Ecological dynamics

It is impossible to determine in any quantitative detail the Reference Plant Community for this ecological site because of the lack of direct historical documentation preceding all human influence. In some areas, the earliest reports of dominant plants include the cadastral survey conducted by the General Land Office, which began in the late 19th century for this area (Galatowitsch 1990). However, up to the 1870s the Shoshone Indians, prevalent in northern Utah and neighboring states, grazed horses and set fires to alter the vegetation for their needs (Parson 1996). In the 1860s, Europeans brought cattle and horses to the area grazing large numbers of them on unfenced parcels year-long (Parson 1996). Itinerant and local sheep flocks followed as the proportion of browse increased.

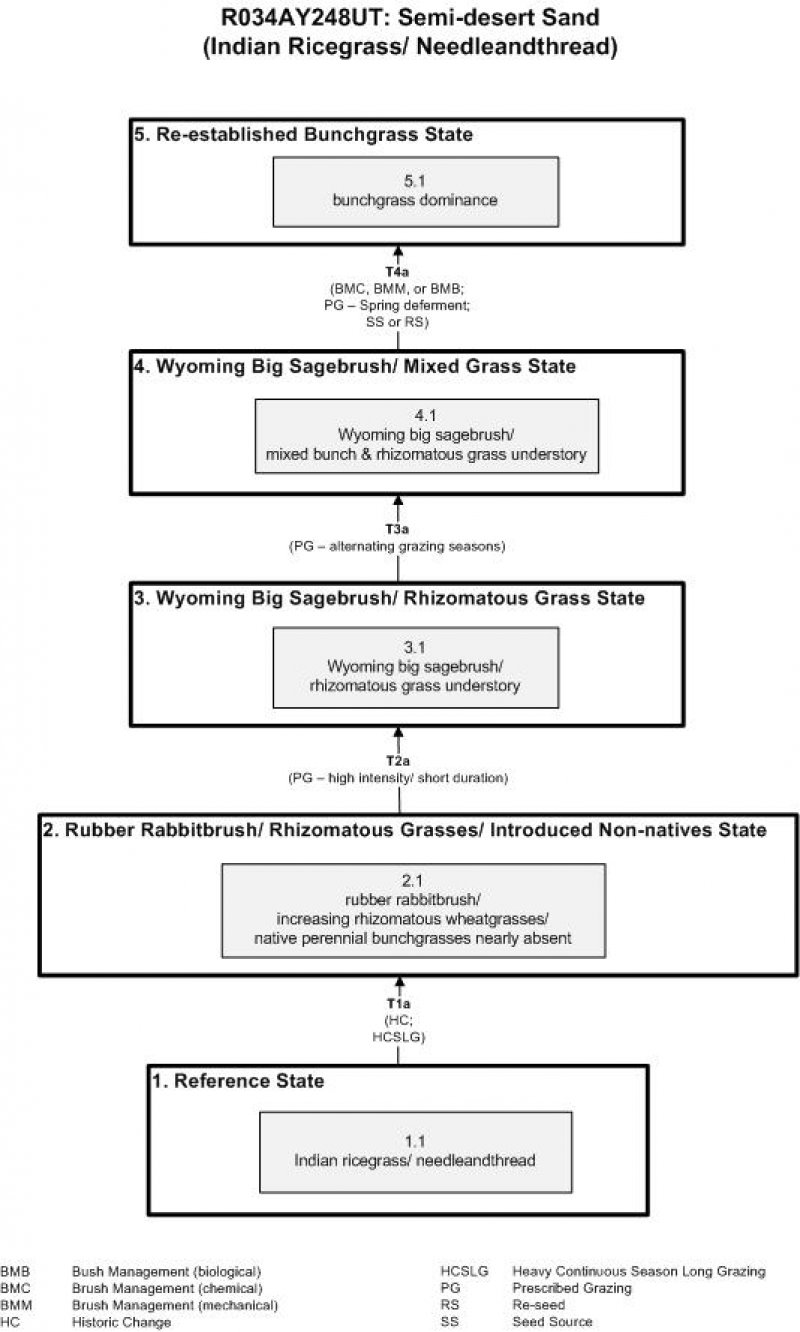

Below is a State and Transition Model diagram that illustrates the “phases” (common plant communities), and “states” (aggregations of those plant communities) that can occur on the site. Differences between phases and states depend primarily upon observations of a range of disturbance histories in areas where this ESD is represented. These situations include grazing gradients to water sources, fence-line contrasts, patches with differing dates of fire, herbicide treatment, tillage, etc. Reference State 1 illustrates the common plant communities that probably existed just prior to European settlement.

The major successional pathways within states, (“community pathways”) are indicated by arrows between phases. “Transitions” are indicated by arrows between states. The drivers of these changes are indicated in codes decipherable by referring to the legend at the bottom of the page and by reading the detailed narratives that follow the diagram. The transition between Reference State 1 and State 2 is considered irreversible because of the naturalization of exotic species of both flora and fauna, possible extinction of native species, and climate change. There may have also been accelerated soil erosion.

When available, monitoring data (of various types) were employed to validate more subjective inferences made in this diagram. See the complete files in the office of the State Range Conservationist for more details.

The plant communities shown in this State and Transition Model may not represent every possibility, but are probably the most prevalent and recurring plant communities. As more monitoring data are collected, some phases or states may be revised, removed, and new ones may be added. None of these plant communities should necessarily be thought of as “Desired Plant Communities.” According to the USDA NRCS National Range & Pasture Handbook (USDA-NRCS 2003), Desired Plant Communities (DPC’s) will be determined by the decision-makers and will meet minimum quality criteria established by the NRCS. The main purpose for including descriptions of a plant community is to capture the current knowledge at the time of this revision.

State 1

Reference

The Reference State is a description of this ecological site immediately prior to Euro-American settlement but long after the arrival of Native Americans. The description of the Reference State was determined by NRCS Soil Survey Type Site Location information and familiarity with rangeland relict areas where they exist. Prior to the coming of European livestock in the 1840s, an Indian ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides) and needle and thread (Hesperostipa comata) dominated community (1.1) probably occurred in southern Rich County where sands were blown in from adjacent pluvial plains of Ice Age streams flowing from the western Uinta Mountains. A more complete list of species by lifeform for the Reference State is available in the accompanying tables in the “Plant Community Composition by Weight and Percentage” section of this document.

Community 1.1

Indian ricegrass/ Needle and thread

Community Phase 1.1: Indian ricegrass/ Needle and thread

This plant community would have been characterized by primarily Indian ricegrass and needle and thread bunchgrasses.

State 2

Rubber Rabbitbrush/ Rhizomatous Grasses/ Introduced Non-natives

State 2 is a description of the ecological site shortly following Euro-American settlement, and is considered the current potential for this site. This was once a grassland where native perennial bunchgrasses were nearly grazed out due to the heavy sustained use from trail-connected livestock beginning in the early 1840s. Shrubs and grasses more tolerant of these impacts proliferated. Subsequently rubber rabbitbrush and slender wheatgrass grew to dominate the site, while what native perennial bunchgrasses remained were extremely scarce (2.1). A small component of non-native species, such as cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) and bulbous bluegrass (Poa bulbosa), have now been introduced to these sites. Continued heavy livestock grazing reduces state resiliency. Alternatively, reducing livestock use will maintain state resiliency.

Community 2.1

Rubber Rabbitbrush/ Increasing Rhizomatous Wheatgrasses/ Native Perennial Bunchgrasses Nearly Absent

Community Phase 2.1: Rubber Rabbitbrush/ Increasing Rhizomatous Wheatgrasses/ Native Perennial Bunchgrasses Nearly Absent

This plant community is dominated rubber rabbitbrush with a slender wheatgrass understory. Indian ricegrass and needle and thread are only a minor component or absent, and a small component of non-native annual grasses may be present.

State 3

Wyoming Big Sagebrush/ Rhizomatous Grass

This is a brush dominated community with an understory of mostly grazing-tolerant rhizomatous grasses such as slender wheatgrass. Continued heavy livestock grazing will reduce state resiliency, while reduction of livestock grazing maintains state resiliency.

Community 3.1

Wyoming Big sagebrush/ Rhizomatous grass understory

Community Phase 3.1: Wyoming Big sagebrush/ Rhizomatous grass understory

This community is characterized by Wyoming big sagebrush with a rhizomatous grass understory, composed primarily of slender wheatgrass.

State 4

Wyoming Big Sagebrush/ Mixed Grass

This state is dominated by Wyoming big sagebrush with mix of caespitose and rhizomatous grasses (e.g. slender wheatgrass, Indian ricegrass, and needle and thread) and less palatable forbs deathcamas (Zigadenus spp.).

Community 4.1

Wyoming Big sagebrush/ Mixed bunch & rhizomatous grass understory

Community Phase 4.1: Wyoming Big sagebrush/ Mixed bunch & rhizomatous grass understory

Wyoming big sagebrush dominated with mix of caespitose and rhizomatous grasses and forbs.

State 5

Re-established Bunchgrass

This re-established bunchgrass-dominated state will have relatively lower species richness and productivity than the grasslands that existed previously on these sites. However, the primary species of Indian ricegrass, needleandthread, and bottlebrush squirreltail will likely be present provided the necessary seed source and no accelerated soil erosion has taken place. Additionally, the inevitable occurrence of a few exotic species and loss of the native perennial forbs will prevent a restoration to pre-settlement conditions. Continued high intensity, short duration grazing rotated between seasons maintains state resiliency of this state. A return to heavy growing season use every year will reduce state resiliency.

Community 5.1

Bunchgrass dominance

Community Phase 5.1: Bunchgrass dominance

This is a return to a proxy of the grassland of the reference state, although it will differ in its species composition, and productivity will be lower because of reduction in soil nutrient pools.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Transition T1a: from State 1 to State 2 (Reference State to Rubber Rabbitbrush/ Rhizomatous Grasses/ Introduced Non-natives State)

The simultaneous introduction of exotic species, both plants and animals, and possible extinctions of native flora and fauna, along with climate change, causes State 1 to transition to State 2. Additionally, these sites were particularly favored by trail-connected livestock from the early 1840s onward. Thus, by the time of the GLO survey and through Stoddart’s (1940) evaluation, much of the native perennial bunchgrasses were lost. Sites were quickly invaded by rubber rabbitbrush (Ericameria nauseosa) and the more grazing tolerant rhizomatous grasses, such as slender wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus). Reversal of these historic changes (i.e. a return pathway) back to State 1 is not practical.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Transition T2a: from State 2 to State 3 (Rubber Rabbitbrush/ Rhizomatous Grasses/ Introduced Non-natives State to Wyoming Big Sagebrush/ Rhizomatous Grass State)

With further diminishment of grazing pressure and a switch from season-long to high intensity short duration grazing from the 1970s onward, much of the rubber rabbitbrush has been replaced by Wyoming big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis). A key indicator of the approach to this transition is the change in species composition. A reduction in lengths of time over which livestock grazing takes place will trigger the transition.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Transition T3a: from State 3 to State 4 (Wyoming Big Sagebrush/ Rhizomatous Grass State to Wyoming Big Sagebrush/ Mixed Grass State)

With grazing use currently alternating between seasons, and high intensity/ short duration grazing patterns, we can expect some recovery of the bunchgrasses. However, decades of season-long sheep use greatly diminished the native perennial forbs that were previously present. A key indicator of the approach to transition is an increase in bunchgrass cover. A diminishment of heavy growing-season utilization will trigger the transition. Continued heavy growing-season livestock utilization of grasses will reduce state resiliency.

Reduction of growing-season utilization of bunchgrass will maintain state resiliency.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 5

Transition T4a: from State 4 to State 5 (Wyoming Big Sagebrush/ Mixed Grass State to Re-established Bunchgrass State)

With mechanical, chemical, or biological (e.g. sheep use in fall season) shrub control of the sagebrush, followed by grazing deferment during the spring growth period of the bunch grasses, and provided adequate seed source, it might be possible to bring back the bunchgrasses, such as Indian ricegrass and needle and thread, to eventually dominate again. A key indicator of the approach to this transition is a change in species composition. Changes in the intensity and seasons of livestock use will trigger this transition.