Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R083BY019TX

Gray Sandy Loam

Last updated: 9/19/2023

Accessed: 02/27/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

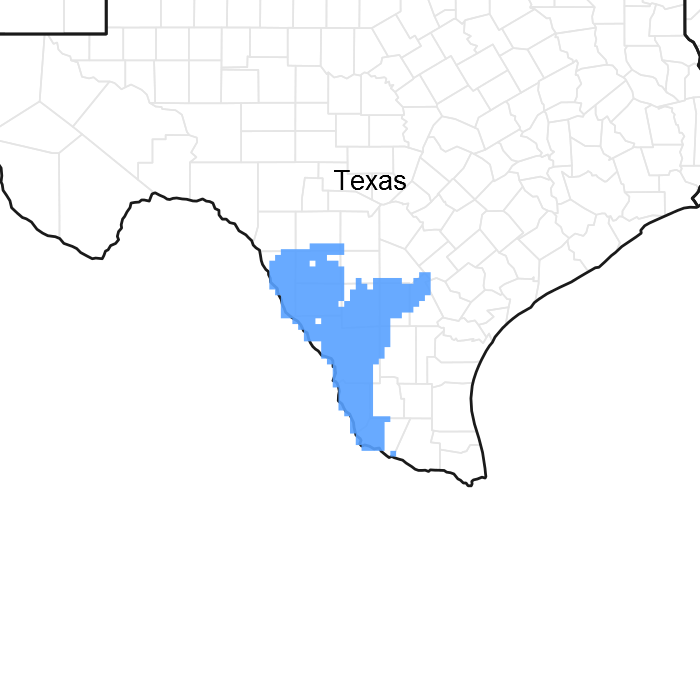

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 083B–Western Rio Grande Plain

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 83B It makes up about 9,285 square miles (24,060 square kilometers). The border towns of Del Rio, Eagle Pass, Laredo, and Zapata are in this MLRA. Interstate 35 crosses the area just north of Laredo. The Amistad National Recreation Area is just outside this MLRA, northwest of Del Rio, and the Falcon State Recreation Area is southeast of Laredo. Laughlin Air Force Base is just east of Del Rio. This area is comprised of inland, dissected coastal plains.

Classification relationships

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006.

-Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 83B

Ecological site concept

The Gray Sandy Loam refers to the gray-colored, sandy loam surfaces found on the ecological site. High amounts of calcium carbonates in the upper soil profile are responsible for the gray colors and alkalinity.

Associated sites

| R083BY018TX |

Clay Flat |

|---|---|

| R083BY004TX |

Shallow Sandy Loam |

| R083BY005TX |

Shallow |

| R083BY012TX |

Ramadero |

| R083BY025TX |

Clay Loam |

| R083BY003TX |

Gravelly Ridge |

| R083BY011TX |

Claypan Prairie |

Similar sites

| R083AY019TX |

Gray Sandy Loam |

|---|---|

| R083CY019TX |

Gray Sandy Loam |

| R083DY019TX |

Gray Sandy Loam |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Bernardia myricifolia |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Heteropogon contortus |

Physiographic features

Sites were formed on nearly level to gently sloping interfluves and ridges on the inland, dissected Coastal Plains. Surfaces are linear to convex. Slope ranges from 0 to 5 percent but are mostly less than 3 percent. Elevation is 150 to 880 feet.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Coastal plain

> Interfluve

(2) Coastal plain > Ridge |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to medium |

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 150 – 880 ft |

| Slope | 5% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

MLRA 83B mainly has a subtropical steppe climate along the Rio Grande River and subtropical subhumid climates in La Salle and McMullen counties. Winters are dry and mild and the summers are hot. Tropical maritime air masses predominate throughout spring, summer and fall. Modified polar air masses exert considerable influence during winter, creating a continental climate characterized by large variations in temperature. Peak rainfall occurs late in spring and a secondary peak occurs early in fall. Most heavy thunderstorm activities occur during the summer months. July is hot and dry with little weather variations. Rainfall increases again in late August and September as tropical disturbances increase and become more frequent as the storms dissipate. Tropical air masses from the Gulf of Mexico dominate during the spring, summer and fall. Prevailing winds are southerly to southeasterly throughout the year except in December when winds are predominately northerly.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 231-321 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 313-365 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 20 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 214-365 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 260-365 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 19-21 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 270 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 340 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 20 in |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) FALCON DAM [USC00413060], Roma, TX

-

(2) LAREDO 2 [USC00415060], Laredo, TX

-

(3) CATARINA [USC00411528], Asherton, TX

-

(4) CRYSTAL CITY [USC00412160], Crystal City, TX

-

(5) DEL RIO 2 NW [USC00412361], Del Rio, TX

-

(6) EAGLE PASS 3N [USC00412679], Eagle Pass, TX

-

(7) ZAPATA 1 S [USC00419976], Zapata, TX

-

(8) DEL RIO INTL AP [USW00022010], Del Rio, TX

Influencing water features

Water features do not influence this site.

Wetland description

N/A.

Soil features

The soil are moderately deep to very deep, moderate to moderately slowly permeable over weakly to strongly cemented sandstone. The site gets its name from the gray colors in the soil resulting from calcium carbonates, making the soils alkaline. Soil series correlated to this site include: Aguillares, Choke, Copita, Lenocita, and Tonio.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

sedimentary rock

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Fine sandy loam (2) Sandy clay loam (3) Silty clay loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Fine-loamy (2) Fine-silty |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate to moderately slow |

| Soil depth | 20 – 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 1% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

4 – 7 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

1 – 35% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

4 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

10 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

7.4 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

10% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

1% |

Ecological dynamics

The accounts of early explorers and settlers suggest that the Rio Grande Plains was likely a vast mosaic of open grassland, savannah, and shrubland. While moving in 1691 out of Maverick County and into Zavala County, Don Domingo de Teran found after crossing the Nueces River “the country was level and covered with mesquites and cats’ claw.” In 1849, Michler described south Texas as “concerning the land both on the Frio and the Leona, from these rivers back, that it may be divided into four parallel strips-the first, next to the river, consisting of heavy timber, and a heavy black soil, the second, a mesquite flat, of small width, and the soil of a lighter nature, and very fertile; the third, a range of low hills, covered with loose stones, and thick chaparral; the fourth, a wide-open prairie.” Lehman indicates, “thus while it is quite true that the Rio Grande Plains once had fewer woody plants and more grass than now, it is also true that an ample seed stock of shrubs and trees has been widely distributed for as long as man has known.” The vegetation structure likely varied from place-to-place depending on topography, soil properties, and time since the last major disturbance.

Large numbers of domestic livestock grazed South Texas as early as the mid-1700’s. Formal deeds to properties from the Spanish and Mexican governments came in the late 1760’s with much larger blocks granted in the decades to follow. Lehman indicated, “in 1757, the official Spanish census showed residents of Camargo and Reynosa in the lower Rio Grande owning over 90,000 sheep and goats. By way of contrast, combined numbers of cattle, oxen, horses, mules and burros were less than 16,000.” By the mid-1800’s, according to Lehman’s figures from the U. S. Census of 1889, “there were a minimum of 1,644,268 sheep-fully 45 percent of Texas total population, grazing south of the Nueces River.” According to Inglis, “the Rio Grande Plains had the four-leading sheep producing counties in the state and ten of the top fifteen sheep producing counties were in South Texas. The peak decade was 1880 to 1890, at times exceeding two million head.” These domestic animals were in addition to bison, antelope, deer, and large herds of wild horses. It is obvious from early accounts, that much of the Rio Grande Plains was periodically grazed hard by both domestic animals and wild populations as early as the early to mid-1700’s. It may be that overgrazing by sheep and goats could have suppressed the many shrubs, reduced shrub canopy, and arrested shrub seedlings.

With the arrival of European man, the South Texas area was fenced and, in many instances, stocked beyond its capability to sustain forage. This overstocking led to a reduced fire frequency and intensity, creating an opportunity for woody shrubs to increase across the landscape. As the natural graze-rest cycles were altered and stocking rates continued to exceed the natural carrying capacity of the land, midgrasses were replaced by shortgrasses and the ground cover was opened so additional annual and perennial forbs also increased. Drought certainly enhanced this effect. As prolonged overgrazing continued, shrub cover increased. Shortgrasses became dominant and forage production decreased. This change in plant cover and structure further decreased fire frequency and intensity, favoring shrub establishment and dominance.

The plant communities of this site are dynamic varying in relation to fire, periodic drought, and wet cycles. Periodic fires were set by either Native Americans or started naturally by lightning. Fire did not play as important a role on this site as in deeper more productive sites due to lower production of grasses to burn. Because of large amounts of gravel in the soil, available water holding capacity is greatly reduced. This causes highly variable forage production and minimal grass production during dry years. The historic community of this site was influenced to some extent by periodic grazing by herds of buffalo and wild horses. Herds of buffalo and wild horses would come into an area, graze it down, and then not come back for many months or even years depending upon the availability of water. This long deferment period allowed recovery of the grasses and forbs which served as fuel load. More than likely, fire occurred following years of good rainfall followed by a dry season. The fire frequency for this area is interpreted to be four to six years (Frost, 1998).

Presently, the Gray Sandy Loam is a community of woody shrubs exceeding 50 percent canopy, with the interspaces dominated by shortgrasses such as common curly mesquite (Hilaria berlangeri), fall witchgrass (Digitaria cognata), Hall’s panicum (Panicum hallii), perennial threeawn (Aristida purpurea), and tumblegrass (Schedonnardus paniculatus). If drought and/or grazing denude the site, soils will cap over and infiltration of rainfall will be reduced significantly making the site much more droughty. When in this condition, this site recovers very slowly, and mechanical manipulation will be required to reduce shrub canopy and break the soil crust.

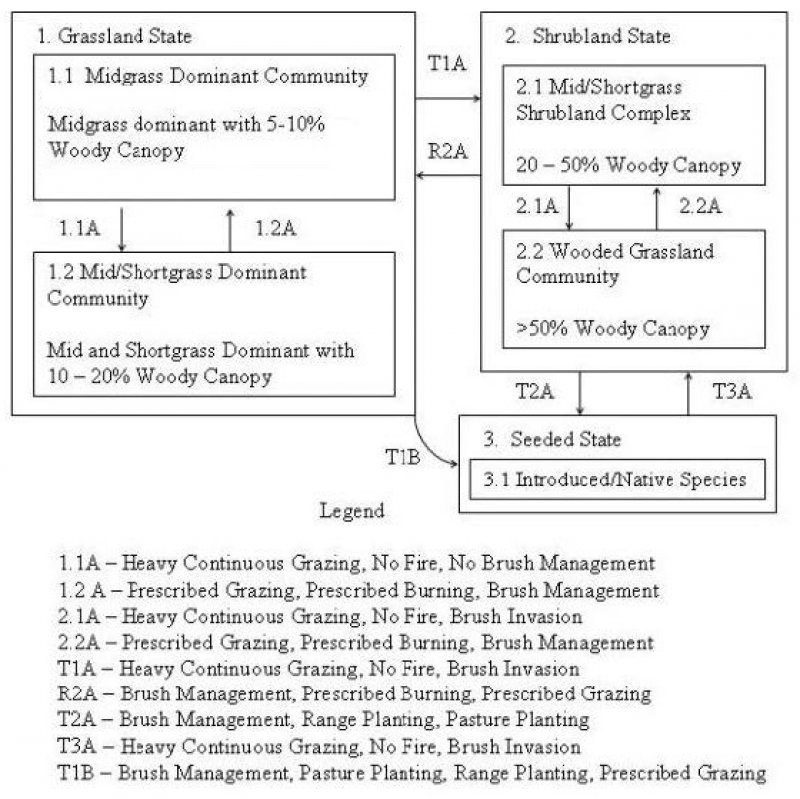

State and transition model

Figure 8. STM

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Excessive soil disturbance followed by seeding improved forage species |

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of historic disturbance return intervals |

| T2A | - | Excessive soil disturbance followed by seeding improved forage species |

| T3A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Grassland

Dominant plant species

-

multiflower false Rhodes grass (Trichloris pluriflora), grass

-

tanglehead (Heteropogon contortus), grass

Community 1.1

Midgrass Dominant

The reference community for the Gray Sandy Loam is an open grassland dominated by midgrasses, perennial forbs, and interspersed with occasional woody shrubs. Dominant midgrasses include multi-flowered false rhodesgrass, tanglehead, plains bristlegrass, Arizona cottontop, and silver bluestem. There are shortgrasses present but in limited amounts. Perennial forbs include bush sunflower, orange zexmenia, daleas, snoutbeans, and bundleflowers. Scattered woody plants occurr making up less than 10 percent of the total composition. These included guajillo, granjeno, cenizo, wolfberry, blackbrush acacia and many others.

Figure 9. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 800 | 2300 | 3300 |

| Forb | 150 | 200 | 300 |

| Shrub/Vine | 100 | 150 | 200 |

| Tree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1050 | 2650 | 3800 |

Figure 10. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4800, Midgrass Dominant Community. Warm-season midgrasses with forbs and shrubs..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 6 | 2 |

Community 1.2

Midgrass/Shortgrass Dominant

Figure 11. 1.2 Midgrass/Shortgrass Dominant Community

This community is resilient, still influenced of fire, and can easily be transitioned back to community 1.1. This community is very stable and is often maintained for wildlife purposes. Continued heavy grazing coupled with drought cycles has caused the dominant midgrasses to decrease in composition. The opening of the midgrass canopy causes shortgrasses, forbs and woody species to increase. Reduction in stocking rates, periodic rest, and increased fire frequency will maintain this community, or even transition back to the reference community. But, if over grazing continues, midgrasses will continue to decline, fire frequency and intensity will decrease, and the plant community will continue towards the Shrubland State. Such species as tanglehead, multi-flowered false Rhodes grass, Arizona cottontop, and plains bristlegrass diminish and are replaced by species like pink pappusgrass, hooded windmillgrass, and perennial three-awns. Short grasses such as curly mesquite, Hall’s panicum, tumble windmillgrass, and sand dropseed also increase.

Figure 12. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 600 | 2000 | 2800 |

| Forb | 175 | 250 | 350 |

| Shrub/Vine | 175 | 225 | 300 |

| Tree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 950 | 2475 | 3450 |

Figure 13. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4800, Midgrass Dominant Community. Warm-season midgrasses with forbs and shrubs..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 6 | 2 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

A shift to the 1.2 Community occurs if the Midgrass Community is weakened by excessive leaf removal. Drought hastens the process. A reduction in midgrass also corresponds in a reduction of fuel loading needed for fire to effectively suppress woody species.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Managerial activities that restore the hydrologic cycle, the energy capture by midgrasses, and ground cover will move the 1.2 Community toward the Midgrass Community (1.1). Utilizing historic ecological disturbances such as herbivory and fire in constructive amounts are needed. Selective brush management may also be needed.

State 2

Shrubland

Dominant plant species

-

guajillo (Acacia berlandieri), shrub

-

spiny hackberry (Celtis ehrenbergiana), shrub

Community 2.1

Mid/Shortgrass Shrubland Complex

The Mid/Shortgrass Shrubland Complex represents a community where thresholds have been crossed. Continued heavy grazing, no rest, greatly reduced fire frequency, and increasing shrub canopy cover have altered this plant community drastically. Midgrasses, though still present, are relegated to a position within the thorny shrubs. Interspaces between shrubs are dominantly species of hooded windmillgrass, sand dropseed, curly mesquite, and Hall’s panicum. Water, energy, and mineral cycles are drastically altered. Although rainfall still infiltrates within the shrub community, woody plants harvest the water, limiting the amount available for herbaceous production. In this state, fire is rare to non-existent due to decreased fine fuel loads and absence of litter accumulation. In above normal rainfall years, some fine fuel loads may build in the shrub interspaces allowing mid-summer lightning fires to burn. These wild fires will be of much less intensity, will essentially burn only in the interspaces and will do little to damage shrub canopy. In most instances, prescribed burning is not feasible due to decreased fuel loading and discontinuous fuel beds.

Figure 14. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 300 | 1300 | 1800 |

| Shrub/Vine | 300 | 400 | 500 |

| Forb | 300 | 400 | 500 |

| Tree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 900 | 2100 | 2800 |

Figure 15. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4801, Mid/Shortgrasses Shrubland Community. Mid and shortgrasses with forbs and 20-50% woody canopy..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 6 | 2 |

Community 2.2

Wooded Grassland

Figure 16. 2.2 Wooded Grassland Community

The Wooded Grassland Community (2.2) has woody canopies exceeding 50, and often 80, percent. Midgrasses are found only within thorny shrubs and the few interspaces are dominated by shortgrasses. Fire on the site is almost totally non-existent. This community can be brought back to Community 2.1 or even the Grassland State (1) but not without significant restoration efforts. Because of the diverse woody plant community, this site in this community is most often manipulated by roller-chopping to enhance it for white-tailed deer, northern bobwhite, and/or scaled quail. This is a very good wildlife site in this state if the woody plant community is manipulated in some pattern and grazing use is very carefully managed. Wildlife enterprises are commonly utilize this community.

Figure 17. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 100 | 500 | 900 |

| Shrub/Vine | 500 | 800 | 900 |

| Forb | 200 | 350 | 500 |

| Tree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 800 | 1650 | 2300 |

Figure 18. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4802, Wooded Grassland Community. Wooded Grassland Community with 50 to 80% woody canopy cover..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 1 | 5 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 10 | 13 | 15 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

A shift to the to Community 2.2 occurs if brush management is not accomplished. Drought hastens the process. A lack of brush management allows existing brush to gain in stature. Seedlings are introduced through droppings from livestock and wildlife. A reduction in midgrass also corresponds in a reduction of fuel loading needed for fire to effectively suppress woody species, although fire is a questionable at this point.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Managerial activities that restore the hydrologic cycle, such as the energy captured by midgrasses, and restored ground cover will tend to move the Community 2.2 toward the Mid/Shortgrass Shrubland Complex (2.1). Selective brush management is needed to accomplish the desired canopy level and spatial arrangement of woody species. Integrated brush management and utilizing historic ecological disturbances such as herbivory and fire in are needed to maintain the desired brush densities. The time to shift back to the 20 to 50 percent canopy is dependent upon favorable growing conditions and could take three to five years.

Community 3.1

Introduced and Native Seeding

The Seeded State is attained by mechanical manipulation of the woody plant community either by rhome disking or by root-plowing. Following mechanical control, the site has traditionally been seeded to buffelgrass (Cenchrus ciliaris). Historically, native-grass mixtures have been used very little in South Texas due to the lack of availability. Following mechanical management, woody plants will re-establish. The woody plant community that returns will be limited in species diversity and little will be desirable for. The Seeded State can be maintained for long periods of time with the use of fire, periodic brush management, and the use of prescribed grazing.

Figure 19. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 9. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 900 | 2400 | 3400 |

| Forb | 150 | 200 | 300 |

| Shrub/Vine | 40 | 70 | 100 |

| Tree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1090 | 2670 | 3800 |

Figure 20. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4762, Introduced Grass Community. Planted into introduced grasses for pasture planting..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 0 |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

The Grassland State will cross a threshold to Shrubland (State 2) with abusive grazing and without brush management or fire. Severe drought is also a significant factor to accelerate this crossing of a threshold. In State 2 more rainfall is being utilized by woody plants than the herbaceous plants. Because of the increased canopy, sunlight is being captured by the woody plants and converted to energy instead of the herbaceous plants.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The transition to the Converted Land State is triggered by major ground disturbing mechanical treatment and planting to native or introduced forages. Planting is usually done following brush management.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Brush management is the key driver in restoring State 2 back to the Grassland State (1). Reduction in woody canopy below 20 percent will take large energy inputs depending on the canopy cover. A prescribed grazing plan and prescribed burning plan will keep the state functioning.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

The transition to the Seeded State is triggered by major ground disturbing mechanical treatment and planting to native or introduced forages. Planting is usually done following brush management.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

The transition from the Seeded State to the Shrubland State is triggered by neglect or no management over long periods of time. Shrubs re-establish from the seed bank and introduction from wildlife and livestock. A complete return to a previous state is not possible if adapted non-native plants have been established.

Additional community tables

Table 10. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 0 | Midgrass | 160–660 | ||||

| 1 | Midgrasses | 320–1320 | ||||

| multiflower false Rhodes grass | TRPL3 | Trichloris pluriflora | 200–700 | – | ||

| silver beardgrass | BOLAT | Bothriochloa laguroides ssp. torreyana | 20–300 | – | ||

| large-spike bristlegrass | SEMA5 | Setaria macrostachya | 30–300 | – | ||

| Arizona cottontop | DICA8 | Digitaria californica | 50–200 | – | ||

| 2 | Mid/Shortgrasses | 160–660 | ||||

| pink pappusgrass | PABI2 | Pappophorum bicolor | 50–300 | – | ||

| hooded windmill grass | CHCU2 | Chloris cucullata | 30–200 | – | ||

| plains lovegrass | ERIN | Eragrostis intermedia | 20–100 | – | ||

| lovegrass tridens | TRER | Tridens eragrostoides | 20–100 | – | ||

| 3 | Mid/Shortgrasses | 80–330 | ||||

| purple threeawn | ARPU9 | Aristida purpurea | 0–150 | – | ||

| marsh bristlegrass | SEPA10 | Setaria parviflora | 0–100 | – | ||

| Texas bristlegrass | SETE6 | Setaria texana | 10–100 | – | ||

| slim tridens | TRMUM | Tridens muticus var. muticus | 5–50 | – | ||

| 4 | Shortgrasses | 80–330 | ||||

| curly-mesquite | HIBE | Hilaria belangeri | 30–150 | – | ||

| Hall's panicgrass | PAHA | Panicum hallii | 5–100 | – | ||

| sand dropseed | SPCR | Sporobolus cryptandrus | 5–50 | – | ||

| fall witchgrass | DICO6 | Digitaria cognata | 0–50 | – | ||

| Madagascar dropseed | SPPY2 | Sporobolus pyramidatus | 5–10 | – | ||

| slender grama | BORE2 | Bouteloua repens | 5–10 | – | ||

| Texas grama | BORI | Bouteloua rigidiseta | 1–5 | – | ||

| red grama | BOTR2 | Bouteloua trifida | 1–5 | – | ||

| tumble windmill grass | CHVE2 | Chloris verticillata | 0–5 | – | ||

| sand crabgrass | DIAR7 | Digitaria arenicola | 0–5 | – | ||

| southern crabgrass | DICI | Digitaria ciliaris | 0–5 | – | ||

| knot grass | SEREF | Setaria reverchonii ssp. firmula | 0–5 | – | ||

| gummy lovegrass | ERCU | Eragrostis curtipedicellata | 0–5 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 5 | Forbs | 75–150 | ||||

| awnless bushsunflower | SICA7 | Simsia calva | 10–50 | – | ||

| whitemouth dayflower | COER | Commelina erecta | 5–30 | – | ||

| Riddell's dozedaisy | APRI | Aphanostephus riddellii | 5–20 | – | ||

| violet wild petunia | RUNU | Ruellia nudiflora | 5–10 | – | ||

| Gregg's tube tongue | JUPI5 | Justicia pilosella | 5–10 | – | ||

| trailing krameria | KRLA | Krameria lanceolata | 0–5 | – | ||

| 6 | Forbs | 45–90 | ||||

| Texas sleepydaisy | XATE | Xanthisma texanum | 5–20 | – | ||

| yellow puff | NELU2 | Neptunia lutea | 0–15 | – | ||

| wild tantan | DEVI3 | Desmanthus virgatus | 1–15 | – | ||

| hoary milkpea | GACA | Galactia canescens | 0–10 | – | ||

| littleleaf sensitive-briar | MIMI22 | Mimosa microphylla | 0–10 | – | ||

| prairie clover | DALEA | Dalea | 0–10 | – | ||

| American snoutbean | RHAM | Rhynchosia americana | 0–10 | – | ||

| globemallow | SPHAE | Sphaeralcea | 1–10 | – | ||

| 7 | Forbs | 30–60 | ||||

| Forb, perennial | 2FP | Forb, perennial | 10–20 | – | ||

| fanpetals | SIDA | Sida | 5–15 | – | ||

| woody crinklemat | TICA3 | Tiquilia canescens | 5–10 | – | ||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 5–10 | – | ||

| Texas crownbeard | VEMI | Verbesina microptera | 0–5 | – | ||

| bristleleaf pricklyleaf | THTE7 | Thymophylla tenuiloba | 1–5 | – | ||

| Texas Indian mallow | ABFR3 | Abutilon fruticosum | 1–5 | – | ||

| prairie false foxglove | AGHE4 | Agalinis heterophylla | 0–5 | – | ||

| weakleaf bur ragweed | AMCO3 | Ambrosia confertiflora | 0–5 | – | ||

| prairie broomweed | AMDR | Amphiachyris dracunculoides | 0–5 | – | ||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 1–5 | – | ||

| desert goosefoot | CHPR5 | Chenopodium pratericola | 0–5 | – | ||

| Texas bindweed | COEQ | Convolvulus equitans | 0–5 | – | ||

| broom snakeweed | GUSA2 | Gutierrezia sarothrae | 1–5 | – | ||

| slimleaf heliotrope | HETO | Heliotropium torreyi | 0–5 | – | ||

| cheeseweed mallow | MAPA5 | Malva parviflora | 0–5 | – | ||

| povertyweed | MONOL | Monolepis | 0–5 | – | ||

| Santa Maria feverfew | PAHY | Parthenium hysterophorus | 0–5 | – | ||

| cutleaf groundcherry | PHAN5 | Physalis angulata | 1–5 | – | ||

| smartweed leaf-flower | PHPO3 | Phyllanthus polygonoides | 0–5 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 8 | Shrubs/Vines | 100–200 | ||||

| mouse's eye | BEMY | Bernardia myricifolia | 30–50 | – | ||

| Texas barometer bush | LEFR3 | Leucophyllum frutescens | 20–50 | – | ||

| spiny hackberry | CEEH | Celtis ehrenbergiana | 20–40 | – | ||

| guajillo | ACBE | Acacia berlandieri | 20–40 | – | ||

| catclaw acacia | ACGRW | Acacia greggii var. wrightii | 10–20 | – | ||

| blackbrush acacia | ACRI | Acacia rigidula | 10–20 | – | ||

| Texan goatbush | CAERT | Castela erecta ssp. texana | 10–20 | – | ||

| Texas persimmon | DITE3 | Diospyros texana | 10–20 | – | ||

| Berlandier's wolfberry | LYBE | Lycium berlandieri | 10–20 | – | ||

| Texas kidneywood | EYTE | Eysenhardtia texana | 10–20 | – | ||

| pricklypear | OPUNT | Opuntia | 10–20 | – | ||

| lotebush | ZIOB | Ziziphus obtusifolia | 5–20 | – | ||

| Texas paloverde | PATE10 | Parkinsonia texana | 5–15 | – | ||

| shrubby blue sage | SABA5 | Salvia ballotiflora | 5–15 | – | ||

| Texas babybonnets | COAX | Coursetia axillaris | 5–15 | – | ||

| Brazilian bluewood | COHO | Condalia hookeri | 5–15 | – | ||

| algerita | MATR3 | Mahonia trifoliolata | 5–10 | – | ||

| leatherstem | JADI | Jatropha dioica | 5–10 | – | ||

| coyotillo | KAHU | Karwinskia humboldtiana | 5–10 | – | ||

| crown of thorns | KOSP | Koeberlinia spinosa | 5–10 | – | ||

| West Indian shrubverbena | LAUR2 | Lantana urticoides | 5–10 | – | ||

| catclaw acacia | ACGRG3 | Acacia greggii var. greggii | 5–10 | – | ||

| Christmas cactus | CYLE8 | Cylindropuntia leptocaulis | 5–10 | – | ||

| lime pricklyash | ZAFA | Zanthoxylum fagara | 5–10 | – | ||

| desert yaupon | SCCU4 | Schaefferia cuneifolia | 1–5 | – | ||

| yucca | YUCCA | Yucca | 1–5 | – | ||

| littleleaf sumac | RHMI3 | Rhus microphylla | 1–5 | – | ||

| Rio Grande beebrush | ALMA9 | Aloysia macrostachya | 0–5 | – | ||

| Texas swampprivet | FOAN | Forestiera angustifolia | 1–5 | – | ||

| Texan hogplum | COTE6 | Colubrina texensis | 0–5 | – | ||

| clapweed | EPAN | Ephedra antisyphilitica | 1–5 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

As a historic tall/midgrass prairie, this site was occupied by bison, antelope, deer, quail, turkey, and dove. This site was also used by many species of grassland songbirds, migratory waterfowl, and coyotes. This site now provides forage for livestock and is still used by quail, dove, migratory waterfowl, grassland birds, coyotes, and deer.

Feral hogs (Sus scrofa) can be found on most ecological sites in Texas. Damage caused by feral hogs each year includes, crop damage by rutting up crops, destroyed fences, livestock watering areas, and predation on native wildlife. Feral hogs have few natural predators, thus allowing their population to grow to high numbers.

Wildlife habitat is a complex of many different plant communities and ecological sites across the landscape. Most animals use the landscape differently to find food, shelter, protection, and mates. Working on a conservation plan for the whole property, with a local professional, will help managers make the decisions that allow them to realize their goals for wildlife and livestock.

Grassland State (1): This state provides the maximum amount of forage for livestock such as cattle. It is also utilized by deer, quail and other birds as a source of food. When a site is in the reference plant community phase (1.1) it will also be used by some birds for nesting, if other habitat requirements like thermal and escape cover are near.

Tree/Shrubland (2): This state can be maintained to meet the habitat requirements of cattle and wildlife. Land managers can find a balance that meets their goals and allows them flexibility to manage for livestock and wildlife. Forbs for deer and birds like quail will be more plentiful in this state. There will also be more trees and shrubs to provide thermal and escape cover for birds as well as cover for deer.

Seeded State (3): The quality of wildlife habitat this site will produce is extremely variable and is influenced greatly by the timing of rain events. This state is often manipulated to meet landowner goals. If livestock production is the main goal, it can be converted to pastureland. It can also be planted to a mix of grasses and forbs that will benefit both livestock and wildlife. A mix of forbs in the pasture could attract pollinators, birds and other types of wildlife. Food plots can also be planted to provide extra nutrition for deer.

This rating system provides general guidance as to animal preference for plant species. It also indicates possible competition between kinds of herbivores for various plants. Grazing preference changes from time to time, especially between seasons, and between animal kinds and classes. Grazing preference does not necessarily reflect the ecological status of the plant within the plant community. For wildlife, plant preferences for food and plant suitability for cover are rated. Refer to habitat guides for a more complete description of a species habitat needs.

Hydrological functions

The grassland and the shrubland communities on this site use all the water from rainfall events. Research has shown that the evapotranspiration rate on the grassland and the shrubland is nearly the same. Very little water could be harvested from this site if the woody plant community is replaced by a grass-dominated community.

Recreational uses

White-tailed deer, quail, javelina, and feral hogs are hunted on the site. Bird watching may also be done.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented was derived from the revised Range Site, literature, limited NRCS clipping data (417s), field observations, and personal contacts with range-trained personnel.

Other references

Archer, S. 1995. Herbivore mediation of grass-woody plant interactions. Tropical Grasslands, 29:218-235.

Archer, S. 1995. Tree-grass dynamics in a Prosopis-thornscrub savanna parkland: reconstructing the past and predicting the future. Ecoscience, 2:83-99.

De Leon, A. 2003. Itineraries of the De Léon Expeditions of 1689 and 1690. In Spanish Exploration in the Southwest, 1542-1706. Edited by H. E. Bolton. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY.

Dillehay T. 1974. Late quaternary bison population changes on the Southern Plains. Plains Anthropologist, 19:180-96.

Duaine, C. L. 1971. Caverns of Oblivion. Packrat Press, Oak Harbor, WA.

Everitt, J. H., D. L. Drawe, and R. I. Leonard. 2002. Trees, Shrubs, and Cacti of South Texas. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, TX.

Everitt, J. H., D. L. Drawe, and R. I. Lonard. 1999. Field Guide to the Broad-Leaved Herbaceous Plants of South Texas. Texas Tech University Press. Lubbock, TX.

Frost, C. C. 1998. Presettlement fire frequency regimes of the United States: a first approximation. In Fire in ecosystem management: shifting the paradigm from suppression to prescription. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings. 20:70-81.

Gilbert, L. E. 1982. An ecosystem perspective on the role of woody vegetation, especially mesquite, in the Tamaulipan biotic region of South Texas. Proceeding Symposium of the Tamaulipan Biotic Province, Corpus Christi, TX.

Hanselka, W., R. Lyons, and M. Moseley. 2009. Grazing Land Stewardship: A Manual for Texas Landowners. Texas AgriLife Extension Service, College Station, TX.

Hart, C. R., T. Garland, A. C. Barr, B. B. Carpenter, and J.C. Reagor. 2003. Toxic Plants of Texas: Integrated Management Strategies to Prevent Livestock Losses. Texas Cooperative Extension Bulletin B-6103 11-03.

Heitschmidt R. K., Stuth J. W., eds. 1991. Grazing management: an ecological perspective. Timberline Press, Portland, OR.

Inglis, J. M. 1964. A history of vegetation of the Rio Grande Plains. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Bulletin No. 45, Austin, TX.

Lehman, V. W. 1969. Forgotten legions: sheep in the Rio Grande Plains of Texas. Texas Western Press, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX.

McGinty A., D. N. Ueckert. 2001. The Brush Busters success story. Rangelands, 23:3-8.

McLendon T. 1991. Preliminary description of the vegetation of South Texas exclusive of coastal saline zones. Texas Journal of Science, 43: 13-32

Norwine, J. 1978. Twentieth-century semiarid climates and climatic fluctuations in Texas and northeastern Mexico. Journal of Arid Environments, 1:313-325.

Norwine, J. and R. Bingham. 1986. Frequency and severity of droughts in South Texas: 1900-1983, 1-17. In Livestock and wildlife management during drought. Edited by R. D. Brown. Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Kingsville, TX.

Parvin, R. W. 2003. Rio Bravo Resource Conservation and Development. Llanos Mestenos South Texas Heritage Trail. Zapata, TX.

Scifres, C. J. and W. T. Hamilton. 1993. Prescribed burning for brushland management: the South Texas example. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX.

Scifres C. J., W. T. Hamilton, J. R. Conner, J. M. Inglis, and G. A. Rasmussen. 1985. Integrated Brush Management Systems for South Texas: Development and Implementation. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, College Station, TX.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 2007. List of White-tailed Deer Browse and Ratings. District 8.

Thurow, T. L. and J. W. Hester. 1997. How an increase or reduction in juniper cover alters rangeland hydrology. Juniper Symposium Proceedings. Texas A&M University, San Angelo, TX.

Weltz, M. A. and W. H. Blackburn. 1995. Water budget for south Texas rangelands. Journal of Range Management, 48:45-52.

Wright, B. D., R. K. Lyons, J. C. Cathey, and S. Cooper. 2002. White-tailed deer browse preferences for South Texas and the Edwards Plateau. Texas Cooperative Extension Bulletin B-6130.

Contributors

Gary Harris, MSSL, NRCS, Robstown, Texas

Approval

Bryan Christensen, 9/19/2023

Acknowledgments

Reviewers:

Shanna Dunn, RSS, NRCS, Corpus Christi, Texas

Vivian Garcia, RMS, NRCS, Corpus Christi, Texas

Jason Hohlt, RMS, NRCS, Kingsville, Texas

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Vivian Garcia, Zone RMS, NRCS, Corpus Christi, Texas |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | 361-241-0609 |

| Date | 09/17/2007 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

None except following extremely high intensity storms when short flow patterns may appear. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

Few. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

0 to 5 percent bare ground. Small and non-connected areas. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

Few. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Minimal and short. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil stability class anticipated to be 5 to 6 at the surface. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

A-horizon is 0 to 2 inches thick with light, brownish-gray fine sandy loam. Structure is weak, fine, subangular blocky. The surface is hard, friable, slightly sticky, and slightly plastic with few snail shell fragments. The soil is strongly effervescent, moderately alkaline, and has an abrupt smooth boundary. SOM is 0 to 3 percent. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

High canopy, basal cover and density with small interspaces should make rainfall impact negligible. This site has well drained soils, deep with 0 to 3 percent slopes which allow for negligible runoff and erosion. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm-season midgrasses >>Sub-dominant:

Warm-season shortgrasses >Other:

Forbs > Trees/ShrubsAdditional:

Forbs make up five percent species composition while shrubs and trees compose up to five percent species composition. -

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Grasses due to their growth habit will exhibit some mortality and decadence, though very slight. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Litter is dominantly herbaceous. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

1,050 to 3,800 air-dry pounds per acre. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Mesquite, blackbrush, guajillo, lime pricklyash, and cenizo are the primary invaders. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All species should be capable of plant reproduction, except during periods of prolonged drought, heavy natural herbivory, and/or wild fires.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Excessive soil disturbance followed by seeding improved forage species |

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of historic disturbance return intervals |

| T2A | - | Excessive soil disturbance followed by seeding improved forage species |

| T3A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time coupled with excessive grazing pressure |