Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R085AY562TX

Sandy Loam 30-38" PZ

Accessed: 03/12/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 085A–Grand Prairie

The Grand Prairie MLRA is characterized by predominately loam and clay loam soils underlain by limestone and shale. Topography transitions from steeper ridges and summits of the Lampasas Cut Plain on the southern end to the more rolling hills of the Fort Worth Prairie to the north. The Arbuckle Mountain area in Oklahoma is also within this MLRA.

Classification relationships

This ecological site is correlated to soil components at the Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) level which is further described in USDA Ag Handbook 296.

Ecological site concept

These sites occur on deep sandy loam soils over sandstone. The reference plant community includes a post oak/blackjack oak savannah with native tallgrasses dominating the site. Native forbs and few shrub species also occur. If fire and/or brush management is removed, the woody species may increase on the site.

Associated sites

| R085AY185TX |

Shallow 30-38" PZ The Shallow site is often upslope from this site. It differs from the Sandy Loam site by having shallow, dark grayish-brown clay loam soils formed from limestone, not alluvium. |

|---|

Similar sites

| R085AY181TX |

Loamy Bottomland 30-38" PZ The Loamy Bottomland site is similar to the Sandy Loam site in that it is also formed from alluvium. It differs from the Sandy Loam site by having dark grayish-brown clay loam soils, slopes of 0 to 2%, and its location on floodplains. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Quercus stellata |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Schizachyrium scoparium |

Physiographic features

This site occurs on gently sloping to moderately steep slopes with well defined swales and water courses. Slopes range from 0 to 8 percent but are dominantly 3 to 5 percent. Some of the steeper areas are dissected by gullies. The site may include small ridges with some rock outcropping. The site includes areas of former cultivated land which has suffered from severe erosion. Elevation ranges from 350 to 2500 feet.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Ridge

|

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 351 – 2,499 ft |

| Slope | 8% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate is subhumid subtropical and is characterized by hot summers and relatively mild winters. Tropical maritime air controls the climate during spring, summer and fall. In winter and early spring, frequent surges of Polar Canadian air cause sudden drops in temperatures and add considerable variety to the daily weather. The average first frost should occur around November 5 and the last freeze of the season should occur around March 19.

The average relative humidity in mid-afternoon is about 60 percent. Humidity is higher at night, and the average at dawn is about 80 percent. The sun shines 75 percent of the time possible during the summer and 50 percent in winter. The prevailing wind direction is from the south and highest windspeeds occur during the spring months.

Approximately two-thirds of annual rainfall occurs during the April to September period. Rainfall during this period generally falls during thunderstorms, and fairly large amounts of rain may fall in a short time. The driest months are usually July and August.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 256 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 289 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 38 in |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

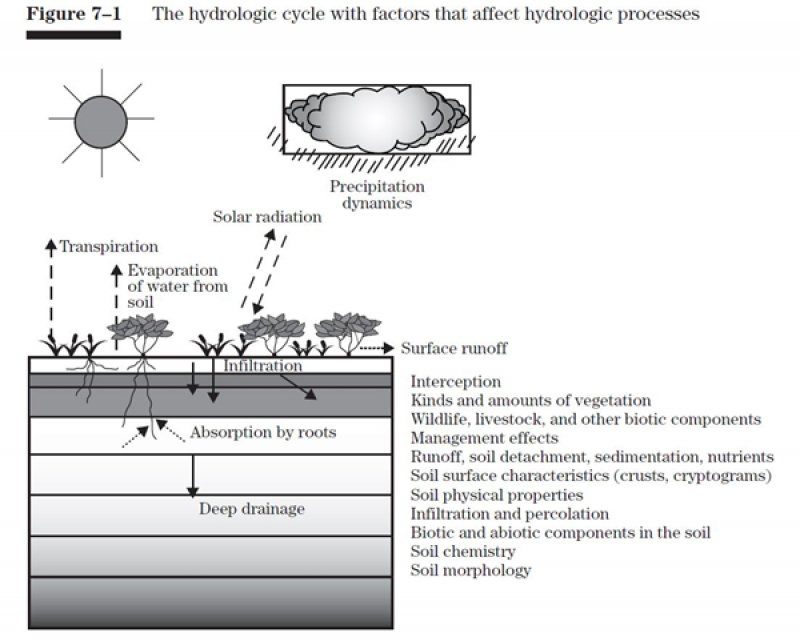

Influencing water features

These sites receive some water from run off of adjacent sites and also shed some water to sites downslope. The presence of deep rooted tallgrasses help facilitate infiltration of rainfall into the soil profile.

Figure 3. Hydrologic Cycle

Soil features

The Sandy Loam 30-38” PZ site is composed of nearly level to sloping soils on uplands. The soils have a sandy loam or loamy surface layer, and loamy or clayey underlying layer. They are moderately well-drained to well-drained. These deep soils are moderately to moderately slowly permeable with a high available water capacity. The depth and openness of the soils permit maximum penetration of grass roots and free intake of food and water.

The dominant soil series for this site include Hext, Cisco, Minwells, and Bastsil.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Stony fine sandy loam (2) Very fine sandy loam (3) Loam |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Moderately well drained to well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate to moderately slow |

| Soil depth | 20 – 72 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

4 – 7 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

10% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

4.5 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

2 – 70% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

23% |

Ecological dynamics

The Sandy Loam 30-38” PZ ecological site is a post oak (Quercus stellata) and blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica) savannah with tall and midgrasses. The reference plant community is a fire-influenced mosaic of oak plant communities, interspersed with a high diversity of tallgrasses, midgrasses, and perennial forbs. Improper grazing management will result in a reduction of tallgrasses offset by an increase in midgrasses, unpalatable forbs, and woody species. A lack of fire and brush management will result in a rapid increase in woody species until the site is dominated by woody species and the canopy shades out most understory species.

Continued degradation of the site will result in the site crossing a threshold to a shrubland community characterized by invasive shrubs, mid and shortgrasses, and unpalatable forbs. Bare ground, erosion, and water flow patterns will increase. Forage production will decline. Over time the size and amount of eroded areas will increase as the A horizon erodes.

Precipitation patterns are highly variable. Long-term droughts, occurring three to four times per century, cause shifts in species composition by causing die-off of seedlings, less drought-tolerant species, and/or some woody species. Droughts also reduce biomass production and create open space, which is colonized by opportunistic species when precipitation increases. Wet periods allow tallgrasses to increase in dominance.

Natural vegetation on the uplands in MLRA 85 is predominantly tall warm-season perennial bunchgrasses with lesser amounts of midgrasses and shortgrasses. This Sandy Loam site was historically dominated by little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), with other tall grasses such as big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) making up a minor portion of the plant community. Midgrasses such as sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), tall dropseed (Sporobolus compositus), cane bluestem (Bothriochloa barbinodis), and silver bluestem (Bothriochloa saccharoides), Texas wintergrass (Nassella leucotricha), and slim tridens (Tridens muticus) make up about 20% of the production of this site. A wide variety of forbs add to the diverse native plant community. Additionally, several oak (Quercus spp.), elm (Ulmus spp.), and hackberry (Celtis spp.) tree species make up an important part of the savannah community.

The northernmost portion of the Grand Prairie MLRA is still relatively free from the widespread invasion of brush that has occurred in other parts of the state, including the southern part of the MLRA. Juniper (cedar) (Juniperus spp.), honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa), pricklypear (Opuntia spp.), and scrub oak (Quercus sinuata) have increased to the point of dominance in some locations, especially on shallow, rocky slopes.

Pre-settlement influences included grazing or browsing by endemic pronghorn antelope, deer and migratory bison, severe droughts, and frequent fires. Wright and Bailey (1982) reported that there are no reliable records of fire frequency in the Great Plains grasslands because there are no trees to carry fire scars from which to estimate fire frequency. A natural fire frequency of 7 to 10 years seems reasonable for this site.

Rangeland and pastureland are grazed primarily by beef cattle. Horse numbers are increasing rapidly in the region, and in recent years goat numbers have increased significantly. There are some areas where sheep are locally important. Whitetail deer, wild turkey, bobwhite quail, and dove are the major wildlife species, and hunting leases are a major source of income for many landowners in this area.

The Sandy Loam site has deep soils that lend to cultivation. This site is also frequently planted with tame pasture species, namely bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), kleingrass (Panicum coloratum), King Ranch bluestem (Bothriochloa ischaemum), and other Old World bluestems (Bothriochloa spp.), which are often seeded either as monocultures or interseeded with native species.

Rangeland Health Reference Worksheets have been posted for this site on the Texas NRCS website (www.tx.nrcs.usda.gov) in Section II of the eFOTG under (F) Ecological Site Descriptions (ESDs).

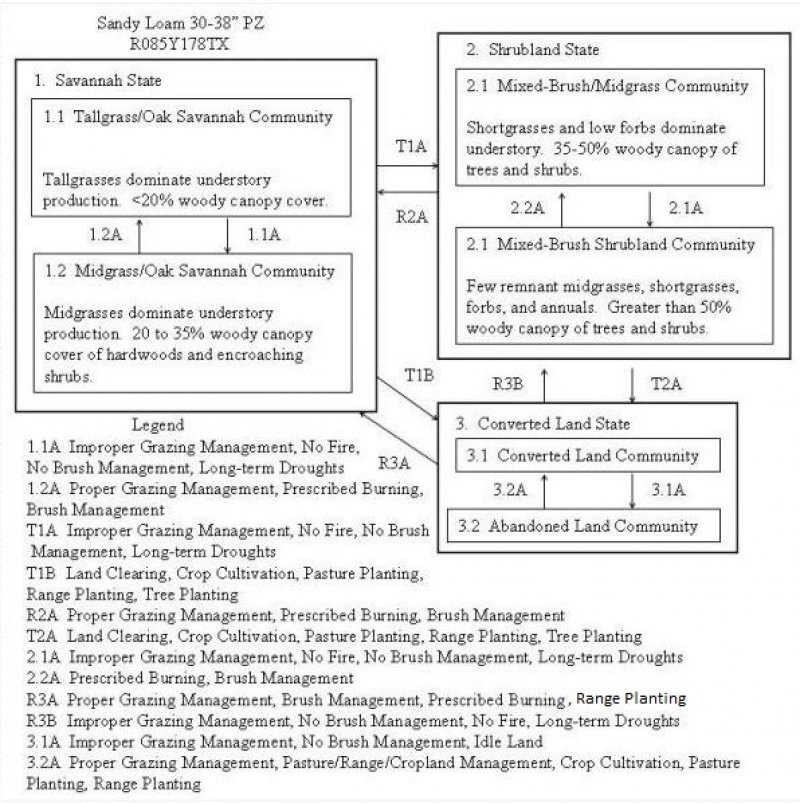

Plant Communities and Transitional Pathways

A state and transition model for the Sandy Loam ecological site is depicted in Figure 1. Thorough descriptions of each state and transition and of each plant community and pathway follow the model. This model is based on available experimental research, field observations, and interpretations by experts. It is likely to change as knowledge increases.

The plant communities will differ across the MLRA due to the naturally occurring variability in weather, soils, and aspect. The biological processes on this site are complex. Therefore, representative values are presented in a land management context. The species lists are representative and are not botanical descriptions of all species occurring, or potentially occurring, on this site. They are not intended to cover every situation or the full range of conditions, species, and responses for the site.

State and transition model

Figure 4. R085XY562TX

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Savannah State

Community 1.1

Tallgrass/Oak Savannah Community

Figure 5. 1.1 Tallgrass/Oak Savannah Community

The Tallgrass/Oak Savannah Community requires fire and/or brush control to maintain woody species cover below 20%. This community will shift to the Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community when there is continued growing season stress on palatable grass species. These stresses include improper grazing management that creates insufficient critical growing season deferment, excess intensity of defoliation, repeated, long-term growing season defoliation, long-term drought, and/or other repeated critical growing season stress. Increaser species (midgrasses and woody species) are generally endemic species released by disturbance. Woody species canopy exceeding 20% and/or dominance of tallgrasses falling below 50% of species composition indicate a transition to the Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community. Community 1.1 can be maintained through the implementation of brush management combined with properly managed grazing that provides adequate growing season deferment to allow establishment of tallgrass propagules and/or the recovery of vigor of stressed plants. The driver for community shift 1.1A for the herbaceous component is improper grazing management. The driver for the woody component is lack of fire and/or brush control.

Figure 6. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 2800 | 4000 | 5200 |

| Shrub/Vine | 350 | 500 | 650 |

| Forb | 350 | 500 | 650 |

| Total | 3500 | 5000 | 6500 |

Figure 7. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6020, Tallgrass Oak Savannah Community. The plant community is a fire climax savannah composed of warm-season perennial tallgrasses and scattered post oaks..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

Community 1.2

Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community

The Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community (1.2) typically results from improper cattle grazing management over a long period of time combined with a lack of brush control. Indigenous or invading woody species increase on the site (with or without fire). In the Tallgrass-Oak component keep woody canopy cover restricted to mottes within the savannah and 20 percent or less woody canopy cover. When the Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community (1.2) is continually overgrazed and fire is excluded, the community crosses a threshold to the Shrubland State, which is dominated by woody plants. Important grasses are little bluestem, sideoats grama, silver bluestem, tall dropseed, hairy grama, and Texas wintergrass. Texas wintergrass, hairy grama, and less palatable forbs begin replacing the midgrasses. Some of the perennial forbs persist, but less palatable forbs will increase. Woody canopy varies between 20 and 35 percent, depending on the severity of grazing, fire interval, and availability of increaser species. Numerous shrub and tree species will encroach because overgrazing by livestock has reduced grass cover, exposed more soil, and reduced grass fuel for fire. Typically, trees such as oaks and ash (Fraxinus spp.) will increase in size, while other tree and shrub species such as bumelia (Sideroxylon spp.), sumacs, elbowbush (Forestiera pubescens), agarito (Mahonia trifoliolata), honey mesquite, juniper, and pricklypear will increase in density. Brown and Archer (1999) concluded that even with a healthy and dense stand of grasses, woody species will populate the site and eventually dominate the community. To control woody species populations, prescribed grazing and/or browsing and fire can be used to control smaller shrubs and trees, and mechanical removal of larger shrubs and trees may be necessary in older stands. Heavy continuous grazing will reduce plant cover, litter, and mulch. Bare ground will increase and expose the soil to erosion. Litter and mulch will move off-site as plant cover declines. Increasing woody dominants are oaks, honey mesquite, and Ashe’s juniper. Once the tallgrasses have been eliminated from the site, woody species cover exceeds 35 percent canopy cover, and the woody plants within the grassland portion of the savannah reach fire-resistant size (about 3 feet in height), the site crosses a threshold into the Shrubland State (2) and the Mixed-Brush/Midgrass Community (2.1). Until the Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community (1.2) crosses the threshold into the Mixed-Brush/Midgrass Community (2.1), this community can be managed back toward the reference community(1.1) through the use of cultural practices including prescribed grazing, prescribed burning, and strategic brush control. It may take several years to achieve this state, depending upon climate and the aggressiveness of the treatment. Once invasive woody species begin to establish, returning fully to the reference is difficult, but it is possible to return to a similar plant community. Potential exists for soils to erode to the point that irreversible damage may occur. If soil-holding herbaceous cover decreases to the point that soils are no longer stable, the shrub overstory will not prevent erosion of the A and B soil horizons. This is a critical shift in the ecology of the site. Once the A horizon has eroded, the hydrology, soil chemistry, soil microorganisms, and soil physics are altered to the point where intensive restoration is required to restore the site to another state or community. Simply changing management (improving grazing management or controlling brush) cannot create sufficient change to restore the site within a reasonable time frame.

Figure 8. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 1950 | 2600 | 3250 |

| Shrub/Vine | 600 | 800 | 1000 |

| Forb | 450 | 600 | 750 |

| Total | 3000 | 4000 | 5000 |

Figure 9. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6021, Tall & Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community. The tallgrasses will start to disappear and be replaced by midgrasses. Invader brush species appears and becomes established..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

The Tallgrass/Oak Savannah Community requires fire and/or brush control to maintain woody species cover below 20%. This community will shift to the Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community when there is continued growing season stress on palatable grass species. These stresses include improper grazing management that creates insufficient critical growing season deferment, excess intensity of defoliation, repeated, long-term growing season defoliation, long-term drought, and/or other repeated critical growing season stress. Increaser species (midgrasses and woody species) are generally endemic species released by disturbance. Woody species canopy exceeding 20% and/or dominance of tallgrasses falling below 50% of species composition indicate a transition to the Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community. Community 1.1 can be maintained through the implementation of brush management combined with properly managed grazing that provides adequate growing season deferment to allow establishment of tallgrass propagules and/or the recovery of vigor of stressed plants. The driver for community shift 1.1A for the herbaceous component is improper grazing management. The driver for the woody component is lack of fire and/or brush control.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

The Midgrass/Oak Savannah Community will return to the Tallgrass/Oak Savannah Community with brush control and grazing management that provides sufficient critical growing season deferment in combination with proper grazing intensity. Favorable moisture conditions will facilitate or accelerate this transition. The understory component may return to dominance by tallgrasses in the absence of fire (at least until shrub canopy cover reaches 50%). Reduction of the woody component to 20% or less canopy cover will require inputs of fire and/or brush control. The understory and overstory components can act independently when canopy cover is less than 35%, i.e., an increase in shrub canopy cover can occur while proper grazing management creates an increase in desirable herbaceous species. The driver for community shift 1.2A for the herbaceous component is proper grazing management, while the driver for the woody component is fire and/or brush control.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 2

Shrubland State

Community 2.1

Mixed-Brush/Midgrass Community

The Mixed-Brush/Midgrass Community (2.1) presents a 35 to 50 percent woody plant canopy, with post oak and blackjack oak dominating the oak mottes and honey mesquite and Ashe’s juniper invading the former grassland areas. The community loses its savannah appearance with invasive shrubs beginning to fill the open grassland portion of the savannah. The oak mottes remain, but are no longer the only areas with trees. It is the result of continuous improper grazing by livestock and a lack of fire. In areas where high deer densities occur, heavy browsing can decrease preferred woody plants. There is a continued decline in diversity of the grassland component and an increase in woody species such as sumac. Unpalatable forbs such as western ragweed (Ambrosia psilostachya) increase in species composition. Annual herbage production decreases due to a decline in soil structure and organic matter and has shifted toward the woody component. All unpalatable woody species have increased in size and density. Honey mesquite is an early increaser throughout the MLRA. Redberry juniper (Juniperus pinchotii) occurs only in the southern counties of the MLRA and eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) occurs only in the northern portion. Ashe’s juniper occurs mostly in the southern portion, but can be found throughout the MLRA. Many of the reference community (1.1) shrubs are still present. Sideoats grama and other desirable midgrasses decrease to the point that grasses no longer form the dominant component. Shortgrasses such as red lovegrass (Eragrostis secundiflora), purple threeawn (Aristida purpurea), tumblegrass (Schedonnardus paniculatus), and tumble windmillgrass (Chloris verticillata) increase. Forbs such as curlycup gumweed (Grindelia squarrosa), western ragweed, silverleaf nightshade (Solanum elaeagnifolium), and thistles increase in species composition. Unpalatable invaders occupy the interspaces between trees and shrubs. Plant vigor and productivity of the grassland component is reduced due to competition for nutrients and water from woody plants. As the grassland vegetation declines, more soil is exposed, leading to crusting and erosion. In this vegetation type, erosion can be severe. Higher rainfall interception losses by the increasing woody canopy combined with evaporation and runoff can reduce the effectiveness of rainfall. Soil organic matter and soil structure decline within the interspaces, but soil conditions improve under the woody plant cover. Some soil loss can occur during rainfall events. Annual primary production is approximately 2,000 to 3,500 pounds per acre. In this plant community, annual production is balanced between herbaceous plants and woody species. Browsing animals such as goats and deer can find fair food value if browse plants have not been grazed excessively. Forage quantity and quality for cattle is low. Unless brush management and proper grazing management are applied at this stage, woody canopy will exceed 50 percent, causing the community to convert to the Mixed-Brush Shrubland Community (2.2). The trend cannot be reversed with proper grazing management alone.

Figure 10. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 900 | 1215 | 1575 |

| Shrub/Vine | 800 | 1080 | 1400 |

| Forb | 300 | 405 | 525 |

| Total | 2000 | 2700 | 3500 |

Figure 11. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6022, Oak/Juniper/Midgrass Community. Consists of midgrasses with ten to twenty percent canopy of woody plants..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 3 | 8 | 20 | 25 | 19 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Community 2.2

Mixed Brush Shrubland Community

The Mixed-Brush Shrubland Community (2.2) is the result of lack of fire, and/or proper brush management. It may or may not have been accompanied by improper grazing management, although improper grazing management can increase the rate of degradation. Oaks, Ashe’s juniper, and/or honey mesquite dominate the Mixed-Brush Shrubland Community (2.2), which has greater than 50 percent woody canopy cover. It is now essentially a dense shrubland with remnant grasses under the canopy and within interspaces. Once the brush canopy exceeds 50 percent, annual production for the understory is limited and is generally made up of unpalatable shrubs, grasses, and forbs within tree and shrub interspaces. Common understory shrubs are pricklypear, sumacs, and vines. Without fire and/or brush control, tree and shrub species will continue to increase until they exceed 70 percent canopy cover, and potentially reach almost 100 percent canopy cover. Few remnant midgrasses and opportunistic shortgrasses, annuals, and perennial forbs occupy the woody plant interspaces. Characteristic grasses are threeawns (Aristida spp.), buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides), sedges (Carex spp.), hairy grama, and fall witchgrass (Digitaria cognata). Texas wintergrass and annuals are found in and around tree/shrub cover. Grasses and forbs make up 40 percent or less of the annual herbage production. Common forbs include dotted gayfeather (Liatris punctata), western ragweed, sensitive-briar, Mexican sagewort (Artemisia ludoviciana ssp. mexicana), and croton (Croton spp.). At its most extreme, this community takes on a woodland appearance, large woody species with understory dominated by low production grasses and forbs that have low palatability and high shade tolerance. Excessive cattle grazing tends to create a different response and structure to the community than does excessive deer or goat grazing. Excessive cattle grazing tends to accelerate invasion of shrubs because it creates conditions where young shrubs increase in vigor and size while palatable grasses decrease in vigor and abundance. Excess deer or goat grazing tends to create a dominance of large trees by removing both young shrubs and the young growth that grow below the browse line on larger shrubs and trees. While large trees will continue to increase in size, they will have very little production below the browse line. The site becomes dominated by large trees with little forage available for livestock or wildlife. Large trees with little understory provide much less soil protection than do dense stands of grass. As soils erode, understory species have reduced potential to revegetate the site. The bare area under the browse line creates a situation that provides poor forage conditions and poor visual cover for wildlife. If irreversible soil damage has occurred, it may be possible to remove brush and seed the site to a grassland community. However, it is very difficult and expensive to restore the site to reference conditions due to the loss of organic matter, soil horizons, soil microbes, and soil structure necessary to maintain the reference community. The shrub canopy acts to intercept rainfall and increase evapotranspiration losses, creating a more xeric microclimate. Soil fauna and organic mulch are reduced, exposing more of the soil surface to erosion in interspaces. However, within the woody canopy, hydrologic processes stabilize and soil organic matter and mulch begin to increase and eventually stabilize under the shrub canopy. The Mixed-Brush Shrubland Community (2.2) provides good habitat cover for wildlife, but only limited forage or browse is available for livestock or wildlife. At this stage, highly intensive restoration practices are needed to return the shrubland to grassland. Alternatives for restoration include brush control and range planting, proper stocking, prescribed grazing, and prescribed burning following restoration to maintain the desired community.

Figure 12. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 300 | 720 | 1200 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 125 | 300 | 500 |

| Forb | 75 | 180 | 300 |

| Total | 500 | 1200 | 2000 |

Figure 13. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6023, Oak/Juniper/Mesquite Complex. Oak/Juniper/Mesquite complex having greater than twenty percent woody canopy dominated by juniper and mesquite..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 3 | 8 | 20 | 25 | 19 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Without fire (natural or human-caused) and/or brush control, woody density and canopy cover will increase in the Mixed-Brush/Midgrass Community until it converts into the Mixed-Brush Shrubland Community. Improper grazing and/or long-term drought (or other growing season stress) will accelerate this transition. Woody species canopy exceeding 50% indicate this transition has occurred. Improper grazing or other long-term growing season stress can increase the composition of shortgrasses and low-growing (or unpalatable) forbs in the herbaceous component. Even with proper grazing, in the absence of fire, the woody component will increase to the point that the herbaceous component will shift in composition toward shortgrasses and forbs suited to growing in shaded conditions with little available soil moisture. The driver for community shift 2.1A is lack of fire and/or brush control.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Brush management and/or fire can reduce the woody component to below the transition level of 50% brush canopy. Continued fire and/or brush management will be required to maintain woody density and canopy below 50%. If the herbaceous component has transitioned to shortgrasses and low forbs, proper grazing (combined with favorable moisture conditions) will be necessary to facilitate the shift of the understory component to the midgrass-dominated Mixed-Brush/Midgrass Plant Community. Range planting may accelerate the transition of the herbaceous community, particularly when combined with favorable growing conditions. The driver for community shift 2.2A is fire and/or brush control.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning |

State 3

Converted Land State

Community 3.1

Converted Land Community

The Converted Land Community (3.1) occurs when the site, either the Savannah State (1) or Shrubland State (2), is cleared and plowed for planting to cropland, hayland, native grasses, tame pasture, or use as non-agricultural land. The Converted State includes cropland, tame pasture, hayland, rangeland, and go-back land. The native component of the prairie is usually lost when seeding non-natives. Even when reseeding with natives, the ecological processes defining the past states of the site can be permanently changed. Common introduced species include Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), kleingrass (Panicum coloratum), and Old World bluestems (Bothriochloa spp.). Wheat, oats, forage sorghum, grain sorghum, cotton, and corn are the major crop species. Cropland, pastureland, and hayland are intensively managed with annual cultivation and/or frequent use of herbicides, pesticides, and commercial fertilizers to increase production. Both crop and pasturelands require weed and shrub control because seeds remain present on the site, either by remaining in the soil or being transported to the site. Converted sites require continual fertilization for crops or tame pasture (particularly Bermudagrass) to perform well. Without agronomic inputs, the site will eventually return to either the Savannah or Shrubland State. The site is considered go-back land during the period between active management for pasture or cropland and the return to a native state. NRCS Forage Suitability Group Descriptions describe adapted species, management, and production potentials on pasturelands and haylands. The Sandy Loam site is frequently converted to cropland or tame pasture sites because of its deep fertile soils, favorable soil/water/plant relationship, and level terrain. Small grains are the principal annual crop, and bermudagrass is the primary introduced pasture species in this area. The Sandy Loam site can be an extremely productive forage producing site with the application of optimum amounts of fertilizer. Refer to Forage Suitability Group Descriptions for specific management recommendations, estimated production potentials, and species adaptation.

Figure 14. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6104, Introduced Pasture Seeding. Grass species such as bermudagrass, kleingrass, old world bluestems and other introduced grassland species are planted..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

Community 3.2

Abandoned Land Community

The Abandoned Land Community (3.2) occurs when the Converted Land Community (3.1) is abandoned or mismanaged. Mismanagement can include poor crop or haying management. Pastureland can transition to the Abandoned Land Community when subjected to improper grazing management (typically long-term overgrazing). Heavily disturbed soils allowed to “Go Back” return to the Shrubland State. These sites may become an eastern red cedar brake over time. Long-term cropping can create changes in soil chemistry and structure that make restoration to the reference state very difficult and/or expensive. Return to native prairie communities in the Savannah State is more likely to be successful if soil chemistry, microorganisms, and structure are not heavily disturbed. Preservation of favorable soil microbes increases the likelihood of a return to reference conditions. Restoration to native prairie will require seedbed preparation and seeding of native species. Protocols and plant materials for restoring prairie communities is a developing portion of restoration science. Sites can be restored to the Savannah State in the short-term by seeding mixtures of commercially-available native grasses. With proper management (prescribed grazing, weed control, brush control) these sites can come close to the diversity and complexity of Tallgrass/Oak Savannah Community (1.1). It is unlikely that abandoned farmland will return to the Savannah State without active brush management because the rate of shrub increase will exceed the rate of recovery by desirable grass species. Without active restoration the site is not likely to return to reference conditions due to the introduction of introduced forbs and grasses. The native component of the prairie is usually lost when seeding non-natives. Even when reseeding with natives, the ecological processes defining the past states of the site can be permanently changed.

Figure 15. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX6105, Abandoned Land Community. Mix of perennial and annual weedy species mixed with native and invasive woody species with peak biomass production in April, May, and June and a lesser peak in September and October..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

Pathway 3.1A

Community 3.1 to 3.2

The Converted Land Community (3.1) will transition to the Abandoned Land Community (3.2) if improperly managed as cropland, hayland, or pastureland. Each of these types of converted land requires constant management input for maintenance or improvement. This includes inputs of tillage, weed management, brush control, fertilizer, and reseeding of annual crops. The driver of this transition is the lack of management inputs necessary to maintain cropland, hayland, or pastureland.

Pathway 3.2A

Community 3.2 to 3.1

The Abandoned Land Community (3.2) will transition to the Converted Land Community (3.1) with proper management inputs. The drivers for this transition are weed control, brush control, tillage, proper grazing management, and range or pasture planting.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Forage and Biomass Planting | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Shrubs make up a portion of the plant community in the Savannah State, hence woody propagules are present. Therefore, the Savannah State is always at risk for shrub dominance and the transition to the Shrubland State in the absence of fire. The driver for Transition T1A is lack of fire and/or brush control. The mean fire return interval in the Savannah State is 2-5 years. Even with proper grazing and favorable climate conditions, lack of fire for 10-20 years will allow woody species to increase in canopy to reach the 35% threshold level. Introduction of aggressive woody invader species (i.e. juniper or mesquite) increase the risk and accelerate the rate at which this transition state is likely to occur. This transition can occur from any community within the Savannah State, it is not dependant on degradation of the herbaceous community, but on the lack of some form of brush control. Improper grazing, prolonged drought, and a warming climate will provide a competitive advantage to shrubs which will accelerate this process. Tallgrasses will decrease to less than 5% species composition.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The transition (T1B) to the Converted State from either the Savannah State occurs when the prairie is plowed for planting to cropland or hayland. The size and density of brush in the Shrubland State will require heavy equipment and energy-intensive practices (i.e. rootplowing, raking, rollerchopping, or heavy disking) to prepare a seedbed. The threshold for this transition is the plowing of the prairie soil and removal of the prairie plant community. The Converted State includes cropland, tame pasture, and “go-back land.” The site is considered “go-back land” during the period between cessation of active cropping, fertilization, and weed control and the return to the “native” states. Agronomic practices are used to convert rangeland to the Converted State and to make changes between the communities in the Converted State. The driver for these transitions is management’s decision to farm the site.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Restoration of the Shrubland State to the Savannah State requires substantial energy input. Mechanical or herbicidal brush control treatments can be used to remove woody species. A long-term prescribed fire program may sufficiently reduce brush density to a level below the threshold of the Savannah State, particularly if the woody component is dominated by species that are not fire sprouters. Brush control in combination with prescribed fire, proper grazing, and favorable growing conditions may be the most economical means of creating and maintaining the desired plant community. If remnant populations of tallgrasses, midgrasses, and desirable forbs are not present at sufficient levels, range planting will be necessary to restore a desirable herbaceous plant community. The driver for Restoration Pathway R2A is fire and/or brush control combined with natural restoration of the herbaceous community or active management of the herbaceous restoration process (range seeding). Restoration may require aggressive treatment of invader species.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

The transition (T2A) to the Converted State from the Shrubland State occurs when the prairie is plowed for planting to cropland or hayland. The size and density of brush in the Shrubland State will require heavy equipment and energy-intensive practices (i.e. rootplowing, raking, rollerchopping, or heavy disking) to prepare a seedbed. The threshold for this transition is the plowing of the prairie soil and removal of the prairie plant community. The Converted State includes cropland, tame pasture, and “go-back land.” The site is considered “go-back land” during the period between cessation of active cropping, fertilization, and weed control and the return to the “native” states. Agronomic practices are used to convert rangeland to the Converted State and to make changes between the communities in the Converted State. The driver for these transitions is management’s decision to farm the site.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 1

Restoration from the Converted State can occur in the short term through active restoration or over the long-term due to cessation of agronomic practices. Cropland and tame pasture require repeated and continual inputs of fertilizer and weed control to maintain the Converted State. If the soil chemistry and structure have not been overly disturbed (which is most likely to occur with tame pasture and cropland) the site can be restored to the Savannah State. Preservation of favorable soil microbes increases the likelihood of a return to reference conditions. Without continued disturbance from agriculture the site can eventually return to the Savannah State. Converted sites can be returned to the Savannah State through active restoration, including seedbed preparation and seeding of native grass and forb species. Protocols and plant materials for restoring prairie communities is a developing part of restoration science. The driver for both of these restoration pathways is the cessation of agricultural disturbances.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Range Planting | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Restoration pathway R3B

State 3 to 2

Restoration from the Converted State can occur in the short term through active restoration or over the long-term due to cessation of agronomic practices. Cropland and tame pasture require repeated and continual inputs of fertilizer and weed control to maintain the Converted State. Heavily disturbed soils are more likely to return to the Shrubland State. Without continued disturbance from agriculture the site can eventually return to the Shrubland State. Protocols and plant materials for restoring prairie communities is a developing part of restoration science. The driver for both of these restoration pathways is the cessation of agricultural disturbances.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Range Planting |

Additional community tables

Table 9. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Tallgrass | 1750–3250 | ||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | 1750–3250 | – | ||

| 2 | Tallgrasses | 350–650 | ||||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 100–650 | – | ||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 100–325 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 100–325 | – | ||

| 3 | Mid/Shortgrasses | 525–975 | ||||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 0–800 | – | ||

| hairy grama | BOHI2 | Bouteloua hirsuta | 0–650 | – | ||

| silver beardgrass | BOLAT | Bothriochloa laguroides ssp. torreyana | 0–650 | – | ||

| cane bluestem | BOBA3 | Bothriochloa barbinodis | 0–650 | – | ||

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | 0–650 | – | ||

| composite dropseed | SPCOC2 | Sporobolus compositus var. compositus | 0–650 | – | ||

| Drummond's dropseed | SPCOD3 | Sporobolus compositus var. drummondii | 0–650 | – | ||

| sand dropseed | SPCR | Sporobolus cryptandrus | 0–650 | – | ||

| Texas wintergrass | NALE3 | Nassella leucotricha | 0–500 | – | ||

| vine mesquite | PAOB | Panicum obtusum | 0–500 | – | ||

| cylinder jointtail grass | COCY | Coelorachis cylindrica | 0–500 | – | ||

| Scribner's rosette grass | DIOLS | Dichanthelium oligosanthes var. scribnerianum | 0–450 | – | ||

| plains lovegrass | ERIN | Eragrostis intermedia | 0–400 | – | ||

| mourning lovegrass | ERLU | Eragrostis lugens | 0–400 | – | ||

| sand lovegrass | ERTR3 | Eragrostis trichodes | 0–400 | – | ||

| purpletop tridens | TRFL2 | Tridens flavus | 0–400 | – | ||

| 4 | Mid/Shortgrasses | 175–325 | ||||

| buffalograss | BODA2 | Bouteloua dactyloides | 0–325 | – | ||

| Arizona cottontop | DICA8 | Digitaria californica | 0–325 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 5 | Forbs | 350–650 | ||||

| Engelmann's daisy | ENPE4 | Engelmannia peristenia | 0–550 | – | ||

| snow on the mountain | EUMA8 | Euphorbia marginata | 0–500 | – | ||

| beeblossom | GAURA | Gaura | 0–500 | – | ||

| Dakota mock vervain | GLBIB | Glandularia bipinnatifida var. bipinnatifida | 0–500 | – | ||

| coastal indigo | INMI | Indigofera miniata | 0–500 | – | ||

| lespedeza | LESPE | Lespedeza | 0–500 | – | ||

| dotted blazing star | LIPU | Liatris punctata | 0–500 | – | ||

| sensitive plant | MIMOS | Mimosa | 0–500 | – | ||

| Nuttall's sensitive-briar | MINU6 | Mimosa nuttallii | 0–500 | – | ||

| wild bergamot | MOFI | Monarda fistulosa | 0–500 | – | ||

| yellow puff | NELU2 | Neptunia lutea | 0–500 | – | ||

| scurfpea | PSORA2 | Psoralidium | 0–500 | – | ||

| fuzzybean | STROP | Strophostyles | 0–500 | – | ||

| prairie clover | DALEA | Dalea | 0–500 | – | ||

| bundleflower | DESMA | Desmanthus | 0–500 | – | ||

| ticktrefoil | DESMO | Desmodium | 0–500 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 6 | Shrubs/Vines/Trees | 350–650 | ||||

| blackjack oak | QUMA3 | Quercus marilandica | 100–650 | – | ||

| post oak | QUST | Quercus stellata | 100–650 | – | ||

| hackberry | CELTI | Celtis | 0–400 | – | ||

| plum | PRUNU | Prunus | 0–400 | – | ||

| elm | ULMUS | Ulmus | 0–250 | – | ||

| Carolina coralbead | COCA | Cocculus carolinus | 0–200 | – | ||

| prairie sumac | RHLA3 | Rhus lanceolata | 0–200 | – | ||

| skunkbush sumac | RHTR | Rhus trilobata | 0–200 | – | ||

| saw greenbrier | SMBO2 | Smilax bona-nox | 0–150 | – | ||

| Vine, woody | 2VW | Vine, woody | 0–150 | – | ||

| yucca | YUCCA | Yucca | 0–150 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Deer, dove and quail inhabit this site. A wide variety of woody and herbaceous vegetation affords food and cover for this wildlife.

Plant Preference by Animal Kind:

This rating system provides general guidance as to animal preference for plant species. It also indicates possible competition between kinds of herbivores for various plants. Grazing preference changes from time to time, especially between seasons, and between animal kinds and classes. Grazing preference does not necessarily reflect the ecological status of the plant within the plant community.

Preferred (P) – Percentage of plant in animal diet is greater than it occurs on the land

Desirable (D) – Percentage of plant in animal diet is similar to the percentage composition on the land

Undesirable (U) – Percentage of plant in animal diet is less than it occurs on the land

Not Consumed (N) – Plant would not be eaten under normal conditions; only consumed when other forages not available.

Used, but degree of utilization unknown (X) – Percentage of plant in animal diet is unknown

Toxic (T) – Rare occurrence in diet and, if consumed in any tangible amounts results in death or severe illness in animal

Hydrological functions

The Sandy Loam ecological site occurs on nearly level to moderately sloping sandy loam soils. The soils are moderately well-drained. They have moderately slow permeability and internal drainage. Surface runoff is moderate to rapid. Wind and water erosion can occur where the site is not protected by vegetation. Soil depth and texture allow maximum penetration of grass roots.

In the Savannah State grassland vegetation intercepts and utilizes much of the rainfall. In the Shrubland State shrub canopy intercepts much of the rainfall, but that which strikes the ground may cause erosion if soils are bare. Evaporation losses are higher in the Shrubland State, which when combined with interception losses, results in less moisture reaching the rooting zone.

Litter and soil moves little in the Savannah State. However, standing plant cover, duff and soil organic matter decrease as site transitions from the Savannah State to the Shrubland State.

Recreational uses

Recreational uses include photography, hiking, camping, horseback riding, bird watching, and off-road vehicle use. Profitable hunting enterprises have been established on this site for quail, deer, dove, and turkey.

Wood products

Honey mesquite, eastern redcedar, and some oak are used for posts, firewood, charcoal, and other specialty wood products.

Other products

Jams and jellies are made from many fruit bearing species. Seeds are harvested from many plants for commercial sale. Many grasses and forbs are harvested by the dried-plant industry for sale in dried flower arrangements. Honeybees are utilized to harvest honey from many flowering plants, such as honey mesquite.

Other information

None.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented was derived from the revised Sandy Loam Range Site, NRCS clipping data, literature, field observations, and personal contacts with range-trained personnel.

Other references

Reviewers:

Lem Creswell, RMS, NRCS, Weatherford, Texas

Justin Clary, RMS, NRCS, Temple, Texas

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to the following personnel for assistance and/or guidance with the development of this ESD: Justin Clary, NRCS, Temple, TX; Mark Moseley, NRCS, San Antonio, TX; Ricky Marks, NRCS, Brownwood, TX; Rhett Johnson, Granbury, TX; Michael and Susannah Wisenbaker, Dallas, TX; Rancho Hielo Brazos, Glen Rose, TX; and Dr. Ricky Fain, Chalk Mountain, TX.

Other References:

1. Archer, S. 1994. Woody plant encroachment into southwestern grasslands and savannas: rates, patterns and proximate causes. In: Ecological implications of livestock herbivory in the West, pp. 13-68. Edited by M. Vavra, W. Laycock, R. Pieper. Society for Range Management Publication, Denver, CO.

2. Archer, S. and F.E. Smeins. 1991. Ecosystem-level Processes. Chapter 5 in: Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heitschmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

3. Bestelmeyer, B.T., J.R. Brown, K.M. Havstad, R. Alexander, G. Chavez, and J.E. Herrick. 2003. Development and use of state-and-transition models for rangelands. J. Range Manage. 56(2): 114-126.

4. Brown, J.R. and S. Archer. 1999. Shrub invasion of grassland: recruitment is continuous and not regulated by herbaceous biomass or density. Ecology 80(7): 2385-2396.

5. Foster, J.H. 1917. Pre-settlement fire frequency regions of the United States: a first approximation. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings No. 20.

6. Gould, F.W. 1975. The Grasses of Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX. 653p.

7. Hamilton, W. and D. Ueckert. 2005. Rangeland Woody Plant Control: Past, Present, and Future. Chapter 1 in: Brush Management: Past, Present, and Future. pp. 3-16. Texas A&M University Press.

8. Scifres, C.J. and W.T. Hamilton. 1993. Prescribed Burning for Brush Management: The South Texas Example. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX. 245 p.

9. Smeins, F., S. Fuhlendorf, and C. Taylor, Jr. 1997. Environmental and Land Use Changes: A Long Term Perspective. Chapter 1 in: Juniper Symposium 1997, pp. 1-21. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station.

10. Stringham, T.K., W.C. Krueger, and P.L. Shaver. 2001. State and transition modeling: and ecological process approach. J. Range Manage. 56(2):106-113.

11. Texas Agriculture Experiment Station. 2007. Benny Simpson’s Texas Native Trees (http://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/ornamentals/natives/).

12. Texas A&M Research and Extension Center. 2000. Native Plants of South Texas (http://uvalde.tamu.edu/herbarium/index.html).

13. Thurow, T.L. 1991. Hydrology and Erosion. Chapter 6 in: Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heitschmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

14. USDA/NRCS Soil Survey Manuals for appropriate counties for MLRA.

15. USDA, NRCS. 1997. National Range and Pasture Handbook.

16. USDA, NRCS. 2007. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov). National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA.

17. Vines, R.A. 1984. Trees of Central Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

18. Vines, R.A. 1977. Trees of Eastern Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX. 538 p.

19. Wright, H.A. and A.W. Bailey. 1982. Fire Ecology: United States and Southern Canada. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Contributors

Jack Alexander, Synergy Resource Solutions Inc, Belgrade, Montana And Dan Caudle, Weatherford, Texas

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Lem Creswell, RMS, NRCS, Weatherford, Texas |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | 817-596-2865 |

| Date | 08/05/2008 |

| Approved by | Mark Moseley, RMS, NRCS, San Antonio, Texas |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Water flow patterns are common and follow old stream meanders. Deposition or erosion is uncommon for normal rainfall but may occur during intense rainfall events. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

Pedestals or terracettes would have been uncommon for this site. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

None. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

Some gullies may be present on side drains into perennial and intermittent streams. Gullies should be vegetated and stable. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Under normal rainfall, little litter movement should be expected; however, litter of all sizes may move long distances. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil surface under HCPC is resistant to erosion. Stability class range is expected to be 5-6. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

0-4 inches brown loam, moderate fine granular structure, surface crusty when dry, hard, friable, many fine roots, slightly alkaline, clear smooth boundary. SOM is 1-4%. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

The savannah of tallgrasses, midgrasses, and forbs having adequate litter and little bare ground can provide for maximum infiltration and little runoff under normal rainfall events. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

No evidence of compaction. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm-season tallgrasses >>Sub-dominant:

Warm-season midgrasses > Trees >Other:

Cool-season midgrasses > Forbs > Shrubs/VinesAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Grasses due to their growth habit will exhibit some mortality and decadence, though very slight. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Litter is primarily herbaceous. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

3500 to 6500 pounds per acre. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Ashe juniper, honey mesquite, pricklypear, bermudagrass, johnsongrass, and King Ranch bluestem. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All perennial plants should be capable of reproducing, except during periods of prolonged drought conditions, heavy herbivory, and wildfires.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.