Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F134XY003AL

Northern Loess Interfluve - PROVISIONAL

Accessed: 12/22/2024

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 134X–Southern Mississippi Valley Loess

The Southern Mississippi Valley Loess (MLRA 134) extends some 500 miles from the southern tip of Illinois to southern Louisiana. This MLRA occurs in Mississippi (39 percent), Tennessee (23 percent), Louisiana (15 percent), Arkansas (11 percent), Kentucky (9 percent), Missouri (2 percent), and Illinois (1 percent). It makes up about 26,520 square miles. Landscapes consist of highly dissected uplands, level to undulating plains, and broad terraces that are covered with a mantle of loess. Underlying the loess are Tertiary deposits of unconsolidated sand, silt, clay, gravel, and lignite. The soils, mainly Alfisols, formed in the loess mantle. Stream systems of the MLRA typically originate as low-gradient drainageways in the upper reaches that broaden rapidly downstream to wide, level floodplains with highly meandering channels. Alluvial soils, mostly Entisols and Inceptisols, are predominantly silty where loess thickness of the uplands are deepest but grade to loamy textures in watersheds covered by thin loess. Crowley’s Ridge, Macon Ridge, and Lafayette Loess Plains are discontinuous, erosional remnants that run north to south in southeastern Missouri - eastern Arkansas, northeastern Louisiana, and south-central Louisiana, respectively. Elevations range from around 100 feet on terraces in southern Louisiana to over 600 feet on uplands in western Kentucky. The steep, dissected uplands are mainly in hardwood forests while less sloping areas are used for crop, pasture, and forage production (USDA, 2006).

This site occurs throughout the Loess Plains (EPA Level IV Ecoregion: 74b) from western Kentucky south to the Southern Rolling Plains (EPA Level IV Ecoregion: 74c) in southwestern Mississippi.

Classification relationships

All or portions of the geographic range of this site falls within a number of ecological/land classifications including:

-NRCS Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 134 – Southern Mississippi Valley Loess

-Environmental Protection Agency’s Level IV Ecoregion: Loess Plains, 74b (Griffith et al., 1998; Woods et al., 2002; Chapman et al., 2004)

-231H - Coastal Plains-Loess section of the USDA Forest Service Ecological Subregion (McNab et al., 2005)

-LANDFIRE Biophysical Setting 4714270 and NatureServe Ecological System CES203.353 East Gulf Coastal Plain Jackson Plain Prairie and Barrens (LANDFIRE, 2009; NatureServe, 2009)

-LANDFIRE Biophysical Setting 4713060 and NatureServe Ecological System CES203.482 East Gulf Coastal Plain Northern Loess Plain Oak-Hickory Upland, (LANDFIRE, 2009; NatureServe, 2009)

-LANDFIRE Biophysical Setting 4713070 and NatureServe Ecological System CES203.483 East Gulf Coastal Plain Northern Dry Upland Hardwood Forest (LANDFIRE, 2009; NatureServe, 2009)

-Western Mesophytic Forest Region - Mississippi Embayment Section (Braun, 1950)

Ecological site concept

The Northern Loess Interfluve is characterized by deep, well drained soils that formed in a mantle of loess greater than two feet thick. The site principally occurs on broad interfluves of the undulating to rolling Loess Plains. Where dissection of the landscape becomes more pronounced, especially in the hillier eastern portions of the MLRA, the site is positioned on narrow to moderately broad divides. Slopes of this site are generally less than 12 percent. Natural vegetation prior to settlement consisted of a complex mosaic of conditions that ranged from fire-maintained prairies (locally and historically known as “barrens”) to oak-dominated woodlands. Farther south, loblolly and shortleaf pine may increase in abundance, becoming components of the plant community.

Associated sites

| F134XY006AL |

Northern Loess Sideslope - PROVISIONAL |

|---|---|

| F134XY012AL |

Northern Loess Fragipan Upland - PROVISIONAL |

Similar sites

| F134XY210AL |

Western Dry Loess Summit - PROVISIONAL |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Quercus falcata |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Cornus florida |

| Herbaceous |

Not specified |

Physiographic features

The Northern Loess Interfluve is broadly distributed across the largest physiographic subsection or ecoregion of the MLRA, the Loess Plains. West to east, this ecological site extends from the border of the Loess Hills (EPA Level IV Ecoregion: 74a), across the Loess Plains, and into portions of the Southeastern Plains (EPA Level III Ecoregion: 65) where loess continues to cap upland interfluves. North to south, the site extends from the plains in western Kentucky to the border of the Southern Rolling Plains in southwestern Mississippi. The latter forms the southern-most boundary of the site due to warmer average annual air temperatures, greater annual rainfall, and a transition to slightly warmer soils. The Southern Rolling Plains is noted for having more irregular and dissected topography than the Loess Plains to the north and reportedly has a greater concentration of loamy and/or clayey soils and thinner loess deposits (Chapman et al., 2004).

Characteristics of this region generally include undulating uplands, gently rolling hills, and irregular plains. Topographic relief of the Loess Plains is generally low, averaging about 30 to 70 feet. Upland slopes typically range from 0 to 20 percent with 1 to 8 percent being dominant. Elevations in the 300s and 400s are commonplace. In portions of western Kentucky and Tennessee, the undulating pattern of the plains is interrupted by dissected landscapes. Such areas tend to be hillier with steeper slopes and greater relief and appear to be concentrated along the borders of broader valleys and floodplains. As the plains continue eastward, starkness of the terrain becomes even more pronounced, which signals the transition of the Loess Plains to the thin loess-capped ridges, hills, and plateaus along the western edge of the Southeastern Plains.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Interfluve

(2) Plain (3) Divide |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 61 – 198 m |

| Slope | 1 – 12% |

| Water table depth | 152 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

This site falls under the Humid Subtropical Climate Classification (Koppen System). The average annual precipitation for this site from 1980 through 2010 is 56 inches and ranges from 53 in the north to 58 inches in the south. Maximum precipitation occurs in winter and spring and precipitation decreases gradually throughout the summer, except for a moderate increase in midsummer. Rainfall often occurs as high-intensity, convective thunderstorms during warmer periods but moderate-intensity frontal systems can produce large amounts of rainfall during winter, especially in the southern part of the area. Snowfall generally occurs in the north during most years. However, accumulations are generally less than 12 inches and typically melt within 3 to 5 days. South of Memphis, winter precipitation sometimes occurs as freezing rain and sleet. The average annual temperature is 60 degrees F and ranges from 58 in the north to 64 degrees F in the south. The freeze-free period averages 222 days and ranges from 206 days in the north to 252 days in the south. The frost free period averages 197 days and ranges from 191 in the north to 224 days in the south.

The broad geographic distribution of this site north to south naturally includes much climatic variability with areas farther south having a longer growing season and increased precipitation. These climatic factors likely lead to important differences in overall plant productivity and key vegetation components between the southern and northern portions of this site. As future work proceeds, the current distribution of the Northern Loess Interfluve will likely be revised with a “central” site interjected between the northern and southern extremes of this MLRA.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 197 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 222 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 1,422 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 4. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 5. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BARDWELL 2 E [USC00150402], Bardwell, KY

-

(2) GILBERTSVILLE KY DAM [USC00153223], Gilbertsville, KY

-

(3) BATESVILLE 2 SW [USC00220488], Batesville, MS

-

(4) CANTON 4N [USC00221389], Canton, MS

-

(5) GRENADA [USC00223645], Grenada, MS

-

(6) SENATOBIA [USC00227921], Coldwater, MS

-

(7) VICKSBURG MILITARY PK [USC00229216], Vicksburg, MS

-

(8) BOLIVAR WTR WKS [USC00400876], Bolivar, TN

-

(9) UNION CITY [USC00409219], Union City, TN

-

(10) PADUCAH [USW00003816], West Paducah, KY

-

(11) JACKSON INTL AP [USW00003940], Pearl, MS

-

(12) LOVELACEVILLE [USC00154967], Paducah, KY

-

(13) OAKLEY EXP STN [USC00226476], Raymond, MS

-

(14) COLLIERVILLE [USC00401950], Collierville, TN

-

(15) COVINGTON 3 SW [USC00402108], Covington, TN

-

(16) DRESDEN [USC00402600], Dresden, TN

-

(17) BROOKPORT DAM 52 [USC00110993], Paducah, IL

-

(18) YAZOO CITY 5 NNE [USC00229860], Yazoo City, MS

-

(19) NEWBERN [USC00406471], Newbern, TN

-

(20) MURRAY [USC00155694], Murray, KY

-

(21) HOLLY SPRINGS 4 N [USC00224173], Holly Springs, MS

-

(22) LEXINGTON [USC00225062], Lexington, MS

-

(23) MILAN EXP STN [USC00406012], Milan, TN

Influencing water features

This site is not influence by a hydrologic regime. Of note, inclusions of highly localized depressions that support seasonal ponding have been observed on level, broad interfluves of this site. The presence of such features do not influence the overall characteristics of this particular ecological site.

Soil features

The parent material of this site is a mantle of highly-erodible loess of eolian origin. Loess thickness of the site ranges from 2 to 40 feet with an average depth of 10 to 20 feet over the central portion of the plains. The greatest depths occur along the border of the Loess Plains and the Loess Hills where about 30 to 40 feet of loess blanket the uplands. Loess depths progressively thins eastward to about 2 feet thick in portions of the Southeastern Plains.

The soils of this site are well drained, have moderate permeability in the upper part, and consist of silt loam surface horizons with subsoils that include silt loam, silty clay loam, loam, to gravelly sandy loam. These soils are not affected by seasonal wetness. The principal soils of this ecological site are the Memphis (Fine-silty, mixed, active, thermic Typic Hapludalfs), Feliciana (Fine-silty, mixed, active, thermic Ultic Hapludalfs), with secondary soils of Lexington (Fine-silty, mixed, active, thermic Ultic Hapludalfs) and Brandon (Fine-silty, mixed, semiactive, thermic Typic Hapludults) series. Base saturations (a measure of a soil’s natural fertility) vary widely among these soils. Memphis soils have base saturations that generally exceed 60 percent, a taxonomic criteria for the series. Feliciana soils are similar to Memphis soils but have a base saturation of less than 60 percent but are generally higher than 40 percent. Base saturations for Lexington soils range from 36 to 59 percent but are commonly less than 40 percent. Brandon soils have base saturations less than 35 percent. Given the soils’ inherent low fertility and dense, gravelly subsoils, Brandon soils are “provisionally” included in this site until a thorough inventory has been conducted and results analyzed. It is highly likely that Brandon soils support and produce a much drier and less productive plant community than either Memphis, Feliciana, and/or Lexington soils.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Silt loam (2) Silty clay loam |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate to rapid |

| Soil depth | 203 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

12.7 – 22.1 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

0% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

5 – 6 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 50% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

1 – 4% |

Ecological dynamics

This provisional ecological site is broadly mapped across MLRA 134. The site occurs across one of the most distinctive landforms of the region, the broad, gently sloping and undulating interfluves and divides of the Loess Plains. Where dissection of the landscape increases, the site becomes compressed along narrower ridgetops and summits. This upland site receives full insolation and accordingly, can become quite droughty.

Where this site occurs along the transition of the Loess Hills to the Loess Plains, loess thickness can be very deep, often greater than 20 feet, locally (D. Thomas, personal communication). Proceeding eastward, loess depths progressively thin with some areas along the eastern boundary of the MLRA having less than 24 inches of the mantle remaining. This gradient in loess depth can exert strong influences on vegetation, and accordingly, species composition may vary locally across this gradient (Bryant et al., 1993). Areas supporting very deep loess soils have been observed to produce exceptional growth by a wide range of hardwoods and competition among species can become intense (Johnson, 1958; Hodges, 1995; Goelz and Meadows, 1995). Conversely, soils that have a thin loess cap (especially less than 3 feet thick) tend produce a drier association and diversity appears to decrease overall (personal observations).

Determining and ascribing reference conditions for this site is extremely challenging. The pre-settlement plant community of this site was removed and/or severely altered soon after settlement nearly 200 years ago, and there are no intact examples of that system remaining. The only source of information that provides some indication of the former natural communities of this site are accounts from early settlers, observations recorded in state geologic surveys, and clues pieced together from remnant strands occurring in small woodlots, along roadsides, and in old fields. With no example of the pre-settlement plant community remaining, reference conditions of this site have been arbitrarily chosen to reflect the range of physiognomic characteristics and/or vegetation types that reportedly occurred.

The perceived reference community phases of this ecological site consisted of: woodland (includes areas of closed forest) and prairie or savanna. Of the two, the prevailing community phase may have been woodland and/or forest (NatureServe, 2009). This conclusion is drawn from accounts and broad characterizations provided in Loughridge (1888), Killebrew (1879), and Lowe (1921) with reference to the site’s distribution through western Kentucky, West Tennessee, and Mississippi, respectively. Based on those combined accounts, the predominant vegetation community of the “brown loam soil” (i.e., loess of varying thickness) was essentially an oak – hickory or mixed hardwood association with an increased presence or entrance of loblolly pine and shortleaf pine to the south in Mississippi (the latter reported by Lowe, 1921).

The second community phase, prairie and/or savanna, represents a system that occurred in the northern portion of this site in western Kentucky and portions of northwest Tennessee. Perhaps the best evidence regarding the presence and distribution of this vegetation type was a map provided by Loughridge (1886) and his descriptions in a later volume (Loughridge, 1888). Loughridge illustrated the general distribution of broadly defined land cover types across the Jackson Purchase of western Kentucky. Two significant cover types on his map coincide with the distribution of this ecological site: the “Brown Loam ‘Timbered Lands’ and “Brown Loam ‘Barrens’ (originally Prairie)” (single quotes and parentheses represent his punctuations). His map depicted “barrens” (prairies) extending southward into northwest Tennessee. Perhaps the best evidence and description of that former community in Tennessee was an account from an early settler into the region, Colonel John A. Gardner. Gardner’s (1876) eloquent description of the “appearance of the country” clearly evoke imagery of a nearly treeless, herbaceous-dominated plain.

The distribution of the prairie community phase farther south through Tennessee and Mississippi on loessal soils are not as well documented. But, wherever local indigenous communities existed and fire was an important management tool, patches of open, herbaceous vegetation likely persisted. Conceivably, such openings would have graded to the surrounding woodland matrix by transitioning from treeless prairie to savanna and on to woodland conditions.

Today, a vastly different picture portrays this ecological site. The predominant land use of this site is agriculture production, particularly in areas of little relief and where loess deposits are thickest – the core of the Loess Plains. This region is known for its fertile soils and consistently high yields, and some areas likely have been under production for at least 175 years.

Secondary uses of this site include some pasturage and timber management. These uses rarely occur on prime cropland and are typically relegated to hillier or more dissected landscapes. Incidentally, these uses increase in prominence and importance along the eastern edge of the MLRA where loess depths are thin and conditions more droughty.

An additional use is recognized and represented for this site: conservation. This use or “state” is provided to represent the range of conservation related actions and management that either “reconstructs” the perceived historic conditions (both composition and ecological processes) or enhances a degraded and highly altered location by planting species native to this site.

Of particular note and concern, the broad range of soils “provisionally” associated with this site vary in a number of critical soil properties including loess thickness, natural fertility (or base saturation percentages), and subsoil texture, to name a few. Further confounding these influences, climate differences also occur north to south. The breadth of environmental variability of this site, as it is currently mapped, necessitates future investigations to ascertain the collective influences of both climate and soils on local vegetation communities. Future work may culminate in the determination of a latitudinal division or break of this site (if it is justified) and a much more accurate and defensible soil – vegetation community correlation. Succinctly put, one or more ecological sites are likely to be defined based on soil differences and climatic influences. This provisional site is essentially a foundation from which to begin future soil – site surveys and ecological site inventories.

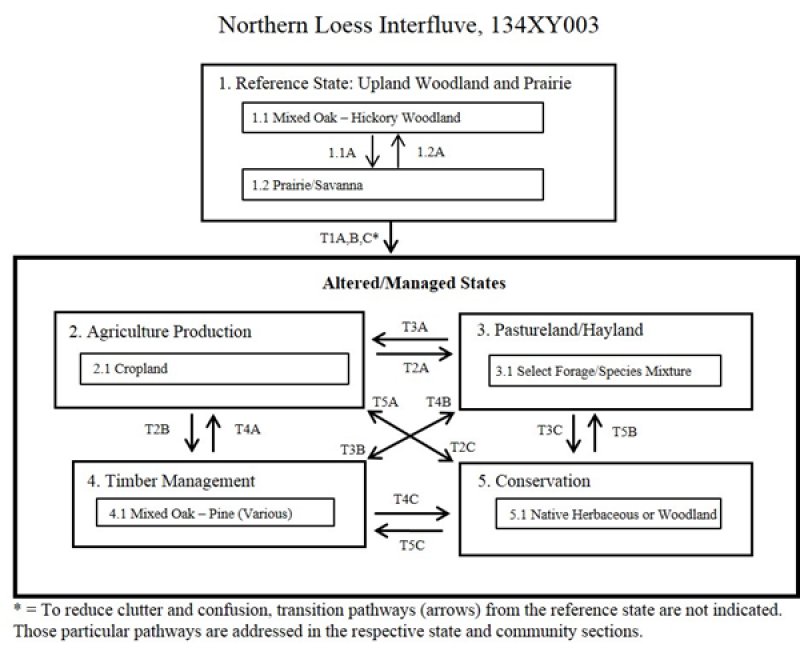

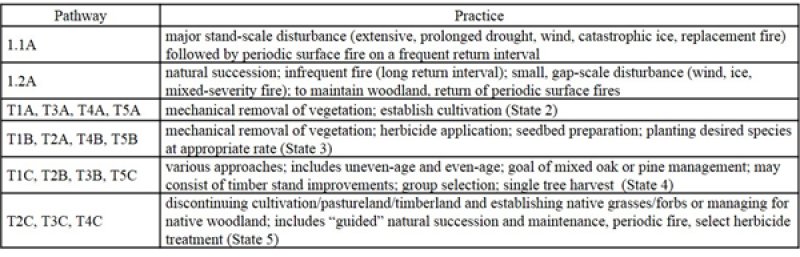

Following this narrative, a “provisional” state and transition model is provided that includes the “perceived” reference state and several alternative (or altered) vegetation states that have been observed and/or projected for the Northern Loess Interfluve ecological site. This model is based on limited inventories, literature, expert knowledge, and interpretations. Plant communities will differ across MLRA 134 due to natural variability in climate, soils, and physiography. Depending on objectives, the reference plant community may not necessarily be the management goal.

The environmental and biological characteristics of this site are complex and dynamic. As such, the following diagram suggests pathways that the vegetation on this site might take, given that the modal concepts of climate and soils are met within an area of interest. Specific locations with unique soils and disturbance histories may have alternate pathways that are not represented in the model. This information is intended to show the possibilities within a given set of circumstances and represents the initial steps toward developing a defensible description and model. The model and associated information are subject to change as knowledge increases and new information is garnered. This is an iterative process. Most importantly, local and/or state professional guidance should always be sought before pursuing a treatment scenario.

State and transition model

Figure 6. STM - Northern Loess Interfluve

Figure 7. Legend - Northern Loess Interfluve

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

States 2 and 5 (additional transitions)

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Upland Woodland and Prairie

The reference state of this ecological site was chosen to represent the breadth of community types that historically occurred across the loess capped uplands of MLRA 134. Exemplary examples of the full range of plant communities and ecological processes that were once commonplace on this ecological site no longer exist. Where trees occur today, they typically form a closed canopy forest comprised of exotic species and an understory entangled by native and non-native vines. Vestiges of this once vast system are primarily relegated to cutover forest blocks, narrow roadway and powerline corridors, and corners of old fields and pastures that now hold the only remaining examples of native prairie vegetation (Estes et al., 2016) – typically in small clumps. Therefore, a complete and exhaustive description and treatment of this system cannot be provided. However, some native plant species that comprised the woodlands and prairies of long ago still exist. It is from these instances coupled with historical accounts that we draw upon the reference conditions of the site. The name of the reference state, woodland and prairie, implies the existence of systems maintained and directly influenced by fire. The accounts provided by Loughridge (1888), Gardner (1876), and many others are testament of the historic importance of fire on the Loess Plains, some natural but most were first induced by Native Americans and second, by early settlers striving to maintain and enhance pasturage.

Community 1.1

Mixed Oak – Hickory Woodland

This community phase represents what is perceived to be the predominant condition or vegetation type associated with the loess capped uplands. The structural descriptor of “woodland” in the community name represents what likely occurred in areas where fire from adjoining systems (e.g., prairies and savannas) moved into and across areas that supported trees. Most current community classifications associated with the distribution of this site recognize “forest” as the single structural descriptor (e.g., NatureServe, 2009). This is mainly due to the predominant structural characteristic of today’s “stand” of trees. This does not negate the existence of closed canopy forests on this site. Closed forests likely developed in areas where loess thickness was very deep and in areas where a natural fire break existed, such as within highly dissected landscapes (Estes et al., 2016). Areas supporting very deep loess deposits are reknown for producing tremendous hardwoods (see Johnson, 1958). Without periodic fire or some form of frequent disturbance, forest growth on these soils are incredible with trees of some species capable of attaining 120 feet in 50 years of growth (see Broadfoot, 1976). In addition to a range of structural characteristics, community composition varied across the distribution of this site, both west to east and north to south. Along the western portion of the Loess Plains, the moist, deep loess soils certainly influenced tree growth and composition. Where moisture was greatest, species likely resembled those of the summits of the Loess Hills, which consisted of cherrybark, white, black, northern red, Shumard’s, water, chinkapin, southern red, and post oak. Associates, in varying portions, may have included sweetgum, tuliptree, white ash, hickory, elm, black walnut, black gum, persimmon, and sassafras. Important midstory and understory components likely consisted of hophornbeam, flowering dogwood, and redbud. Moving eastward onto the central portion of the Loess Plains, the importance and presence of some species may have started to fade such as Shumard’s, northern red, tuliptree, and walnut with a concomitant increase of drier associates such as southern red, post, and blackjack oak and hickory. Here, the movement of fire may have had few natural breaks and the understory more open with an increase in herbaceous ground cover. Where dissection of the landscape increased, fire may have had more difficulty in moving across large expanses, resulting in an increase in forest structure. Transition to a distinctly dry plant association occurred along the eastern border of this site where the loess cap thinned to within 3 feet. Canopy associates of the higher and drier locations would have consisted of post, southern red, blackjack, and black oak along with hickory, black gum, hophornbeam, dogwood, sourwood, persimmon, sassafras, and winged elm. It is possible that shortleaf pine may have occurred locally in the northern portions of the site (e.g., on Brandon soils) but its presence, along with loblolly pine, was more concentrated to the south in Mississippi.

Community 1.2

Prairie/Savanna

In relation to the full distribution of this ecological site, this community phase is representative of a relatively small area, which is primarily restricted to the site’s northern extent in western Kentucky and northwest Tennessee. However, it is possible that the system existed in small, local patches farther south. This site may have been more representative of thin loess and non-loess soils rather than on the deeper loess soils of the plains (NatureServe, 2009). However, the account by Gardner (1876), which is from an area that supports deep loess soils (i.e., greater than 4 feet thick) in northwest Tennessee, challenges this supposition to some degree. The presence of humans coupled with the ease with which fire moved across the landscape (e.g., areas of little relief) likely played a more significant role than loess depth alone. Fire was a critical and frequent factor for maintaining this community phase, and most fires were deliberately set (Gardner, 1876; Loughridge, 1888). Gardner (1876) provided general characterizations of the plains and mentioned “barren grass” growing three to four feet high, and being able to see a horseman miles away. Referring to the nearly treeless plains, he specifically mentioned woody vegetation occurring as “…small clumps of scrubby blackjack oak, post oak, and hickory bushes a few feet high, interspersed with patches of sumac and hazel.” Examples of this open, herbaceous system likely consisted of a dense herbaceous layer that was dominated by tall grasses such as big bluestem, little bluestem, and Indian grass (DeSelm, 1989; NatureServe, 2009). Select associates of the tall grasses likely included switchgrass, splitbeard bluestem, threeawns, panic-grass, wild indigo, blazing star, evening-primrose, New England aster, compass plant, goldenrod, lanceleaf tickseed, tall tickseed, rattlesnake master, ashy sunflower, flowering spurge, Virginia strawberry, purple milkwort, slender milkwort, Sampson’s snakeroot, agave, New Jersey tea, goat’s-rue, various milkweeds, sedges, and many additional species (Heineke, 1987; also selected from an exhaustive list provided D. Estes). This broad, open system transitioned to a dense, oak – hickory forest within 30 years of settlement and cessation of frequent fires (DeFriese, 1880; Loughridge, 1888).

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

This pathway represents a major stand-scale disturbance that effectively removed the overstory such as extensive, prolonged drought, wind, catastrophic ice, tree girdling/removal by humans, and/or stand replacement fire. Such catastrophic events would then be followed by low-intensity surface fires on a frequent return interval, which would support transition to prairie and/or savanna conditions.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

This pathway represents a return to an open woodland or forest structural characteristic. Processes leading to woodland conditions is a cessation of fire or fire occurring on a much longer return interval. Disturbance occurs or returns at the gap-scale, often single tree (i.e., less than 1 acre).

State 2

Agriculture Production

Agriculture production is the dominant land use activity on this site, today. Most cropland is relegated to the Loess Plains and in areas of little topographic relief (generally long, gradual slopes).

Community 2.1

Cropland

Crops may include soybean, corn, wheat, canola, and cotton with tobacco grown locally in the north.

State 3

Pastureland/Hayland

This state is representative of sites that have been converted to and maintained in pasture and forage cropland, typically a grass – legume mixture. For pastureland, planning or prescribing the intensity, frequency, timing, and duration of grazing can help maintain desirable forage mixtures at sufficient density and vigor (USDA-NRCS, 2010; Green et al., 2006). Overgrazed pastures can lead to soil compaction and numerous bare spots, which may then become focal points of accelerated erosion and colonization sites of undesirable plants or weeds. Establishing an effective pasture management program can help minimize the rate of weed establishment and assist in maintaining vigorous growth of desired forage. An effective pasture management program includes: selecting well-adapted grass and/or legume species that will grow and establish rapidly; maintaining proper soil pH and fertility levels; using controlled grazing practices; mowing at proper timing and stage of maturity; allowing new seedings to become well established before use; and renovating pastures when needed (Rhodes et al., 2005; Green et al., 2006). It is strongly advised that consultation with State Grazing Land Specialists and District Conservationists at local NRCS Service Centers be sought when assistance is needed in developing management recommendations or prescribed grazing practices.

Community 3.1

Select Forage/Species Mixture

This community phase represents commonly planted forage species on pasturelands and haylands. The suite of plants established on any given site may vary considerably depending upon purpose, management goals, usage, and soils. Most systems include a mixture of grasses and legumes that provide forage throughout the growing season. Cool season forage may include tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus), orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata), white clover (Trifolium repens), and red clover (T. pratense), and warm season forage often consists of bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum), and annual lespedeza (Kummerowia spp.). Several additional plants and/or species combinations may be desired depending on the objectives and management approaches and especially, local soils. Should active management (and grazing) of the pastureland be halted, this phase will transition to “old field” conditions, which is the transitional period between a predominantly open, herbaceous field and the brushy stage of a newly initiated stand of trees.

State 4

Timber Management

This state represents a broad range of management objectives, options, and stand conditions including woodlots allowed to grow or revert naturally; repeated single-tree harvests (often high-graded); carefully prescribed treatments; and conversion to a monoculture or single-species stand. Various management or silvicultural methods can lead to very different structural and compositional results. For prescribed management options, methods are diverse, which include even-aged (e.g., clearcut and shelterwood) and uneven-aged (single tree, diameter-limit, basal area, group selection, etc.) approaches. Included within these approaches is an option to use disturbance mechanisms (e.g., fire, TSI, etc.) to reduce competition and achieve maximum growth potential of the desired species. Inherently, these various approaches result in different community or “management phases” and possibly alternate states, depending on one’s perspective. The decision to represent these varying approaches and management results into a single state and phase at this time hinges on the need for additional information in order to formulate definitive pathways, management actions, and community responses. Forthcoming inventories of this site will provide more detail on this state and associated management phases.

Community 4.1

Mixed Oak – Pine (Various)

Some of the most desirable timber on this site consists of oak. Depending on the desired end product, management activities will differ. Management for oak dominant stands may be achieved by shelterwood and/or seed tree approaches. Managing for other hardwoods, and pine to the south, may only require timber stand improvement methods or artificial regeneration may be called for where other hardwoods predominate. Fire can be a management tool on this site given its location on drier summit and shoulder slope positions. Low intensity ground fires on a frequent return interval can be effective for reducing competition and potentially enhancing production of individual trees. Finding the appropriate approach for a given stand and environment necessitates close consultation with trained, experienced, and knowledgeable forestry professionals. It is strongly urged and advised that professional guidance be secured and a well-designed silvicultural plan developed in advance of any work conducted.

State 5

Conservation

This alternative state is included to represent the range or breadth of conservation actions that may be implemented and established should other land uses be discontinued within a given location. Several actions may be chosen including the standard of establishing native warm season grasses; establishing a suite of suitable forbs for pollinators; establishing select native trees and managing for open woodland/savanna conditions. Of the options available, the one that best mimics the perceived reference conditions of this site would provide the best case conservation scenario. This action requires a concerted effort to reestablish herbaceous species most common to the prairies (“barrens”) of western Kentucky, West Tennessee and Mississippi with the possible addition of widely spaced hardwoods (e.g., upland oaks from the reference state) mimicking savanna to open woodland conditions. If at all possible, the herbaceous species established should be derived from the “wild types” (genetic stock) from the Loess Plains or from adjoining ecoregions. This action would help preserve the unique genetic material from the area and would help to reintroduce the native prairie system back into a portion of its former range.

Community 5.1

Native Herbaceous or Woodland

This community phase represents the establishment of select native plants to meet conservation objectives on this site. As alluded to above, the best case scenario is the establishment of native species selected from the genetic stock of the Loess Plains or neighboring ecoregions. Herbaceous species suitable for establishing on this site include big bluestem, Indian grass, little bluestem, threeawn, wild oat grasses, panic grass, wild indigo, blazing stars, evening-primrose, asters, black-eyed susans, compass plant, coneflowers, goldenrod, lanceleaf tickseed, tall tickseed, rattlesnake master, sunflowers, flowering spurge, Virginia strawberry, purple milkwort, slender milkwort, Sampson’s snakeroot, mountain mints, agave, New Jersey tea, goat’s-rue, various milkweeds, sedges, among many others (partially derived from Heineke, 1987 and D. Estes). Key to the perpetuation and maintenance of this system is frequent fire, generally on a 1 to 3 year return interval (judgement based on early accounts of frequent burning; e.g., Loughridge, 1888). Although, LANDFIRE (2009) models suggest replacement or surface fire every 10 years maintains the early development characteristics of this system. Managing for native open woodlands on this site entails establishment and maintenance of the most commonly reported tree species, which generally includes southern red oak, blackjack oak, post oak, white oak, black oak, pignut hickory, mockernut hickory, and shrub/small tree stratum of hophornbeam, dogwood, deerberry, and hazelnut among others. Canopy closure will range from 20 to 60 percent and coverage of the herbaceous layer may exceed that of the trees. Shrubs are widely scattered and limited in abundance and coverage. Trees are widely spaced or dispersed and open-grown. Mixed-severity fire every 20 years or low intensity surface fire within every 10 years is modeled to maintain the open woodland condition (LANDFIRE, 2009).

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Actions include mechanical removal of vegetation and stumps; preparation for and establishment of cultivation (State 2).

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

This pathway represents an attempt to convert the woodland community to pasture or forage production. Actions include clearing, stump removal, seedbed preparation, and the establishment of desired plants (State 3).

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

This pathway initially consisted of fire suppression (for areas formerly in prairie or woodland conditions) followed by a series of selective cuttings for firewood, construction, staves, and income. Many stands have been high-graded due to repeated, unscrupulous harvest methods.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Seedbed preparation and establishment of desired forage/grassland mixture.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

This pathway represents prescribed management strategies for transitioning former cropland to one that meets timber stand composition and production objectives. For enhanced oak production, actions may include artificial regeneration and reduction of oak competition. Managing for mixed hardwood production may require exotic species control and general timber stand improvement practices. The final option of this pathway is the establishment of a pine monoculture or plantation. Establishment of the latter may be most successful on thin loess soils and/or in the southern portions of the site.

Transition T2C

State 2 to 5

This pathway represents the decision to discontinue cultivation/production and establish native grasses/forbs or trees on this site. This action also includes management activities to “guide” natural succession. Actions may include prescribed fire for maintaining and enhancing herbaceous establishment and herbicide treatments for controlling exotic species invasions and to ensure select tree establishment.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

Actions include removal of vegetation; herbicide treatment of residual plants; and preparation for cultivation.

Transition T3B

State 3 to 4

This pathway represents natural succession of former pasture to non-managed “woods” or forest or implementing prescribed management strategies for meeting timber stand composition and production objectives. For enhanced oak production, actions may include artificial regeneration and reduction of oak competition. Managing for mixed hardwood production may require exotic species control and general timber stand improvement practices. The final option of this pathway is the establishment of a pine monoculture or plantation. Establishment of the latter may be most successful on thin loess soils and/or in the southern portions of the site.

Transition T3C

State 3 to 5

This pathway represents the decision to discontinue grazing/non-native forage management and establish native grasses/forbs or trees on this site. This action also includes management activities to “guide” natural succession. Actions may include prescribed fire for maintaining and enhancing herbaceous establishment and herbicide treatments for controlling exotic species invasions and to ensure select tree establishment.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 2

Actions include removal of vegetation; herbicide treatment of residual plants; and preparation for cultivation.

Transition T4B

State 4 to 3

Seedbed preparation and establishment of desired forage/grassland mixture.

Transition T4C

State 4 to 5

This pathway represents the decision to discontinue timber management or forest cover and establish native grasses/forbs or woodland/savanna on this site. This decision also includes the implementation of management activities to “guide” natural succession and conservation end goals. Actions may include prescribed fire for maintaining and enhancing herbaceous establishment and herbicide treatments for controlling exotic species invasions.

Transition T5A

State 5 to 2

This pathway represents the discontinuation of conservation practices and a return to production.

Transition T5B

State 5 to 3

This pathway represents the discontinuation of conservation practices and a return to pasture and/or hayland management entailing removal of vegetation, seedbed preparation, and establishment of desired forage/grassland mixture.

Transition T5C

State 5 to 4

This pathway represents the discontinuation of conservation practices and establishing prescribed management strategies for timber stand composition and production objectives. For enhanced oak production, actions may include artificial regeneration and reduction of oak competition. Managing for mixed hardwood production may require exotic species control and general timber stand improvement practices. The final option of this pathway is the establishment of a pine monoculture or plantation. Establishment of the latter may be most successful on thin loess soils and/or in the southern portions of the site.

Additional community tables

Interpretations

Supporting information

Other references

Braun, E.L. 1950. Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America. Hafner Press, New York. 596 p.

Broadfoot, W.M. 1976. Hardwood suitability for and properties of important Midsouth soils. Res. Pap. SO-127. U.S. Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station, New Orleans, LA: 84 p.

Bryant, W. S., W. C. McComb, and J. S. Fralish. 1993. Oak-hickory forests (western mesophytic/oak-hickory forests). In: W. H. Martin, S. G. Boyce, and A. C. Echternacht. (eds.) Biodiversity of the southeastern United States. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York. p. 143-201.

Chapman, S.S, G.E. Griffith, J.M. Omernik, J.A. Comstock, M.C. Beiser, and D. Johnson. 2004. Ecoregions of Mississippi (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey (map scale 1:1,000,000).

DeFriese, L.H. 1880. Report on the timbers of the district west of the Tennessee River, commonly known as the Purchase District. In: Geological Survey of Kentucky. Vol. 5. p.125-158.

DeSelm, H.R. 1989. The barrens of West Tennessee. p. 3-27. In: Scott, A.F. (ed.). Proceedings of the contributed papers session of the second annual symposium on the natural history of lower Tennessee and Cumberland River valleys. Center for Field Biology of Land Between the Lakes, Austin Peay State University, Clarksville, Tennessee.

Estes, D. personal communication. Botanist, Ecologist, and Professor. Austin Peay State University. Clarksville, TN.

Estes, D., M. Brock, M. Homoya, and A. Dattilo. 2016. A Guide to Grasslands of the Mid-South. Published by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Tennessee Valley Authority, Austin Peay State University, and the Botanical Research Institute of Texas.

Gardner, J.A. 1876. Historical address delivered at Dresden, Tennessee, July 4, 1876. Reproduced by Georgia L. Arnold (descendant). Address housed and curated at Paul Meek Library, University of Tennessee, Martin. Martin, Tennessee.

Goelz, J.C.G. and J.S. Meadows. 1995. Hardwood regeneration on the loessial hills after harvesting for uneven-aged management. In: Edwards, M.B. (ed.) Proceedings of the Eighth Biennial Southern Silvicultural Research Conference. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-1. U.S. Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, NC: 392-400.

Green, Jonathan D., W.W. Witt, and J.R. Martin. 2006. Weed management in grass pastures, hayfields, and other farmstead sites. University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service, Publication AGR-172.

Griffith, G.E., J.M. Omernik, S. Azevedo. 1998. Ecoregions of Tennessee (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, VA., U.S. Geological Survey (map scale 1:1,000,000).

Heineke, T.E. 1987. The Flora and Plant Communities of the Middle Mississippi River Valley. Doctoral Dissertation, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL. 669 p.

Hodges, J.D. 1995. The southern bottomland hardwood region and brown loam bluff subregion. In: Barrett, J.W. (ed.) Regional Silviculture of the United States. Third Edition. John Wiley and Sons, New York: 227-269.

Johnson, R.L. 1958. Bluff Hills – Ideal for hardwood timber production. Southern Lumberman 197(2456): 126-128.

Killebrew, J.B. 1879. West Tennessee: Its Resources and Advantages. Cheap Homes for Immigrants. Tavel, Eastman, and Howell, Nashville, TN.

LANDFIRE. 2009. LANDFIRE Biophysical Setting Models. Biophysical Setting 46-47. (2009, February and March – last update). Homepage of the LANDFIRE Project, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; U.S. Department of Interior, [Online]. Available: http://www.landfire.gov/index.php (Accessed: 1 July 2014).

Loughridge, R.N. 1886. Agricultural Map of the Jackson Purchase. Geological Survey of Kentucky. Scale 1:300,000.

Loughridge, R.N. 1888. Report on the Geological and Economic Features of the Jackson Purchase Region, Embracing the Counties of Ballard, Calloway, Fulton, Graves, Hickman, McCracken, and Marshall. Geologic Survey of Kentucky. Frankfort, KY.

Lowe, E.N. 1921. Plants of Mississippi. A list of flowering plants and ferns. Mississippi State Geological Survey. Bulletin No. 17. 259 p.

McNab, W.H.; Cleland, D.T.; Freeouf, J.A.; Keys, Jr., J.E.; Nowacki, G.J.; Carpenter, C.A., comps. 2005. Description of ecological subregions: sections of the conterminous United States [CD-ROM]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 80 p.

NatureServe. 2009. International Ecological Classification Standard: Terrestrial Ecological Classifications. NatureServe Central Databases. Arlington, VA, U.S.A. Data current as of 06 February 2009.

Rhodes, G.N., Jr., G.K. Breeden, G. Bates, and S. McElroy. 2005. Hay crop and pasture weed management. University of Tennessee, UT Extension, Publication PB 1521-10M-6/05 (Rev). Available: https://extension.tennessee.edu/washington/Documents/hay_crop.pdf.

Thomas, D. personal communication. Soil Scientist. NRCS, Soil Survey Division (retired). Milan, TN.

[USDA-NRCS] United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2006. Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbook 296.

[USDA-NRCS] United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2010. Conservation Practice Standard: Prescribed Grazing. Practice Code 528. Updated: September 2010. Field Office Technical Guide, Notice 619, Section IV. [Online] Available: efotg.sc.egov.usda.gov/references/public/ne/ne528.pdf.

[USDA-NRCS] United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2016. Official Soil Series Descriptions. Available online: https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/osdname.asp. (Accessed: 17 May 2016).

Woods, A.J., J.M. Omernik, W.H. Martin, G.J. Pond, W.M. Andrews, S.M. Call, J.A. Comstock, and D.D. Taylor. 2002. Ecoregions of Kentucky (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, VA., U.S. Geological Survey (map scale 1:1,000,000).

Contributors

Barry Hart

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | |

| Approved by | |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.