Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site DX034A01X126

Loamy Calcareous Green River Basin (LyCa GRB)

Last updated: 2/21/2025

Accessed: 03/18/2025

General information

Approved. An approved ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model, enough information to identify the ecological site, and full documentation for all ecosystem states contained in the state and transition model.

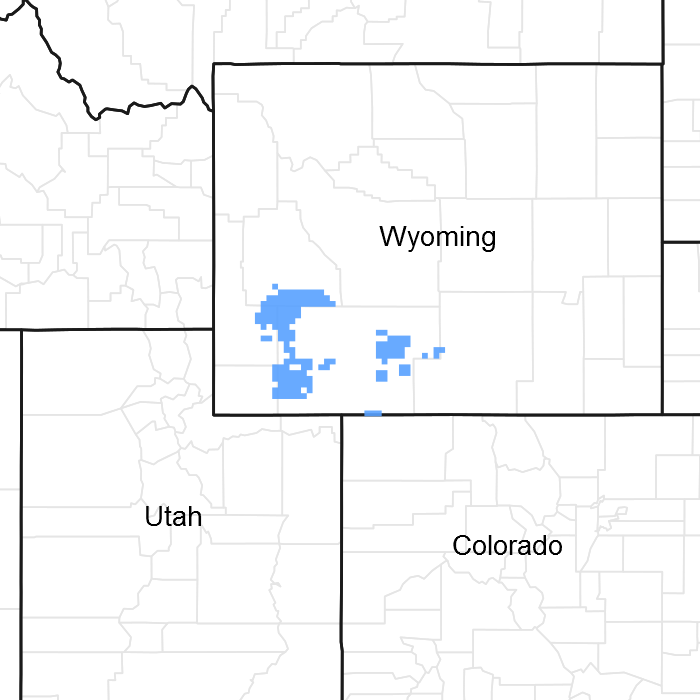

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 034A–Cool Central Desertic Basins and Plateaus

Site Name: Loamy Calcareous Green River Basin

Site Type: Rangeland

Site ID: R034AB126WY

Precipitation or Climate Zone: 7-9” P.Z.

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 34A-Cool Central Desertic Basins and Plateaus

For further information regarding MLRAs, refer to:

http://soils.usda.gov/survey/geography/mlra/index.html

Land Resource Unit (LRU) B (Green River Basin):

• Moisture Regime: ustic aridic

• Temperature Regime: frigid

• Dominant Cover: rangeland

• Representative Value (RV) Effective Precipitation: 7-9 inches

• RV Frost-Free Days: 60-90 days

Please refer to MLRA 34A LRU description document for a full description of LRU’s.

Classification relationships

Site Name: Loamy Calcareous Green River Basin

Site Type: Rangeland

Site ID: R034AB126WY

Precipitation or Climate Zone: 7-9” P.Z

National Vegetation Classification System (NVC):

Subclass

3.B Cool Semi-Desert Scrub & Grassland Subclass

Formation

3.B.1 Cool Semi-Desert Scrub & Grassland Formation

Division

3.B.1.Ne Western North American Cool Semi-Desert Scrub & Grassland Division

Macrogroup

3.B.1.Ne Great Basin & Intermountain Tall Sagebrush Shrubland & Steppe Macrogroup

Group

3.B.1.Ne Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis - Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata Tall Sagebrush Group

Association

3.B.1.Ne Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis / Achnatherum hymenoides Shrubland

Ecoregions (EPA):

Level I: 10 North American Deserts

Level II: 10.1 Cold Deserts

Level III: 10.1.4 Wyoming Basin

Ecological site concept

• Site does not receive additional water.

• Soils are:

o non saline , non-saline-sodic, and non-sodic

o moderately deep, deep, or very deep

o <5% cobble and gravel cover

o not skeletal within 20” of soil surface

o slight to no effervescence in surface mineral 4” (10 cm)

o have a CCE of 5-15% within top 10” (25cm) and >15% CCE below

o surface textures ranging from very fine sandy loam to light clay loam

o site has a “strong” diagnostic calcic horizon within 10-20 inches of the surface mineral

• Slope is 0-15%

• Clay content is <32% in surface mineral 6”

• Site does not exceed 35% clay in the argillic horizon.

The concept of this site is based on having a diagnostic calcic horizon (an illivual horizon in which secondary carbonate or other carbonates have accumulated to a significant extent), but does not have the presence of secondary or primary carbonates at the surface (strong to violent effervescent in the upper 4 inches (10 cm) of the profile). A similar site is the Limy site, which is strongly or violently effervescent to the soil surface and does not have the presence of a well-developed diagnostic calcic horizon. The reference plant community is a Wyoming Big Sagebrush/mixed grass plant community and with mismanagement or corrected management responds differently than the Loamy site, another similar site, in its potential plant community dynamics and productivity.

Associated sites

| DX034A01X122 |

Loamy Green River Basin (Ly GRB) |

|---|---|

| DX034A01X150 |

Sandy Green River Basin (Sy GRB) |

Similar sites

| R034AY162WY |

Shallow Loamy Green River and Great Divide Basins (SwLy) Similar in production and was previously correlated to these soils, but the soil description was too general ("acting shallow" or skeletal) |

|---|---|

| DX034A02X126 |

Loamy Calcareous Pinedale Plateau (LyCa PP) Has similar soil characteristics, but is wetter and slightly cooler |

| DX034A01X122 |

Loamy Green River Basin (Ly GRB) Previously correlated to these soils, but production is higher and lacks calcic horizon in the top 10-20 inches of the soil profile |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Artemisia tridentata var. wyomingensis |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Achnatherum hymenoides |

Legacy ID

R034AB126WY

Physiographic features

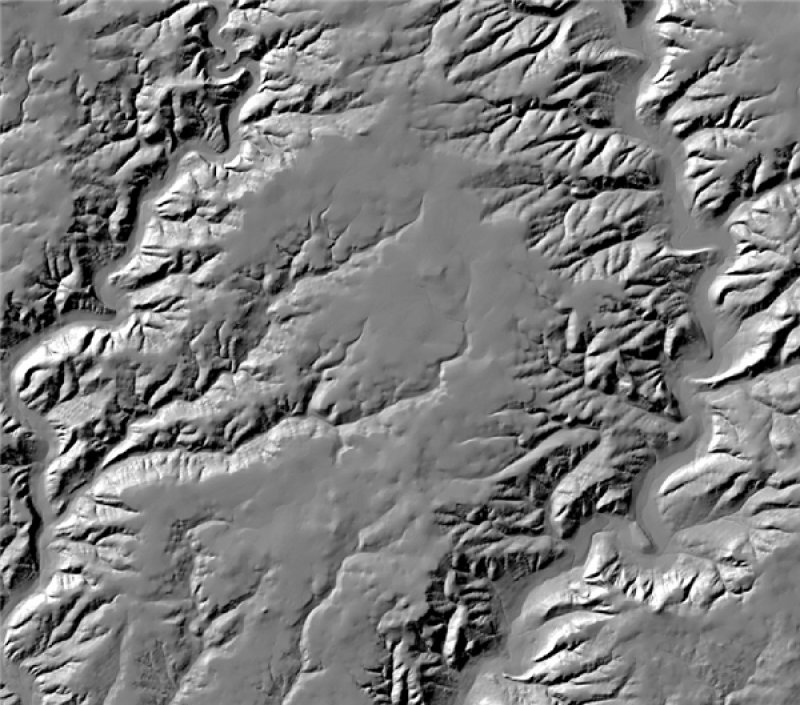

The Loamy Calcareous Green River Basin (LyC GRB) ecological site (R034AB126WY) is located within LRU “B” in MLRA “34.” This ecological site occurs in intermontane basin landscapes on hill, draw, pediment, and fan remnant landforms (see definitions below). The slope ranges from level to 15%. This site occurs on all aspects.

fan remnant – A general term for landforms that are the remaining parts of older fan-landforms, such as alluvial fans, fan aprons, inset fans, and fan skirts, that either have been dissected (erosional fan-remnants) or partially buried (nonburied fan-remnants). An erosional fan remnant must have a relatively flat summit that is a relict fan-surface.

intermontane basin – A generic term for wide structural depressions between mountain ranges that are partly filled with alluvium and called "valleys" in the vernacular.

hills – A landscape dominated by hills and associated valleys. The landform term is singular (hill).

Figure 2. Hill, Fan Remnant

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hill

(2) Fan remnant |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 1,768 – 1,981 m |

| Slope | 0 – 15% |

| Water table depth | 152 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

Annual precipitation ranges from 7-9 inches per year. Wide fluctuations may occur in yearly precipitation and result in more dry years than those with above normal precipitation. Temperatures show a wide range between summer and winter and between daily maximums and minimums. This is predominantly due to the high elevation and dry air, which permits rapid incoming and outgoing radiation. Cold air outbreaks in winter move rapidly from northwest to southeast and account for extreme minimum temperatures. Much of the precipitation accumulation (45%) comes in the winter in the form of snow (Oct to April). The wettest month is May (1.03 inches). The growing season is short (50-90 day average) and cool: primary growth typically occurs between May and June. The dominant plants (sagebrush and cool season grasses) are well adapted to these conditions. Daytime winds are generally stronger than nighttime and occasional strong storms may bring brief periods of high winds with gusts to more than 50 mph. Growth of native cool season plants begins about mid-April and continues to approximately early-July. Some green up of cool season plants may occur in September with adequate fall moisture.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 75 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 101 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 203 mm |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) GREEN RIVER [USC00484065], Green River, WY

-

(2) ROCK SPRINGS AP [USW00024027], Rock Springs, WY

-

(3) FONTENELLE DAM [USC00483396], Green River, WY

Influencing water features

None

Soil features

The soils of this site are deep to moderately deep (greater than 20" to bedrock), and well-drained. Textures range from loams to very fine sandy loam on the coarse end to clay loam (<30% clay content) on the heavy end. The most common textures include loam, silt loam, and sandy clay loam. A highly common scenario is to have a 1 to 3” cap of sandy loam over a sandy clay loam due to young soil development of weathered sandstone and shale parent materials.

Major Soil Series correlated to this site include: Pepal, Chickenhill, Luhon, Piezon, Jemdillon and Polaris

Typical taxonomy: Fine-loamy Ustic Haplocalcids

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

limestone, sandstone, and shale

(2) Slope alluvium – calcareous siltstone |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Loam (2) Sandy clay loam (3) Clay loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Moderately well drained to well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate to moderately rapid |

| Soil depth | 152 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 5% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0 – 5% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

15.24 – 18.29 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

15 – 50% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 4 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 8 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

7.4 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 10% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 40% |

Ecological dynamics

This ecological site is dominated (species composition by dry weight) by big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. Wyomingensis) and perennial cool-season grasses with forbs as a minor component. The site consists of five states: the Reference State (1), Grazing Resistant State (2), Bare Ground State (3), Disturbed State (4), and Highly Disturbed State (5). The Reference State is a collection of 3 distinct Plant Communities that exist on a continuum relative to disturbances, primarily grazing, pests, and drought with no disturbance causing successional changes as well over time. These Plant Communities represent the best adapted plant communities to the soils and climate found on the site, and they represent the best estimation of ecological dynamics present on this site at the time of European settlement. The Reference Plant Community (big sage/bunchgrass) of this site is dominated by Wyoming big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis) and cool-season perennial bunchgrass species, primarily Indian Ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides) and Needleandthread (Hesperostipa comata) with bottlebrush squirreltail (Elymus elymoides ssp. elymoides),and rhizomatous grasses like thickspike wheatgrass (Elymus lanceolatus ssp. lanceolatus) as a subdominant. Minor components include short-statured bunchgrasses such as Sandberg bluegrass, perennial forbs, and shrubs, including green rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus).

After a sagebrush killing disturbance (i.e. drought, insect, disease, herbivory, etc.), the Reference Plant Community transitions to the Bunchgrass Plant Community which is dominated by the mid-stature bunchgrasses mentioned above. Sagebrush is a minor component of this Plant Community, and only time without a sagebrush killing disturbance will advance this to the Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush which is an intermediate Plant Community described because of the time this site spends with this species composition, its value to resource managers, and it can be the most prone to some sagebrush killing disturbances, such as fire, which are thought be fairly infrequent on this site (Bukowski & Baker, 2013).

The Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush Plant Community, as a mid-seral stage, is often considered to have the most diversity and provide the most ecosystem services (i.e. wildlife habitat, livestock forage, etc.) in a multiple use management system.

Mid-stature bunchgrasses act as decreaser species in the Reference Community because they decrease in response to grazing pressure. Low stature bunchgrasses and rhizomatous grasses tolerate higher grazing pressure and grow on less fertile soils (Natural Resouces Conservation Service, 2007) than mid stature bunchgrasses. They often fill in the vegetation gaps created when mid stature bunchgrasses decline, hence they are collectively referred to as increaser species. Big sagebrush is the dominant shrub on this site. Wyoming big sagebrush is the sub-species present. Snow catchment is a significant hydrologic component of this site, and the hydrology changes when shrubs are removed from this site. There are often trace amounts of desert salt shrubs present on this site such as shadscale (Atriplex confertifolia), grey horsebrush (Tetradymia canescens), winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata), Gardner’s saltbush (Atriplex gardneri), and spiny hopsage (Grayia spinosa).

Prior to the introduction of livestock (cattle and sheep) during the late 1800s, elk, mule deer, and pronghorn grazed this ecological site, primarily as winter and transitional range (early spring, late fall). Significant livestock grazing has occurred on much of this ecological site for more than 100 years. The Trans-Continental Railroad in the 1860s brought the first herds, and homesteaders began settling the area through the turn of the century. Livestock grazing in this region has historically been a mix of cattle and sheep. In the Green River Basin moving south towards Farson and Rock Springs, historical livestock grazing was predominantly sheep grazing with some cattle grazing (USDI, 2015). Because of limited water availability, especially during the warmer months when snow was absent, grazing was predominantly winter sheep grazing with some winter cattle grazing in areas away from perennial streams and with shallow winter snow depths (USDI, 2015). This traditional use was reflected in the Rock Springs Grazing Association forming in response to restricting nomadic sheepherders from Colorado and Utah from using winter sheep range traditionally relied upon by Wyoming sheepherders (Tanner, 2016). Historical accounts prior to the Taylor Grazing Act indicated grazing was a free-range system where nomadic sheepherders grazed their sheep wherever they could when not restricted by cattlemen and homesteads (Tanner, 2016). As time progressed and water developments were constructed, the areas historically used by winter sheep slowly converted to more cattle grazing along with sheep grazing (USDI, 2015). Areas with available water during the summer changed to include cattle grazing during the warm months (USDI, 2015).

The northern portions of the Green River Basin starting in the South Pass area and the area branching outward toward the south had substantial emigrant trails crossing the region. Accounts estimate that from 1841 to 1869 between 300,000 to 350,000 emigrants followed the trail corridors on their way to Oregon, California, and Utah (Paolo Sioli, 1883). The southern portions of the Green River Basin had some trails (Cherokee Trail) used by stage coaches, and locals (Paolo Sioli, 1883).

Without ground disturbing activities, this site is relatively free of invasive weeds, but once mechanically or physically disturbed it is prone to weed invasion, primarily by annuals such as Halogeton (Halogeton glomeratus), lambsquarter (Chenopodium album), Russian thistle (Salsola kali), flixweed (Descurainia sophia), and kochia (Bassia scoparia). Soil disturbance can be caused by vehicles, equipment, high densities of animals (hoof-action), severe over-utilization of the herbaceous vegetation, or large amounts of bare ground created by extended drought conditions combined with over-utilization.

Perennial pepperweed (Lepidium latifolium) is a prevalent noxious weed in adjacent riparian areas. This mustard is usually found in riparian areas but has recently been observed invading adjacent upland sites. The Green River and many of its tributaries have significant perennial pepperweed infestations. It is said to be introduced to the area as a hay contaminant when ranches had to bring in hay from Utah, Idaho, and other areas during a drought in the 1970's. Another noxious mustard of concern is whitetop or hoary cress (Cardaria draba). This species is also found in many vegetation types within the Green River Basin, including irrigated hay meadows, roadsides, and disturbed rangelands. This disturbance can be from over-utilization of forage or plant thinning due to drought. This deep rooted perennial mustard completes its life cycle in early summer. Whitetop can tolerate the often highly alkaline soils of the Green River Basin.

Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), an invasive winter annual grass from the Mediterranean region, has been increasing in recent years. There are many challenges in controlling with this invasive grass and its impacts on plant communities, livestock grazing, and wildlife habitat. Recent publications have classified this soil temperature and moisture regime as moderately resilient and resistant to invasive species (Chambers, et al., 2016), but localized conditions on this ecological site result in relatively lower resilience, but higher resistance to invasion, compared to adjacent sites.

Plant Communities and Transition Pathways

Thorough descriptions of each state, transition, plant community, and pathway are found after the State and Transition Model (STM) diagram in this document. Experts base this model on available experimental research, field observations, professional consensus, and interpretations. While based on the best available information, the STM will change over time as knowledge of ecological processes increases.

Plant communities within the same ecological site differ across the LRU due to the naturally occurring variability in weather, soils, and aspect. Not all managers will choose the reference plant community as the management goal. Other plant communities may be desired to meet land management objectives. This is valid as long as the Rangeland Health attributes assessment departures are slight to moderate or none to slight for the Reference State. The biological processes on this site are complex; therefore, representative values are presented in a land management context. The species lists are representative and are not botanical descriptions of all species occurring, or potentially occurring, on this site. They are not intended to cover every situation or the full range of conditions, species, and responses for the site.

Both percent species composition by weight and percent canopy cover are used in this ESD. Most observers find it easier to visualize or estimate percent cover for woody species (trees and shrubs). Foliar cover drives the transitions between communities and states because of the influence of shade and interception of rainfall. Species composition by dry weight remains an important descriptor of the herbaceous community and of site productivity as a whole. Woody species are included in species composition by weight for the site. Calculating similarity index requires use of species composition by dry weight.

Although there is considerable qualitative experience supporting the pathways and transitions within the State and Transition Model (STM), quantitative information is lacking that specifically identifies threshold parameters between reference states and degraded states in this ecological site. For information on STMs, see the following citations: (Bestelmeyer, et al., 2003), (Bestelmeyer, Herrick, Brown, Trujillo, & Havstad, 2004), (Bestelmeyer & Brown, State-and-transition models 101: a fresh look at vegetation change, 2005), (Stringham, Kreuger, & Shaver, 2003).

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

States 2 and 5 (additional transitions)

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference

The Reference State consists of three Plant Communities: the Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass Community (1.1) the Bunchgrass/Big sagebrush Plant Community (1.2) and the Bunchgrass Community (1.3). Each community differs in percent composition of bunchgrasses and percent woody canopy cover. Forbs are a minor component on this site. Woody canopy cover is less than 25 percent. The Loamy Calcareous site potential is slightly less than the Loamy site in this LRU, due to the restrictive nature of the shallow calcic horizon that occurs in it. The diversity in plant species allows for drought tolerance, and natural plant mortality is very low. These plants have strong, healthy root systems that allow production to increase significantly with favorable moisture conditions. The dominant shrub species is Wyoming Big Sagebrush in the Reference State (1). Two important processes occurring in this state result in plant community changes within Reference State: sagebrush killing disturbances (browse, insects, and drought) and long periods of time without those disturbances. This process of plant community change over time is generally referred to as “natural succession.” The shift from the Bunchgrass Plant Community (1.3) to the Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush Plant Community (1.2) and subsequently to the Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass Plant Community is dependent on an increase of woody cover. Without sagebrush killing disturbance, shrubs will increase on this ecological site even with proper grazing management. Improper grazing management may accelerate the rate of increase for woody species and/or result in higher shrub canopy cover than in the Reference State. The shift from the Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass or Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush Plant Communities is dependent on sagebrush killing disturbances such as drought, herbivory, disease and insect outbreaks. Management actions can and are often used to mimic these processes through mechanical and chemical treatments. The Reference State is well adapted to Cool Central Desertic Basins and Plateaus climatic conditions. The diversity in plant species allows for drought tolerance, and plant mortality is low. These plants have strong, healthy root systems that allow production to increase significantly with favorable moisture conditions. Abundant plant litter is available for soil building and moisture retention and is properly distributed with very little movement off-site. Biological soil crusts play an important role in protecting the soil surface as well as carbon, nutrient, and water cycles, particularly moss and lichen under the sagebrush canopy and cyanobacteria in the interspaces (Natural Resources Conservation Service, 1997) (Rosentrater & M. Bowker, 2007). They are a source of carbon to soils, and not only do they convert atmospheric nitrogen into bio-available nitrogen, but they also secrete compounds that increase the bio-availability of phosphorus (Rosentrater & M. Bowker, 2007). This State provides for soil stability and a properly functioning hydrologic cycle. The soils associated with this site hold moderately large amounts of soil moisture, providing a very favorable soil-water-plant relationship. Plant community phases can occur in large contiguous blocks or in a small to large mosaic pattern, but typically this plant community is maintained within a larger mosaic at the landscape level with the other plant communities phases identified in the Reference State (Bukowski & Baker, 2013). Mechanical and chemical treatment of shrubs have replaced natural sagebrush killing events in many cases. However, chemical treatments impact nontarget species, particularly broad-leafed species (forbs and shrubs) differently than natural. Chemical treatment of sagebrush with tebuthiuron can have impacts the understory, depending on application rate (Wyoming Wildlife Consultants, LLC, 2009). Many historical treatments with continuous grazing both pre- and post-treatment have resulted in a transition to the Disturbed State. Good historical records of the pre-treatment State are not available, but it is presumed that they were already in the Grazing Resistance State, and thus this result may not apply to treatments planned on communities in the Reference State.

Community 1.1

Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass

Figure 7. 1.1

This community can occur over time without disturbance (i.e. “natural succession”), or it can be accelerated with moderate herbaceous grazing pressure. Wyoming big sagebrush is dominant with sagebrush foliar cover ranging from 25% to 35%. At this level of sagebrush cover in this precipitation zone, there is competition between the shrub over-story and the herbaceous understory (Winward, 2007). A Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass Community with a degraded understory is an “at-risk” community, particularly when occurring homogeneously across the landscape. There are generally few canopy gaps, and most basal gaps are moderate (3-6 feet). Rock cover on the soil surface is low. Many plant interspaces have canopy or litter cover. Production of grasses is relatively much lower than in the Bunchgrass Community (1.3) and slightly lower than in the Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush Community (1.2).

Figure 8. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 112 | 224 | 280 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 90 | 179 | 224 |

| Forb | 22 | 45 | 56 |

| Total | 224 | 448 | 560 |

Table 6. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 0% |

| Forb foliar cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 15-30% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 20-30% |

Table 7. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0% |

| Forb basal cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 25-40% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 20-30% |

Figure 9. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). WY0401, 7-9GR, UPLAND SITES. ALL UPLAND SITES.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Community 1.2

Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush

Figure 10. 1.2

This community can occur after a sagebrush thinning event, such as drought, insects, or disease, or it can take longer to occur after a stand replacing event. Mid-stature bunchgrasses co-dominate with Wyoming big sagebrush, with sagebrush cover ranging from 5% to 15%. At this sagebrush canopy level in this precipitation zone, there is little if any competition between the shrub overstory and the herbaceous understory. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that the understory receives more benefit from the sage over-story than negative effects. (Winward, 2007) There are generally few canopy gaps, and most basal gaps in the 1-2 foot and 2.1-3 foot categories. Rock cover on the soil surface is low to moderate. Many plant interspaces have canopy or litter cover. Production of grasses is slightly less than in the Bunchgrass Community (1.3), but shrub production is higher.

Figure 11. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 112 | 224 | 280 |

| Shrub/Vine | 90 | 179 | 224 |

| Forb | 22 | 45 | 56 |

| Total | 224 | 448 | 560 |

Table 9. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 0% |

| Forb foliar cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 15-30% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 20-30% |

Table 10. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0% |

| Forb basal cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 25-40% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 20-30% |

Figure 12. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). WY0401, 7-9GR, UPLAND SITES. ALL UPLAND SITES.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Community 1.3

Bunchgrass

The Bunchgrass Community (1.3) is dominated by mid-stature cool-season bunchgrasses mixed with a minor component of forbs and shrubs. Wyoming big sagebrush and desert salt shrubs are present as a part of the community, but they are a minor component with 0 to 5% foliar cover. Sprouting shrubs such as green rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus) may appear more visible and dominant with reduced sagebrush cover, but they are not dominant compared to the herbaceous component. Biological soil crusts are temporarily decreased due to disturbance, but soil protection is provided by high amounts of litter from the herbaceous component. The Bunchgrass Community (1.3) generally occurs immediately following a stand replacing sagebrush killing event such as moderate drought, insects, or winter browse. Fire is not a common disturbance on this site. Chemical, mechanical, and biological control can be effective tools to achieve this plant community, when used in conjunction with a grazing system that alters the timing and intensity of grazing and provides periodic rest/deferment during the critical growth period.

Figure 13. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 11. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 146 | 291 | 336 |

| Shrub/Vine | 56 | 112 | 168 |

| Forb | 22 | 45 | 56 |

| Total | 224 | 448 | 560 |

Table 12. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 0% |

| Forb foliar cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 15-30% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 20-30% |

Table 13. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0% |

| Forb basal cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 25-40% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 20-30% |

Figure 14. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). WY0401, 7-9GR, UPLAND SITES. ALL UPLAND SITES.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

The trigger for a community shift from the Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass Community (1.1) to the Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush Community (1.2) is a sagebrush thinning event, such as drought, insects, disease, chemical, mechanical or biological control of sagebrush that favors the existing herbaceous vegetation while only removing a portion of the sagebrush canopy so that 5-15% sagebrush cover remains. Indicators include the increase in density and vigor of mid-stature bunchgrasses to the point that they co-dominate species composition by weight with Wyoming big sagebrush.

Pathway 1.1B

Community 1.1 to 1.3

The trigger for a community shift from the Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass Community (1.1) to the Bunchgrass Community (1.3) is a stand replacing sagebrush killing event, such as fire, drought, insect outbreaks, disease, chemical, mechanical or biological control of sagebrush that favors the existing herbaceous vegetation and removes sagebrush canopy to <5%. Fire is not typically a driver, but can occur, particularly at the edge of the site concept and when high production years are followed by drought on ungrazed sites. Indicators include decreased sagebrush cover and the increase in density and vigor of mid-stature bunchgrasses to the point that they dominate species composition by weight.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

The trigger for a community shift from the Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush Community (1.2) to the Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass Community (1.1) is natural succession, or lack of disturbance over time. Indicators include an increase in shrub cover and proportional decline in overall under-story.

Pathway 1.2B

Community 1.2 to 1.3

The trigger for a community shift from the Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush Community (1.2) to the Bunchgrass Community (1.3) is a sagebrush killing event, such as fire, drought, chemical, mechanical or biological control of sagebrush that favors the existing herbaceous vegetation. Indicators include an increase in density and vigor of mid-stature bunchgrasses to the point that they dominate species composition by weight.

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.2

The trigger for a community shift from the Bunchgrass Community (1.3) to the Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush Community (1.2) is natural succession, or lack of disturbance over time. Indicators include an increase in shrub cover and relative decline in the herbaceous under-story. Natural succession results in sagebrush cover increasing in response to annual climatic differences and a certain amount of herbivory. Succession can be accelerated with proper herbaceous grazing (fully stocked and a system that varies the time and timing of grazing to provide for periodic deferment during the critical growth period) and natural events such as drought/wet cycles.

State 2

Grazing Resistant

The Grazing Resistant State is characterized an herbaceous component dominated by thickspike wheatgrasses Sandberg bluegrass and/or mat-forming forbs, with limited mid-stature bunchgrasses. Once mid-stature bunchgrasses become scarce, it is unlikely there will be sufficient reproductive capability (seed source, tillering, or re-sprouting) to recover dominance in a reasonable time frame without extra energy being added to the system (Cagney, et al., 2010). The plant community is highly resistant to changes in composition, due to the dominance and competition of grazing tolerant species. However, the community can be restored back to the Reference State (1) with sagebrush treatment (chemical, mechanical, or biological brush management) and grazing deferment followed by a grazing system that allows periodic rest during the critical growth period. Seeding maybe needed in some instances to achieve desired results.

Community 2.1

Big Sagebrush/Thickspike Wheatgrass

Figure 15. 2.1

Wyoming big sagebrush dominates with cover as high as 25% or greater. Areas that catch and retain snow are more likely to have higher shrub cover. Biological soil crusts have diminished in the plant interspaces, but are still present under the sagebrush canopy and play an important role in protecting the soil surface as well as carbon, nutrient, and water cycles. Productivity is highly variable and fluctuates drastically in response to drought and wet cycles. Production is lower than in Reference State (1), leading to lower soil organic matter content and therefore lower soil stability than in the Reference State. Ground cover is still high, but infiltration is lower than in the Reference State and the hydrologic function is impaired due to decreased soil organic matter.

Figure 16. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 14. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 56 | 168 | 224 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 45 | 135 | 179 |

| Forb | 11 | 34 | 45 |

| Total | 112 | 337 | 448 |

Figure 17. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). WY0401, 7-9GR, UPLAND SITES. ALL UPLAND SITES.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Community 2.2

Thickspike Wheatgrass/Big Sagebrush

Thickspike wheatgrass (Elymus lanceolatus ssp. lanceolatus) dominates, and Wyoming big sagebrush foliar cover is typically 5% to 15%. This plant community phase occurs if there is a sagebrush killing event after the herbaceous component has already been degraded. Biological soil crusts have greatly diminished, further exposing the soil surface to erosional forces as well as impairing carbon, nutrient, and water cycles. Productivity is highly variable and fluctuates drastically in response to drought and wet cycles. Production is lower than in Reference State (1), leading to lower soil organic matter content and therefore lower soil stability than in the Reference State. Hydrologic function is impaired due to decreased soil organic matter.

Figure 18. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). WY0401, 7-9GR, UPLAND SITES. ALL UPLAND SITES.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

The trigger for a community shift from the Big Sagebrush/Thickspike Wheatgrass Community (2.1) to the Thickspike Wheatgrass/Big Sagebrush Community (2.2) is a sagebrush killing event such as drought, insects, and disease, chemical, mechanical or biological control of sagebrush that favors the existing herbaceous vegetation and removes sagebrush canopy along with continuous spring grazing during the critical growth period. Without a change in grazing regime, the existing understory will respond, but mid-stature bunchgrasses will not increase.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

The trigger for a community shift from the Thickspike Wheatgrass/Big Sagebrush Community (2.2) to the Big Sagebrush/Thickspike Wheatgrass Community (2.1) is time without sagebrush killing disturbances. This shift can be accelerated with high utilization levels by herbaceous grazers, particularly during the critical growth period.

State 3

Bare Ground

This state contains one community, the Big Sagebrush/Bare Ground Community (3.1). It is characterized by very old sagebrush stands with very little understory between the sagebrush canopy. Bare ground patch sizes are very large and comprise the majority of the interspaces between sagebrush plants. Communities in the Bare Ground State (3) have crossed a threshold (T1-3 or T2-3) due to degradation of dynamic soil properties such as organic matter, fertility, and infiltration caused by soil erosion. Soil erosion affects the hydrology, soil chemistry, soil microorganisms, and soil physics to the point where intensive restoration is required to return the site to another state. Simply changing grazing management will not create sufficient change to restore the site within a reasonable time period. It will require a considerable input of energy to move the site back to the Reference State (1). The Bare Ground State (3) is at moderate risk of weed invasion due to the high percentage of bare ground. Many invasive species are adapted to low soil fertility, high soil temperatures and low soil moisture content. Furthermore, this state is at risk of transitioning to the Disturbed State (4) if mechanical treatments are applied without consideration for seeding or grazing management.

Community 3.1

Big Sagebrush/Bare Ground

Figure 19. 3.1

Herbaceous cover in the Big Sagebrush/Bare Ground Community (3.1) is significantly reduced. Annual production is approximately half of the Bunchgrass Plant Community (1.1). Perennial bunchgrasses (e.g., Indian ricegrass, bottlebrush squirreltail, and needleandthread) exist only in low densities and protected under the sagebrush canopy. This community tends to be dominated by Wyoming big sagebrush (>25% cover) and bare ground often exceeds 50% in large connected patches in the interspaces of the shrub canopy (>6 foot canopy gap common). The majority of annual production is from big sagebrush so this site provides very little value for grazing. Sparse vegetation creates low levels of foliar and basal cover. This, in turn, leads to low litter production, which is combined with reduced ability to retain litter on site. Soil is exposed to wind and water erosion in the plant interspaces. These factors combine to create a decrease in soil organic matter. Reduced litter cover, combined with reduced herbaceous cover, results in higher soil temperature, poor water infiltration rates, and high evaporation, thus favoring species which are more adapted to drier conditions. Soil fertility is reduced, soil compaction is increased, and resistance to soil surface erosion has declined compared to the other states. This community has lost most, if not all, of the attributes of a functioning, healthy rangeland, including good infiltration, minimal erosion and runoff, nutrient cycling, and energy flow. Biological soil crusts have greatly diminished, further exposing the soil surface to erosional forces as well as impairing carbon, nutrient, and water cycles.

Figure 20. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). WY0401, 7-9GR, UPLAND SITES. ALL UPLAND SITES.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

State 4

Disturbed

This state contains one plant community, the Rabbitbrush/Rhizomatous wheatgrass plant community. It is characterized by rabbitbrush dominance and a perpetual state of disturbance as evidenced in pasture corners, gravel pits and areas repeatedly treated to kill sagebrush.

Community 4.1

Sprouting Shrub/Thickspike Wheatgrass

Figure 21. 4.1

The Sprouting Shrub/Thickspike Wheatgrass Community (4.1) is in a perpetual state of disturbance. The disturbance regime of the site has been accelerated often with the addition of ground disturbing activities (i.e. gravel pits, pasture corners where livestock are gathered, continual sagebrush removal techniques, and/or consecutive fires. Biological soil crusts are non-existent, further exposing the soil surface to erosional forces as well as impairing carbon, nutrient, and water cycles. Seeding may be used to restore functional structural groups, but rabbitbrush is likely to continue as a dominant shrub into the foreseeable future with no restoration pathway identified at this time due to irreversible changes to soil dynamic properties (structure, organic matter, infiltration, bulk density, and/or water holding capacity) unless disturbance ceases.

Figure 22. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). WY0401, 7-9GR, UPLAND SITES. ALL UPLAND SITES.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

State 5

Highly Disturbed

All sites may transition to this state following a severe soil disturbance such as oil and gas development or surface mining extraction.

Community 5.1

Annuals/Bare Ground

The Annuals/Bare Ground Community (5.1) occurs after severe disturbance, most often physical soil disturbance that removes all topsoil, but it can also occur as a transition from the Bare Ground State (3) after severe drought, flooding, pests, or disease kills sagebrush, leaving the site with no perennial vegetation. Populations of annual and/or invasive weeds reach critical levels and impact the ecological processes on the site until restoration of the site occurs. As part of succession, all sites that are severely disturbed go through this plant community as part of the restoration process, but the time in this plant community phase is largely dependent on the use of restoration Best Management Practices (BPMs) and climate cycles. Biological soil crusts are non-existent, further exposing the soil surface to erosional forces as well as impairing carbon, nutrient, and water cycles.

Community 5.2

Reclaimed

The Reclaimed Community (5.2) is highly variable based on weather conditions during restoration activities, the management practices used to implement the restoration, the seed mix, and timing/method of stockpiling topsoil during the disturbance. The most common scenario is a reclaimed oil and gas well pad planted to crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum) without appropriate topsoil stockpiling. If topsoil is stockpiled, it may have been stored for too long and/or stored too deep resulting in fewer soil microorganisms. Over time, Wyoming big sagebrush will spread into the reclaimed area, but the understory will be dominated by introduced species. Biological soil crusts are minimal, further exposing the soil surface to erosional forces as well as impairing carbon, nutrient, and water cycles.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

The drivers for transition from the Reference State to the Grazing Resistant State are continuous low intensity spring grazing and/or severe drought. Continuous spring grazing and/or extended drought can lead to a decline in palatable mid-stature bunchgrasses. Indian ricegrass, a short-lived perennial that requires more frequent seed production to provide an adequate seedbank (Natural Resources Conservation Service). Bottlebrush squirreltail will also decline with grazing pressure and lack of disturbances that kill sagebrush. Needleandthread is more grazing tolerant, but will eventually decline in plant density and vigor. As bunchgrasses diminish or die during periods of stress, low- stature bunchgrasses and rhizomatous grasses gain a competitive advantage, creating a shift in species composition towards less productive, shorter species. While bare ground may not change significantly, the pattern of bare ground will shift to larger gaps in the canopy and fewer herbaceous plants between shrubs. Many of the remaining desirable bunchgrasses will be only found in the understory of the sagebrush canopy. Once mid-stature bunchgrass species become scarce, it is unlikely that they have sufficient reproductive capability (seed source, tillering, or re-sprouting) to recover dominance in a reasonable time frame without management changes and extra energy being added to the system (Cagney, et al., 2010). When the understory vegetation has been degraded to this point, the transition to the Grazing Resistant State (2) can occur from either the Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush Plant Community (1.2) or the Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass Plant Community (1.1). The transition is not dependent on the increase of shrub cover, but rather the lack of mid-stature bunchgrasses in the canopy interspaces. Management should focus on grazing management strategies that will prevent further degradation. This can be achieved through a grazing management scheme that varies the season of use to provide periodic deferment during the critical growth period (roughly May-June). Forage quantity and/or quality in the Grazing Resistant State (2) may be substantially reduced compared to the Reference State, and will dramatically fluctuate in dry vs. wet years.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The drivers for transition from the Reference State to the Bare Ground State is continuous high intensity/long duration grazing. Drought can accelerate this transition. Indicators of this transition include significant decline in herbaceous cover or total annual aboveground biomass production falls below 200 pounds per acre. The trigger of this transition is the loss of understory, which creates open spots of with bare soil between the sagebrush canopy (>6 foot gap size). Soil erosion is accompanied by decreased soil fertility and infiltration, triggering the transition to the Eroded State. Several other key factors signal the approach of a threshold: an increase in soil physical crusting, a decrease in soil surface aggregate stability, and/or evidence of erosion, including water flow patterns, development of pedestals, and litter movement.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

The causes for transition from the Reference State to the Disturbed State (T1C) is an increase in the disturbance cycle (i.e. grazing, drought, fire, mechanical, chemical or biological treatments), often in combination with grazing management that does not provide periodic deferment during the critical growth period. The transition can occur if multiple soil disturbing activities occur over a relatively short time period, effectively decreasing the disturbance return interval. This could be high intensity/high frequency grazing, machinery, and/or multiple sagebrush treatments. Indicators include an increase in rabbitbrush to dominant levels in the plant community due to ground disturbance that could be either natural (i.e. water movement) or manmade (i.e. high density/high frequency stocking, mechanical treatments or heavy equipment operations). If introduced to the site, invasive species, such as cheatgrass, may be present, but do not often dominate the site. To prevent this transition, the site will require proper reclamation after disturbance using the most current science and technology available to restore native vegetation and prevent invasive dominance. In cases where topsoil loss occurs, it may be impossible to prevent this transition. Long-term stressors on native species (e.g., improper grazing management, and drought) will alter plant community composition and production over time and may hasten the transition to the Disturbed State (4), but the main trigger is ground disturbance. The resulting lower biomass production, reduced litter, and increased bare ground in this community can promote invasion of undesirable species, but soil chemistry results in more resistance to invasives compared to other sites.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

The drivers for this restoration pathway are reduction of woody species and restoration of native herbaceous species by mechanical or chemical treatment of sagebrush, and grazing rest or deferment. If some mid- stature bunchgrasses remain under the sage canopy, light to moderate stocking with periodic critical growth period rest every 2 or 3 years can move the site back to the Reference State (1) combined with a mechanical or chemical sagebrush treatment. Most probable restoration pathway is from Big Sagebrush/Rhizomatous Wheatgrass Community (2.1) to the Bunchgrass Community (1.3). This could take multiple generations of management or could be accelerated with rest or deferment combined with successive wet springs conducive to seed germination and seedling establishment. (Derner, Schuman, Follett, & Vance, 2014). Seeding may be needed to achieve desired results, if seedbank has been depleted.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

The driver for transition from the Grazing Resistant State to the Bare Ground State (T2-3) is continuous high intensity grazing from the Big Sagebrush/Thickspike Wheatgrass Community (2.1). Examples include calving pastures and small acreage horse pastures where rotational grazing is not employed, and stocking densities are high. Extended drought periods accelerate this transition. Indicators include very old sagebrush stands with very little understory between the sagebrush canopy. Bare ground patch sizes are very large (>6 foot canopy gaps comprising >30% of transect) and comprise the majority of the interspaces between sagebrush plants.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

The driver for transition from the Grazing Resistant State to the Disturbed State (T2-4) is an increase in the disturbance cycle (i.e. drought, mechanical, chemical, biological treatments) and/or continuous high intensity grazing. Examples include pasture corner gates, calving pastures and small acreage horse pastures where rotational grazing is not employed combined with sagebrush treatment (mechanical, chemical, or biological). High stocking densities are soil disturbing, and adding sagebrush treatment(s) to this regime result in an increase in the disturbance cycle. A non-grazing influenced example would be an abandoned gravel pit. Removal of shrubs without proper grazing management can lead to an increase in bare ground and erosion of the upper soil horizon, and the site can degrade to the Disturbed State (4). Consequences of this transition are decreased soil fertility, soil erosion, soil crusting, and decrease of soil surface aggregate stability. Indicators of the Disturbed state are a shift in shrub dominance away from sagebrush and toward sprouting shrubs such as green rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus) or shadscale (Atriplex confertifolia).

Transition T2C

State 2 to 5

The driver for transition from the Grazing Resistant to the Highly Disturbed State (T2-5) is a topsoil removing event with mechanical equipment. Examples include construction sites, oil and gas activity, and borrow areas.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 2

Restoration from the Bare Ground State (3) to the Grazing Resistant State (2) is possible with mechanical, biological and chemical treatments and temporary rest or deferment post-treatment. Due to loss of soil fertility, structure, and organic matter, reference community plants are slow to repopulate the site. Success of this restoration is highly dependent upon climatic factors, and may require successive wet years. This restoration pathway is often unintentionally achieved when the goal is the Reference State (1) because post-treatment management is not sustained in a manner that allows frequent critical growth period rest and/or use levels and recovery periods are not adequate to sustain mid-stature bunchgrasses.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

The driver for this transition is multiple sagebrush killing events in rapid succession outside the normal disturbance regime for this site (see Reference State for discussion). It could be mechanical (including shallow disturbances with heavy equipment/construction or a mowing/chaining/harrow type sage treatment), chemical (including 2,4-D or tebuthiuron), or biological (including browse and/or insects).

Transition T3B

State 3 to 5

The driver for transition to the Highly Disturbed State (5) is a topsoil removing event with mechanical equipment, but it can also occur after severe drought, flooding, pests, or disease kills sagebrush, leaving the site with no perennial vegetation. Examples include construction sites, oil and gas activity, and borrow areas. Evidence of climate as a cause for this transition has been captured after the 2012 drought (Clause & Randall, 2014).

Transition T4A

State 4 to 5

The driver for transition from the Disturbed State to the Highly Disturbed State (T4-5) is a topsoil removing event with mechanical equipment. Examples include construction sites, oil and gas activity, and borrow areas.

Restoration pathway R5A

State 5 to 2

The Highly Disturbed State (5) is often restored to the Grazing Resistant State (2) unintentionally when inappropriate seed mixes are used and post-seeding grazing does not provide adequate and periodic critical growth period rest. There is low potential for recovery without significant inputs of energy and resources if topsoil has been removed. Seed mixes that mimic an adjacent “reference area” rather than the site potential as described in the Reference State (1) will often result in a plant community resembling the Grazing Resistant State (2) due to pre and post-seeding grazing management of the area.

Restoration pathway R5B

State 5 to 3

The Highly Disturbed State (5) can transition the Bare Ground State (3) if disturbed areas result in total topsoil removal and are abandoned and climate is favorable for sagebrush seedling establishment. Wyoming big sagebrush will eventually colonize the site, but because soil conditions are severely altered, little to no under-story can be found. An example of this transition can be found on abandoned oil and gas wells that are 30+ years old where topsoil was not stockpiled and re-spread on the site after proper contouring and ripping, and either no seeding was done or the planting was a failure.

Restoration pathway R5C

State 5 to 4

The Highly Disturbed State (5) can transition the Disturbed State (4) if disturbed areas result in only partial topsoil removal, leaving rootstock available for sprouting shrubs such as rabbitbrush or shadscale. This is common for gravel pits and areas disturbed as stockpile areas where soil is placed on the area for any amount of time, and then removed with equipment that scrapes some of the soil surface during the removal process.

Additional community tables

Table 15. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Perrenial Mid-Stature Cool Season Grasses | 49–90 | ||||

| Indian ricegrass | ACHY | Achnatherum hymenoides | 45–90 | 10–20 | ||

| squirreltail | ELELE | Elymus elymoides ssp. elymoides | 22–67 | 5–15 | ||

| needle and thread | HECO26 | Hesperostipa comata | 4–45 | 1–10 | ||

| Montana wheatgrass | ELAL7 | Elymus albicans | 0–45 | 0–10 | ||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 0–45 | 0–10 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| 2 | Rhizomatous Grasses | 22–45 | ||||

| thickspike wheatgrass | ELLAL | Elymus lanceolatus ssp. lanceolatus | 22–45 | 5–10 | ||

| 3 | Misc. Grasses/Grasslikes | 22–45 | ||||

| plains reedgrass | CAMO | Calamagrostis montanensis | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| needleleaf sedge | CADU6 | Carex duriuscula | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| threadleaf sedge | CAFI | Carex filifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| Grass, perennial | 2GP | Grass, perennial | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 4 | Perennial Forbs | 22–40 | ||||

| rosy pussytoes | ANRO2 | Antennaria rosea | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Indian paintbrush | CASTI2 | Castilleja | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| pale bastard toadflax | COUMP | Comandra umbellata ssp. pallida | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| tapertip hawksbeard | CRAC2 | Crepis acuminata | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| larkspur | DELPH | Delphinium | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| fleabane | ERIGE2 | Erigeron | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| buckwheat | ERIOG | Eriogonum | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| flaxleaf plainsmustard | SCLI | Schoenocrambe linifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| scarlet globemallow | SPCO | Sphaeralcea coccinea | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| stemless mock goldenweed | STAC | Stenotus acaulis | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Townsend daisy | TOWNS | Townsendia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| hollyleaf clover | TRGY | Trifolium gymnocarpon | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| clover | TRIFO | Trifolium | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| deathcamas | ZIGAD | Zigadenus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Forb, perennial | 2FP | Forb, perennial | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| beardtongue | PENST | Penstemon | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| spiny phlox | PHHO | Phlox hoodii | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| longleaf phlox | PHLOL2 | Phlox longifolia ssp. longifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| desertparsley | LOMAT | Lomatium | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| hoary tansyaster | MACA2 | Machaeranthera canescens | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| evening primrose | OENOT | Oenothera | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| twinpod | PHYSA2 | Physaria | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| bladderpod | LESQU | Lesquerella | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| springparsley | CYMOP2 | Cymopterus | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| draba | DRABA | Draba | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| sego lily | CANU3 | Calochortus nuttallii | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| rayless tansyaster | MAGR2 | Machaeranthera grindelioides | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| 5 | Annual Forbs | 0–4 | ||||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| rockjasmine | ANDRO3 | Androsace | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| bushy bird's beak | CORA5 | Cordylanthus ramosus | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 6 | Shrubs | 90–157 | ||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush | ARTRW8 | Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis | 90–157 | 20–25 | ||

| 7 | Misc. Shrubs | 40–67 | ||||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| spiny hopsage | GRSP | Grayia spinosa | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| winterfat | KRLA2 | Krascheninnikovia lanata | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| granite prickly phlox | LIPU11 | Linanthus pungens | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| bud sagebrush | PIDE4 | Picrothamnus desertorum | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| greasewood | SAVE4 | Sarcobatus vermiculatus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| spineless horsebrush | TECA2 | Tetradymia canescens | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| shortspine horsebrush | TESP2 | Tetradymia spinosa | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Shrub (>.5m) | 2SHRUB | Shrub (>.5m) | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| shadscale saltbush | ATCO | Atriplex confertifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Gardner's saltbush | ATGA | Atriplex gardneri | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| plains pricklypear | OPPO | Opuntia polyacantha | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

Table 16. Community 1.2 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Perennial Mid-Stature Cool Season Grasses | 45–179 | ||||

| Indian ricegrass | ACHY | Achnatherum hymenoides | 45–90 | 10–20 | ||

| squirreltail | ELELE | Elymus elymoides ssp. elymoides | 22–67 | 5–15 | ||

| needle and thread | HECO26 | Hesperostipa comata | 4–45 | 1–10 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 0–45 | 0–10 | ||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 0–45 | 0–10 | ||

| Montana wheatgrass | ELAL7 | Elymus albicans | 0–45 | 0–10 | ||

| 2 | Rhizomatous Grasses | 22–45 | ||||

| thickspike wheatgrass | ELLAL | Elymus lanceolatus ssp. lanceolatus | 22–45 | 5–10 | ||

| 3 | Misc. Grasses/Grasslikes | 22–45 | ||||

| plains reedgrass | CAMO | Calamagrostis montanensis | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| needleleaf sedge | CADU6 | Carex duriuscula | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| threadleaf sedge | CAFI | Carex filifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| Grass, perennial | 2GP | Grass, perennial | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 4 | Perennial Forbs | 22–40 | ||||

| rosy pussytoes | ANRO2 | Antennaria rosea | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Forb, perennial | 2FP | Forb, perennial | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Indian paintbrush | CASTI2 | Castilleja | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| pale bastard toadflax | COUMP | Comandra umbellata ssp. pallida | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| tapertip hawksbeard | CRAC2 | Crepis acuminata | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| larkspur | DELPH | Delphinium | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| fleabane | ERIGE2 | Erigeron | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| buckwheat | ERIOG | Eriogonum | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| beardtongue | PENST | Penstemon | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| spiny phlox | PHHO | Phlox hoodii | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| longleaf phlox | PHLOL2 | Phlox longifolia ssp. longifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| desertparsley | LOMAT | Lomatium | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| hoary tansyaster | MACA2 | Machaeranthera canescens | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| scarlet globemallow | SPCO | Sphaeralcea coccinea | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| stemless mock goldenweed | STAC | Stenotus acaulis | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| hollyleaf clover | TRGY | Trifolium gymnocarpon | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| clover | TRIFO | Trifolium | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| deathcamas | ZIGAD | Zigadenus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| evening primrose | OENOT | Oenothera | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| bladderpod | LESQU | Lesquerella | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| twinpod | PHYSA2 | Physaria | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| Townsend daisy | TOWNS | Townsendia | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| springparsley | CYMOP2 | Cymopterus | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| sego lily | CANU3 | Calochortus nuttallii | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| draba | DRABA | Draba | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| flaxleaf plainsmustard | SCLI | Schoenocrambe linifolia | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| rayless tansyaster | MAGR2 | Machaeranthera grindelioides | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| 5 | Annual Forbs | 0–4 | ||||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| rockjasmine | ANDRO3 | Androsace | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| bushy bird's beak | CORA5 | Cordylanthus ramosus | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 6 | Shrubs | 54–112 | ||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush | ARTRW8 | Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis | 54–112 | 10–20 | ||

| 7 | Misc Shrubs | 31–67 | ||||

| shadscale saltbush | ATCO | Atriplex confertifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Gardner's saltbush | ATGA | Atriplex gardneri | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| winterfat | KRLA2 | Krascheninnikovia lanata | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| granite prickly phlox | LIPU11 | Linanthus pungens | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| bud sagebrush | PIDE4 | Picrothamnus desertorum | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| greasewood | SAVE4 | Sarcobatus vermiculatus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| spineless horsebrush | TECA2 | Tetradymia canescens | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| shortspine horsebrush | TESP2 | Tetradymia spinosa | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| spiny hopsage | GRSP | Grayia spinosa | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| plains pricklypear | OPPO | Opuntia polyacantha | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| Shrub (>.5m) | 2SHRUB | Shrub (>.5m) | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

Table 17. Community 1.3 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Perennial Mid-Stature Cool Season Grasses | 94–179 | ||||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 0–157 | 0–35 | ||

| Indian ricegrass | ACHY | Achnatherum hymenoides | 67–135 | 15–30 | ||

| squirreltail | ELELE | Elymus elymoides ssp. elymoides | 22–67 | 5–15 | ||

| needle and thread | HECO26 | Hesperostipa comata | 4–45 | 1–10 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 0–45 | 0–10 | ||

| Montana wheatgrass | ELAL7 | Elymus albicans | 0–45 | 0–10 | ||

| 2 | Rhizomatous Grasses | 22–45 | ||||

| thickspike wheatgrass | ELLAL | Elymus lanceolatus ssp. lanceolatus | 22–45 | 5–10 | ||

| 3 | Misc Grasses/Grasslikes | 36–67 | ||||

| plains reedgrass | CAMO | Calamagrostis montanensis | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| needleleaf sedge | CADU6 | Carex duriuscula | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| threadleaf sedge | CAFI | Carex filifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| Grass, perennial | 2GP | Grass, perennial | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 4 | Perennial Forbs | 22–40 | ||||

| rosy pussytoes | ANRO2 | Antennaria rosea | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| scarlet globemallow | SPCO | Sphaeralcea coccinea | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| fleabane | ERIGE2 | Erigeron | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| desertparsley | LOMAT | Lomatium | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| hoary tansyaster | MACA2 | Machaeranthera canescens | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| beardtongue | PENST | Penstemon | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| spiny phlox | PHHO | Phlox hoodii | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| longleaf phlox | PHLOL2 | Phlox longifolia ssp. longifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| flaxleaf plainsmustard | SCLI | Schoenocrambe linifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| stemless mock goldenweed | STAC | Stenotus acaulis | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| hollyleaf clover | TRGY | Trifolium gymnocarpon | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| clover | TRIFO | Trifolium | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| deathcamas | ZIGAD | Zigadenus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Forb, perennial | 2FP | Forb, perennial | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| larkspur | DELPH | Delphinium | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Indian paintbrush | CASTI2 | Castilleja | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| pale bastard toadflax | COUMP | Comandra umbellata ssp. pallida | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| tapertip hawksbeard | CRAC2 | Crepis acuminata | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| buckwheat | ERIOG | Eriogonum | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| evening primrose | OENOT | Oenothera | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| twinpod | PHYSA2 | Physaria | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| bladderpod | LESQU | Lesquerella | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| springparsley | CYMOP2 | Cymopterus | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| Townsend daisy | TOWNS | Townsendia | 0–13 | 0–3 | ||

| sego lily | CANU3 | Calochortus nuttallii | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| draba | DRABA | Draba | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| rayless tansyaster | MAGR2 | Machaeranthera grindelioides | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| 5 | Annual Forb | 0–4 | ||||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| bushy bird's beak | CORA5 | Cordylanthus ramosus | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| rockjasmine | ANDRO3 | Androsace | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 6 | Shrubs | 22–45 | ||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush | ARTRW8 | Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis | 22–45 | 1–10 | ||

| 7 | Misc Shrubs | 36–67 | ||||

| shadscale saltbush | ATCO | Atriplex confertifolia | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| Gardner's saltbush | ATGA | Atriplex gardneri | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| spiny hopsage | GRSP | Grayia spinosa | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| winterfat | KRLA2 | Krascheninnikovia lanata | 4–22 | 1–5 | ||

| granite prickly phlox | LIPU11 | Linanthus pungens | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| bud sagebrush | PIDE4 | Picrothamnus desertorum | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| greasewood | SAVE4 | Sarcobatus vermiculatus | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| spineless horsebrush | TECA2 | Tetradymia canescens | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| shortspine horsebrush | TESP2 | Tetradymia spinosa | 0–22 | 0–5 | ||

| plains pricklypear | OPPO | Opuntia polyacantha | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

| Shrub (>.5m) | 2SHRUB | Shrub (>.5m) | 0–4 | 0–1 | ||

Table 18. Community 2.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Perennial Mid-Stature Cool Season Grasses | 17–34 | ||||

| Indian ricegrass | ACHY | Achnatherum hymenoides | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| Montana wheatgrass | ELAL7 | Elymus albicans | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| squirreltail | ELELE | Elymus elymoides ssp. elymoides | 3–17 | 1–5 | ||

| needle and thread | HECO26 | Hesperostipa comata | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| bluebunch wheatgrass | PSSP6 | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| 2 | Rhizomatous Grasses | 27–50 | ||||

| thickspike wheatgrass | ELLAL | Elymus lanceolatus ssp. lanceolatus | 27–50 | 10–15 | ||

| 3 | Misc Grasses/Grasslikes | 27–50 | ||||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 17–50 | 5–15 | ||

| Grass, perennial | 2GP | Grass, perennial | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| plains reedgrass | CAMO | Calamagrostis montanensis | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| needleleaf sedge | CADU6 | Carex duriuscula | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| threadleaf sedge | CAFI | Carex filifolia | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 4 | Perennial Forbs | 17–30 | ||||

| rosy pussytoes | ANRO2 | Antennaria rosea | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| Indian paintbrush | CASTI2 | Castilleja | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| pale bastard toadflax | COUMP | Comandra umbellata ssp. pallida | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| tapertip hawksbeard | CRAC2 | Crepis acuminata | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| Forb, perennial | 2FP | Forb, perennial | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| larkspur | DELPH | Delphinium | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| fleabane | ERIGE2 | Erigeron | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| buckwheat | ERIOG | Eriogonum | 3–17 | 1–5 | ||

| desertparsley | LOMAT | Lomatium | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| hoary tansyaster | MACA2 | Machaeranthera canescens | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| beardtongue | PENST | Penstemon | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| spiny phlox | PHHO | Phlox hoodii | 3–17 | 1–5 | ||

| longleaf phlox | PHLOL2 | Phlox longifolia ssp. longifolia | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| scarlet globemallow | SPCO | Sphaeralcea coccinea | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| stemless mock goldenweed | STAC | Stenotus acaulis | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| hollyleaf clover | TRGY | Trifolium gymnocarpon | 3–17 | 1–5 | ||

| clover | TRIFO | Trifolium | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| deathcamas | ZIGAD | Zigadenus | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| Townsend daisy | TOWNS | Townsendia | 0–10 | 0–3 | ||

| twinpod | PHYSA2 | Physaria | 0–10 | 0–3 | ||

| bladderpod | LESQU | Lesquerella | 0–10 | 0–3 | ||

| evening primrose | OENOT | Oenothera | 0–10 | 0–3 | ||

| springparsley | CYMOP2 | Cymopterus | 0–10 | 0–3 | ||

| sego lily | CANU3 | Calochortus nuttallii | 0–3 | 0–1 | ||

| rayless tansyaster | MAGR2 | Machaeranthera grindelioides | 0–3 | 0–1 | ||

| draba | DRABA | Draba | 0–3 | 0–1 | ||

| flaxleaf plainsmustard | SCLI | Schoenocrambe linifolia | 0–3 | 0–1 | ||

| 5 | Annual Forbs | 0–3 | ||||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 0–3 | 0–1 | ||

| rockjasmine | ANDRO3 | Androsace | 0–3 | 0–1 | ||

| bushy bird's beak | CORA5 | Cordylanthus ramosus | 0–3 | 0–1 | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 6 | Shrubs | 71–135 | ||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush | ARTRW8 | Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis | 71–135 | 20–30 | ||

| 7 | Misc Shrubs | 17–34 | ||||

| shadscale saltbush | ATCO | Atriplex confertifolia | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| Gardner's saltbush | ATGA | Atriplex gardneri | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 3–17 | 1–5 | ||

| spiny hopsage | GRSP | Grayia spinosa | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| winterfat | KRLA2 | Krascheninnikovia lanata | 3–17 | 1–5 | ||

| granite prickly phlox | LIPU11 | Linanthus pungens | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| bud sagebrush | PIDE4 | Picrothamnus desertorum | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| greasewood | SAVE4 | Sarcobatus vermiculatus | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| spineless horsebrush | TECA2 | Tetradymia canescens | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| shortspine horsebrush | TESP2 | Tetradymia spinosa | 0–17 | 0–5 | ||

| Shrub (>.5m) | 2SHRUB | Shrub (>.5m) | 0–3 | 0–1 | ||

| plains pricklypear | OPPO | Opuntia polyacantha | 0–3 | 0–1 | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

The following table lists suggested initial stocking rates for cattle under continuous season-long grazing under normal growing conditions. These are conservative estimates that should be used only as guidelines in the initial stages of the conservation planning process. Often, the current plant composition does not entirely match any particular plant community (as described in this ecological site description). Because of this, a field visit is recommended, in all cases, to document plant composition and production. More precise carrying capacity estimates should be calculated using field information along with animal preference data, particularly when grazers other than cattle are involved. Under more intensive grazing management, improved harvest efficiencies can result in an increased carrying capacity, but recovery time for upland sites is much longer than in a low intensity system.

If distribution problems occur, stocking rates must be reduced or facilitating conservation practices (i.e. cross-fencing, water development) used to maintain plant health and vigor.

Plant Community Production Carrying Capacity*

(lb./ac) Low-RV-High (AUM/AC) (AC/AUM)

Big Sagebrush/Bunchgrass (Reference) 200-400-500 0.06 17

Bunchgrass/Big Sagebrush 200-400-500 0.08 13

Bunchgrass 200-400-500 0.1 10

Big Sagebrush/Thickspike Wheatgrass 100-300-400 0.03 33

Thickspike Wheatgrass/Big Sagebrush 100-300-400 0.05 20

Big Sagebrush/Bare Ground 100-300-400 0.01 100