Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R085AY379TX

Loamy Slope 30-38

Last updated: 9/21/2023

Accessed: 03/13/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 085A–Grand Prairie

The Grand Prairie MLRA is characterized by predominately loam and clay loam soils underlain by limestone and shale. Topography transitions from steeper ridges and summits of the Lampasas Cut Plain on the southern end to the more rolling hills of the Fort Worth Prairie to the north. The Arbuckle Mountain area in Oklahoma is also within this MLRA.

Classification relationships

This ecological site is correlated to soil components at the Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) level which is further described in USDA Ag Handbook 296.

Ecological site concept

These sites occur on moderately deep and deep, slightly calcareous clay loams soils over limestone. The reference vegetation consists of native tallgrasses with scattered forbs and few woody species. In the absence of fire or other brush management, woody species may increase and dominate the site. Many of these sites have been farmed up for crop production. Some have been planted back to introduced species. * This site was formerly correlated to the Clay Loam ecosite. During the provisional ESD project of 2018 it was identified that the soils associated with the clay loam ecosite warranted additional investigations as there was multiple differences(soil texture, landscape position, production potential, etc.). In order to prioritize these sites for future data collection projects, they were separated into Clayey Slope, Clayey Swale, Loamy Slope and Loamy Swale. The production and plant composition details of this report may be altered pending future investigations.

Associated sites

| R085AY185TX |

Shallow 30-38" PZ Located upslope from the clay loam site and contributes runoff to the clay loam site. |

|---|

Similar sites

| R085AY185TX |

Shallow 30-38" PZ The shallow site yields similar vegetation but with a low yield due to a more shallow soil than the clay loam. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Quercus fusiformis |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Andropogon gerardii |

Physiographic features

This site occurs on linear to convex side slopes, nose slopes, and crests of hillslopes and on risers of stream terraces in the Grand Prairie. This site is characteristically a water distributing site. Slopes typically range from 33 to 12 percent.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hills

> Ridge

(2) Alluvial plain > Stream terrace (3) Hills > Hillslope |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Low to medium |

| Elevation | 152 – 579 m |

| Slope | 3 – 12% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate is subhumid subtropical and is characterized by hot summers and relatively mild winters. Tropical maritime air controls the climate during spring, summer and fall. In winter and early spring, frequent surges of Polar Canadian air cause sudden drops in temperatures and add considerable variety to the daily weather. The average first frost should occur around November 5 and the last freeze of the season should occur around March 19.

The average relative humidity in mid-afternoon is about 60 percent. Humidity is higher at night, and the average at dawn is about 80 percent. The sun shines 75 percent of the time possible during the summer and 50 percent in winter. The prevailing wind direction is from the south and highest windspeeds occur during the spring months.

Approximately two-thirds of annual rainfall occurs during the April to September period. Rainfall during this period generally falls during thunderstorms, and fairly large amounts of rain may fall in a short time. The driest months are usually July and August.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 194-208 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 216-243 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 813-965 mm |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 190-209 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 209-245 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 787-991 mm |

| Frost-free period (average) | 201 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 230 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 889 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BENBROOK DAM [USC00410691], Fort Worth, TX

-

(2) CLEBURNE [USC00411800], Cleburne, TX

-

(3) WHITNEY DAM [USC00419715], Clifton, TX

-

(4) DENTON MUNI AP [USW00003991], Ponder, TX

-

(5) DECATUR [USC00412334], Decatur, TX

-

(6) EVANT 1SSW [USC00413005], Evant, TX

-

(7) BROWNWOOD 2ENE [USC00411138], Early, TX

-

(8) LAMPASAS [USC00415018], Lampasas, TX

Influencing water features

These sites receive some run off from adjacent sites upslope and shed some water to lowland sites. The presence of deep rooted tallgrasses helps to facilitate infiltration of rainwater into the soil profile. These sites are not associated with wetlands.

Wetland description

NA

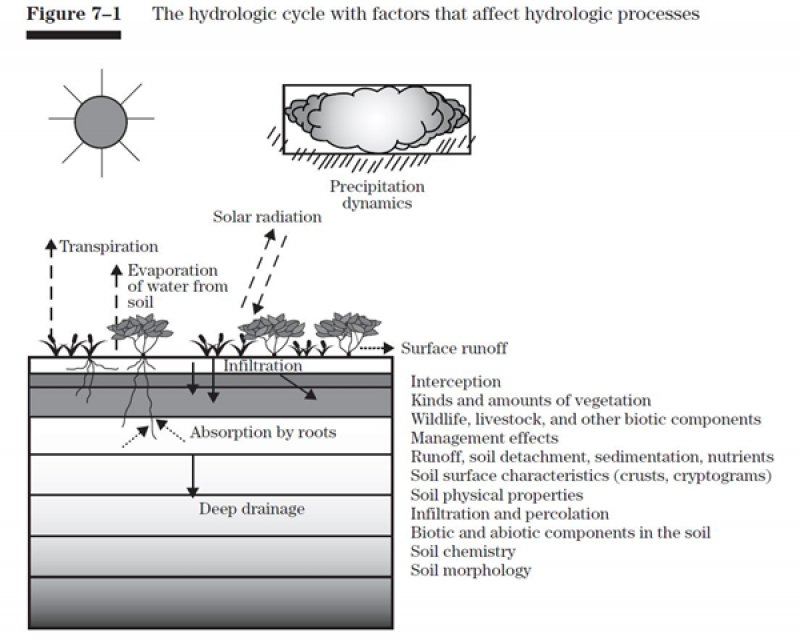

Figure 8.

Soil features

Representative soil components for this ecological site include: Bolar, Lewisville, Nuff, Seawillow, Sunev, Venus, and Topsey

The site is characterized by moderately deep to very deep, loamy, well drained, moderately permeable soils that formed in ancient loamy and clayey calcareous sediments.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

limestone

(2) Alluvium – mudstone (3) Residuum – mudstone (4) Alluvium – limestone |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Clay loam (2) Loam (3) Gravelly loam (4) Gravelly clay loam (5) Stony clay loam (6) Silty clay loam |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow to moderate |

| Soil depth | 51 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 30% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0 – 10% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

10.16 – 27.94 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

10 – 60% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 2 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

7.9 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 25% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 12% |

Ecological dynamics

The reference plant community for the Loamy Slope site is a tallgrass prairie plant community. The grasses are primarily little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) and eastern gamagrass (Tripsacum dactyloides). Little bluestem, big bluestem, and Indiangrass are the most commonly occurring grass species for this site. Smaller amounts of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula) occur as well. Very few shrubs and trees were present in the reference community. The woody component consisted of live oak (Quercus fusiformis), Texas red oak (Quercus buckleyi), elm species (Ulmus spp.), plum species (Prunus spp.), hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) and bumelia (Sideroxylon lanuginosum). Most woody plants tended to be more confined to areas along drainages, areas where soil is somewhat deeper, and along the cedar breaks, which are found along the edges of the Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 85.

To a large extent, the way the site changes depend on the location related to the distance from the West Cross Timbers MLRA 84C. Generally, sites located within a short distance from the MLRA 84C tend to change in the absence of fire toward a mesquite/juniper brushland community while sites located some distance away from the resource area will shift toward a pricklypear cactus / shrubland community. Woody plants have increased over the past 100 to 150 years on virtually all of the sites located nearest to the West Cross Timbers. Where there is a seed source close by, Ashe juniper (Juniperus ashei), Eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) and mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) will readily invade the site. The juniper first occurs under fences, trees and other places where songbirds tend to rest. Fences have aided in the spread of juniper. Mesquite seedpods are relished by livestock and the seed passes through the digestive tract intact and may be moved considerable distance. This places the pods in an ideal medium for germination and establishment when moisture conditions are right. Mesquite tends to be more of an invader species than juniper on this site. Pre-European settlement grazers included bison and deer. The tall and midgrasses are palatable and nutritious and the site can provide year round grazing. The most limiting soil factor for production is soil depth. During very dry periods, the soils can appear rather droughty. When good rainfall is received, the site produces tremendous annual forage production.

Fire has played a major role in the ecology of the site as is true for most of the grasslands. The main effect of fire on this site was to hold woody shrubs and cactus in check. In the absence of fire, brush can invade regardless of the grazing management.

Climate and soils are the most important and limiting factors affecting grass vegetation on the site. Fires of pre-settlement days were probably more severe due to more fuel being available which could have been more damaging to woody plants. Fire usually creates more diversity in this site for a year or two post-burn. Forbs also need spring moisture which is perhaps the major factor in creating diversity in the plant community. Prescribed fire is sometimes used as a tool to promote diversity, mainly for wildlife. Fire will usually not produce much mortality in older woody plants. After brush has been controlled with herbicides or mechanically, fire can be used effectively to suppress regrowth. Small juniper can be killed by fire. Fuel loads are often the most limiting factor for the effective use of prescribed fire on this site. In general, the use of fire on mature (larger) or dense stands of woody plants does not result in the same positive effects that burning has in tallgrass prairie communities. Woody plant suppression using safe approved herbicides is generally more practical, although prescribed fire has a place.

With abusive grazing practices, the vigorous Indiangrass, eastern gamagrass and big bluestem will become lower in vigor while little bluestem will increase then secondary successional species such as silver bluestem (Bothriochloa laguroides) will begin to increase along with an increase of woody plants. Eastern gamagrass is the first species to disappear. Little bluestem is tolerant of some fairly heavy grazing for long periods, but at some point, a threshold is crossed and the ground cover is opened up resulting in bare places where weedy species can establish. Western ragweed (Ambrosia psilostachya), crotons (Croton setigerus), and cool-season annuals will quickly invade if the principal species are in a weakened condition. The seed of many woody species is consumed by birds and when passed through the digestive system and excreted in the manure, the seed find an excellent seedbed complete with moisture and nutrients. Grazing management with cattle alone probably has minimal effect on the proliferation of woody plants, but a good cover of perennial grasses likely minimizes the seed to soil contact the mesquite needs to establish. Grazing plays a major role in brush encroachment by removing grass that could be used as fuel to burn. Prescribed fire provides a good method to control the spread of woody plants. Selective individual plant removal of mesquite and/or juniper is easy and economical when a few plants begin to show up on the site. When the increase of number of plants occurs fairly rapidly, the number of woody plants per acre will soon become too numerous for a successful and feasible individual plant control. Prescribed grazing, applied with a reasonable stocking rate, can sustain the grass species composition and annual forage production near reference community levels. The site can be abused to the point that the perennial warm-season grasses thin out and the lower successional grasses along with annual forbs begin to dominate. This process of degradation usually takes many years and is further exacerbated by summer drought and above average winter moisture.

Long-term droughts that occur only three to four times in a century can effect some change in plant communities, when coupled with abusive grazing. Short-term droughts are common and usually do not have a lasting effect in changing stable plant communities, although annual production will be affected. The effects of seasonal moisture and short-term dry spells may become more pronounced after the site crosses thresholds to other vegetative states. Plant communities that consist of warm-season perennial grasses, such as little bluestem and associated species of the reference community, are able to persist and withstand climatic extremes with only minor shifts in the overall plant community. When a brush canopy becomes established which shades the ground sufficiently, cool-season annual species tends to be favored. Once a state of brush and cool-season annuals is reached, recovery to a good perennial warm-season grass cover is unlikely without major input with brush management and reseeding.

In summary, the change in states of vegetation depend on the type of grazing management, prescribed fire, and brush management applied over many years, and the rate of invasion and establishment of woody species.

This site historically, was inhabited by grassland wildlife species such as bison, grassland birds and small mammals. Deer and turkey were mostly found along the wooded streams adjacent to this site, occasionally feeding on the open prairie. Large predators such as wolves, coyotes, mountain lions and black bear roamed throughout the area. Over the years, as the site has changed to a more mixed grass and shrub community, more wildlife species have come to utilize it for habitat. Woody plants provide cover for white-tailed deer and bob white quail. These wildlife species have both increased along with the brushy plants due to the cover that these plants provide. More forbs are needed to meet these species food requirements. Woody plants for browse and mast are important for deer. It should be noted that managing for some vegetative communities may meet some wildlife species requirements but will not be as productive for livestock grazing purposes. Also, these communities may not satisfy important ecological functions such as nutrient cycling, hydrologic protection, plant community stability or soil protection.

Hydrologically, the site contributes runoff to the down-slope draws, creeks, and streams that are common in the MLRA. If the perennial grass cover is maintained in good vigor, then maximum infiltration occurs and runoff is reduced. More water entering into the soil profile means a healthier and more productive plant community. Due to the clayey soil underlain with limestone, there is limited deep infiltration. More perennial grass cover means less runoff may result; but the runoff that may occur carries less sediment. Overall, watershed protection and nutrient cycling are enhanced by a healthy grassland community, such as the Tallgrass Prairie Community.

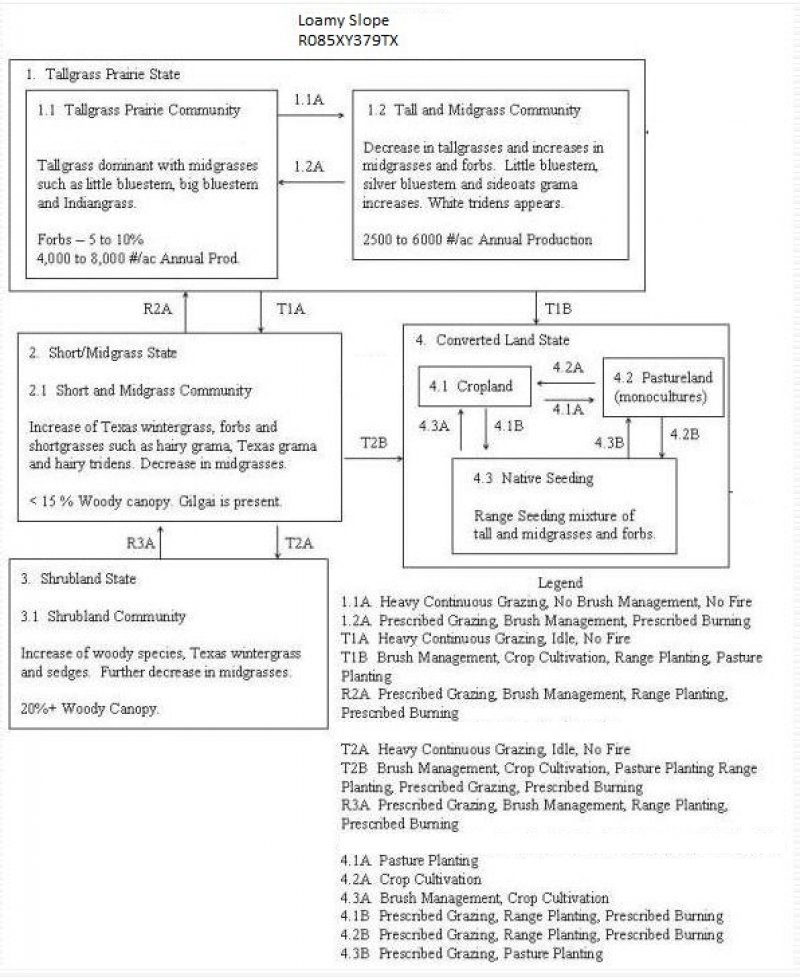

State and Transitional Pathways (S&T): Narrative

The following diagram suggests some pathways that the vegetation on this site might take in response to the various conservation treatments or natural stimuli that may occur over time. There may be other states which may occur that are not shown on this diagram. This S & T Model was developed to show various changes in the plant community that can occur due to management and natural factors. The communities can be manipulated by implementing certain practices. The plant communities described in the S &T Model are commonly observed on this site in the MLRA 85. Before making plans for plant community manipulation for specific purposes, consult local professionals.

As a site changes in plant community makeup, the changes may be due to many factors. Change may occur slowly or in some cases, fairly quickly. As vegetative changes occur, certain thresholds can be crossed. This means that once a certain point is reached during the transition of one community to another, a return to the first state may not be possible without the input of some form of energy. This required input often means intervention with practices that are not part of the natural processes. An example might be the application of herbicide to control some woody species in order to reduce the density and canopy cover and to encourage more grass and forbs growth. Merely adjusting grazing practices would probably not accomplish any significant change in a plant community once certain thresholds are crossed. The amount of energy required to effect change in community would depend on the present vegetative state and the plant community desired by the landowner.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Tallgrass Prairie State - Reference

Dominant plant species

-

Texas live oak (Quercus fusiformis), tree

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), grass

Community 1.1

Tallgrass Prairie Community

Figure 9. 1.1 Tallgrass Prairie Community

The interpretive plant community for this site is the reference plant community(1.1). The community is dominated by warm-season perennial tallgrasses such as little bluestem, big bluestem, eastern gamagrass and Indiangrass. Other major perennial grass species such as switchgrass, sideoats grama and silver bluestem are well dispersed through the site. Perennial forbs such as sunflowers (Simsia spp.), prairie clovers (Dalea spp.), bundleflowers (Desmanthus spp.), and daleas (Daleas spp.) are well represented throughout the community. This plant community evolved with a short duration of heavy use by large herbivores followed by long rest periods due to herd migration along with occasional fire. This state can go directly to the Shrubland Community (3.1), in the absence of fire or brush management to assist in suppressing the brush species, and still have the tallgrass component present in the community. With heavy grazing pressure and the subsequent removal of fire, the historic community will change into a Tall and Midgrass Prairie Community (1.2), a Short and Midgrass Prairie Community (2.1) or Shrubland Community (3.1). The changes within the grassland communities can change fairly rapid while the communities having an increase of woody plants are somewhat slower.

Figure 10. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 3587 | 5380 | 7173 |

| Forb | 448 | 673 | 897 |

| Shrub/Vine | 280 | 420 | 560 |

| Tree | 168 | 252 | 336 |

| Total | 4483 | 6725 | 8966 |

Figure 11. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6011, Warm-season perennial tallgrass prairie. The community is dominated by warm-season perennial tallgrasses with few shrubs, trees and forbs..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

Community 1.2

Tall and Midgrass Prairie Community

Figure 12. 1.2 Tall and Midgrass Prairie Community

This transitional community occurs with heavy yearlong grazing by large herbivores without the application of fire or brush management practices. The tallgrasses will start to disappear from the plant community. Brush not native to this site (mesquite, juniper, and pricklypear cactus, etc.) appear and become readily established. Cedar elm (Ulmus crassifolia), bumelia, and hackberry also start to increase in density and stature. Texas wintergrass (Nassella leucotricha) increases as brush canopy increases. It is more shade tolerant since most of growth occurs during the cool season when brush has lost its leaves. This plant community consists of less than 10 percent canopy of woody plants. Continuous heavy grazing by domestic livestock has accelerated the shift towards the Shrubland State (3.1). The tall and midgrass prairie community (1.2) can revert back to the Tallgrass Prairie Community (1.1) with conservation practices such as brush management, prescribed burning and/or prescribed grazing. Without prescribed burning and/or prescribed grazing, this plant community would continue to shift toward the Short and Midgrass Community (2.1) or Shrubland Community (3.1).

Figure 13. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 2690 | 3699 | 4708 |

| Forb | 560 | 785 | 1009 |

| Shrub/Vine | 392 | 532 | 673 |

| Tree | 168 | 252 | 336 |

| Total | 3810 | 5268 | 6726 |

Figure 14. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6012, Midgrass Prairie. Midgrass Prairie with increase of forbs, shrubs, and trees (5% canopy)..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

With heavy continuous grazing, no brush management, and no fires being applied to the tallgrass prairie community, it will shift to the tall/midgrass prairie community.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

With the application of Prescribed Grazing, Brush Management, and Prescribed Burning conservation practices, the tall/midgrass prairie community can be reverted back to the tallgrass prairie community.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 2

Short/Midgrass State

Dominant plant species

-

Texas live oak (Quercus fusiformis), tree

-

sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), grass

-

buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides), grass

Community 2.1

Short & Midgrass Prairie Community

Figure 15. 2.1 Short & Midgrass Prairie Community

The Short and Midgrass Prairie Community (2.1) consists of short and mid grasses with 5 to 15 percent canopy of woody plants. As this community matures, brush canopy along with grasses such as Texas wintergrass, threeawns (Aristida spp.) and annuals continues to increase. Warm-season perennial tallgrasses such as Indiangrass and switchgrass have all but disappeared. Continuous overgrazing by domestic livestock has accelerated the shift. The shift to this state has occurred due to the absence of fire or other means of brush suppression coupled with heavy grazing by domestic livestock. The grass species that dominate the site are mostly annual cool-season species. This state can be reverted back to near reference condition by some means of brush suppression and grazing management. Without this treatment the site will continue to shift toward more dense stands of brush This change can be anywhere from as little as one year to ten or more depending on the grass species present and degree of grazing management.

Figure 16. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 1681 | 2242 | 2690 |

| Forb | 560 | 729 | 897 |

| Shrub/Vine | 280 | 364 | 448 |

| Tree | 280 | 364 | 448 |

| Total | 2801 | 3699 | 4483 |

Figure 17. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6014, Mesquite/Juniper/Brushland Community. Consist of mixed grasses with greater than 50 percent canopy of woody plants..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 3 | 8 | 20 | 25 | 19 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

State 3

Shrubland State

Dominant plant species

-

Texas live oak (Quercus fusiformis), tree

-

Ashe's juniper (Juniperus ashei), tree

-

Texas wintergrass (Nassella leucotricha), grass

Community 3.1

Shrubland Community

Figure 18. 3.1 Shrubland Community

This plant community is a Shrubland Community (3.1) having greater than 20% woody canopy dominated by mesquite and or juniper. Other species present in small amounts are cedar elm, hackberry, and live oak. The herbaceous understory is almost nonexistent. Shade tolerant species such as Texas wintergrass tends to dominate the site where mesquite is the major woody plant. When the canopy of Juniper increases toward a cedar breaks type community most grasses have disappeared. Continuous grazing by domestic livestock has accelerated the shift. The tallgrass prairie can be restored by prescribed burning and prescribed grazing but will require many years of burning due to light fuel load of fine fuel and the absence of a seed source for the tall grasses. Chemical control alone is usually a good option for treatment on a large scale especially where a seed source is present. Mechanical treatment of this site along with seeding is a good when seeding is needed. Due to the presence of shade, the amount of grass cover is greatly reduced which in turn reduces forage production from the historic state.

Figure 19. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 908 | 1087 | 1267 |

| Forb | 504 | 605 | 706 |

| Shrub/Vine | 303 | 359 | 415 |

| Tree | 303 | 359 | 415 |

| Total | 2018 | 2410 | 2803 |

Figure 20. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6014, Mesquite/Juniper/Brushland Community. Consist of mixed grasses with greater than 50 percent canopy of woody plants..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 3 | 8 | 20 | 25 | 19 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Community 4.1

Cropland Community

Extensive conversion of the Clay Loam ecological site to cropland (primarily cotton and corn) occurred from the middle 1800s to the early 1900s. Some remains in cropland today – typically small grain production for stocker-cattle grazing. While restoration of this site to a semblance of the tallgrass prairie is possible with range planting, prescribed grazing, and prescribed burning - complete restoration of the historic climax community in a reasonable time is very unlikely due to deterioration of the soil structure and organisms. If cropping is abandoned, this land is usually planted to introduced grasses and forbs and managed as pastureland.

Figure 21. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Figure 22. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6102, Cool-Season Annual Grasses & Legumes. Oats, Rye, Wheat, Ryegrass, Clover and Vetch planted..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 11 | 13 | 19 | 21 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 9 |

Community 4.2

Pastureland Community

Figure 23. 4.2 Pastureland Community

This community is the result of mechanical brush control and reseeding using one or more introduced grass species. Introduced species such as kleingrass (Panicum coloratum) or one of the old world bluestems (Bothriochloa ischaemum var.) such as WW Spar or WB Dahl may be a part of the seed mixture. Due to the lack of diversity of plant species and presence of introduced species it will take a long time if ever for this state to again reach the historic state.

Figure 24. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 9. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 3587 | 5604 | 7622 |

| Forb | 448 | 560 | 673 |

| Total | 4035 | 6164 | 8295 |

Figure 25. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6015, Open Seeded Grassland Community. This state is usually the result of mechanical brush control and reseeding using one or more native grass species..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

Community 4.3

Native Seeding Community

This state is usually the result of mechanical brush control and range planting using one or more native grass species. An introduced species may be a part of the seed mixture, some of which can be invasive. This state also includes seeded cropland (not necessarily abandoned). Due to the lack of diversity of plant species such as forbs and native grasses along with the possible presence of introduced species, it will take a long time if ever for this state to again reach the historic state.

Figure 26. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 10. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 3811 | 5716 | 7622 |

| Forb | 448 | 673 | 897 |

| Total | 4259 | 6389 | 8519 |

Figure 27. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6015, Open Seeded Grassland Community. This state is usually the result of mechanical brush control and reseeding using one or more native grass species..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

Pathway 4.1A

Community 4.1 to 4.2

With pasture planting, the Cropland Community can shift to monocultures of pastureland.

Conservation practices

| Forage and Biomass Planting |

|---|

Pathway 4.1B

Community 4.1 to 4.3

With the application of various conservation practices such as Prescribed Grazing, Range Planting, and Prescribed Burning, the Cropland Community can shift to the Native Seeding Community.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting |

Pathway 4.2A

Community 4.2 to 4.1

With Crop Cultivation, the Pastureland Community can revert back to the Cropland Community phase.

Pathway 4.2B

Community 4.2 to 4.3

With Prescribed Grazing, Range Planting, and Prescribed Burning conservation practices, the Pastureland Community can be shifted to the Native Seeding Community.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting |

Pathway 4.3A

Community 4.3 to 4.1

With the application of brush management and crop cultivation, the Native Seeding Community can shift to the Cropland Community.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management |

|---|

Pathway 4.3B

Community 4.3 to 4.2

With Prescribed Grazing and Pasture Planting, the Native Seeding Community can be reverted to the Pastureland Community.

Conservation practices

| Forage and Biomass Planting | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

With heavy continuous grazing, no fires, and land being in idle conditions, the Tallgrass Prairie State shifts to the Short/Midgrass State.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 4

With Brush Management, Crop Cultivation, Range Planting, and Pasture Planting, the Tallgrass Prairie State can be converted into the Converted Land State.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

With the application of various conservation practices such as Prescribed Grazing, Brush Management, Range Planting, and Prescribed Burning, the Short/Midgrass State can revert back to the Tallgrass Prairie State.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting |

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

With heavy continuous grazing, idle and no fires, the Short/Midgrass State will shift to the Shrubland State.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

With Brush Management, Crop Cultivation, Range Planting, and Pasture Planting, the Short/Midgrass State can shift to the Converted Land State.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 2

With the application of various conservation practices, the Shrubland State may revert back to the Short/Midgrass State.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting |

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 1

With Range Planting,Prescribed Grazing and Prescribed Burning, the Converted Land State can be reverted to something very close to the Tallgrass Prairie State.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Range Planting | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Restoration pathway R4B

State 4 to 2

With heavy continuous grazing, no brush management, no fires, and land being idled, the Converted Land State would shift to the Short/Midgrass State.

Additional community tables

Table 11. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Tallgrass | 1524–3049 | ||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | 1524–3049 | – | ||

| 2 | Tallgrasses | 1031–2062 | ||||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 258–2062 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 258–2062 | – | ||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 258–2062 | – | ||

| eastern gamagrass | TRDA3 | Tripsacum dactyloides | 258–2062 | – | ||

| 3 | Midgrass | 258–516 | ||||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 258–516 | – | ||

| 4 | Midgrasses | 258–516 | ||||

| silver beardgrass | BOLAT | Bothriochloa laguroides ssp. torreyana | 129–516 | – | ||

| Texas cupgrass | ERSE5 | Eriochloa sericea | 129–516 | – | ||

| 5 | Cool-season grasses | 258–516 | ||||

| Canada wildrye | ELCA4 | Elymus canadensis | 85–516 | – | ||

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | 85–516 | – | ||

| Texas wintergrass | NALE3 | Nassella leucotricha | 85–516 | – | ||

| 6 | Mid/Shortgrasses | 258–516 | ||||

| purple threeawn | ARPUP9 | Aristida purpurea var. perplexa | 0–516 | – | ||

| Wright's threeawn | ARPUW | Aristida purpurea var. wrightii | 0–516 | – | ||

| buffalograss | BODA2 | Bouteloua dactyloides | 0–516 | – | ||

| hairy grama | BOHI2 | Bouteloua hirsuta | 0–516 | – | ||

| tall grama | BOHIP | Bouteloua hirsuta var. pectinata | 0–516 | – | ||

| fall witchgrass | DICO6 | Digitaria cognata | 0–516 | – | ||

| plains lovegrass | ERIN | Eragrostis intermedia | 0–516 | – | ||

| seep muhly | MURE2 | Muhlenbergia reverchonii | 0–516 | – | ||

| vine mesquite | PAOB | Panicum obtusum | 0–516 | – | ||

| Drummond's dropseed | SPCOD3 | Sporobolus compositus var. drummondii | 0–516 | – | ||

| slim tridens | TRMU | Tridens muticus | 0–516 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 7 | Forbs | 448–897 | ||||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 0–897 | – | ||

| white sagebrush | ARLUM2 | Artemisia ludoviciana ssp. mexicana | 0–897 | – | ||

| yellow sundrops | CASE12 | Calylophus serrulatus | 0–897 | – | ||

| American star-thistle | CEAM2 | Centaurea americana | 0–897 | – | ||

| whitemouth dayflower | COER | Commelina erecta | 0–897 | – | ||

| croton | CROTO | Croton | 0–897 | – | ||

| prairie clover | DALEA | Dalea | 0–897 | – | ||

| purple prairie clover | DAPU5 | Dalea purpurea | 0–897 | – | ||

| Illinois ticktrefoil | DEIL2 | Desmodium illinoense | 0–897 | – | ||

| blacksamson echinacea | ECAN2 | Echinacea angustifolia | 0–897 | – | ||

| Engelmann's daisy | ENPE4 | Engelmannia peristenia | 0–897 | – | ||

| Leavenworth's eryngo | ERLE11 | Eryngium leavenworthii | 0–897 | – | ||

| snow on the mountain | EUMA8 | Euphorbia marginata | 0–897 | – | ||

| beeblossom | GAURA | Gaura | 0–897 | – | ||

| hoary false goldenaster | HECA8 | Heterotheca canescens | 0–897 | – | ||

| Maximilian sunflower | HEMA2 | Helianthus maximiliani | 0–897 | – | ||

| bluet | HOUST | Houstonia | 0–897 | – | ||

| coastal indigo | INMI | Indigofera miniata | 0–897 | – | ||

| trailing krameria | KRLA | Krameria lanceolata | 0–897 | – | ||

| dotted blazing star | LIPU | Liatris punctata | 0–897 | – | ||

| Nuttall's sensitive-briar | MINU6 | Mimosa nuttallii | 0–897 | – | ||

| yellow puff | NELU2 | Neptunia lutea | 0–897 | – | ||

| cobaea beardtongue | PECO4 | Penstemon cobaea | 0–897 | – | ||

| groundcherry | PHYSA | Physalis | 0–897 | – | ||

| rhynchosida | RHYNC5 | Rhynchosida | 0–897 | – | ||

| prairie coneflower | RUFUP | Rudbeckia fulgida var. palustris | 0–897 | – | ||

| pitcher sage | SAAZG | Salvia azurea var. grandiflora | 0–897 | – | ||

| amberique-bean | STHE9 | Strophostyles helvola | 0–897 | – | ||

| false gaura | STLI2 | Stenosiphon linifolius | 0–897 | – | ||

| white heath aster | SYERE | Symphyotrichum ericoides var. ericoides | 0–897 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 8 | Shrubs/Vines | 280–560 | ||||

| catclaw acacia | ACGR | Acacia greggii | 0–560 | – | ||

| stretchberry | FOPU2 | Forestiera pubescens | 0–560 | – | ||

| fragrant sumac | RHAR4 | Rhus aromatica | 0–560 | – | ||

| winged sumac | RHCO | Rhus copallinum | 0–560 | – | ||

|

Tree

|

||||||

| 9 | Trees | 168–336 | ||||

| hackberry | CELTI | Celtis | 0–336 | – | ||

| plum | PRUNU | Prunus | 0–336 | – | ||

| Texas red oak | QUBU2 | Quercus buckleyi | 0–336 | – | ||

| Texas live oak | QUFU | Quercus fusiformis | 0–336 | – | ||

| bully | SIDER2 | Sideroxylon | 0–336 | – | ||

| Hercules' club | ZACL | Zanthoxylum clava-herculis | 0–336 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

The historic tallgrass prairie was habitat to migratory bison herds. White-tailed deer, turkey, bobcats and coyotes along with resident and migratory birds and small mammals find suitable habitat today. Domestic livestock are the dominant grazer of the site today. As the prairie changes through the various vegetative states towards the shrubland, the quality of the habitat may improve for some species such as songbirds, deer and goats and decline for others such as cattle. It is often the objective of many land owners to manage for a plant community that wildlife species can exist along with domestic livestock. This can be done with a carefully planned grazing and brush management program. Management practices such as brush management, prescribed burning and prescribed grazing will be required in order to maintain the vegetative state that provides the most optimum habitat quality for the desired animal species.

Hydrological functions

Peak rainfall periods occur in April, May, June, September and October. Rainfall amounts may be high (3 to 10 inches per event) and events may be intense. The soils of this site are deep. Periods of 60 plus days of little or no rainfall during the growing season are common. During periods of good rainfall with good grass cover, water infiltrates to the limestone rock below and moves to lower elevations and emerges as seeps and springs. The hydrology of this site may be manipulated with management to yield higher runoff volumes or greater infiltration.. Management for less herbaceous cover will favor higher surface runoff while dense herbaceous cover favors deeper infiltration. Potential movement of soil due to erosion, pesticides and both organic and inorganic nutrients (fertilizer) should always be considered when managing for higher volumes of surface runoff.

Recreational uses

Hunting, hiking, camping, equestrian, bird watching and off road vehicle use.

Wood products

None

Other products

None

Other information

None

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented here has been derived from NRCS clipping data and field observations of range trained personnel: James Luton RMS, Montague; William Donham, DC, Weatherford; Kent Ferguson RMS, Weatherford; Dan Caudle

References

-

. 2021 (Date accessed). USDA PLANTS Database. http://plants.usda.gov.

-

Bailey, V. 1905. Biological Survey of Texas. North American Fauna 25:1–222.

Other references

Ajilvsgi, Geyata, Wildflowers of Texas, Shearer Publishing, Fredericksburg, Texas, 1984

Anderson, C. A. et.al, The Western Range: Letter from Sec. of Agr. in Response to Senate Resolution No. 289, A Report on the Western Range, A great Neglected Natural Resource, Document No. 199, United States Government Printing Office, Washington , April 24, 1936

Bentley, H. L., Cattle Ranges of the Southwest: A History of the Exhaustion of the Pasturage and Suggestions for Its Restoration, USDA Farmer’s Bulletin No. 72, Abilene, Texas, 1898

Bogusch, E. R., Brush Invasion in the Rio Grande Plain of Texas, Texas Journal of Science, 1952

Bonnell, G. W., Topographical descriptions of Texas, Clark, Wing and Brown, Austin, 1840

Box, T. W., Brush, fire and West Texas Rangeland, Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference, 1967

Bray, W. L., Forest Resources of Texas, 600 Acres Cedar Brake Burned at Marble Falls July, 1901, USDA, Bulletin No. 47 Bureau of Forestry,

Bray, W. L., The timber of the Edwards Plateau of Texas: It’s Relation to Climate, Water Supply and Soil, USDA, Forest Bulletin No 49, 1904

Clambey, Gary K, The Prairie: Past, Present, and Future, Proceedings of the Ninth North American Prairie Conference, Tri-College University Center for Environmental Studies, Fargo North Dakota, October, 1986

Clements, Dr. Frederic E., Dynamics of Vegetation, The H. W. Wilson Company, New York, 1949

Clements, Frederic E., Plant Succession and Indicators: A Definitive Edition of Plant Succession and Plant Indicators, The H. W. Wilson Company, New York City 1928

Collins, O. B., Smeins, Fred E & Johnson, M.C., Plant Communities of the Blackland Prairie of Texas, In Prairie: A Multiple View, University of North Dakota Press, Grand Forks, North Dakota, 1975

Coranado, Francisco V., Early Spanish Explorations of New Mexico and Texas, Journal of Pedro de Castenda, who was the historian for the Expedition of Francisco V. Coronado, April, 1541

Custis, Peter & Freeman, Jefferson and Southwestern Exploration: The Freeman and Curtis Accounts of the Red River Expedition of 1806, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1984

Custis, Peter, The Ecology of the Red River in 1806: Peter Custis and Early Southwestern Natural History, Southern Historical Quarterly, 1806

Dary, David A., The Buffalo Book: The Saga of an American Symbol, A Spellbinding recreation of lore, legend and fact about the great American Bison,

Diamond, David & Smeins, Fred E., Remnant Grassland Vegetation and Ecological Affinities of the Upper Coastal Prairie of Texas, The American Midland Naturalist 110, The University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, August 28, 1984

Diamond, David D., Texas Prairies: Almost Gone, Almost Forgotten, Texas Parks and Wildlife, Vol. 48, No. 3, March, 1990

Diggs, George M., Liscomb, & O’Kennor, Skinners & Mahler’s Illustrated Flora of North Central Texas, Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Fort Worth, Texas, 1999

Dyksterhuis, E. J., The Vegetation of the Fort Worth Prairie, Contribution No 146 from the Department of Botany, University of Nebraska, January, 1946

Flores, Dan, Indian Use of Range Resources, Texas Tech Department of History, 20th Annual Range Management Conference, Lubbock, Texas, About 1990

Flores, Dan, The Red River Branch of the Alabama-Coushatta Indians: An Ethnohistory, Southern Studies Journal 16, Spring 1977

Foreman, Grant, Adventure on the Red River, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1937

Foster, J.H., The Spread of Timbered Areas in Central Texas, Journal of Forestry No. 15, 1917

Gard, Wayne, The Chisholm Trail, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1954

Geiser, S. W., Naturalists of the Frontier, Southern Methodist University Press, Dallas, Texas 1948

Gey, Kenneth, et.al, White-tailed Deer, Their Foods and Management in the Cross Timbers, A Samuel Roberts Nobel Foundation Publication, 1991

Gibson, A.M., From the Brazos to the North Fork: The Autobiography of Otto Koeltzow, The Chronicles of Oklahoma, University of Oklahoma, Part 1 & 2, Vol. XL, No. 1, 1962

Hignight, K.W., et. Al, Grasses of the Texas Cross Timbers and Prairies, MP-1657, Texas Agricultrual Experiment Station, College Station, Texas 1988

Jackson, A.S., Wildfires in the Great Plains Grassland, Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference, 1965

Jenkins, John Holmes III, Recollections of Early Texas, The Memoirs of John Holland Jenkins, University of Texas Press, Austin Texas, 1958

Johnston, M.C, Past and Present Grasslands of Southern Texas and Northeastern Mexico, Ecology 44, 1963

Jordan, Gilbert J., Yesterday in the Texas Hill Country, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, Texas, 1979

Jordan, Terry G., German Seed in Texas Soil, Immigrants Farmers in Nineteenth-Century Texas, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, 1966

Kelton, Elmer, History of Rancher Use of Range Resources, 20th Annual Ranch Management Conference, Lubbock, Texas, September 30, 1983

Kelton, Elmer, West Texas: From Settlement to the Present, Talk presented to Texas Section, Society for Range Management, San Angelo, Texas October 8, 1993

Kendall, G. W., Narrative of the Texas Sante Fe Expedition, Vol. I, Wiley and Putman, London, 1844

King, I. M., John Q. Meusebach, German Colonizer in Texas, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, 1967

Kruger, M.A. P., Second Fatherland: The Life and Fortunes of a German Immigrant, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, Texas 1976

Kurlansky, Mark, Salt – A World History, Walter Publishing Company, New York, NY, USA 2002

Launchbaugh, J.L., Vegetational Changes in the San Antonio Prairie Associated with Grazing, retirement from grazing, and abandonment from cultivation, Ecol. Monogr., 25, 1955

Lehmann, V. W., Fire in the Range of the Attwater’s Prairie Chicken, Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference, 1965

Marcy, R. B., His diary as captain of 5th Infantry U.S. Army, 31st Cong., 1st Sess., U. S. Senate Exec. Doc., Vol. 14, 1849 –1850

Marcy, R. B., Thirty Years of Army Life on the Border, Harper & Fros., Franklin Square, New York, 1866

Marks, Paula Mitchell, The American Gold Rush Era: 1848 – 1900, William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, 1994

Martin, P.S., Vanshings, and Future of the Prairie, Geoscience and Man, 1965

Moorehead, M.L., Commerce of the Prairies by Josiah Gregg, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma 1954

Murrah, David J., C. C. Slaughter, Rancher, Banker, Baptist, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas 1981

Newcomb, S.P., Journal of a trip from the Clear Fork of the Brazos to the San Saba River, Addenda in Interwoven by Sallie R. Matthews, Reprint by Hertzog, El Paso, Texas 1958

Norton-Griffiths,M., The Influence of Grazing, Browsing, and Fire on the Vegetation of the Serengeti, In Serengeti Dynamics of an Ecosystem, Edited by A.R.E Barnes and Company, New York, 1976

Nuez, Cabeza de Vaca, The Journey of Alvar Nuez Cabeza de Vaca and His Companions for Florida to the Pacific 1528 – 1536, Edited with Introduction by A. F. Bandeleir, A.S. Barnes and Company, New York, 1905

Odum, E.P., Fundamentals of Ecology, 3rd Edition, W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1971

Olmsted, Frederick Law, A Journey through Texas, Or, A Saddle-Trip on the Southwestern Frontier, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, 1857

Ormsby, Waterman L., The Butterfield Overland Mail, The Huntington Library San Marino, California, 1942

Parker, William B., Notes Taken during the Expedition through Unexplored Texas: With Capitan Randolph March and Major Robert S. Neighbors in 1854. Transcript given Archer County Soil Conservation Service by K.F. Neighbors

Parker, A.A., Trip to West and Texas, Comprising a Journey of 8,000 Miles, Through New York, Michigan, Illinois, Missouri, Louisiana and Texas in the Autumn and Winter of 1834 – 1835, 2nd Edition William White, Concord, New Hampshire 1836

Riskind, David H. & Diamond, David D., Edwards Plateau Vegetation, B Amos & F.R. Gehlbach, Baylor University Press, 1988

Roemer, F, Texas with Particular Reference to German Immigrants: The Physical Appearance of the Country, Standard Printing Company, San Antonio, Texas 1935

Sauer, C. O., Man’s Dominance by Use of Fire, Geoscience and Man, 1975

Smeins, Fred E. & Diamond, David D., Composition, Classification and Species Response Patterns of Remnant Tallgrass Prairies in Texas, The American Midland Naturalist 113, The University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, 1985

Smeins, Fred E. & Diamond, David D., Remnant Grasslands of the Fayette Prairie, The American Midland Naturalist 110, The University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, 1983

Smith, Jared.G., Grazing problems in the Southwest and How to Meet Them, USDA, Division Agronomy, Bulletin No. 16, 1899

Spaeth, Kenneth E, Grazingland Hydrology Issues: Perspectives for the 21st Century, Published by the Society for Range Management, Denver, Colorado, 1996

Stefferud, Alfred, Grass: The Yearbook of Agriculture 1948, USDA, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington 1948

Stoddart, Laurence A., Range Management, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., New York, 1955

Terry, J. Dale, Explorations of the Big Wichita, Etc., Terry Bros., Printers, Wichita Falls, Texas August, 1962.

Tharp, B. C., Structure of the Texas Vegetation East of the 98th Meridian, University of Texas Bulletin No 2606, 1926

Unknown, Author, Saga of the Buffalo: From Multitudes to Near Extinction, Ranch Magazine, San Angelo, Texas November, 1994

Unknown, Timber of the Edwards Plateau of Texas, Cedar Brake Fires, More Cedars by Fire than by the Axe 1880 – 1904, USDA, Bulletin No. 49, Bureau of Forestry

Vasey, Dr. George, Report of an Investigation of the Forage Plants of Western Texas, USDA Publication, January 17, 1888, Houston, Texas

Vine, Robert A., Trees, Shrubs and Wood Vines of the Southwest, University of Texas, Austin, Texas, 1960

Webb, W. P., The Great Plains, Gossett and Dunlap, New York, 1965

Williams, Jesse Wallace, Old Texas Trails, USA, Eakin Press, Burnet, Texas 1979

Wright, Henry A., Fire Ecology: United States and Southern Canada, Awiley-Interscience Publication, New York, 1982

Technical Review:

Homer Sanchez, State Rangeland Management Specialist - Texas

Mark Moseley, State Rangeland Management Specialist - Oklahoma

Kent Ferguson, Zone Rangeland Management Specialist

Dr. Jack Eckroat, Grazing Lands Specialist - Oklahoma

Justin Clary, Rangeland Management Specialist

Contributors

Edits to legacy content by Colin Walden, Stillwater Soil Survey Office

Acknowledgments

Site Development and Testing Plan:

Future work, as described in a Project Plan, to validate the information in this Provisional Ecological Site Description is needed. This will include field activities to collect low, medium and high intensity sampling, soil correlations, and analysis of that data. Annual field reviews should be done by soil scientists and vegetation specialists. A final field review, peer review, quality control, and quality assurance reviews of the ESD will be needed to produce the final document. Annual reviews of the Project Plan are to be conducted by the Ecological Site Technical Team.

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Lem Creswell, Zone RMS, NRCS, Weatherford Texas |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | 817-596-2865 |

| Date | 03/01/2006 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. Current or past formation of rills are not present. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

None. This site rarely has flow patterns. Some are expected around surface obstacles. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

None. Some minor pedestalling may occur in the shallow lower production portions of the site. Rarely should they be over 1/4 inches height. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

0 to 10 percent bare ground. Small and non-connected areas. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

Drainages are represented as natural stable channels, vegetation common and no signs of erosion. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Minimal and short. Less than 6 inches. Only associated with water flow patterns following extremely high intensity rainfall. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Stable. No reduction in soil stability in plant interspaces or slight reduction throughout the site. Stabilizing agents as expected. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

Grayish brown clay loam surface 6 to 16 inches thick with subrounded to angular pebbles, cobbles, and stones and strong granular / moderately blocky structure. Soil Organic Matter is 1 to 4 percent. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

High canopy, basal cover, and density with small interspaces make rainfall impact negligible. This site has well drained soils, slowly permeable with 1 to 12 percent slopes which allows negligible runoff and erosion. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None to minimal, not restrictive to water movement and root penetration. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm-season tallgrasses >>Sub-dominant:

Warm-season midgrasses >Other:

Forbs > Shrubs/Vines = Trees > Warm-season shortgrasses > Warm-season sodgrassesAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Grasses due to their growth habit will exhibit some mortality and decadence though very slight. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Litter is dominantly herbaceous and covers almost all plant and rock interspaces. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

4000 to 8000 #/acre. 4000 pounds in below average years, 6000 pounds in normal years and 8000 pounds in above average years. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Ashe juniper, pricklypear, mesquite and King Ranch bluestem are the primary invaders. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Only drought, natural herbivory and/or wildfires decrease reproductive capability of any functional groups in the HCPC state.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.