Ecological dynamics

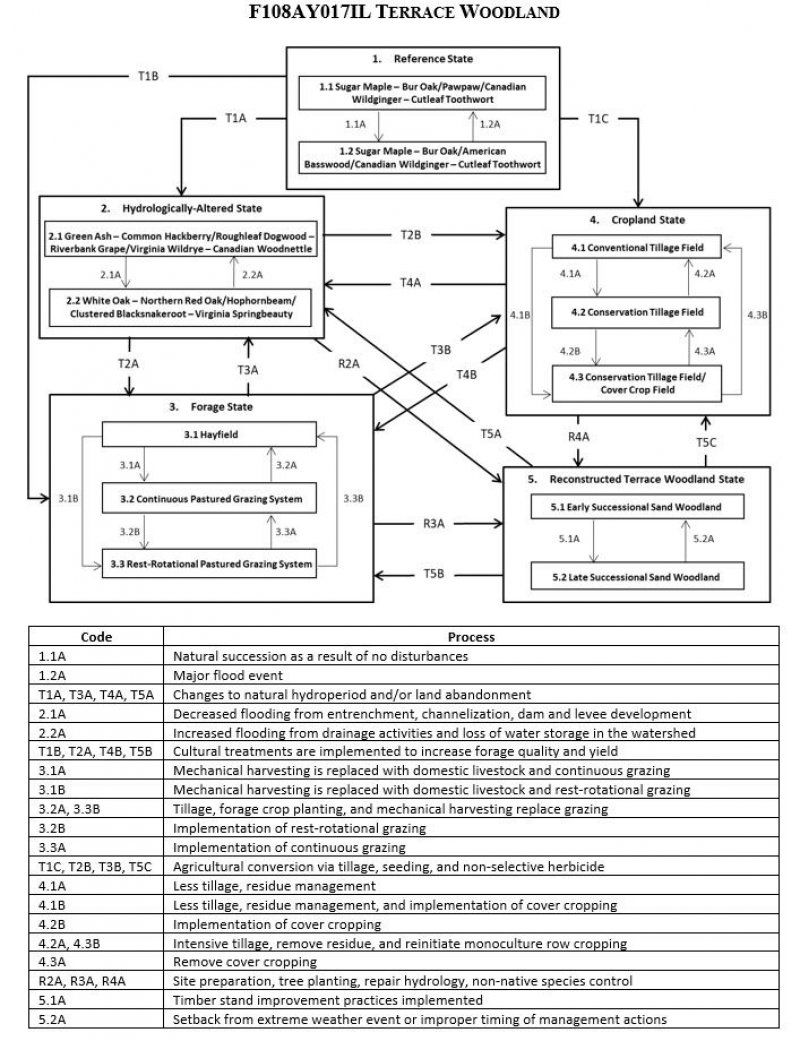

The information in this Ecological Site Description, including the state-and-transition model (STM), was developed based on historical data, current field data, professional experience, and a review of the scientific literature. As a result, all possible scenarios or plant species may not be included. Key indicator plant species, disturbances, and ecological processes are described to inform land management decisions.

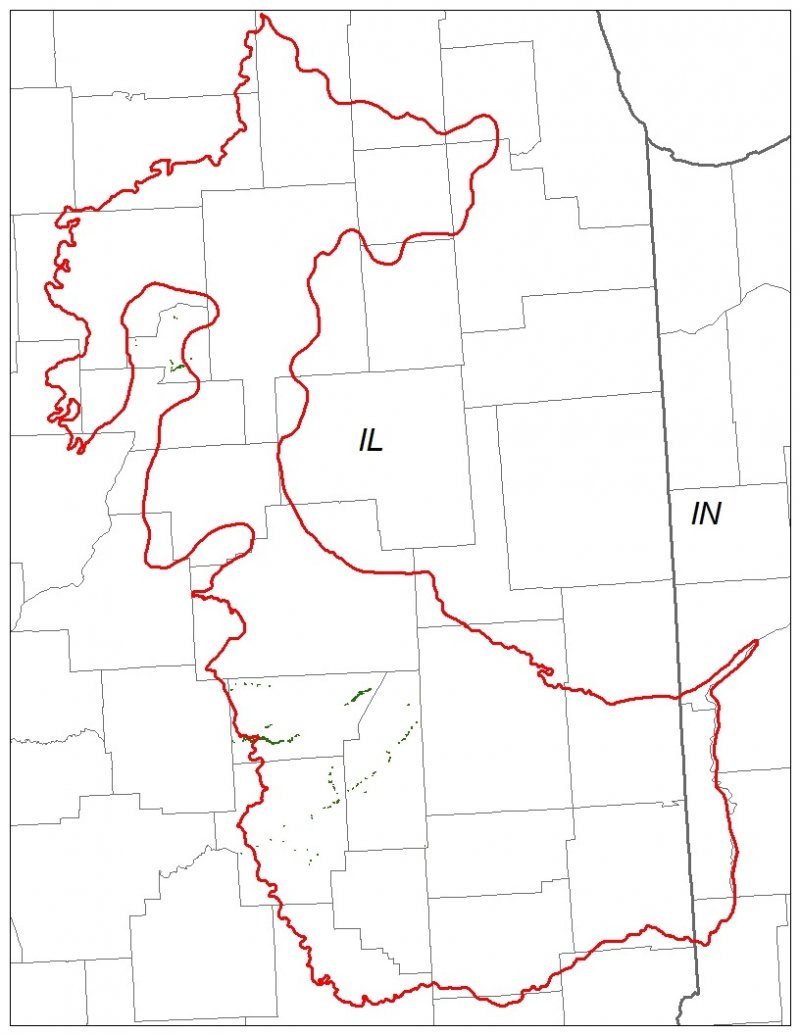

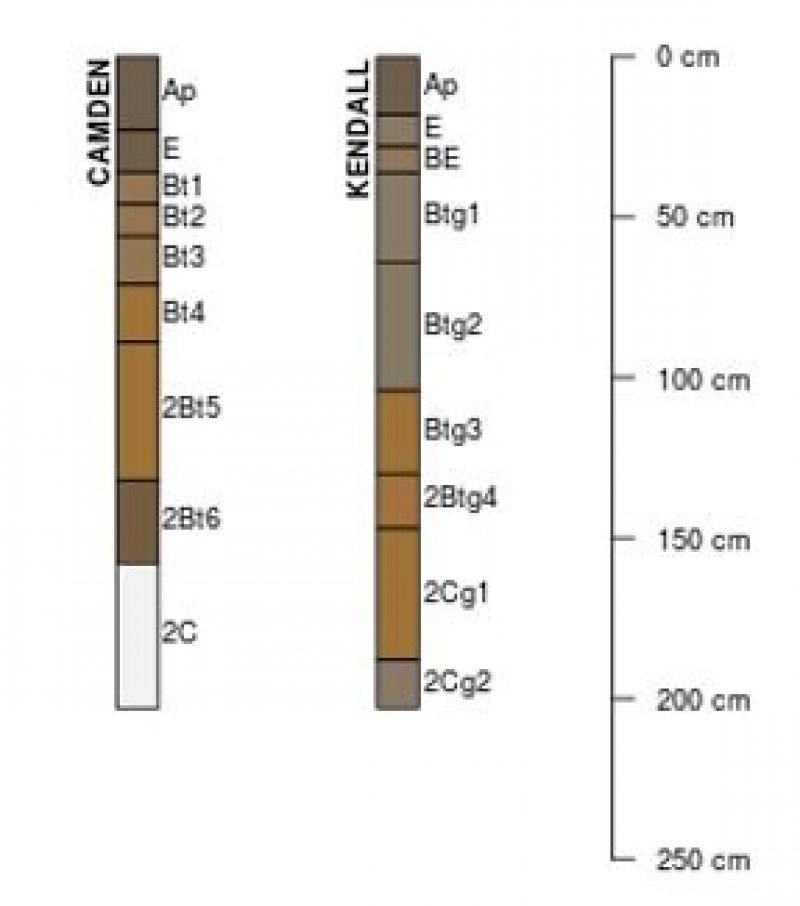

The MLRA lies within the tallgrass prairie ecosystem of the Midwest. The heterogeneous topography of the area results in variable microclimates and fuel matrices that in turn support prairies, savannas, and forests. Terrace Woodlands form an aspect of this vegetative continuum. This ecological site occurs on rarely-flooded stream terraces on somewhat poorly to well-drained soils. Species characteristic of this ecological site consist of highly intermixed upland and lowland woody and herbaceous vegetation.

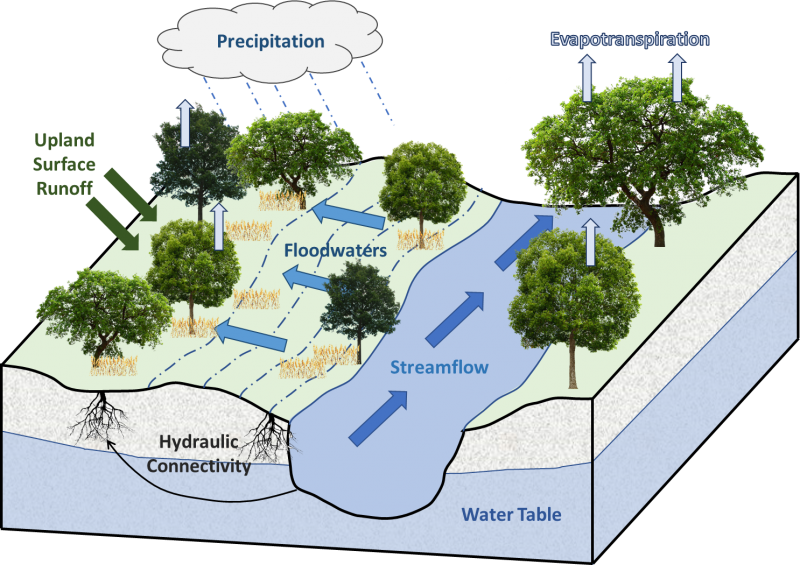

Flooding is the dominant disturbance factor in Terrace Woodlands, and storm damage and pests are secondary disturbances. Seasonal flooding occurs approximately every 20 to 100 years, and flooding can persist for up to two days at a time. Damage to trees from wind storms can vary from minor, patchy effects of individual trees to stand effects that temporarily affect community structure and species richness and diversity (Irland 2000; Peterson 2000). Trees are susceptible to a variety of pests (e.g., insects, fungi, cankers, wilts), therefore periodic insect and disease outbreaks play an important role in local canopy structure.

Today, many Terrace Woodlands have been reduced as a result of conversion to pasture. A few sites have been cleared and drained for agricultural production. Remnant sites have been degraded due to significant changes to the natural hydrologic regime and diminished water quality in the watershed. The state-and-transition model that follows provides a detailed description of each state, community phase, pathway, and transition. This model is based on available experimental research, field observations, literature reviews, professional consensus, and interpretations.

State 1

Reference State

The reference plant community is categorized as a floodplain woodland community, dominated by both upland and lowland woody and herbaceous vegetation. The two community phases within the reference state are dependent on rare flooding. The amount and duration of flooding alters species composition, cover, and extent. Periodic pest outbreaks and wind storms have more localized impacts in the reference phases, but do contribute to overall species composition, diversity, cover, and productivity.

Community 1.1

Sugar Maple - Bur Oak/Pawpaw/Canadian Wildginger - Cutleaf Toothwort

Sites in this reference community phase are a closed canopy woodland (60 to 80 percent cover), defined by a mixture of hardwood trees. Sugar maple, bur oak, and American elm are common trees on the site, but other species present include hackberry, green ash, white oak, northern red oak, and black walnut(Juglans nigra L.). Trees are very large (>33-inch DBH) and range in height from 30 to over 80 feet tall (LANDFIRE 2009). Pawpaw is a dominant shrub in the plant community, and Canadian wildginger and cutleaf toothwort are common herbaceous species. Other ground layer species can include ramp (Allium tricoccum Aiton), bloody butcher (Trillium recurvatum Beck), Virginia waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginanum L.), and Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica (L.) Pers. Ex Link) (INHS 2012). Rare flooding will maintain this phase, but a prolonged period of no disturbances will transition the site to community phase 1.2.

Community 1.2

Sugar Maple - Bur Oak/American Basswood/Canadian Wildginger - Cutleaf Toothwort

This reference community phase represents a late-sere plant community. Tree species diversity is still high, but the overstory cover shifts to a closed canopy forest (80 to 100 percent cover). As the community moves into an old-growth phase, the subcanopy overtops the shrub layer. Continued lack of disturbances will maintain this phase, but a major flood event will shift the site back to community phase 1.1.

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Natural succession as a result of no disturbances.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Major flood event.

State 2

Hydrologically-Altered State

Agricultural tile drainage, stream channelization, habitat fragmentation, agricultural land development, and levee construction in hydrologically-connected waters have drastically changed the natural hydrologic regime of Terrace Woodlands (INHS 2012). In addition, increased amounts of precipitation and intensity have amplified flooding events (Pryor et al. 2014). This has resulted in a type conversion from the species-rich forest to either a wetter or drier plant community. In addition, exotic species have encroached and continuously spread, reducing native diversity and ecosystem stability.

Community 2.1

Green Ash - Common Hackberry/Roughleaf Dogwood - Riverbank Grape/Virginia Wildrye - Canadian Woodnettle

This community represents a transition in plant community composition as a result of an increased flooding regime. Upland drainage activities and loss of water storage across the watershed are some types of anthropogenic alterations that can increase flooding of this site. As a result, the community develops into more of a Silty Floodplain Forest (F108AY019IL) ecological site dominated by wet and wet-mesic woody and herbaceous plants.

Community 2.2

White Oak - Northern Red Oak/Hophornbeam/Clustered Blacksnakeroot - Virginia Springbeauty

This community phase represents significant decreases in the flooding regime from activities such as stream entrenchment, channelization, levee formation, and dam development. The resulting plant community develops into an upland forest type, such as the Loess Upland Forest (F108AY011IL) or Outwash Forest (F108AY015IL) ecological site. Non-native invasive species are likely to be encountered, including honeysuckle (Lonicera L.), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora L.), and garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata(M. Bieb.) Cavara & Grande).

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Decreased flooding from entrenchment, channelization, dam and levee development.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Increased flooding from stream entrenchment, channelization, and/or levee and dam development.

State 3

Forage State

The forage state occurs when the reference state is converted to a farming system that emphasizes domestic livestock production known as grassland agriculture. Selective tree removal, periodic cultural treatments (e.g., clipping, drainage, soil amendment applications, planting new species and/or cultivars, mechanical harvesting) and grazing by domesticated livestock transition and maintain this state (USDA-NRCS 2003). Early settlers seeded non-native species, such as smooth brome (Bromus inermis Leyss.) and Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.), to help extend the grazing season. Over time, as lands were continuously harvested or grazed by herds of cattle, the non-native species were able to spread and expand across the landscape, reducing the native species diversity and ecological function.

Community 3.1

Hayfield

Sites in this community phase consist of forage plants that are planted and mechanically harvested. Mechanical harvesting removes much of the aboveground biomass and nutrients that feed the soil microorganisms (Franzluebbers et al. 2000; USDA-NRCS 2003). As a result, soil biology is reduced leading to decreases in nutrient uptake by plants, soil organic matter, and soil aggregation. Frequent biomass removal can also reduce the site's carbon sequestration capacity (Skinner 2008).

Community 3.2

Continuous Pastured Grazing System

This community phase is characterized by continuous grazing where domestic livestock graze a pasture for the entire season. Depending on stocking density, this can result in lower forage quality and productivity, weed invasions, and uneven pasture use. Continuous grazing can also increase the amount of bare ground and erosion and reduce soil organic matter, cation exchange capacity, water-holding capacity, and nutrient availability and retention (Bharati et al. 2002; Leake et al. 2004; Teague et al. 2011). Smooth brome, Kentucky bluegrass, and white clover (Trifolium repens L.) are common pasture species used in this phase. Their tolerance to continuous grazing has allowed these species to dominate, sometimes completely excluding the native vegetation.

Community 3.3

Rest-Rotation Pastured Grazing System

This community phase is characterized by rotational grazing where the pasture has been subdivided into several smaller paddocks. Through the development of a grazing plan, livestock utilize one or a few paddocks, while the remaining area is rested allowing plants to restore vigor and energy reserves, deepen root systems, develop seeds, as well as allow seedling establishment (Undersander et al. 2002; USDA-NRCS 2003). Rest-rotation pastured grazing systems include deferred rotation, rest rotation, high intensity – low frequency, and short duration methods. Vegetation is generally more diverse and can include orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.), timothy (Phleum pretense L.), red clover (Trifolium pratense L.), and alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). The addition of native prairie species can further bolster plant diversity and, in turn, soil function. This community phase promotes numerous ecosystem benefits including increasing biodiversity, preventing soil erosion, maintaining and enhancing soil quality, sequestering atmospheric carbon, and improving water yield and quality (USDA-NRCS 2003).

Pathway 3.1A

Community 3.1 to 3.2

Mechanical harvesting is replaced with domestic livestock utilizing continuous grazing.

Pathway 3.1B

Community 3.1 to 3.3

Mechanical harvesting is replaced with domestic livestock utilizing rotational grazing.

Pathway 3.2A

Community 3.2 to 3.1

Domestic livestock are removed, and mechanical harvesting is implemented.

Pathway 3.2B

Community 3.2 to 3.3

Rotational grazing replaces continuous grazing.

Pathway 3.3B

Community 3.3 to 3.1

Domestic livestock are removed, and mechanical harvesting is implemented.

Pathway 3.3A

Community 3.3 to 3.2

Continuous grazing replaces rotational grazing.

State 4

Cropland State

The continuous use of tillage, row-crop planting, and chemicals (i.e., herbicides, fertilizers, etc.) has effectively eliminated the reference community and many of its natural ecological functions in favor of crop production. Corn and soybeans are the dominant crops for the site, and oats (Avena L.) and alfalfa (Medicago sativaL.) may be rotated periodically. These areas are likely to remain in crop production for the foreseeable future.

Community 4.1

Conventional Tillage Field

Sites in this community phase typically consist of monoculture row-cropping maintained by conventional tillage practices. They are cropped in either continuous corn or corn-soybean rotations. The frequent use of deep tillage, low crop diversity, and bare soil conditions during the non-growing season negatively impacts soil health. Under these practices, soil aggregation is reduced or destroyed, soil organic matter is reduced, erosion and runoff are increased, and infiltration is decreased, which can ultimately lead to undesirable changes in the hydrology of the watershed (Tomer et al. 2005).

Community 4.2

Conservation Tillage Field

This community phase is characterized by rotational crop production that utilizes various conservation tillage methods to promote soil health and reduce erosion. Conservation tillage methods include strip-till, ridge-till, vertical-till, or no-till planting systems. Strip-till keeps seedbed preparation to narrow bands less than one-third the width of the row where crop residue and soil consolidation are left undisturbed in-between seedbed areas. Strip-till planting may be completed in the fall and nutrient application either occurs simultaneously or at the time of planting. Ridge-till uses specialized equipment to create ridges in the seedbed and vegetative residue is left on the surface in between the ridges. Weeds are controlled with herbicides and/or cultivation, seedbed ridges are rebuilt during cultivation, and soils are left undisturbed from harvest to planting. Vertical-till systems employ machinery that lightly tills the soil and cuts up crop residue, mixing some of the residue into the top few inches of the soil while leaving a large portion on the surface. No-till management is the most conservative, disturbing soils only at the time of planting and fertilizer application. Compared to conventional tillage systems, conservation tillage methods can improve soil ecosystem function by reducing soil erosion, increasing organic matter and water availability, improving water quality, and reducing soil compaction.

Community 4.3

Conservation Tillage Field/Alternative Crop Field

This community phase applies conservation tillage methods as described above as well as adds cover crop practices. Cover crops typically include nitrogen-fixing species (e.g., legumes), small grains (e.g., rye, wheat, oats), or forage covers (e.g., turnips, radishes, rapeseed). The addition of cover crops not only adds plant diversity but also promotes soil health by reducing soil erosion, limiting nitrogen leaching, suppressing weeds, increasing soil organic matter, and improving the overall soil ecosystem. In the case of small grain cover crops, surface cover and water infiltration are increased, while forage covers can be used to graze livestock or support local wildlife. Of the three community phases for this state, this phase promotes the greatest soil sustainability and improves ecological functioning within a cropland system.

Pathway 4.1A

Community 4.1 to 4.2

Tillage operations are greatly reduced, crop rotation occurs on a regular interval, and crop residue remains on the soil surface.

Pathway 4.1B

Community 4.1 to 4.3

Tillage operations are greatly reduced or eliminated, crop rotation occurs on a regular interval, crop residue remains on the soil surface, and cover crops are planted following crop harvest.

Pathway 4.2A

Community 4.2 to 4.1

Intensive tillage is utilized, and monoculture row-cropping is established.

Pathway 4.2B

Community 4.2 to 4.3

Cover crops are implemented to minimize soil erosion.

Pathway 4.3B

Community 4.3 to 4.1

Intensive tillage is utilized, cover crop practices are abandoned, monoculture row-cropping is established, and crop rotation is reduced or eliminated.

Pathway 4.3A

Community 4.3 to 4.2

Cover crop practices are abandoned.

State 5

Reconstructed Terrace Woodland State

The combination of natural and anthropogenic disturbances occurring today has resulted in numerous ecosystem health issues, and restoration back to the historic reference state may not be possible. Many natural woodland communities are being stressed by non-native diseases and pests, habitat fragmentation, permanent changes in hydrologic regimes, and overabundant deer populations on top of naturally-occurring disturbances (severe weather and native pests) (IFDC 2018). However, these habitats provide multiple ecosystem services including carbon sequestration; clean air and water; soil conservation; biodiversity support; wildlife habitat; as well as a variety of cultural activities (e.g., hiking, hunting) (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005; IFDC 2018). Therefore, conservation of these communities should still be pursued. Habitat reconstructions are an important tool for repairing natural ecological functioning and providing habitat protection for numerous species of Terrace Woodlands. Therefore, ecological restoration should aim to aid the recovery of degraded, damaged, or destroyed ecosystems. A successful restoration will have the ability to structurally and functionally sustain itself, demonstrate resilience to the ranges of stress and disturbance, and create and maintain positive biotic and abiotic interactions (SER 2002). The reconstructed terrace woodlands state is the result of a long-term commitment involving a multi-step, adaptive management process.

Community 5.1

Early Successional Reconstructed Woodland

This community phase represents the early community assembly from woodland reconstruction. It is highly dependent on the current condition of the site based on past and current land management actions, invasive species, and proximity to land populated with non-native pests and diseases. Therefore, no two sites will have the same early successional composition. Technical forestry assistance should be sought to develop suitable conservation management plans.

Community 5.2

Late Successional Reconstructed Woodland

Appropriately timed management practices (e.g., forest stand improvement, continuing integrated pest management) applied to the early successional community phase can help increase the stand maturity, pushing the site into a late successional community phase over time. A late successional reconstructed forest will have an uneven-aged, closed canopy and a well-developed understory.

Pathway 5.1A

Community 5.1 to 5.2

Application of stand improvement practices in line with a developed management plan.

Pathway 5.2A

Community 5.2 to 5.1

Reconstruction experiences a setback from extreme weather event or improper timing of management actions.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Altered hydrology throughout the watershed transitions the site to the hydrologically-altered state (2).

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Woody species removal and cultural treatments to enhance forage quality and yield transition the site to the forage state (3).

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

Woody species removal, tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition the site to the cropland state (4).

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Woody species removal and cultural treatments to enhance forage quality and yield transition the site to the forage state (3).

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

Woody species removal, tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition the site to the cropland state (4).

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 5

Site preparation, tree planting, timer stand improvement, non-native species control, and water control structures installed to improve and regulate hydrology transition this site to the reconstructed terrace woodland state (5).

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

Land is abandoned and left fallow; natural succession by opportunistic species transition this site the hydrologically-altered state (2).

Transition T3B

State 3 to 4

Tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition the site to the cropland state (4).

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 5

Site preparation, tree planting, timber stand improvement, non-native species control, and water control structures installed to improve and regulate hydrology transition this site to the reconstructed terrace woodland state (5).

Transition T4A

State 4 to 2

Land abandonment transitions the site to the hydrologically-altered state (2).

Transition T4B

State 4 to 3

Cultural treatments to enhance forage quality and yield transition the site to the forage state (3).

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 5

Site preparation, tree planting, timber stand improvement, non-native species control, and water control structures installed to improve and regulate hydrology transition this site to the reconstructed terrace woodland state (5).

Transition T5A

State 5 to 2

Removal of water control structures and unmanaged invasive species populations transition this site to the hydrologically-altered state (2).

Transition T5B

State 5 to 3

Tree removal and cultural treatments to enhance forage quality and yield transition the site to the forage state (3).

Transition T5C

State 5 to 4

Tree removal, tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition this site to the cropland state (4).