Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R083AY010TX

Vega

Last updated: 9/19/2023

Accessed: 02/27/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 083A–Northern Rio Grande Plain

This area is entirely in Texas and south of San Antonio. It makes up about 11,115 square miles (28,805 square kilometers). The towns of Uvalde, Cotulla, and Hondo are in the western part of the area, and Beeville, Goliad, and Kenedy are in the eastern part. The town of Alice is just outside the southern edge of the area. Interstate Highways 35 and 37 cross this area. This area is comprised of inland, dissected coastal plains.

Classification relationships

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006.

-Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 83A

Ecological site concept

Sites have deep sands, high levels of calcium carbonates, and are prone to flooding.

Associated sites

| R083AY022TX |

Loamy Sand |

|---|---|

| R083AY023TX |

Sandy Loam |

| R083AY024TX |

Tight Sandy Loam |

Similar sites

| R083BY010TX |

Vega |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Trichloris |

Physiographic features

These are nearly flat soils found in river valleys. Slopes range from 0 to 1 percent and occasionally flood. Due to the sandy nature of the soil, flooding is not lengthy. This area is comprised of inland, dissected coastal plains.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

River valley

> Flood plain

(2) Coastal plain > Flood plain |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible |

| Flooding duration | Extremely brief (0.1 to 4 hours) to very brief (4 to 48 hours) |

| Flooding frequency | Occasional |

| Elevation | 200 – 1,000 ft |

| Slope | 1% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

MLRA 83A is subtropical, subhumid on the western boundary and subtropical humid on the eastern boundary. Winters are dry and mild and the summers are hot and humid. Tropical maritime air masses predominate throughout spring, summer, and fall. Modified polar air masses exert considerable influence during winter, creating a continental climate characterized by large variations in temperature. Average precipitation for MLRA 83A is 20 inches on the western boundary and 35 inches on the eastern boundary. Peak rainfall, because of rain showers, occurs late in spring and a secondary peak occurs early in fall. Heavy thunderstorm activities increase in April, May, and June. July is hot and dry with little weather variations. Rainfall increases again in late August and September as tropical disturbances increase and become more frequent. Tropical air masses from the Gulf of Mexico dominate during the spring, summer, and fall. Prevailing winds are southerly to southeasterly throughout the year except in December when winds are predominately northerly.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 223-251 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 263-365 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 25-32 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 208-263 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 254-365 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 24-37 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 235 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 314 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 29 in |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 3. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BEEVILLE 5 NE [USC00410639], Beeville, TX

-

(2) GOLIAD [USC00413618], Goliad, TX

-

(3) CARRIZO SPRINGS 3W [USC00411486], Carrizo Springs, TX

-

(4) CUERO [USC00412173], Cuero, TX

-

(5) FOWLERTON [USC00413299], Fowlerton, TX

-

(6) HONDO [USC00414254], Hondo, TX

-

(7) KARNES CITY 2N [USC00414696], Karnes City, TX

-

(8) MATHIS 4 SSW [USC00415661], Mathis, TX

-

(9) NIXON [USC00416368], Stockdale, TX

-

(10) POTEET [USC00417215], Poteet, TX

-

(11) UVALDE 3 SW [USC00419268], Uvalde, TX

-

(12) CHARLOTTE 5 NNW [USC00411663], Charlotte, TX

-

(13) CROSS [USC00412125], Tilden, TX

-

(14) PEARSALL [USC00416879], Pearsall, TX

-

(15) TILDEN 4 SSE [USC00419031], Tilden, TX

-

(16) CHEAPSIDE [USC00411671], Gonzales, TX

-

(17) DILLEY [USC00412458], Dilley, TX

-

(18) FLORESVILLE [USC00413201], Floresville, TX

-

(19) LYTLE 3W [USC00415454], Natalia, TX

-

(20) PLEASANTON [USC00417111], Pleasanton, TX

-

(21) HONDO MUNI AP [USW00012962], Hondo, TX

-

(22) CALLIHAM [USC00411337], Calliham, TX

Influencing water features

Sites occasionally flood but water permeates quickly due to their sandiness.

Wetland description

N/A

Soil features

The soils are very deep, somewhat excessively drained, rapidly permeable soils that formed in sandy alluvium derived from mixed sources. Zalla is the only series correlated to this site and is classified as a sandy, mixed, hyperthermic Aridic Ustifluvents. There is only one soil component correlated to this ecological site.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

–

sedimentary rock

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Fine sand |

| Family particle size |

(1) Sandy |

| Drainage class | Somewhat excessively drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately rapid |

| Soil depth | 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

3 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

25% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

6.6 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

2% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

The Northern Rio Grande Plain MLRA was a disturbance-maintained system. Prior to European settlement (pre-1825), fire and grazing were the two primary forms of disturbance. Grazing by large herbivores included antelope, deer, and small herds of bison. The infrequent but intense, short-duration grazing by these species suppressed woody species and invigorated herbaceous species. The herbaceous savannah species adapted to fire and grazing disturbances by maintaining belowground tissues. Wright and Bailey (1982) report that there are no reliable records of fire frequency for the Rio Grande Plains because there are no trees to carry fire scars from which to estimate fire frequency. Because savannah grassland is typically of level or rolling topography, a natural fire frequency of three to seven years seems reasonable for this site.

Precipitation patterns are highly variable. Long-term droughts, occurring three to four times per century, cause shifts in species composition by causing die-off of seedlings, less drought-tolerant species, and some woody species. Droughts also reduce biomass production and create open space, which is colonized by opportunistic species when precipitation increases. Wet periods allow midgrasses to increase in dominance.

Historical accounts prior to 1800 identify grazing by herds of wild horses, followed by heavy grazing by sheep and cattle as settlement progressed. Grazing on early ranches changed natural graze-rest cycles to continuous grazing and stocking rates exceeded the carrying capacity. These shifts in grazing intensity and the removal of rest from the system reduced plant vigor for the most palatable species, which on this site were mid-grasses and palatable forbs. Shortgrasses and less palatable forbs began to dominate the site. This shift resulted in lower fuel loads, which reduced fire frequency and intensity. The reduction in fires resulted in an increase in size and density of woody species.

Today, primarily beef cattle graze rangeland and pastureland. However, horse numbers are increasing rapidly on small acreage properties in the region. There are some areas where dairy cattle, poultry, goats, and sheep are locally important. Whitetail deer, wild turkey, bobwhite quail, and dove are the major wildlife species, and hunting leases are a major source of income for many landowners in this area. Introduced pasture has been established on many acres of old cropland and in areas with deeper soils. Buffelgrass is the most common introduced plant on the site and to a lesser extent bermudagrass, guineagrass (Urochloa maxima), and kleingrass, which are more commonly used for hay. Cropland is found in the valleys, bottomlands, and deeper upland soils. Wheat (Triticum spp.), oats Avena spp.), forage and grain sorghum (Sorghum spp.), cotton (Gossypium spp.), and corn (Zea mays) are major crops in the region.

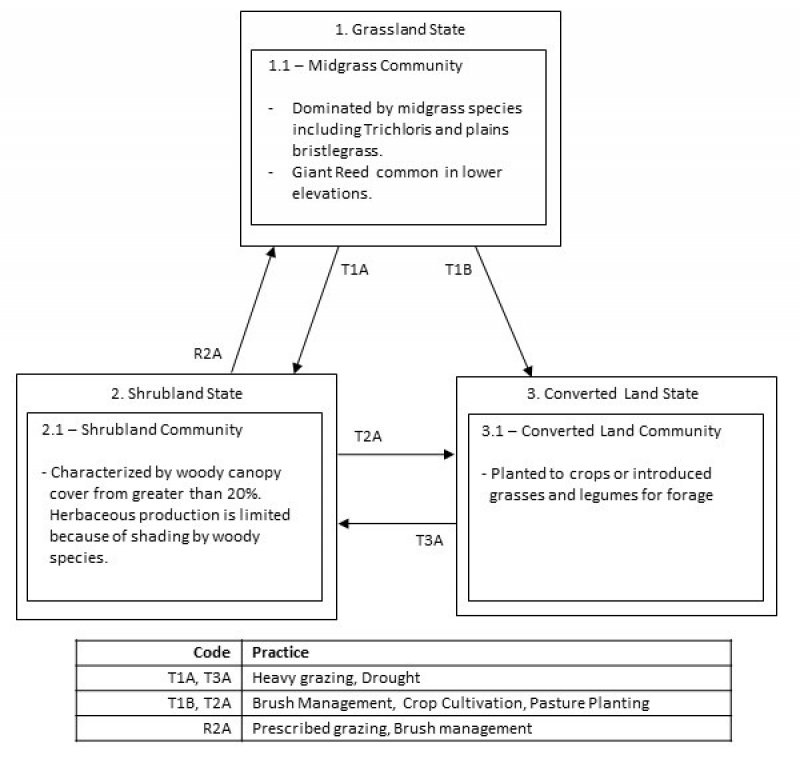

State and transition model

Figure 7. STM

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Prolonged drought coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Removal of native vegetation followed by soil disturbance and seeding of non-native species |

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of natural disturbance return intervals |

| T2A | - | Removal of woody vegetation followed by extensive soil disturbance and seeding of non-native species |

| T3A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Grassland

Dominant plant species

-

false Rhodes grass (Trichloris), grass

-

plains bristlegrass (Setaria vulpiseta), grass

Community 1.1

Midgrass

Vegetation consists of sparse bunches of trichloris (Trichloris spp.), plains bristelgrass (Setaria vulpiseta), hodded windmillgrass (Chloris cucullata), and grassbur (Cenchrus spp.). Higher elevations will contain scattered mesquite (Prosopis spp.) and lower elevations will have dense stands of giant reed (Arundo donax). Bare ground is common between plants due to the sandiness.

Community 2.1

Shrubland

Heavy grazing and drought will cause woody species to increase. Mesquite and a variety of mixed brush will occupy the area. Woody cover greater than 20 percent begins to affect the already diminishing herbaceous production. Bare ground also increases.

State 3

Converted Land

Dominant plant species

-

buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare), grass

-

Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), grass

Community 3.1

Converted Land

Typically, rootplowing and raking is utilized to remove the woody vegetation. A seedbed is then prepared, and the area is planted into grass or crops. This site has historically been planted to buffelgrass, bermudagrass, or introduced bluestems. Now, because of the availability of seed, landowners can also replant with native species. To maintain this seeded state, herbicides must be used to control woody seedlings that invade as soon as the pasture is established. Not only is there a long-lived seed source of woody species, additional seeds are brought in by grazing animals and domestic livestock.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Heavy continuous grazing and drought will transition this site into a Shrubland State (2). The site is characterized by greater than 20 percent woody canopy cover.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Land managers may wish to use this site as pasture, or less commonly cropland. If woody species are present, brush management is necessary to remove trees and shrubs. Seedbed preparation and pasture planting are the final steps needed.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Prescribed grazing and brush management are required to restore the community back to a Grassland State (1). Removal of woody species below 20 percent allows more light and nutrients to herbaceous species. Reducing grazing pressure will allow plants to regain vigor and re-establish.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Land managers may wish to use this site as pasture, or less commonly cropland. Brush management, followed by seedbed preparation and pasture planting are needed to create a successful pasture.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

Without brush management, woody species will encroach and grow into the overstory. The site will transition to a Shrubland State (2) once the woody canopy cover is greater than 20 percent.

Additional community tables

Interpretations

Animal community

As a historic tall/midgrass prairie, this site was occupied by bison, antelope, deer, quail, turkey, and dove. This site was also used by many species of grassland songbirds, migratory waterfowl, and coyotes. This site now provides forage for livestock and is still used by quail, dove, migratory waterfowl, grassland birds, coyotes, and deer.

Feral hogs (Sus scrofa) can be found on most ecological sites in Texas. Damage caused by feral hogs each year includes, crop damage by rutting up crops, destroyed fences, livestock watering areas, and predation on native wildlife. Feral hogs have few natural predators, thus allowing their population to grow to high numbers.

Wildlife habitat is a complex of many different plant communities and ecological sites across the landscape. Most animals use the landscape differently to find food, shelter, protection, and mates. Working on a conservation plan for the whole property, with a local professional, will help managers make the decisions that allow them to realize their goals for wildlife and livestock.

Grassland State (1): This state provides the maximum amount of forage for livestock such as cattle. It is also utilized by deer, quail and other birds as a source of food. When a site is in the reference plant community phase (1.1) it will also be used by some birds for nesting if other habitat requirements like thermal and escape cover are near.

Tree/Shrubland Complex (2): This state can be maintained to meet the habitat requirements of cattle and wildlife. Land managers can find a balance that meets their goals and allows them flexibility to manage for livestock and wildlife. Forbs for deer and birds like quail will be more plentiful in this state. There will also be more trees and shrubs to provide thermal and escape cover for birds as well as cover for deer.

Converted Land State (3): The quality of wildlife habitat this site will produce is extremely variable and is influenced greatly by the timing of rain events. This state is often manipulated to meet landowner goals. If livestock production is the main goal, it can be converted to pastureland. It can also be planted to a mix of grasses and forbs that will benefit both livestock and wildlife. A mix of forbs in the pasture could attract pollinators, birds and other types of wildlife. Food plots can also be planted to provide extra nutrition for deer.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented was derived from the revised Range Site, literature, limited NRCS clipping data (417s), field observations, and personal contacts with range-trained personnel.

Other references

AgriLife. 2009. Managing Feral Hogs Not a One-shot Endeavor. AgNews, April 23, 2009. http://agnews.tamu.edu/showstory.php?id=903.

Archer, S. 1995. Herbivore mediation of grass-woody plant interactions. Tropical Grasslands, 29:218-235.

Archer, S. 1995. Tree-grass dynamics in a Prosopis-thornscrub savanna parkland: reconstructing the past and predicting the future. Ecoscience, 2:83-99.

Archer, S. 1994. Woody plant encroachment into southwestern grasslands and savannas: rates, patterns and proximate causes. Ecological implications of livestock herbivory in the West, 13-68.

Archer, S. and F. E. Smeins. 1991. Ecosystem-level Processes. In Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heischmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Baen, J. S. 1997. The growing importance and value implications of recreational hunting leases to agricultural land investors. Journal of Real Estate Research, 14:399-414.

Bailey, V. 1905. North American Fauna No. 25: Biological Survey of Texas. United States Department of Agriculture Biological Survey. Government Printing Office, Washington D. C.

Bestelmeyer, B. T., J.R. Brown, K. M. Havstad, R. Alexander, G. Chavez, and J. E. Herrick. 2003. Development and use of state-and-transition models for rangelands. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):114-126.

Box, T. W. 1960. Herbage production on four range plant communities in South Texas. Journal of Range Management, 13:72-76.

Briske, B B, B. T. Bestelmeyer, T. K. Stringham, and P. L. Shaver. 2008. Recommendations for development of resilience-based State-and-Transition Models. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 61:359-367.

Brown, J. R. and S. Archer. 1999. Shrub invasion of grassland: recruitment is continuous and not regulated by herbaceous biomass or density. Ecology, 80(7):2385-2396.

Diamond, D. D. and T. E. Fulbright. 1990. Contemporary plant communities of upland grasslands of the Coastal Sand Plain, Texas. Southwestern Naturalist, 35:385-392.

Dillehay T. 1974. Late quaternary bison population changes on the Southern Plains. Plains Anthropologist, 19:180-96.

Edward, D. B. 1836. The history of Texas; or, the immigrants, farmers, and politicians guide to the character, climate, soil and production of that country. Geographically arranged from personal observation and experience. J. A. James and Co., Cincinnati, OH.

Everitt, J. H., D. L. Drawe, and R. I. Leonard. 2002. Trees, Shrubs, and Cacti of South Texas. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, TX.

Everitt, J. H., D. L. Drawe, and R. I. Lonard. 1999. Field Guide to the Broad-Leaved Herbaceous Plants of South Texas. Texas Tech University Press. Lubbock, TX.

Foster, J. H. 1917. Pre-settlement fire frequency regions of the United States: a first approximation. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings No. 20.

Foster, W. C., ed. 1998. The La Salle Expedition to Texas: The Journal of Henry Joutel, 1684-1687. Texas State Historical Association, Austin, TX.

Frost, C. C. 1995. Presettlement fire regimes in southeastern marshes, peatlands, and swamps. In: Prodeedings, 19th Tall Timbers fire ecology conference, 39-60. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL.

Fulbright, T. E. and S. L. Beasom. 1987. Long-term effects of mechanical treatment on white-tailed deer browse. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 15:560-564.

Fulbright, T. E., J. A. Ortega-Santos, A. Lozano-Cavazos, and L. E. Ramirez-Yanez. 2006. Establishing vegetation on migrating inland sand dunes in Texas. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 59:549-556.

Fulbright, T. E., D. D. Diamond, J. Rappole, and J. Norwine. The Coastal Sand Plain of Southern Texas. Rangelands, 12:337-340.

Gould, F. W. 1975. The Grasses of Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Grace, J. B., L. K. Allain, H. Q. Baldwin, A. G. Billock, W. R. Eddleman, A. M. Given, C. W. Jeske, and R. Moss. 2005. Effects of prescribed fire in the coastal prairies of Texas. USGS Open File Report 2005-1287.

Hamilton, W. and D. Ueckert. 2005. Rangeland Woody Plant Control: Past, Present, and Future. In: Brush Management: Past, Present, and Future, 3-16. Texas A&M University Press. College Station, TX.

Hansmire, J. A., D. L. Drawe, B. B. Wester and C.M. Britton. 1988. Effect of winter burns on forbs and grasses of the Texas Coastal Prairie. The Southwestern Naturalist, 33(3):333-338.

Heitschmidt R. K., Stuth J. W., eds. 1991. Grazing management: an ecological perspective. Timberline Press, Portland, OR.

Inglis, J. M. 1964. A history of vegetation of the Rio Grande Plains. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Bulletin No. 45, Austin, TX.

Kneuper, C. L., C. B. Scott, and W. E. Pinchak. 2003. Consumption and dispersion of mesquite seeds by ruminants. Journal of Range Management, 56:255-259.

Kramp, B., R. Ansley, and D. Jones. 1998. Effect of prescribed fire on mesquite seedlings. Texas Tech University Research Highlights - Range, Wildlife and Fisheries Management, 29:13.

Le Houerou, H. N. and J. Norwine. 1988. The ecoclimatology of South Texas. In Arid lands: today and tomorrow. Edited by E. E. Whitehead, C. F. Hutchinson, B. N. Timmesman, and R. G. Varady, 417-444. Westview Press, Boulder, CO.

Lehman, V. W. 1965. Fire in the range of Attwater’s prairie chicken. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference, 4:127-143.

Lehman, V. W. 1969. Forgotten Legions: Sheep in the Rio Grande Plain of Texas. Texas Western Press, El Paso, TX.

Mann, C. 2004. 1491. New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. Vintage Books, New York City, NY.

Mapston, M. E. 2009. Feral Hogs in Texas. Rep. Texas Cooperative Extension. 23 Apr. 2009 http://icwdm.org/Publications/pdf/Feral%20Pig/Txferalhogs.pdf

McClendon, T. 1991. Preliminary description of the vegetation of South Texas exclusive of the Coastal Saline Zones. Texas Journal of Science, 43:13-32.

McGinty A., D. N. Ueckert. 2001. The Brush Busters success story. Rangelands, 23:3-8.

McLendon, T. 1991. Preliminary description of the vegetation of south Texas exclusive of coastal saline zones. Texas Journal of Science, 43:13-32.

Norwine, J. 1978. Twentieth-century semiarid climates and climatic fluctuations in Texas and northeastern Mexico. Journal of Arid Environments, 1:313-325.

Norwine, J. and R. Bingham. 1986. Frequency and severity of droughts in South Texas: 1900-1983, 1-17. In Livestock and wildlife management during drought. Edited by R. D. Brown. Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Kingsville, TX.

Olmsted, F. L. 1857. A journey through Texas, or a saddle trip on the Southwest frontier: with a statistical appendix. Dix, Edwards, and co., New York, London.

Prichard, D. 1998. A User Guide to Assessing Proper Functioning Condition and the Supporting Science for Lentic Areas. Bureau of Land Management. National Applied Resource Sciences Center, CO.

Rappole, J. H. and G. W. Blacklock. 1994. A field guide: Birds of Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Rhyne, M. Z. 1998. Optimization of wildlife and recreation earnings for private landowners. M. S. Thesis, Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Kingsville, TX.

Schindler, J. R. and T. E. Fulbright. 2003. Roller chopping effects on Tamaulipan scrub community composition. Journal of Range Management, 56:585-590.

Schmidley, D. J. 1983. Texas mammals east of the Balcones Fault zone. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Scifres C. J., W. T. Hamilton, J. R. Conner, J. M. Inglis, and G. A. Rasmussen. 1985. Integrated Brush Management Systems for South Texas: Development and Implementation. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, College Station, TX.

Scifres, C. J. and W. T. Hamilton. 1993. Prescribed burning for brushland management: the South Texas example. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX.

Scifres, C. J. 1975. Systems for improving McCartney rose infested coastal prairie rangeland. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin MP 1225.

Smeins, F. E., S. Fuhlendorf, and C. Taylor, Jr. 1997. Environmental and Land Use Changes: A Long Term Perspective. In Juniper Symposium, 1-21. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station.

Smeins, F. E., D. D. Diamond, and W. Hanselka. 1991. Coastal prairie, 269-290. In Ecosystems of the World: Natural Grasslands. Edited by R. T. Coupland. Elsevier Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Soil Survey Staff, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Soil Survey Geographic (SSURGO) Database.

Snyder, R. A. and C. L. Boss. 2002. Recovery and stability in barrier island plant communities. Journal of Coastal Research, 18:530-536.

Stiles, H. R., ed. 1906. Joutel’s journal of La Salle’s last voyage, 1686-1687. Joseph McDonough, Albany, NY.

Stringham, T. K., W. C. Krueger, and P. L. Shaver. 2001. State and transition modeling: and ecological process approach. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):106-113.

Texas A&M Research and Extension Center. 2000. Native Plants of South Texas http://uvalde.tamu.edu/herbarium/index.html.

Texas Agriculture Experiment Station. 2007. Benny Simpson’s Texas Native Trees http://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/ornamentals/natives/.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 2007. List of White-tailed Deer Browse and Ratings. District 8.

Tharp, B. C. 1926. Structure of Texas Vegetation east of the 98th meridian. Bulletin 2606. University of Texas, Austin. TX.

Thurow, T. L. 1991. Hydrology and Erosion. In: Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heitschmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Urbatsch, L. 2000. Chinese tallow tree (Triadica sebifera (L.) Small. USDA-NRCS Plant Guide.

USDA-NRCS Plant Database. 2018. https://plants.usda.gov/.

Van’t Hul, J. T., R. S. Lutz and N. E. Mathews. 1997. Impact of prescribed burning on vegetation and bird abundance on Matagorda Island, Texas. Journal of Range Management, 50:346-360.

Vines, R. A. 1984. Trees of Central Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Wade, D. D., B. L. Brock, P. H. Brose, J. B. Grace, G. A. Hoch, and W. A. Patterson III. 2000. Fire in Eastern ecosystems. In Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora. Edited by. J. K. Brown and J. Kaplers. United States Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden, UT.

Weltz, M. A. and W. H. Blackburn. 1995. Water budget for south Texas rangelands. Journal of Range Management, 48:45-52.

Whittaker, R. H., L. E. Gilbert, and J. H. Connell. 1979. Analysis of a two-phase pattern in a mesquite grassland, Texas. Journal of Ecology, 67:935-52.

Wright, B. D., R. K. Lyons, J. C. Cathey, and S. Cooper. 2002. White-tailed deer browse preferences for South Texas and the Edwards Plateau. Texas Cooperative Extension Bulletin B-6130.

Wright, H.A. and A.W. Bailey. 1982. Fire Ecology: United States and Southern Canada. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Approval

Bryan Christensen, 9/19/2023

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 09/23/2023 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Prolonged drought coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Removal of native vegetation followed by soil disturbance and seeding of non-native species |

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of natural disturbance return intervals |

| T2A | - | Removal of woody vegetation followed by extensive soil disturbance and seeding of non-native species |

| T3A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time |