Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F043AX957MT

Lower Subalpine Frigid Coniferous western redcedar (Thuja plicata)-western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla)

Last updated: 5/06/2024

Accessed: 01/07/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 043A–Northern Rocky Mountains

This MLRA is located in Montana (43 percent), Idaho (34 percent), and Washington (23 percent). It makes up about 31,435 square miles (81,460 square kilometers). It has no large cities or towns. It has many national forests, including the Okanogan, Colville, Kootenai, Lolo, Flathead, Coeur d’Alene, St. Joe, Clearwater, and Kaniksu National Forests.

This MLRA is in the Northern Rocky Mountains Province of the Rocky Mountain System. It is characterized by rugged, glaciated mountains; thrust- and block-faulted mountains; and hills and valleys. Steep-gradient rivers have cut deep canyons. Natural and manmade lakes are common.

The major Hydrologic Unit Areas (identified by four-digit numbers) that make up this MLRA are: Kootenai-Pend Oreille-Spokane (1701), 67 percent; Upper Columbia (1702), 18 percent; and Lower Snake (1706), 15 percent. Numerous rivers originate in or flow through this area, including, the Sanpoil, Columbia, Pend Oreille, Kootenai, St. Joe, Thompson, and Flathead Rivers.

This area is underlain primarily by stacked slabs of layered sedimentary or metasedimentary bedrock. The bedrock formations range from Precambrian to Cretaceous in age. The rocks consist of shale, sandstone, siltstone, limestone, argillite, quartzite, gneiss, schist, dolomite, basalt, and granite. The formations have been faulted and stacked into a series of imbricate slabs by regional tectonic activity. Pleistocene glaciers carved a rugged landscape that includes sculpted hills and narrow valleys filled with till and outwash. Continental glaciation over road the landscape in the northern half of the MLRA while glaciation in the southern half was confined to montane settings.

The average annual precipitation is 25 to 60 inches (635 to 1,525 millimeters) in most of this area, but it is as much as 113 inches (2,870 millimeters) in the mountains and is 10 to 15 inches (255 to 380 millimeters) in the western part of the area. Summers are dry. Most of the precipitation during fall, winter, and spring is snow. The average annual temperature is 32 to 51 degrees F (0 to 11 degrees C) in most of the area, decreasing with elevation. In most of the area, the freeze-free period averages 140 days and ranges from 65 to 215 days. It is longest in the low valleys of Washington, and it decreases in length with elevation. Freezing temperatures occur every month of the year on high mountains, and some peaks have a continuous cover of snow and ice.

The dominant soil orders in this MLRA are Andisols, Inceptisols, and Alfisols. Many of the soils are influenced by Mount Mazama ash deposits. The soils in the area have a frigid or cryic soil temperature regime; have an ustic, xeric, or udic soil moisture regime; and dominantly have mixed mineralogy. They are shallow to very deep, are very poorly drained to well drained, and have most of the soil texture classes. The soils at the lower elevations include Udivitrands, Vitrixerands and Haplustalfs. The soils at the higher elevations include Dystrocryepts, Eutrocryepts, Vitricryands , and Haplocryalfs. Cryorthents, Cryepts, and areas of rock outcrop are on ridges and peaks above timberline

This area is in the northern part of the Northern Rocky Mountains. Grand fir, Douglas-fir, western red cedar, western hemlock, western larch, lodgepole pine, subalpine fir, ponderosa pine, whitebark pine, and western white pine are the dominant overstory species, depending on precipitation, temperature, elevation, and landform aspect. The understory vegetation varies, also depending on climatic and landform factors. Some of the major wildlife species in this area are whitetailed deer, mule deer, elk, moose, black bear, grizzly bear, coyote, fox, and grouse. Fish, mostly in the trout and salmon families, are abundant in streams, rivers, and lakes.

More than one-half of this area is federally owned and administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Much of the privately-owned land is controlled by large commercial timber companies. The forested areas are used for wildlife habitat, recreation, watershed, livestock grazing, and timber production. Meadows provide summer grazing for livestock and big game animals. Less than 3 percent of the area is cropland.

LRU notes

This ecological site resides in MLRA 43A in the Livingston-Lewis-Apgar Mountains which includes the bulk of Glacier National Park (GNP) and the lower western valley portions along the Flathead River. The landscape is mountains and landforms include glaciated mountains with associated features such as U-shaped valleys, mountain slopes, alpine ridges, cirques, valley floors and moraines. Glaciation of this area was in the form of alpine, icecaps and valley outlet glaciers. It also includes associated alluvium and outwash features. This area includes low valleys to tall mountains with elevation ranging 989-2,762 m (3,250-9,050 ft.). The climate is cold and wet with mean annual air temperature of 3 degrees Celsius (37 degrees F)., mean frost free days of 65 days and mean annual precipitation of 1,295 mm (51 in.) and relative effective annual precipitation is 169 cm (66 in.). The soil temperature regime is cryic and the soil moisture regime is udic. The geology of this area is dominated by metasedimentary rocks of the Belt Supergroup (Grinnell argillite and Siyeh limestone) with minor Tertiary sediments. Soils are generally weakly developed on mountain slopes within U-shaped valleys. Parent materials are commonly of colluvium, till, and residuum from metasedimentary rocks. Limestone bedrock within this part of the Belt Supergroup is not highly calcareous and due to high precipitation received in this area most carbonates at mid and upper elevations have been leached from the soil profiles. Bedrock depth varies greatly with location, landform and slope position. Volcanic ash is often found in the soil surface with various degrees of mixing. Thicker volcanic ash can be found on more stable positions on mid and upper elevation slopes that are protected from wind erosion. Volcanic ash is not typically found in low elevation areas on stream and outwash terraces associated with streams and rivers. There are numerous large lakes including St. Mary, Bowman, Kintla, Lake Sherburne, Logging, Upper Waterton and numerous creeks (

Classification relationships

This ecological site relates to the USFS Habitat Type THSE/CLUN2 & THPL/CLUN2. This site relates to the USFS Habitat Type Group 5 and Fire Group 11. Both of these classification guides are specifically for the western Montana and northern Idaho region.

This ecological site relates to the National Park Service, NatureServe classification, Thuja plicata/Clintonia uniflora Forest (CEGL000474)

Ecological site concept

Ecological Site Concept

The lower subalpine frigid coniferous site is found west of the Continental Divide in moist areas within this maritime climate in glacial valley wall and lateral moraine landforms on back and foot slope positions, and on all aspects, spanning elevations from 1,000 to 1,500 meters (3,280-4,920 feet). The Reference Community is dominated by western cedar and western hemlock, with early seral tree species constrained to less than 3% of the overstory canopy. The ground cover consists predominantly of duff (63%) with high cover of moss (29%), and low cover of embedded litter (5%) and trace stones. The vegetation structure is that of very tall trees from 42-92 feet tall of western larch, western redcedar and western hemlock. The understory is multistoried though fairly sparse. The tallest understory layer is 51-102 cm or 20-40 inches tall and can include common ladyfern (Athyrium filix-femina), common snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus), white spirea (Spiraea betulifolia), and thinleaf huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum). The lowest layer is less than 25 cm or 10 inches tall and can include fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata), queencup beadlily (Clintonia uniflora), western rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia), twinflower (Linnaea borealis), threeleaf foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata), and Oregon boxleaf (Paxistima myrsinites). The most common seral tree species is western larch. The understory is depauperate of species and cover is very low. Species are shade-loving and include princes plume, queencup beadlily, western rattlesnake plantain, and twinflower with a thick cover of moss. Soils associated with this ecological site are very deep ash-capped soils over rocky subsoils. Ash thickness on these soils varies from 20cm to 50+ cm and provides a boost in water-holding capacity to these sites. These soils generally belong in the Andic Eutrudept soil subgroup, but also in the Typic Hapludands and Andic Dystrudepts. Diagnostic features include an ochric epipedon, andic soil properties and a cambic horizon. There is a thin organic layer present in these soils, generally less than 5 cm thick.

Associated sites

| F043AX952MT |

Lower Subalpine Cool Moist Coniferous subalpine fir-Engelmann spruce/Rocky Mountain maple-thinleaf huckleberry/thimbleberry The 43A Lower Subalpine Frigid Coniferous ecological site is associated with the 43A Subalpine Coniferous Cool Moist Ashy Very Deep ecological site. The 43A Lower Subalpine Coniferous Cool Moist Ashy Very Deep is found in cool, moister mid-elevations that span the lower subalpine to subalpine. This ecological site is found on back, foot and toeslope positions, on glacial valley wall and moraine landforms, on all slopes, at elevations ranging 1,000 to 2,100 meters (3,280-6,890 feet). The 43A Lower Subalpine Frigid Coniferous ecological site is associated with the 43A Subalpine Coniferous Cool Moist Ashy Very Deep ecological site. The 43A Lower Subalpine Coniferous Cool Moist Ashy Very Deep has soils associated with this Ecological Site that are very deep, well drained or somewhat excessively drained and have subsoils with abundant rock fragments. The parent material is volcanic ash over glacial till from metasedimentary rock. In Soil Taxonomy, these soils classify primarily as Inceptisols soil order and more specifically as the Andic Haplocryepts taxonomic subgroup. The 43A Lower Subalpine Frigid Coniferous ecological site is associated with the 43A Subalpine Coniferous Cool Moist Ashy Very Deep ecological site. The 43A Lower Subalpine Coniferous Cool Moist Ashy Very Deep has a reference vegetation community of Subalpine fir-Engelmann spruce overstory and an understory of Rocky Mountain maple, thinleaf huckleberry, thimbleberry, wild Sarsaparilla, threeleaf foamflower and queencup bead lily. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Thuja plicata |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Chimaphila umbellata |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Clintonia uniflora |

Physiographic features

The lower subalpine frigid coniferous site is found west of the Continental Divide in moist areas within this maritime climate in glacial valley wall and lateral moraine landforms on back and foot slope positions, and on all aspects, spanning elevations from 1,000 to 1,500 feet. In Montana, in general, the site is found at elevations ranging from 2,000-5,000 feet. The annual precipitation generally is above 32” (USFS H.T. Guide, 1977).

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Mountains

> Lateral moraine

(2) Mountains > Glacial-valley wall (3) Mountains > Alluvial fan (4) Mountains > Outwash terrace |

|---|---|

| Elevation | 1,000 – 1,500 m |

| Slope | 5 – 35% |

| Aspect | W, NW, N, NE, E, SE, S, SW |

Climatic features

This ecological site is found in the frigid soil temperature regime and the udic soil moisture regime. The soils that support this native plant community occur in the frigid soil temperature regime (average annual temperature less than 8 degrees C, with more than 5 degrees C summer-winter fluctuation). An udic soil moisture regime denotes that the rooting zone is usually moist throughout the winter and the majority of summer. This site is found on the west side of the Continental Divide and has more maritime weather influences.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 17-57 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 76-117 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 508-660 mm |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 6-68 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 66-127 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 508-711 mm |

| Frost-free period (average) | 37 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 97 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 584 mm |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 3. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) POLEBRIDGE 1 N [USC00246618], Essex, MT

-

(2) POLEBRIDGE [USC00246615], Essex, MT

-

(3) WEST GLACIER [USC00248809], Kalispell, MT

Influencing water features

This ecological site is not influenced by wetland or riparian water features but may be found on stream terraces or adjacent to wetland and riparian areas.

Soil features

Soils associated with this ecological site are very deep ash-capped soils over rocky subsoils. Ash thickness on these soils varies from 20cm to 50+ cm and provides a boost in water-holding capacity to these sites. These soils generally belong in the Andic Eutrudept soil subgroup, but also in the Typic Hapludands and Andic Dystrudepts. Diagnostic features include an ochric epipedon, andic soil properties and a cambic horizon. There is a thin organic layer present in these soils, generally less than 5 cm thick.

“Mount Mazama (Crater Lake, Oregon) violently erupted around 6,700 years ago. The massive plume of volcanic ash from the eruption drifted in a northwest direction through northwest Montana. Deposition was widespread throughout western Montana, but is greatest in the northwest corner of the state. The ash likely fell uniformly across the landscape and was then re-distributed by wind and water erosion. The resulting distribution, given the dominate winds from the south and southwest, favors thicker deposits of ash on slopes with north-facing aspects. Little ash is usually found on south-facing slopes except at the higher elevations in cirque basins.

Volcanic ash has a large impact on overstory and understory plant productivity due to the increase in water-holding capacity that it adds to the soil. The ash is typically found as a surface mantle overlying whatever existing soil or parent material it was deposited on top of. The ash mantles exhibit varying amounts of mixing with the underlying material, but tend to lack the rock fragments commonly found in the sub-soils of the park. Ashy soil layers generally tend to have brighter colors than the underlying sub-soils and have a soft and very friable consistency.” (J. Skovlin, personal communication, 2015). (Soil Survey Staff, 2015). For more information on soil taxonomy, please follow this link:

http://http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/survey/class/?cid=nrcs142p2_053580

CORRELATED SOIL SERIES & TAXONOMIC CLASS NAME

Backroad Loamy-skeletal, mixed, superactive, frigid Andic Dystrudepts

Pasturecreek Loamy-skeletal, isotic, frigid Andic Eutrudepts

Sunroad Coarse-loamy, isotic, frigid Andic Eutrudepts

Typic Hapludands Medial over sandy or sandy-skeletal, amorphic over isotic, frigid Typic Hapludands

Figure 7. Soils for this ecological site.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Till

–

metasedimentary rock

(2) Colluvium – metasedimentary rock (3) Alluvium – metasedimentary rock |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Gravelly, ashy loam (2) Ashy loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy-skeletal |

| Drainage class | Well drained to somewhat excessively drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate |

| Soil depth | 152 – 254 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (6.9-18.3cm) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (11.4-16.5cm) |

Not specified |

Ecological dynamics

Ecological Dynamics of the Site

This site is found west of the Continental Divide in moderately cool and moist mid-elevations sites. Within Glacier National Park (NP), this ecological site has its greatest expression on the eastern side of Lake McDonald. While primary data was collected in Glacier NP, this habitat type also spans into the adjacent US Forest Service (USFS) land Flathead National Forest (NF), and in the Kootenai NF.

Management

Various management strategies can be employed for this ecological site, depending upon the ownership of the particular land and which value is prioritized. The management of the forest determines the composition of the stand and the amount of fuel loading. A stand will be managed differently and look differently if it is managed for timber or ecological services like water quality and quantity, old growth, or endangered species. If a stand is managed for timber, then it may be missing certain attributes necessary for lynx habitat. If a stand is managed for lynx habitat, it may have increased fuels and therefore an increased risk of wildfires.

The USFS Habitat Type Guide (1973) states that the basal area on the western side of the Continental Divide for western hemlock/queencup beadlily is 267+/-55 ft2 per acre. The fifty-year site index for western white pine is 62, western larch is 80, spruce is 77, and grand fir is 50. Basal area for western redcedar/queencup beadlily is 305+/-96 ft2 per acre and the site index for Douglas-fir is 66, western larch is 63, PICEA is 72+/-14, grand fir is 61, and subalpine fir is 74.

Timber production on these sites is very high, particularly in the seral phases of this ecological site.

Each national forest has a specific management plan. The management plan for the Flathead N.F. also has an Appendix B that gives specific management guidelines for habitat types (which relate to our forested ecological sites) found on the forest in relation to current and historic data on forest conditions (Flathead N.F. Plan, 2001 and Appendix B). Another guiding USFS document is the Green et al. document (2005) which defines “Old Growth” forest for the northern Rocky Mountains. This document provides an ecologically-based classification of old growth based on forest stand attributes including numbers of large trees, snags, downed logs, structural canopy layers, canopy cover, age, and basal area. While this document finds that the bulk of the pre-settlement upland old growth in the northern Rockies was in the lower elevation, ground-fire maintained ponderosa pine/western larch/Douglas-fir types (Losensky, 1992), it does not mean that other types were not common or not important. This could apply to some of the areas of this ecological site.

State 1.0

Western White Pine (Pinus monticola)(Western redcedar (Thuja plicata)-Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla))/pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata)-queencup beadlily (Clintonia uniflora).

Historically western white pine would have been within Flathead County, which encompasses the Flathead N.F. and in lower elevations, west of the Continental Divide in Glacier NP. The historic extent of western white pine in Glacier National Park was primarily along the western border. Originally, western white pine covered five million acres in the Inland Northwest. Western white pine is incredibly productive for timber with a very high growth rate, tall and deep–rooted, and competes best on highly variable, high resource sites. As well, it is tolerant to the native root rot diseases and other native forest pests. Western white pine is susceptible to Armillaria root disease only when young, and to mountain pine beetle largely at advanced ages (over 140 years). It also has the capability to thrive in a wide variety of sites and environments, which means it has high ecological flexibility. It is a long-living seral species that tolerated intense timber harvesting practices and severe fire disturbance by its ability to regenerate heavily on mineral soil and full sunlight. Fire greatly influences the composition, structure, and function of vegetation across the landscape. Historically, it was mixed severity fire between severe stand replacement fires. Western larch and western white pine are long-lived, fire-adapted, shade-intolerant tree species that historically thrived. Also present in significant amounts particularly in young stands, but declined through time due to effects of insects and pathogens, were the shorter-lived, shade-intolerant, fire-adapted tree species such as Douglas-fir and lodgepole pine. Shade-tolerant, fire-intolerant tree species such as western cedar, western hemlock, grand fir, Engelmann spruce, and subalpine fir were present, but rarely survived long enough to dominate stands except in areas where the interval between fires was unusually long and where root disease was not severe.

Prior to the 20th century, western white pine was a major component in forested ecosystems of the inland northwest U.S. It has been greatly reduced in distribution and abundance by white pine blister rust, mountain pine beetles, and anthropogenic fire exclusion (Tomback and Achuff, 2010). Western white pine has been replaced by Douglas-fir, grand fir, and western hemlock. Douglas-fir and grand fir are susceptible to a greater variety of insect and disease problems and hemlock is more sensitive to drought and decay. More stands have also progressed to the climax species-dominated phase, which previously were rarely achieved due to the fire rotations and susceptibility of these species to disease and forest pests. In a study of pathogens and insects effects on forests within the Inland Empire found that, excluding fire, there were more than 90% of sample stands changed to a different cover type, structure stage, or both during a 40-year period that was coincident with the blister rust epidemic and fire suppression policy. Root pathogens, white pine blister rust, and bark beetle were the cause of most changes, and this accelerated succession of western white pine, ponderosa pine, and lodgepole pine to later successional, more shade-tolerant species. Structure was reduced in stand density or prevented canopy closure. Grand fir, Douglas-fir, and subalpine fir were the predominant cover types at the end of the period, and were highly susceptible to root diseases, bark beetles, fire, and drought. It is estimated that there will be continuation of this trend occurring in low-density mature stands and younger pole-sized stands that result from root disease and bark beetle-caused mortality (Byler and Hagel, 2000). These stands also are less productive in terms of timber. They are dominated by species with high nutrient demands, and therefore nutrient storage and cycling rates are increasingly depressed. This will likely lead to ever-increasing stress and destabilization by pests and diseases. Drought can further exacerbate the situation by stressing trees.

The Inland Empire Tree Improvement Cooperative and the USFS have a breeding program for blister-resistant western white pine. Approximately 5 percent of the original acre range was re-planted with rust-resistant stock. Currently, the modified stock shows about 60 percent resistance to blister rust. A study modeling the effects of climate change found that warming temperatures would favor increased abundance of western white pine over existing climax and shade-tolerant species in Glacier NP, mainly because warmer conditions potentiate fire dynamics, including increased wildfire frequency and extent, which facilitates regeneration (Loehman, et al., 2011).

State 2.0

Western redcedar (Thuja plicata)-Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla)/pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata)-queencup beadlily (Clintonia uniflora)-western rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia)-twinflower (Linnea borealis)/moss.

State 2 is different than State 1 in that western white pine no longer plays a significant role in the seral communities. It has been dramatically reduced in numbers and area by the epidemics of white pine blister rust and western spruce budworm, and by dramatic fire suppression. Therefore, climax species have been able to fill the seral role that western white pine once held. As well, more forests are progressing to the climax or Reference Phase than historically, when most forests were in the fire-maintained western white pine-dominated seral phase. State 2 forests are now dominated by the shade-tolerant climax species western redcedar and western hemlock. While there is a tremendous effort to bolster the numbers of western white pine, it currently covers only 5 percent of its historic range.

This ecological site is described as having moderately cool and moist site conditions. The Reference state is dominated by western redcedar and western hemlock, both of which are shade-tolerant climax conifers that grow in similar environments. Western redcedar has a larger geographic extent in Montana, but western hemlock usually is capable of attaining dominance over western redcedar and other species at climax because it is better able to reproduce under a dense forest canopy. Western redcedar is able to maintain itself indefinitely as a minor climax species because of its shade tolerance, longevity (often 600-1,000 years), and apparent ability to regenerate vegetatively (USFS H.T. Guide, 1973). Within Glacier NP, these species are co-dominant in nearly all of the sites visited. The seral successional stages have very diverse overstory tree composition and can be very productive in terms of basal area. Douglas-fir, western larch and, to a lesser extent, spruce are often dominants in seral stands with lodgepole, western white pine, and paper birch as minor components. Grand fir and subalpine fir can be either minor seral or climax components. Western redcedar and western hemlock will regenerate after disturbance along with seral species, and it will take centuries for these species to gain dominance in the overstory over the seral species. The early successional phase can be dominated by fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium). The understory in seral successional phases have moisture-loving forbs or shrubs including Scouler’s willow, thimbleberry, serviceberry, rocky mountain maple, thinleaf huckleberry, and snowbush ceanothus. The historic fire regime of these forests is one of low fire frequency, but fire severity can be highly variable. It can be low due to the most common moist conditions, but can be severe during times of drought. Fire return intervals range from 50 to greater than 200 years, but include mixed severity fires on 50-85 year intervals, as well as stand replacement fires on 150-250 year intervals. Western redcedar can thrive for centuries on this ecological site without disturbance. The Northern Rocky Mountain mesic montane mixed-conifer forest-cedar groves are in fire regime group 5 and had a fire interval of 334 years, with 87 percent of fires classified as of replacement severity and 13 percent of fires classed as mixed severity and none as low severity (USDA, USFS, FEIS, Fire Regime). Fuel loadings for this ecological site can be very high due to deadfall and natural thinning of small and medium-sized branches. In early and intermediate successional phases, the understory can have high cover adding to fuel loadings. Due to the generally moist conditions, fire return intervals can be long. In general, the variability in fire regime and the high diversity of tree species present in most stands, except the Reference, allow this ecological site to form a diverse mosaic landscape with varying dominance or mixes of seral species.

The general fire succession process is that after stand replacement fires, the community reverts to an herbaceous one, then to shrubland. If fire is reoccurring in this phase, then the phase is maintained for a long time. The herbaceous community can be dominated by the disturbance-loving fireweed, beargrass, or numerous other species, depending upon the seedbank at the site and beyond. Duration of the herbaceous or shrubland phase is also dependent upon the availability of tree seed. If serotinous lodgepole pine seeds are available, then the site will become dominated by it and a lodgepole pine stand will develop for about 10-25 years (Habeck, 1968). After that time, other species become established including western larch and other conifers. If serotinous lodgepole pine seeds are not present, then the seedlings are a very diverse mixture of conifers. These seedlings form a thick carpet on the site shared with shrub species such as Scouler’s willow, white spirea, thinleaf huckleberry, thimbleberry, and Oregon boxwood. Forbs present include ferns, beargrass and fireweed. Moss cover can be variable. If fire does not occur, the seedlings will grow to saplings and then pole-sized trees of diverse seral species. Low to moderate fires in this stage would favor fire-tolerant seral species over western redcedar, grand fir, or western hemlock, which are less fire-resistant. Severe fires will return these to the herbaceous or shrubland phase. In the pole-sized phase, seral species are abundant and western redcedar and western hemlock are just becoming established and usually have low cover (3-15 percent of the stand).Without further disturbance, this phase will continue to the maturing forest in which western redcedar and western hemlock become more evident in the stand and eventually have higher cover than the seral tree species. Western larch may survive severe fires in the maturing or mature phases. These trees would then provide seed for the stand initiation phase after a fire. As well, after frequent low to moderate fires in the mature phase, a relict western larch stand could occur. Reference stands in which only western redcedar and western hemlock occur can be rare, as seral species are long-lived and fire occurs frequently enough that stands seldom develop beyond the mature phase. Along the shores of Lake McDonald in Glacier NP, there were abundant stands that were in the Reference phase. The Robert fire in 2003 heavily impacted some areas on the west side of Lake McDonald, but other areas close to the shore were not affected. Reference stands may withstand low fires that thin the stand, but moderate or severe fires would return the site to the herbaceous or shrubland phase. Significant fires that have occurred on the west side of the Continental Divide that have affected this ecological site are the Robert Fire in 2003 that burned 54,191 acres, the Moose Fire in 2001 that burned 66,688 acres, and the Middle Fork Complex Fire in 2003 that burned 11,996 acres. There were historic fires within the area of this ecological site that burned significant portions in 1735 and another portion in 1926 (NPS Stand Age spatial layer).

Both western hemlock and western redcedar are subjected to a variety of diseases and insect pests including Armillaria root disease, Annosus root disease, pouch fungus, red belt fungus, pini rot, metallic wood borers, and roundheaded borers. Western redcedar also is susceptible to cedar laminated butt rot, cedar brown pocket rot, and cedar bark beetles. Western hemlock is also susceptible to Indian paint fungus.

A good tool to use to discern the levels of insects and diseases, the damage patterns, and whether these are at endemic or epidemic levels is aerial photography. These maps capture only moments in time, and infestations grow and move from location to location following their preferred habitat, so repeated photography can be necessary. Specifically for the northern region, the USFS Stand Health map shows, via many very large polygons throughout the area, that the major impact is defoliation by western spruce budworm. The defoliation was categorized as mostly of low severity (equal to or less than 50% defoliation) and some of high severity (with greater than 50% defoliation) on Abies species, and the damage is contiguous or nearly continuous. The forest type was categorized as W. Fir-Spruce. There also was defoliation by western spruce budworm on Douglas-fir, but to a much lesser degree. Larch casebearer, a defoliator of western larch, and generalized needlecast disease of western larch also was found, to a much lesser degree. Scattered small polygons showing damage were found throughout the region, including mortality from mountain pine beetle on lodgepole pines, Douglas-fir beetle on Douglas-fir, spruce beetle on Engelmann spruce, fir engravers and woolly adelgid on Abies species, and general Abies species mortality. These would affect the seral tree species of this ecological site and field notes corroborate these findings.

Community Phase 2.1: Reference

Western redcedar-western hemlock/prince’s plume-queencup beadlily-western rattlesnake plantain-twinflower/moss

Structure: Multistory with small gap dynamics

The Reference Community is dominated by western cedar and western hemlock, with seral tree species constrained to less than 3% of the overstory canopy. The ground cover consists predominantly of duff with fairly high cover of moss and trace cover of embedded litter and stones. The vegetation structure is that of very tall trees from 500-1,100 inches tall of western larch, western redcedar and western hemlock. The understory is multistoried though fairly sparse. Species occurring with the highest frequency of occurrence include thinleaf huckleberry, darkwoods violet, twinflower, western rattlesnake plantain, queencup beadlily and prince’s plume ( 15 sites of canopy cover data). Foliar cover at six sites indicate that the foliar cover is fairly high (50.8%) and the ground cover is primarily litter, which includes woody litter, litter or duff (total is 74%, duff is 63%) and moss (30%). The tallest understory layer is 20-40 inches tall and can include common ladyfern (Athyrium filix-femina), common snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus), white spirea (Spiraea betulifolia), and thinleaf huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum). The lowest layer is less than 10 inches tall and can include fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata), queencup beadlily (Clintonia uniflora), western rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia), twinflower (Linnaea borealis), threeleaf foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata), and Oregon boxleaf (Paxistima myrsinites). The most common seral tree species is western larch. The understory is depauperate of species and cover is very low. Species are shade-loving and include prince’s plume, queencup beadlily, western rattlesnake plantain, and twinflower with a thick cover of moss.

Community Phase Pathway 2.1A

This pathway represents a major stand-replacement fire disturbance such as a high-intensity fire, large scale wind event, or major insect infestation.

Forest overstory summarization table.

FOREST OVERSTORY

Forest canopy Canopy cover Average= 60%, Range= 45-90%

Average basal area Total 260-380 ft2/acre

Site Index at 100 yrs.: THPL (64-86); TSHE (65-91)

Community Phase 2.2: Stand Initiation. Regen: Lodgepole pine-western larch (mixed seral species)/

Scouler’s willow-white spirea-thinleaf huckleberry/thimbleberry-Oregon boxwood/fireweed-beargrass/moss.

Post- fire 1-5 years

Structure: Initially this post fire disturbance community is dominated by herbaceous and shrub species most commonly fireweed, species with a resident seedbank or disturbance loving species.

Structure: Continuous cover of regeneration-single story mixed tree species.

Post-fire 5-50 years

Structure: This is a forest in the stand initiation phase, possibly with scattered remnant mature trees; the composition of the seedlings depends on the natural seed sources available. Habeck found that in the vicinity of Lake Mcdonald in Glacier N.P., the dominant seral tree species is Lodgepole pine for 10-25 years post-fire. Afterwards, Western Larch will co-dominant from 25-50 years post-fire with other seral tree species at lower cover. Throughout the entire area of this ecological site, the regeneration will probably be a mixture. Overstory canopy cover is generally less than 10%, but the regeneration tree cover is very high forming a thick carpet. It is a mixture of species including: Lodgepole pine, Western larch, subalpine fir, Paper birch, Engelmann spruce, Western white pine, Black cottonwood, Quaking aspen, Douglas fir, Western redcedar and Western hemlock. The understory is a diverse mixture of herbaceous and shrub species including tall willow species, particularly Scouler’s willow, medium statured shrubs white spirea and thinleaf huckleberry, the low statured shrubs thimbleberry and Oregon boxwood. Herbaceous species include: fireweed, beargrass. Moss cover is variable.

Community Phase Pathway 2.2A

This pathway represents growth over time with no further significant disturbance. The areas of regeneration pass through the typical stand phases-competitive exclusion, maturation, understory reinitiating-until they resemble the old-growth structure of the reference community.

Community Phase 2.3: Intermediate Aged Forest.

Lodgepole pine-Douglas fir-Engelmann spruce-western larch-paper birch-subalpine fir-western white pine (western redcedar-western hemlock)/white spirea-snowberry-thinleaf huckleberry/thimbleberry/prince’s plume-queencup beadlily-twinflower-beargrass/moss.

This community phase is dominated by seral tree species that have matured to pole size and are in the competitive exclusion phase of forest succession. Overstory tree canopy is dense and competition for resources is very high. Canopy cover averages 50%. This community is incredibly diverse in tree species including: Lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, Engelmann spruce, Western larch, Paper birch, subalpine fir, Western white pine, Western redcedar and Western hemlock. The overstory canopy of Western redcedar and Western hemlock is less than 3% as they are just beginning to become established. The understory can have high cover of the medium sized shrubs white spirea, snowberry, Oregon boxleaf, common snowberry and thinleaf huckleberry. The short statured thimbleberry can have high cover. The herbaceous layer is diverse, with medium statured beargrass occurring frequently and sometime in high cover. Other herbaceous species include the short statured prince’s plume, queencup beadlily, trailplant and twinflower.

Figure 7. Plant Community 2.3 Intermediate Aged Forest, Dense Thick Pole Sized Trees.

Community Phase Pathway 2.3A

This pathway represents continued growth over time with no further major disturbance.

Community Phase Pathway 2.3B

This pathway represents a major stand-replacement fire disturbance such as a high-intensity fire, large scale wind event or major insect infestation.

Community Phase 2.4: Maturing Forest.

Western redcedar-western hemlock-subalpine fir-lodgepole pine-Engelmann spruce-western white pine/thinleaf huckleberry-snowberry-white spirea/wild sarsaparilla-heartleaf arnica-queencup beadlily-twinflower-beargrass/moss.

Structure:

This community is a maturing forest with vertical differentiation in the overstory tree canopy. Canopy cover averages

60%. This community has diverse tree species with Western redcedar and Western hemlock ranging 3-15% each and other seral tree species about equally distributed. These species include: Subalpine fir, Lodgepole pine, Engelmann spruce, Western white pine. The understory has patchy medium sized shrubs including: thinleaf huckleberry, snowberry, white spirea. There is a diverse understory of herbaceous species including: wild sarsaparilla, heartleaf arnica, queencup beadlily, twinflower and beargrass. There can be high cover of moss.

Community Phase Pathway 2.4A

This pathway represents continued growth over time with no further major disturbance.

Community Phase Pathway 2.4B

This pathway represents a major stand-replacement fire disturbance, such as a major insect outbreak, or major fire event which leads to the stand initiation phase of forest development.

Community Phase 2.5: Mature Forest.

Western redcedar-western hemlock (remnant seral species)/thinleaf huckleberry/threeleaf foamflower-prince’s plume-queencup beadlily-western rattlesnake plantain/moss.

Structure: Mature forest with vertical differentiation in the stand. Overstory is dominated by Western redcedar and Western hemlock although seral tree species are present and can have up to 15% cover each. Overstory canopy cover ranges 50-80%. Western larch is the most common seral species but others include: Grand fir, subalpine fir, Paper birch,

Lodgepole pine, Western white pine, and Douglas fir. The understory is diverse but generally has low overall cover. Thinleaf huckleberry occurs in clumps and queencup beadlily and western rattlesnake plantain are common.

Figure 9. Plant Community 2.5 Mature forest with some small gap dynamics, remnant seral tree species and western redcedar and western hemlock dominant.

Community Phase Pathway 2.5A

This pathway represents no further major disturbance. Continued growth over time, as well as ongoing mortality, leads to continued vertical diversification. The community begins to resemble the structure of the reference community, with small pockets of regeneration and a more diversified understory.

Community Phase Pathway 2.5B

This pathway represents a major stand-replacement fire disturbance leading to the stand initiation phase of forest development.

State 3.0

Another disease affecting this ecological site is root rot. While Douglas-fir, grand fir, and subalpine fir are most susceptible, western redcedar and western hemlock can be affected as well. Armillaria root disease is the most common root disease fungus in this region, and is especially prevalent west of the Continental Divide. It may be difficult to detect until it has killed enough trees to create large root disease pockets or centers, ranging in size from a fraction of an acre to hundreds of acres. The root disease spreads from an affected tree to its surrounding neighbors through root contact. The root disease effects the tree species most susceptible first, leaving less susceptible tree species that mask its presence. When root rot is severe, the pocket has abundant regeneration or dense brush growth in the center. Western redcedar is moderately resistant to Armillaria root rot in Idaho and Montana. The common disease expression is some mortality in saplings, and residuals of partial harvests often develop severe infections but are very slow to die (Hagle, 2010). There has been a link determined between parent material and susceptibility to root disease (Kimsey et al., 2012). Metasedimentary parent material is thought to increase the risk of root disease. Glacier National Park is dominated by metasedimentary parent material and may be more at risk than other areas to root disease (Kimsey et al., 2012). If a stand sustains very high levels of root disease mortality, then a coniferous stand could cross a threshold and become a shrubland, once all conifers are gone (Kimsey et al., 2012). Management tactics include to identify the type of Armillaria root disease, and manage for pines and larch. Pre-commercial thinning may improve growth and survival of pines and larch. Avoid harvests that leave susceptible species (usually Douglas-fir or true firs) as crop trees (Hagel, 2010).

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

Communities 1, 5 and 2 (additional pathways)

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Historical Reference State

Western white pine (western hemlock-western red cedar)/pipsissewa-Clintonia

Historically western white pine would have been within Flathead County, which encompasses the Flathead N.F. and in lower elevations, west of the Continental Divide in Glacier NP. The historic extent of western white pine in Glacier National Park was primarily along the western border. Originally, western white pine covered five million acres in the Inland Northwest. Western white pine is incredibly productive for timber with a very high growth rate, tall and deep–rooted, and competes best on highly variable, high resource sites. As well, it is tolerant to the native root rot diseases and other native forest pests. Western white pine is susceptible to Armillaria root disease only when young, and to mountain pine beetle largely at advanced ages (over 140 years). It also has the capability to thrive in a wide variety of sites and environments, which means it has high ecological flexibility. It is a long-living seral species that tolerated intense timber harvesting practices and severe fire disturbance by its ability to regenerate heavily on mineral soil and full sunlight. Fire greatly influences the composition, structure, and function of vegetation across the landscape. Historically, it was mixed severity fire between severe stand replacement fires. Western larch and western white pine are long-lived, fire-adapted, shade-intolerant tree species that historically thrived. Also present in significant amounts particularly in young stands, but declined through time due to effects of insects and pathogens, were the shorter-lived, shade-intolerant, fire-adapted tree species such as Douglas-fir and lodgepole pine. Shade-tolerant, fire-intolerant tree species such as western cedar, western hemlock, grand fir, Engelmann spruce, and subalpine fir were present, but rarely survived long enough to dominate stands except in areas where the interval between fires was unusually long and where root disease was not severe.

Community 1.1

Reference Community

Subalpine fir- Engelmann spruce overstory. Minor western white pine-western larch-grand fir

Reference phase of multi-storied forest canopy dominated by western redcedar and western hemlock.

Community 1.2

Western white pine-western larch- (lodgepole pine) seedlings

Post fire disturbance community of herb and shrub species.

Community 1.3

Western white pine-western larch-(subalpine fir-grand fir-Engelmann spruce)

Intermediate aged forest, dense thick pole sized trees.

Community 1.4

Western white pine- (western hemlock-western red cedar grand fir)

Maturing forest phase of seral tree species and western redcedar and western hemlock.

Community 1.5

Western white pine- (western hemlock-western red cedar-grand fir

Mature forest with some small gap dynamics, remnant seral trees species and western red cedar and western hemlock dominant.

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

A major stand-replacement disturbance, such as a major insect outbreak or major fire event, which leads to the stand initiation phase of forest development.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.3

Continued growth over time with no further major disturbance to dense single story pole sized stand.

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.4

Continued growth over time with no further major disturbance to mature stand with all size classes.

Pathway 1.3B

Community 1.3 to 1.5

Continued growth over time with no further major disturbance with patches of regeneration.

Pathway 1.4A

Community 1.4 to 1.1

Continued growth over time with no further major disturbance with patches of regeneration.

Pathway 1.5A

Community 1.5 to 1.1

Continued growth over time with no further major disturbance with patches of regeneration.

State 2

Current Potential State

Western redcedar (Thuja plicata)-Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla)/pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata)-queencup beadlily (Clintonia uniflora)-western rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia)-twinflower (Linnea borealis)/moss. State 2 is different than State 1 in that western white pine no longer plays a significant role in the seral communities. It has been dramatically reduced in numbers and area by the epidemics of white pine blister rust and western spruce budworm, and by dramatic fire suppression. Therefore, climax species have been able to fill the seral role that western white pine once held. As well, more forests are progressing to the climax or Reference Phase than historically, when most forests were in the fire-maintained western white pine-dominated seral phase. State 2 forests are now dominated by the shade-tolerant climax species western redcedar and western hemlock. While there is a tremendous effort to bolster the numbers of western white pine, it currently covers only 5 percent of its historic range. This ecological site is described as having moderately cool and moist site conditions. The Reference state is dominated by western redcedar and western hemlock, both of which are shade-tolerant climax conifers that grow in similar environments. Western redcedar has a larger geographic extent in Montana, but western hemlock usually is capable of attaining dominance over western redcedar and other species at climax because it is better able to reproduce under a dense forest canopy. Western redcedar is able to maintain itself indefinitely as a minor climax species because of its shade tolerance, longevity (often 600-1,000 years), and apparent ability to regenerate vegetatively (USFS H.T. Guide, 1973). Within Glacier NP, these species are co-dominant in nearly all of the sites visited. The seral successional stages have very diverse overstory tree composition and can be very productive in terms of basal area. Douglas-fir, western larch and, to a lesser extent, spruce are often dominants in seral stands with lodgepole, western white pine, and paper birch as minor components. Grand fir and subalpine fir can be either minor seral or climax components. Western redcedar and western hemlock will regenerate after disturbance along with seral species, and it will take centuries for these species to gain dominance in the overstory over the seral species. The early successional phase can be dominated by fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium). The understory in seral successional phases have moisture-loving forbs or shrubs including Scouler’s willow, thimbleberry, serviceberry, rocky mountain maple, thinleaf huckleberry, and snowbush ceanothus. The historic fire regime of these forests is one of low fire frequency, but fire severity can be highly variable. It can be low due to the most common moist conditions, but can be severe during times of drought. Fire return intervals range from 50 to greater than 200 years, but include mixed severity fires on 50-85 year intervals, as well as stand replacement fires on 150-250 year intervals. Western redcedar can thrive for centuries on this ecological site without disturbance. The Northern Rocky Mountain mesic montane mixed-conifer forest-cedar groves are in fire regime group 5 and had a fire interval of 334 years, with 87 percent of fires classified as of replacement severity and 13 percent of fires classed as mixed severity and none as low severity (USDA, USFS, FEIS, Fire Regime). Fuel loadings for this ecological site can be very high due to deadfall and natural thinning of small and medium-sized branches. In early and intermediate successional phases, the understory can have high cover adding to fuel loadings. Due to the generally moist conditions, fire return intervals can be long. In general, the variability in fire regime and the high diversity of tree species present in most stands, except the Reference, allow this ecological site to form a diverse mosaic landscape with varying dominance or mixes of seral species.

Community 2.1

Reference Community

Western redcedar-western hemlock/prince’s plume-queencup beadlily-western rattlesnake plantain-twinflower/moss

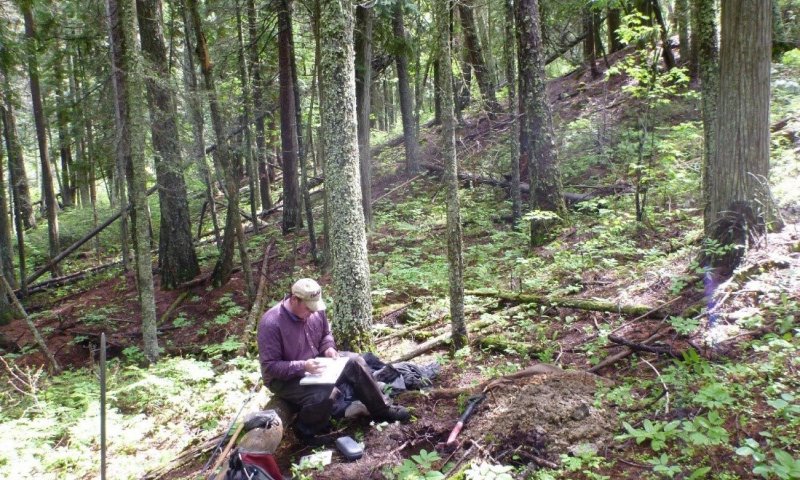

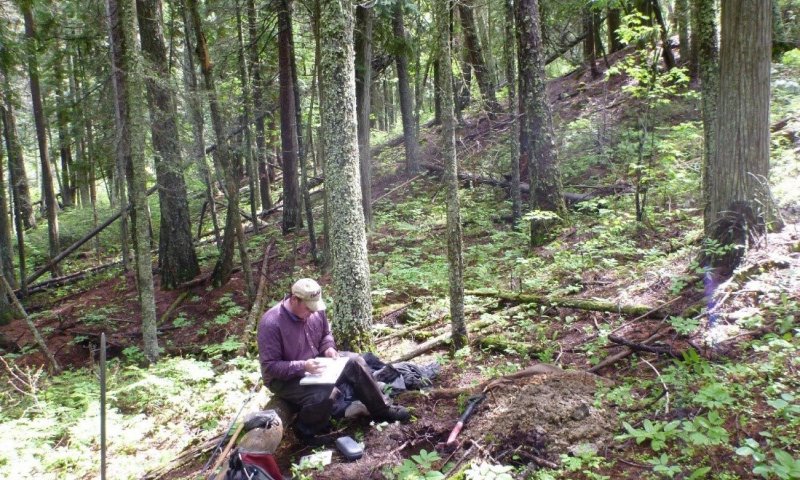

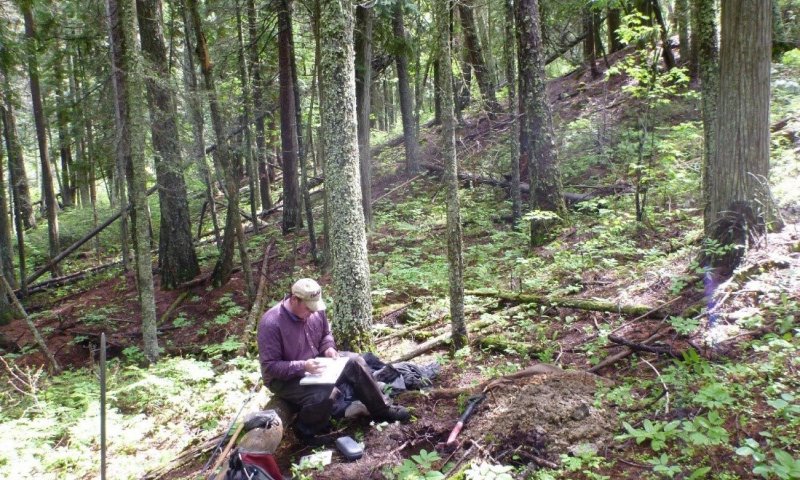

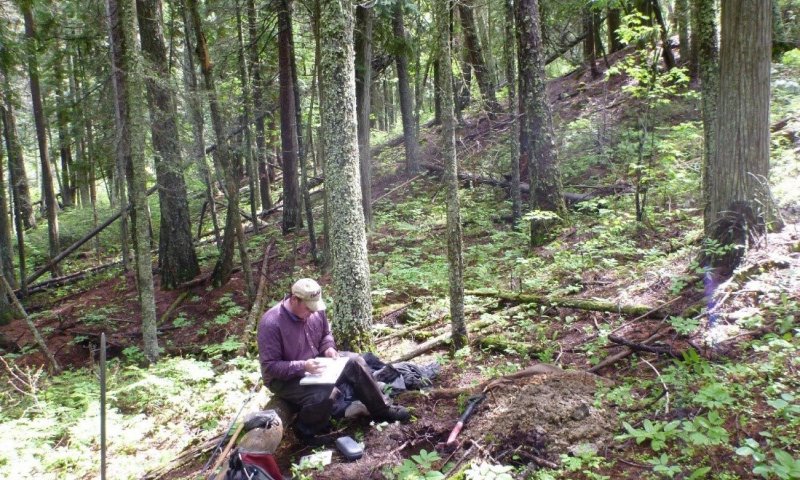

Figure 8. Vegetation community in the reference phase.

Figure 9. Vegetation at a reference site, noting multi-storied understory.

The Reference Community is dominated by western cedar and western hemlock, with seral tree species constrained to less than 3% of the overstory canopy. The ground cover consists predominantly of duff with fairly high cover of moss and trace cover of embedded litter and stones. The vegetation structure is that of very tall trees from 500-1,100 inches tall of western larch, western redcedar and western hemlock. The understory is multistoried though fairly sparse. Species occurring with the highest frequency of occurrence include thinleaf huckleberry, darkwoods violet, twinflower, western rattlesnake plantain, queencup beadlily and prince’s plume ( 15 sites of canopy cover data). Foliar cover at six sites indicate that the foliar cover is fairly high (50.8%) and the ground cover is primarily litter, which includes woody litter, litter or duff (total is 74%, duff is 63%) and moss (30%). The tallest understory layer is 20-40 inches tall and can include common ladyfern (Athyrium filix-femina), common snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus), white spirea (Spiraea betulifolia), and thinleaf huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum). The lowest layer is less than 10 inches tall and can include fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata), queencup beadlily (Clintonia uniflora), western rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia), twinflower (Linnaea borealis), threeleaf foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata), and Oregon boxleaf (Paxistima myrsinites). The most common seral tree species is western larch. The understory is depauperate of species and cover is very low. Species are shade-loving and include prince’s plume, queencup beadlily, western rattlesnake plantain, and twinflower with a thick cover of moss.

Forest overstory. The forest overstory is dominated by western redcedar and western hemlock forming a tall, mature dense canopy. There are lower canopy layers present, though these are much less than the dominant canopy layer.

Forest understory. The forest understory is composed of a very diverse herbacous and multi-storied shrub layers. Each layer has low cover and can appear clumped in distribution. There is very high cover of moss and duff.

Dominant plant species

-

western redcedar (Thuja plicata), tree

-

western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), tree

-

thinleaf huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum), shrub

-

twinflower (Linnaea borealis), shrub

-

Oregon boxleaf (Paxistima myrsinites), shrub

-

bride's bonnet (Clintonia uniflora), other herbaceous

-

pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata), other herbaceous

-

western rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia), other herbaceous

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

-

common beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax), other herbaceous

Figure 10. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 1-10% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0-5% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0-1% |

| Forb basal cover | 0-5% |

| Non-vascular plants | 10-30% |

| Biological crusts | 0-1% |

| Litter | 40-50% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-5% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-5% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 0-15% |

Table 6. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 0-5% | 1-5% | 0-2% | 1-10% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 0-5% | 1-5% | – | 1-10% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 0-5% | 5-10% | – | 0-5% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 0-10% | 0-5% | – | 0-2% |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 0-10% | 0-5% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | 0-10% | 0-5% | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | 20-30% | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | 30-50% | – | – | – |

| >37 | 0-10% | – | – | – |

Community 2.2

Stand Initiation

Regen: Lodgepole pine-western larch (mixed seral species)/Scouler’s willow-white spirea-thinleaf huckleberry/thimbleberry-Oregon boxwood/fireweed-beargrass/moss

Figure 11. Plant Community 2.2 Post Fire Disturbance Community of Herbaceous and Shrub Species.

Structure: This is a forest in the stand initiation phase, possibly with scattered remnant mature trees; the composition of the seedlings depends on the natural seed sources available. Habeck found that in the vicinity of Lake Mcdonald in Glacier N.P., the dominant seral tree species is Lodgepole pine for 10-25 years post-fire. Afterwards, Western Larch will co-dominant from 25-50 years post-fire with other seral tree species at lower cover. Throughout the entire area of this ecological site, the regeneration will probably be a mixture. Overstory canopy cover is generally less than 10%, but the regeneration tree cover is very high forming a thick carpet. It is a mixture of species including: Lodgepole pine, Western larch, subalpine fir, Paper birch, Engelmann spruce, Western white pine, Black cottonwood, Quaking aspen, Douglas fir, Western redcedar and Western hemlock. The understory is a diverse mixture of herbaceous and shrub species including tall willow species, particularly Scouler’s willow, medium statured shrubs white spirea and thinleaf huckleberry, the low statured shrubs thimbleberry and Oregon boxwood. Herbaceous species include: fireweed, beargrass. Moss cover is variable.

Forest overstory. This is the post disturbance community that develops after a fire. Tree species regenerate from seed in the soil or are wind blown in from off site. The tree seedlings are very diverse and include western hemlock, western redcedar, western larch, lodgepole pine, Engelmann spruce.

Forest understory. The forest understory is very diverse in the multilayered shrubs and herbaceous layers. In particular, the herbaceous layer has many species each occurring in low canopy cover. There are tall shrubs in clumps and medium and low statured shrubs throughout the area. There is a diverse layer of tree regeneration.

Dominant plant species

-

western larch (Larix occidentalis), tree

-

lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), tree

-

Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), tree

-

western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), tree

-

western redcedar (Thuja plicata), tree

-

Scouler's willow (Salix scouleriana), shrub

-

thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), shrub

-

white spirea (Spiraea betulifolia), shrub

-

thinleaf huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum), shrub

-

pinegrass (Calamagrostis rubescens), grass

-

bride's bonnet (Clintonia uniflora), other herbaceous

-

western pearly everlasting (Anaphalis margaritacea), other herbaceous

-

narrowleaf hawkweed (Hieracium umbellatum), other herbaceous

-

fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), other herbaceous

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

-

common beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax), other herbaceous

Table 7. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0-2% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0-5% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0-2% |

| Forb basal cover | 0-5% |

| Non-vascular plants | 30-70% |

| Biological crusts | 0-1% |

| Litter | 10-20% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-5% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-5% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 0-10% |

Table 8. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 0-5% | 0-10% | 0-2% | 0-5% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 0-5% | 0-10% | – | 0-5% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 0-5% | 0-10% | – | 0-5% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 0-5% | 0-10% | – | – |

| >1.4 <= 4 | – | 0-10% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | – | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | – | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | – | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Community 2.3

Intermediate Aged Forest

Lodgepole pine-Douglas fir-Engelmann spruce-western larch-paper birch-subalpine fir-western white pine (western redcedar-western hemlock)/white spirea-snowberry-thinleaf huckleberry/thimbleberry/prince’s plume-queencup beadlily

Figure 12. Plant Community 2.3 Intermediate Aged Forest, Dense Thick Pole Sized Trees.

This community phase is dominated by seral tree species that have matured to pole size and are in the competitive exclusion phase of forest succession. Overstory tree canopy is dense and competition for resources is very high. Canopy cover averages 50%. This community is incredibly diverse in tree species including: Lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, Engelmann spruce, Western larch, Paper birch, subalpine fir, Western white pine, Western redcedar and Western hemlock. The overstory canopy of Western redcedar and Western hemlock is less than 3% as they are just beginning to become established. The understory can have high cover of the medium sized shrubs white spirea, snowberry, Oregon boxleaf, common snowberry and thinleaf huckleberry. The short statured thimbleberry can have high cover. The herbaceous layer is diverse, with medium statured beargrass occurring frequently and sometime in high cover. Other herbaceous species include the short statured prince’s plume, queencup beadlily, trailplant and twinflower.

Forest overstory. verstory tree canopy is dense and competition for resources is very high. Canopy cover averages 50%. This community is incredibly diverse in tree species including: Lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, Engelmann spruce, Western larch, Paper birch, subalpine fir, Western white pine, Western redcedar and Western hemlock. The overstory canopy of Western redcedar and Western hemlock is less than 3% as they are just beginning to become established.

Forest understory. The understory can have high cover of the medium sized shrubs white spirea, snowberry, Oregon boxleaf, common snowberry and thinleaf huckleberry. The short statured thimbleberry can have high cover. The herbaceous layer is diverse, with medium statured beargrass occurring frequently and sometime in high cover. Other herbaceous species include the short statured prince’s plume, queencup beadlily, trailplant and twinflower.

Dominant plant species

-

western larch (Larix occidentalis), tree

-

lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), tree

-

western redcedar (Thuja plicata), tree

-

western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), tree

-

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), tree

-

subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), tree

-

western white pine (Pinus monticola), tree

-

paper birch (Betula papyrifera), tree

-

Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), tree

-

thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), shrub

-

white spirea (Spiraea betulifolia), shrub

-

common snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus), shrub

-

thinleaf huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum), shrub

-

pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata), shrub

-

twinflower (Linnaea borealis), shrub

-

Oregon boxleaf (Paxistima myrsinites), shrub

-

pinegrass (Calamagrostis rubescens), grass

-

bride's bonnet (Clintonia uniflora), other herbaceous

-

American trailplant (Adenocaulon bicolor), other herbaceous

-

western rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia), other herbaceous

-

feathery false lily of the valley (Maianthemum racemosum), other herbaceous

-

common beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax), other herbaceous

-

starry false lily of the valley (Maianthemum stellatum), other herbaceous

-

sweetcicely (Osmorhiza berteroi), other herbaceous

-

claspleaf twistedstalk (Streptopus amplexifolius), other herbaceous

-

western meadow-rue (Thalictrum occidentale), other herbaceous

-

threeleaf foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata), other herbaceous

-

darkwoods violet (Viola orbiculata), other herbaceous

Table 9. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 1-10% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 1-5% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0-2% |

| Forb basal cover | 1-5% |

| Non-vascular plants | 10-60% |

| Biological crusts | 0-1% |

| Litter | 30-40% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-5% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-5% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 0-10% |

Table 10. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 0-5% | 0-10% | 0-2% | 0-5% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 0-5% | 0-10% | 0-2% | 0-5% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 0-5% | 0-10% | – | 0-5% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 0-5% | 0-10% | – | – |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 0-5% | 0-5% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | 0-5% | 0-5% | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | 20-60% | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | – | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Community 2.4

Maturing Forest

Western redcedar-western hemlock-subalpine fir-lodgepole pine-Engelmann spruce-western white pine/thinleaf huckleberry-snowberry-white spirea/wild sarsaparilla-heartleaf arnica-queencup beadlily-twinflower-beargrass/moss

Figure 13. Plant Community 2.4 Maturing Forest Phase of Seral Tree Species and Western Redcedar and Western Hemlock

Structure: This community is a maturing forest with vertical differentiation in the overstory tree canopy. Canopy cover averages 60%. This community has diverse tree species with Western redcedar and Western hemlock ranging 3-15% each and other seral tree species about equally distributed. These species include: Subalpine fir, Lodgepole pine, Engelmann spruce, Western white pine. The understory has patchy medium sized shrubs including: thinleaf huckleberry, snowberry, white spirea. There is a diverse understory of herbaceous species including: wild sarsaparilla, heartleaf arnica, queencup beadlily, twinflower and beargrass. There can be high cover of moss.

Forest overstory. The forest overstory is very diverse with seral tree species and western redcedar and western hemlock. The seral tree species include subalpine fir, western larch, lodgepole pine, Engelmann spruce, western white pine and Douglas fir.

Forest understory. The forest understory is multi-storied with shrubs and a lower diverse herbaceous layer. The taller shrubs occur as clumps and have very low cover, while the medium and low shrub layers have moderate cover and are very diverse. The herbaceous layer is very diverse with each species having only very low cover.

Dominant plant species

-

subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), tree

-

western larch (Larix occidentalis), tree

-

lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), tree

-

Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), tree

-

western white pine (Pinus monticola), tree

-

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), tree

-

western redcedar (Thuja plicata), tree

-

western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), tree

-

thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), shrub

-

rusty menziesia (Menziesia ferruginea), shrub

-

twinflower (Linnaea borealis), shrub

-

Oregon boxleaf (Paxistima myrsinites), shrub

-

white spirea (Spiraea betulifolia), shrub

-

common snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus), shrub

-

pinegrass (Calamagrostis rubescens), grass

-

bride's bonnet (Clintonia uniflora), other herbaceous

-

wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), other herbaceous

-

starry false lily of the valley (Maianthemum stellatum), other herbaceous

-

common beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax), other herbaceous

-

western brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum), other herbaceous

-

heartleaf arnica (Arnica cordifolia), other herbaceous

Community 2.5

Mature Forest

Western redcedar-western hemlock (remnant seral species)/thinleaf huckleberry/threeleaf foamflower-prince’s plume-queencup beadlily-western rattlesnake plantain/moss

Figure 14. Plant Community 2.5 Mature forest with some small gap dynamics, remnant seral tree species and western redcedar and western hemlock dominant.

Structure: Mature forest with vertical differentiation in the stand. Overstory is dominated by Western redcedar and Western hemlock although seral tree species are present and can have up to 15% cover each. Overstory canopy cover ranges 50-80%. Western larch is the most common seral species but others include: Grand fir, subalpine fir, Paper birch, Lodgepole pine, Western white pine, and Douglas fir. The understory is diverse but generally has low overall cover. Thinleaf huckleberry occurs in clumps and queencup beadlily and western rattlesnake plantain are common.

Forest overstory. The forest overstory is composed of western redcedar and western hemlock and less cover of seral species.

Forest understory. The forest understory is diverse with medium statured shrubs having the most cover compared to the lower herbaceous layer and the tall and low shrub layers.

Dominant plant species

-

western redcedar (Thuja plicata), tree

-

western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), tree

-

thinleaf huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum), shrub

-

bride's bonnet (Clintonia uniflora), other herbaceous

-

western rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia), other herbaceous

Table 11. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0-10% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0-10% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0-1% |

| Forb basal cover | 0-2% |

| Non-vascular plants | 30-60% |

| Biological crusts | 0-1% |

| Litter | 20-40% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-5% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-5% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 0-10% |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

This pathway represents a major stand-replacement disturbance such as a high-intensity fire, large scale wind event, or major insect infestation.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.3

This pathway represents growth over time with no further significant disturbance. The areas of regeneration pass through the typical stand phases-competitive exclusion, maturation, understory reinitiating-until they resemble the old-growth structure of the reference community.

Pathway 2.3B

Community 2.3 to 2.2

This pathway represents a major stand-replacement disturbance such as a high-intensity fire, large scale wind event, or major insect infestation.

Pathway 2.3A

Community 2.3 to 2.4

This pathway represents continued growth over time with no further major disturbance.

Pathway 2.4B

Community 2.4 to 2.2

This pathway represents a major stand-replacement fire disturbance, such as a major insect outbreak, or major fire event which leads to the stand initiation phase of forest development.

Pathway 2.4A

Community 2.4 to 2.5

This pathway represents continued growth over time with no further major disturbance.

Pathway 2.5A

Community 2.5 to 2.1

This pathway represents no further major disturbance. Continued growth over time, as well as ongoing mortality, leads to continued vertical diversification. The community begins to resemble the structure of the reference community, with small pockets of regeneration and a more diversified understory.

Pathway 2.5B

Community 2.5 to 2.2

This pathway represents a major stand-replacement fire disturbance leading to the stand initiation phase of forest development.

State 3

Armillaria Root Rot Shrubland

Another disease affecting this ecological site is root rot. While Douglas-fir, grand fir, and subalpine fir are most susceptible, western redcedar and western hemlock can be affected as well. Armillaria root disease is the most common root disease fungus in this region, and is especially prevalent west of the Continental Divide. It may be difficult to detect until it has killed enough trees to create large root disease pockets or centers, ranging in size from a fraction of an acre to hundreds of acres. The root disease spreads from an affected tree to its surrounding neighbors through root contact. The root disease effects the tree species most susceptible first, leaving less susceptible tree species that mask its presence. When root rot is severe, the pocket has abundant regeneration or dense brush growth in the center. Western redcedar is moderately resistant to Armillaria root rot in Idaho and Montana. The common disease expression is some mortality in saplings, and residuals of partial harvests often develop severe infections but are very slow to die (Hagle, 2010). There has been a link determined between parent material and susceptibility to root disease (Kimsey et al., 2012). Metasedimentary parent material is thought to increase the risk of root disease. Glacier National Park is dominated by metasedimentary parent material and may be more at risk than other areas to root disease (Kimsey et al., 2012). If a stand sustains very high levels of root disease mortality, then a coniferous stand could cross a threshold and become a shrubland, once all conifers are gone (Kimsey et al., 2012). Management tactics include to identify the type of Armillaria root disease, and manage for pines and larch. Pre-commercial thinning may improve growth and survival of pines and larch. Avoid harvests that leave susceptible species (usually Douglas-fir or true firs) as crop trees (Hagel, 2010).

Community 3.1

Shrub dominated area

Armillaria root rot induced shrubland state

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Substantial loss of western white pine as a major seral tree species

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Western white pine restored as a major seral tree species

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Significant loss of susceptible tree species at a site due to Armillaria root rot and conversion of the forest to a shrubland

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 2

Conversion of the Armillaria root rot induced shrubland to forest, generally of less susceptible seral tree species and eventually to climax tree species

Additional community tables

Table 12. Community 2.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Mid stature, cool season bunchgrasses | – | ||||

| fescue | FESTU | Festuca | – | 0–10 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 2 | Perennial and annual forbs | – | ||||

| common ladyfern | ATFI | Athyrium filix-femina | – | 0–10 | ||

| threeleaf foamflower | TITR | Tiarella trifoliata | – | 0–10 | ||

| bride's bonnet | CLUN2 | Clintonia uniflora | – | 0–10 | ||

| fireweed | CHAN9 | Chamerion angustifolium | – | 0–10 | ||

| western rattlesnake plantain | GOOB2 | Goodyera oblongifolia | – | 0–10 | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 3 | Shrub and subshrubs | – | ||||

| twinflower | LIBO3 | Linnaea borealis | – | 0–10 | ||

| pipsissewa | CHUM | Chimaphila umbellata | – | 0–10 | ||

| Oregon boxleaf | PAMY | Paxistima myrsinites | – | 0–10 | ||

| white spirea | SPBE2 | Spiraea betulifolia | – | 0–10 | ||

| rose | ROSA5 | Rosa | – | 0–10 | ||

| thinleaf huckleberry | VAME | Vaccinium membranaceum | – | 0–10 | ||

| common snowberry | SYAL | Symphoricarpos albus | – | 0–10 | ||

Table 13. Community 2.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| western hemlock | TSHE | Tsuga heterophylla | Native | 24.4–36.6 | 10–50 | 38.1–127 | – |

| western redcedar | THPL | Thuja plicata | Native | 24.4–36.6 | 10–40 | 38.1–127 | – |

| western redcedar | THPL | Thuja plicata | Native | 12.2–24.4 | 10–30 | 38.1–101.6 | – |

| western hemlock | TSHE | Tsuga heterophylla | Native | 12.2–24.4 | 10–30 | 38.1–101.6 | – |

Table 14. Community 2.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| pinegrass | CARU | Calamagrostis rubescens | – | – | 0.5 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| threeleaf foamflower | TITR | Tiarella trifoliata | – | – | 0.5–15 | |

| green false hellebore | VEVI | Veratrum viride | – | – | 3 | |

| darkwoods violet | VIOR | Viola orbiculata | – | – | 0.5–3 | |

| common beargrass | XETE | Xerophyllum tenax | – | – | 0.5–3 | |

| greenflowered wintergreen | PYCH | Pyrola chlorantha | – | – | 0.5–3 | |

| claspleaf twistedstalk | STAM2 | Streptopus amplexifolius | – | – | 3 | |

| pipsissewa | CHUM | Chimaphila umbellata | – | – | 0.5–3 | |

| bride's bonnet | CLUN2 | Clintonia uniflora | – | – | 0.5–3 | |

| American trailplant | ADBI | Adenocaulon bicolor | – | – | 3 | |

| wild sarsaparilla | ARNU2 | Aralia nudicaulis | – | – | 3 | |

| western rattlesnake plantain | GOOB2 | Goodyera oblongifolia | – | – | 0.5–3 | |

| twinflower | LIBO3 | Linnaea borealis | – | – | 0.5–3 | |

| feathery false lily of the valley | MARA7 | Maianthemum racemosum | – | – | 3 | |