Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R150AY532TX

Deep Sand

Last updated: 9/22/2023

Accessed: 03/14/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

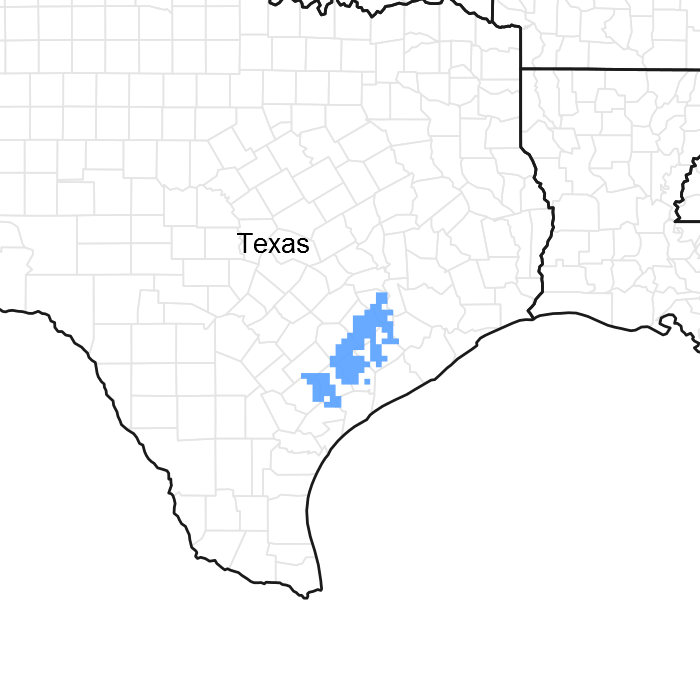

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 150A–Gulf Coast Prairies

MLRA 150A is in the West Gulf Coastal Plain Section of the Coastal Plain Province of the Atlantic Plain in Texas (83 percent) and Louisiana (17 percent). It makes up about 16,365 square miles (42,410 square kilometers). It is characterized by nearly level plains that have low local relief and are dissected by rivers and streams that flow toward the Gulf of Mexico. Elevation ranges from sea level to about 165 feet (0 to 50 meters) along the interior margin. It includes the towns of Crowley, Eunice, and Lake Charles, Louisiana, and Beaumont, Houston, Bay City, Victoria, Corpus Christi, Robstown, and Kingsville, Texas. Interstates 10 and 45 are in the northeastern part of the area, and Interstate 37 is in the southwestern part. U.S. Highways 90 and 190 are in the eastern part, in Louisiana. U.S. Highway 77 passes through Kingsville, Texas. The Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge and the Fannin Battleground State Historic Site are in the part of the area in Texas.

Classification relationships

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006.

-Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 150A

Ecological site concept

The Deep Sand site is characterized by soils with sandy surfaces and subsurfaces greater than 50 inches thick. This site is not similar in soils, landscape positions or vegetation to any other sites in MLRA 150A.

Associated sites

| R150AY535TX |

Southern Loamy Prairie The Southern Loamy Prairie is characterized by very deep loamy soils occurring on uplands. They are vegetatively productive and provide good grazing for livestock. This site is less wooded and more productive than the Deep Sand site. |

|---|---|

| R150AY543TX |

Sandy Prairie The Sandy Prairie site has very deep soils on uplands. The soils are sandy in the upper part from 20 to 50 inches thick overlaying a loamy or clayey subsoil. This site is less wooded and more productive than the Deep Sand site. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Quercus virginiana |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Schizachyrium scoparium |

Physiographic features

These soils are on gently sloping terrace positions near large streams along stream channels and drainageways. Slopes range from 0 to 5 percent, but most are 0 to 2 percent. The elevation is 40 to 250 feet. The soils formed in noncalcareous sandy alluvium that is somewhat modified by wind action.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Coastal plain

> Terrace

|

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to very low |

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 40 – 300 ft |

| Slope | 5% |

| Water table depth | 60 – 72 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate of MLRA 150A is humid subtropical with mild winters. The average annual precipitation in the northern two-thirds of this area is 45 to 63 inches. It is 28 inches at the extreme southern tip of the area and 30 to 45 inches in the southwestern third of the area. The precipitation is fairly evenly distributed, but it is slightly higher in late summer and midsummer in the western part of the area and slightly higher in winter in the eastern part. Rainfall typically occurs as moderate intensity, tropical storms that produce large amounts of rain during the winter. The average annual temperature is 66 to 72 degrees F. The freeze-free period averages 325 days and ranges from 290 to 365 days, increasing in length to the southwest.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 232-259 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 289-365 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 43-50 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 219-265 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 210-365 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 41-56 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 246 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 328 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 47 in |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) HOUSTON HOOKS MEM AP [USW00053910], Tomball, TX

-

(2) VICTORIA RGNL AP [USW00012912], Victoria, TX

-

(3) BAYTOWN [USC00410586], Crosby, TX

-

(4) HOUSTON SUGARLAND MEM [USW00012977], Sugar Land, TX

-

(5) SEALY [USC00418160], Sealy, TX

-

(6) COLUMBUS [USC00411911], Columbus, TX

-

(7) NEW GULF [USC00416286], Boling, TX

-

(8) DANEVANG 1 W [USC00412266], El Campo, TX

-

(9) PIERCE 1 E [USC00417020], El Campo, TX

-

(10) VICTORIA FIRE DEPT #5 [USC00419361], Victoria, TX

Influencing water features

This site is moderately well to somewhat excessively drained. Permeability is moderately slow to rapid.

Wetland description

These soils on this site are non-hydric. Some sites may have small areas that are hydric; these areas are depressional and may hold water for long periods of time. Onsite investigation is necessary to determine exact local conditions.

Soil features

The site is very deep, moderately well to somewhat excessively drained, and moderately to rapidly permeable sands. Soil reaction is moderately acid to neutral. Solum thickness is more than 80 inches. Runoff is negligible on slopes less than 1 percent, very low on 1 to 3 percent slopes, and low on 3 to 5 percent slopes. Soils correlated to this site include: Kuy, and Rupley.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

–

igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rock

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Loamy fine sand (2) Fine sand (3) Sand |

| Family particle size |

(1) Sandy |

| Drainage class | Moderately well drained to somewhat excessively drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow to rapid |

| Soil depth | 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-60in) |

3 – 4 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-60in) |

Not specified |

| Electrical conductivity (0-60in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-60in) |

2 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-60in) |

4.5 – 7.3 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (0-60in) |

3% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (0-60in) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

The Deep Sand ecological site is comprised of small acreage areas dotted across the landscape. They are primarily associated with uplands adjacent to small streams. The soils are very deep sands and are excessively drained. Because of this, they can be quite droughty. The reference plant community is a Tall/Midgrass Savannah Community (1.1) that was in dynamic equilibrium with the ecological forces that formed them. Those forces included grazing by native wild herbivores, natural and anthropogenic fire, and periodic drought and wet cycles. Historically, bison were the primary large ungulate that grazed the site. According to historical accounts, large numbers of bison grazed the Gulf Coast Prairie region. Weniger states, “when DeLeon came looking for LaSalle’s settlement in 1689, he wrote of the area now southern Victoria County as being all very pleasing; and we came across many buffalo.” When back in the same area in 1690 he reported, “we set out in the same direction over some plains which were covered with buffalo, to cross the arroyo of the French (Garcitas Creek).” The typical bison grazing pattern was short, but very intense followed by total deferment until the herds migrated back. Long deferments allowed the tallgrasses to recover carbohydrate reserves and produce a seed crop. A fire regime and frequency of 3 to 8 years, according to Lehmann, is probable and as important as grazing in shaping the plant community.

The reference plant community is a Tall/Midgrass Savannah with a scattered large live oak (Quercus virginiana) and occasional post oak (Quercus stellata). Major tallgrass species included big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), yellow Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and Florida paspalum (Paspalum floridanum). Dominant midgrasses were characterized by little bluestem Schizachyrium scoparium), crinkle awn (Trachypogon spicatus), Texasgrass (Vaseyochloa multinervosa), and Pan American balsamscale (Elionurus tripsacoides). Perennial forbs included purple prairie clover (Dalea purpurea), golden prairie clover (Dalea aurea), snoutbeans (Rhynchosia spp.), sensitive briar (Mimosa microphylla), and woollywhite (Hymenopappus spp). Annual forbs occurred in relatively high numbers in wet years and following intense grazing events by bison. Woody plant encroachment was initially excluded by grassy competition and periodic intense fires.

With the introduction of wild longhorn cattle in the mid-to-late 1700’s, and domestic cattle in the 1820’s, an era of heavy, semi-continuous grazing began. During the Spanish Mission era of the 1600 to 1700’s, in the San Antonio, Goliad, Refugio areas, vast herds of cattle, horses, sheep, and goats were used for meat production for the missions. According to Weniger, “Mission Espiritu Santo, near present Goliad, had a total of 16,000 cattle by 1768.” With no fences, these were free-roaming herds which allowed for escape and population increase in adjacent areas. A further example of large numbers of cattle by Weniger states, “One packery was established at Fulton, Texas in the 1860’s, which slaughtered 40,000 head of cattle during its operation. In the year 1874 alone, 102 million pounds of tallow and over 2.5 million dollars worth of cow hides were shipped from the Texas Coast.” This heavy grazing was exacerbated with the introduction of barbed wire and windmills in the 1880’s. Excessive grazing reduced or eliminated the tallgrass component of the grassland and some midgrasses. As the site transitions, less palatable species such as Pan American balsamscale, brownseed paspalum (Paspalum plicatulum), panicums, and paspalums increased, as did both perennial and annual forbs.

As the tall and midgrasses decrease in composition and biomass production decreases, fuel for fire decreases as well, resulting in less frequent and lower intensity fires. Continuous overuse by livestock and the reduction or cessation of fire allows woody plants to invade. These woody plants include live oak, blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica), post oak, yaupon (Ilex vomitoria), American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana), green briar (Smilax spp.), and mustang grape (Vitis mustangensis). Annual and perennial weeds also increase significantly.

As state and transition thresholds are crossed, changes occur impacting plant composition, biomass production, litter accumulation, water infiltration, and water storage. These changes impact other natural ecological functions such as frequency and intensity of fire. The result converts the site from a true Tall/Midgrass Savannah to an Oak Woodland in most instances. In the heavily wooded state, canopy cover may exceed 100 percent due to the various layers of trees, shrubs, and woody vines. Herbaceous production may be totally eliminated. Once these thresholds have been crossed, restoration back to the reference plant community becomes much more difficult and expensive. Even though the plant community may be restored through the use of a combination of practices such as mechanical and herbicidal brush management, prescribed grazing and fire, this community cannot be maintained without the continuous use of these tools on a frequent basis.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time |

|---|---|---|

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of fire and regular disturbance return intervals |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Savannah

Dominant plant species

-

live oak (Quercus virginiana), tree

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

Community 1.1

Tall/Midgrass Savannah

The reference plant community for the Deep Sand Site is a Tall/Midgrass Savannah Community (1.1) with a less than 15 percent canopy of primarily live oak trees. Tallgrasses most likely made up over 60 percent of herbaceous production, followed by midgrasses, shortgrasses, and forbs. Dominant tallgrasses included big bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, and switchgrass. Midgrasses such as little bluestem, Texasgrass, crinkleawn, and Pan American balsamscale made up a significant portion of the herbaceous composition. Perennial forbs such as prairie clover, sensitive briar, and woollywhite are important contributors. Annual forbs occur differing amounts in response to grazing intensity, fire, drought, or excessive precipitation. This savannah site was periodically heavily grazed by bison and both wild and domestic livestock. Continuous heavy grazing came with the advent of barbed wire and windmills in the mid to late 1800’s. Overgrazing initially resulted in the reduction and then loss of the tallgrass component, creating loss of total biomass, reduced litter accumulations and reduction of fire frequency and intensity. If overgrazing continues, midgrasses replace tallgrasses, and some shortgrasses and annual forbs begin to dominate the community resulting in the Mid/Shortgrass Savannah Community (1.2).

Figure 8. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 1450 | 2900 | 4200 |

| Forb | 100 | 150 | 200 |

| Tree | 100 | 150 | 200 |

| Shrub/Vine | 50 | 75 | 100 |

| Total | 1700 | 3275 | 4700 |

Figure 9. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX7606, Tall/Midgrass Prairie Community. Prairie Community composed of warm-season tall and midgrasses..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 24 | 23 | 8 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

Community 1.2

Mid/Shortgrass Savannah

This community is still a part of the reference state because remnants of some of the tallgrasses remain. However, this is now a midgrass dominant community, with higher amounts of shortgrasses and forbs. This community will be dominated by such species as little bluestem, Texasgrass, brownseed paspalum, broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus), and Pan American balsamscale. The perennial and annual forb community will be more evident because of reduced competition for sunlight and moisture. Forbs like purple and golden prairie clover, woollywhite, snoutbeans, and sensitive briars will be much more common. Woody species such as post oak and blackjack oak, American beautyberry, and yaupon also begin to increase.

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Heavy grazing, lack of fire, and no brush management transition this site to Community 1.2.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

This community develops as a result of heavy grazing. The litter accumulation is reduced along with fine-fuel loads resulting in reduced fire intensity. This community can be converted relatively easily back to community 1.1 through the use of prescribed grazing, brush management, and prescribed burning. Brush management associated with restoration back to community 1.1 would typically be individual plant treatment (IPT).

State 2

Woodland

Dominant plant species

-

live oak (Quercus virginiana), tree

-

post oak (Quercus stellata), tree

Community 2.1

Semi-Wooded Grassland

This community is created by excessive continuous grazing which removes the tallgrass component and greatly reduces the midgrass community. Big bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, and other tallgrasses are non-existent. Little bluestem, crinkleawn, and brownseed paspalum are found only in isolated scattered clumps. Shade tolerant species such as Texasgrass and purpletop (Tridens flavus) are present. Once canopy cover approaches 30 percent, shade becomes a major driver to the herbaceous plant composition. The canopy will continue to increase regardless of grazing management. Litter and plant biomass are greatly reduced, thus significantly reducing fire frequency and intensity and allowing woody plants to increase. The grass community is dominated by Chloris species, fringeleaf paspalum (Paspalum setaceum), Scribner’s rosettegrass (Dicanthelium oligasanthes), purple three-awn (Aristida purpurea), panicums, and paspalums. Within the woody canopy such shade tolerant species as purpletop and Texasgrass still remain. Both perennial and annual forbs such as prairie clovers, snoutbean, woollywhite, sensitive briar, croton (Croton spp.), partridgepea (Chamaecrista fasciculata), frostweed (Helianthemum spp.), and many others become much more prevalent. Trees, shrubs, and vines have increased drastically and, in some places, form dense mottes. Blackjack and post oak now co-habit with live oak and understory/overstory shrubs and vines such as American beautyberry, yaupon, mustang grape, and poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) are very common.

Community 2.2

Oak Woodland

This community is now a closed canopy of hardwood trees, shrubs, and woody vines. It is a result of continued heavy grazing, no fire, and no brush management. At this point, there is almost no herbaceous production on the soil surface due to lack of sunlight. Oaks, yaupon, beautyberry, mustang grape, and poison ivy dominate. Fire is no longer an option unless leaf litter is burned following leaf fall. Multiple burns over time will be needed to restore grasses back into this plant community. Grazeable herbaceous forage in this community is non-existent.

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Continued heavy grazing, lack of brush management, and lack of fire transition this site to Community 2.2.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

This community can be restored back to community 2.1 or 1.2 with massive inputs of capital and labor. Mechanical and/or herbicidal brush management must be employed followed by prescribed burning and prescribed grazing. Due to residual woody seed sources and introduction of seed from adjacent sites by wildlife, continual inputs of herbicide and fire must be utilized to maintain this site once initial brush management is completed.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Continued heavy grazing, lack of fire, and lack of brush management transition the site to State 2. This is evident once the woody canopy is greater than 30 percent.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

State 2 can be taken back to community 1.2 or possibly 1.1, but not without major inputs of energy and capital in the form of brush management, prescribed fire, and prescribed grazing. Once in this state, continual input will be required to convert to community 1.2 in order to maintain a Savannah State (1).

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 0 | Tallgrass | 400–700 | ||||

| 1 | Tallgrasses | 800–3950 | ||||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 500–1800 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 800–950 | – | ||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 400–700 | – | ||

| Florida paspalum | PAFL4 | Paspalum floridanum | 250–600 | – | ||

| 2 | Tall/midgrasses | 350–550 | ||||

| Pan American balsamscale | ELTR4 | Elionurus tripsacoides | 100–350 | – | ||

| purpletop tridens | TRFL2 | Tridens flavus | 100–250 | – | ||

| Texasgrass | VAMU | Vaseyochloa multinervosa | 100–250 | – | ||

| spiked crinkleawn | TRSP12 | Trachypogon spicatus | 75–200 | – | ||

| 3 | Midgrasses | 200–400 | ||||

| brownseed paspalum | PAPL3 | Paspalum plicatulum | 75–200 | – | ||

| longspike tridens | TRST2 | Tridens strictus | 50–150 | – | ||

| broomsedge bluestem | ANVI2 | Andropogon virginicus | 50–150 | – | ||

| purple threeawn | ARPU9 | Aristida purpurea | 25–75 | – | ||

| 4 | Shortgrasses | 100–200 | ||||

| hooded windmill grass | CHCU2 | Chloris cucullata | 50–75 | – | ||

| windmill grass | CHLOR | Chloris | 25–50 | – | ||

| Scribner's rosette grass | DIOLS | Dichanthelium oligosanthes var. scribnerianum | 25–50 | – | ||

| thin paspalum | PASE5 | Paspalum setaceum | 5–50 | – | ||

| fall witchgrass | DICO6 | Digitaria cognata | 5–25 | – | ||

| crowngrass | PASPA2 | Paspalum | 5–20 | – | ||

| panicgrass | PANIC | Panicum | 5–20 | – | ||

| red grama | BOTR2 | Bouteloua trifida | 0–15 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 5 | Forbs | 100–200 | ||||

| Kairn's sensitive-briar | MILA15 | Mimosa latidens | 5–15 | – | ||

| powderpuff | MIST2 | Mimosa strigillosa | 5–15 | – | ||

| Carolina woollywhite | HYSC | Hymenopappus scabiosaeus | 5–15 | – | ||

| hogwort | CRCA6 | Croton capitatus | 0–10 | – | ||

| golden prairie clover | DAAU | Dalea aurea | 5–10 | – | ||

| purple prairie clover | DAPU5 | Dalea purpurea | 5–10 | – | ||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 5–10 | – | ||

| bluestem pricklypoppy | ARAL3 | Argemone albiflora | 5–10 | – | ||

| purple poppymallow | CAIN2 | Callirhoe involucrata | 5–10 | – | ||

| partridge pea | CHFA2 | Chamaecrista fasciculata | 5–10 | – | ||

| Texas bullnettle | CNTE | Cnidoscolus texanus | 5–10 | – | ||

| Texas lupine | LUTE | Lupinus texensis | 5–10 | – | ||

| wax mallow | MAARD | Malvaviscus arboreus var. drummondii | 5–10 | – | ||

| groundcherry | PHYSA | Physalis | 5–10 | – | ||

| queen's-delight | STSY | Stillingia sylvatica | 1–10 | – | ||

| stemless spiderwort | TRSU | Tradescantia subacaulis | 5–10 | – | ||

| Texas vervain | VEHA | Verbena halei | 1–5 | – | ||

| American snoutbean | RHAM | Rhynchosia americana | 2–5 | – | ||

| Texas snoutbean | RHSE4 | Rhynchosia senna | 2–5 | – | ||

| fanpetals | SIDA | Sida | 1–5 | – | ||

| evening primrose | OENOT | Oenothera | 0–5 | – | ||

| woodsorrel | OXALI | Oxalis | 1–5 | – | ||

| phlox | PHLOX | Phlox | 1–5 | – | ||

| Texas bindweed | COEQ | Convolvulus equitans | 0–5 | – | ||

| low silverbush | ARHU5 | Argythamnia humilis | 0–5 | – | ||

| cardinal's feather | ACRA | Acalypha radians | 2–5 | – | ||

| Engelmann's daisy | ENPE4 | Engelmannia peristenia | 0–5 | – | ||

| buckwheat | ERIOG | Eriogonum | 2–5 | – | ||

| slender dwarf morning-glory | EVAL | Evolvulus alsinoides | 1–5 | – | ||

| Texas croton | CRTE4 | Croton texensis | 0–5 | – | ||

| Torrey's tievine | IPCOT | Ipomoea cordatotriloba var. torreyana | 0–5 | – | ||

| sand phacelia | PHPA4 | Phacelia patuliflora | 1–4 | – | ||

| viperina | ZOBR | Zornia bracteata | 1–3 | – | ||

| coastal indigo | INMI | Indigofera miniata | 1–3 | – | ||

| hoary milkpea | GACA | Galactia canescens | 1–3 | – | ||

| geranium | GERAN | Geranium | 0–2 | – | ||

| bristly nama | NAHI | Nama hispidum | 0–2 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 6 | Shrubs/Vines | 50–100 | ||||

| mustang grape | VIMU2 | Vitis mustangensis | 50–100 | – | ||

| American beautyberry | CAAM2 | Callicarpa americana | 10–50 | – | ||

| yaupon | ILVO | Ilex vomitoria | 10–50 | – | ||

| eastern poison ivy | TORAR | Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans | 25–50 | – | ||

| pricklypear | OPUNT | Opuntia | 5–15 | – | ||

| blackberry | RUBUS | Rubus | 5–15 | – | ||

| greenbrier | SMILA2 | Smilax | 5–10 | – | ||

| Carolina coralbead | COCA | Cocculus carolinus | 5–10 | – | ||

| yucca | YUCCA | Yucca | 0–10 | – | ||

|

Tree

|

||||||

| 7 | Trees | 100–200 | ||||

| live oak | QUVI | Quercus virginiana | 50–200 | – | ||

| post oak | QUST | Quercus stellata | 25–50 | – | ||

| blackjack oak | QUMA3 | Quercus marilandica | 25–50 | – | ||

| water oak | QUNI | Quercus nigra | 5–40 | – | ||

| honey mesquite | PRGL2 | Prosopis glandulosa | 1–40 | – | ||

| wingleaf soapberry | SASA4 | Sapindus saponaria | 5–30 | – | ||

| lime pricklyash | ZAFA | Zanthoxylum fagara | 1–30 | – | ||

| sweet acacia | ACFA | Acacia farnesiana | 0–30 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

The Coastal Prairie communities support a wide array of animals. Cattle and many species of wildlife make extensive use of the site. White-tailed deer may be found scattered across the prairie and are found in heavier concentrations where woody cover exists. Feral hogs are present and at times abundant. Coyotes are abundant and fill the mammalian predator niche. Rodent populations rise during drier periods and fall during periods of inundation. Attwater’s pocket gophers are abundant and have an important impact on the ecology of the site. The badger is present but not abundant in locations at the southern extent of the site. Locally unique species alligators and bullfrogs.

The region is a major flyway for waterfowl and migrating birds. Hundreds of thousands of ducks, geese, and sandhill cranes abound during winter. Two important endangered species occur in the area, the whooping crane and Attwater’s prairie chicken. Many other species of avian predators including northern harriers, ferruginous hawks, red-tailed hawks, white-tailed kites, kestrels, and, occasionally, swallow-tailed kites utilize the vast grasslands. Many species of grassland birds use the site, including blue grosbeaks, dickcissels, eastern meadowlarks, several sparrows, including, vesper sparrow, lark sparrow, savannah sparrow, grasshopper sparrow, and Le Conte’s sparrow.

Hydrological functions

The Savannah and Woodland States use all the water from rainfall events that occur. Research has shown that the evapotranspiration rate on the across all communities is nearly the same.

Recreational uses

White-tailed deer, Rio Grande turkey, and feral hogs are hunted on the site. This site may also be used for bird watching. In the wooded state, this site makes ideal campgrounds if a limited amount of woody vegetation is removed.

Wood products

In the Woodland State, this site produces an abundance of oak firewood.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

This site description was developed as part of the provisional ecological site initiative using historic soil survey manuscripts, available range site descriptions, and low intensity field sampling.

Other references

Allain, L., L. Smith, C. Allen, M. Vidrine, and J. B. Grace. 2006. A floristic quality assessment system for the Coastal Prairie of Louisiana. North American Prairie Conference, 19.

Allain, L., M. Vidrine, V. Grafe, C. Allen, and S. Johnson. 2000. Paradise lost: The coastal prairie of Louisiana and Texas. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Layfayette, LA.

Archer, S. 1994. Woody plant encroachment into southwestern grasslands and savannas: rates, patterns and proximate causes. Ecological implications of livestock herbivory in the West, 13-68.

Archer, S. 1995. Herbivore mediation of grass-woody plant interactions. Tropical Grasslands, 29:218-235.

Archer, S. 1995. Tree-grass dynamics in a Prosopis-thornscrub savanna parkland: reconstructing the past and predicting the future. Ecoscience, 2:83-99.

Archer, S. and F. E. Smeins. 1991. Ecosystem-level processes. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heischmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Baen, J. S. 1997. The growing importance and value implications of recreational hunting leases to agricultural land investors. Journal of Real Estate Research, 14:399-414.

Bailey, V. 1905. North American Fauna No. 25: Biological Survey of Texas. United States Department of Agriculture Biological Survey. Government Printing Office, Washington D. C.

Baldwin, H. Q., J. B. Grace, W. C. Barrow, and F. C. Rohwer. 2007. Habitat relationships of birds overwintering in a managed coastal prairie. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 119(2):189-198.

Beasom, S. L, G. Proudfoot, and J. Mays. 1994. Characteristics of a live oak-dominated area on the eastern South Texas Sand Plain. In the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute Annual Report, 1-2.

Berlandier, J. L. 1980. Journey to Mexico during the years 1826 to 1834: translated. Texas State Historical Associated and the University of Texas. Austin, TX.

Bestelmeyer, B. T., J. R. Brown, K. M. Havstad, R. Alexander, G. Chavez, and J. E. Herrick. 2003. Development and use of state-and-transition models for rangelands. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):114-126.

Bollaert, W. 1956. William Bollaert’s Texas. Edited by W. E. Hollon and R. L. Butler. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK.

Bonnell, G. W. 1840. Topographical description of Texas: To which is added, an account of the Indian tribes. Clark, Wing, and Brown, Austin, TX.

Box, T. W. 1960. Herbage production on four range plant communities in South Texas. Journal of Range Management, 13:72-76.

Box, T. W. and A. D. Chamrad. 1966. Plant communities of the Welder Wildlife Refuge.

Briske, B. B, B. T. Bestelmeyer, T. K. Stringham, and P. L. Shaver. 2008. Recommendations for development of resilience-based State-and-Transition Models. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 61:359-367.

Brite, T. R. 1860. Atascosa County. The Texas Almanac for 1861. Richardson and Co., Galveston, TX.

Brown, J. R. and S. Archer. 1999. Shrub invasion of grassland: recruitment is continuous and not regulated by herbaceous biomass or density. Ecology, 80(7):2385-2396.

Chamrad, A. D. and J. D. Dodd. 1972. Prescribed burning and grazing for prairie chicken habitat manipulation in the Texas coastal prairie. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 12:257-276.

Crawford, J. T. 1912. Correspondence from the British archives concerning Texas, 1837-1846. Edited by E. D. Adams. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 15:205-209.

Davis, R. B. and R. L. Spicer. 1965. Status of the practice of brush control in the Rio Grande Plain. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Bulletin, 46.

Davis, W. B. 1974. The Mammals of Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Bulletin, 41.

Diamond, D. D. and T. E. Fulbright. 1990. Contemporary plant communities of upland grasslands of the Coastal Sand Plain, Texas. Southwestern Naturalist, 35:385-392.

Dillehay, T. 1974. Late quaternary bison population changes on the Southern Plains. Plains Anthropologist, 19:180-96.

Drawe, D. L., A. D. Chamrad, and T. W. Box. 1978. Plant communities of the Welder Wildlife Refuge.

Drawe, D. L. and T. W. Box. 1969. High rates of nitrogen fertilization influence Coastal Prairie range. Journal of Range Management, 22:32-36.

Edward, D. B. 1836. The history of Texas; or, the immigrants, farmers, and politicians guide to the character, climate, soil and production of that country. Geographically arranged from personal observation and experience. J. A. James and Co., Cincinnati, OH.

Everitt, J. H. and M. A. Alaniz. 1980. Fall and winter diets of feral pigs in south Texas. Journal of Range Management, 33:126-129.

Everitt, J. H. and D. L. Drawe. 1993. Trees, shrubs and cacti of South Texas. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, TX.

Everitt, J. H., D. L. Drawe, and R. I. Lonard. 1999. Field guide to the broad-leaved herbaceous plants of South Texas used by livestock and wildlife. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, TX.

Foster, J. H. 1917. Pre-settlement fire frequency regions of the United States: A first approximation. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 20.

Foster, W. C. 2010. Spanish Expeditions into Texas 1689-1768. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Frost, C. C. 1995. Presettlement fire regimes in southeastern marshes, peatlands, and swamps. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 19:39-60.

Frost, C. C. 1998. Presettlement fire frequency regimes of the United States: A first approximation. Fire in ecosystem management: Shifting the paradigm from suppression to prescription. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 20:70-81.

Fulbright, T. E. and S. L. Beasom. 1987. Long-term effects of mechanical treatment on white-tailed deer browse. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 15:560-564.

Fulbright, T. E., D. D. Diamond, J. Rappole, and J. Norwine. 1990. The Coastal Sand Plain of Southern Texas. Rangelands, 12:337-340.

Fulbright, T. E., J. A. Ortega-Santos, A. Lozano-Cavazos, and L. E. Ramirez-Yanez. 2006. Establishing vegetation on migrating inland sand dunes in Texas. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 59:549-556.

Gould, F. W. 1975. The Grasses of Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Grace, J. B., T. M. Anderson, M. D. Smith, E. Seabloom, S. J. Andelman, G. Meche, E. Weiher, L. K. Allain, H. Jutila, M. Sankaran, J. Knops, M. Ritchie, and M. R. Willig. 2007. Does species diversity limit productivity in natural grassland communities? Ecology Letters, 10(8):680-689.

Grace, J. B., L. K. Allain, H. Q. Baldwin, A. G. Billock, W. R. Eddleman, A. M. Given, C. W. Jeske, and R. Moss. 2005. Effects of prescribed fire in the coastal prairies of Texas. USGS Open File Report, 2005-1287.

Grace, J. B., L. Allain, C. Allen. 2000. Factors associated with plant species richness in a coastal tall-grass prairie. Journal of Vegetation Science, 11:443-452.

Graham, D. 2003. Kings of Texas: The 150-year saga of an American ranching empire. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Hamilton, W. and D. Ueckert. 2005. Rangeland woody plant control: Past, present, and future. Brush management: Past, present, and future, 3-16.

Hansmire, J. A., D. L. Drawe, B. B. Wester, and C. M. Britton. 1988. Effect of winter burns on forbs and grasses of the Texas Coastal Prairie. The Southwestern Naturalist, 33(3):333-338.

Harcombe, P. A. and J. E. Neaville. 1997. Vegetation types of Chambers County, Texas. The Texas Journal of Science, 29:209-234.

Hatch, S. L., J. L. Schuster, and D. L. Drawe. 1999. Grasses of the Texas Gulf Prairies and Marshes. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Heitschmidt, R. K. and J. W. Stuth. 1991. Grazing management: An ecological perspective. Timberline Press, Portland, OR.

Hughes, G.U. 1846. Memoir Description of a March of a Division of the United States Army under the Command of Brigadier General John E. Wool, From San Antonio de Bexar, in Texas to Saltillo, in Mexico. Senate Executive Document, 32.

Inglis, J. M. 1964. A history of vegetation of the Rio Grande Plains. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Bulletin, 45.

Jenkins, J. H. 1973. The Papers of the Texas Revolution, 1835-1836. Presidential Press, Austin, TX.

Johnson, M. C. 1963. Past and present grasslands of southern Texas and northeastern Mexico. Ecology 44(3):456-466.

Joutel, H. 1906. Joutel’s journal of La Salle’s last voyage, 1686-1687. Edited by H. R. Stiles. Joseph McDonough, Albany, NY.

Kennedy, W. 1841. Texas: The rise, progress, and prospects of the Republic of Texas. Lincoln’s Inn, London, England.

Kimmel, F. 2008. Louisiana's Cajun Prairie: An endangered ecosystem. Louisiana Conservationist, 61(3):4-7.

Le Houerou, H. N. and J. Norwine. 1988. The ecoclimatology of South Texas. In Arid lands: today and tomorrow. Edited by E. E. Whitehead, C. F. Hutchinson, B. N. Timmesman, and R. G. Varady, 417-444. Westview Press, Boulder, CO.

Lehman, V. W. 1965. Fire in the range of Attwater’s prairie chicken. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 4:127-143.

Lehman, V. W. 1969. Forgotten Legions: Sheep in the Rio Grande Plain of Texas. Texas Western Press, El Paso, TX.

Lusk, R. M. 1917. A history of Constantine Lodge, No. 13, ancient free, and accepted Masons, Bonham, Texas. Favorite Printing Co., Hilbert, WI.

McDanield, H. F. and N. A. Taylor. 1877. The coming empire, or, two thousand miles in Texas on horseback. A. S. Barnes & Company, New York, NY.

McGinty A. and D. N. Ueckert. 2001. The brush busters success story. Rangelands, 23:3-8.

McLendon, T. 1991. Preliminary description of the vegetation of south Texas exclusive of coastal saline zones. Texas Journal of Science, 43:13-32.

Mutz, J. L., T. J. Greene, C. J. Scifres, and B. H. Koerth. 1985. Response of Pan American balsamscale, soil, and livestock to prescribed burning. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, B-1492.

Norwine, J. 1978. Twentieth-century semiarid climates and climatic fluctuations in Texas and northeastern Mexico. Journal of Arid Environments, 1:313-325.

Norwine, J. and R. Bingham. 1986. Frequency and severity of droughts in South Texas: 1900-1983, 1-17. Livestock and wildlife management during drought. Edited by R. D. Brown. Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Kingsville, TX.

Olmsted, F. L. 1857. A journey through Texas, or a saddle trip on the Southwest frontier: with a statistical appendix. Dix, Edwards, and co., New York, London.

Palmer, G. R., T. E. Fulbright, and G. McBryde. 1995. Inland sand dune reclamation on the Coastal Sand Plain of Southern Texas. Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute Annual Report, 30-31.

Pickens, B., S. L. King, B. Vermillion, L. M. Smith, and L. Allain. 2009. Conservation Planning for the Coastal Prairie Region of Louisiana. A final report from Louisiana State University to the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Prichard, D. 1998. Riparian area management: A user guide to assessing proper functioning condition and the supporting science for lotic areas. Bureau of Land Management, Denver, CO.

Rappole, J. H. and G. W. Blacklock. 1994. A field guide: Birds of Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Rappole, J. H. and G. W. Blacklock. 1985. Birds of the Texas Coastal Bend: Abundance and distribution. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Rhyne, M. Z. 1998. Optimization of wildlife and recreation earnings for private landowners. M. S. Thesis, Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Kingsville, TX.

Schindler, J. R. and T. E. Fulbright. 2003. Roller chopping effects on Tamaulipan scrub community composition. Journal of Range Management, 56:585-590.

Schmidley, D. J. 1983. Texas mammals east of the Balcones Fault zone. Texas A&M University Press. College Station, TX.

Scifres C. J., W. T. Hamilton, J. R. Conner, J. M. Inglis, and G. A. Rasmussen. 1985. Integrated Brush Management Systems for South Texas: Development and Implementation. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, College Station, TX.

Scifres, C. J. 1975. Systems for improving McCartney rose infested coastal prairie rangeland. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, MP 1225.

Scifres, C. J. and W. T. Hamilton. 1993. Prescribed burning for brushland management: The South Texas example. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX.

Shelby, C. 1933. Letters of an early American traveler: Mary Austin Holley, her life and her works, 1784-1846. Southwest Press, Dallas, TX.

Siemann, E., and W. E. Rogers. 2007. The role of soil resources in an exotic tree invasion in Texas coastal prairie. Journal of Ecology, 95(4):689-697.

Smith, L. M. 1996. The rare and sensitive natural wetland plant communities of interior Louisiana. Louisiana Natural Heritage Program, Baton Rouge, LA.

Smeins, F. E., D. D. Diamond, and W. Hanselka. 1991. Coastal prairie, 269-290. Ecosystems of the World: Natural Grasslands. Edited by R. T. Coupland. Elsevier Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Stringham, T. K., W. C. Krueger, and P. L. Shaver. 2001. State and transition modeling: An ecological process approach. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):106-113.

Stutzenbaker, C. D. 1999. Aquatic and wetland plants of the Western Gulf Coast. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Tharp, B. C. 1926. Structure of Texas vegetation east of the 98th meridian. University of Texas Bulletin, 2606.

Urbatsch, L. 2000. Chinese tallow tree Triadica sebifera (L.) Small. USDA-NRCS, National Plant Center, Baton Rouge, LA.

Van’t Hul, J. T., R. S. Lutz, and N. E. Mathews. 1997. Impact of prescribed burning on vegetation and bird abundance on Matagorda Island, Texas. Journal of Range Management, 50:346-360.

Vidrine, M. F. 2010. The Cajun Prairie: A natural history. Cajun Prairie Habitat Preservation Society, Eunice, LA.

Vines, R. A. 1984. Trees of Central Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Vines, R. A. 1977. Trees of Eastern Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Warren, W. S. 1998. The La Salle Expedition to Texas: The journal of Henry Joutel, 1684-1687. Edited by W. C. Foster. Texas State Historical Association, Austin, TX.

Wade, D. D., B. L. Brock, P. H. Brose, J. B. Grace, G. A. Hoch, and W. A. Patterson III. 2000. Fire in Eastern ecosystems. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora. Edited by. J. K. Brown and J. Kaplers. United States Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden, UT.

Weaver, J. E. and F. E. Clements. 1938. Plant ecology. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Whittaker, R. H., L. E. Gilbert, and J. H. Connell. 1979. Analysis of a two-phase pattern in a mesquite grassland, Texas. Journal of Ecology, 67:935-52.

Wilbarger, J. W. 1889. Indian depredation in Texas. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Scotts Valley, CA.

Williams, L. R. and G. N Cameron. 1985. Effects of removal of pocket gophers on a Texas coastal prairie. The American Midland Naturalist Journal, 115:216-224.

Woodin, M. C., M. K. Skoruppa, and G. C. Hickman. 2000. Surveys of night birds along the Rio Grande in Webb County, Texas. Final Report, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Corpus Christi, TX.

Wright, H.A. and A.W. Bailey. 1982. Fire Ecology: United States and Southern Canada. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Contributors

Stan Reinke, SR Ecological Services, Victoria, TX

Dan Caudle, Natural Resources Management, Weatherford, TX

Approval

Bryan Christensen, 9/22/2023

Acknowledgments

Reviewers:

Justin Clary, RMS, NRCS, Temple, TX

Shanna Dunn, RSS, NRCS, Corpus Christi, TX

Vivian Garcia, RMS, NRCS, Corpus Christi, TX

Jason Hohlt, RMS, NRCS, Kingsville, TX

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Vivian Garcia, Zone RMS, NRCS, Corpus Christi, TX |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | 361-241-0609 |

| Date | 03/27/2008 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Uncommon. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

Uncommon. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Expect no more than 30 percent bare ground distributed in small patches. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

None. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

This site has highly permeable soils with high infiltration rates. Only small-sized litter will move short distances during intense storms. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil surface is resistant to erosion. Stability class range is expected to be 2 to 3. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

40 to 78 inches thick with light brownish gray to very pale brown loamy fine sand, weak medium subangular blocky structure, loose, very friable, common fine roots, and clear smooth boundary. SOM is 0.5 to 1.0 percent. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

Under reference conditions, the savannah of trees, shrubs, vines, grasses, and forbs along with adequate litter and little bare ground provides for maximum infiltration and little runoff under normal rainfall events. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm-season tallgrassesSub-dominant:

Warm-season midgrasses TreesOther:

Shrubs/Vines ForbsAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

There should be little mortality or decadence for any functional group of the reference community. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Litter is primarily herbaceous. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

2,000 to 4,500 pounds per acre. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Bahiagrass, post oak, blackjack oak, American beautyberry, and yaupon. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All plants should be capable of reproduction except during periods of prolonged drought conditions, heavy natural herbivory, or intense wildfires.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Absence of disturbance and natural regeneration over time |

|---|---|---|

| R2A | - | Reintroduction of fire and regular disturbance return intervals |