Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F148XY029PA

Moist, High Base-Saturation, Riparian Zone, Ecotonal Meadow-Shrub-Forest

Last updated: 3/10/2021

Accessed: 03/01/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

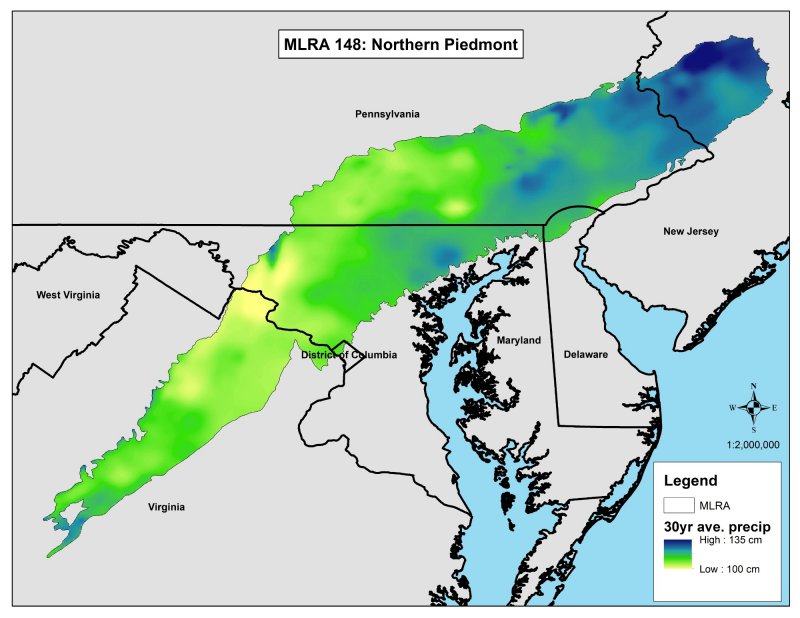

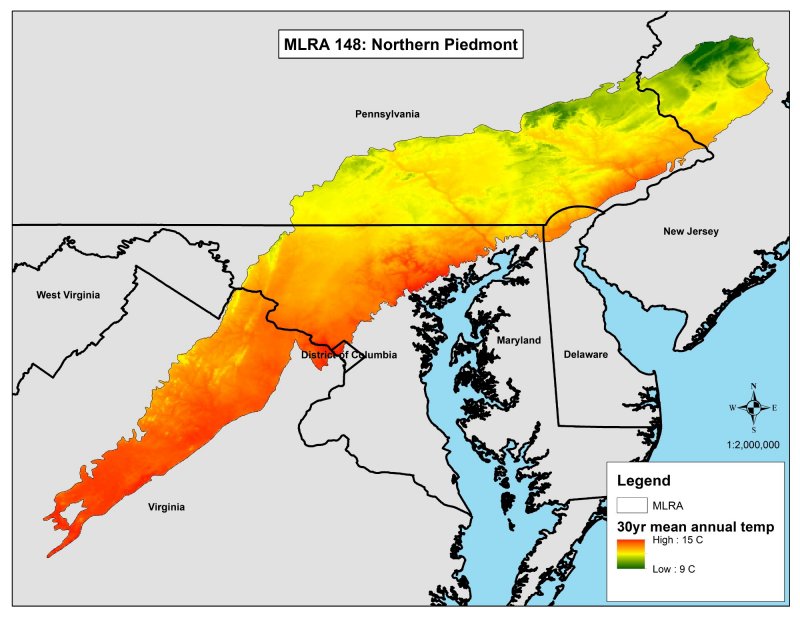

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 148X–Northern Piedmont

This ecological site description was developed for the Northern Piedmont Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 148 as defined by USDA Handbook 296. The Northern Piedmont is a major land resource area within the North Atlantic Slope Diversified Farming Land Resource Region (LRR). The Northern Piedmont MLRA extends from northeast to southwest for approximately 325 miles (525 km) and is approximately 100 miles (160 km) inland from the Atlantic coast. It is approximately 12,800 square miles (33,150 square kilometers) and is spread across portions of Virginia (30%), Maryland (21%), Pennsylvania (38%), Delaware (1%), and New Jersey (10%) (USDA-NRCS, 2006).

Most of the land in the Northern Piedmont is privately owned. Farming is highly diversified, and common crops include truck crops, horticultural trees, fruits, soybeans, grain, forage, poultry, beef, and dairy cattle. The Washington D.C. to Boston “megalopolis” development corridor dominates an important extent of the land (1/3 or more), and urban areas are encroaching on farmland and woodlands across the region. The remaining forests commonly are on steep slopes, rocky soils, or riparian zones where both agriculture and development are difficult (USDA-NRCS, 2006; Woods et al., 1999).

The extent to which indigenous peoples altered the precolonial vegetation of the region is unclear. Some evidence indicates that savannah-like woodlands and grasslands occupied portions of the Northern Piedmont at the onset of European settlement. The evidence suggests that the indigenous communities may have used fire as a land-management tool.

The vegetation communities across the Northeast began experiencing significant influences from European settlers in approximately 1650. These influences included widespread agricultural land clearing, forest harvesting, charcoal production, and the introduction of exotic species, insects, and disease vectors, especially chestnut blight. The loss of American chestnut has been significant across the entire eastern United States. This loss, however, may be less ecologically significant in portions of the Northern Piedmont. For example, little evidence exists to suggest that American chestnut was an important constituent of forests growing on soils derived from carbonate parent materials (Virginia DCR, 2016).

The acreage of forest across the Northern Piedmont reached its low in the mid-nineteenth century. The acreage then increased as agriculture expanded to the Midwest and industrialization concentrated populations into urban areas. The Northern Piedmont includes some of the most productive farmland in the East, so farm abandonment was not as common in MLRA 148 as in other parts of the Northeast. Regionally, widespread farm abandonment led to a trend of reforestation. The recovering forest appears to have included all native forest species, with the notable exception of American chestnut. The proportions, however, were different (maples are notably more common) and more homogenous. The current forest vegetation communities in the Northern Piedmont likely do not show the same level of sorting by local climatic and edaphic factors as influenced precolonial forest composition. Urban sprawl is once again removing land from vegetation cover, but, in the Northern Piedmont, this impact is on both forested and agricultural lands. Additionally, the continued and increasing introduction of exotic and invasive plants, insects, and disease vectors remains a profound threat to forest stability (Thompson et al., 2013).

In the Northern Piedmont, Pinus virginiana (Virginia pine) and Liriodendron tulipifera (tulip-poplar) are common early-successional forest pioneers, especially on uplands. The composition of the more mature forest stands tends to vary with soils, topography, and succession. Dry, nutrient poor sites tend to be dominated by an oak-heath forest community. More mesic sites on soils that have a more basic chemistry tend to support an oak-hickory forest cover. Quercus alba (white oak) is a relative generalist, and it is a common component in all types of upland oak forest of the Northern Piedmont. Quercus rubra (northern red oak) and Quercus velutina (black oak) commonly join the overstory on mesic and submesic sites. Quercus montana (chestnut oak), Quercus coccinea (scarlet oak), and Quercus falcata (southern red oak) prefer drier sites. Quercus stellate (post oak) and Quercus marilandica var. marilandica (blackjack oak) tend to do well on the most drought-prone sites.

Carya (hickories) show a preference for sites that have a higher base saturation, so they are common in both the overstory and understory of the more basic oak-hickory types. Overall species richness tends to be higher on these higher base saturation sites as well. Common constituents include Carya ovata (shagbark hickory), Fraxinus americana (white ash), and Cercis canadensis var. canadensis (eastern redbud). Ericaceous (heather) shrubs tend to be absent on these alkaline sites, but herbaceous species richness tends to be high. Hickories are also common on intermediate oak-hickory sites. The understories, however, are more dominated by Cornus florida (flowering dogwood), Viburnum acerifolium (mapleleaf viburnum), and dry-mesophytic herbaceous generalists.

Most oak-heath forests support few hickories and have few herbaceous species in the understory. These forest communities tend to have an understory dominated by Acer rubrum (red maple), Nyssa sylvatica (blackgum), and deciduous ericad (plants that dislike alkaline soils) shrubs, such as Vaccinium pallidum (early lowbush blueberry), Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry), and other heathers (Virginia DCR, 2016).

In cool, moist ravines that have acidic soils, a mesic mixed hardwood forest of American beech (Fagus grandifolia), white oak, northern red oak, and tulip-poplar is common. This forest community is thought to be replacing upland oak-hickory forests in many areas where fire has been excluded for long periods or where oak recruitment has declined for other reasons (Zimmerman et al., 201). In cool, moist ravines that have more mafic or calcareous substrates, similar mesic mixed hardwood forests also commonly include Fraxinus americana (white ash), Carya cordiformis (bitternut hickory), Tilia americana (basswood), Quercus muehlenbergii (chinquapin oak), Acer saccharum (sugar maple), and dense, species-rich understories where overstory shade is not too extreme.

Riparian forests and flood-plain forests grow widely across the Northern Piedmont. Along larger rivers, these forests tend to be dominated by flood-tolerant trees, such as Acer saccharinum (silver maple), Platanus occidentalis (sycamore), Ulmus americana (American elm), Acer negundo (eastern boxelder), Celtis occidentalis (common hackberry), and Betula nigra (river birch). In high energy environments, these flood-plain forest types are commonly broken by flood-scoured deposition bars, outcrops, and early successional vegetation communities. Along stretches that do not flood as deeply, hydrophytic oaks—such as Quercus palustris (pin oak), Quercus bicolor (swamp white oak), Quercus phellos (willow oak), Quercus lyrata (overcup oak), and Quercus michauxii (swamp chestnut oak)—may dominate the overstory, and Carex (sedges) commonly form large, dense understory communities.

Some additional minor, small-patch forest types (such as eastern white pine-hardwood types and eastern hemlock-hardwood types) and some rock outcrop barrens are scattered across the Northern Piedmont in isolated areas. The eastern hemlock ecological communities are much more consistent with the MLRA concepts of the Northern Blue Ridge and the Ridge and Valley. In the Northern Piedmont, the eastern hemlock communities are thought to represent the last vestiges of a community that is migrating to cooler sites in response to global climate change over the past several thousand years (Virginia DCR, 2016).

Classification relationships

Several modern classification systems for vegetation are used across the United States. The Federal Geographic Data Committee suggests that the U.S. National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) should be the Federal standard. An analysis of the existing vegetation cover using the U.S. Geological Survey, Gap Analysis Program (2011) indicates that the natural vegetation areas in the Northern Piedmont MLRA are predominantly Appalachian-Northeastern Oak-Hardwood-Pine Forest and Woodland (USNVC Macrogroup, 502). A few additional USNVC macrogroups are also present. On a finer scale, USNVC Groups 15 and 650 dominate nearly all site types across the MLRA. This dominance supports the theory that extreme anthropogenic disturbances near the turn of the century significantly homogenized the forests of this region. At any specific field site, existing vegetation may not be a good indication of the best suited potential vegetation. Representative USNVC groups are listed for each ecological site. Groups have been identified by analyzing both existing vegetation cover indicated by GAP/Landfire (USGS, 2011) as well as the vegetation inventory data from the Natural Heritage programs.

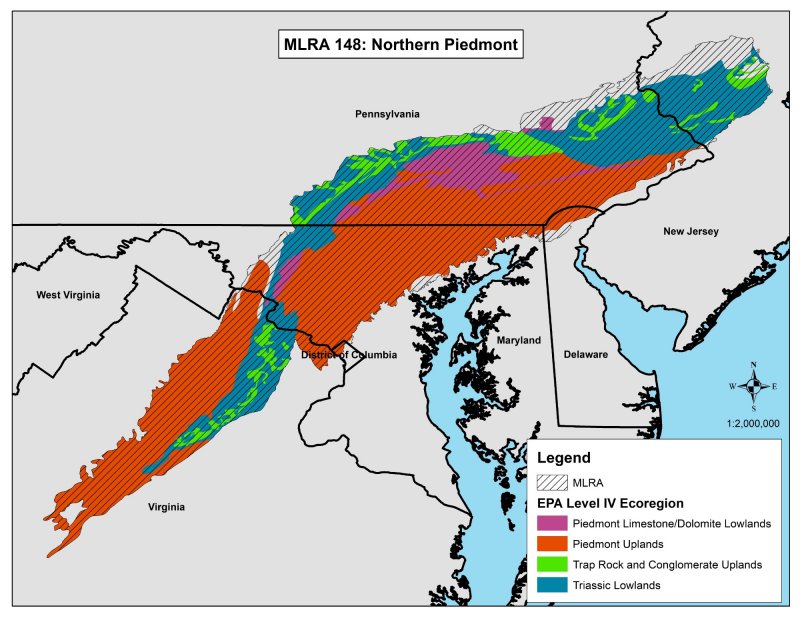

The Northern Piedmont MLRA as defined in USDA Handbook 296 (USDA-NRCS, 2006) very nearly matches the Northern Piedmont Level III Ecoregion as defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The U.S. EPA Level III Ecoregions have also been further subdivided into Level IV Ecoregions. Within MLRA 148 Northern Piedmont, the EPA Level IV Ecoregions are:

• Triassic Lowlands

• Trap Rock (Diabase) and Conglomerate Uplands

• Piedmont Uplands

• Piedmont Limestone/Dolomite Lowlands

• Passaic Basin Freshwater Wetlands

These Level IV Ecoregions explain much of the ecological variation across the MLRA and have been used extensively to assist with defining the Ecological Sites.

Triassic Lowlands

The Triassic Lowlands are dominated by Alfisols derived from Triassic sedimentary rocks. These soils are relatively fertile and typically have a moderate to high level of base saturation in the subsoil. The landscape is comparatively flat and is not highly dissected. The region is characterized by wide undulating ridges; broad, nearly level valleys; and limited local relief. Streams and wetlands are important in the Triassic Lowlands. Wetlands are becoming rarer, especially adjacent to the urban sprawl of megalopolis (Woods et al., 1999).

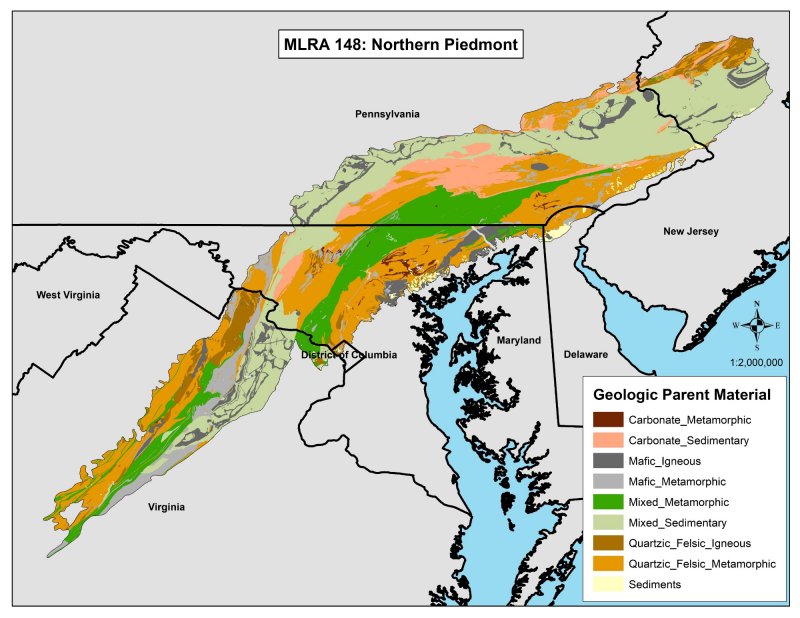

Trap Rock and Conglomerate Uplands

The Trap Rock and Conglomerate Uplands are often also referred to as the Diabase and Conglomerate Uplands. Trap rock is a common term for diabase and other mafic igneous intrusions. This landscape was developed during the Triassic and Jurassic eras as diabase sills, and dikes intruded the sedimentary rocks of the surrounding Triassic Lowlands. The landscape is characterized by wooded, stony hills and steep ridges underlain by a mixture of highly resistant rocks rising relatively sharply above the Triassic Lowlands. The soils are mostly thin (shallow), fine-textured, clayey, non-acidic Alfisols that are hard to till and best suited to forest or pasture. The forests of these uplands are somewhat distinct from those of the rest of the Northern Piedmont because acid loving plants are largely absent, especially on soils derived from diabase. Woodlands continue to be comparatively common in this landscape, especially on steep slopes and in areas where surface rocks and boulders are common (Woods et al., 1999).

Piedmont Uplands

The Piedmont Uplands are dominated by deep Ultisols and Inceptisols that developed from crystalline bedrock. The Piedmont Uplands have substantially higher relief than the Triassic Lowlands. The region is characterized by rounded hills, low ridges, and narrow valleys. The eastern edge of the piedmont creates a relatively abrupt “fall line” as the landscape drops down to the adjacent sediments of the coastal plain. The drop includes high stream gradient, waterfalls, and exposed bedrock. Due to the mixed source materials, the mineralogy of the soils of the Piedmont Uplands varies. The typical piedmont upland is comprised of soils derived from felsic crystalline rocks, but some piedmont soils are derived from more mafic rocks. Some locations have chrome soils derived from ultra-mafic serpentine, which is low in calcium but high in magnesium, chromium, and nickel. Variations in geologic parent material commonly create soils that support corresponding variations in vegetation communities. Serpentine soils support unique “barrens” vegetation communities of oak and pine, greenbrier, and prairie grass (Woods et al., 1999).

Piedmont Limestone/Dolomite Lowlands

The Piedmont Limestone/Dolomite Lowlands are comprised of Hapludalfs derived from carbonate bedrock. Hapludalfs are soils that have a horizon of clay accumulation with a significant decrease in clay content within a depth of 150 centimeters. The soils are potentially highly fertile. The carbonate bedrock weathered to create a landscape of undulating terrain that includes karst features, such as sinkholes, caves, and underground streams. Nearly all the forests on these carbonate lowlands have been replaced by agriculture. This is one of the most productive farming regions of the eastern United States. The predominant natural vegetation community is oak forests dominated by red oak and white oak, but the flora on these basic carbonate soils is distinct from the heath communities on the acidic and less fertile soils of the surrounding areas (Woods et al., 1999).

The Northern Piedmont (MLRA 148) is within the U.S. Forest Service Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province (biome). The Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province is mesophytic and dominated by the drought-resistant oak-hickory forest association, which includes Quercus alba (white oak), Quercus rubra (northern red oak), Quercus falcate (southern red oak), Quercus velutina (black oak), Carya cordiformis (bitternut hickory), and Carya ovata (shagbark hickory). It has well-developed understories of Cornus spp. (dogwood), Sassafras albidum (sassafras), and Carpinus spp. and Ostrya spp. (hornbeam). Ulmus americana (American elm), Liriodendron tulipifera (tuliptree), and Liquidambar styraciflua (sweetgum) are common on somewhat richer sites (Bailey, 1995).

As defined by USDA (USDA-NRCS, 2006), MLRA 148, the Northern Piedmont, coincides well with the U.S. Forest Service ecological section the Northern Appalachian Piedmont. The northwest corner of MLRA 148 also includes a small portion of the Lower New England ecological section (the Reading Prong), where some glacial landforms intermingle with typical piedmont landforms. The main cover types in Northern Appalachian Piedmont Section, as defined by the U.S. Forest Service, are oak-hickory and loblolly-shortleaf pine (McNab et al., 2007).

U.S. Forest Service ecological subsections that coincide with MLRA 148 include the Reading Prong Subsection of the Lower New England Section, the Gettysburg Piedmont Lowland, the Northern Piedmont, the Piedmont Upland, and the Triassic Basins. Note the high level of coincidence between the U.S. Forest Service ecological subsections and the EPA level IV ecoregions.

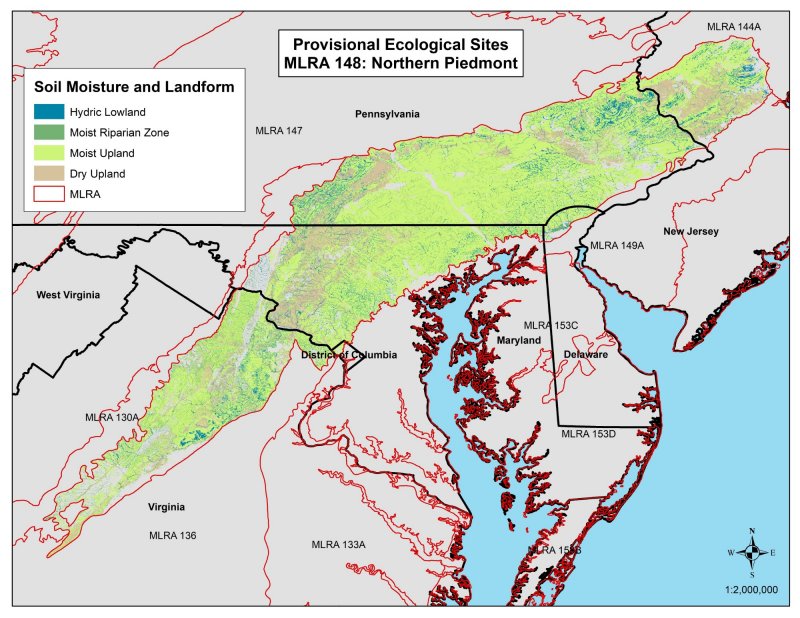

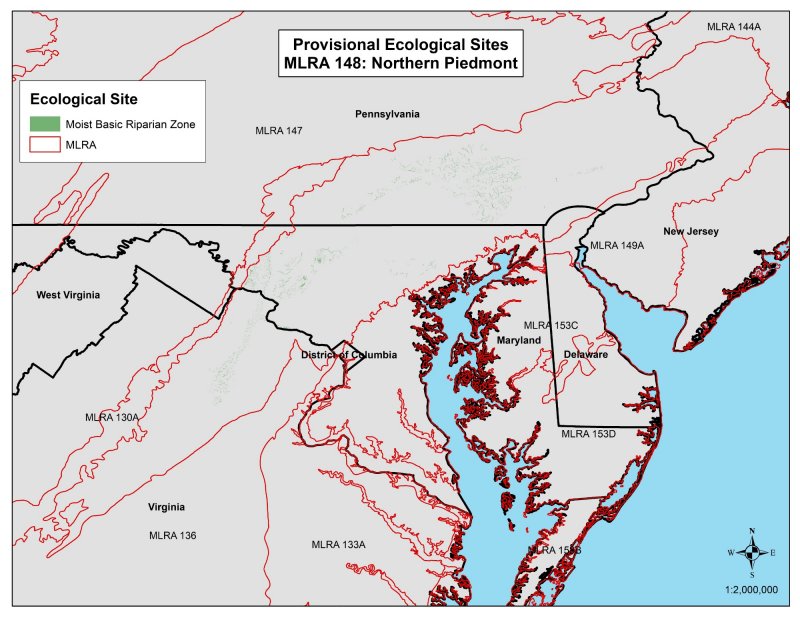

Ecological site concept

This ecological site is highly variable, occupies a variety of landscape positions, and supports a variety of vegetation communities. Riparian zones often possess parent materials from a variety of sources due to the mixing effects of fluvial processes. However, these sites tend to be dominated by circumneautral soils derived from mafic parent materials.

Many vegetation communities on these ecologically mesic riparian sites are also on other riparian ecological sites. The mesic, riparian-zone sites all represent locations where the soils are not hydric and are on flood plains, low terraces, low-order valley bottoms, and adjacent side slopes and are surrounding (but not in) springs, seeps, and stream heads. As such, mesic, riparian-zone sites are ecotonal by definition. They reflect the transition from truly upland to truly hydric lowland. Mesic, riparian-zone sites tend to be in positions that are slightly above the water level where frequency and duration of flooding are lower or in positions where the soils are coarse grained and sufficiently deep to dry out relatively quickly following a flood (Zimmerman et al., 2012).

Distribution of flood energy directly affects particle-size distribution during deposition. The resulting variations in soil texture can significantly affect vegetation communities. The ecologically mesic, riparian-zone sites can occur on soils of any texture, but, when in or adjacent to a perennial stream or river, will often occur on sandy soils or exposed bedrock. The sand can be deep or can be a thin deposit over gravel or cobbles. The mesic sites either do not accumulate fibrous organic material or they accumulate less than the more hydric riparian sites. Accumulation is affected by the persistence of saturation and the strength of flood energy (Zimmerman et al., 2012).

Vegetation communities in the riparian zone are highly influenced by hydrography, especially duration of soil saturation and exposure to flood energy. In very general terms, vegetation communities that are closer to a body of water are likely to be flooded more often and for longer periods of time than those communities that are farther away. Flowing water (streams and rivers) exerts higher energy disturbance than standing water (lakes and ponds). The larger the stream, upstream watershed, valley-or-channel-width restriction, and stream gradient, the greater the increase in frequency, duration, and energy of disturbance of flooding. Regional climate across the Northern Piedmont makes flood-entrained ice (with its unique scouring potential) a notable possibility during winter and spring flooding (Zimmerman et al., 2012).

Due to the ecotonal nature of mesic riparian sites, the vegetation communities are also transitional. Vegetation communities transition from upland communities to wetland communities. As such, these ecological sites display many potential location-specific phases (Zimmerman et al., 2012).

This ecological site corresponds with:

US National Vegetation Classification (USGS, 2011)

• Dominant: Oak-Hickory (USNVC Group 15)

• Bald-cypress–Water Tupelo Floodplain Forest (USNVC Group 33)

• Swamp Chestnut Oak-Laurel Oak-Sweetgum Floodplain Forest (USNVC Group 34)

• Silver Maple-Sugarberry-Sweetgum Floodplain Forest (USNVC Group 673)

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

Not specified |

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.