Ecological dynamics

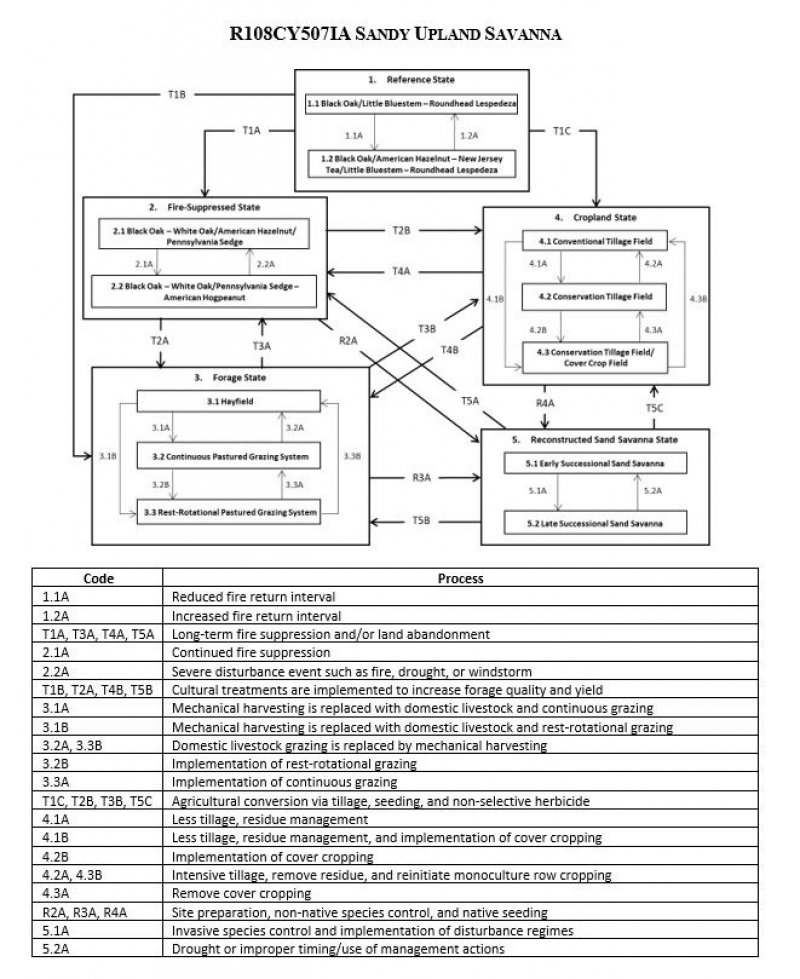

The information in this Ecological Site Description, including the state-and-transition model (STM), was developed based on historical data, current field data, professional experience, and a review of the scientific literature. As a result, all possible scenarios or plant species may not be included. Key indicator plant species, disturbances, and ecological processes are described to inform land management decisions.

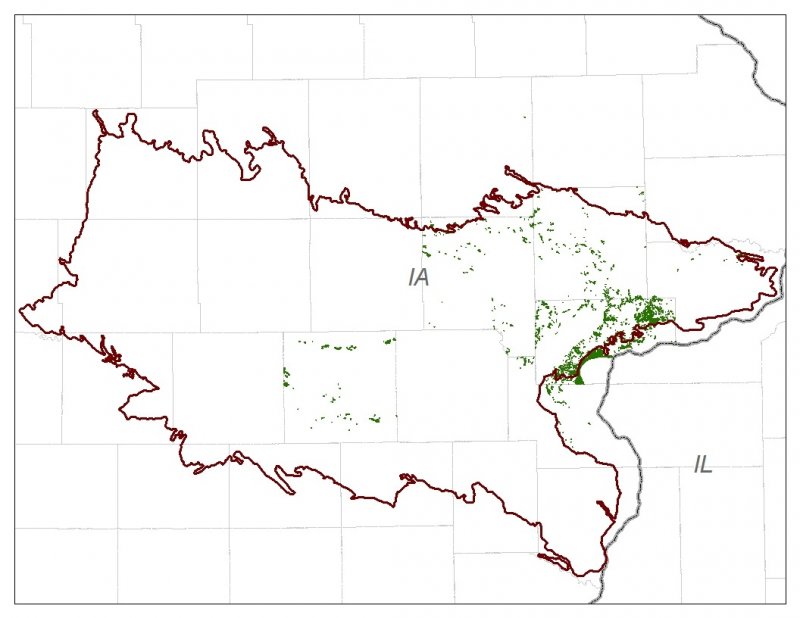

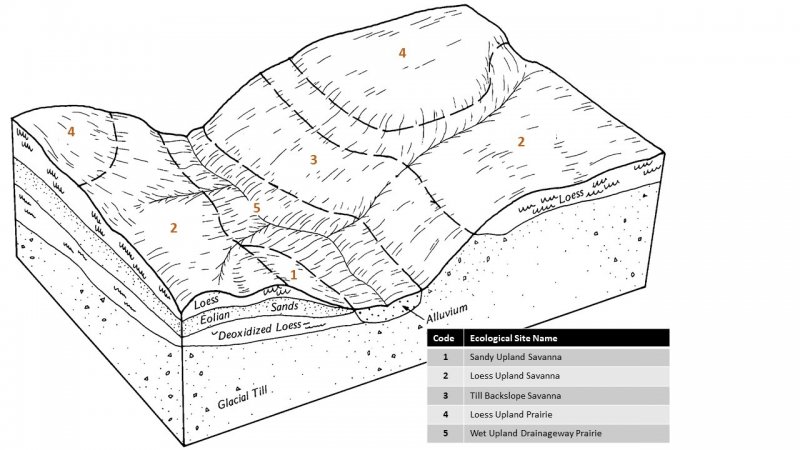

The MLRA lies within the transition zone between the eastern deciduous forests and the tallgrass prairies. The heterogeneous topography of the area results in variable microclimates and fuel matrices that in turn are able to support prairies, savannas, woodlands, and forests. Sandy Upland Savannas form an aspect of this vegetative continuum. This ecological site occurs on upland hillslopes and high stream terraces on well-drained soils. Species characteristic of this ecological site consist of herbaceous vegetation with an open canopy of deciduous trees.

Fire and grazing are critical disturbance factors that maintain Sandy Upland Savannas. Fire typically consisted of low-intensity surface fires occurring annually or near annually (LANDFIRE 2009). Ignition sources included summertime lightning strikes from convective storms and bimodal, human ignitions during the spring and fall seasons. Native Americans regularly set fires to improve sight lines for hunting, driving large game, improving grazing and browsing habitat, agricultural clearing, and enhancing vital ethnobotanical plants (Barrett 1980). Bison (Bos bison) and prairie elk (Cervus elaphus) were the main herbivores in central tallgrass prairies. Herbivory occurred via mob grazing with large herds of animals rapidly moving across the prairie as they grazed. These continuous disturbances provided critical conditions for perpetuating the native savanna ecosystem (LANDFIRE 2009).

Drought and windthrow have also played a role in shaping this ecological site. The periodic episodes of reduced soil moisture in conjunction with the well-drained soils have favored the proliferation of plant species tolerant of such conditions. Drought can also slow the growth of plants and result in dieback of certain species. Damage to trees from storms can vary from minor, patchy effects of individual trees to stand effects that temporarily affect community structure and species richness and diversity (Irland 2000; Peterson 2000). When coupled with fire and herbivory, periods of drought can greatly delay the establishment of woody vegetation (Pyne et al. 1996).

Today, Sandy Upland Savannas are considered to be extirpated from the MLRA, having been converted for agricultural production (NatureServe 2015). Remnants that do exist have had fire suppressed long enough to allow the site to convert to a closed canopy forest. A return to the historic plant community may not be possible following extensive land modification, but long-term conservation agriculture or savanna reconstruction efforts can help to restore some biotic diversity and ecological function. The state-and-transition model that follows provides a detailed description of each state, community phase, pathway, and transition. This model is based on available experimental research, field observations, literature reviews, professional consensus, and interpretations.

State 1

Reference State

The reference plant community is categorized as a sand savanna community, dominated by herbaceous vegetation with sparse trees. The two community phases within the reference state are dependent on fire and large mammal herbivory. The amount and duration of grazing alters species composition, cover, and extent, while regular fire intervals keep woody species from dominating. Drought and windthrow have more localized impacts in the reference phases, but do contribute to overall species composition, diversity, cover, and productivity.

Community 1.1

Black Oak/Little Bluestem – Roundhead Lespedeza

Sites in this reference community phase are dominated by prairie grasses and forbs with scattered trees. Black oak is the dominant tree species, but white oak and northern pin oak may occur (NatureServe 2015). Vegetative cover is continuous, and trees comprise no more than 20 percent canopy cover (LANDFIRE 2009). Little bluestem, Pennsylvania sedge, and big bluestem are the dominant grasses. Characteristic forbs include roundhead lespedeza, field pussytoes (Antennaria neglecta Greene), woman’s tobacco (Antennaria plantaginifolia (L.) Richardson), flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollate L.), and fringeleaf wild petunia (Ruellia humilis Nutt.) (Delong and Hooper 1996; NatureServe 2015). Frequent surface fires occurring approximately every five years in conjunction with native grazing will maintain this phase, but an extended fire return interval would allow more woody species development shifting the community to phase 1.2 (LANDFIRE 2009).

Community 1.2

Black Oak/American Hazelnut – New Jersey Tea/Little Bluestem – Roundhead Lespedeza

This reference community phase represents natural succession as a result of an extended fire return interval, such as from drought. The lack of fire allows woody species, such as American hazelnut, New Jersey tea, and fragrant sumac to develop as clumps in the shrub layer. Trees mature as well and canopy closure ranges from 21 to 60 percent (LANDFIRE 2009). The canopy is still considered open, but forbs may increase their dominance as the shrub and tree cover increases (NatureServe 2015).

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Natural succession following an extended fire return interval.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Natural succession following a large replacement fire.

State 2

Fire-suppressed State

Long-term fire suppression can transition the reference plant community from an open savanna to a closed canopy forest. As the natural fire regime is removed from the landscape, encroachment and dominance by shade-tolerant, fire-intolerant species ensues (Asbjornsen et al. 2005). This results in a positive feedback loop of mesophication whereby plant community succession continuously creates cool, damp shaded conditions that perpetuate a closed canopy ecosystem (Nowacki and Abrams 2008). Succession to this forested state can occur in as little as 25 years from the last fire (LANDFIRE 2009).

Community 2.1

Black Oak – White Oak/American Hazelnut/Pennsylvania Sedge

This community phase represents the early stages of long-term fire suppression. In the absence of fire, trees and shrubs can become dominant, shifting the community structure from an open to a closed woodland with high stem density. Black oak is the dominant tree, but white oak and northern pin oak mature as well. Trees are very large (>33 inches DBH) and cover ranges from 61 to 80 percent (LANDFIRE 2009). American hazelnut can remain in the shrub layer during this closed woodland phase (Colandonato 1993). Under the heavier shade, the herbaceous sun-loving prairie species are replaced with species tolerant of moderate shading.

Community 2.2

Black Oak – White Oak/Pennsylvania Sedge – American Hogpeanut

Sites falling into this community phase have a well-established tree canopy that ranges from 81 to 100 percent (LANDFIRE 2009). Tree densities may reach as high as several hundred trees per hectare, and tree size class is reduced under increasing competition for resources. Under these closed-canopy stands, the shrub layer is nearly excluded while Pennsylvania sedge may form dense sods. Forb diversity is limited and may include American hogpeanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata (L.) Fernald), spotted geranium (Geranium maculatum L.), and feathery false lily of the valley (Maianthemum racemosum (L.) Link) (NatureServe 2015).

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Continued fire suppression.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Severe disturbance event such as a replacement fire, severe drought, or windstorm.

State 3

Forage State

The forage state occurs when the reference state is converted to a farming operation that emphasizes domestic livestock production known as grassland agriculture. Fire suppression, periodic cultural treatments (e.g., clipping, drainage, soil amendment applications, planting new species and/or cultivars, mechanical harvesting) and grazing by domesticated livestock transition and maintain this state (USDA-NRCS 2003). Early settlers seeded non-native species, such as smooth brome and Kentucky bluegrass, to help extend the grazing season (Smith 1998). Over time, as lands were continuously harvested or grazed by herds of cattle, the non-native species were able to spread and expand across the landscape, reducing the native species diversity and ecological function.

Community 3.1

Hayfield

Sites in this community phase consist of forage plants that are planted and mechanically harvested. Mechanical harvesting removes much of the aboveground biomass and nutrients that feed the soil microorganisms (Franzluebbers et al. 2000; USDA-NRCS 2003). As a result, soil biology is reduced leading to decreases in nutrient uptake by plants, soil organic matter, and soil aggregation. Frequent biomass removal can also reduce the site’s carbon sequestration capacity (Skinner 2008).

Community 3.2

Continuous Pastured Grazing

This community phase is characterized by continuous grazing where domestic livestock graze a pasture for the entire season. Depending on stocking density, this can result in lower forage quality and productivity, weed invasions, and uneven pasture use. Continuous grazing can also increase the amount of bare ground and erosion and reduce soil organic matter, cation exchange capacity, water-holding capacity, and nutrient availability and retention (Bharati et al. 2002; Leake et al. 2004; Teague et al. 2011). Smooth brome, Kentucky bluegrass, and white clover (Trifolium repens L.) are common pasture species used in this phase. Their tolerance to continuous grazing has allowed these species to dominate, sometimes completely excluding the native vegetation.

Community 3.3

Periodic-rest Pastured Grazing

This community phase is characterized by periodic-rest grazing where the pasture has been subdivided into several smaller paddocks. Subdividing the pasture in this way allows livestock to utilize one or a few paddocks, while the remaining area is rested allowing plants to restore vigor and energy reserves, deepen root systems, develop seeds, as well as allow seedling establishment (Undersander et al. 2002; USDA-NRCS 2003). Periodic-rest pastured grazing include deferred periods, rest periods, and periods of high intensity – low frequency, and short duration methods. Vegetation is generally more diverse and can include orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.), timothy (Phleum pretense L.), red clover (Trifolium pratense L.), and alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). The addition of native prairie species can further bolster plant diversity and, in turn, soil function. This community phase promotes numerous ecosystem benefits including increasing biodiversity, preventing soil erosion, maintaining and enhancing soil quality, sequestering atmospheric carbon, and improving water yield and quality (USDA-NRCS 2003).

Pathway 3.1A

Community 3.1 to 3.2

Mechanical harvesting is replaced with domestic livestock utilizing continuous grazing.

Pathway 3.1B

Community 3.1 to 3.3

Mechanical harvesting is replaced with domestic livestock utilizing periodic-rest grazing.

Pathway 3.2A

Community 3.2 to 3.1

Domestic livestock are removed, and mechanical harvesting is implemented.

Pathway 3.2B

Community 3.2 to 3.3

Periodic-rest grazing replaces continuous grazing.

Pathway 3.3B

Community 3.3 to 3.1

Domestic livestock are removed, and mechanical harvesting is implemented.

Pathway 3.3A

Community 3.3 to 3.2

Continuous grazing replaces periodic-rest grazing.

State 4

Cropland State

The continuous use of tillage, row-crop planting, and chemicals (i.e., herbicides, fertilizers, etc.) has effectively eliminated the reference community and many of its natural ecological functions in favor of crop production. Corn and soybeans are the dominant crops for the site, and oats (Avena L.) and alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) may be rotated periodically. These areas are likely to remain in crop production for the foreseeable future.

Community 4.1

Conventional Tillage Field

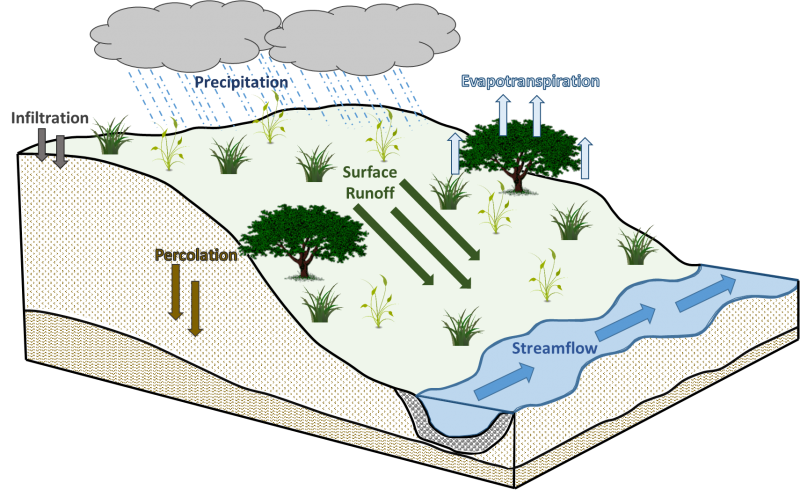

Sites in this community phase typically consist of monoculture row-cropping maintained by conventional tillage practices. They are cropped in either continuous corn or alternating periods of corn and soybean crops. The frequent use of deep tillage, low crop diversity, and bare soil conditions during the non-growing season negatively impacts soil health. Under these practices, soil aggregation is reduced or destroyed, soil organic matter is reduced, erosion and runoff are increased, and infiltration is decreased, which can ultimately lead to undesirable changes in the hydrology of the watershed (Tomer et al. 2005).

Community 4.2

Conservation Tillage Field

This community phase is characterized by periodically alternating crops and utilizing various conservation tillage methods to promote soil health and reduce erosion. Conservation tillage methods include strip-till, ridge-till, vertical-till, or no-till planting operations. Strip-till keeps seedbed preparation to narrow bands less than one-third the width of the row where crop residue and soil consolidation are left undisturbed in-between seedbed areas. Strip-till planting may be completed in the fall and nutrient application either occurs simultaneously or at the time of planting. Ridge-till uses specialized equipment to create ridges in the seedbed and vegetative residue is left on the surface in between the ridges. Weeds are controlled with herbicides and/or cultivation, seedbed ridges are rebuilt during cultivation, and soils are left undisturbed from harvest to planting. Vertical-till operations employ machinery that lightly tills the soil and cuts up crop residue, mixing some of the residue into the top few inches of the soil while leaving a large portion on the surface. No-till management is the most conservative, disturbing soils only at the time of planting and fertilizer application. Compared to conventional tillage operations, conservation tillage methods can improve soil ecosystem function by reducing soil erosion, increasing organic matter and water availability, improving water quality, and reducing soil compaction.

Community 4.3

Conservation Tillage Field/Alternative Crop Field

This community phase applies conservation tillage methods as described above as well as adds cover crop practices. Cover crops typically include nitrogen-fixing species (e.g., legumes), small grains (e.g., rye, wheat, oats), or forage covers (e.g., turnips, radishes, rapeseed). The addition of cover crops not only adds plant diversity but also promotes soil health by reducing soil erosion, limiting nitrogen leaching, suppressing weeds, increasing soil organic matter, and improving the overall soil ecosystem. In the case of small grain cover crops, surface cover and water infiltration are increased, while forage covers can be used to graze livestock or support local wildlife. Of the three community phases for this state, this phase promotes the greatest soil sustainability and improves ecological functioning within a row crop operation.

Pathway 4.1A

Community 4.1 to 4.2

Tillage operations are greatly reduced, alternating crops occurs on a regular interval, and crop residue remains on the soil surface.

Pathway 4.1B

Community 4.1 to 4.3

Tillage operations are greatly reduced or eliminated, alternating crops occurs on a regular interval, crop residue remains on the soil surface, and cover crops are planted following crop harvest.

Pathway 4.2A

Community 4.2 to 4.1

Intensive tillage is utilized, and monoculture row-cropping is established.

Pathway 4.2B

Community 4.2 to 4.3

Cover crops are implemented to minimize soil erosion.

Pathway 4.3B

Community 4.3 to 4.1

Intensive tillage is utilized, cover crops practices are abandoned, monoculture row-cropping is established on a more-or-less continuous basis.

Pathway 4.3A

Community 4.3 to 4.2

Cover crop practices are abandoned.

State 5

Reconstructed Sand Savanna State

Savanna reconstructions have become an important tool for repairing natural ecological functions and providing habitat protection for numerous grassland dependent species. Because the historic plant and soil biota communities of the tallgrass habitats were highly diverse with complex interrelationships, historic savanna replication cannot be guaranteed on landscapes that have been so extensively manipulated for extended timeframes (Kardol and Wardle 2010; Fierer et al. 2013). Therefore, ecological restoration should aim to aid the recovery of degraded, damaged, or destroyed ecosystems. A successful restoration will have the ability to structurally and functionally sustain itself, demonstrate resilience to the natural ranges of stress and disturbance, and create and maintain positive biotic and abiotic interactions (SER 2002). The reconstructed savanna state is the result of a long-term commitment involving a multi-step, adaptive management process. Oak plantings or selective thinning of non-oak species will be required to reproduce the overstory canopy (Asbjornsen et al. 2005). Diverse, species-rich seed mixes may be important to utilize as they allow the site to undergo successional stages that exhibit changing composition and dominance over time (Smith et al. 2010). On-going management via prescribed fire and/or light grazing will help the site progress from an early successional community dominated by annuals and some weeds to a later seral stage composed of native perennial grasses, forbs, shrubs, and eventually mature oaks. Establishing a prescribed fire regime that mimics natural disturbance patterns can increase native species cover and diversity while reducing cover of non-native forbs and grasses. Light grazing alone can help promote species richness, while grazing accompanied with fire can control the encroachment of undesirable woody vegetation (Brudvig et al. 2007).

Community 5.1

Early Successional Reconstructed Oak Savanna

This community phase represents early community assembly and is highly dependent on the timing and priority of planting and/or tree thinning operations and the herbaceous seed mix utilized. If oak plantings are needed, acorns should be planted shortly after harvest as acorns germinate shortly after seedfall and require no cold stratification. Browse protection may need to be installed to protect newly established seedlings from animal predation. If selective tree removal is needed, canopy reduction should encompass between 16 to 45 percent of the undesirable species in a single year (Asbjornsen et al. 2005). The seed mix should look to include a diverse mix of native cool-season and warm-season annual and perennial grasses and forbs typical of the reference state. Native, cool-season annuals can help to provide litter that promotes cool, moist soil conditions to the benefit of the other species in the seed mix. The first season following site preparation and seeding will typically result in annuals and other volunteer species forming a majority of the vegetative cover. Control of non-native species, particularly perennial species, is crucial at this point to ensure they do not establish before the native vegetation (Martin and Wilsey 2012). After the first season, native warm-season grasses should begin to become more prominent on the landscape and over time close the canopy.

Community 5.2

Late Successional Reconstructed Oak Savanna

Appropriately timed disturbance regimes (e.g., prescribed fire) applied to the early successional community phase can help increase the beta diversity, pushing the site into a late successional community phase over time. While oak savanna communities are dominated by grasses, these species can suppress forb establishment and reduce overall diversity and ecological functioning (Martin and Wilsey 2006; Williams et al. 2007). Reducing accumulated plant litter from such tallgrasses as big bluestem and Indiangrass allows more light and nutrients to become available for forb recruitment, allowing for greater ecosystem complexity (Wilsey 2008).

Pathway 5.1A

Community 5.1 to 5.2

Selective herbicides are used to control non-native species, and prescribed fire and/or light grazing help to increase the native species diversity and control non-oak woody vegetation.

Pathway 5.2B

Community 5.2 to 5.1

Reconstruction experiences a decrease in native species diversity from drought or improper timing of management actions (e.g., reduced fire frequency, use of non-selective herbicides).

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Long-term fire suppression transitions the site to the fire-suppressed state (2).

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Cultural treatments to enhance forage quality and yield transitions the site to the forage state (3).

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

Tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition the site to the cropland state (4).

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Cultural treatments to enhance forage quality and yield transitions the site to the forage state (3).

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

Tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition this site to the cropland state (4).

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 5

Site preparation, invasive species control, and seeding native species transition this site to the reconstructed sand savanna state (5).

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

Land abandonment transitions the site to the fire-suppressed scrub state (2).

Transition T3B

State 3 to 4

Tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition this site to the cropland state (4).

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 5

Site preparation, tree planting, invasive species control, and seeding native species transition this site to the reconstructed sand savanna state (5).

Transition T4A

State 4 to 2

Land abandonment transitions the site to the fire-suppressed scrub state (2).

Transition T4B

State 4 to 3

Cultural treatments to enhance forage quality and yield transitions the site to the forage state (3).

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 5

Site preparation, tree planting, invasive species control, and seeding native species transition this site to the reconstructed sand savanna state (5).

Transition T5A

State 5 to 2

Fire suppression and removal of active management transitions this site to the fire-suppressed state (2).

Transition T5B

State 5 to 3

Cultural treatments to enhance forage quality and yield transition the site to the forage state (3).

Transition T5C

State 5 to 4

Tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition this site to the cropland state (4).