Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R150BY668TX

Salty Bottomland

Last updated: 9/22/2023

Accessed: 03/03/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

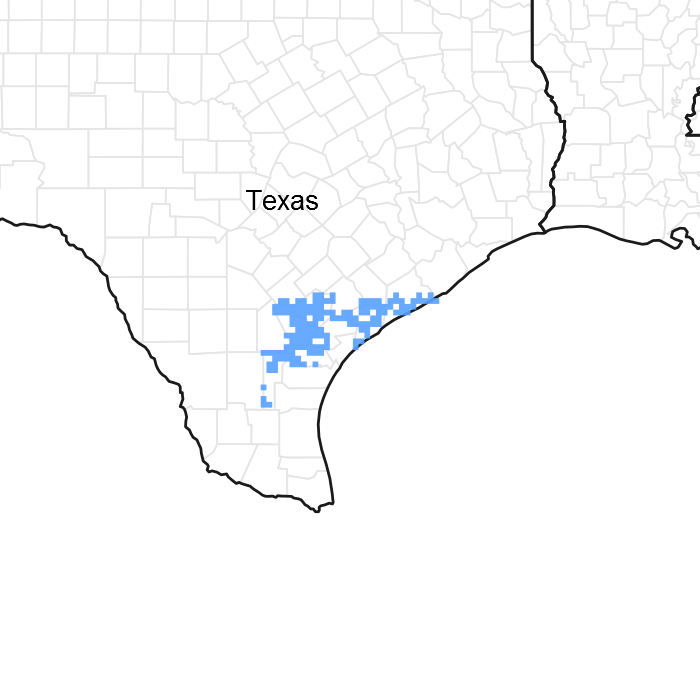

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 150B–Gulf Coast Saline Prairies

MLRA 150B is in the West Gulf Coastal Plain Section of the Coastal Plain Province of the Atlantic Plain and entirely in Texas. It makes up about 3,420 square miles. It is characterized by nearly level to gently sloping coastal lowland plains dissected by rivers and streams that flow toward the Gulf of Mexico. Barrier islands and coastal beaches are included. The lowest parts of the area are covered by high tides, and the rest are periodically covered by storm tides. Parts of the area have been worked by wind, and the sandy areas have gently undulating to irregular topography because of low mounds or dunes. Broad, shallow flood plains are along streams flowing into the bays. Elevation generally ranges from sea level to about 10 feet, but it is as much as 25 feet on some of the dunes. Local relief is mainly less than 3 feet. The towns of Groves, Texas City, Galveston, Lake Jackson, and Freeport are in the northern half of this area. The towns of South Padre Island, Loyola Beach, Corpus Christi, and Port Lavaca are in the southern half. Interstate 37 terminates in Corpus Christi, and Interstate 45 terminates in Galveston.

Classification relationships

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006.

-Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 150B

Ecological site concept

Salty Bottomlands occupy the mouths of rivers as they enter the Gulf of Mexico. It is an alluvial, bottomland floodplain that is influenced by the interaction of freshwater inflows from the river and tidal waters. The tidal waters are saline and exert a strong influence on the vegetation of the area as they mix with freshwater inflows to produce varying conditions from nearly fresh to saline.

Associated sites

| R150BY652TX |

Southern Salt Marsh This site is on a lower landform closer to the bay and is wetter. |

|---|---|

| R150BY551TX |

Salty Prairie This site is on flats outside of the floodplain. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Spartina spartinae |

Physiographic features

Salty Bottomlands occupy the mouths of rivers as they enter the Gulf of Mexico. It is an alluvial, bottomland floodplain that is influenced by the interaction of freshwater inflows from the river and tidal waters. Slopes range from 0 to 1 percent.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Coastal plain

> Flood plain

|

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to high |

| Flooding duration | Brief (2 to 7 days) to long (7 to 30 days) |

| Flooding frequency | Occasional to frequent |

| Ponding duration | Long (7 to 30 days) |

| Ponding frequency | None to occasional |

| Elevation | 0 – 6 m |

| Slope | 0 – 1% |

| Ponding depth | 38 cm |

| Water table depth | 0 – 69 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate is predominately maritime, controlled by the warm and very moist air masses from the Gulf of Mexico. The climate along the upper coast of the barrier islands is subtropical subhumid and the climate on the lower coast of Padre Island is subtropical semiarid (due to high evaporation rates that exceed precipitation). Almost constant sea breezes moderate the summer heat along the coast. Winters are generally warm and are occasionally interrupted by incursions of cool air from the north. Spring is mild and damaging wind and rain may occur during spring and summer months. Tropical cyclones or hurricanes can occur with wind speeds of greater than 74 mph and have the potential to cause flooding from torrential rainstorms. Despite the threat of tropical storms, the storms are rare. Throughout the year, the prevailing winds are from the southeast to south-southeast.

The average annual precipitation is 45 to 57 inches in the northeastern half of this area, 26 inches at the extreme southern tip of the area, and 30 to 45 inches in the rest of the area. Precipitation is abundant in spring and fall in the southwestern part of the area and is evenly distributed throughout the year in the northeastern part. Rainfall typically occurs as moderate-intensity, tropical storms that produce large amounts of rain during the winter. The average annual temperature is 68 to 74 degrees F. The freeze-free period averages 340 days and ranges from 315 to 365 days.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 262-365 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 864-1,041 mm |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 261-365 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 838-1,118 mm |

| Frost-free period (average) | 324 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 365 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 940 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) PADRE IS NS [USC00416739], Padre Island Ntl Seashor, TX

-

(2) CORPUS CHRISTI NAS [USW00012926], Corpus Christi, TX

-

(3) ROCKPORT ARANSAS CO AP [USW00012972], Rockport, TX

-

(4) PORT O'CONNOR [USC00417186], Port O Connor, TX

-

(5) PALACIOS MUNI AP [USW00012935], Palacios, TX

-

(6) ARANSAS WR [USC00410305], Tivoli, TX

Influencing water features

The sites are poorly drained, permeability is very slow, and runoff is high. They are occasionally to frequently flooded by over-bank flow, and also occasionally to rarely flooded with salt water resulting from tidal surge during tropical storm events. The soils are saturated for long periods and are seldom dry below 12 inches.

Wetland description

This site has hydric soils. Onsite investigation needed to determine local conditions.

Soil features

The site consists of very deep, poorly drained, very slowly permeable soils that formed in clayey alluvial sediments of Holocene age. Soils correlated to this site include: Aransas and Austwell.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

–

igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rock

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Clay (2) Silty clay |

| Family particle size |

(1) Fine |

| Drainage class | Poorly drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow |

| Soil depth | 203 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-152.4cm) |

5.08 – 12.7 cm |

| Electrical conductivity (0-152.4cm) |

6 – 20 mmhos/cm |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-152.4cm) |

7.4 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (0-152.4cm) |

2 – 5% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (0-152.4cm) |

0% |

Ecological dynamics

The Texas coastline is composed of barrier islands, peninsulas, bays, estuaries, and natural or man-made passes. These mobile environments are constantly reshaped by the process of erosion and accretion. Hurricane activity can significantly change the environment. The Padre Island region is subdivided into habitats based on landform and vegetation. The Salty Bottomland ecological site lies the sides of rivers headed towards the Gulf of Mexico.

The plant communities are dynamic, and composition may vary dramatically with variations in annual rainfall, grazing, and fire. This landscape is floodplain that is impacted by flooding events. Because of southern proximity and nearness to the Gulf of Mexico, extreme climatic variations ranging from extended drought to hurricanes are possible. Bare ground may predominate during droughts or following hurricanes while a midgrass prairie may predominate under proper management and non-droughty periods.

This site has historically been a wet grassed bottom. The community fluctuates depending on grazing history and length of inundation by high salinity water. As rain occurs inland, fresh water is pumped through the rivers. But, during drought times, salt water comes up from the ocean. Changes in the reference community occur when continued overuse by livestock results in a mores midgrasses, then a shift to forbs, and at its most heavily changed, a mudflat. Restoration efforts require time and deferment to regain lost vigor.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Prolonged inundation coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| R2A | - | Natural regeneration over time |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

Community 1.1

Wet Mid/Tallgrass Bottom

The reference plant community is a mixture of mid and tallgrasses that makeup 85 to 90 percent of the biomass. Dominant grasses that make up 75 to 80 percent of the biomass are gulf cordgrass and marshhay cordgrass. Other species include mixes of smooth cordgrass, seashore saltgrass, shoregrass, seashore paspalum, seashore dropseed, common reed, and bulrushes. Forbs include glasswort, sea-Iavender, buckwheat, and sumpweed. Woody plants are generally sparse in this community but would include sea-oxeye and wolfberry.

Figure 8. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 4035 | 6053 | 9079 |

| Shrub/Vine | 224 | 336 | 504 |

| Forb | 224 | 336 | 504 |

| Total | 4483 | 6725 | 10087 |

Community 1.2

Wet Midgrass/Forb Bottom

This community is similar to the reference community but there is a decrease in marshhay cordgrass and an increase in gulf cordgrass. In addition, smooth cordgrass, seashore saltgrass, common reed, seashore dropseed, and seashore paspalum decrease in abundance. Shoregrass, sea ox-eye, devil-weed, and coffeebean increase in abundance. This shift in composition is driven by heavy grazing, but may also occur during extended periods of high salinity.

Community 1.3

Wet Forb Bottom

With continued heavy grazing and/or severe, persistent high salinities, the grass cover of this community begins to open, and the amount of bare ground increases along with an increase of forbs. Devil-weed, sea ox-eye, rag sumpweed, seacoast sumpweed, bulrushes, eastern baccharis (Baccharis halimifolia), and assorted sedges and rushes become dominant. When dominated by these species it may be very difficult to return to the composition of the previous communities by grazing management alone. Pest management, brush management, and prescribed grazing in combination may be necessary to improve the condition.

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Heavy continuous grazing or prolonged high salinity will shift the reference community to Community 1.2.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Prescribed grazing, specifically deferment, and lower salinity conditions will transition the Community 1.2 back to reference conditions.

Pathway 1.2B

Community 1.2 to 1.3

Continued heavy grazing or continued prolonged high salinity will shift the reference community to Community 1.3.

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.2

Prescribed grazing, specifically deferment, and lower salinity conditions will possibly transition the Community 1.3 back to Community 1.2. Once the site reaches the Wet Forb Bottom (1.3), it becomes more difficult to restore reference conditions.

State 2

Mudflat

Vegetation severely reduced or absent.

Community 2.1

Mudflat

At the extreme, the site would not have any plants present. In most cases, depending upon the duration of the flooding, drying or salinity conditions, some remnant plants would exist. Most of the preferred species that occur tend to reproduce by vegetative means and the rate of recovery to a vegetated state will be controlled by the density and vigor of these remnant plants. This is coupled with the size of the mudflat and how that would influence spread by vegetative means from surrounding areas. Recovery may be very slow. Reseeding is not generally feasible due to lack of a seed source and difficulty of seedling establishment. Planting of vegetative materials can assist in accelerating the recovery process but may not be feasible over large areas. Generally, rest from further disturbance may be the only reasonable approach to recovery but this may require several years.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Further continued heavy grazing and extremely long inundation with saltwater will transition the reference state to a Mudflat State (2).

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Restoration back to the Wet Bottom State (1) generally requires rest from further disturbance and may be the only reasonable approach to recovery, but this may take several years.

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | 0–2 | |||||

| saltmeadow cordgrass | SPPA | Spartina patens | 0–1 | – | ||

| gulf cordgrass | SPSP | Spartina spartinae | 0–1 | – | ||

| 2 | 0–17 | |||||

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | 0–1 | – | ||

| flatsedge | CYPER | Cyperus | 0–1 | – | ||

| saltgrass | DISP | Distichlis spicata | 0–1 | – | ||

| shoregrass | MOLI | Monanthochloe littoralis | 0–1 | – | ||

| longtom | PADE24 | Paspalum denticulatum | 0–1 | – | ||

| seashore paspalum | PAVA | Paspalum vaginatum | 0–1 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVIV | Panicum virgatum var. virgatum | 0–1 | – | ||

| Southern Sierra phacelia | PHAU | Phacelia austromontana | 0–1 | – | ||

| chaffseed | SCAM | Schwalbea americana | 0–1 | – | ||

| marsh bristlegrass | SEPA10 | Setaria parviflora | 0–1 | – | ||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 0–1 | – | ||

| smooth cordgrass | SPAL | Spartina alterniflora | 0–1 | – | ||

| hairy sandspurry | SPVI | Spergularia villosa | 0–1 | – | ||

| eastern gamagrass | TRDA3 | Tripsacum dactyloides | 0–1 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | 0–12 | |||||

| alligatorweed | ALPH | Alternanthera philoxeroides | 0–1 | – | ||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 0–1 | – | ||

| rush milkweed | ASSU | Asclepias subulata | 0–1 | – | ||

| bushy seaside tansy | BOFR | Borrichia frutescens | 0–1 | – | ||

| narrowleaf marsh elder | IVAN | Iva angustifolia | 0–1 | – | ||

| Jesuit's bark | IVFR | Iva frutescens | 0–1 | – | ||

| petiteplant | LESP | Lepuropetalon spathulatum | 0–1 | – | ||

| California desert-thorn | LYCA | Lycium californicum | 0–1 | – | ||

| Virginia glasswort | SADE10 | Salicornia depressa | 0–1 | – | ||

| slender seapurslane | SEMA3 | Sesuvium maritimum | 0–1 | – | ||

| annual seepweed | SULI | Suaeda linearis | 0–1 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 4 | 0–3 | |||||

| eastern baccharis | BAHA | Baccharis halimifolia | 0–1 | – | ||

| bigpod sesbania | SEHE8 | Sesbania herbacea | 0–1 | – | ||

| French tamarisk | TAGA | Tamarix gallica | 0–1 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

The animal communities of the Coastal Prairie communities are influenced by fresh and salt water inundations. Cattle and many species of wildlife make extensive use of the site. White-tailed deer may be found scattered across the prairie and are found in heavier concentrations where woody cover exists. Feral hogs are present and at times become abundant. Coyotes are abundant and fill the mammalian predator niche. Rodent populations rise during drier periods and fall during periods of inundation. Alligators are locally abundant and make frequent use of the marshes depending on salt concentrations in the marshes.

The region is a major flyway for waterfowl and migrating birds. Hundreds of thousands of ducks, geese, and sandhill cranes abound during winter. Whooping cranes are an important endangered species that occur in the area, especially near Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. Northern harriers are common predatory birds seen patrolling marshes. Curlews, plovers, sandpipers, and willets are shorebirds that make use of the tidal areas. Seagulls and terns are plentiful throughout the year trolling the shores as well. Further inland, rails, gallinules, and moorhens make use of the brackish marshes.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented was derived from the Range Site Description, NRCS clipping data, literature, field observations, and personal contacts with range-trained personnel.

Other references

Archer, S. 1994. Woody plant encroachment into southwestern grasslands and savannas: rates, patterns and proximate causes. Ecological implications of livestock herbivory in the West, 13-68.

Archer, S. and F. E. Smeins. 1991. Ecosystem-level processes. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heischmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Bailey, V. 1905. North American Fauna No. 25: Biological Survey of Texas. United States Department of Agriculture Biological Survey. Government Printing Office, Washington D. C.

Beasom, S. L, G. Proudfoot, and J. Mays. 1994. Characteristics of a live oak-dominated area on the eastern South Texas Sand Plain. In the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute Annual Report, 1-2.

Bestelmeyer, B. T., J. R. Brown, K. M. Havstad, R. Alexander, G. Chavez, and J. E. Herrick. 2003. Development and use of state-and-transition models for rangelands. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):114-126.

Briske, B. B, B. T. Bestelmeyer, T. K. Stringham, and P. L. Shaver. 2008. Recommendations for development of resilience-based State-and-Transition Models. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 61:359-367.

Brown, J. R. and S. Archer. 1999. Shrub invasion of grassland: recruitment is continuous and not regulated by herbaceous biomass or density. Ecology, 80(7):2385-2396.

Butzler, R. E. 2006. The Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Lycium carolinianum Walt. M. S. Thesis. Texas A&M, College Station, TX.

Chabreck, R. H. 1972. Vegetation, water and soil characteristics of the Louisiana coastal region. Louisiana State University Agriculture Experiment Station Bulletin, 664.

Davis, W. B. 1974. The Mammals of Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Bulletin, 41.

Drawe, D. L., A. D. Chamrad, and T. W. Box. 1978. Plant communities of the Welder Wildlife Refuge. The Welder Wildlife Refuge, Sinton, TX.

Drawe, D. L., K. R. Kattner, W. H. McFarland, and D. D. Neher. 1981. Vegetation and soil properties of five habitat types on north Padre Island. Texas Journal of Science, 33:145-157.

Everitt, J. H., D. L. Drawe, and R. I. Leonard. 2002. Trees, Shrubs, and Cacti of South Texas. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, TX.

Foster, J. H. 1917. Pre-settlement fire frequency regions of the United States: A first approximation. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 20.

Frost, C. C. 1995. Presettlement fire regimes in southeastern marshes, peatlands, and swamps. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 19:39-60.

Fulbright, T. E., D. D. Diamond, J. Rappole, and J. Norwine. 1990. The Coastal Sand Plain of Southern Texas. Rangelands, 12:337-340.

Fulbright, T. E., J. A. Ortega-Santos, A. Lozano-Cavazos, and L. E. Ramirez-Yanez. 2006. Establishing vegetation on migrating inland sand dunes in Texas. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 59:549-556.

Gosselink, J.D., C.L. Cordes, and J.W. Parsons. 1979. An. Ecological characterization study of the Chenier Plain Coastal Ecosystem of Louisiana and Texas. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Biological Services, Washington, D.C.

Gould, F. W. 1975. The Grasses of Texas. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Gould, F. W. and T. W. Box. 1965. Grasses of the Texas Coastal Bend. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Grace, J. B., L. K. Allain, H. Q. Baldwin, A. G. Billock, W. R. Eddleman, A. M. Given, C. W. Jeske, and R. Moss. 2005. Effects of prescribed fire in the coastal prairies of Texas. USGS Open File Report, 2005-1287.

Hamilton, W. and D. Ueckert. 2005. Rangeland woody plant control: Past, present, and future. Brush management: Past, present, and future, 3-16.

Harcombe, P. A. and J. E. Neaville. 1997. Vegetation types of Chambers County, Texas. The Texas Journal of Science, 29:209-234.

Hatch, S. L., J. L. Schuster, and D. L. Drawe. 1999. Grasses of the Texas Gulf Prairies and Marshes. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Johnson, M. C. 1963. Past and present grasslands of southern Texas and northeastern Mexico. Ecology 44(3):456-466.

Lehman, V. W. 1965. Fire in the range of Attwater’s prairie chicken. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, 4:127-143.

Mann, C. 2004. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. Vintage Books, New York City, NY.

Mapston, M. E. 2007. Feral Hogs in Texas. Texas Agrilife Extension Bulletin, B-6149

McAtee, J. W., C. J. Scifres, D. L. and Drawe. 1979. Digestible energy and protein content of gulf cordgrass following burning or shredding. Journal of Range Management, 376-378.

McGowen, J. H., L. F. Brown, T. J. Evans, W. L. Fisher, and C. G. Groat. 1976. Environmental geologic atlas of the Texas Coastal Zone-Bay City-Freeport area. The University of Texas at Austin, Bureau of Economic Geology, Austin, TX.

Miller, D. L., F. E Smeins, and J. W. Webb. 1998. Response of a Texas Distichlis spicata coastal marsh following Lesser Snow Goose herbivory. Aquatic Botany, 61:301-307.

Miller, D. L., F. E. Smeins, and J. W. Webb. 1996. Mid-Texas coastal marsh change (1939-1991) as influenced by Lesser Snow Goose herbivory. Journal of Coastal Research, 12:462-476.

Miller, D. L., F. E. Smeins, J. W. Webb, and M. T. Longnecker. 1997. Regeneration of Scirpus americanus in a Texas coastal marsh following Lesser Snow Goose herbivory. Wetlands, 17:31-42.

Oefinger, R. D. and C. J. Scifres. 1977. Gulf cordgrass production, utilization, and nutritional value following burning. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, B-1176.

Palmer, G. R., T. E. Fulbright, and G. McBryde. 1995. Inland sand dune reclamation on the Coastal Sand Plain of Southern Texas. Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute Annual Report, 1994-1995.

Prichard, D. 1998. Riparian area management: A user guide to assessing proper functioning condition and the supporting science for lotic areas. Bureau of Land Management, Denver, CO.

Rappole, J. H. and G. W. Blacklock. 1985. Birds of the Texas Coastal Bend: Abundance and distribution. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Scifres, C. J. and W. T. Hamilton. 1993. Prescribed burning for brushland management: The South Texas example. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX.

Scifres, C. J., J. W. McAtee, and D. L. Drawe 1980. Botanical, edaphic, and water relationships of gulf cordgrass (Spartina spartinae [Trin.] Hitchc.) and associated communities. The Southwestern Naturalist, 25(3):397-409.

Shiflet, T. N. 1963. Major ecological factors controlling plant communities in Louisiana marshes. Journal of Range Management, 16:231-235.

Singleton, J. R. 1951. Production and utilization of waterfowl food plants on the east Texas gulf coast. Journal of Wildlife Management, 15:46-56.

Smeins, F. E., D. D. Diamond, and W. Hanselka. 1991. Coastal prairie, 269-290. Ecosystems of the World: Natural Grasslands. Edited by R. T. Coupland. Elsevier Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Smeins, F. E., S. Fuhlendorf, and C. Taylor, Jr. 1997. Environmental and land use changes: A long term perspective. Juniper Symposium, 1-21.

Snyder, R. A. and C. L. Boss. 2002. Recovery and stability in barrier island plant communities. Journal of Coastal Research, 18:530-536.

Stoddart, L. A., A. D. Smith, and T. W. Box. 1975. Range management. McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, NY.

Stringham, T. K., W. C. Krueger, and P. L. Shaver. 2001. State and transition modeling: An ecological process approach. Journal of Range Management, 56(2):106-113.

Thornthwaite, C. W. 1948. An approach towards a rational classification of climate. Geographical Review, 38: 55-94.

Thurow, T. L. 1991. Hydrology and erosion. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective. Edited by R.K. Heitschmidt and J.W. Stuth. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Urbatsch, L. 2000. Chinese tallow tree Triadica sebifera (L.) Small. USDA-NRCS, National Plant Center, Baton Rouge, LA.

Van’t Hul, J. T., R. S. Lutz, and N. E. Mathews. 1997. Impact of prescribed burning on vegetation and bird abundance on Matagorda Island, Texas. Journal of Range Management, 50:346-360.

Vines, R. A. 1977. Trees of Eastern Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Vines, R. A. 1984. Trees of Central Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Wade, D. D., B. L. Brock, P. H. Brose, J. B. Grace, G. A. Hoch, and W. A. Patterson III. 2000. Fire in Eastern ecosystems. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora. Edited by. J. K. Brown and J. Kaplers. United States Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden, UT.

Warren, W. S. 1998. The La Salle Expedition to Texas: The journal of Henry Joutel, 1684-1687. Edited by W. C. Foster. Texas State Historical Association, Austin, TX.

Weaver, J. E. and F. E. Clements. 1938. Plant ecology. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Williams, A. M., R. A. Feagin, W.K. Smith, and N. L. Jackson. 2009. Ecosystem impacts of Hurricane Ike on Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula: Perspectives of the coastal barrier island network (CBIN). Shore and Beach, 7(2):1-5.

Williams, L. R. and G. N Cameron. 1985. Effects of removal of pocket gophers on a Texas coastal prairie. The American Midland Naturalist Journal, 115:216-224.

Wright, H.A. and A.W. Bailey. 1982. Fire Ecology: United States and Southern Canada. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Contributors

Fred E. Smeins, Professor, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX

Acknowledgments

Site Development and Testing Plan:

Future work, as described in a Project Plan, to validate the information in this Provisional Ecological Site Description is needed. This will include field activities to collect low, medium and high-intensity sampling, soil correlations, and analysis of that data. Annual field reviews should be done by soil scientists and vegetation specialists. A final field review, peer review, quality control, and quality assurance reviews of the ESD will be needed to produce the final document. Annual reviews of the Project Plan are to be conducted by the Ecological Site Technical Team.

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 03/03/2026 |

| Approved by | Bryan Christensen |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

Ecosystem states

| T1A | - | Prolonged inundation coupled with excessive grazing pressure |

|---|---|---|

| R2A | - | Natural regeneration over time |