Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F109XY003MO

Loess Upland Woodland

Last updated: 7/01/2024

Accessed: 11/23/2024

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

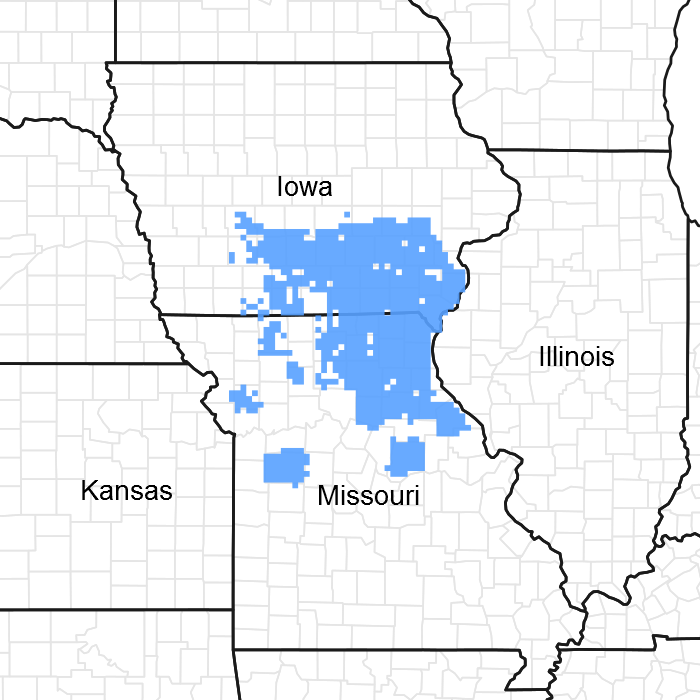

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 109X–Iowa and Missouri Heavy Till Plain

The Iowa and Missouri Heavy Till Plain is an area of rolling hills interspersed with interfluve divides and alluvial valleys. Elevation ranges from about 660 feet (200 meters) along the lower reaches of rivers, to about 980 feet (300 meters) on stable interfluve summits in southern Iowa. Relief is about 80 to 160 feet (25 to 50 meters) between major streams and adjacent interfluve summits. Most of the till plain drains south to the Missouri River via the Grand and Chariton River systems, but the northeastern portion drains southeast to the Mississippi River. Loess caps the pre-Illinoisan aged till on interfluves, whereas the till is exposed on side slopes. Mississippian aged limestone and Pennsylvanian aged sandstone and shale crop out on lower slopes in some areas.

Classification relationships

Terrestrial Natural Community Type in Missouri (Nelson, 2010):

The reference state for this ecological site is most similar to a Dry-Mesic Loess/Glacial Till Woodland.

Missouri Department of Conservation Forest and Woodland Communities (Missouri Department of Conservation, 2006):

The reference state for this ecological site is most similar to a Mixed Oak Loess/Glacial Till Woodland.

National Vegetation Classification System Vegetation Association (NatureServe, 2010):

The reference state for this ecological site is most similar to a Quercus alba - (Carya ovata) / Carex pensylvanica Glaciated Woodland (CEGL002134).

Geographic relationship to the Missouri Ecological Classification System (Nigh & Schroeder, 2002):

This ecological site occurs in many Land Type Associations, primarily within the following Subsections:

Chariton River Hills

Claypan Till Plains

Mississippi River Hills

Wyaconda River Dissected Till Plains

Ecological site concept

NOTE: This is a “provisional” Ecological Site Description (ESD) that is under development. It contains basic ecological information that can be used for conservation planning, application and land management. As additional information is collected, analyzed and reviewed, this ESD will be refined and published as “Approved”.

Loess Upland Woodlands are more prevalent in the eastern part of the MLRA and adjacent areas, where woodlands and forests were historically present on hillslopes. This is the principal ecological site of woodland hillslope summits in the MLRA. Till woodland or forest ecological sites are typically downslope. Soils are very deep, with no rooting restrictions. The reference plant community is woodland with an overstory dominated by white oak and black oak, and a ground flora of native grasses and forbs.

Associated sites

| F109XY007MO |

Till Upland Woodland Till Upland Woodlands are downslope, on shoulders and backslopes. |

|---|---|

| F109XY009MO |

Till Protected Backslope Forest Till Protected Backslope Woodlands are downslope, on steep backslopes with northern to eastern aspects. |

| F109XY022MO |

Till Exposed Backslope Woodland Till Exposed Backslope Woodlands are downslope, on steep backslopes with southern to western aspects. |

Similar sites

| F109XY007MO |

Till Upland Woodland Till Upland Woodlands have a similar overstory composition but seasonal wetness can create differences in the ground layer composition. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Quercus alba |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Rhus aromatica |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Elymus virginicus |

Physiographic features

This site is on upland summit crests and shoulders, with slopes of 3 to 9 percent. The site generates runoff to adjacent, downslope ecological sites. This site does not flood.

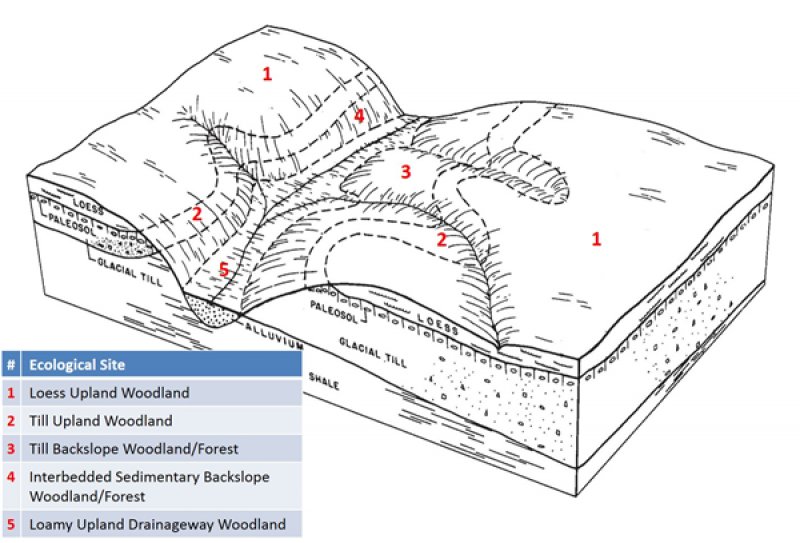

The following figure (adapted from Seaholm, 1981) shows the typical landscape position of this ecological site, and landscape relationships among the major ecological sites in the uplands. The site is within the area labeled “1”, generally upslope from ecological sites formed in till.

Figure 2. Landscape relationships for this ecological site

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Ridge

(2) Hill |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 162 – 411 m |

| Slope | 3 – 14% |

| Water table depth | 30 – 122 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The Iowa and Missouri Heavy Till Plain MLRA has a continental type of climate marked by strong seasonality. In winter, dry-cold air masses, unchallenged by any topographic barriers, periodically swing south from the northern plains and Canada. If they invade reasonably humid air, snowfall and rainfall result. In summer, moist, warm air masses, equally unchallenged by topographic barriers, swing north from the Gulf of Mexico and can produce abundant amounts of rain, either by fronts or by convectional processes. In some summers, high pressure stagnates over the region, creating extended droughty periods. Spring and fall are transitional seasons when abrupt changes in temperature and precipitation may occur due to successive, fast-moving fronts separating contrasting air masses.

This MLRA experiences small regional differences in climates that grade inconspicuously into each other. The basic gradient for most climatic characteristics is along a line from north to south. Both mean annual temperature and precipitation exhibit fairly minor gradients along this line.

Mean January minimum temperature follows the north-to-south gradient. However, mean July maximum temperature shows hardly any geographic variation in the region. Mean July maximum temperatures have a range of only two to three degrees across the region.

Mean annual precipitation varies along the same gradient as temperature – lower annual precipitation in the north, higher in the south. Seasonality in precipitation is very pronounced due to strong continental influences. June precipitation, for example, averages four to five times greater than January precipitation.

During years when precipitation is normal, moisture is stored in the soil profile during the winter and early spring, when evaporation and transpiration are low. During the summer months the loss of water by evaporation and transpiration is high, and if rainfall fails to occur at frequent intervals, drought will result. Drought directly influences ecological communities by limiting water supplies, especially at times of high temperatures and high evaporation rates. Drought indirectly affects ecological communities by increasing plant and animal susceptibility to the probability and severity of fire. Frequent fires encourage the development of grass/forb dominated communities and understories.

Superimposed upon the basic MLRA climatic patterns are local topographic influences that create topoclimatic, or microclimatic variations. For example, air drainage at nighttime may produce temperatures several degrees lower in valley bottoms than on side slopes. At critical times during the year, this phenomenon may produce later spring or earlier fall freezes in valley bottoms. Slope orientation is an important topographic influence on climate. Summits and south-and-west-facing slopes are regularly warmer and drier, supporting more grass dominated communities than adjacent north- and-east-facing slopes that are cooler and moister that support more woody dominated communities. Finally, the climate within a canopied forest ecological site is measurably different from the climate of the more open grassland or savanna ecological sites.

Source: University of Missouri Climate Center - http://climate.missouri.edu/climate.php;

Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin, United States Department of Agriculture Handbook 296 - http://soils.usda.gov/survey/geography/mlra/

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 151-156 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 182-187 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 965-1,016 mm |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 150-158 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 181-189 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 914-1,067 mm |

| Frost-free period (average) | 154 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 185 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 991 mm |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 6. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 7. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 8. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BLOOMFIELD 1 WNW [USC00130753], Bloomfield, IA

-

(2) DONNELLSON [USC00132299], Donnellson, IA

-

(3) LONG BRANCH RSVR [USC00235050], Macon, MO

-

(4) MEMPHIS [USC00235492], Memphis, MO

Influencing water features

The water features of this upland ecological site include evapotranspiration, surface runoff, and drainage. Each water balance component fluctuates to varying extents from year-to-year. Precipitation and drainage are highly variable between years. Seasonal variability differs for each water component. Precipitation generally occurs as single day events. Evapotranspiration is lowest in the winter and peaks in the summer. The surface runoff pulse is greatly influenced by extreme events. Conversion to cropland or other high intensity land uses tends to increase runoff, but also decreases evapotranspiration. Depending on the situation, this might increase runoff discharge, and decrease baseflow in receiving streams.

Soil features

These soils have no major rooting restriction. The soils were formed under woodland vegetation, and have thin, light-colored surface horizons. Parent material is loess. Some soils have residuum in the lower part. The soils have silt loam surface horizons. Subsoils are silty clay loam to silty clay. These soils are slightly affected by seasonal wetness. Soil series associated with this site include Clinton, Gorin, and Weller.

The accompanying picture of the Weller series shows a thin, light-colored surface horizon overlying the brown silty clay loam subsoil. Roots can be seen throughout the soil profile.

Figure 9. Soil profile of Weller series

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Loess

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Silt loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Clayey |

| Drainage class | Somewhat poorly drained to moderately well drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow to slow |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

15.24 – 17.78 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

0% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

4.5 – 6 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0% |

Ecological dynamics

Information contained in this section was developed using historical data, professional experience, field reviews, and scientific studies. The information presented is representative of very complex vegetation communities. Key indicator plants, animals and ecological processes are described to help inform land management decisions. Plant communities will differ across the MLRA because of the naturally occurring variability in weather, soils, and aspect. The Reference Plant Community is not necessarily the management goal. The species lists are representative and are not botanical descriptions of all species occurring, or potentially occurring, on this site. They are not intended to cover every situation or the full range of conditions, species, and responses for the site.

This ecological site is a well-developed woodland dominated by an overstory of white oak, along with occasional black oak. The canopy is moderately tall (65 to 80 feet [20 to 24 meters]) with a 55 to 75 percent canopy closure. This community is more structurally diverse than the adjacent protected slopes. Increased light from a more open canopy causes a diversity of woodland ground flora species to flourish. Woodlands are distinguished from forest, by their relatively open understory, and the presence of sun-loving ground flora species. Characteristic plants in the ground flora can be used to gauge the restoration potential of a stand along with remnant open-grown old-age trees, and tree height growth.

Because of their proximity to prairies, fire played a significant role in the maintenance of these ecological sites which likely burned at least once every 3 to 10 years. These periodic fires kept woodlands open, removed the litter, and stimulated the growth and flowering of the grasses and forbs. During fire free intervals, woody understory species increased and the herbaceous understory diminished. The return of fire would open the woodlands up again and stimulate the abundant ground flora.

Loess Upland Woodlands were also subjected to occasional disturbances from wind and ice, as well as grazing by native large herbivores such as bison, elk, and white-tailed deer. Wind and ice would have periodically opened the canopy up by knocking over trees or breaking substantial branches off canopy trees. Grazing by native herbivores would have effectively kept understory conditions more open, creating conditions more favorable to oak reproduction and woodland ground flora species.

Today, many of these ecological sites have been cleared and converted to pasture or have undergone repeated timber harvest and domestic grazing. Most existing forested ecological sites have a younger (50 to 80 years) canopy layer whose species composition and quality has been altered by timber harvesting practices. In the long-term absence of fire, woody species, especially hickory and sugar maple, encroach into these woodlands. Once established, these woody plants can quickly fill the existing understory increasing shade levels with a greatly diminished ground flora. Removal of the younger understory and the application of prescribed fire have proven to be effective restoration means.

Uncontrolled domestic grazing has also impacted these communities, further diminishing the diversity of native plants and introducing species that are tolerant of grazing, such as coralberry, gooseberry, and Virginia creeper. Grazed sites also have a more open understory. In addition, soil compaction and soil erosion from grazing can be a problem and lower site productivity.

These ecological sites are moderately productive. Oak regeneration is typically problematic. Eastern hop hornbeam and hickories are often dominant competitors in the understory. Maintenance of the oak component will require disturbances that will encourage more sun adapted species and reduce shading effects. Single tree selection timber harvests are common in this region and often results in removal of the most productive trees (high grading) in the stand leading to poorer quality timber and a shift in species composition away from more valuable oak species. Better planned single tree selection or the creation of group openings can help regenerate and maintain more desirable oak species and increase vigor on the residual trees.

Clearcutting also occurs and results in dense, even-aged stands dominated by oak. This may be most beneficial for existing stands whose composition has been highly altered by past management practices. However, without some thinning of the dense stands and the application of prescribed fire, the ground flora diversity can be shaded out and diversity of the stand may suffer.

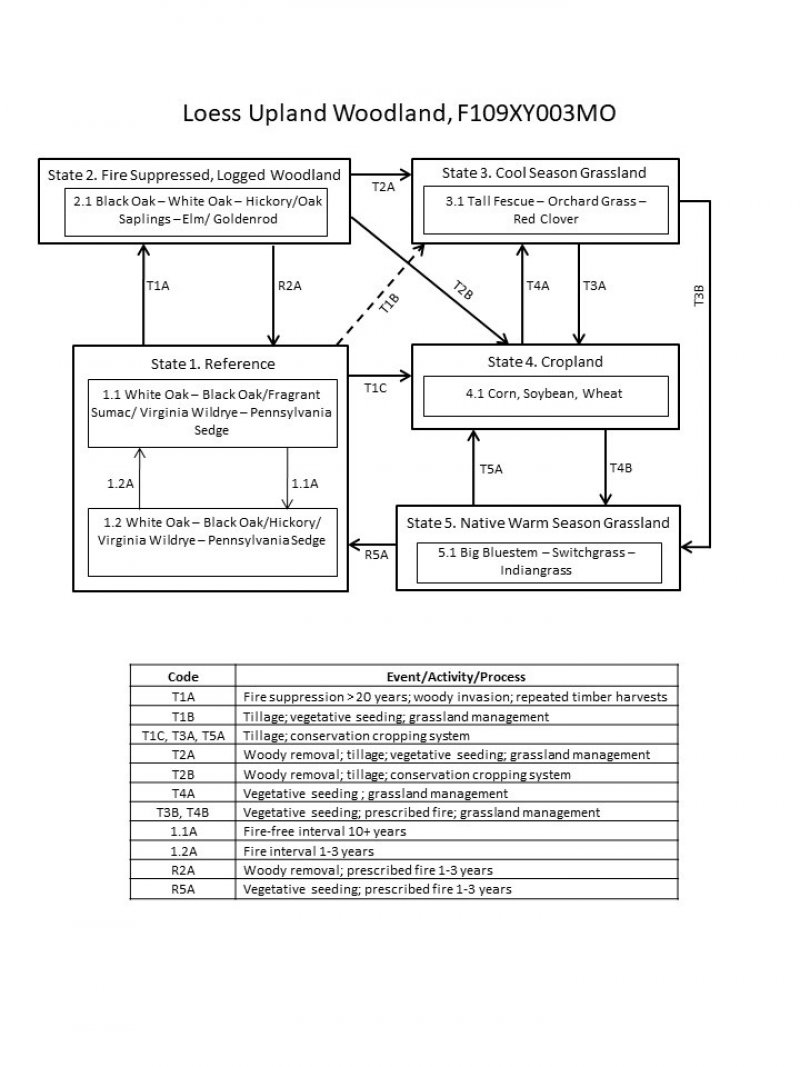

A State and Transition Diagram follows. Detailed descriptions of each state, transition, plant community, and pathway follow the model. This model is based on available experimental research, field observations, professional consensus, and interpretations. It is likely to change as knowledge increases.

State and transition model

Figure 10. State and Transition Diagram for Loess Upland Woodland

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

States 1 and 5 (additional transitions)

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference

The historical reference state for this ecological site was old growth oak woodland. The woodland was dominated by white oak and black oak. Maximum tree age was likely 150-300 years. Periodic disturbances from fire, wind or ice as well as grazing by native large herbivores maintained the woodland structure and diverse ground flora species. Long disturbance-free periods allowed an increase in both the density of trees and the abundance of shade tolerant species. Two community phases are recognized in the Reference State, with shifts between phases based on disturbance frequency. Reference states are very rare today. Fire suppression has resulted in increased canopy density, which has affected the abundance and diversity of ground flora. Most Reference States are currently altered because of timber harvesting, domestic grazing or clearing and conversion to grassland or cropland.

Dominant plant species

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

black oak (Quercus velutina), tree

-

fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica), shrub

-

Virginia wildrye (Elymus submuticus), other herbaceous

-

Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), other herbaceous

Community 1.1

White Oak-Black Oak/Aromatic Sumac/Virginia Wild Rye-Pennsylvania Sedge

This phase has an overstory that is dominated by white oak and black oak with hickory and post oak also present. This woodland community has a two-tiered structure with an open understory and a dense, diverse herbaceous ground flora. Periodic disturbances including fire, ice and wind create canopy gaps, allowing white oak and black oak to successfully reproduce and remain in the canopy.

Forest overstory. The Forest Overstory Species list is based on commonly occurring species listed in Nelson (2010).

Forest understory. The Forest Understory Species list is based on commonly occurring species listed in Nelson (2010).

Dominant plant species

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

black oak (Quercus velutina), tree

-

fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica), shrub

-

Virginia wildrye (Elymus submuticus), other herbaceous

-

Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), other herbaceous

Community 1.2

White Oak-Black Oak/Hickory/Virginia Wild Rye-Pennsylvania Sedge

Figure 11. Dark Hollow Conservation Area

This phase is similar to community phase 1.1 but oak and hickory understory densities are increasing due to longer periods of fire suppression. Displacement of some grasses and forbs may be occurring due to shading and competition from the increased densities of oak and hickory saplings in the understory.

Forest overstory. The Forest Overstory Species list is based on reconnaissance-level plots, as well as commonly occurring species listed in Nelson (2010). Species identified from plot data include cover percentages and canopy heights. Species not found in plots, but listed in Nelson, do not include cover and canopy data.

Forest understory. The Forest Understory list is based on reconnaissance-level plots, as well as commonly occurring species listed in Nelson (2010). Species identified from plot data include cover percentages and canopy heights. Species not found in plots, but listed in Nelson, do not include cover and canopy data. Note that plot data for canopy heights are by height class, not actual species heights.

Dominant plant species

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

black oak (Quercus velutina), tree

-

red hickory (Carya ovalis), shrub

-

Virginia wildrye (Elymus submuticus), other herbaceous

-

Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), other herbaceous

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Fire-free interval 10+ years

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Fire interval 1-3 years

State 2

Fire Suppressed, Logged Woodland

Composition is likely altered from the Reference State depending on tree selection during harvest. This state will slowly increase in more shade tolerant species and white oak will become less dominant and is also dense because of fire suppression. Without periodic canopy disturbance, stem density and fire intolerant species, like hickory, will increase in abundance. Uncontrolled grazing if present will also have an impact on community composition and understory quality further diminishing the diversity of native plants and introducing species that are tolerant of grazing, such as buckbrush, gooseberry, and Virginia creeper.

Dominant plant species

-

black oak (Quercus velutina), tree

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

red hickory (Carya ovalis), tree

-

elm (Ulmus), tree

-

goldenrod (Oligoneuron), other herbaceous

Community 2.1

Black Oak-White Oak-Hickory/Oak Saplings-Elm/Goldenrod

Dominant plant species

-

white oak (Quercus alba), tree

-

red hickory (Carya ovalis), tree

-

elm (Ulmus), tree

-

goldenrod (Oligoneuron), other herbaceous

State 3

Cool Season Grassland

Conversion of other states to non-native cool season species such as tall fescue, orchard grass, and red clover has been common. Occasionally, these pastures will have scattered oaks. Long term uncontrolled grazing can cause significant soil erosion and compaction. A return to the Reference State may be impossible, requiring a very long term series of management options.

Dominant plant species

-

orchardgrass (Dactylis), grass

-

red clover (Trifolium pratense), grass

Community 3.1

Tall Fescue-Orchard Grass-Red Clover

State 4

Cropland

This is a State that exists currently with intensive cropping of corn, soybeans, and wheat occurring especially when commodity prices are high. Some conversion to cool season grassland occurs for a limited period of time before transitioning back to cropland. Limited acres are sometimes converted to native warm season grassland.

Community 4.1

Corn, Soybean, Wheat

Dominant plant species

State 5

Native Warm Season Grassland

Conversion from the Cool Season Grassland (State 3) or the Cropland (State 4) to this State is increasing due to renewed interest in warm season grasses as a supplement to cool season grazing systems or as a native restoration activity. Restoration to the Reference state will require substantial restoration time and management inputs.

Dominant plant species

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), other herbaceous

-

switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), other herbaceous

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum), other herbaceous

Community 5.1

Big Bluestem-Switchgrass-Indiangrass

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Fire suppression >20 years; woody invastion; repeated timber harvests

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Tillage; vegetative seeding; grassland management

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

Tillage; conservation cropping system

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Woody removal; prescribed fire 1-3 years

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Woody removal; tillage; vegetative seeding; grassland management

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

Woody removal; tillage; conservation cropping system

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Tillage; conservation cropping system

Transition T3B

State 3 to 5

Vegetative seeding; prescribed fire; grassland management

Restoration pathway T4A

State 4 to 3

Vegetative seeding; grassland management

Transition T4B

State 4 to 5

Vegetative seeding; prescribed fire; grassland management

Restoration pathway R5A

State 5 to 1

Vegetative seeding; prescribed fire 1-3 years

Restoration pathway T5A

State 5 to 4

Tillage; conservation cropping system

Additional community tables

Table 5. Community 1.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | – | 40–70 | – | – |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | – | 20–40 | – | – |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | – | 0–10 | – | – |

Table 6. Community 1.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| Pennsylvania sedge | CAPE6 | Carex pensylvanica | Native | – | 10–30 | |

| rock muhly | MUSO | Muhlenbergia sobolifera | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | Native | – | 10–20 | |

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| hairy woodland brome | BRPU6 | Bromus pubescens | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| parasol sedge | CAUM4 | Carex umbellata | Native | – | 10–20 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| elmleaf goldenrod | SOUL2 | Solidago ulmifolia | Native | – | 5–30 | |

| hairy sunflower | HEHI2 | Helianthus hirsutus | Native | – | 10–30 | |

| eastern purple coneflower | ECPU | Echinacea purpurea | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| nakedflower ticktrefoil | DENU4 | Desmodium nudiflorum | Native | – | 10–20 | |

| slender lespedeza | LEVI7 | Lespedeza virginica | Native | – | 10–20 | |

| Canadian blacksnakeroot | SACA15 | Sanicula canadensis | Native | – | 10–20 | |

| eastern beebalm | MOBR2 | Monarda bradburiana | Native | – | 10–20 | |

| fourleaf milkweed | ASQU | Asclepias quadrifolia | Native | – | 10–20 | |

| Culver's root | VEVI4 | Veronicastrum virginicum | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| bluejacket | TROH | Tradescantia ohiensis | Native | – | 5–10 | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| fragrant sumac | RHAR4 | Rhus aromatica | Native | – | 10–30 | |

| New Jersey tea | CEAM | Ceanothus americanus | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| American hazelnut | COAM3 | Corylus americana | Native | – | 10–20 | |

Table 7. Community 1.2 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 15.2–22.9 | 10–75 | – | – |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | 9.1–22.9 | 10–50 | – | – |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | 15.2–22.9 | 5–25 | – | – |

Table 8. Community 1.2 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| Pennsylvania sedge | CAPE6 | Carex pensylvanica | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–50 | |

| hairy woodland brome | BRPU6 | Bromus pubescens | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| Muhlenberg's sedge | CAMU4 | Carex muehlenbergii | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | Native | – | – | |

| parasol sedge | CAUM4 | Carex umbellata | Native | – | – | |

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | Native | – | – | |

| rock muhly | MUSO | Muhlenbergia sobolifera | Native | – | – | |

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | Native | – | – | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| pointedleaf ticktrefoil | DEGL5 | Desmodium glutinosum | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 5–25 | |

| panicledleaf ticktrefoil | DEPA6 | Desmodium paniculatum | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| soft agrimony | AGPU | Agrimonia pubescens | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| American hogpeanut | AMBR2 | Amphicarpaea bracteata | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| shining bedstraw | GACO3 | Galium concinnum | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| hairy sunflower | HEHI2 | Helianthus hirsutus | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| elmleaf goldenrod | SOUL2 | Solidago ulmifolia | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| wild blue phlox | PHDI5 | Phlox divaricata | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| smooth blue aster | SYLAC | Symphyotrichum laeve var. concinnum | Native | – | – | |

| bluejacket | TROH | Tradescantia ohiensis | Native | – | – | |

| Culver's root | VEVI4 | Veronicastrum virginicum | Native | – | – | |

| fourleaf milkweed | ASQU | Asclepias quadrifolia | Native | – | – | |

| nakedflower ticktrefoil | DENU4 | Desmodium nudiflorum | Native | – | – | |

| eastern purple coneflower | ECPU | Echinacea purpurea | Native | – | – | |

| slender lespedeza | LEVI7 | Lespedeza virginica | Native | – | – | |

| eastern beebalm | MOBR2 | Monarda bradburiana | Native | – | – | |

| Canadian blacksnakeroot | SACA15 | Sanicula canadensis | Native | – | – | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| fragrant sumac | RHAR4 | Rhus aromatica | Native | 0.3–3 | 25–50 | |

| coralberry | SYOR | Symphoricarpos orbiculatus | Native | 0.1–3 | 0.1–2 | |

| burningbush | EUAT5 | Euonymus atropurpureus | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| Missouri gooseberry | RIMI | Ribes missouriense | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| Carolina rose | ROCA4 | Rosa carolina | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| northern dewberry | RUFL | Rubus flagellaris | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| stiff dogwood | COFO | Cornus foemina | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| common serviceberry | AMAR3 | Amelanchier arborea | Native | 0.1–3 | 0.1–1 | |

| New Jersey tea | CEAM | Ceanothus americanus | Native | – | – | |

| American hazelnut | COAM3 | Corylus americana | Native | – | – | |

|

Tree

|

||||||

| hophornbeam | OSVI | Ostrya virginiana | Native | 0.3–9.1 | 0.1–50 | |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | 0.1–3 | 0.1–10 | |

| white ash | FRAM2 | Fraxinus americana | Native | 0.3–3 | 1–5 | |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 2–5 | |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | 0.1–3 | 0.1–5 | |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | 0.1–3 | 0.1–5 | |

| American elm | ULAM | Ulmus americana | Native | 0.1–3 | 0.1–2 | |

| shingle oak | QUIM | Quercus imbricaria | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

| black cherry | PRSE2 | Prunus serotina | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–1 | |

|

Vine/Liana

|

||||||

| Virginia creeper | PAQU2 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 1–5 | |

Interpretations

Animal community

Wild turkey, white-tailed deer, and eastern gray squirrel depend on hard and soft mast food sources and are typical upland game species of this type.

Oaks provide hard mast; scattered shrubs provide soft mast; native legumes provide high-quality wildlife food; sedges and native cool-season grasses provide green browse; patchy native warm-season grasses provide cover and nesting habitat; and a diversity of forbs provides a diversity and abundance of insects. Post-burn areas can provide temporary bare-ground – herbaceous cover habitat important for turkey poults and quail chicks.

Bird species associated with mature communities include Indigo Bunting, Red-headed Woodpecker, Eastern Bluebird, Northern Bobwhite, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Broad-winged Hawk, Great-Crested Flycatcher, Summer Tanager, and Red-eyed Vireo.

Reptile and amphibian species associated with the Loess Upland Woodland include tiger salamander, small-mouthed salamander, ornate box turtle, northern fence lizard, five-lined skink, broad-headed skink, flat-headed snake, and rough earth snake. (MDC 2006)

Other information

Forestry

Management: Estimated site index values range from 55 to 65 for oak. Timber management opportunities are good. Create group openings of at least 2 acres. Large clearcuts should be minimized if possible to reduce impacts on wildlife and aesthetics. Uneven-aged management using single tree selection or group selection cuttings of ½ to 1 acre are other options that can be used if clear cutting is not desired or warranted. Using prescribed fire as a management tool could have a negative impact on timber quality, may not be fitting, or should be used with caution on a particular site if timber management is the primary objective. Favor white oak and northern red oak on higher productivity sites and post oak, chinkapin oak, black oak and scarlet oak on lower productivity sites.

Limitations: No major equipment restrictions or limitations exist. Erosion is a hazard when slopes exceed 15 percent. On steep slopes greater than 35%, traction problems increase and equipment use is not recommended.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Potential Reference Sites: Loess Upland Woodland

Plot DAHOCA03 – Gorin soil

Located in Dark Hollow CA, Sullivan County, MO.

Latitude: 40.323068

Longitude: -92.926944

Plot THHISP04 – Gorin soil

Located in Thousand Hills State Park, Adair County, MO.

Latitude: 40.154722

Longitude: - 92.641504

Other references

Anderson, R.C. 1990. The historic role of fire in North American grasslands. Pp. 8-18 in S.L. Collins and L.L. Wallace (eds.). Fire in North American tallgrass prairies. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Frost, C., 1996. Pre-settlement Fire Frequency Regimes of the United States: A First Approximation. Pages 70-81, Proceedings of the 20nd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Ecosystem Management: Shifting the Paradigm from Suppression to Prescription. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL.

MDC, 2006. Missouri Forest and Woodland Community Profiles. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2002. Woodland Suitability Groups. Missouri FOTG, Section II, Soil Interpretations and Reports. 30 pgs.

Natural Resources Conservation Service. Site Index Reports. Accessed May 2016. https://esi.sc.egov.usda.gov/ESI_Forestland/pgFSWelcome.aspx

NatureServe. 2010. Vegetation Associations of Missouri (revised). NatureServe, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Nelson, Paul W. 2010. The Terrestrial Natural Communities of Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Nigh, Timothy A., and Walter A. Schroeder. 2002. Atlas of Missouri Ecoregions. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Seaholm, James E. 1981. Soil Survey of Wapello County, Iowa. U.S. Dept. of Agric. Soil Conservation Service.

United States Department of Agriculture – Natural Resource Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS). 2006. Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbook 296. 682 pgs.

Contributors

Doug Wallace

Fred Young

Approval

Suzanne Mayne-Kinney, 7/01/2024

Acknowledgments

Missouri Department of Conservation and Missouri Department of Natural Resources personnel provided significant and helpful field and technical support in the development of this ecological site.

This site was originally approved on 07/28/2015 for publication.

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 11/23/2024 |

| Approved by | Suzanne Mayne-Kinney |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.