Ecological dynamics

A PROVISIONAL ECOLOGICAL SITE is a conceptual grouping of soil map unit components within a major land resource area (MLRA) based on the similarities in response to management. Although there may be wide variability in the productivity of the soils grouped into a provisional site, the soil vegetation interactions as expressed in the state and transition model are similar and the management actions required to achieve objectives, whether maintaining the existing ecological state or managing for an alternative state, are similar. Provisional sites are likely to be refined into more precise group during the process of meeting the APPROVED ECOLOGICAL SITE DESCRIPTION criteria.

This PROVISIONAL ECOLOGICAL SITE has been developed to meet the standards established in the National Ecological Site Handbook. The information associated with this ecological site does not meet the approved ecological site description standard, but it has been through a quality control and quality assurance processes to ensure consistency and completeness. Further investigations, reviews and correlations are necessary before it becomes an approved ecological site description.

The vegetation groupings described in this section are based on the terrestrial ecological system classification developed by NatureServe (Comer et al. 2003). Ecological systems represent recurring groups of biological communities that are found in similar physical environments and are influenced by similar dynamic ecological processes, such as fire or flooding. They are intended to provide a classification unit that is readily mappable, often from remote imagery, and readily identifiable by conservation and resource managers in the field.

Provisional Ecological Sites are intended to be very broad and should be considered first approximations based on existing available data. This PES covers multiple ecological systems. The ecological system defined by NatureServe that most likely approximates the reference community of this PES across the largest acreage based on spatial analysis is Southern Appalachian Oak Forest.

This (following) information is provided by NatureServe (www.natureserve.org) and its network of natural heritage member programs, a leading source of information about rare and endangered species, and threatened ecosystems.

Southern Appalachian Oak Forest: “These forests are dominated by Quercus species, most typically Quercus alba, Quercus coccinea, Quercus prinus, Quercus rubra, and Quercus velutina with varying amounts of Acer rubrum, Carya spp., Fraxinus americana, Nyssa sylvatica, and other species. Less typical are stands dominated by other hardwood species, or by Pinus strobus. Historically, Castanea dentata was a dominant or codominant in many of these communities until its virtual elimination by the chestnut blight fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) during the early 1900s. Subcanopies and shrub layers are usually well-developed. Some areas (usually on drier sites) now have dense evergreen heath shrub layers of Kalmia latifolia, with Rhododendron maximum on more mesic sites. Some other areas have deciduous heath-dominated layers, sometimes consisting of Vaccinium spp. or Gaylussacia spp. Herbs, forbs and ferns are usually sparse to moderate in density.

Dynamics: This system is naturally dominated by stable, uneven-aged forests. Extreme wind or ice storms occasionally create larger canopy openings. Natural old-growth forest examples have trees reproducing in small to medium-sized canopy gaps created by the death of individual or small groups of trees. Fire occurred fairly frequently in presettlement times, though there is some dispute whether most of the fires were natural or anthropogenic in origin (Abrams 1992, Delcourt and Delcourt 1997). Fires were usually low-intensity surface fires. The dominant species are fairly fire-tolerant, making most fires non-catastrophic. Fire may be important for favoring oak dominance over more mesophytic tree species within some of the topographic range of this system. Fire also can be expected to have a moderate effect on vegetation structure, producing a somewhat more open canopy and less dense understory and shrub layer than currently seen in most examples. Fire frequency or intensity may be important for determining the boundary between this system and both the more mesic and the drier systems. Virtually all examples have been strongly affected by the introduction of the chestnut blight, which killed all of the Castanea dentata trees, eliminating it as a canopy dominant. Past logging affected most occurrences. Regenerated forest canopies are even-aged, or have a more even-aged structure. Extreme wind or ice storms occasionally create larger canopy openings, which may provide particularly good sites for Quercus regeneration. Virtually all examples have been strongly affected by introduction of chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica), which killed Castanea dentata trees, eliminating it as a canopy dominant. The introduction, and now widespread establishment, of gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) that favors oaks as food has also affected these forests by causing widespread mortality of overstory trees depending on topographic position and precipitation amounts around defoliation events. Past logging, and now lack of fire, has affected most occurrences by changing canopies to an even-aged, or more even-aged, structure with an understory of shade-tolerant but fire-intolerant species such as Pinus strobus, Acer rubrum, and Acer pensylvanicum. The removal of Castanea dentata from the overstory of these forests is thought to have benefited Carya spp., and their persistence and continued recruitment in contemporary oak-hickory forests may reflect fire exclusion in recent decades. (This) occurs as a large-patch to matrix system. Contiguous areas of tens of thousands of acres once occurred. The oak forests probably make up slightly more than 50% of the landscape in all but the higher elevations of the region. Size of existing occurrences may be strongly affected by separation distances for occurrences. A few remaining occurrences over 10,000 acres are probably present.”

Description Author: M. Schafale, R. Evans, M. Pyne, R. White, S.C. Gawler Version: 29 Apr 2016

USDA-NRCS OSDs for soils included in this PES largely agree, stating that most of these soils are forested with dominant forest types consisting of northern red oak associated with black cherry, sugar maple, American beech, black oak, black birch, yellow birch, yellow-poplar, eastern hemlock, and black locust. In the drier, warmer part of the range, upland oaks, hickory, blackgum, red maple, and eastern white pine are associated. Flowering dogwood, mountain-laurel, silverbell, striped maple, serviceberry, rhododendron, red maple, blueberry, trillium, Solomons seal, and woodfern are common understory species. A small percent of this soil is cleared and used for pasture, ornamentals, and Christmas trees.

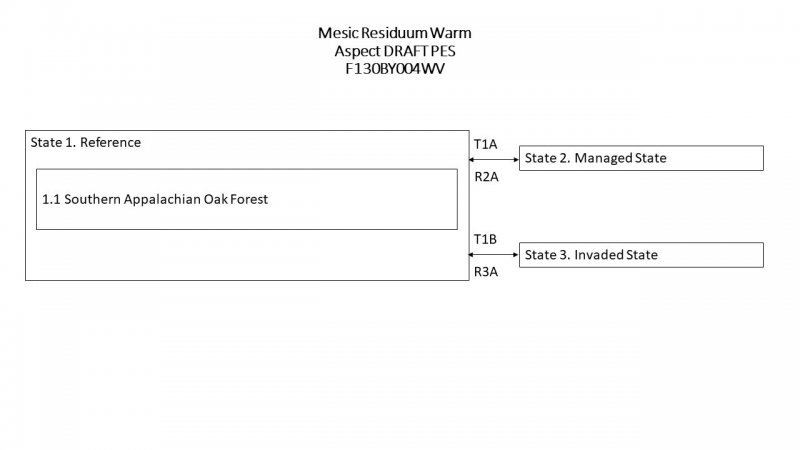

State 1

Reference - Southern Appalachian Oak Forest

The reference state includes one major NatureServe ecological systems as described previously, Southern Appalachian Oak Forest. Oaks now dominate this site where American chestnut once would have been a major species dominant in the canopy. Invasive, non-native forest pests and pathogens such as American chestnut blight, dogwood anthracnose, and European gypsy moth (among others) are really the greatest threat to this PES. Most of it is still currently forested, although a good bit of it has been logged, burned or both in the past.

State 2

Managed State

Because most of this ecological site is publicly owned, very little private management takes place. However, some acreage is in pasture and Christmas tree production. Forestry may be important on National Forests. Further investigation in the field is needed as future projects are identified to refine this PES into what will most likely become multiple ecological sites.

State 3

Invaded State

Perhaps the greatest challenge to the integrity of this ecological site is the presence of invasive, non-native pests and pathogens. The impact and response varies by species (both of the host and the invader) but often will include combinations of mechanical, biological, chemical and cultural control. Tree breeding programs for genetic resistance and germplasm conservation may be important considerations, especially in front an incoming invasion if reforestation is planned after it passes. It is always best if local genetic material can be used if restoration efforts are attempted.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Conversion to pasture or Christmas tree production

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Invasion by a number of non-native forest pests and plants

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Abandonment (~100 years until reversion to forest); control of non-native plants and pests where needed

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 1

Management of invasive species (mechanical, chemical, biological control, etc.)