Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R109XY002MO

Loess Upland Prairie

Last updated: 7/01/2024

Accessed: 02/26/2026

General information

Approved. An approved ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model, enough information to identify the ecological site, and full documentation for all ecosystem states contained in the state and transition model.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 109X–Iowa and Missouri Heavy Till Plain

The Iowa and Missouri Heavy Till Plain is an area of rolling hills interspersed with interfluve divides and alluvial valleys. Elevation ranges from about 660 feet (201 meters) along the lower reaches of rivers, to about 980 feet (299 meters) on stable interfluve summits in southern Iowa. Relief is about 80 to 160 feet (24 to 49 meters) between major streams and adjacent interfluve summits. Most of the till plain drains south to the Missouri River via the Grand and Chariton River systems, but the northeastern portion drains southeast to the Mississippi River. Loess caps the pre-Illinoisan aged till on interfluves, whereas the till is exposed on side slopes. Mississippian aged limestone and Pennsylvanian aged sandstone and shale crop out on lower slopes in some areas.

Classification relationships

Terrestrial Natural Community Type in Missouri (Nelson, 2010):

The reference state for this ecological site is most similar to a Dry-Mesic Loess/Glacial Till Prairie.

National Vegetation Classification System Vegetation Association (NatureServe, 2010):

The reference state for this ecological site is most similar to Schizachyrium scoparium - Sorghastrum nutans - Bouteloua curtipendula Herbaceous Vegetation (CEGL002214).

Geographic relationship to the Missouri Ecological Classification System (Nigh & Schroeder, 2002):

This ecological site occurs throughout the Central Dissected Till Plains Section, particularly in the Grand River Hills Subsection.

Ecological site concept

Loess Upland Prairies are widespread in the uplands of the MLRA, typically upslope from till ecological sites. Soils are very deep, with no rooting restrictions. The reference plant community is prairie dominated by Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), big bluestem, little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and prairie dropseed, with a wide variety of prairie wildflowers.

Associated sites

| R109XY001MO |

Claypan Summit Prairie Claypan Summit Prairie sites are upslope in places, on broad, level divides. |

|---|---|

| R109XY006MO |

Till Upland Prairie Till Upland Prairies are downslope in places, on lower backslopes. |

| R109XY029MO |

Wet Upland Drainageway Prairie Wet Upland Drainageway Prairies are downslope, in drainageways. |

| R109XY046MO |

Till Upland Savanna Till Upland Savannas are downslope in places, on lower backslopes. |

Similar sites

| R109XY006MO |

Till Upland Prairie Till Upland Prairie sites occupy landscape positions below Loess Prairies and have little or no loess caps. Reference state species composition is somewhat similar between these two ecological sites, but the Loess Upland Prairie site is more productive. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Amorpha canescens |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Andropogon gerardii |

Physiographic features

This site is on upland summit crests, shoulders and upper backslopes, with slopes of 0 to 20 percent. The site generates runoff to adjacent, downslope ecological sites. This site does not flood.

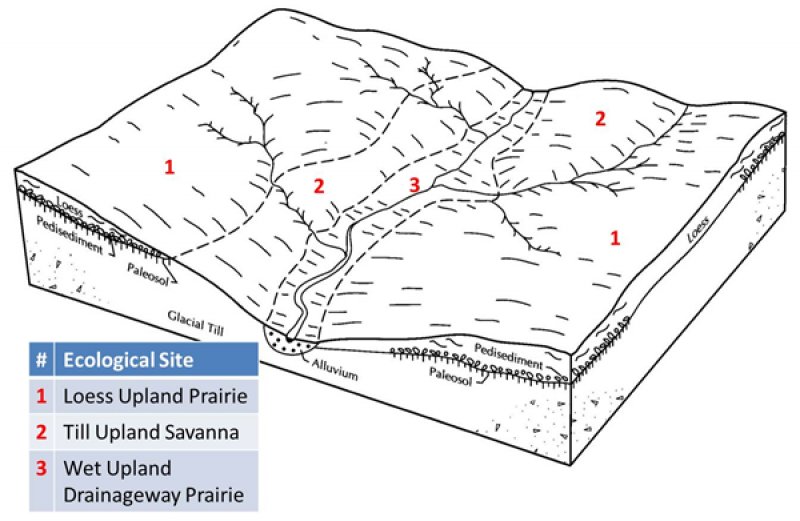

The following figure (adapted from Abney, 1997) shows the typical landscape position of this ecological site, and landscape relationships among the major ecological sites of the uplands. This site is within the area labeled as “1” on the figure, and is typically upslope from Till sites. In some places the site extends downslope to Upland Drainageway sites, as shown in the figure.

Figure 2. Landscape relationships for this ecological site

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Ridge

(2) Interfluve (3) Hill |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 940 – 1,050 ft |

| Slope | 2 – 20% |

| Water table depth | 12 – 48 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The Iowa and Missouri Heavy Till Plain MLRA has a continental type of climate marked by strong seasonality. In winter, dry-cold air masses, unchallenged by any topographic barriers, periodically swing south from the northern plains and Canada. If they invade reasonably humid air, snowfall and rainfall result. In summer, moist, warm air masses, equally unchallenged by topographic barriers, swing north from the Gulf of Mexico and can produce abundant amounts of rain, either by fronts or by convectional processes. In some summers, high pressure stagnates over the region, creating extended droughty periods. Spring and fall are transitional seasons when abrupt changes in temperature and precipitation may occur due to successive, fast-moving fronts separating contrasting air masses.

This MLRA experiences small regional differences in climates that grade inconspicuously into each other. The basic gradient for most climatic characteristics is along a line from north to south. Both mean annual temperature and precipitation exhibit fairly minor gradients along this line.

Mean January minimum temperature follows the north-to-south gradient. However, mean July maximum temperature shows hardly any geographic variation in the region. Mean July maximum temperatures have a range of only two to three degrees across the region.

Mean annual precipitation varies along the same gradient as temperature – lower annual precipitation in the north, higher in the south. Seasonality in precipitation is very pronounced due to strong continental influences. June precipitation, for example, averages four to five times greater than January precipitation.

During years when precipitation comes in a fairly normal manner, moisture is stored in the top layers of the soil during the winter and early spring, when evaporation and transpiration are low. During the summer months the loss of water by evaporation and transpiration is high, and if rainfall fails to occur at frequent intervals, drought will result. Drought directly influences ecological communities by limiting water supplies, especially at times of high temperatures and high evaporation rates. Drought indirectly affects ecological communities by increasing plant and animal susceptibility to the probability and severity of fire. Frequent fires encourage the development of grass/forb dominated communities and understories.

Superimposed upon the basic MLRA climatic patterns are local topographic influences that create topoclimatic, or microclimatic variations. For example, air drainage at nighttime may produce temperatures several degrees lower in valley bottoms than on side slopes. At critical times during the year, this phenomenon may produce later spring or earlier fall freezes in valley bottoms. Slope orientation is an important topographic influence on climate. Summits and south-and-west-facing slopes are regularly warmer and drier, supporting more grass dominated communities than adjacent north- and-east-facing slopes that are cooler and moister that support more woody dominated communities. Finally, the cooler microclimate within a canopied forest is measurably different from the climate of a more open and warmer grassland or savanna area.

Source: University of Missouri Climate Center - http://climate.missouri.edu/climate.php; Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin, United States Department of Agriculture Handbook 296 - http://soils.usda.gov/survey/geography/mlra/

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 137-151 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 167-180 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 39-41 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 133-159 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 167-185 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 38-41 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 144 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 174 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 40 in |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 6. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 7. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 8. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) OSCEOLA [USC00136316], Osceola, IA

-

(2) KEOSAUQUA [USC00134389], Keosauqua, IA

-

(3) UNIONVILLE [USC00238523], Unionville, MO

-

(4) CHILLICOTHE 2S [USC00231580], Chillicothe, MO

Influencing water features

The water features of this upland ecological site include evapotranspiration, surface runoff, and drainage. Many areas of this ecological site are influenced by a seasonal high water table, perched on the subsoil or on underlying till or residuum. Seeps may occur in headslope positions, particularly in the spring and following heavy rainfall events. These seeps are source areas for first-order ephemeral streams, typically within Upland Drainageway ecological sites downslope. Where present, these headslope seeps are in the SLOPE wetlands class of the Hydrogeomorphic (HGM) classification system (Brinson, 1993). Each water balance component fluctuates to varying extents from year-to-year. Conversion to cropland or other high intensities land uses tends to increase runoff, but also decreases evapotranspiration. Depending on the situation, this might increase groundwater discharge, and decrease baseflow in receiving streams.

Soil features

These soils have no major rooting restriction. The soils were formed under prairie vegetation, and have dark, organic-rich surface horizons. Parent material is loess. Some soils are underlain by pedisediment or shale residuum. The soils have silt loam surface horizons. Subsoils are silty clay loam to silty clay. Some soils are affected by seasonal wetness in spring months. Soil series associated with this site include Arispe, Bevier, Chillicothe, Greenton, Grundy, Herrick, Ladoga, Lagonda, Lineville, Pering, Pershing, Seymour, Sharpsburg, Smileyville, and Sturges.

The accompanying picture of the Sharpsburg series shows a dark, organic-rich silt loam surface horizon interfingering into the silty clay loam subsoil at about 15 inches (38 centimeters). Indicators of seasonal wetness (redoximorphic features) are visible in the lower subsoil, but wetness does not impact the diverse, productive tallgrass prairie reference community for this ecological site. Picture from Young (1994); scale is in inches.

Figure 9. Sharpsburg series

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Loess

(2) Till |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Silt loam (2) Silty clay loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Clayey |

| Drainage class | Somewhat poorly drained to moderately well drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow to slow |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

6 – 8 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

4.5 – 7.3 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

Information contained in this section was developed using historical data, professional experience, field reviews, and scientific studies. The information is representative of very complex vegetation communities. Not all scenarios or plants are included or discussed. Key indicator plants, animals and ecological processes are described to help guide land management decisions. Plant communities will differ across the MLRA because of the naturally occurring variability in weather, soils, and aspect. The Reference Plant Community is not necessarily the management goal. The biological processes on this site are complex. Therefore, representative values are presented in a land management context. The species lists are representative and are not botanical descriptions of all species occurring, or potentially occurring, on this site. They are not intended to cover every situation or the full range of conditions, species, and responses for the site.

Loess upland prairies are natural communities dominated by perennial grasses and forbs with scattered shrubs. Patches and mosaic patterns of shrubs co-existed as shown in historical accounts and land surveyor records (Nelson 2010). The prairies of Missouri are considered “tall grass” prairies, an ecosystem indigenous to central North America, because native warm season grasses (6 to 8 feet tall) dominate the rolling uplands common to this region (Kline 1997).

Today’s tall grass prairies developed during the current interglacial period (beginning over 10,000 years ago) when the climate experience a long drying period (King 1981). This area expanded later when warmer, drier conditions continued and fires set by Native Americans increased in frequency and intensity as their populations increased. Missouri’s grasslands were part of this larger tall grass expansion.

Prairie vegetation has adapted to these environmental disturbance pressure through a number of mechanisms. The growing points of grasses occur just below the ground level, which allows grasses to recover after a fire or grazing. Native warm season grasses are also more water efficient because of a different photosynthetic pathway than cool season grasses and long, deep root systems allow these grasses to access lower subsoil moisture areas. (Weaver 1954).

The reference community, a Loess Upland Prairie, is characterized as a tallgrass prairie unit dominated by big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis), and a wide variety of prairie forbs. On lower slopes and draws where water periodically accumulates, more mesic prairie species such as switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), eastern gamagrass (Tripsacum dactyloides), Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum), Michigan lily (Lilium michiganense), and Virginia bunchflower (Veratrum virginicum) are added to the diverse mix of prairie species. (Nelson 2010)

These prairies were typically high in the landscape, dry and fire prone, consequently, this ecological site burned every 1 to 3 years (Anderson 1990). These fires played an important part in managing this habitat. Fire removed dead plant litter and provided room for a lush growth of prairie vegetation. Fire also kept woody species at bay. (Pyne 1984). Grazing by native large herbivores, such as bison (Bison bison), elk (Cervus canadensis), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), also impacted these sites. Their activities altered the composition, fuel loads and structure of the vegetation, creating a diversity of communities and composition (Schroeder 1981). The partially wooded draws would have burned less intensely and less frequently. During fire free intervals woody species would have increased in abundance and spread out onto the prairie.

This type of reference site is very productive. Finding these prairie soils outstanding for crop production, early settlers plowed the prairie everywhere they could for the production of wheat, corn, and other domestic crops. Today because of these activities, Loess Upland Prairies are nearly extirpated from the region. Missouri’s prairies once covered roughly 15 million acre (Schroeder, 1981). Today less than 70,000 acres of all types of prairies still remain (Davit 1999). A few known Loess Upland Prairie remnants exist but most are degraded by fire suppression and grazing by domestic livestock. Other threats include habitat fragmentation, aggressive invasive species, and urban development. While planting prairie on former prairie sites is beneficial to wildlife, restoration to the reference state from agricultural land is a long term proposition with uncertain outcomes.

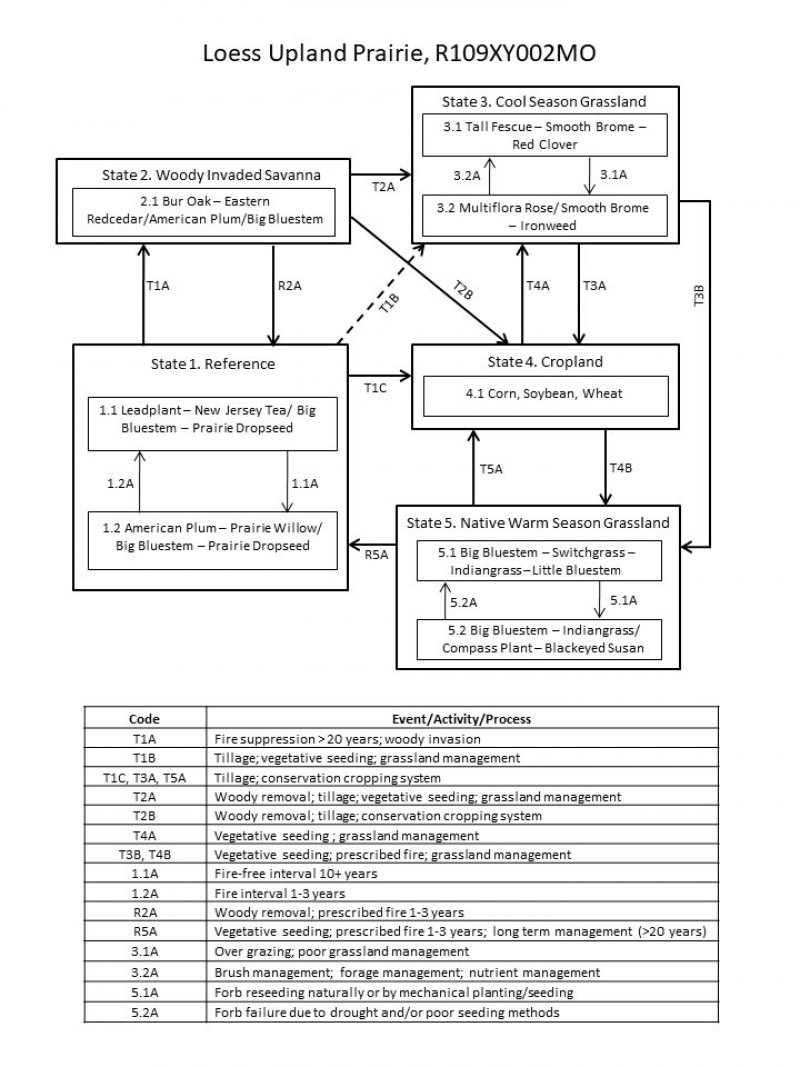

A state and transition model diagram for the Loess Upland Prairie Ecological Site (R109XY002MO) follows this narrative. The following diagram suggests some pathways that the vegetation on this site might take. There may be other states not shown on the diagram. This information is intended to show what might happen in a given set of circumstances. It does not mean that this would happen the same way in every instance. Experts base this model on available experimental research, field observations, professional consensus, and interpretations. It is likely to change as knowledge increases. Local professional guidance should always be sought before pursuing a treatment scenario.

State and transition model

Figure 10. State and transition diagram for this ecological site

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

States 1 and 5 (additional transitions)

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference

This State is native tall grass prairie dominated by prairie dropseed, big bluestem and a wide variety of prairie wildflowers. This State occurs on level to gently sloping soils. In some cases, bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa), swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor), elm (Ulmus sp.), gray dogwood (Cornus racemosa), prairie willow (Salix humilis) and wild plum (Prunus americana) occurred in small groves or as scattered individuals across the prairie landscape. Two phases can occur that will transition back and forth depending on fire frequencies. Longer fire free intervals will allow woody species to increase such as prairie willow, dogwoods and wild plum. When fire intervals shorten these woody species will decrease. This state is rare. Most sites have been converted to cool season grassland and intensive agriculture cropland.

Dominant plant species

-

leadplant (Amorpha canescens), shrub

-

New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), shrub

-

American plum (Prunus americana), shrub

-

prairie willow (Salix humilis), shrub

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), other herbaceous

-

prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis), other herbaceous

Community 1.1

Lead Plant – New Jersey Tea/ Big Bluestem – Prairie Dropseed

Figure 11. Loess Upland Prairie - Helton Prairie Missouri; photo credit Fred Young, NRCS

Figure 12. Loess Upland Prairie - Helton Prairie Conservation Area; photo credit NRCS

This phase has scattered lead plant, New Jersey tea, and prairie willow with grasses such as big bluestem, Indian grass and dropseeds dominating the ground layer. Numerous forbs such as blazing star (Liatris sp.), coneflower (Echinacea sp.), prairie clovers (Dalea sp.), bunchflower, rosinweed (Silphium integrifolium), and compass plant (Silphium laciniatum) are also present and locally abundant. Fire frequencies of 1 to 3 years helped maintain the community structure and composition.

Forest understory. The following "Understory plant type" list is based on reconnaissance-level plots, inventory plots, as well as commonly occurring species listed in Nelson (2010). Species identified from plot data include cover percentages and canopy heights. Species not found in plots, but tallied from "out of plot" surveys near plots surveys show cover estimated percentages. Species not found in plots, but listed in Nelson, do not include cover and canopy data. Note that plot data for canopy heights are by height class, not actual species heights.

Dominant plant species

-

leadplant (Amorpha canescens), shrub

-

New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), shrub

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), other herbaceous

-

prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis), other herbaceous

Figure 13. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forb | 1230 | 3258 | 5285 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 2370 | 2675 | 2980 |

| Shrub/Vine | 0 | 15 | 25 |

| Total | 3600 | 5948 | 8290 |

Table 6. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 0.1-1.0% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 10-50% |

| Forb foliar cover | 2-25% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 25-95% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 1-50% |

Table 7. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (ft) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | – | – | – | – |

| >0.5 <= 1 | 0% | 0-1% | 25-75% | 25-59% |

| >1 <= 2 | 0% | 0-1% | 25-75% | 10-50% |

| >2 <= 4.5 | – | 0-1% | 25-50% | 10-50% |

| >4.5 <= 13 | – | – | – | – |

| >13 <= 40 | – | – | – | – |

| >40 <= 80 | – | – | – | – |

| >80 <= 120 | – | – | – | – |

| >120 | – | – | – | – |

Community 1.2

Wild Plum – Prairie Willow/ Big Bluestem – Prairie Dropseed

Figure 14. Prairie willow invading a Loess Upland Prairie; photo credit - Fred Young, NRCS

This phase is similar to community phase 1.1 but numerous shrubs are increasing due to longer periods of fire suppression. Some displacement of grasses and forbs may be occurring due to shading and competition from the increased densities of shrubs.

Dominant plant species

-

American plum (Prunus americana), shrub

-

prairie willow (Salix humilis), shrub

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), other herbaceous

-

prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis), other herbaceous

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

This pathway results from fire suppression. With fire-free intervals of 10 to 20 years, woody species will increase in density and cover causing the community to gradually shift to phase 1.2 Some displacement of grasses and forbs may be occurring due to shading, competition from the increased densities of shrubs, and increased thatch build up.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

With increased fire frequencies, woody species will decrease in density and cover and over time this community will gradually shift back to community phase 1.1.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning |

|---|

State 2

Woody Invaded Savanna

Degraded reference state that has experienced fire suppression for 20 or more years will transition to this state. With fire suppression, woody species such as bur oak and eastern redcedar will begin to increase transitioning this state from a prairie to a Woody Invaded Savanna. Native ground cover will also decrease and invasive species such as tall fescue may begin to dominate. This state is uncommon due land use conversion within the last century. Historically, transition from this state to cool season grasslands (State 3) or intensive cropland (State 4) was very common.

Dominant plant species

-

bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa), tree

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

-

American plum (Prunus americana), shrub

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), other herbaceous

Community 2.1

Bur Oak – Eastern Redcedar/Wild Plum/Big Bluestem

Figure 15. Degraded loess upland prairie with invading oaks in north-central Misssouri (Photo credit - NRCS)

This phase is the result of prolonged fire suppression. With longer fire intervals woody species such as bur oak, single oak, and eastern redcedar, along with other shrubs, have developed and begun to form a tree canopy. Because of this native grass and forb densities are reduced.

State 3

Cool Season Grassland

Conversion of other states to non-native cool season species such as tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus), smooth brome (Bromus inermis) and red clover (Trifolium pretense) has been common in this area. Occasionally, these grasslands will have scattered bur oaks. This state is typically grazed or used for hay land. Long term uncontrolled grazing and a lack of grassland management can cause significant soil erosion and compaction and increases in less productive species such as multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis) and weedy forbs. A return to the reference state may be impossible, requiring a very long term series of management options.

Dominant plant species

-

multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), shrub

-

tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus), other herbaceous

-

smooth brome (Bromus inermis), other herbaceous

-

red clover (Trifolium pratense), other herbaceous

-

ironweed (Cyanthillium), other herbaceous

Community 3.1

Tall Fescue - Smooth Brome - Red Clover

Figure 16. Tall fesuce dominated grassland under good management; photo credit - Doug Wallace, NRCS

This phase is a well-managed grassland, composed of non-native cool season grasses and legumes. Grazing and haying is occurring. The effects of long-term liming on soil pH, and calcium and magnesium content, is most evident in this phase. Studies show (Conant and others, 2001; Schellberg, and others, 1999) that these soils have higher pH and higher base status in soil horizons as much as two feet below the surface, relative to poorly managed grassland (phase 3.2).

Dominant plant species

-

tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus), other herbaceous

-

smooth brome (Bromus inermis), other herbaceous

-

red clover (Trifolium pratense), other herbaceous

Community 3.2

Multiflora Rose/ Smooth Brome – Ironweed

Figure 17. Weedy cool season grassland; photo credit - Doug Wallace, NRCS

This phase is experiencing woody and weedy forb invasion due to poor management, lack of fertilization and over use.

Dominant plant species

-

multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), shrub

-

smooth brome (Bromus inermis), other herbaceous

-

ironweed (Cyanthillium), other herbaceous

Pathway 3.1A

Community 3.1 to 3.2

This pathway results from extended poor management and over use. After 5 to 10 years legumes will disappear and weedier species such as multiflora rose and ironweed (Vernonia spp.) will increase.

Pathway 3.2A

Community 3.2 to 3.1

This pathway results from improved forage and livestock management and brush removal causing a shift to phase 1.1.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Forage Harvest Management | |

| Forage and Biomass Planting | |

| Nutrient Management | |

| Integrated Pest Management (IPM) | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 4

Cropland

This is the dominant state that exists currently with intensive cropping of corn (Zea mays), soybeans (Glycine max), and wheat (Triticum aestivum) occurring. Some conversion to cool season grassland occurs for a limited period of time before transitioning back to cropland.

Community 4.1

Corn, Soybean, Wheat

Figure 18. Soybeans on loess upland ecological site near Bethany, Missouiri (Photo credit - Doug Wallace)

This phase is due to a land use conversion to intensive agriculture. Principal crops are corn, soybeans, and wheat.

State 5

Native Warm Season Grassland

Conversion from the Cool Season Grassland (State 3) or the Cropland (State 4) to this State is increasing due to renewed interest in warm season grasses as a supplement to cool season grazing systems or as a native restoration activity. Two phases exist. Phase 1 is generally a native grass dominated phase with few to no forbs. Phase 2 sees an increase in forb numbers and diversity due natural invasion and/or mechanical planting and seeding. Phase 2 will transition back to phase 1 through drought, seeding failure, or poor fire management. This State is the most easily transformable state back to a Reference State. Substantial restoration time and management inputs will still be needed.

Dominant plant species

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), grass

-

switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium), grass

-

compassplant (Silphium laciniatum), grass

-

blackeyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), grass

Community 5.1

Big Bluestem - Switchgrass - Indiangrass - Little Bluestem

Figure 19. Re-established native grasses at Dunn Ranch, near Hatfield, Missouri; photo credit - Doug Wallace

This phase, generally through re-establishment, is a native grassland phase dominated by native grasses such as big bluestem and Indian grass. Forbs are seldom present.

Dominant plant species

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), other herbaceous

-

switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), other herbaceous

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum), other herbaceous

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium), other herbaceous

Community 5.2

Big Bluestem – Indiangrass/ Compass Plant – Brown-eyed Susan

Figure 20. Re-established warm season grassland with native forbs added to the planting; photo credit - NRCS

This phase is the result of adding forbs through active reseeding/planting and/or natural encroachment. This phase can also occurring if natural re-establishment is dominated by forbs or if the artificial reseeding in phase 5.1 experiences partial or extensive grass failure.

Dominant plant species

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), other herbaceous

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum), other herbaceous

-

compassplant (Silphium laciniatum), other herbaceous

-

blackeyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), other herbaceous

Pathway 5.1A

Community 5.1 to 5.2

Forb reseeding naturally or by mechanical planting/seeding

Pathway 5.2A

Community 5.2 to 5.1

Forb failure due to drought and/or poor seeding methods

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Fire suppression activities for greater than 20 years and woody invasion will result in a transition to community phase 2.1.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Destroying the prairie sod with tillage, adding a cool season grass/legume vegetative seeding and grassland management will result in a transition to community phase 3.1.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

Removing the prairie sod with tillage and adding a conservation cropping system will result in a transition to community phase 4.1.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

This state can be restored to a reference state with woody removal, brush management, planting additional native grass and forb species and initiating a prescribe fire regime (every 1 to 3 years). Limited controlled grazing may also be needed.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Woody removal, brush control, removing the prairie sod with tillage seeding cool season grass and legume species and incorporating grassland management will result in a transition to community phase 3.1.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

Woody removal, brush control, removing the prairie sod with tillage and incorporating conservation cropping system will result in a transition to community phase 4.1.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Removing the cool season sod with tillage and adding a conservation cropping system will result in a transition to community phase 4.1.

Transition T3B

State 3 to 5

Killing the existing cool season sod, reseeding to native warm season grasses and adding prescribed fire will result in a transition to community phase 5.1.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 3

A seeding of cool season grasses and legumes and grassland management will result in a transition to community 3.1.

Transition T4B

State 4 to 5

A seeding of native warm season grasses and grassland management will result in a transition to community 3.1.

Restoration pathway R5A

State 5 to 1

This state can be restored to a reference state by planting additional native grass and forb species and initiating a prescribe fire regime (every 1 to 3 years). Limited controlled grazing may also be needed.

Transition T5A

State 5 to 4

Removing the warm season grass sod, adding seasonal tillage and a conservation cropping system will result in a transition to community 3.1.

Additional community tables

Table 8. Community 1.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| prairie dropseed | SPHE | Sporobolus heterolepis | Native | 0.3–1 | 25–50 | |

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | Native | 0.3–7 | 5–50 | |

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | Native | 0.3–7 | 10–50 | |

| bluejoint | CACA4 | Calamagrostis canadensis | Native | – | 0–1 | |

| flatstem spikerush | ELCO2 | Eleocharis compressa | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| Canada wildrye | ELCA4 | Elymus canadensis | Native | – | 0–1 | |

| whip nutrush | SCTR | Scleria triglomerata | Native | 0.3–1 | 0.1 | |

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | Native | – | – | |

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | Native | – | – | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| rough false pennyroyal | HEHI | Hedeoma hispida | Native | 0.3–7 | 0.1–25 | |

| Canada goldenrod | SOCA6 | Solidago canadensis | Native | 0.3–7 | 0.1–10 | |

| western rough goldenrod | SORA | Solidago radula | Native | 0.3–7 | 0.1–10 | |

| roundhead lespedeza | LECA8 | Lespedeza capitata | Native | 0.3–4.5 | 0.1–10 | |

| wholeleaf rosinweed | SIIN2 | Silphium integrifolium | Native | 0.3–7 | 0.1–10 | |

| showy ticktrefoil | DECA7 | Desmodium canadense | Native | – | 0.1–10 | |

| sawtooth sunflower | HEGR4 | Helianthus grosseserratus | Native | – | 1–5 | |

| stiff sunflower | HEPA19 | Helianthus pauciflorus | Native | – | 2–5 | |

| white crownbeard | VEVI3 | Verbesina virginica | Native | 0.3–2 | 2–5 | |

| white heath aster | SYER | Symphyotrichum ericoides | Native | 0.3–1 | 1–2 | |

| stiff goldenrod | OLRI | Oligoneuron rigidum | Native | – | 1–2 | |

| partridge pea | CHFA2 | Chamaecrista fasciculata | Native | – | 0.1–2 | |

| Texas goldentop | EUGY | Euthamia gymnospermoides | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| downy phlox | PHPI | Phlox pilosa | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| common cinquefoil | POSI2 | Potentilla simplex | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| hemlock waterparsnip | SISU2 | Sium suave | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| giant goldenrod | SOGI | Solidago gigantea | Native | – | 0–1 | |

| Richardson's alumroot | HERI | Heuchera richardsonii | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| bluejacket | TROH | Tradescantia ohiensis | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| golden zizia | ZIAU | Zizia aurea | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| New England aster | SYNO2 | Symphyotrichum novae-angliae | Native | 0.3–2 | 0.1–1 | |

| sessileleaf ticktrefoil | DESE | Desmodium sessilifolium | Native | 0.3–2 | 0.1–1 | |

| flowering spurge | EUCO10 | Euphorbia corollata | Native | 0.3–2 | 0.1–1 | |

| compassplant | SILA3 | Silphium laciniatum | Native | 0.3–1 | 0.1–1 | |

| Gattinger's goldenrod | SOGA | Solidago gattingeri | Native | 0.3–2 | 0.1–1 | |

| wild quinine | PAIN3 | Parthenium integrifolium | Native | 0.3–1 | 0.1–1 | |

| tall tickseed | COTR4 | Coreopsis tripteris | Native | 0.3–7 | 0.1–1 | |

| white prairie clover | DACA7 | Dalea candida | Native | 0.3–1 | 0.1 | |

| purple prairie clover | DAPU5 | Dalea purpurea | Native | 0.3–1 | 0.1 | |

| narrowleaf mountainmint | PYTE | Pycnanthemum tenuifolium | Native | 0.3–1 | 0.1 | |

| pinnate prairie coneflower | RAPI | Ratibida pinnata | Native | 0.3–2 | 0.1 | |

| American alumroot | HEAM6 | Heuchera americana | Native | 0.3–0.5 | 0.1 | |

| American hogpeanut | AMBR2 | Amphicarpaea bracteata | Native | 0.3–1 | 0.1 | |

| white wild indigo | BAAL | Baptisia alba | Native | 0.3–2 | 0.1 | |

| longbract wild indigo | BABR2 | Baptisia bracteata | Native | 0.3–0.5 | 0.1 | |

| Virginia strawberry | FRVI | Fragaria virginiana | Native | 0.3–0.5 | 0.1 | |

| stiff marsh bedstraw | GATI | Galium tinctorium | Native | 0.3–0.5 | 0.1 | |

| prairie blazing star | LIPY | Liatris pycnostachya | Native | 0.3–2 | 0.1 | |

| Baldwin's ironweed | VEBA | Vernonia baldwinii | Native | 0.3–2 | 0.1 | |

| stiff tickseed | COPA10 | Coreopsis palmata | Native | – | 0–0.1 | |

| Culver's root | VEVI4 | Veronicastrum virginicum | Native | – | – | |

| Virginia bunchflower | VEVI5 | Veratrum virginicum | Native | – | – | |

| eastern purple coneflower | ECPU | Echinacea purpurea | Native | – | – | |

| button eryngo | ERYU | Eryngium yuccifolium | Native | – | – | |

| ashy sunflower | HEMO2 | Helianthus mollis | Native | – | – | |

| hoary puccoon | LICA12 | Lithospermum canescens | Native | – | – | |

| wild bergamot | MOFI | Monarda fistulosa | Native | – | – | |

| purple milkwort | POSA3 | Polygala sanguinea | Native | – | – | |

| prairie milkweed | ASSU3 | Asclepias sullivantii | Native | – | – | |

| butterfly milkweed | ASTU | Asclepias tuberosa | Native | – | – | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| gray dogwood | CORA6 | Cornus racemosa | Native | – | 0.1–1 | |

| leadplant | AMCA6 | Amorpha canescens | Native | 0.3–2 | 0.1–1 | |

| northern dewberry | RUFL | Rubus flagellaris | Native | 0.3–0.5 | 0.1 | |

| spotted St. Johnswort | HYPU | Hypericum punctatum | Native | – | 0–0.1 | |

| Carolina rose | ROCA4 | Rosa carolina | Native | 0.3–0.5 | 0.1 | |

| New Jersey tea | CEAM | Ceanothus americanus | Native | – | – | |

| American plum | PRAM | Prunus americana | Native | – | – | |

| prairie willow | SAHU2 | Salix humilis | Native | – | – | |

| false indigo bush | AMFR | Amorpha fruticosa | Native | – | – | |

Interpretations

Animal community

Wildlife

Game species that utilize this ecological site include: Northern Bobwhite will utilize this ecological site for food (seeds, insects) and cover needs (escape, nesting and roosting cover).

Cottontail rabbits will utilize this ecological site for food (seeds, soft mast) and cover needs.

Turkey will utilize this ecological site for food (seeds, green browse, soft mast, insects) and nesting and brood-rearing cover. Turkey poults feed heavily on insects provided by this site type.

White-tailed Deer will utilize this ecological site for browse (plant leaves in the growing season, seeds and soft mast in the fall/winter). This site type also can provide escape cover.

Bird species associated with this ecological site’s reference state condition (Jacobs 2001): Breeding birds as related to vegetation structure (related to time since fire, grazing, haying, and mowing):

Vegetation Height Short ( 0.5 meter, low litter levels, bare ground visible): Grasshopper Sparrow, Horned Lark, Upland Sandpiper, Greater Prairie Chicken, Northern Bobwhite

Mid-Vegetation Height (0.5 – 1 meter, moderate litter levels, some bare ground visible): Eastern Meadowlark, Dickcissel, Field Sparrow, Upland Sandpiper, Greater Prairie Chicken, Northern Bobwhite, Eastern Kingbird, Bobolink, Lark Sparrow

Tall Vegetation Height (> 1 meter, moderate-high litter levels, little bare ground visible): Henslow’s Sparrow, Dickcissel, Greater Prairie Chicken, Field Sparrow, Northern Bobwhite, Sedge Wren, Northern Harrier

Brushy – Mix of grasses, forbs, native shrubs (e.g., Rhus copallina, Prunus americana, Rubus spp., Rosa carolina) and small trees (e.g., Cornus racemosa): Bell’s Vireo, Yellow-Breasted Chat, Loggerhead Shrike, Brown Thrasher, Common Yellowthroat

Winter Resident: Short-Eared Owl, Le Conte’s Sparrow.

Amphibian and reptile species associated with this ecological site’s reference state condition: prairies with or nearby to fishless ponds/pools (may be ephemeral) may have Eastern Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum tigrinum) and Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris triseriata triseriata); prairies with crawfish burrows may have Northern Crawfish Frog (Rana areolata circulosa); other species include Northern Prairie Skink (Eumeces septentrionalis septentrionalis), Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata ornata), Western Slender Glass Lizard (Ophisaurus attenuatus attenuatus), Eastern Yellow-bellied Racer (Coluber constrictor flaviventris), Prairie Ring-necked Snake (Diadophis punctatus arnyi), and Bullsnake (Pituophis catenifer sayi).

Small mammals associated with this ecological site’s reference state condition: Least Shrew (Cryptotis parva), Franklin’s Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus franklinii), Plains Pocket Gopher (Geomys bursarius), Prairie Vole (Microtus ochrogaster), Southern Bog Lemming (Synaptomys cooperi), Meadow Jumping Mouse (Zapus hudsonius), Thirteen-lined Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus) and Badger (Taxidea taxus).

Invertebrates: Many native insect species are likely associated with this ecological site, especially native bees, ants, beetles, butterflies and moths, and crickets, grasshoppers and katydids. However information on these groups is often lacking enough resolution to assign them to individual ecological sites.

Insect species known to be associated with this ecological site’s reference state condition: Regal Fritillary butterfly (Speyeria idalia) whose larvae feed primarily on native prairie violets (Viola pedata, V. pedatifida, and V. sagittata); Mottled Dusky Wing butterfly (Erynnis martialis), Golden Byssus butterfly (Problema byssus kumskaka), Delaware Skipper butterfly (Atryone logan logan), and Crossline Skipper butterfly (Polites origenes). The larvae of the moth Eucosma bipunctella bore into compass plant (Silphium laciniatum) roots and feed and the larvae of the moth Eucosma giganteana bore into a number of Silphium species roots and feed. Native bees, important pollinators, that may be associated with this ecological site’s reference condition include: Colletes brevicornis, Andrena beameri, A. helianthiformis, Protandrena rudbeckiae, Halictus parallelus, Lasioglossum albipennis, L. coreopsis, L. disparilis, L. nymphaereum, Ashmeadiella bucconis, Megachile addenda, Anthidium psoraleae, Eucera hamata, Melissodes coloradensis, M. coreopsis, and M. vernoniae. The Short-winged Katydid (Amblycorypha parvipennis), Green Grasshopper (Hesperotettix speciosus) and Two-voiced Conehead katydid (Neoconcephalus bivocatus) are possible orthopteran associates of this ecological site.

Other invertebrate associates include the Grassland Crayfish (Procambarus gracilis).

(This section developed by Mike Leahy, Natural Areas Coordinator, Missouri Department of Conservation, 2013; references for this section include: Easterla, 1962; Fitzgerald and Pashley. 2000b; Heitzman and Heitzman 1996; Jacobs 2001; Johnson 2000; Pitts and McGuire 2000; Schwartz and others 2001)

Recreational uses

Hunting, bird watching, horseback riding, camping, and hiking are recreational uses of the reference state and the native warm season grassland state. Reference and well managed sites provide good hunting for quail, rabbits, and other small mammals. Recreational uses are reduced in the heavily grazed grassland state and cropland state. In many areas of this predominantly agricultural MLRA, these sites provide the only open grasslands available for recreational use.

Other information

Forestry

Management: This ecological site is not recommended for traditional timber management activity. Historically this site was dominated by a ground cover of native prairie grasses and forbs. Some scattered open grown trees may have also been present.

This site may be suitable for non-traditional forestry uses such as windbreaks, environmental plantings, alley cropping (a method of planting, in which rows of trees or shrubs are interspersed with rows of crops) or woody bio-fuels.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Potential Reference Sites for Loess Upland Prairie

Plot MOPRCA01 – Ladoga soil

Morris Prairie CA, Sullivan County, MO

Latitude: 40.38487

Longitude: -92.94362

Plot HEPRCA01 – Lagonda soil

Helton Prairie CA, Harrison County, MO

Latitude: 40.25651

Longitude: -93.83319

Type locality

| Location 1: Sullivan County, MO | |

|---|---|

| Township/Range/Section | T64N R18W S5 |

| UTM zone | N |

| UTM northing | 4470476.97 |

| UTM easting | 504785.452 |

| Latitude | 40° 23′ 5″ |

| Longitude | -92° 56′ 37″ |

| General legal description | Plot MOPRCA01; Morris Prairie Cons Area; Ladoga soil. |

| Location 2: Harrison County, MO | |

| Township/Range/Section | T63N R26W S16 |

| UTM zone | N |

| UTM northing | 4456560.87 |

| UTM easting | 429145.57 |

| Latitude | 40° 15′ 23″ |

| Longitude | -93° 49′ 59″ |

| General legal description | Plot HEPRCA01; Helton Prairie Cons Area; Lagonda soil. |

Other references

Abney, Mark A. 1997. Soil Survey of Chariton County, Missouri. U.S. Dept. of Agric. Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Anderson, R.C. 1990. The historic role of fire in North American grasslands. Pgs.8-18 in “Fire in North American tallgrass prairies.” University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Brinson, M.M. 1993. A hydrogeomorphic classification for wetlands. Technical Report WRP-DE-4, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Waterways Experiment Station, Vicksburg, MS.

Davit, C.E. (ed.). 1999. Public prairies of Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Fitzgerald, J.A. and D.N. Pashley. 2000a. Partners in Flight bird conservation plan for the Ozark/Ouachitas. American Bird Conservancy.

Fitzgerald, J.A. and D.N. Pashley. 2000b. Partners in Flight bird conservation plan for the Dissected Till Plains. American Bird Conservancy.

Heitzman, J.R. and J.E. Heitzman. 1996. Butterflies and moths of Missouri. 2nd ed. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City.

Jacobs, B. 2001. Birds in Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City.

Johnson, T.R. 2000. The amphibians and reptiles of Missouri. 2nd ed. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City.

Kline, V. 1997. Orchards of oak and a sea of grass. The tallgrass restoration handbook for prairies, savannas, and woodlands. Society for Ecological Restoration. Island Press, Washington, D.C.

King, J.E. 1981. Late Quaternary vegetational history of Illinois. Ecological Monographs 512:43-62

NatureServe, 2010. Vegetation Associations of Missouri (revised). NatureServe, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Nelson, Paul W. 2010. The Terrestrial Natural Communities of Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Nigh, Timothy A. and Walter A. Schroeder. 2002. Atlas of Missouri Ecoregions. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Pitts, D.E. and W.D. McGuire. 2000. Wildlife management for Missouri landowners. 3rd ed. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City.

Pyne, S.J. 1984. Introduction to wildland fire and fire management in the United States. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York.

Schroeder, W.A. 1981. Presettlement prairie of Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Natural History Series No. 2. Jefferson City.

Schwartz, C.W., E.R. Schwartz and J.J. Conley. 2001. The wild mammals of Missouri. University of Missouri Press, Columbia and Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City.

United States Department of Agriculture – Natural Resource Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS). 2006. Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbook 296. 682 pps.

Weaver, J.E. 1954. North American Prairie. Johnson Publishing Company, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Young, Fred J. 1994. Soil Survey of Atchison County, Missouri. U.S. Dept. of Agric. Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Contributors

Doug Wallace

Fred Young

Approval

Suzanne Mayne-Kinney, 7/01/2024

Acknowledgments

Missouri Department of Conservation and Missouri Department of Natural Resources personnel provided significant and helpful field and technical support in the development of this ecological site.

This site was originally approved on 07/28/2015 for publication.

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) |

Douglas Wallace NRCS ACES Ecologist |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author |

Parkade Center NRCS 601 Business Loop 70 West Columbia, MO 65203 |

| Date | 07/28/2015 |

| Approved by | Suzanne Mayne-Kinney |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Foliar Cover |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

Rills are rare due to the extensive ground cover and thatch build up. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Water flows in interstitial areas between grass and forb hummocks. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

rare; < 1 inch in height -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Bare ground areas are rare in unburned areas. Bare ground occurs immediately after prescribed burns that remove significant amounts of plant material. Within a few months after the burn the site is recovered. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

none -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

none -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

minimal -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil surface resistance to erosion is strong due the high amounts of ground cover and extensive root systems. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

0-12 inches very dark brown; SOM <5% -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

Infiltration is high and runoff is low. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm season grasses > forbs > sedgesSub-dominant:

Other:

shrubsAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

All plant species should be capable of reproduction depending on water availability. All plants should be vigorous, healthy and reproductive depending on disturbance (e.g., drought). Plants should have numerous seed heads, vegetative tillers etc.

The only limitations are weather-related effects, wildfire, and natural disease that may temporarily reduce reproductive capability. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

5932 pounds/acre -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

eastern redcedar, smooth sumac, sweet clover, tall fescue, teasel -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Better in normal to wet years and seasons. Poorer in dry years and seasons.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.