Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F030XC292NV

LIMESTONE SLOPES

Last updated: 4/26/2024

Accessed: 03/11/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Ecological site concept

This forest site occurs on mountain backslopes. Slopes range from 15 to 75 percent, but are typically 30 to 50 percent. Elevations are 7000 to 8800 feet. Soils associated with this forest site are moderately deep, well drained and formed in colluvium and residuum from limestone and dolomitic limestone. The soils of this site are loamy-skeletal with 50 to 80 percent rock fragments by volume, mainly gravels and cobbles.

Associated sites

| F030XC293NV |

QUARTZITE SLOPES PIPOS/ARTRV/POFE |

|---|

Similar sites

| F030XC293NV |

QUARTZITE SLOPES PIPOS/ARTRV/POFE [More productive, ARTRV dominant shrub] |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Pinus ponderosa ssp. scopulorum |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Artemisia nova |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Poa fendleriana |

Physiographic features

This forest site occurs on mountain backslopes. Slopes range from 15 to 75 percent, but are typically 30 to 50 percent. Elevations are 7000 to 8800 feet. Soils associated with this forest site are moderately deep, well drained and formed in colluvium and residuum from limestone and dolomitic limestone. The soils of this site are loamy-skeletal with 50 to 80 percent rock fragments by volume, mainly gravels and cobbles.

This site is part of group concept F030XC287NV.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Mountain slope

|

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 2,134 – 2,682 m |

| Slope | 15 – 75% |

Climatic features

The climate is semi-arid with warm, dry summers and cold, moist winters. Precipitation is greatest in the winter with a lesser secondary peak in the summer, typical of the Mojave Desert transitional to the Great Basin. Average annual precipitation is approximately 13 to 15 inches. Mean annual air temperature is 54 F. The average frost free period is 50 to 150 days.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 150 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | |

| Precipitation total (average) | 381 mm |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Influencing water features

There are no influencing water features associated with this ecological site.

Soil features

Soils associated with this forest site are moderately deep, well drained and formed in colluvium and residuum from limestone and dolomitic limestone. The soils of this site are loamy-skeletal with 50 to 80 percent rock fragments by volume, mainly gravels and cobbles. Runoff is very high, and saturated hydraulic conductivity is moderately high. Soils are characterized by a mollic epipedon from 0 to 30 inches, a calcic horizon from 7 to 35 inches, lithic contact beginning at 35 inches and aridic moisture regime bordering on ustic. The official soil series correlated to this ecological site includes Sawmillcan, a loamy-skeletal, carbonatic, mesic Pachic Calciustoll.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Colluvium

–

limestone

(2) Residuum – dolomite |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Very gravelly loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow |

| Soil depth | 51 – 99 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 45 – 55% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 8 – 12% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

2.54 – 7.62 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

25 – 45% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 4 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 5 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

7.6 – 8 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

35 – 65% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

5 – 25% |

Ecological dynamics

The plant communities of this site are dynamic in response to changes in disturbance regimes and weather patterns. Disturbances, such as fire, play an important role in all forest ecosystems. Important processes that are regulated by fire include regeneration and reproduction, seedbed preparation, competition reduction and thinning to maintain stand health (Spurr and Barnes 1964). Rocky Mountain ponderosa pine is found throughout the West and grows on discontinuous mountains, plateaus, and canyons. A possible explanation for its limited and spotty distribution is correlated to the distribution of sites that receive summer rainfall (Oliver and Ryker 1992). Ponderosa pine seedlings are able to grow taproots that extend greater than 20 inches within a few months of germination (Oliver and Ryker 1992). This ability is essential for survival in desert ecosystems. Rocky mountain ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa var. scopulorum) differs from variety ponderosa with its shorter needles, fewer needles per fascicle, germination rate and root growth capacity (Krugman and Jenkinson 2008). Investigation to the vast genetic diversity of P. ponderosa suggests there are five major geographic races, including two distinct races in variety scopulorum. Northern sources of variety scopulorum are characterized by relatively good growth and frost resistance. The southern sources, which occur in Nevada, are slower growing but also frost resistant (Krugman and Jenkinson 2008). Rocky Mountain ponderosa pine has migrated into the Great Basin following the ice ages by way of the Southern Rocky Mountains. Rocky Mountain ponderosa pine never attains the size of the typical variety (P. ponderosa var. ponderosa).

Soils provide physical support, moisture and nutrients to the forest community. Trees have reciprocating effects on the soil. Since they tend to exist on site for extended periods of time, their roots typically extend deep into the subsoil and even into fractured bedrock influencing the rate of soil development. Considerable amounts of organic material are returned to the soil in the form of fallen litter and decaying roots. Increased organic matter on the soil surface, or litter layer, helps to keep moisture conditions more uniform. Insulation provided by the tree canopy and litter layer also reduces the temperature fluctuation from day to night (Fisher and Binkley 2002). Seedlings of ponderosa pine grow best with warm days and warm nights. Root growth of ponderosa pine is highly dependent on soil temperature. Low soil temperatures result in low metabolic activity and membrane permeability which limit water and nutrients uptake (Spurr and Barnes 1964).

Biogeochemical cycling in semi-arid forest system is controlled by moisture availability and fire. The role of water is more important in humid systems, which are largely affected by leaching. A review of the literature shows the post fire nitrogen fixation is more important than atmospheric deposition and leaching. Fire affects the nitrogen pool of a forest in 2 ways: 1) due to volatilization during the fire and 2) the influx of nitrogen fixing vegetation following the fire. Increases of nitrogen immediately after fire are attributed to the release of ammonium (NH4+) which takes place at temperatures above 100°C (Johnson et al. 1998). Nitrogen is considered to be a limiting nutrient in this system and the plant community will rapidly respond to inputs of nitrogen. Temporary increases in available nitrogen decrease to pre-burn levels within 5 to 12 years after fire (Johnson et al. 1998). The importance of fire and post fire nitrogen fixation will continue to increase due to changes in fire frequency driven by non-native annuals and the buildup of fuels during decades of fire suppression.

Fire Ecology: Rocky Mountain ponderosa pine is long-lived with individual trees capable of living to 700+ years. Historically, stands were open and comprised of varied age class distribution that evolved with the occurrence of frequent surface fires and the occasional stand-replacing crown fire. Surface fires reoccurred every 5 to 30 years, this maintained open-growth, park-like stands. Stand replacing fires were less common, estimates range from 60 to 160 years (Howard 1993). Mature trees are very resistant to fire. Adaptations include self-pruning branches, thick bark, thick bud scales, tight needle bunches and a deep rooting habit. Seedlings and saplings are susceptible to fire. Periodic ground fires remove heavy litter, duff and unwanted juveniles that accumulate in the forest understory. Fire also prepares the seed bed for regeneration (Howard 1993). Fuel loading in stands of ponderosa pine vary depending on age class, stand structure and understory composition. In the absence of naturally reoccurring wildfire had led to large accumulations of fuels in some ponderosa pine forests and an increase of shade tolerant, less fire resistant, less desirable tree species in the understory. Low severity fires generally kill trees less than 6 inches dbh. Trees infected with dwarf-mistletoe or other diseases are more susceptible to mortality. Rocky Mtn. Juniper and white fir are intolerant of fire. Even low severity fires result in high rates of mortality. Muttongrass easily survives low severity fire, but appears to be harmed by severe fire. The seeds of Ross’ sedge germinate after heat treatment and rhizomes commonly survive fires. Squirreltail can be top killed by fire, but regenerates from the root crown and from seed. Black sagebrush is killed by all fire severities. Reestablishment occurs solely through seed. Wax currant is described as a weak sprouter this is killed by severe fire. Mountain snowberry commonly sprouts from the root crow following fire. Rabbitbrush is top killed by fire. It easily reestablishes by sprouting and by seed. It may increase in cover following wildfire or other disturbance. Purple sage is tolerant of fire and will sprout following burning.

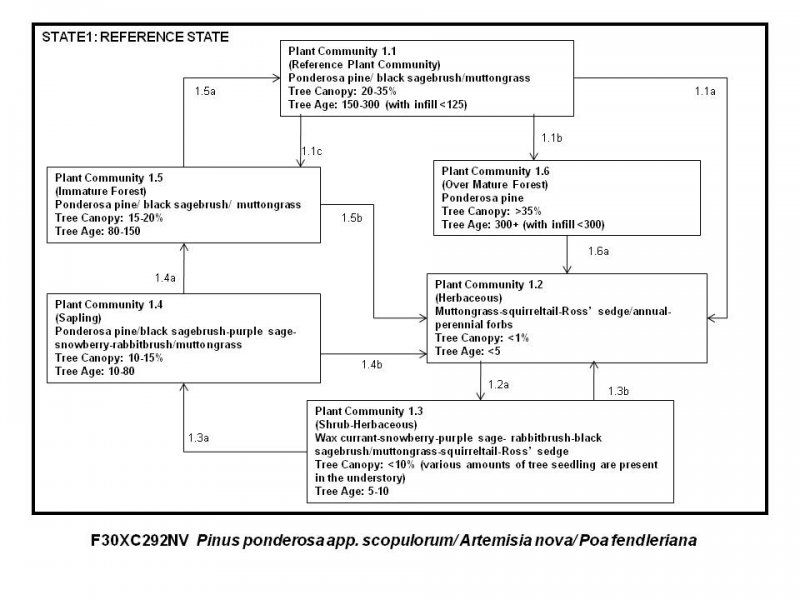

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

State 1 submodel, plant communities

Communities 1, 5 and 6 (additional pathways)

Communities 2, 5 and 6 (additional pathways)

State 1

Reference State

This state represents the natural range of variability under pristine conditions. It is dominated by Rocky Mountain ponderosa pine with traces of Rocky Mountain juniper, singleleaf pinyon pine and white fir in the canopy. Primary natural disturbance mechanisms affecting this ecological site are wildfire, periodic drought, disease and insect attack. Interactions between disturbance regimes and weather events determine long-term plant community dynamics. Infrequent, yet periodic, wildfire is an important influence on the understory of mature ponderosa pine forests. Increased mortality following drought is likely caused by a combination of insect attack and disease. This ecological site is currently described by a one state model because additional states have not been identified at this time. If in the future additional stable states are identified on the landscape changes will be made to this model to reflect findings.

Community 1.1

Reference Plant Community

Figure 3. Mature Forest

The Reference Plant Community is dominated by Rocky Mountain ponderosa pines that have reached or are near maximal heights for the site, with a lesser component of white fir and Rocky Mountain juniper. Trace amounts of curl leaf mountain mahogany, Utah juniper, Great Basin bristlecone pine and singleleaf pinyon pine may also be found on this ecological site. An overstory canopy cover of about 20 to 35 percent is assumed to be representative of tree dominance on this site in the pristine environment. Black sagebrush is the principal understory shrub. Muttongrass and Ross’ sedge are the most prevalent understory grasses and grasslikes. Understory vegetation is strongly influenced by tree competition, overstory shading, duff accumulation, etc. Infrequent, yet periodic, wildfire is presumed to be a natural factor influencing the understory of mature ponderosa pine forests. Mature ponderosa pine trees are relatively resistant to cool, slow burning, wildfires through the understory due to their thick, insulating bark. This stage of community development is assumed to be representative of this forest site in the pristine environment.

Forest overstory. Tree canopy cover ranges from 20 to 35 percent. Overstory tree canopy composition is 85 percent ponderosa pine. White fir (Abies concolor) and Rocky Mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) each account for 15 percent and Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma), singleleaf pinyon pine (Pinus monophylla), curlleaf mountain mahogany (Cercocarpos ledifolius) and Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) may occur on the site, and collectively, comprise less than 10 percent of the total tree overstory canopy.

Forest understory. Understory vegetative composition is about 15 percent grasses, 15 percent forbs and 70 percent shrubs and young trees when the average overstory canopy is medium (20 to 35 percent). Average understory production ranges from 100 in unfavorable years to 250 pounds per acre in favorable years, with a medium canopy cover. Understory production includes the total annual production of all species within 4.5 feet of the ground surface. Understory production will decrease rapidly with canopy cover greater than 35 percent.

Figure 4. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 56 | 90 | 146 |

| Tree | 22 | 34 | 56 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 17 | 22 | 39 |

| Forb | 17 | 22 | 39 |

| Total | 112 | 168 | 280 |

Community 1.2

Herbaceous

This plant community is representative of an early-seral plant community phase. Vegetation is dominated by grasses and forbs under full sunlight. Standing snags remaining after disturbance have little or no affect on the composition and production of herbaceous vegetation, but can provide important wildlife habitat. This plant community is at-risk of invasion by non-natives. Non-native species take advantage of increased available critical resources following fire or other disturbance.

Community 1.3

Shrub-Herbaceous

This community phase is dominated by herbaceous vegetation and woody shrubs. Various amounts of tree seedlings (less than 20 inches in height) may be present up to the point where they are obviously a component of the vegetal structure. Sprouting shrubs, such as snowberry, purple sage and horsebrush, quickly recover and provide favorable sites for establishment of other shrub seedlings. Fast moving, low intensity fires result in the incomplete removal of sagebrush, allowing for direct reestablishment through on site seed.

Community 1.4

Sapling

This plant community is characterized by increasing woody perennials. In the absence of disturbance, the tree seedlings develop into saplings (20 inches to 4½ feet in height) with a canopy cover between 10 and 15 percent. Open canopy allows understory vegetation to be dominated by shrubs, grasses and forbs, in association with tree saplings. Sufficient time has passed for the complete recovery of sagebrush.

Community 1.5

Immature Forest

The visual aspect of this plant community is dominated by ponderosa pine greater than 4.5 feet in height. Young ponderosa pine are very susceptible to fire at this stage. Seedlings and saplings of ponderosa pine are common in the understory. Dominants are the tallest trees on the site; co-dominants are 65 to 85 percent of the highest of dominant trees. Understory vegetation is moderately influenced by a tree overstory canopy of about 15 to 20 percent. Black sagebrush and other shrubs serve as nurse plants for Ponderosa pine seedlings.

Community 1.6

Over-mature Forest

This stage is dominated by ponderosa pines that have reached maximal heights for the site. Understory vegetation is severely reduced or even absent due to tree competition, overstory shading, duff accumulation, etc. Few seedlings or saplings of ponderosa pine are found in the understory. Where white fir grows with ponderosa pine this community phase is characterized by an over abundance of suppressed white fir seedlings and saplings in the understory. This plant community experiences more runoff and less infiltration during precipitation events and is at-risk of soil loss due to surface erosion. Loss of understory vegetation reduces inputs of organic matter, water storage and soil stability.

Pathway 1.1a

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Stand replacing fire, disease, insect attack and/or prolonged drought.

Pathway 1.1c

Community 1.1 to 1.5

Thinning, partial mortality from pest attack or other small scale disturbance.

Pathway 1.1b

Community 1.1 to 1.6

Absence from disturbance and continued growth.

Pathway 1.2a

Community 1.2 to 1.3

Absence from disturbance and natural regeneration over time.

Pathway 1.3b

Community 1.3 to 1.2

Stand replacing fire, insect attack, disease and/or prolonged drought.

Pathway 1.3a

Community 1.3 to 1.4

Absence from disturbance and natural regeneration over time.

Pathway 1.4b

Community 1.4 to 1.2

Stand replacing fire, insect attack, disease and/or prolonged drought.

Pathway 1.4a

Community 1.4 to 1.5

Absence from disturbance and natural regeneration over time.

Pathway 1.5a

Community 1.5 to 1.1

Absence from disturbance and natural regeneration over time.

Pathway 1.5b

Community 1.5 to 1.2

Stand replacing fire, insect attack, diease and/or prolonged drought.

Pathway 1.6a

Community 1.6 to 1.2

Stand replacing fire, insect attack, disease and/or prolonged drought.

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Primary Perennial Grasses | 12–33 | ||||

| muttongrass | POFE | Poa fendleriana | 9–16 | – | ||

| Ross' sedge | CARO5 | Carex rossii | 2–9 | – | ||

| squirreltail | ELEL5 | Elymus elymoides | 2–9 | – | ||

| 2 | Secondary Perennial Grasses | 1–4 | ||||

| Indian ricegrass | ACHY | Achnatherum hymenoides | 1–2 | – | ||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 1–2 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | Perennial | 17–39 | ||||

| Nuttall's linanthus | LENUP | Leptosiphon nuttallii ssp. pubescens | 9–16 | – | ||

| Wyoming Indian paintbrush | CALI4 | Castilleja linariifolia | 2–9 | – | ||

| Clokey's fleabane | ERCL | Erigeron clokeyi | 2–9 | – | ||

| Cooper's rubberweed | HYCO2 | Hymenoxys cooperi | 1–3 | – | ||

| Virgin River cryptantha | CRVI5 | Cryptantha virginensis | 1–3 | – | ||

| pinewoods lousewort | PESE2 | Pedicularis semibarbata | 1–3 | – | ||

| dwarf phlox | PHCO11 | Phlox condensata | 1–3 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 4 | Primary Shrubs | 45–95 | ||||

| black sagebrush | ARNO4 | Artemisia nova | 17–40 | – | ||

| wax currant | RICE | Ribes cereum | 9–16 | – | ||

| mountain snowberry | SYOR2 | Symphoricarpos oreophilus | 9–16 | – | ||

| 5 | Secondary Shrubs | 11–45 | ||||

| mountain big sagebrush | ARTRV | Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana | 2–9 | – | ||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 2–9 | – | ||

| broom snakeweed | GUSA2 | Gutierrezia sarothrae | 2–9 | – | ||

| purple sage | SADO4 | Salvia dorrii | 2–9 | – | ||

| spineless horsebrush | TECA2 | Tetradymia canescens | 2–9 | – | ||

|

Tree

|

||||||

| 6 | Evergreen | 7–27 | ||||

| white fir | ABCO | Abies concolor | 2–9 | – | ||

| Rocky Mountain juniper | JUSC2 | Juniperus scopulorum | 2–9 | – | ||

| ponderosa pine | PIPOS | Pinus ponderosa var. scopulorum | 2–9 | – | ||

| Great Basin bristlecone pine | PILO | Pinus longaeva | 1–4 | – | ||

| singleleaf pinyon | PIMO | Pinus monophylla | 1–4 | – | ||

| curl-leaf mountain mahogany | CELE3 | Cercocarpus ledifolius | 1–4 | – | ||

| Utah juniper | JUOS | Juniperus osteosperma | 1–4 | – | ||

Table 7. Community 1.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| ponderosa pine | PIPO | Pinus ponderosa | Native | – | 60–70 | – | – |

| Rocky Mountain juniper | JUSC2 | Juniperus scopulorum | Native | – | 10–15 | – | – |

| white fir | ABCO | Abies concolor | Native | – | 10–15 | – | – |

| Utah juniper | JUOS | Juniperus osteosperma | Native | – | 1–3 | – | – |

| singleleaf pinyon | PIMO | Pinus monophylla | Native | – | 1–3 | – | – |

| curl-leaf mountain mahogany | CELE3 | Cercocarpus ledifolius | Native | – | 1–3 | – | – |

| Great Basin bristlecone pine | PILO | Pinus longaeva | Native | – | 1–3 | – | – |

Interpretations

Animal community

This site has limited suitability for livestock grazing, although animals may use this site during the hot summer months. Herbaceous forage production is quite low and the site is not easily accessed because due to steep slopes and lack of adequate water resources. The amount and nature of the understory vegetation in a forestland is highly dependent on the amount and duration of shade provided by the overstory canopy. Significant changes in kind and abundance of plants occur as the canopy changes, often regardless of grazing use.

Muttongrass is a valuable forage resource. It has been rated excellent forage for domestic cattle and horses. Ross’s sedge value as a forage plant varies depending on the site. It has been rated fair for domestic sheep, horses and cattle. Bottlebrush squirreltail is palatable to domestic livestock. Winter months show greatest use and it generally increases under heavy grazing. Dominant shrubs provide additional foraging resources on this ecological site. Black sagebrush is used by domestic livestock, it is considered to be highly palatable to domestic sheep. Cattle and domestic goats browse black sagebrush to a lesser degree. Wax currant provides poor to fair browse for domestic livestock, although it can be of great importance when little else is available. Mountain snowberry is readily eaten by all classes of livestock. Its ability to sprout allows it to persist and even increase under moderate browsing pressure.

Stocking rates vary with such factors as kind and class of grazing animal, season of use and fluctuations in climate. Actual use records for individual sites, a determination of the degree to which the sites have been grazed, and an evaluation of trend in site condition offer the most reliable basis for developing initial stocking rates. The forage value rating is not an ecological evaluation of the understory as is the range condition rating for rangeland. The forage value rating is a utilitarian rating of the existing understory plants for use by specific kinds of grazing animals.

Wildlife Interpretations: This area is high-use habitat for a variety of birds including, owls and goatsuckers, swifts, humming birds, wood peckers, flycatchers, nuthatches, thrushes and finches. It also has moderate forage value for big game during the summer, fall, and early winter, especially in areas with wax currant and other browse species in the understory. It is used occasionally by various other song birds, rodents and associated predators natural to the area. Many upland wildlife species find valuable foraging and habitat resources on this ecological site. Several wildlife species utilize bottlebrush squirreltail. It provides important forage for ground squirrels, cottontails and black-tailed jackrabbits and less important forage for mule deer. Muttongrass provides good forage ungulates. The seeds and leaves are also used by a variety of birds. Ross’s sedge provides occasional forage for mule deer. Dominant shrubs provide additional foraging resources on this ecological site. Black sagebrush provides important foraging resource for wild ungulates. In some areas it is the most important winter forage resource for mule deer and pronghorn antelope. Birds such as sparrows, sage thrashers and sage grouse use black sagebrush habitats extensively for food and cover. It is also used by rodents, small mammals and associated predators like golden eagles. Wax currant provides food and cover for wildlife. It is only fair to poor browse for deer, but is important on ranges were little else is available. Mountain snowberry provides important forage for deer on high elevation summer ranges. Snowberry is one of the first species to leaf out and therefore it is heavily used in the spring. Snowberry is capable of sprouting and therefore can persist and even increase under moderate browsing pressure. Prolonged browsing can result in reduced densities. Rocky Mountain juniper provides fair winter forage, excellent escape cover and good fawning cover. White fir provides spring forage for mule deer and good cover for many other wildlife species.

Hydrological functions

The soils associated with this site are characterized by very high runoff and very slow permeability. The potential for erosion is sever depending on the slope and amount of rock fragments on the soil surface.

Recreational uses

This site has high aesthetic value and provides a variety of recreational opportunities such as hiking, camping and permitted hunting, as well as, nature study and bird watching. Steep slopes and the fragile soil-vegetation complex, however, inhibit many other forms of recreation such as the use of off-road vehicles.

Wood products

Fuelwood Production: 27 to 43 cords per acre for stands averaging 40 to 50 feet in height and 200 years of age with a medium canopy cover (USDA 1935). There are about 213,750 gross British Thermal Units (BTUs) heat content per cubic foot of ponderosa pine wood. Solid wood volume in a cord varies but usually ranges from 65 to 90 cubic feet. Assuming an average of 75 cubic feet of solid wood per cord, there are about 16 million BTUs of heat value in a cord of ponderosa pine wood.

MANAGEMENT GUIDES AND INTERPRETATIONS

1. LIMITATIONS AND CONSIDERATIONS

a. Potential for sheet and rill erosion is

slight to moderate depending on slope.

b. Severe equipment limitations due to steep

slopes.

2. ESSENTIAL REQUIREMENTS

a. Protect soils from accelerated erosion.

b. Manage for protection of wildlife habitat.

c. Adequately protect from uncontrolled burning.

3. SILVICULTURAL PRACTICES

a. Traditional silvicultural treatments, such as harvest cutting, are not reasonably applied on this site due to poor site quality and severe limitations for equipment and tree harvest.

This site has potential for using hand-crews for thinning and improvement cuttings to remove diseased and overcrowded trees. Improvement cuttings cut selectively or in small patches size (dependent upon site conditions) to enhance forage production, wildlife habitat and forest health.

1) Thinning and improvement cutting - Removal of poorly formed, diseased and low vigor trees for fuelwood.

2) Slash Disposal - broadcasting slash improves reestablishment of native understory herbaceous species and establishment of seeded grasses and forbs after tree harvest.

b. Fire hazard - Fire usually not a problem in well-managed, mature stands.

Other products

The fruit of wax currant is used for making jam, jelly and pie. Indian tribes native to western America used currants for making pemmican and it is currently grown as an ornamental.

Table 8. Representative site productivity

| Common name | Symbol | Site index low | Site index high | CMAI low | CMAI high | Age of CMAI | Site index curve code | Site index curve basis | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ponderosa pine | PIPO | 38 | 50 | 29 | 38 | 100 | – | – |

Supporting information

Type locality

| Location 1: Clark County, NV | |

|---|---|

| Township/Range/Section | T15S R60E S34 |

| UTM zone | N |

| UTM northing | 4050052 |

| UTM easting | 657934 |

| Latitude | 36° 34′ 58″ |

| Longitude | 115° 14′ 4″ |

| General legal description | Sheep Peak USGS 7.5 minute topographic quadrangle. Approximately 0.8mi from Sheep Peak in the Sheep Range found in the Desert National Wildlife Refuge. Located north-east of Highway 95 and west of Highway 93 Clark County, Nevada. |

Other references

Fisher, R. and D. Binkley. 2002. Ecology and Management of Forest Soils. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Howard, J. L. 2003. Pinus ponderosa var. scopulorum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer) Available:http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Johnson, D.W., R.B. Susfalk, R.A. Dahlgren and J.M. Klopatek. 1998. Fire is more important than water for nitrogen fluxes in semi-arid forests. Environmental Science and Policy. 1:79-86.

Krugam, S.L. and J.L. Jenkinson. 2008. Pinus L. Woody Plant Seed Manual. USDA FS Agriculture Handbook 727. P819.

Lanner, R.M. 1984. Trees of the Great Basin. University of Nevada Press, Reno NV.

Scher, J.S. 2002. Juniperus scopulorum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Meyer, W.H. 1961. Yield of even-aged stands of ponderosa pine. USDA Tech Bull 630. (revised 1961).

Oliver, W.W. and R.A. Ryker. 1992. “Pinus ponderosa Dougl. ex Laws.” FS INFO-Intermoutain Monthly Alert. April 1992. No 131:413-423.

Spurr, S.H. and B.V. Barnes. 1964. Forest Ecology. John Wiley and Sons. New York, N.Y.

USDA. 1935. Instructions for the scaling and measurement of National Forest Timber Misc. Pub. 225.

USDA-NRCS. 2000 National Forestry Manual – Part 537. Washington, D.C.

USDA-NRCS. 2004 National Forestry Handbook, Title 190. Washington, D.C.

Zouhar, Kris. 2001. Abies concolor. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Contributors

PNOVAK-ECHENIQUE

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 03/11/2026 |

| Approved by | Kendra Moseley |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.