Ecological dynamics

This site describes woodlands surrounding gallery forests along and near rivers such as the Nushagak River. It is on plain talfs and rises. Local site factors including soil characteristics and a fire regime shape three communities in the reference state. The reference plant community is a mixed birch and white spruce forest.

Fire is the major disturbance on this site. Fire affects myriad biotic and abiotic characteristics, including soil factors (Liljedahl et al., 2007; Hinzman et al., 2006), and the richness and diversity of vegetation (Racine et al., 1987; Boucher, 2003). Fires in cooler and moister habitats tend to result in low-severity burns; those in warmer and drier habitats generally produce high-severity burns. Low-severity burns are typical for this ecological site. The relatively robust population of lichens and mosses in the early fire community phase suggests that while the overstory canopy may be removed, the understory may experience a patchy burn that avoids burning all areas. Fire cycles tend to be longer in Western and Southwest Alaska than in the Interior (Viereck and Schandelmeier, 1980; Trigg 1971). The mean age of white spruce in the reference plant community is 80 to 100 years, suggesting a current fire cycle of about a century.

Windthrow occurs in the reference plant community. It does not result in a unique community. However, it may keep the forest canopy open and promote plant diversity in the understory. Willows are browsed by moose. Caribou browse willow and lichens. This does not appear to affect the ecological processes of the site.

There are two alternate states on this site. The first state is the result of selective thinning and harvesting of trees. This occurs most frequently around villages and towns. The second state results from complete removal of vegetation, often by bulldozer or plow. Bulldozing not only removes vegetation but alters the soil and seedbank. This state is also most frequently found around inhabited areas.

The information in this Ecological Dynamics section, including the state-and-transition model (STM), was developed based on current field data, professional experience, and a review of the scientific literature. As a result, all possible scenarios or plant species may not be included. Key indicator plant species, disturbances, and ecological processes are described to inform land management decisions.

State 1

Reference State

Figure 7. Aerial view of the mixed forest reference plant community in foreground.

The reference state supports three community phases, which are distinguished by the developed structure and dominance of the vegetation and by their ecological function and stability. The reference community phase is an open mixed forest (Viereck et al., 1992). The presence of each community is dictated temporally by a fire disturbance regime.

This report provides baseline inventory data on the vegetation. Future data collection is needed to provide further information about existing plant communities and the disturbance regimes that result in transitions from one community to another. Common and scientific names are from the USDA PLANTS database. Community phases are characterized by the Alaska Vegetation Classification System (Viereck et al., 1992).

Community 1.1

White spruce-paper birch/lingonberry-black crowberry

Figure 8. Typical area of community 1.1.

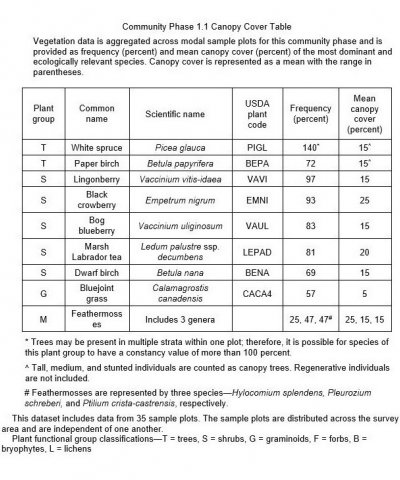

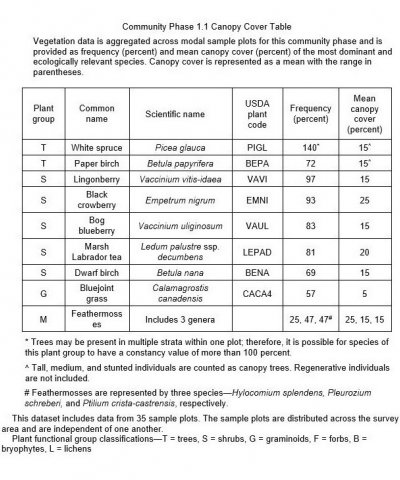

Figure 9. Frequency and canopy cover of plants in community 1.1.

The reference plant community is characterized by an open mixed forest that has an understory of dominantly shrubs and mosses. Trees are in all four height strata (regenerative trees less than 15 feet high to tall trees more than 40 feet high). Typically, this community consists of an overstory of white spruce (Picea glauca) and paper birch (Betula papyrifera) and an understory of low and dwarf shrubs such as lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), black crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), bog blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), dwarf birch (Betula nana), and marsh Labrador tea (Ledum palustre ssp. decumbens) and feathermosses. Other species may include Kenai birch (Betula papyrifera var. kenaica), dwarf birch (Betula nana), bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis), sedges (Carex spp.), fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), and horsetails (Equisetum spp.). Lichens, particularly reindeer lichens (Cladina spp.) and cup lichens (Cladonia spp.), and mosses, mainly feathermosses, are common in the ground cover. Other ground cover typically includes herbaceous litter and woody litter.

Dominant plant species

-

white spruce (Picea glauca), tree

-

paper birch (Betula papyrifera), tree

-

lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), shrub

-

black crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), shrub

-

bog blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), shrub

-

marsh Labrador tea (Ledum palustre ssp. decumbens), shrub

-

dwarf birch (Betula nana), shrub

-

bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis), grass

-

splendid feather moss (Hylocomium splendens), other herbaceous

-

Schreber's big red stem moss (Pleurozium schreberi), other herbaceous

-

knights plume moss (Ptilium crista-castrensis), other herbaceous

Community 1.2

Paper birch/lingonberry-black crowberry/bluejoint

Figure 10. Typical area of community 1.2.

Figure 11. Frequency and canopy cover of plants in community 1.2.

The late fire community phase is characterized by an open broadleaf forest. A low density of white spruce, Kenai birch, or quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) creates an open forest in some areas. Typically, this community has an overstory of paper birch and an understory of lingonberry, black crowberry, marsh Labrador tea, bog blueberry, and bluejoint. The understory is dense in some areas. Other species extant in this community include spirea (Spiraea stevenii), dwarf birch, willows (Salix spp.), sedges (Carex spp.), fireweed, field horsetail (Equisetum arvense), and woodland horsetail (Equisetum sylvaticum). Lichens and mosses are common in the ground cover. Other ground cover commonly includes herbaceous litter and woody litter. Some areas are bare soil.

Dominant plant species

-

paper birch (Betula papyrifera), tree

-

lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), shrub

-

black crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), shrub

-

marsh Labrador tea (Ledum palustre ssp. decumbens), shrub

-

bog blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), shrub

-

bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis), grass

-

fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), other herbaceous

-

splendid feather moss (Hylocomium splendens), other herbaceous

-

Schreber's big red stem moss (Pleurozium schreberi), other herbaceous

-

knights plume moss (Ptilium crista-castrensis), other herbaceous

Community 1.3

Kenai birch-quaking aspen/marsh Labrador tea-lingonberry/bluejoint

Figure 12. Typical area of community 1.3.

Figure 13. Frequency and canopy cover of plants in community 1.3.

The early fire community phase is characterized by an open broadleaf forest that has an understory of shrubs. Typically, this community consists of an overstory of quaking aspen and Kenai birch and an understory of marsh Labrador tea, lingonberry, black crowberry, and bog blueberry. Other species extant in this community include bluejoint, Bigelow’s sedge (Carex bigelowii), horsetails, and willows. Lichens and mosses are common in the ground cover. Other ground cover includes herbaceous litter and woody litter. Some areas are bare soil.

Dominant plant species

-

Kenai birch (Betula papyrifera var. kenaica), tree

-

quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), tree

-

marsh Labrador tea (Ledum palustre ssp. decumbens), shrub

-

black crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), shrub

-

lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), shrub

-

bog blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), shrub

-

bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis), grass

-

fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), other herbaceous

-

Schreber's big red stem moss (Pleurozium schreberi), other herbaceous

-

splendid feather moss (Hylocomium splendens), other herbaceous

-

knights plume moss (Ptilium crista-castrensis), other herbaceous

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.3

White spruce-paper birch/lingonberry-black crowberry

Kenai birch-quaking aspen/marsh Labrador tea-lingonberry/bluejoint

Fire.

A low-intensity fire may damage trees and taller shrubs, but pockets of low vegetation may remain. The decreased competition for light and space allows fast-growing tree species to colonize (such as quaking aspen [Populus tremuloides], which is highly competitive in burned sites [DeByle et al., 1987]) and allows for propagation of the pockets of low and dwarf shrubs that remain. Based on the soil data and age of in situ trees, a low-intensity fire is hypothesized to occur once every 100 years.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Paper birch/lingonberry-black crowberry/bluejoint

White spruce-paper birch/lingonberry-black crowberry

Time and growth without disruptive fire.

Over time after a fire, white spruce (Picea glauca) will colonize the deciduous woodland and become the dominant tree species. As the coniferous cover increases and the deciduous cover decreases, the total canopy cover generally increases only slightly and the established understory remains relatively stable. The time required for this transition is unknown. It likely depends on various factors, including the distance to a seed source and growth rate of trees.

Pathway 1.2B

Community 1.2 to 1.3

Paper birch/lingonberry-black crowberry/bluejoint

Kenai birch-quaking aspen/marsh Labrador tea-lingonberry/bluejoint

Fire.

A low-intensity, fast-burning fire may remove trees and taller shrubs, but pockets of low vegetation may remain. The decreased competition for light and space allows fast-growing tree species to colonize (such as quaking aspen [Populus tremuloides], which is highly competitive in burned areas [DeByle et al., 1987]) and allows for propagation of the pockets of low and dwarf shrubs that remain. It currently is unknown how often this community is subject to a fire.

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.2

Kenai birch-quaking aspen/marsh Labrador tea-lingonberry/bluejoint

Paper birch/lingonberry-black crowberry/bluejoint

Natural succession: Time and growth without disruptive fire.

As burned areas recover, other deciduous trees may colonize and eventually outshade quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). The total canopy cover does not appear to fluctuate greatly, which allows the established understory to remain relatively stable. The richness of species may increase as new niches are established. The period needed for this transition is unknown. It likely depends on a variety of factors, including the distance to a seed source and growth rate of trees.

State 2

Tree Thinning/Harvesting State

This alternate state results from the thinning or harvesting of trees. This disturbance commonly occurs in or around villages and camps and generally includes collection of woody material for use in construction and as firewood. Removal of trees commonly opens the overstory and reduces competition for light in the understory. This may alter the abundance of species, but the richness of the community typically remains.

Field observations suggest that these areas commonly are reharvested; thus, the alternate state is maintained perpetually. No documentation exists for a transition of this alternate state back to the reference state; however, it is hypothesized that the cessation of thinning and harvesting may allow the community to return to the reference state eventually.

Community 2.1

Alaska paper birch-white spruce/black crowberry-lingonberry

Figure 14. Typical area of community 2.1.

Figure 15. Frequency and canopy cover of plants in community 2.1.

The late community of the alternate state is characterized by an open mixed forest that has an understory of dense, low and dwarf shrubs. Typically, this community supports Alaska paper birch (Betula neoalaskana) and white spruce in the overstory and black crowberry, lingonberry, and bog blueberry in the understory and open areas. Other species may include bluejoint, marsh Labrador tea, spirea, fireweed, and woodland horsetail. Mosses are a major component in the ground cover, and lichens are a minor component. Other ground cover commonly includes herbaceous litter and woody litter.

Community 2.2

Black crowberry-lingonberry/polytrichum moss

Figure 16. Typical area of community 2.2.

Figure 17. Frequency and canopy cover of plants in community 2.2.

The early community phase of this alternate state occurs immediately following anthropogenic disturbance. It is characterized as a closed low scrubland (Viereck et al., 1992) that consists of low and dwarf shrubs. Typically, the community consists of black crowberry, lingonberry, marsh Labrador tea, and bog blueberry. Other extant species include Barclay’s willow (Salix barclayi), bluejoint, Altai fescue (Festuca altaica), and fireweed. Individual trees, including white spruce, Alaska paper birch, quaking aspen, and paper birch, may be present. A mat of mosses, typically polytrichum mosses (Polytrichum spp.) and one or more feathermosses, is common. The ground cover may also include lichens, herbaceous litter, and woody litter. Some areas are bare soil.

Pathway 2.2B

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Black crowberry-lingonberry/polytrichum moss

Alaska paper birch-white spruce/black crowberry-lingonberry

Time and growth without harvesting.

As harvesting activities slow or cease, trees may colonize and form a canopy. The period needed for this transition is unknown. It likely depends on the distance to a seed source and cessation of anthropogenic activities.

State 3

Cultural/Agronomic State

This alternate state results from the anthropogenic clearing of all trees and shrubs from a prescribed area. This commonly involves disturbances, including compaction or removal of the soil. This state commonly is within the boundaries of villages, and it may include areas cleared for lawns or agricultural uses.

Clearing of the vegetation in any of the reference state community phases will result in a transition to community phase 3.1. Areas of this alternate state commonly are mowed to prevent colonization of shrubs and keep graminoids and forbs below a maximum height. Taller shrubs and trees may colonize if these areas are abandoned, but this has not been observed in situ.

Community 3.1

Bluejoint/fireweed

Figure 18. Typical area of community 3.1.

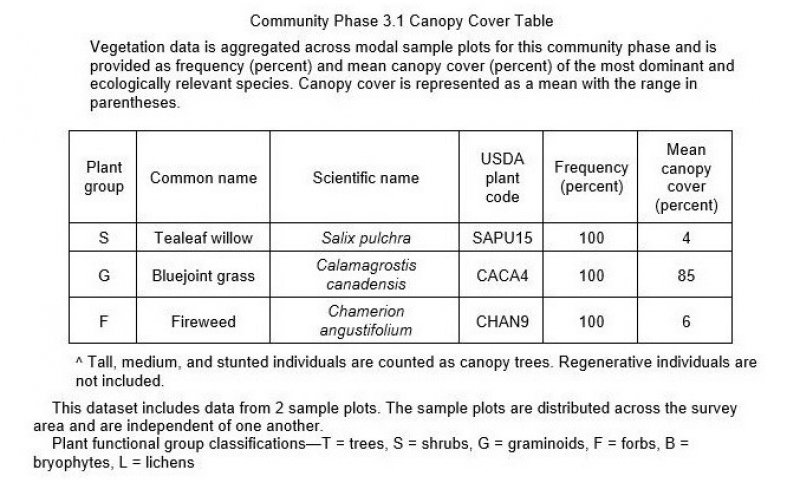

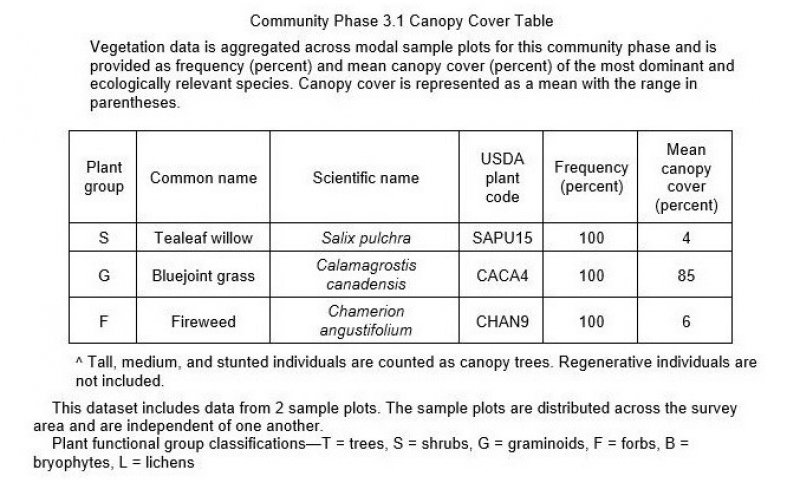

Figure 19. Frequency and canopy cover of plants in community 3.1.

This alternate state community phase is characterized as a mesic graminoid herbaceous meadow (Viereck et al., 1992). Typically, this community is grassland that consists of bluejoint and sporadic fireweed, tealeaf willow (Salix pulchra), and paper birch. Other species may include seacoast angelica (Angelica lucida), arctic starflower (Trientalis europaea), and horsetails. Mosses generally are a minor component in the ground cover, and lichens are rare. Other ground cover commonly includes herbaceous litter and woody litter.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Anthropogenic thinning and harvesting of trees near and in villages and towns results in this transition. The threshold between the plant community remaining in the reference phase and transitioning to the alternate state depends solely on the extent of thinning and harvesting of trees.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Clearing of all vegetation from the reference state will result in community phase 3.1. Bulldozed soils are compacted or removed during removal of the naturally occurring vegetation. This anthropogenic disturbance is drastic. No threshold allows the plant community to remain in the reference state.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

No apparent active restoration activity will transition alternate state 2 to the reference state. Although situ data are not available, it is hypothesized that state 2 will passively return to the reference state if thinning and harvesting activities are ceased. The period required depends on various anthropogenic and natural factors, including the extent of the original thinning or harvesting, cessation of anthropogenic disturbance, and lack of a natural fire disturbance.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 1

The cultural/agronomic alternate state may be restored to the reference state by ceasing mowing and planting trees and understory species. A passive transition of this alternate state to the reference state has not been observed in situ. If anthropogenic activity is ceased, the state to which these mowed areas may transition naturally is unknown. Thus, it is impossible to hypothesize whether the state can or will transition to the reference state naturally.