Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F130BY008WV

Shallow Mesic Residuum

Last updated: 9/07/2018

Accessed: 12/05/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 130B–Southern Blue Ridge

This MLRA is in North Carolina (51 percent), Tennessee (18 percent), Georgia (17 percent), Virginia (10 percent), and South Carolina (4 percent). It makes up about 16,080 square miles (41,665 square kilometers). It is locally known as the Southern Appalachians. It includes Lenoir, Morganton, Marion, Hendersonville, Waynesville, and Asheville, North Carolina; Gatlinburg, Tennessee; Damascus and Galax, Virginia; Walhalla, South Carolina; and Cleveland, Dahlonega, and Ellijay, Georgia. Interstate 40 crosses the parts of the area in Tennessee and North Carolina. Interstate 77 crosses the part in Virginia. Many national forests are in the area, including the Jefferson, Cherokee, Nantahala, Pisgah, and Chattahoochee National Forests. The Appalachian Trail begins on Springer Mountain in Georgia, near Amicalola State Park. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is in this MLRA. The Mount Rogers National Recreation Area is in the part of the MLRA in Virginia. The Cherokee Indian Reservation is west of Waynesville, North Carolina.

Ecological site concept

Practically all of the acreage in this Provisional Ecological Site (PES) is in forest consisting chiefly of chestnut oak, scarlet oak, white oak, Virginia pine, pitch pine, maple, and white pine. However, table mountain pine can occur here. It is considered a high conservation concern as it requires fire (probably a very hot fire) to regenerate. Fire may be an important disturbance on this site (note lower AWC). Further investigations in the field should be prioritized in future projects.

Soils included in this site generally occur between 1,800’ – 4,500’ in elevation and are typically found on mountain summits and side slopes in the southern Blue Ridge mountains.

Forestry and forest health protection would be the chief resource concerns on this site.

Associated sites

| F130BY005WV |

Mesic Colluvium Cool Aspect |

|---|

Similar sites

| F130BY005WV |

Mesic Colluvium Cool Aspect |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

Not specified |

Physiographic features

This MLRA is mainly in the Southern Section of the Blue Ridge Province of the Appalachian Highlands. The southern tip of the MLRA and two protruding areas to the east are in the Piedmont Uplands Section of the Piedmont Province of the Appalachian Highlands. This MLRA consists of several distinct topographic areas, including the Blue Ridge Escarpment on the eastern edge of the area, the New River Plateau on the northern end, interior low and intermediate mountains throughout the MLRA, intermountain basins between the major mountains, and the high mountains making up the bulk of the MLRA. Elevation ranges from about 900 feet (275 meters) at the south and southwest boundaries of the area to more than 6,600 feet (2,010 meters) at the crest of the Great Smoky and Black Mountain ranges.

The extent of the major Hydrologic Unit Areas (identified by four-digit numbers) that make up this MLRA is as follows: Upper Tennessee (0601), 46 percent; Kanawha (0505), 13 percent; Middle Tennessee-Hiwassee (0602), 12 percent; Edisto-Santee (0305), 9 percent; Alabama (0315), 8 percent; Ogeechee-Savannah (0306), 6 percent; Pee Dee (0304), 4 percent; Chowan-Roanoke (0301), 1 percent; and Apalachicola (0313), 1 percent. From north to south, the major rivers in this area are the New River in Virginia; the Yadkin, Catawba, French Broad, Little Tennessee, and Hiwassee Rivers in North Carolina; the Saluda, Seneca, Chattooga, and Tugaloo Rivers in South Carolina; and the Toccoa and Coosawattee Rivers in Georgia. The Tugaloo River is a headwater stream of the Savannah River, and the French Broad, Little Tennessee, Hiwassee, and Ocoee Rivers also flow into Tennessee in this area. The Hiwassee River in Tennessee and the Conasauga River in Georgia have been designated National Wild and Scenic Rivers in this area. The Chattooga River (made famous in the motion picture “Deliverance”) in South Carolina is a National Scenic River.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Mountain

(2) Mountain slope (3) Ridge |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 256 – 1,482 m |

| Slope | 10 – 95% |

| Water table depth | 152 cm |

Climatic features

The average annual precipitation in this area generally is 36 to 60 inches (915 to 1,525 millimeters), generally increasing with elevation. It is 60 to 90 inches (1,525 to 2,285 millimeters) in southwestern North Carolina and northeastern Georgia and can be as much as 119 inches (3,025 millimeters) on the higher peaks in the MLRA. Much of the precipitation occurs as snow at the higher elevations. The amount of precipitation is lowest in the fall. The average annual temperature ranges from 46 to 60 degrees F (8 to 16 degrees C), decreasing with elevation. The freeze-free period averages 185 days and ranges from 135 to 235 days. The freeze-free period is shorter at high elevations and on valley floors because of cold air drainage. Microclimate differences resulting from aspect significantly affect the type and vigor of the plant communities in the area. South- and west-facing slopes are warmer and drier than north- and east-facing slopes and those shaded by the higher mountains.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 162 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 184 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 1,397 mm |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 3. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 4. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) JASPER 1 NNW [USC00094648], Jasper, GA

-

(2) ANDREWS [USC00310184], Andrews, NC

-

(3) BANNER ELK [USC00310506], Banner Elk, NC

-

(4) MARION 2 NW [USC00315340], Marion, NC

-

(5) GALAX RADIO WBRF [USC00443267], Galax, VA

-

(6) BLAIRSVILLE EXP STN [USC00090969], Blairsville, GA

Influencing water features

This ecological site is not influenced by wetland or riparian water features.

Soil features

Soil series occurring in this PES include Sylco, Cataska, Ditney, and Unicoi. This site is on mountain summits and side slopes in the Blue Ridge (MLRA 130). Parent material is residuum that is affected by soil creep in the upper solum.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Creep deposits

–

arkose

(2) Residuum – graywacke |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Channery fine sandy loam (2) Cobbly loam (3) Extremely channery sandy loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained to excessively drained |

| Permeability class | Very rapid |

| Soil depth | 28 – 99 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 30% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0 – 30% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

2.03 – 13.72 cm |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

4.2 – 5.2 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 55% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 70% |

Ecological dynamics

The vegetation groupings described in this section are based on the terrestrial ecological system classification developed by NatureServe (Comer et al. 2003). Ecological systems represent recurring groups of biological communities that are found in similar physical environments and are influenced by similar dynamic ecological processes, such as fire or flooding. They are intended to provide a classification unit that is readily mappable, often from remote imagery, and readily identifiable by conservation and resource managers in the field.

Provisional Ecological Sites are intended to be very broad and should be considered first approximations based on existing available data. This PES covers multiple ecological systems. The ecological system defined by NatureServe that most likely approximates the reference community of this PES across the largest acreage based on spatial analysis is Southern Appalachian Oak Forest.

This (following) information is provided by NatureServe (www.natureserve.org) and its network of natural heritage member programs, a leading source of information about rare and endangered species, and threatened ecosystems.

Southern Appalachian Oak Forest: “These forests are dominated by Quercus species, most typically Quercus alba, Quercus coccinea, Quercus prinus, Quercus rubra, and Quercus velutina with varying amounts of Acer rubrum, Carya spp., Fraxinus americana, Nyssa sylvatica, and other species. Less typical are stands dominated by other hardwood species, or by Pinus strobus. Historically, Castanea dentata was a dominant or codominant in many of these communities until its virtual elimination by the chestnut blight fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) during the early 1900s. Subcanopies and shrub layers are usually well-developed. Some areas (usually on drier sites) now have dense evergreen heath shrub layers of Kalmia latifolia, with Rhododendron maximum on more mesic sites. Some other areas have deciduous heath-dominated layers, sometimes consisting of Vaccinium spp. or Gaylussacia spp. Herbs, forbs and ferns are usually sparse to moderate in density.

Dynamics: This system is naturally dominated by stable, uneven-aged forests. Extreme wind or ice storms occasionally create larger canopy openings. Natural old-growth forest examples have trees reproducing in small to medium-sized canopy gaps created by the death of individual or small groups of trees. Fire occurred fairly frequently in presettlement times, though there is some dispute whether most of the fires were natural or anthropogenic in origin (Abrams 1992, Delcourt and Delcourt 1997). Fires were usually low-intensity surface fires. The dominant species are fairly fire-tolerant, making most fires non-catastrophic. Fire may be important for favoring oak dominance over more mesophytic tree species within some of the topographic range of this system. Fire also can be expected to have a moderate effect on vegetation structure, producing a somewhat more open canopy and less dense understory and shrub layer than currently seen in most examples. Fire frequency or intensity may be important for determining the boundary between this system and both the more mesic and the drier systems. Virtually all examples have been strongly affected by the introduction of the chestnut blight, which killed all of the Castanea dentata trees, eliminating it as a canopy dominant. Past logging affected most occurrences. Regenerated forest canopies are even-aged, or have a more even-aged structure. Extreme wind or ice storms occasionally create larger canopy openings, which may provide particularly good sites for Quercus regeneration. Virtually all examples have been strongly affected by introduction of chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica), which killed Castanea dentata trees, eliminating it as a canopy dominant. The introduction, and now widespread establishment, of gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) that favors oaks as food has also affected these forests by causing widespread mortality of overstory trees depending on topographic position and precipitation amounts around defoliation events. Past logging, and now lack of fire, has affected most occurrences by changing canopies to an even-aged, or more even-aged, structure with an understory of shade-tolerant but fire-intolerant species such as Pinus strobus, Acer rubrum, and Acer pensylvanicum. The removal of Castanea dentata from the overstory of these forests is thought to have benefited Carya spp., and their persistence and continued recruitment in contemporary oak-hickory forests may reflect fire exclusion in recent decades. (This) occurs as a large-patch to matrix system. Contiguous areas of tens of thousands of acres once occurred. The oak forests probably make up slightly more than 50% of the landscape in all but the higher elevations of the region. Size of existing occurrences may be strongly affected by separation distances for occurrences. A few remaining occurrences over 10,000 acres are probably present.”

Description Author: M. Schafale, R. Evans, M. Pyne, R. White, S.C. Gawler Version: 29 Apr 2016

USDA-NRCS OSDs for soils included in this PES largely agree, stating that most of these soils are forested with dominant forest trees including chestnut oak, scarlet oak, white oak, Virginia pine, pitch pine, maple, and white pine. In comparison with other PES in the southern Blue Ridge, the vegetation on this site tends to reflect the drier conditions produced by more shallow soils. Pine communities may be important on this site. Some of these may be fire-dependent. Further field investigations are needed to determine differences and identify future projects. PES descriptions are first approximations and are not intended to inform management.

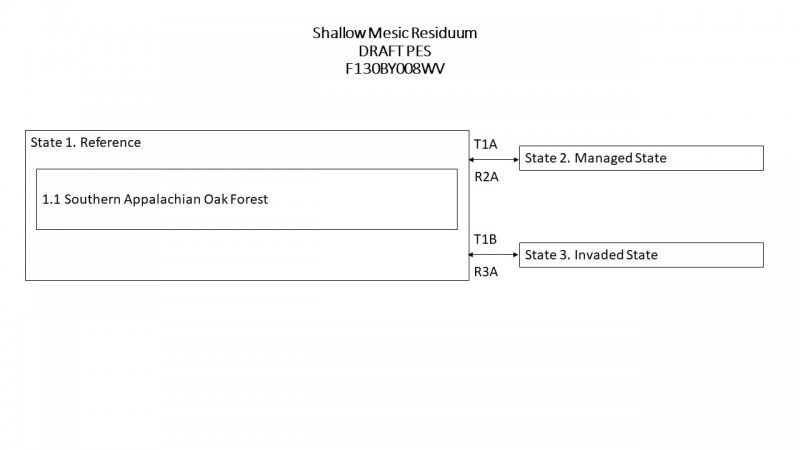

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1

Reference - Southern Appalachian Oak Forest

The reference state includes one major NatureServe ecological systems as described previously, Southern Appalachian Oak Forest. Oaks now dominate this site where American chestnut once would have been a major species dominant in the canopy. Invasive, non-native forest pests and pathogens such as American chestnut blight, dogwood anthracnose, and European gypsy moth (among others) are really the greatest threat to this PES. Most of it is still currently forested, although a good bit of it has been logged, burned or both in the past. Pine communities may be an important component of this PES and future investigations should explore that as well as the role of fire and past disturbance on currently established vegetation communities.

State 2

Managed State

Practically all this site is in forest so, nearly all relevant management consists of forestry practices. Some small acreage is in pasture and hay but that is very small in extent. Further investigation in the field is needed as future projects are identified to refine this PES into what will most likely become multiple ecological sites. Fire may be an important forestry management tool but that should be confirmed through further research.

State 3

Invaded State

Perhaps the greatest challenge to the integrity of this ecological site is the presence of invasive, non-native pests and pathogens. The impact and response varies by species (both of the host and the invader) but often will include combinations of mechanical, biological, chemical and cultural control. Tree breeding programs for genetic resistance and germplasm conservation may be important considerations, especially in front an incoming invasion if reforestation is planned after it passes. It is always best if local genetic material can be used if restoration efforts are attempted.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Conversion to pasture or hayland (site specific)

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Invasion by any number of non-native forest pests and plants

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Abandonment (~100 years until reversion to forest); control of non-native plants and pests where needed

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 1

Management of invasive species (mechanical, chemical, biological control, etc.)

Interpretations

Supporting information

Other references

Comer PJ, Faber-Langendoen D, Evans R, Gawler SC, Josse C, Kittel G, Menard S, Pyne M, Reid M, Schulz K, Snow K, and Teague J. 2003. Ecological Systems of the United States: A Working Classification of U.S. Terrestrial Systems. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia.

Fleming, G. P., P. P. Coulling, K. D. Patterson, and K. Taverna. 2005. The natural communities of Virginia: Classification of ecological community groups. Second approximation. Version 2.1. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage, Richmond, VA. [http://www.dcr.virginia.gov/dnh/ncintro.htm]

Jenkins, M.A. 2007. Vegetation Communities of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Southeastern Naturalist 1:35-56.

National Park Service. Center for Remote Sensing and Mapping Science/University of Georgia. 2009. Great Smoky Mountains National Park Vegetation Mapping Project - Spatial Vegetation Data. http://www1.usgs.gov/vip/grsm/grsmgeodata.zip.

NatureServe. 2009. International Ecological Classification Standard: Terrestrial Ecological Classifications. NatureServe Central Databases. Arlington, VA, U.S.A. Data current as of 06 February 2009.

NatureServe. 2018. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.0. NatureServe, Arlington, VA. U.S.A. Available http://explorer.natureserve.org. Accessed [April 10, 2018].

Soil Survey Staff, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. 2006. Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. Agricultural Handbook 296 digital maps and attributes. Available online. Accessed [5/7/2018].

Soil Survey Staff, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Official Soil Series Descriptions. Available online. Accessed [5/7/2018].

US Geological Survey, Gap Analysis Program (GAP). August 2011. National Land Cover, Version 2.

White, R.D., K.D. Patterson, A. Weakley, E.J. Ulrey, and J. Drake. 2003. Vegetation classification of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Report submitted to BRD-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program. NatureServe, Durham, NC. 376 pp.

Contributors

Belinda Ferro

Tiffany Allen

Acknowledgments

Jennifer Mason, Soil Survey Office Leader, Clinton, TN

Tiffany Allen, Soil Survey Office Leader, Waynesville, NC

Amanda Connor, Soil Scientist, Waynesville, NC

Victor Cruz, Soil Scientist, Waynesville, NC

Nels Barrett, Ecological Site Inventory Specialist (QA), Amherst, MA

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.