburnum prunifolium | 95–426 | – | ||

| 13 | Tree | 11–22 | ||||

| Ashe's juniper | JUAS | Juniperus ashei | 11–22 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

This site is used to produce domestic livestock and to provide habitat for native wildlife. Cow-calf operations are the primary livestock enterprise, although stocker cattle are also grazed. Sheep, Angora goats, and Spanish goats were formerly raised in large numbers. Sheep are still present in reduced numbers, while meat goats are now present in fairly high numbers. Boer goats have been introduced, either purebred or crossed with Spanish goats, to obtain a larger meat animal. Reports indicate that Boers do not browse as heavily as earlier breeds.

Sustainable stocking rates have declined drastically over the past 100 years due to deterioration of the reference plant community. An assessment of vegetation is needed to determine the site’s current carrying capacity. Calculations used to determine livestock stocking rate should be based on forage production remaining after determining use by resident wildlife, then refined by frequent careful observation of the plant community’s response to animal foraging.

A large diversity of wildlife is native to this site. In the reference plant community, migrating bison, grazing primarily during wetter periods, pronghorn, white-tailed deer and turkey were the more predominant herbivore species. With the subsequent transformation of the plant community, due primarily to the influence of man and climate change, the kind and proportion of wildlife species have been altered.

Except for a few domestic herds, bison have been eliminated. With the eradication of the screwworm fly, increase in woody vegetation and man-suppressed natural predation, deer numbers have increased and are often in excess of carrying capacity. Where deer numbers are excessive, overbrowsing and overuse of preferred forbs causes deterioration of the plant community. Progressive management of deer populations through hunting can keep populations in balance and provide an economically important ranching enterprise. Achieving a balance between brushy cover and more open plant communities on this and adjacent sites is important to deer management. Competition among deer, sheep, and goats must be a consideration in livestock and wildlife management to prevent damage to the plant community.

Various species of exotic wildlife have been introduced on the site, including deer such as axis, sika, fallow, and red; antelope such as sable, oryx, blackbuck, and nilgai, and sheep such as barbados (mouflon) and aoudad with various degrees of success. Their numbers must be included along with livestock and native wildlife, primarily white-tailed deer, in any management plan. Feral hogs may feed on the site. They can be damaging to the plant community if their numbers are not managed. Smaller mammals include many kinds of rodents, jackrabbit, cottontail, raccoon, ringtail, skunk, and armadillo. Mammalian predators include coyote, red fox, gray fox, bobcat, and mountain lion. Wolves were common in earlier times, bears resided in some areas, and an occasional jaguar or ocelot was encountered. Many species of snakes and lizards are native to the site.

Many species of birds are found on this site including game birds, songbirds, and birds of prey. Major game birds that are economically important are turkey, bobwhite quail, scaled (blue) quail and mourning dove. Turkeys prefer plant communities with substantial amounts of shrubs and trees interspersed with grassland. Quail prefer a combination of low shrubs, bunch grass (critical for nesting cover), bare ground, and low successional forbs. The different species of songbirds vary in their habitat preferences. Habitat on this site that provides a large diversity of grasses, forbs, and shrubs will support a good variety and abundance of songbirds. Birds of prey are important to keep the numbers of rodents, rabbits, and snakes in balance. Different species of raptors benefit from a diverse plant community as well.

Hydrological functions

The soils on this site are well drained with slow/very slow permeability and low/very low water holding capacity. Combined with the slopes of the site, they experience very rapid surface runoff. Water erosion potential is severe.

The existing plant community and its management are essential to the hydrological function of this site. The water cycle functions most effectively when mid and tall bunchgrasses dominate. This condition promotes good soil structure, high organic matter, good porosity and rapid infiltration of water into the soil. Water that does run off will be high quality and erosion and sedimentation will be low.

Loss or reduction of mid and tallgrasses, most frequently through heavy grazing, impairs the water cycle. Ground cover is poor, organic matter is low, soil structure breaks down and the surface becomes capped. Infiltration decreases and runoff increases. Erosion and sedimentation are accelerated. Given the excessive slopes of the site, in this condition it can contribute to increased frequency and flooding within a watershed yet remain droughty between heavy rainfall events.

Recreational uses

With its rugged landscape and diverse foliage the site can be quite scenic, particularly in the fall. Many plants native to the site, such as Texas oak, have been incorporated into home or park landscapes. The site supports a wide variety of wildlife. The area is heavily used for hunting various native and introduced game animals and birds. Other popular uses are hiking, birding, photography, and related eco-tourism enterprises.

Wood products

Oaks and Ashe juniper may be used for fencing, firewood, or in the specialty wood industry. Oils can be extracted from Ashe juniper for commercial uses.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented here is derived from literature, limited NRCS clipping data (417s), field observations, and personal contacts with range-trained personnel.

Other references

Archer, S. 1994. Woody plant encroachment into southwestern grasslands and savannas: Rates, patterns, and proximate causes. Ecological implications of livestock herbivory in the West, 13-68.

Archer, S. and F. E. Smeins. 1991. Ecosystem-level processes. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heischmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Bestelmeyer, B. T., J. R. Brown, K. M. Havstad, R. Alexander, G. Chavez, and J. E. Herrick. 2003. Development and use of state-and-transition models for rangelands. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):114-126.

Bracht, V. 1931. Texas in 1848. German-Texan Heritage Society, Department of Modern Languages, Southwest Texas State University, San Marcos, TX.

Bray, W. L. 1904. The timber of the Edwards Plateau of Texas: Its relations to climate, water supply, and soil. No. 49. US Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Forestry.

Briske, D. D., S. D. Fuhlendorf, and F. E. Smeins. 2005. State-and-transition models, thresholds, and rangeland health: A synthesis of ecological concepts and perspectives. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 58(1):1-10.

Brothers, A., M. E. Ray Jr., and C. McTee. 1998. Producing quality whitetails, revised edition. Texas Wildlife Association, San Antonio, TX.

Brown, J. K. and J. K. Smith. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems, effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 257:42.

Davis, W. B. 1974. The Mammals of Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 41.

Foster, J. H. 1917. The spread of timbered areas in central Texas. Journal of Forestry 15(4):442-445.

Frost, C. C. 1998. Presettlement fire frequency regimes of the United States: A first approximation. Fire in ecosystem management: Shifting the paradigm from suppression to prescription. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 20:70-81.

Gould, F. W. 1975. The grasses of Texas. The Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Hatch, S. L. and J. Pluhar. 1993. Texas Range Plants. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Hamilton, W. and D. Ueckert. 2005. Rangeland woody plant control--past, present, and future. Texas A&M University Press. College Station, TX.

Hart, C. R., A. McGinty, and B. B. Carpenter. 1998. Toxic plants handbook: Integrated management strategies for West Texas. Texas Agricultural Extension Service, The Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

Heitschmidt, R. K. and J. W. Stuth. 1991. Grazing management: An ecological perspective. Timberline Press, Portland, OR.

Loughmiller, C. and L. Loughmiller. 1984. Texas wildflowers. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Milchunas, D. G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 126:169.

Niehaus, T. F. 1998. A field guide to Southwestern and Texas wildflowers (Vol. 31). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, MA.

Ramsey, C. W. 1970. Texotics. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, TX.

Roemer, F. translated by O. Mueller. 1995. Roemer’s Texas, 1845 to 1847. Texas Wildlife Association, San Antonio, TX.

Scifres, C. J. and W. T. Hamilton. 1993. Prescribed burning for brushland management: The South Texas example. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX.

Smeins, F. E., S. Fuhlendorf, and C. Taylor, Jr. 1997. Environmental and land use changes: A long term perspective. Juniper Symposium, 1-21.

Taylor, C. A. and F. E. Smeins. 1994. A history of land use of the Edwards Plateau and its effect on the native vegetation. Juniper Symposium, 94:2.

Thurow, T. L. 1991. Hydrology and erosion. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heitschmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Tull, D. and G. O. Miller. 1991. A field guide to wildflowers, trees and shrubs of Texas. Texas Monthly Publishing, Houston, TX.

USDA-NRCS. 1997. National range and pasture handbook. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture. Natural Resources Conservation Service, Grazing Lands Technology Institute.

Weniger, D. 1997. The explorers’ Texas: The animals they found. Eakin Press, Austin, TX.

Weniger, D. 1984. The explorers’ Texas: The lands and waters. Eakin Press, Austin, TX.

Vines, R. A. 1984. Trees of Central Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Vines, R. A. 1960. Trees, shrubs and vines of the Southwest. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Contributors

Bruce Deere

Edits by Travis Waiser, MLRA Leader, NRCS, Kerrville, TX

Acknowledgments

QC/QA completed by:

Bryan Christensen, SRESS, NRCS, Temple, TX

Erin Hourihan, ESDQS, NRCS, Temple, TX

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Joe Franklin, Zone RMS, NRCS, San Angelo, Texas |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | 325-944-0147 |

| Date | 12/02/2005 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Water flow patterns are common and follow old stream meanders. Deposition or erosion is uncommon for normal rainfall but may occur during intense rainfall events. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

Pedestals or terracettes would have been uncommon for this site when occupied by the natural reference plant community. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Expect no more than 40 percent bare ground randomly distributed throughout. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

Some gullies may be present on side drains into perennial and intermittent streams. Gullies should be vegetated and stable. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Under normal rainfall, little litter movement should be minimal and short; however, litter of all sizes may move long distances. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil surface under reference conditions is not resistant to erosion. Available water capacity is low. Severe water erosion hazard is expected. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

Soils are 0 to 6 inches of light, yellowish-brown clay with a moderate fine subangular blocky structure. Limestone bedrock occurs at 10 to 20 inches. SOM is approximately 1 to 6 percent. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

The savannah of tallgrasses, midgrasses, and forbs having adequate litter and little bare ground can provide for maximum infiltration and little runoff under normal rainfall events. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

No evidence of compaction. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Warm-season tallgrasses Warm-season midgrasses Warm-season shortgrasses Cool-season grasses Forbs Shrubs TreesOther:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Minimal and mortality or decadence is expected. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

1,000 pounds per acre for years with below average rainfall and 3,500 pounds per acre for years with above average rainfall. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Ashe juniper, honey mesquite, pricklypear, bermudagrass, johnsongrass, and King Ranch bluestem. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All perennial plants should be capable of reproducing, except during periods of prolonged drought conditions, heavy natural herbivory, and/or extense wildfires.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, may be coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of historic disturbance return intervals |