Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R083DY003TX

Gravelly Ridge

Last updated: 9/21/2023

Accessed: 03/13/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

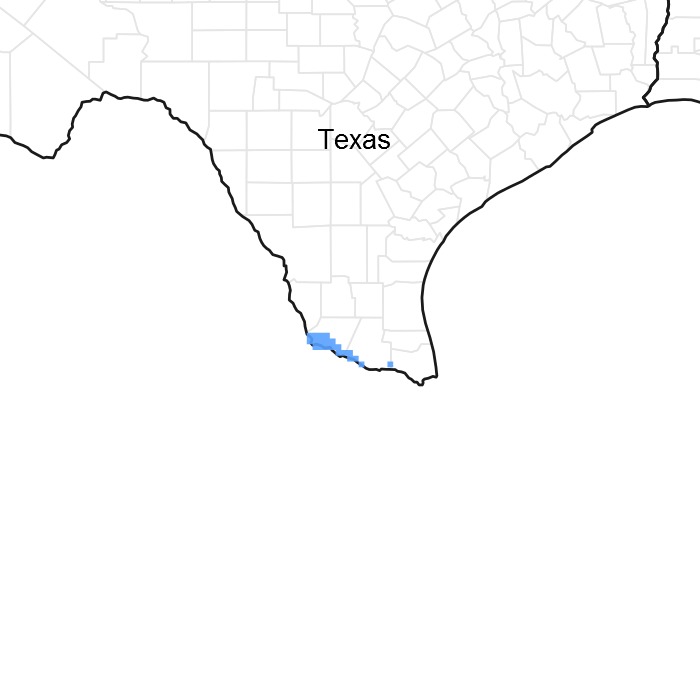

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 083D–Lower Rio Grande Plain

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 83D makes up about 2,500 square miles (6,475 square kilometers). The towns of Brownsville, Edinburg, Harlingen, McAllen, and Raymondville are in this area. U.S. Highways 77 and 281 terminate in Brownsville and McAllen, respectively. The Santa Ana National Wildlife Area is along the Rio Grande in this area.

Classification relationships

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006.

-Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 83D

Ecological site concept

The Gravelly Ridge sites get their name from the gravels that reside in the soil profile. Sites can be very shallow to shallow located on uplands and ridges.

Associated sites

| R083DY007TX |

Lakebed |

|---|---|

| R083DY009TX |

Clayey Bottomland |

| R083DY012TX |

Ramadero |

Similar sites

| R083CY003TX |

Gravelly Ridge |

|---|---|

| R083AY003TX |

Gravelly Ridge |

| R083BY003TX |

Gravelly Ridge |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Acacia berlandieri |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Setaria vulpiseta |

Physiographic features

These soils are nearly level to steep paleoterraces on delta plains. Slope ranges from 1 to 8 percent.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Delta plain

> Paleoterrace

|

|---|---|

| Runoff class | High |

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 100 – 1,000 ft |

| Slope | 1 – 8% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

MLRA 83 has a subtropical, subhumid climate. Winters are dry and warm, and the summers are hot and humid. Tropical maritime air masses predominate throughout spring, summer and fall. Modified polar air masses exert considerable influence during winter, creating a continental climate characterized by large variations in temperature. Peak rainfall occurs late in spring and a secondary peak occurs early in fall. Heavy thunderstorm activities increase in April, May, and June. July is hot and dry with little weather variations. Rainfall increases again in late August and September as tropical disturbances increase and become more frequent. Tropical air masses from the Gulf of Mexico dominate during the spring, summer and fall. Prevailing winds are southerly to southeasterly throughout the year except in December when winds are predominately northerly.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 365 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 22-26 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 271-365 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 21-27 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 348 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 24 in |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) RAYMONDVILLE [USC00417458], Raymondville, TX

-

(2) SANTA ROSA 3 WNW [USC00418059], Edcouch, TX

-

(3) WESLACO [USC00419588], Weslaco, TX

-

(4) HARLINGEN [USC00413943], Harlingen, TX

-

(5) MISSION 4 W [USC00415972], Mission, TX

-

(6) BROWNSVILLE [USW00012919], Brownsville, TX

-

(7) MCALLEN [USC00415701], McAllen, TX

-

(8) MERCEDES 6 SSE [USC00415836], Mercedes, TX

-

(9) MCALLEN MILLER INTL AP [USW00012959], McAllen, TX

-

(10) LA JOYA [USC00414911], Mission, TX

-

(11) RIO GRANDE CITY [USC00417622], Rio Grande City, TX

Influencing water features

Water features are not influential.

Wetland description

N/A.

Soil features

The soils are very shallow to shallow over a petrocalcic horizon. They are well drained, moderately permeable soils that formed in gravelly loamy alluvium over highly calcareous materials. Soil series correlated to this site include: Jimenez and Quemado.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

–

sedimentary rock

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Very gravelly loam (2) Very gravelly sandy loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy-skeletal |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate |

| Soil depth | 8 – 12 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 15 – 20% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-20in) |

1 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-20in) |

10% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-20in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-20in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-20in) |

6.1 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

25 – 30% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

7 – 8% |

Ecological dynamics

The Lower Rio Grande (MLRA 83D) was a disturbance-maintained system. Prior to European settlement (pre-1825), fire and grazing were the two primary forms of disturbance. Grazing by large herbivores included antelope, deer, and small herds of bison. The infrequent but intense, short-duration grazing by these species suppressed woody species and invigorated herbaceous species. The herbaceous savannah species adapted to fire and grazing disturbances by maintaining belowground tissues. Wright and Bailey (1982) report that there are no reliable records of fire frequency for the Rio Grande Plains because there are no trees to carry fire scars from which to estimate fire frequency. Because savannah grassland is typically of level or rolling topography, a natural fire frequency of three to seven years seems reasonable for this area.

Historical accounts prior to 1800 identify grazing by herds of wild horses, followed by heavy grazing by sheep and cattle as settlement progressed. Grazing on early ranches changed natural graze-rest cycles to continuous grazing and stocking rates exceeded the carrying capacity. These shifts in grazing intensity and the removal of rest from the system reduced plant vigor for the most palatable species, which on this site were midgrasses and palatable forbs. Shortgrasses and less palatable forbs began to dominate the site. This shift resulted in lower fuel loads, which reduced fire frequency and intensity. The reduction in fires resulted in an increase in size and density of woody species.

The open grassland in this area supports mid prairie grasses with scattered woody plants, perennial forbs, and legumes on soils in the uplands. Twoflower and fourflower trichloris, plains bristlegrass, and lovegrass tridens are among the dominant grasses on these soils. Desert yaupon, spiny hackberry, and blackbrush are the major woody plants. In bottomland areas, tallgrasses and midgrasses, such as switchgrass, giant sacaton, fourflower trichloris, big sandbur, little bluestem, and southwestern bristlegrass, are dominant. Hackberry, mesquite, elm, and palm trees are the major woody plants. Forbs are important but minor components of all plant communities.

Most of this area is cropland or improved pasture that is extensively irrigated. Large acreages of rangeland are grazed mainly by beef cattle and wildlife. The major crops are cotton, grain sorghum, citrus, onions, cabbage, and other truck crops. Almost all the crops are grown under irrigation. Hunting leases for white-tailed deer, quail, white-winged dove, and mourning dove are an important source of income in the area. Some of the major wildlife species in this area are white-tailed deer, javelina, coyote, fox, bobcat, raccoon, skunk, opossum, jackrabbit, cottontail, turkey, bobwhite quail, scaled quail, white-winged dove, and mourning dove.

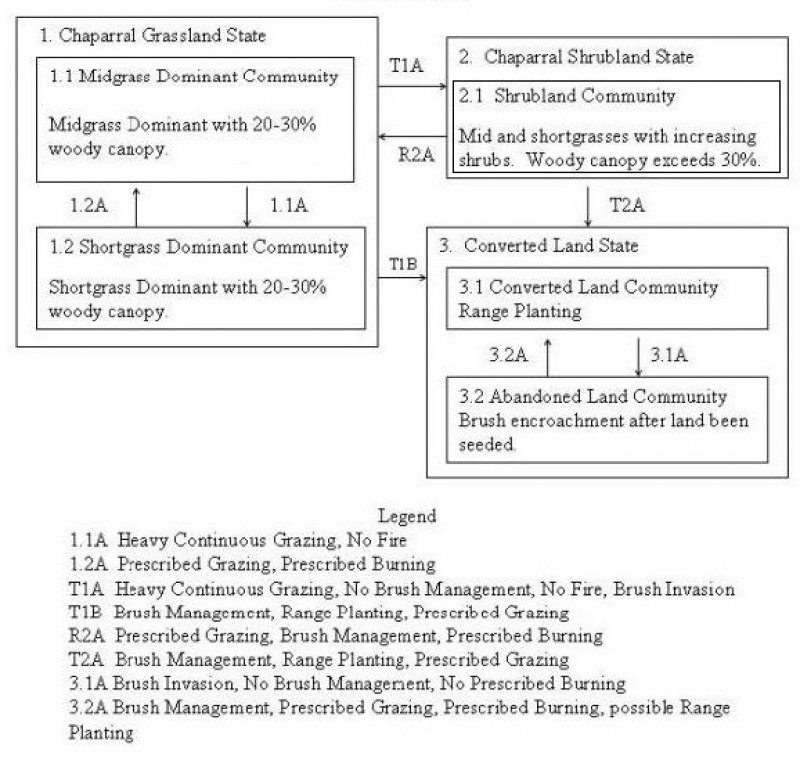

State and transition model

Figure 8. STM

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Extensive soil disturbance followed by seeding improved forage species |

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of historic disturbance return intervals. May be require seeding with native species. |

| T2A | - | Extensive soil disturbance followed by seeding improved forage species |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Chaparral Grassland

Dominant plant species

-

guajillo (Acacia berlandieri), shrub

-

plains bristlegrass (Setaria vulpiseta), other herbaceous

-

slender grama (Bouteloua repens), other herbaceous

Community 1.1

Midgrass Dominant

This community represents the reference plant community. Fire did not play as important a role on this site as on deeper more productive sites. The primary reason is that the inherent grass production on this site is too low for extensive fires except when favorable rainfall provided a surplus of grass fuel. Guajillo is the dominate species of a wide variety of woody shrubs. The predominant grasses for this site are sideoats grama, feather bluestem, bristlegrass species, and Arizona cottontop (Digitaria californica). Arizona cottontop and plains bristlegrass (Setaria macrostachya) are the more opportunistic species on this site and respond quickly to timely rainfall.

Figure 9. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 910 | 1530 | 2160 |

| Shrub/Vine | 400 | 520 | 600 |

| Forb | 70 | 120 | 200 |

| Tree | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| Total | 1400 | 2200 | 3000 |

Figure 10. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4541, Midgrass Dominant Community, 15-30% Canopy. Midgrasses dominate the site with 15-30% woody canopy..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 18 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

Community 1.2

Shortgrass Dominant

This phase of the Chaparral Grassland State (1) still exhibits a chaparral plant structure with the woody species canopy as high as 30 percent. Heavy continuous grazing takes many of the midgrasses out of the site and they are replaced by shortgrasses such as slim tridens, threeawn, red grama, and curlymesquite (Hilaria belangeri).

Figure 11. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 400 | 700 | 1100 |

| Shrub/Vine | 400 | 520 | 600 |

| Forb | 80 | 120 | 170 |

| Tree | 20 | 30 | 30 |

| Total | 900 | 1370 | 1900 |

Figure 12. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4542, Shortgrass Dominant Community, 15-30% canopy. Shortgrasses dominate after midgrasses decline. Woody canopy approaches 15-30%..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 18 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

This phase can still be managed back to the Midgrass Dominant Community (1.1). A prescribed grazing plan, which includes proper stocking rates, will be essential to reverse the trend toward the Shrubland Community (2.1). Once the midgrass species begin to respond, it is possible to use fire when the conditions are right to suppress the brush species. Grazing management alone may not fully restore the reference plant community but can provide one reasonably close.

State 2

Chaparral Shrubland

Dominant plant species

-

blackbrush acacia (Acacia rigidula), shrub

-

guajillo (Acacia berlandieri), shrub

Community 2.1

Shrubland

This plant community is a result of a transition from the Chaparral Grassland State (1) to the Chaparral Shrubland State (2). The herbaceous understory is very limited in production due to the competition for sunlight, water, and nutrients. There is an increase of woody shrubs generally dominated by blackbrush and guajillo. Other woody plants are spiny hackberry (Celtis pallida), guayacan (Guaiacum augustifolium), kidneywood (Eysenhardtia texana), and other acacia species. Water infiltration does occur directly under some of the woody species. Energy flow and nutrient uptake is predominantly through the shrubs. Cool-season annual forbs and grasses are produced by fall and winter rains.

Figure 13. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 250 | 600 | 800 |

| Shrub/Vine | 500 | 600 | 650 |

| Forb | 60 | 100 | 160 |

| Tree | 20 | 30 | 30 |

| Total | 830 | 1330 | 1640 |

Figure 14. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4544, Shrubland Community, 30+% woody canopy. Shrubs dominate the site with heavy continuous grazing and no brush management. Woody canopy exceeds 30%. Grasses are in further decline..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 18 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

Community 3.1

Converted Land

This plant community is developed by applying brush management and seeding. The conversion can actually come from any community where brush needs to be reduced and a seed source added to establish a desired plant community. The area can be seeded to grasses, forbs, or a mix of both. The most common introduced grass species are buffelgrass (Cenchrus ciliaris), kliengrass (Panicum coloratum), and Wilmann lovegrass (Eragrostis superba). It may be desirable to include forbs in these seedings. The decision of species to seed is a management decision based on clearly defined goals for livestock and wildlife. The use of introduced species does provide good forage for cattle and can provide some habitat for wildlife. However, once these species are introduced, it is difficult to remove them should objectives change.

Figure 15. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 900 | 1720 | 2400 |

| Shrub/Vine | 400 | 430 | 600 |

| Forb | 80 | 120 | 170 |

| Tree | 20 | 30 | 30 |

| Total | 1400 | 2300 | 3200 |

Figure 16. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4531, Converted Land - Introduced Grass Seeding. Seeding Coverted Land into Introduced grass species..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

Community 3.2

Abandoned Land

This plant community develops from the Converted Land Community (3.1). Without follow-up brush management, seedlings of shrubs establish themselves and spread. The role of prescribed grazing is to retain grass vigor to compete against seedling establishment and preserve fuel for maintenance burns. Production of the plant types depends on the grazing management that has been applied since seeding, and the canopy of the shrubs invading or spreading on the site. As the canopy of the shrubs expands, grass and forb production will be reduced.

Figure 17. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 9. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 600 | 1200 | 1800 |

| Shrub/Vine | 500 | 600 | 700 |

| Forb | 80 | 120 | 170 |

| Tree | 20 | 30 | 30 |

| Total | 1200 | 1950 | 2700 |

Figure 18. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX4534, Converted Land - Woody Seedlings Encroachment. Woody seedling encroachment on converted lands such as abandoned cropland, native seeded land, and introduced seeding lands..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 18 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

Pathway 3.2A

Community 3.2 to 3.1

In order to transition back to Converted Land Community (3.2), control of the brush species is required. Options include mechanical control or chemical brush removal.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

If heavy continuous grazing occurs, the plant community will transition to the Chaparral Shrubland State (2) with a woody canopy greater than 30 percent. When this occurs, a threshold has been crossed.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The Chaparal Grassland State (1) can be changed into the Converted Land State (3) by controlling the brush and seeding to native or introduced grasses. Due to the gravelly soils of this site, care should be taken in the selection of soil disturbance equipment. Removing the brush and reseeding represents the crossing of a threshold.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Full restoration back to the Chaparral Grassland is difficult and requires high energy inputs. Mechanical or chemical brush control is required to remove the woody species that have invaded the site. Range seeding may be necessary if the seed bank has been severely reduced.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

The Shrubland Community (2.1) can be changed into the Converted Land State (3) by controlling the brush and seeding to native or introduced grasses. Due to the gravelly soils of this site, care should be taken in the selection of soil disturbance equipment. Removing the brush and reseeding represents the crossing of a threshold.

Additional community tables

Table 10. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Midgrasses | 560–1200 | ||||

| plains bristlegrass | SEVU2 | Setaria vulpiseta | 100–400 | – | ||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 100–400 | – | ||

| beardgrass | BOTHR | Bothriochloa | 100–400 | – | ||

| Arizona cottontop | DICA8 | Digitaria californica | 100–400 | – | ||

| Texas bristlegrass | SETE6 | Setaria texana | 100–200 | – | ||

| 2 | Midgrasses | 140–300 | ||||

| slender grama | BORE2 | Bouteloua repens | 100–200 | – | ||

| green sprangletop | LEDU | Leptochloa dubia | 100–200 | – | ||

| lovegrass tridens | TRER | Tridens eragrostoides | 100–200 | – | ||

| 3 | Shortgrasses | 210–450 | ||||

| hooded windmill grass | CHCU2 | Chloris cucullata | 100–200 | – | ||

| fall witchgrass | DICO6 | Digitaria cognata | 100–200 | – | ||

| Hall's panicgrass | PAHA | Panicum hallii | 100–200 | – | ||

| 4 | Shortgrasses | 70–150 | ||||

| threeawn | ARIST | Aristida | 50–90 | – | ||

| slim tridens | TRMU | Tridens muticus | 50–90 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 5 | Forbs | 70–150 | ||||

| prairie clover | DALEA | Dalea | 50–100 | – | ||

| awnless bushsunflower | SICA7 | Simsia calva | 50–100 | – | ||

| beeblossom | GAURA | Gaura | 25–75 | – | ||

| snoutbean | RHYNC2 | Rhynchosia | 25–75 | – | ||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 25–75 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 6 | Shrubs | 280–600 | ||||

| guajillo | ACBE | Acacia berlandieri | 200–500 | – | ||

| blackbrush acacia | ACRI | Acacia rigidula | 200–500 | – | ||

| 7 | Shrubs | 70–150 | ||||

| mouse's eye | BEMY | Bernardia myricifolia | 50–100 | – | ||

| spiny hackberry | CEEH | Celtis ehrenbergiana | 50–100 | – | ||

| Texas lignum-vitae | GUAN | Guaiacum angustifolium | 50–100 | – | ||

| pricklypear | OPUNT | Opuntia | 50–100 | – | ||

| live oak | QUVI | Quercus virginiana | 50–100 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

As a historic tall/midgrass prairie, this site was occupied by bison, antelope, deer, quail, turkey, and dove. This site was also used by many species of grassland songbirds, migratory waterfowl, and coyotes. This site now provides forage for livestock and is still used by quail, dove, migratory waterfowl, grassland birds, coyotes, and deer.

Feral hogs (Sus scrofa) can be found on most ecological sites in Texas. Damage caused by feral hogs each year includes, crop damage by rutting up crops, destroyed fences, livestock watering areas, and predation on native wildlife, and ground-nesting birds. Feral hogs have few natural predators, thus allowing their population to grow to high numbers.

Wildlife habitat is a complex of many different plant communities and ecological sites across the landscape. Most animals use the landscape differently to find food, shelter, protection, and mates. Working on a conservation plan for the whole property, with a local professional, will help managers make the decisions that allow them to realize their goals for wildlife and livestock.

Grassland State (1): This state provides the maximum amount of forage for livestock such as cattle. It is also utilized by deer, quail and other birds as a source of food. When a site is in the reference plant community phase (1.1) it will also be used by some birds for nesting, if other habitat requirements like thermal and escape cover are near.

Tree/Shrubland (2): This state can be maintained to meet the habitat requirements of cattle and wildlife. Land managers can find a balance that meets their goals and allows them flexibility to manage for livestock and wildlife. Forbs for deer and birds like quail will be more plentiful in this state. There will also be more trees and shrubs to provide thermal and escape cover for birds as well as cover for deer.

Converted Land State (3): The quality of wildlife habitat this site will produce is extremely variable and is influenced greatly by the timing of rain events. This state is often manipulated to meet landowner goals. If livestock production is the main goal, it can be converted to pastureland. It can also be planted to a mix of grasses and forbs that will benefit both livestock and wildlife. A mix of forbs in the pasture could attract pollinators, birds and other types of wildlife. Food plots can also be planted to provide extra nutrition for deer.

This rating system provides general guidance as to animal preference for plant species. It also indicates possible competition between kinds of herbivores for various plants. Grazing preference changes from time to time, especially between seasons, and between animal kinds and classes. Grazing preference does not necessarily reflect the ecological status of the plant within the plant community. For wildlife, plant preferences for food and plant suitability for cover are rated. Refer to habitat guides for a more complete description of a species habitat needs.

Recreational uses

Hunting and photography are common activities.

Wood products

In the Grassland State, no wood products are available. In a Shrubland State, the site may produce many large mesquite trees and these are often cut for firewood and barbecue.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented was derived from the revised Range Site, literature, limited NRCS clipping data (417s), field observations, and personal contacts with range-trained personnel.

Other references

AgriLife. 2009. Managing Feral Hogs Not a One-shot Endeavor. AgNews, April 23, 2009. http://agnews.tamu.edu/showstory.php?id=903.

Baen, J. S. 1997. The growing importance and value implications of recreational hunting leases to agricultural land investors. Journal of Real Estate Research, 14:399-414.

Bestelmeyer, B. T., J.R. Brown, K. M. Havstad, R. Alexander, G. Chavez, and J. E. Herrick. 2003. Development and use of state-and-transition models for rangelands. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):114-126.

Briske, B B, B. T. Bestelmeyer, T. K. Stringham, and P. L. Shaver. 2008. Recommendations for development of resilience-based State-and-Transition Models. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 61:359-367.

Diamond, D. D. and T. E. Fulbright. 1990. Contemporary plant communities of upland grasslands of the Coastal Sand Plain, Texas. Southwestern Naturalist, 35:385-392.

Dillehay T. 1974. Late quaternary bison population changes on the Southern Plains. Plains Anthropologist, 19:180-96.

Foster, J. H. 1917. Pre-settlement fire frequency regions of the United States: a first approximation. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings No. 20.

Frost, C. C. 1995. Presettlement fire regimes in southeastern marshes, peatlands, and swamps. In: Prodeedings, 19th Tall Timbers fire ecology conference, 39-60. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL.

Fulbright, T. E. and S. L. Beasom. 1987. Long-term effects of mechanical treatment on white-tailed deer browse. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 15:560-564.

Hamilton, W. and D. Ueckert. 2005. Rangeland Woody Plant Control: Past, Present, and Future. In: Brush Management: Past, Present, and Future, 3-16. Texas A&M University Press. College Station, TX.

Kneuper, C. L., C. B. Scott, and W. E. Pinchak. 2003. Consumption and dispersion of mesquite seeds by ruminants. Journal of Range Management, 56:255-259.

Lehman, V. W. 1969. Forgotten Legions: Sheep in the Rio Grande Plain of Texas. Texas Western Press, El Paso, TX.

McClendon, T. 1991. Preliminary description of the vegetation of South Texas exclusive of the Coastal Saline Zones. Texas Journal of Science, 43:13-32.

Norwine, J. and R. Bingham. 1986. Frequency and severity of droughts in South Texas: 1900-1983, 1-17. In Livestock and wildlife management during drought. Edited by R. D. Brown. Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Kingsville, TX.

Rhyne, M. Z. 1998. Optimization of wildlife and recreation earnings for private landowners. M. S. Thesis, Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Kingsville, TX.

Scifres C. J., W. T. Hamilton, J. R. Conner, J. M. Inglis, and G. A. Rasmussen. 1985. Integrated Brush Management Systems for South Texas: Development and Implementation. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, College Station, TX.

Scifres, C. J. and W. T. Hamilton. 1993. Prescribed burning for brushland management: the South Texas example. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX.

Smeins, F. E., D. D. Diamond, and W. Hanselka. 1991. Coastal prairie, 269-290. In Ecosystems of the World: Natural Grasslands. Edited by R. T. Coupland. Elsevier Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Snyder, R. A. and C. L. Boss. 2002. Recovery and stability in barrier island plant communities. Journal of Coastal Research, 18:530-536.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 2007. List of White-tailed Deer Browse and Ratings. District 8.

Urbatsch, L. 2000. Chinese tallow tree (Triadica sebifera (L.) Small. USDA-NRCS Plant Guide.

Wright, B. D., R. K. Lyons, J. C. Cathey, and S. Cooper. 2002. White-tailed deer browse preferences for South Texas and the Edwards Plateau. Texas Cooperative Extension Bulletin B-6130.

Wright, H.A. and A.W. Bailey. 1982. Fire Ecology: United States and Southern Canada. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Contributors

Gary Harris, MSSL, NRCS, Robstown, Texas

Approval

Bryan Christensen, 9/21/2023

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 09/23/2023 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time, coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Extensive soil disturbance followed by seeding improved forage species |

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of historic disturbance return intervals. May be require seeding with native species. |

| T2A | - | Extensive soil disturbance followed by seeding improved forage species |