Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R083EY020TX

Sand Hills

Last updated: 9/21/2023

Accessed: 02/27/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

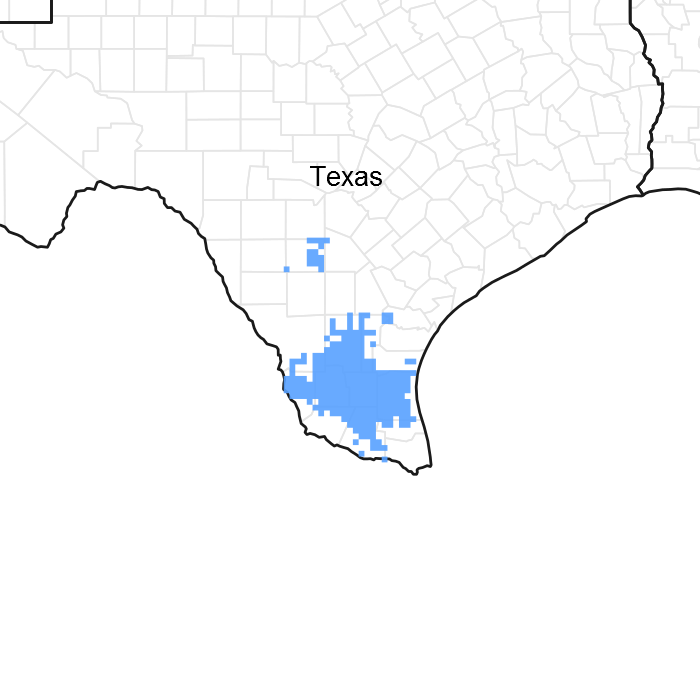

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 083E–Sandsheet Prairie

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 83E makes up about 4,300 square miles (11,150 square kilometers). The towns of Falfurrias, Premont, and Sarita are in this area. U.S. Highways 77 and 281 run through the area in a north-south direction.

Classification relationships

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006.

-Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 83E

Ecological site concept

Sand Hill sites are very deep sands with little horizon development. Active dunes can form without vegetation to hold the soil in place.

Associated sites

| R083EY008TX |

Salty Prairie |

|---|---|

| R083EY021TX |

Sandy |

| R083EY023TX |

Sandy Loam |

| R083EY014TX |

Sandy Flat |

| R083EY022TX |

Loamy Sand |

Similar sites

| R083AY020TX |

Sand Hills |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Quercus virginiana |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Schizachyrium littorale |

Physiographic features

The Sand Hills Ecological Site was formed in very deep sandy eolian deposits on the Sandsheet Prairie of the South Texas Sand Plain. The sands have been worked and reworked by the dominant southeasterly winds. The site is found on nearly level to moderately steep vegetated dunes. Slopes range from 0 to 15 percent. Elevation is 15 to 500 feet.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Sand plain

> Dune

(2) Sand plain > Sand sheet |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to very low |

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 20 – 290 ft |

| Slope | 15% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

MLRA 83 has a subtropical subhumid climate. Winters are dry and fairly warm, and the summers are hot and humid. Tropical maritime air masses predominate throughout spring, summer and fall. Modified polar air masses exert considerable influence during winter, creating a continental climate characterized by large variations in temperature. Peak rainfall occurs late in spring and a secondary peak occurs early in fall. Heavy thunderstorm activities increase in April, May, and June. July is hot and dry with little weather variations. Rainfall increases again in late August and September as tropical disturbances increase and become more frequent. Tropical air masses from the Gulf of Mexico dominate during the spring, summer and fall. Prevailing winds are southerly to southeasterly throughout the year except in December when winds are predominately northerly.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 235-365 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 24-29 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 222-365 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 22-30 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 288 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 26 in |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) KINGSVILLE NAAS [USW00012928], Kingsville, TX

-

(2) FALFURRIAS [USC00413063], Encino, TX

-

(3) MCCOOK [USC00415721], Edinburg, TX

-

(4) RAYMONDVILLE [USC00417458], Raymondville, TX

-

(5) SARITA 7 E [USC00418081], Sarita, TX

-

(6) HEBBRONVILLE [USC00414058], Hebbronville, TX

Influencing water features

Runoff is negligible or very low due to the sandy surface texture. Drainage is somewhat excessive or excessive.

Wetland description

N/A.

Soil features

The soils are very deep, somewhat excessive or excessively drained with rapidly permeability. Surface and subsurface textures are fine sands or sands. The soils are classified as Typic Ustipsamments and have little horizon development. Soil series correlated to this site include: Arenisco, Falfurrias and Medanito.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Eolian sands

–

sedimentary rock

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Fine sand |

| Family particle size |

(1) Sandy |

| Drainage class | Somewhat excessively drained to excessively drained |

| Permeability class | Rapid |

| Soil depth | 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

2 – 3 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

5 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

5.1 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

The plant communities of this site are dynamic and community composition may vary dramatically with variations in annual rainfall, grazing, and fire. During dry periods the amount of bare ground increases. Bare ground may predominate during droughts. Shortgrasses such as hairy grama (Bouteloua hirsuta), thin paspalum (Paspalum setaceum), fringed signalgrass (Brachiaria ciliatissima), red lovegrass (Eragrostis secundiflora), sandbur (Cenchrus spp.), and forbs increase in abundance at the expense of the taller grasses. During wet years, tallgrasses such as seacoast bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium var. littorale) increase in abundance. The shortgrasses and forbs form a multi-layered community.

In 1834, Jean Luis Berlandier referred to the region as a “wilderness of plains covered with small forests of oaks.” Berlandier remarked that it was grazed by cattle (Bos spp.) and large herds of wild horses (Equas caballus). In the 1840’s and 1850’s, parts of Nueces, Kleberg, Brooks and Kenedy Counties were known as the “Wild Horse Desert.” Wild horses were reported in other portions of the Rio Grande Plains as early as 1821. Bartlett in 1853 noted in Kleberg county thousands of wild horses fleeing a prairie fire.

Property lines of Spanish and Mexican land grants were often laid out from one live oak (Quercus virginiana) motte to another. Some of the live oaks are more than 300 years old. Scattered mesquites (Prosopis glandulosa) also occur, the oldest presently about 250 years old. Historically, fire was an important factor. Wildfires are common on this site at present, and Native Americans set periodic fires for hunting and reducing insects. Natural fires, and fires set by Native Americans, reduced woody plant cover, kept live oak mottes scattered and isolated, and maintained the open stretches of grassland witnessed by Berlandier. White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and pronghorns (Antilocapra americana) were the major large herbivores on this site at the time of colonization by Europeans. In 1846 McClintock reported “thin bushes on the sands of Kleberg County at wide intervals and thousands of deer.” The extent to which bison (Bos bison) utilized the site is unknown.

The reference plant community is a grassland with scattered live oak mottes and occasional mesquite trees. Seacoast bluestem is the prevailing dominant. Gulfdune paspalum (Paspalum monostachyum) is a co-dominant with seacoast bluestem on moderately drained flats and swales. Gulfdune paspalum declines dramatically in abundance in the drier microhabitats of well-drained flats and ridges where seacoast bluestem becomes the primary dominant. Gulfdune paspalum also declines in abundance with declining annual rainfall away from the coast. Pan-American balsamscale (Elyonurus tripsacoides) becomes a co dominant with seacoast bluestem in areas more than 25 to 30 miles from the coast. Other important associated grasses include big bluestem, brownseed paspalum (Paspalum plicatulum), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum spp.), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and thin paspalum. The reference community supports a diverse understory of perennial legumes and forbs.

Continued overuse by livestock results in a decline of seacoast bluestem, gulfdune paspalum, and other perennial grasses. This causes an increase in forbs, particularly camphor daisy (Rayjacksonia phyllocephala), partridgepea (Chamaecrista fasciculate), and crotons (Croton spp.). Camphor daisy has increased in recent history and now dominates this site, forming 10 to 20 percent of the canopy cover, even under good to excellent range conditions. Camphor daisy was apparently absent from the site as recently as 1963. Pan-American balsamscale, three-awns (Aristida spp.), and thin paspalum increase in abundance with heavy grazing, but decline on severely grazed rangeland. On severely grazed rangeland, seacoast bluestem is virtually absent. Sandbur, fringed signalgrass, red lovegrass, camphor daisy, and other forbs dominate severely grazed sites. Overuse results in a large amount of bare ground, which results in blowing sand. Blowing sand further accelerates community degradation. Live oak mottes expand and coalesce forming continuous oak forests with continued overuse. The oak colonies often become short and thicketized with high stem density, rather than forming large, single-trunked trees. Mesquite increases with continued overuse. Once the mesquites reach sufficient size, understory shrubs including granjeno (Celtis pallida), brasil (Condalia hookeri), and lime prickly-ash (Zanthoxylum fagara) establish underneath.

Active sand dunes occur on this site. Overuse by livestock exacerbates dune formation. Continuous dunes sometimes cover several square miles. The dunes add to landscape diversity, but pose management problems because they migrate across the landscape and may cover fences, roads, buildings, and other structures. Cutting, mulching, and lightly incorporating native hay near a sand dune is an effective method of stabilizing dunes.

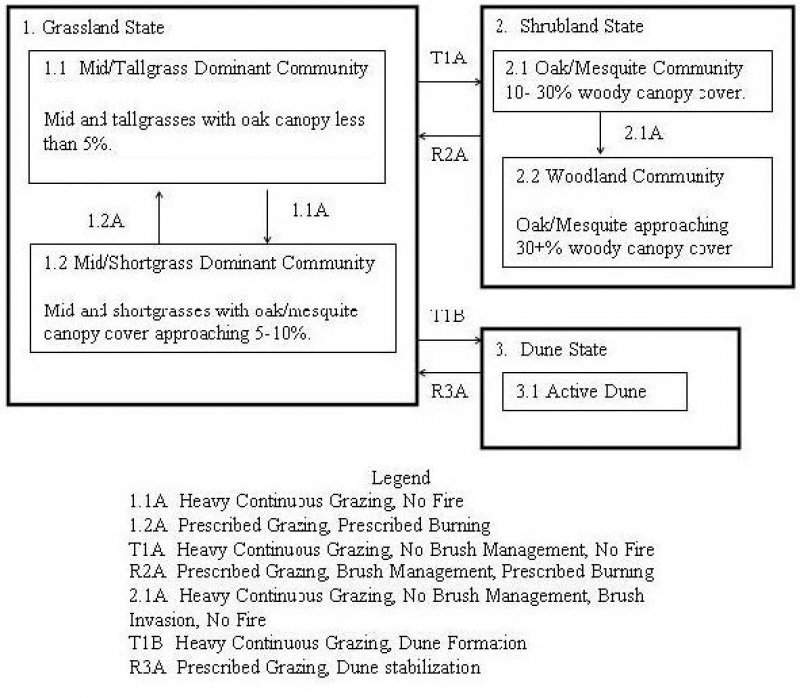

State and transition model

Figure 8. STM

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Grassland

Community 1.1

Mid/Tallgrass Dominant

The reference plant community for the site is open grassland composed of mid and tallgrasses with scattered live oaks. Live oaks shades less than five percent of the site. Seacoast bluestem and gulfdune paspalum dominate the site, with gulfdune paspalum giving way to Pan American balsamscale as distance increases from the coast. Pan American balsamscale, thin paspalum, and arrow feather threeawn dominant drier sites away from the coast. Recurrent fire was a natural process that maintained the plant community. A prescribed burning program with fire every two to three years and proper grazing management are required to maintain the open grassland community.

Figure 9. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 850 | 1750 | 2600 |

| Forb | 100 | 150 | 250 |

| Shrub/Vine | 50 | 100 | 150 |

| Tree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1000 | 2000 | 3000 |

Figure 10. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX8513, Mid/Tallgrass Community. Mid and tallgrasses dominate the site with few forbs and shrubs..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

Community 1.2

Mid/Shortgrass Dominant

Heavy grazing creates opportunity for a change in plant community composition from an open grassland with scattered live oaks to a mid and shortgrass community. Drought hastens the process. This community is dominated by Pan American balsamscale and shortgrasses including arrow feather threeawn, sandbur, fringed signalgrass, red lovegrass; camphor daisy, partridge pea, and crotons. Seacoast bluestem is present, but is greatly reduced in cover compared to the 1.1 Mid/Tallgrass Dominant Community. Bare ground increases under heavy grazing. Live oak and mesquite are more prominent in this community. As long as there is enough grass to burn, this community can be maintained with periodic fires and some selective brush management. However, as mesquite and oak approach 10 to 30 percent canopy, a threshold is reached, and prescribed grazing alone will not control the brush.

Figure 11. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 790 | 1600 | 2350 |

| Forb | 100 | 150 | 300 |

| Tree | 60 | 120 | 200 |

| Shrub/Vine | 50 | 100 | 150 |

| Total | 1000 | 1970 | 3000 |

Figure 12. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX8514, Mid/Shortgrass Parkland Community. Mid and shortgrasses dominate while oak mottes and density of mesquite are expanded..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Heavy continuous graving and lack of fire cause the site to transition the 1.2 Mid/Shortgrass Dominant Community.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Prescribed grazing and re-introduction of fire will transition the community back to the 1.1 Mid/Tallgrass Dominant Community.

State 2

Shrubland

Community 2.1

Oak/Mesquite

Heavy grazing and lack of fire caused the transition from the Grassland State to a state in which oaks and mesquite dominate. Arrow feather threeawn, sandbur, fringed signalgrass, red lovegrass; and forbs are the dominant herbaceous plants. Seacoast bluestem and Pan American balsamscale occur only in scattered patches. Considerable bare ground is present. Brush management will be necessary to recover to the Grassland State (1). Any investment in brush management should be done with skill due to the fragile nature of the dunes. Proper grazing management helps to extend the life of the practice. The prudent use of fire can be used to arrest brush encroachment. Without brush management, this 10 to 30 percent cover will develop into the 2.2 Woodland Community.

Figure 13. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 440 | 1000 | 1600 |

| Shrub/Vine | 130 | 315 | 500 |

| Tree | 130 | 315 | 500 |

| Forb | 100 | 250 | 400 |

| Total | 800 | 1880 | 3000 |

Figure 14. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX8506, Shrubland Community, 10-30% canopy. Expansion and coalescence of live oak mottes, and establishment of mesquite and associated woody species while grass species decline..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 18 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

Community 2.2

Woodland

As lack of brush management, heavy grazing, and absence of fire continues, live oak mottes may expand and coalesce resulting in greater than 30 percent woody canopy cover. Much of the live oak may be a low-growing thicket. Likewise, mesquite may increase with an understory of subordinate shrubs such as granjeno, brasil, and lime pricklyash. Seacoast bluestem and other midgrasses are virtually absent. Arrow feather threeawn, sandbur, fringed signalgrass, red lovegrass, and forbs are the dominant herbaceous plants.

Figure 15. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 300 | 700 | 1100 |

| Tree | 240 | 600 | 900 |

| Shrub/Vine | 160 | 380 | 600 |

| Forb | 100 | 250 | 400 |

| Total | 800 | 1930 | 3000 |

Figure 16. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX8507, Woodland Community, 30+% canopy. Woody canopy is greater than 30%..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 18 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Continued heavy grazing, no fire, and no brush management will transition the site to the 2.2 Woodland Community.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Brush management is required to reduce the woody canopy less than 30 percent. Care is required because the sandy soils have a tendency to form dunes.

State 3

Dune

Community 3.1

Active Dune

Continued heavy grazing of the Grassland State results in the formation of active sand dunes. Severe climate events, such as hurricanes, can also trigger dune formation. Vegetation is absent from the dune itself. Active dunes migrate with the prevailing wind from southeast to northwest. Stabilized dunes undergo a successional progression with snake cotton (Froelichia spp.), sunflowers (Helianthus spp.), and croton. Once stabilization has been achieved, heavy grazing will erase any gains and precipitate reformation of an active dune. Rest and implementation of proper grazing management are required to allow plants to establish and stabilize active dunes, but the process may take several years. Cutting, mulching, and lightly incorporating native hay near a sand dune is an effective method of stabilizing dunes.

Figure 17. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 9. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tree | 330 | 550 | 750 |

| Forb | 80 | 150 | 250 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 80 | 150 | 250 |

| Shrub/Vine | 80 | 150 | 250 |

| Total | 570 | 1000 | 1500 |

Figure 18. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX8516, Active Dune Community. Dunes are active and migrate with the wind. Vegetation are absent from the active dunes. Surrounding areas will have low successional grasses and forbs..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

With continued heavy grazing and no fire, the site will transition to the Shrubland State. The shrubs and brush exceed a 10 percent canopy cover and the herbaceous understory is greatly reduced.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

If the site is grazed heavy enough without rest, the site can transition the Dune State. Without herbaceous cover, bare ground increases and active dunes can form, moving across the landscape.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Brush management, prescribed grazing, and the return of fire can restore the plant community to the Grassland State. Care should be taken to minimally disturb the soils, due to their ability to form active dunes.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 1

Stabilization of dunes is required to restore the Grassland State. Stabilization can occur naturally by first colonization of first successional herbaceous species or active restoration by cutting, mulching, and lightly incorporating native hay.

Additional community tables

Table 10. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Tallgrasses | 750–1600 | ||||

| shore little bluestem | SCLI11 | Schizachyrium littorale | 500–1500 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 100–1000 | – | ||

| gulfdune paspalum | PAMO4 | Paspalum monostachyum | 500 | – | ||

| 2 | Tallgrasses | 0–300 | ||||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 0–300 | – | ||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 0–300 | – | ||

| 3 | Midgrasses | 100–300 | ||||

| tanglehead | HECO10 | Heteropogon contortus | 100–250 | – | ||

| brownseed paspalum | PAPL3 | Paspalum plicatulum | 100–250 | – | ||

| crinkleawn grass | TRACH2 | Trachypogon | 100–250 | – | ||

| 4 | Midgrasses | 200–400 | ||||

| crabgrass | DIGIT2 | Digitaria | 100–200 | – | ||

| balsamscale grass | ELION | Elionurus | 100–200 | – | ||

| knotgrass | PADI6 | Paspalum distichum | 100–200 | – | ||

| thin paspalum | PASE5 | Paspalum setaceum | 100–200 | – | ||

| Wright's threeawn | ARPUW | Aristida purpurea var. wrightii | 50–100 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 5 | Forbs | 25–100 | ||||

| bundleflower | DESMA | Desmanthus | 25–75 | – | ||

| coastal indigo | INMI | Indigofera miniata | 25–75 | – | ||

| dotted blazing star | LIPU | Liatris punctata | 25–75 | – | ||

| sensitive plant | MIMOS | Mimosa | 25–75 | – | ||

| yellow puff | NELU2 | Neptunia lutea | 25–75 | – | ||

| American snoutbean | RHAM | Rhynchosia americana | 25–75 | – | ||

| 6 | Forbs | 0–50 | ||||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 0–50 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 7 | Shrubs | 75–125 | ||||

| live oak | QUVI | Quercus virginiana | 75–200 | – | ||

| 8 | Shrubs | 0–25 | ||||

| spiny hackberry | CEEH | Celtis ehrenbergiana | 0–1 | – | ||

| snakewood | CONDA | Condalia | 0–1 | – | ||

| pricklypear | OPUNT | Opuntia | 0–1 | – | ||

| mesquite | PROSO | Prosopis | 0–1 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Cattle (Bos spp.) and many species of wildlife make extensive use of this ecological site. White-tailed deer may be found scattered across the prairie, and are found in heavier concentrations where woody cover exists. Feral hogs (Sus scrofa) are present and, at times, become abundant. Coyotes (Canis latrans) are abundant, and probably have replaced the red wolf (Canis rufus) in this mammalian predator niche. Rodent populations rise during drier periods and fall during periods of inundation. Geese (family Anatidae) and sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis) abound during winter. Many species of avian predators including northern harriers (Circus cyaneus), red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), kestrels (Falco sparverius), white-tailed kites (Elanus leucurus), and, occasionally, swallow-tailed kites (Elanoides forficatus). Many species of grassland birds use the ecological site, including blue grosbeaks (Guiraca caerulea), dickcissels (Spiza americana), eastern meadowlarks (Sturnella magna), and several sparrows, including Cassin’s sparrow (Aimophila cassinii), vesper sparrow (Pooecetes gramineus), lark sparrow (Chondestes grammacus), savannah sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis), grasshopper sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum), and Le Conte’s sparrow (Ammodramus leconteii).

Hydrological functions

Water infiltration is rapid in the fine sands of the site. Therefore, runoff and soil erosion from water is seldom a problem on the site.

Recreational uses

Ecotourism and hunting are popular activities.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

The data in this document was obtained by reviewed historical accounts, research reports, limited clipping data, and from the experience of range trained field personnel.

Other references

Archer, S. 1995. Tree-grass dynamics in a Prosopis-thornscrub savanna parkland: reconstructing the past and predicting the future. Ecoscience, 2:83-99.

Archer, S. 1990. Development and stability of grass/woody mosaics in a subtropical savanna parkland, Texas, USA. Journal of Biogeography 17: 453-462.

Archer, S., C. Scifres, C. R. Bassham, and R. Maggio. 1988. Autogenic succession in a subtropical savanna: conversion of grassland to thorn woodland. Ecological Monographs 58(2):110-127.

Baen, J. S. 1997. The growing importance and value implications of recreational hunting leases to agricultural land investors. Journal of Real Estate Research, 14:399-414.

Beasom, S. L, G. Proudfoot, and J. Mays. 1994. Characteristics of a live oak-dominated area on the eastern South Texas Sand Plain. In the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute Annual Report, 1-2.

Berlandier, J. L. 1980. Journey to Mexico during the years 1826 to 1834: translated. Texas State Historical Associated and the University of Texas. Austin, TX.

Bond, W. J. What Limits Trees in C4 Grasslands and Savannas? Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 39:641-659.

Diamond, D. D. and T. E. Fulbright. 1990. Contemporary plant communities of upland grasslands of the Coastal Sand Plain, Texas. Southwestern Naturalist, 35:385-392.

Ford, J. S. 2010. Rip Ford’s Texas. University of Texas Press. Austin, TX.

Fulbright, T. E. and F. C. Bryant. 2003. The Wild Horse Desert: climate and ecology. The Ranch Management, 35-58.

Fulbright, T. E., D. D. Diamond, J. Rappole, and J. Norwine. 1990. The Coastal Sand Plain of Southern Texas. Rangelands, 12:337-340.

Hanselka, C. W., D. L. Drawe, and D. C. Ruthven, III. 2004. Management of South Texas Shrublands with prescribed fire. In Proceedings: Shrubland dynamics -- fire and water, 57-61.

Inglis, J. M. 1964. A history of vegetation of the Rio Grande Plains. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Bulletin No. 45, Austin, TX.

Johnson, M. C. 1963. Past and present grasslands of southern Texas and northeastern Mexico. Ecology 44(3):456-466.

Jurena, P.N., and S. Archer. 2003. Woody Plant Establishment and Spatial Heterogeneity in Grasslands Ecology, 84(4):907-919.

Lehman, V. W. 1969. Forgotten legions: sheep in the Rio Grande Plains of Texas. Texas Western Press, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX.

McLendon T. 1991. Preliminary description of the vegetation of South Texas exclusive of coastal saline zones. Texas Journal of Science, 43: 13-32

Neilson, R. P. 1987. Biotic regionalization and climatic controls in western North America. Vegetatio, 70(3): 135-147.

Norwine, J. and R. Bingham. 1986. Frequency and severity of droughts in South Texas: 1900-1983, 1-17. In Livestock and wildlife management during drought. Edited by R. D. Brown. Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Kingsville, TX.

Palmer, G. R., T. E. Fulbright, and G. McBryde. 1995. Inland sand dune reclamation on the Coastal Sand Plain of Southern Texas. in the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute Annual Report, 30-31.

Rappole, J. H. and G. W. Blacklock. 1994. A field guide: Birds of Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Rhyne, M. Z. 1998. Optimization of wildlife and recreation earnings for private landowners. M. S. Thesis, Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Kingsville, TX.

Woodin, M. C., M. K. Skoruppa, and G. C. Hickman. 2000. Surveys of night birds along the Rio Grande in Webb County, Texas. In Final Report, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Corpus Christi, Texas.

Contributors

Gary Harris, MSSL, NRCS, Robstown, Texas

Approval

Bryan Christensen, 9/21/2023

Acknowledgments

Reviewers and Technical Contributors:

Jason Hohlt, RMS, NRCS, Kingsville, Texas

Vivian Garcia, RMS, NRCS, Corpus Christi, Texas

Shanna Dunn, RSS, NRCS, Corpus Christi, Texas

Mark Moseley, RMS, NRCS, Boerne, Texas

Justin Clary, RMS, NRCS, Temple, Texas

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Vivian Garcia, Zone RMS, NRCS, Corpus Christi, Texas |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | 361-241-0609 |

| Date | 01/12/2010 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

None. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

None. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

0 to 5 percent bare ground. Small and non-connected areas. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

None. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

Due to the sandy properties of the soil, severe soil erosion by wind can occur. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Under normal rainfall, little litter movement should be expected; however, litter of all sizes may move long distances. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil surface under the reference community is resistant to erosion. Stability class range is expected to be 5 to 6. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

0 to 3 inches, very pale brown (10YR 7/3) fine sand, brown (10YR 5/3) moist; single grain; loose; common fine roots; slightly acid; clear smooth boundary. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

High canopy, basal cover and density with small interspaces should make rainfall impact negligible. This site has well drained soils, deep with level to gently sloping (0 to 5 percent) which produces negligible runoff and water erosion. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

No evidence of compaction. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm-season tallgrasses >Sub-dominant:

Warm-season midgrasses >Other:

Forbs > ShrubsAdditional:

Forbs make up 5 percent species composition while shrubs make up 5 percent. -

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Perennial grasses will naturally exhibit a minor amount (less than 5%) of senescence and some mortality every year. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Litter is primarily herbaceous. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

2,500 to 3,500 pounds per acre. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Mesquite and bur grass are the primary invaders. Other invaders include guineagrass, King Ranch bluestem, lotebush, pricklypear, yucca, spiny hackberry, brasil, and live oak. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All perennial species should be capable of reproducing every year unless disrupted by extended drought, overgrazing, wildfire, insect damage, or other events occuring immediately prior to, or during the reproductive phase.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.