Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R062XY005SD

Wet Subirrigated

Last updated: 2/06/2025

Accessed: 02/27/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 062X–Black Hills

The Black Hills (MLRA 62) is a unique, low lying mountain range situated in the midst of a mixed short and mid-grass prairie. It is a true “Island in the Plains,” as it has geophysical and biological attributes that are unlike the surrounding area. The Black Hills have strong floristic ties to four of the North American biomes: Cordilleran (Rocky Mountain) Forest, Northern Coniferous Forest, Eastern Deciduous Forest, and Grasslands.

MLRA 62 is approximately 3,040 square miles in size; 74 percent is located in South Dakota, and 26 percent is in Wyoming. The towns of Lead, Deadwood, Hill City, and Custer, South Dakota, are in this area. U.S. Highways 16 and 385 cross the MLRA. The Black Hills National Forest, Custer State Park, Mt. Rushmore National Monument, Wind Cave National Park, and Jewel Cave National Monument are located in this MLRA.

This area forms the core of the Black Hills and the Bear Lodge Mountains where the elevation generally ranges between 3,600 to 6,565 feet, however, Black Elk Peak (formerly Harney Peak) rises to 7,242 feet. The slopes vary from moderately sloping on some of the high plateaus to very steeply sloping along drainageways and on peaks and ridges. Narrow valleys generally are gently sloping to strongly sloping.

The Black Hills uplift is the product of the Laramide mountain-building episodes that produced most of the ranges in the Rocky Mountains. Uplift began near the end of the Cretaceous period, 65 million years ago and ended by 35 million years ago (Froiland, 1990). The core of the Black Hills is a plutonic mass of granite with steeply dipping metamorphic rocks, primarily slate and schist, that directly surrounds the granite core. A plateau of Mississippian limestone surrounds the igneous and metamorphic rock core. The Madison limestone is broken around the outer edges of the uplifted area. The Permian Minnekahta limestone forms the outermost boundary of the area. Many other tilted sandstone, shale, and limestone units are exposed like a bathtub ring inside the steeply dipping Madison limestone.

The dominant soil orders in this MLRA are Alfisols (forest soils) and Mollisols (grassland soils). The soils in the area have a frigid or cryic soil temperature regime, a udic or ustic soil moisture regime, and mixed, micaceous, or smectitic mineralogy. They are shallow to very deep, generally are well drained, and are loamy in texture.

The Black Hills MLRA supports open to dense forest vegetation. Ponderosa pine is the dominant species across the Black Hills. White spruce grows at the higher elevations and along the major drainageways. Bur oak is found intermixed with pine in the northern and eastern fringes of the Black Hills, and Rocky Mountain juniper is most common in the southern portion of the Black Hills. Aspen and paper birch are minor components found throughout the Black Hills. Prairie dropseed, roughleaf ricegrass, green needlegrass, poverty oatgrass, Richardson’s needlegrass, slender wheatgrass, and Canada wildrye are the most common native grasses under open forest stands. The most common native shrubs are bearberry, common juniper, grouse whortleberry, poison ivy, and Saskatoon serviceberry.

MLRA 62 land ownership is approximately 47 percent private and 53 percent federal. Rangeland and forestland are split almost equally between private and federal ownership (47 percent each). Minor areas of land are privately owned cropland and urban development. The forestland in this area is used mainly for timber production, recreation, and grazing.

The major resource concerns are soil erosion and surface compaction caused by logging, mining, wildfires, grazing, and urban expansion. The quality of both ground and surface water is another concern, especially in the northern part of the Black Hills. The primary cause for concern is contamination from mine waste and septic systems in areas of rural development and urban expansion (USDA-NRCS, 2006: Ag Handbook 296).

LRU notes

For development of ecological sites, MLRA 62 is divided into three Land Resource Units (LRUs) or physiographic zones (A, B, C, and Y). Each LRU has a set of ecological sites that represents these zones.

The LRU is identified in the Ecological Site ID: R062XY000SD; “062X” identifies the MLRA, and the next letter “Y” identifies the LRU. Note: The organization of Ecological Site IDs will likely change in the future.

The North, LRU-A includes the northern Black Hills and Bear Lodge Mountains. It receives between 22 and 30 inches of annual precipitation and has a frigid soil temperature regime.

The High Central, LRU-B includes the high elevation (> 6,200 feet) central core of the Black Hills, which receives between 25 to 35 inches of annual precipitation and has a cryic soil temperature regime.

The South, LRU-C includes the southern portion of the Black Hills and receives between 17 to 21 inches of annual precipitation and has a frigid soil temperature regime.

One additional grouping of ecological sites that are common to the entire MLRA are designated with a “Y” in the ecological site ID.

Classification relationships

USDA Land Resource Region G—Western Great Plains Range and Irrigated Region:

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 62—Black Hills

US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Level IV Ecoregions of the Conterminous United States:

Black Hills Plateau—17b

Black Hills Core Highlands—17c

USDA Forest Service Ecological Subregions: Sections and Subsections of Conterminous United States:

Black Hills Coniferous Forest Province—M334:

Black Hills Section—334A

Black Hills Limestone Plateau-Core Highlands Subsection—M334Ab

Ecological site concept

The Wet Subirrigated ecological site is found throughout MLRA 62. It is a run-in site located on nearly level alluvial fans, stream terraces, and floodplains. The slopes range from 0 to 3 percent. The soils are very deep and formed in loamy or clayey alluvium of mixed origin. Soils are somewhat poorly drained, with moderate to moderately slow permeability.

A seasonal water table occurs within 1 to 2 feet of the surface. The site is non-saline and non-alkaline.

Vegetation in the Reference State (1.0) is dominated by tall and mid-stature warm- and cool-season grasses and grass-like species. Forbs are common and diverse. Shrub patches can be extensive, and trees can be scattered across the site.

Associated sites

| R062XA020SD |

Loamy Overflow - North The Loamy Overflow ecological site is found adjacent to a stream channel. It can also be adjacent to or immediately below the Wet Subirrigated ecological site. |

|---|---|

| R062XY003SD |

Subirrigated The Subirrigated ecological site is found adjacent to or intermixed with the Wet Subirrigated ecological site. The Subirrigated ecological site has a deeper permanent water table (2-5 feet) compared to the Wet Subirrigated ecological site(1-2 feet). |

Similar sites

| R062XY003SD |

Subirrigated The Subirrigated ecological will have more warm-season grasses and fewer shrubs than the Wet Subirrigated ecological site. |

|---|---|

| R062XA020SD |

Loamy Overflow - North The Loamy Overflow ecological site, both in the northern and southern Black Hills, will have more cool-season grasses, scattered trees, and lower vegetative production than the Wet Subirrigated ecological site. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Salix bebbiana |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Spartina pectinata |

Physiographic features

The Wet Subirrigated ecological site occurs on nearly level alluvial fans, stream terraces, and floodplains.. A permanent water table occurs within 1 to 2 feet of the surface and persists longer than the wettest part of the growing season, typically extending through the month of July.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Valley

> Flood plain

(2) Stream terrace (3) Alluvial fan |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to low |

| Flooding duration | Brief (2 to 7 days) to long (7 to 30 days) |

| Flooding frequency | Occasional to frequent |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 2,900 – 5,000 ft |

| Slope | 3% |

| Water table depth | 12 – 24 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

MLRA 62 is in a microclimate caused by the influence of increased elevation, which leads to increased precipitation, moderate air temperature, and lower wind velocities as compared to the surrounding Great Plains. In general, the Black Hills climate is a continental type: cold in the winter and hot in the summer.

Annual precipitation in MLRA 62 typically increases with elevation and decreases from west to east and from north to south. The average annual precipitation range for MLRA 62 is 18 to 35 inches. Most of the rainfall occurs as frontal storms early in the growing season, in May and June. Some high-intensity, convective thunderstorms occur in July and August. Precipitation in the winter occurs mostly as snow. Twenty to 40 percent of the annual precipitation falls as snow. The annual average snowfall ranges from 23 inches at the lower elevations in the south, to 54 inches in the higher elevations of the central core of the Black Hills.

The average annual temperature varies from 36°F to 48°F. January is the coldest month, with an average temperature of 22°F in the higher elevation of the central core, and 25°F in the southern part of MLRA 62. July is the warmest month, with an average daily temperature of 67°F in the central core, and 73°F in the southern part of this MLRA. The frost-free period ranges from 143 to 168 days. It is shortest at higher elevations and in the northwestern part of the MLRA. Hourly winds are estimated to average about 11 miles per hour (mph) annually.

Growth of cool-season plants begins in April, slowing or ceasing growth by mid-August. Warm-season plants begin growth in May and continue to mid-September. Regrowth of cool-season plants may occur in September and October, depending upon soil moisture availability.

The average annual precipitation range for MLRA 62 is 18 to 35 inches.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 72-107 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 108-124 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 19-30 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 34-110 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 73-129 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 18-30 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 83 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 110 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 23 in |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 3. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) LEAD [USC00394834], Lead, SD

-

(2) DEADWOOD 2NE [USC00392209], Whitewood, SD

-

(3) DEERFIELD 3 SE [USC00392231], Hill City, SD

-

(4) MT RUSHMORE NATL MEM [USC00395870], Keystone, SD

-

(5) PACTOLA DAM [USC00396427], Rapid City, SD

-

(6) CUSTER CO AP [USW00094032], Custer, SD

-

(7) EDGEMONT 23 NNW [USC00392565], Custer, SD

-

(8) WIND CAVE [USC00399347], Buffalo Gap, SD

-

(9) DEADWOOD [USC00392207], Deadwood, SD

Influencing water features

Riparian areas and wetland features can be directly associated with the Wet Subirrigated ecological site.

Wetland description

Stream Type: B6, C6

(Rosgen System)

Soil features

Soils common to the Wet Subirrigated ecological site are very deep and formed in alluvium. Subsurface textures are coarse to moderately fine, with some sites containing up to 15 percent rocks in the subsoil. Soils are somewhat poorly drained with moderate to moderately slow permeability. Water-holding capacity is high. These soils have a high water table (1 to 2 feet from the surface) which keeps the rooting zone moist for an extended portion of the growing season. Salinity is none to slight, and sodicity typically is none to slight. Subsurface soil layers are not restrictive to water movement or root penetration.

This site should show no evidence of rills, wind-scoured areas, or pedestalled plants. No water flow patterns are seen on this site. The soil surface is stable and intact.

Major soil correlated to the Wet Subirrigated ecological site is Marshbrook

Marshbrook soil is also correlated to the Subirrigated ecological site (R062XY003SD) if the permanent water table is within 2 to 5 feet of the surface.

These soils are mainly susceptible to water erosion. The hazard of water erosion increases where vegetative cover is not adequate. A drastic loss of the soil surface layer on this site can result in a shift in species composition and production.

More information regarding the soil is available in soil survey reports. Contact the local USDA Service Center for details specific to your area of interest, or go online to access USDA’s Web Soil Survey.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

–

igneous and metamorphic rock

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Loam (2) Clay loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Somewhat poorly drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate to moderately slow |

| Depth to restrictive layer | 80 in |

| Soil depth | 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

6 – 7 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

25% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

4 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

5 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

6.6 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (0-40in) |

15% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (0-40in) |

5% |

Ecological dynamics

The Wet Subirrigated ecological site evolved under Black Hills climatic conditions; light to severe grazing by bison, elk, insects, and small mammals; beaver activities; sporadic, natural or human-caused wildfire (often of light intensities); and other biotic and abiotic factors that typically influence soil and site development. Changes occur in the plant communities due to short-term weather variations, fluctuating water table depth and hydrologic systems, effects of native and non-native plant and animal species, and management actions. Severe disturbances, such as periods of well below-average precipitation, severe defoliation, excessive haying, or non-use and no fire can cause significant shifts in plant communities and species composition.

Placer mining activities during the Black Hills gold rush of the 1870s and 1880s had severe effects in some riparian areas, as did transportation routes along streams, and the expansion of agriculture purposes including farming and livestock production that supplied beef and mutton for mining communities (Froiland, 1990).

In addition, long-term fire suppression following Euro-American settlement of the Black Hills has allowed ponderosa pine on upland forest sites to expand dramatically. Of the average annual precipitation in the Black Hills area, approximately 91.6 percent is returned to the atmosphere via evapotranspiration, about 4.9 percent becomes runoff from the land surface, and about 3.5 percent recharges major Black Hills aquifers (Carter, et al., 2002). These stands of pine also reduce localized aquifer recharge, resulting in drier valley floors and riparian areas.

Interpretations are primarily based on the Prairie Cordgrass-Bluejoint Reedgrass/Nebraska Sedge/Shrubs Plant Community (1.1). It has been determined by study of rangeland relic areas, areas protected from excessive disturbance, and areas under long-term rotational grazing regimes. Trends in plant community dynamics ranging from heavily to lightly grazed areas, seasonal use pastures, and historical accounts also have been used. Plant community phases, states, transitional pathways, and thresholds have been determined through similar studies and experience.

It may be difficult to locate the Reference Plant Community (1.1) with the spread and establishment of non-native cool-season grasses in MLRA 62. The Native/Invaded State (2.0) is more representative of current conditions than the Reference State (1.0). Because of the persistence of non-native cool-season grasses, a restoration pathway to the Reference State (1.0) is not believed to be achievable.

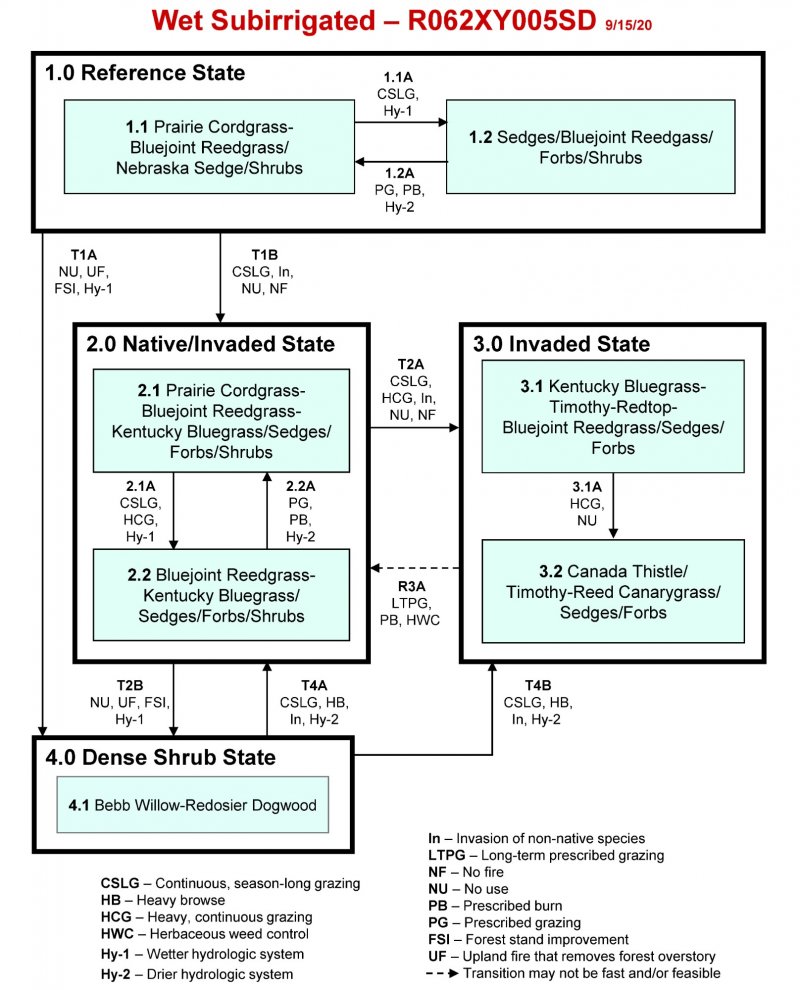

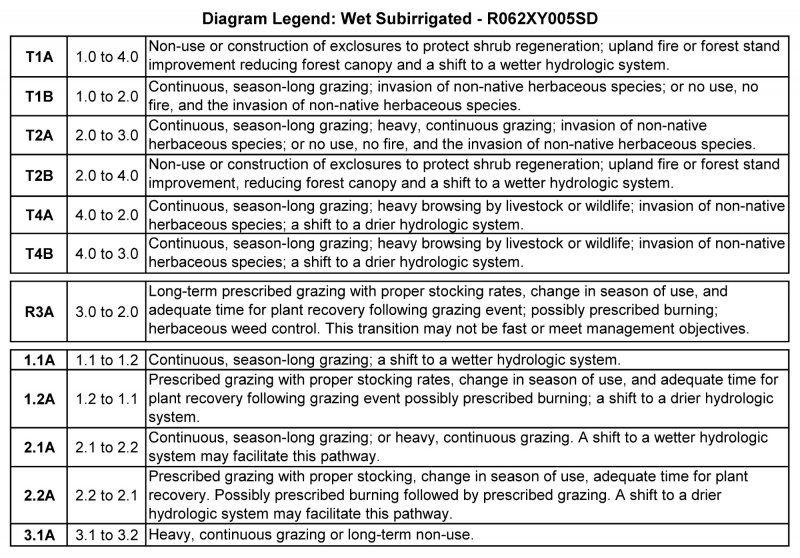

The following state-and-transition diagram illustrates the common plant communities on the site and the transition pathways between communities. The ecological processes are discussed in more detail in the plant community descriptions following the diagram.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State

The Reference State represents what is believed to show the natural range of variability that dominated the dynamics of the Wet Subirrigated ecological site prior to European settlement. This site in the Reference State (1.0) is typically dominated by warm- and cool-season grasses, grass-like species, and thick stands of shrubs. In pre-settlement times, the primary disturbance mechanisms for this site in the Reference condition included periods of below- and above-average precipitation, periodic fire, beaver activity, and herbivory by large ungulates. Timing of fires and herbivory, coupled with weather events, dictated the dynamics that occurred within the natural range of variability. Today the primary disturbances are the lack of fire and concentrated livestock grazing and wildlife browsing. Grasses that are desirable for livestock and wildlife can decline and a corresponding increase in less-desirable grasses will occur. Favorable growing conditions occurred during the spring and the warm months of June through August. Today, a similar state will be difficult to find due to the predominance and invasiveness of non-native cool-season perennial grasses and Canada thistle.

Dominant plant species

-

Bebb willow (Salix bebbiana), shrub

-

yellow willow (Salix lutea), shrub

-

prairie cordgrass (Spartina pectinata), grass

-

bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis), grass

-

cinquefoil (Potentilla), other herbaceous

-

goldenrod (Solidago), other herbaceous

Community 1.1

Prairie Cordgrass-Bluejoint Reedgrass/Nebraska Sedge/Shrubs

Interpretations are based primarily on the Prairie Cordgrass-Bluejoint Reedgrass/Nebraska Sedge/Shrubs Plant Community. This is also considered to be the Reference Plant Community (1.1). This community evolved with beaver activity, grazing and browsing by large herbivores, occasional wildfires, and occasional to frequent flooding events. The potential vegetation was about 80 percent grass and grass-like species, 10 percent forbs, and 10 percent shrubs and trees by air-dry weight. The dominant grasses and grass-likes included prairie cordgrass, bluejoint reedgrass, and Nebraska sedge. Other grass and grass-like species that occurred include northern reedgrass, plains and inland bluegrass, western wheatgrass, and dryspike and inland sedges. Common forbs are cinquefoil, goldenrod, Rocky Mountain iris, Indian hemp, and American licorice. In pre-settlement times, a dense shrub community occurred along stream sides and floodplains throughout the majority of the Black Hills. They consisted of a mixture of several willow species, including Bebb, yellow, and sandbar. Other shrubs included river birch, redosier dogwood, wild rose, raspberry, and currant (Froiland, 1990). These dense shrub components now only occur as scattered patches in the area. This plant community is diverse, stable, and productive, and is well adapted to the Black Hills. The high water table supplies much of the moisture for plant growth. Community dynamics, nutrient and water cycles, and energy flow are functioning properly. Plant litter is properly distributed with very little movement offsite and natural plant mortality is very low. The diversity in plant species allows for the variability of the water table. This is a sustainable plant community in terms of soil stability, watershed function, and biologic integrity.

Figure 7. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 3560 | 3634 | 4255 |

| Forb | 220 | 575 | 650 |

| Shrub/Vine | 220 | 345 | 500 |

| Tree | 0 | 46 | 95 |

| Total | 4000 | 4600 | 5500 |

Figure 8. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). SD6210, Black Hills, lowland warm-season dominant. Lowland warm-season dominant.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 15 | 21 | 26 | 15 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Community 1.2

Sedges/Bluejoint Reedgrass/Forbs/Shrubs

This plant community evolved under continuous, season-long grazing, (grazing at moderate to heavy stocking levels for the full growing season each year) without adequate recovery periods following each grazing occurrence; and a wetter hydrologic system. The potential plant community was made up of approximately 80 percent grasses and grass-like species, 10 percent forbs, and 10 percent shrubs and trees. Dominant grass and grass-like species include dryspike, inland, slough, and clustered field sedges, and bluejoint reedgrass. Other grass and grass-like species include prairie cordgrass, northern reedgrass, plains bluegrass, and rushes. Forbs commonly found in this plant community included goldenrod, cinquefoil, Indian hemp, and cattails. Shrubs include Bebb willow, redosier dogwood, and shrubby cinquefoil. When compared to the Prairie Cordgrass-Bluejoint Reedgrass/Nebraska Sedge/Shrubs Plant Community (1.1), sedges, bluejoint reedgrass, and hydrophytic plant species have increased. Prairie cordgrass and Nebraska sedge have decreased. This plant community is resistant to change. The herbaceous species present were well adapted to grazing; however, species composition could be altered through long-term overgrazing and/or a shift to a drier hydrologic system.

Figure 9. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). SD6207, Black Hills, lowland cool-season dominant, warm-season sub-dominant. Lowland cool-season dominant, warm-season sub-dominant.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 20 | 25 | 18 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Continuous, season-long grazing without adequate recovery periods; the establishment of a wetter hydrologic system will convert the Prairie Cordgrass-Bluejoint Reedgrass/Nebraska Sedge/Shrubs Plant Community (1.1) to the Sedge/Bluejoint Reedgrass/Forbs/Shrubs Plant Community (1.2).

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Prescribed grazing with proper stocking rates, change in season of use, and adequate time for plant recovery; a shift to a drier hydrologic system will shift this plant community to the Prairie Cordgrass-Bluejoint Reedgrass/Nebraska Sedge/Shrubs Plant Community (1.1). Prescribed burning followed by prescribed grazing may also help facilitate this plant community shift.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 2

Native/Invaded State

The Native/Invaded State represents the more common range of variability that exists with higher levels of grazing management but in the absence of periodic fire due to fire suppression. This state is dominated by warm- and cool-season grasses and sedges and can be found on areas that are properly managed with grazing and prescribed burning, and sometimes on areas receiving occasional short periods of rest. Native warm- and cool-season grasses and sedges will decline as non-native cool-season grasses increase. Non-native cool-season grasses will make up less than 15 percent of total annual production. Preliminary studies indicate that when Kentucky bluegrass exceeds 30 percent of the plant community and native grasses represent less than 40 percent of the plant community composition, a threshold has been crossed to an Invaded State (3.0). These invaded plant communities dominated by Kentucky bluegrass will have significantly less cover and diversity of native grasses and forb species (Toledo, D. et al., 2014).

Dominant plant species

-

shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa), shrub

-

Bebb willow (Salix bebbiana), shrub

-

prairie cordgrass (Spartina pectinata), grass

-

bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis), grass

-

American licorice (Glycyrrhiza lepidota), other herbaceous

-

cinquefoil (Potentilla), other herbaceous

Community 2.1

Prairie Cordgrass-Bluejoint Reedgrass-Kentucky Bluegrass/Sedges/Forbs/Shrubs

This plant community phase is similar to the Prairie Cordgrass-Bluejoint Reedgrass/Nebraska Sedge/Shrubs Plant Community (1.1), but it contains minor amounts of non-native invasive grass species such as Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and timothy (up to about 15 percent by air-dry weight). The potential vegetation is about 80 percent grass and grass-like species, 10 percent forbs, and 10 percent shrubs by air-dry weight. The dominant grasses include prairie cordgrass and bluejoint reedgrass. Other grass and grass-like species that occur are various lowland sedges, northern reedgrass, western wheatgrass, and inland bluegrass. Common forbs are American licorice, cinquefoil, goldenrod, mint, and non-native clovers. Canada thistle will likely be present. Typical shrubs include shrubby cinquefoil, Bebb and yellow willow species, and redosier dogwood. This plant community is resilient and well adapted to the Black Hills climatic conditions. This is a sustainable plant community in regard to site and soil stability, watershed function, and biologic integrity.

Figure 10. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). SD6207, Black Hills, lowland cool-season dominant, warm-season sub-dominant. Lowland cool-season dominant, warm-season sub-dominant.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 20 | 25 | 18 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Community 2.2

Bluejoint Reedgrass-Kentucky Bluegrass/Sedges/Forbs/Shrubs

This plant community is a result of continuous season-long grazing, or heavy grazing without adequate recovery periods. The potential plant community is made up of approximately 80 percent grasses and grass-like species, 10 percent forbs, and 10 percent shrubs and trees. Dominant grass and grass-like species include bluejoint reedgrass, various lowland sedges, Kentucky bluegrass, and timothy. Other grass and grass-like species include inland bluegrass, plains bluegrass, and spikerush. Forbs commonly found in this plant community include goldenrod, cinquefoil, non-native clovers, and Canada thistle. Shrubs include yellow willow, redosier dogwood, and shrubby cinquefoil.

Figure 11. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). SD6207, Black Hills, lowland cool-season dominant, warm-season sub-dominant. Lowland cool-season dominant, warm-season sub-dominant.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 20 | 25 | 18 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Continuous, season-long grazing or heavy, continuous grazing without adequate recovery periods will convert Plant Community 2.1 to the Bluejoint Reedgrass-Kentucky Bluegrass/Sedges/Forbs/Shrubs Plant Community (2.2). A shift to a wetter hydrologic system may also facilitate this transition.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Prescribed grazing with proper stocking rates, change in season of use, and adequate time for plant recovery, will shift Plant Community 2.2 to the Prairie Cordgrass-Kentucky Bluegrass/Sedges/Forbs/Shrubs Plant Community (2.1). Prescribed burning followed by prescribed grazing may also help facilitate this plant community shift. A shift to a drier hydrologic system may facilitate this transition.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 3

Invaded State

The Invaded State is the result of invasion and dominance by non-native cool-season grass species. Dominant grasses include Kentucky bluegrass, timothy, and redtop. Continuous, season-long grazing or heavy, continuous grazing will result in an increase of non-native grasses and forbs. Non-use and no fire will result in an increasing thatch layer that tends to favor the more shade-tolerant non-native grass species. The nutrient cycle is impaired, resulting in a higher level of nitrogen which also favors introduced species. Studies indicate that soil biological activity is altered, and this shift apparently exploits the soil microclimate and encourages growth of the non-native grass species. Once the threshold is crossed, a change in grazing management alone cannot cause a reduction in the dominance of invasive grasses. Preliminary studies indicate this threshold may exist when Kentucky bluegrass exceeds 30 percent of the plant community and native grasses represent less than 40 percent of the plant community composition. Plant communities dominated by Kentucky bluegrass have significantly less cover and diversity of native grasses and forb species (Toledo, D. et al., 2014).

Dominant plant species

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

-

timothy (Phleum pratense), grass

-

cinquefoil (Potentilla), other herbaceous

-

red clover (Trifolium pratense), other herbaceous

-

Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense), other herbaceous

Community 3.1

Kentucky Bluegrass-Timothy-Redtop-Bluejoint Reedgrass/Sedges/Forbs

This plant community is a result of continuous, season-long grazing or heavy, continuous grazing, or extended periods of non-use and no fire. It is characterized by a dominance of Kentucky bluegrass, timothy, redtop, and bluejoint reedgrass. Native sedges and forbs will still be present, but red and white clover and Canada thistle will likely be increasing. Native shrubs will decline or be removed from the plant community as regeneration is reduced due to the thick herbaceous sod.

Figure 12. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). SD6206, Black Hills, lowland cool-season dominant. Lowland cool-season dominant.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 6 | 15 | 20 | 26 | 17 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Community 3.2

Canada Thistle/Timothy-Reed Canarygrass/Sedges/Forbs

This plant community is a result of heavy, continuous grazing, or long-term non-use. It is characterized by a dominance of Canada thistle, timothy, redtop and reed canarygrass. The dominance of these species can be so complete that other species are difficult to find on the site. A relatively thick duff layer can sometimes accumulate at or above the soil surface. Nutrient cycling is greatly reduced, and native plants have great difficulty becoming established. Production will be significantly reduced when compared to the interpretive plant community (1.1). Native sedges and forbs may still be present. Red and white clover will likely be increasing, and native shrubs will be essentially be absent in this plant community.

Figure 13. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). SD6206, Black Hills, lowland cool-season dominant. Lowland cool-season dominant.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 6 | 15 | 20 | 26 | 17 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Pathway 3.1A

Community 3.1 to 3.2

Heavy continuous grazing without adequate recovery periods, or extended periods of non-use will convert the 3.1 plant community to the Canada Thistle/Timothy-Reed Canarygrass/Sedges/Forbs Plant Community (3.2).

State 4

Dense Shrub State

In the time prior to European settlement, the Dense Shrub State was common along most streams and floodplains throughout the majority of the Black Hills. Today this community is of minor extent. Prior to settlement, conifer density (primarily ponderosa pine and white spruce) was lower in the uplands, resulting in lower evapotranspiration rates and higher water yields into stream hydrologic systems. The dense shrub plant communities consisted of a mixture of several willow species including Bebb, yellow, and sandbar. Other shrubs included river birch, redosier dogwood, wild rose, raspberry, and currant. Beaver dam complexes were also common on most Black Hills drainages which regulated water flow and maintained high water table levels, creating conditions suitable for dense stands of willow and dogwood. By the latter part of the 1800s, beaver numbers were low and restricted to remote areas of the Black Hills. Riparian ecosystems likely degraded rapidly following beaver removal, generating substantial long-lasting effects. Dramatic changes in the functional and structural groups that make up diverse riparian plant communities are a result of physical disturbances from past and present use and management. Non-native plant species, introduced for forage, substantially reduced the shrub communities and the transitional deciduous trees (Parrash,1996).

Dominant plant species

-

Bebb willow (Salix bebbiana), shrub

-

yellow willow (Salix lutea), shrub

-

sandbar willow (Salix interior), shrub

-

river birch (Betula nigra), shrub

-

redosier dogwood (Cornus sericea), shrub

Community 4.1

Bebb Willow-Redosier Dogwood

This plant community occurs only as remnant plant communities in fenced exclosures or other protected areas, and areas managed specifically for the dense shrub plant community. The potential plant community is made up of approximately 10 percent grasses and grass-like species, 10 percent forbs, 75 percent shrubs, and 0 to 5 percent trees. Dominant grass and grass-like species include prairie cordgrass, bluejoint reedgrass, and various lowland sedges. Other grass and grass-like species may include northern reedgrass, inland bluegrass, plains bluegrass, and spikerush. Forbs commonly found in this plant community include goldenrod, cinquefoil, American licorice, mint, and Indian hemp. Dominant shrubs include Bebb, yellow, and sandbar willows, redosier dogwood, wild rose, raspberry, and currant. Other shrubs in this plant community can included meadow willow, and river birch. This plant community is diverse, stable, productive, and is well adapted to the Black Hills climate. The high water table supplies much of the moisture for plant growth. The diversity in plant species allows the water table to vary periodically. This is a sustainable plant community in terms of soil stability, watershed function, and biologic integrity. Species composition can be altered through long-term grazing, browsing, and/or a shift to a permanent drier hydrologic system. The use of chemical herbicides for the control of noxious weeds can also alter this plant community.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 2

Continuous, season-long grazing; heavy, continuous grazing; and the invasion of non-native herbaceous species; or no use and no fire and the invasion of non-native herbaceous species will transition the Reference State (1.0) to the Native/Invaded State (2.0).

Transition T1A

State 1 to 4

Non-use or the construction of enclosures to protect shrub regeneration; upland fires or forest stand improvement that reduce the conifer canopy and allows the site to reestablish a wetter hydrologic system will transition the Reference State (1.0) to the Dense Shrub State (4.0).

Conservation practices

| Forest stand improvement pre-treating vegetation and fuels preceding a prescribed fire |

|---|

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Continuous, season-long grazing, heavy, continuous grazing, and the expansion of invasive non-native grasses and forbs will transition the Native/Invaded State (2.0) to the Invaded State (3.0). Long-term non-use and no fire will also cause the Native/Invaded State (2.0) to transition to the Invaded State (3.0).

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

Non-use or the construction of enclosures to protect shrub regeneration; fires or forest stand improvement that reduces the upland conifer canopy may facilitate the reestablish of a wetter hydrologic system, transitioning the Native/Invaded State (2.0) to the Dense Shrub State (4.0).

Conservation practices

| Forest stand improvement pre-treating vegetation and fuels preceding a prescribed fire |

|---|

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 2

This transition will require long-term prescribed grazing with proper stocking rates, change in season of use, and deferment that provides adequate time for plant recovery. Prescribed burning may be needed to suppress non-native cool-season grass, and herbaceous weed control to treat invasive forbs. These treatments may facilitate a transition from the Invaded State (3.0) to the Native/Invaded State (2.0). This will take a long period of time and recovery may not meet management objectives. Success will largely depend on whether native reproductive propagules remain intact on the site.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

Transition T4A

State 4 to 2

Continuous, season-long grazing, heavy browsing by livestock or wildlife, the invasion of non-native herbaceous species and a shift to a drier hydrologic system will transition the Dense Shrub State (4.0) to the Native/Invaded State (2.0).

Transition T4B

State 4 to 3

Continuous, season-long grazing, heavy browsing by livestock or wildlife, the invasion of non-native herbaceous species and a shift to a drier hydrologic system will transition the Dense Shrub State (4.0) to the Invaded State (3.0).

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Tall and Mid- Warm-Season Grasses | 1380–2300 | ||||

| prairie cordgrass | SPPE | Spartina pectinata | 1380–2300 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 0–92 | – | ||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 0–92 | – | ||

| marsh muhly | MURA | Muhlenbergia racemosa | 46–92 | – | ||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 0–46 | – | ||

| 2 | Cool-Season Rhizomatous Grasses | 690–1380 | ||||

| bluejoint | CACA4 | Calamagrostis canadensis | 230–920 | – | ||

| northern reedgrass | CASTI3 | Calamagrostis stricta ssp. inexpansa | 230–460 | – | ||

| reed canarygrass | PHAR3 | Phalaris arundinacea | 0–230 | – | ||

| western wheatgrass | PASM | Pascopyrum smithii | 92–230 | – | ||

| plains bluegrass | POAR3 | Poa arida | 46–92 | – | ||

| fowl mannagrass | GLST | Glyceria striata | 0–92 | – | ||

| 3 | Cool-Season Bunchgrasses | 46–230 | ||||

| fowl bluegrass | POPA2 | Poa palustris | 46–230 | – | ||

| inland bluegrass | PONEI2 | Poa nemoralis ssp. interior | 46–230 | – | ||

| American sloughgrass | BESY | Beckmannia syzigachne | 0–92 | – | ||

| 4 | Other Native Grasses | 0–62 | ||||

| Grass, perennial | 2GP | Grass, perennial | 0–92 | – | ||

| 5 | Grass-Likes | 460–1150 | ||||

| Nebraska sedge | CANE2 | Carex nebrascensis | 230–920 | – | ||

| inland sedge | CAIN11 | Carex interior | 92–460 | – | ||

| Hood's sedge | CAHO5 | Carex hoodii | 0–230 | – | ||

| bulrush | SCHOE6 | Schoenoplectus | 0–230 | – | ||

| clustered field sedge | CAPR5 | Carex praegracilis | 0–230 | – | ||

| rush | JUNCU | Juncus | 0–230 | – | ||

| scouringrush horsetail | EQHY | Equisetum hyemale | 0–230 | – | ||

| wheat sedge | CAAT2 | Carex atherodes | 0–230 | – | ||

| spikerush | ELEOC | Eleocharis | 46–230 | – | ||

| Grass-like (not a true grass) | 2GL | Grass-like (not a true grass) | 46–230 | – | ||

| 6 | Non-Native Cool-Season Grasses | 0 | ||||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 7 | Forbs | 230–920 | ||||

| American licorice | GLLE3 | Glycyrrhiza lepidota | 46–230 | – | ||

| cinquefoil | POTEN | Potentilla | 46–230 | – | ||

| goldenrod | SOLID | Solidago | 46–230 | – | ||

| Forb, native | 2FN | Forb, native | 46–230 | – | ||

| white prairie aster | SYFA | Symphyotrichum falcatum | 0–138 | – | ||

| white water crowfoot | RAAQ | Ranunculus aquatilis | 0–92 | – | ||

| Indianhemp | APCA | Apocynum cannabinum | 0–92 | – | ||

| mint | MENTH | Mentha | 0–92 | – | ||

| Pennsylvania smartweed | POPE2 | Polygonum pensylvanicum | 0–92 | – | ||

| plantain | PLANT | Plantago | 0–92 | – | ||

| poison hemlock | COMA2 | Conium maculatum | 0–92 | – | ||

| Rocky Mountain iris | IRMI | Iris missouriensis | 0–92 | – | ||

| swamp milkweed | ASIN | Asclepias incarnata | 0–92 | – | ||

| swamp smartweed | POHY2 | Polygonum hydropiperoides | 0–92 | – | ||

| broadleaf cattail | TYLA | Typha latifolia | 0–46 | – | ||

| water hemlock | CICUT | Cicuta | 0–46 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 8 | Shrubs | 230–460 | ||||

| Bebb willow | SABE2 | Salix bebbiana | 230–460 | – | ||

| redosier dogwood | COSE16 | Cornus sericea | 46–230 | – | ||

| blackberry | RUBUS | Rubus | 46–92 | – | ||

| sandbar willow | SAIN3 | Salix interior | 0–92 | – | ||

| shrubby cinquefoil | DAFRF | Dasiphora fruticosa ssp. floribunda | 0–92 | – | ||

| Woods' rose | ROWO | Rosa woodsii | 46–92 | – | ||

| yellow willow | SALU2 | Salix lutea | 46–92 | – | ||

| currant | RIBES | Ribes | 46–92 | – | ||

| diamondleaf willow | SAPL2 | Salix planifolia | 0–92 | – | ||

| meadow willow | SAPE5 | Salix petiolaris | 0–46 | – | ||

| Shrub (>.5m) | 2SHRUB | Shrub (>.5m) | 0–46 | – | ||

| river birch | BENI | Betula nigra | 0–46 | – | ||

|

Tree

|

||||||

| 9 | Trees | 0–92 | ||||

| peachleaf willow | SAAM2 | Salix amygdaloides | 0–92 | – | ||

| Tree | 2TREE | Tree | 0–46 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

The Black Hills and Bear Lodge Mountains of South Dakota and Wyoming are truly a forested island in a grassland sea. To regional Native Americans they are “Paha Sapa,” or “hills that are black”, and from a distance, the ponderosa pine-covered slopes do appear like black hills (Larson, 1999).

The Black Hills and Bear Lodge Mountains are located in the drier areas of a northern mixed-grass prairie ecosystem in which sagebrush steppes to the west yield to grassland steppes to the east. Prior to European settlement, MLRA 62 consisted of diverse grassland, shrubland, and forest habitats interspersed with varying densities of depressional instream wetlands and woody riparian corridors. These habitats provided critical life cycle components for many users. Many species of grassland birds, small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and herds of roaming bison, elk, and pronghorn were among the inhabitants adapted to this semi-arid region. Roaming herbivores, as well as several species of small mammals and insects, were the primary consumers linking the grassland resources to large predators, such as the gray wolf, mountain lion, grizzly bear, and to smaller carnivores, such as the coyote, bobcat, fox, and raptors.

Beaver inhabited surface waters associated with instream wetlands and woody riparian corridors along streams and drainages. Beaver occupation served as a mechanism to maintain water tables along flood plains and valley floors. During pre-European settlement times, the extent of the wet land sites was likely much more widespread and persistent during dry periods; however, excessive trapping and removal since that time has changed the hydrology and limited the extent of these sites while drying former mesic areas throughout the MLRA.

Grazing Interpretations

Production and accessibility of plant communities described in the Wet Subirrigated ecological site can be highly variable. A complete resource inventory is necessary to document plant composition and production. Accurate estimates of carrying capacity should be calculated using vegetative clipping data, animal preference data, and actual stocking records.

Initial suggested stocking rates should be calculated using a base of 912 lb/acre (air-dry weight) per animal-unit-month (AUM). An AUM is defined as the equivalent amount of forage required by a 1,000-pound cow with or without calf, for one month. Use a 25 percent harvest efficiency of preferred and desirable forage species (refer to USDA-NRCS National Range and Pasture Handbook).

Grazing by domestic livestock is one of the major income-producing industries in the area. Rangeland in this area may provide yearlong forage for livestock. During the dormant period, the forage for livestock likely has insufficient protein to meet livestock requirements. Added protein allows ruminants to better utilize the energy stored in grazed plant materials. A forage quality test should be used to determine the level of supplementation needed.

Hydrological functions

This site is dominated by soils in hydrologic groups B and D. Infiltration and runoff potential for this site varies from low to negligible. Refer to the USDA-NRCS National Engineering Handbook, Part 630, for hydrologic soil groups, runoff quantities, and hydrologic curves.

Recreational uses

This site provides opportunities for hunting, hiking, photography, and bird watching. The wide variety of plants that bloom from spring until fall have an aesthetic value that appeals to visitors.

Wood products

No appreciable wood products are typically present on this site.

Other products

Harvesting the seeds of native plants on this site can provide additional income.

Other information

Revision Notes: Provisional

This provisional ecological site description (ESD) has passed quality control (QC) and quality assurance (QA) to ensure that it meets the 2014 National Ecological Site Handbook (NESH) standards for a provisional ecological site description. This site description should not be considered an Approved ESD, as it contains only the foundational site concepts and requires further data collection, site investigations, and final State-and-Transition Model (STM) reviews before it can be used as an Approved ESD meeting NESH standards.

Site Development and Testing Plan

Future work, as described in an official project plan, is necessary to validate the information in this provisional ecological site description. The plan will include field activities for low-, medium-, and high-intensity sampling, soil correlations, and analysis of the data. Annual field reviews should be done by soil scientists and vegetation specialists. Final field review, peer review, quality control, and quality assurance reviews are required to produce the final document.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented here has been derived from NRCS clipping data and other inventory data. Field observations from range-trained personnel were also used. Those involved in developing this site include: Stan Boltz, range management specialist (RMS), NRCS; Dan Brady, soil scientist (SS), NRCS; Mitch Faulkner, RMS, NRCS; Rick Peterson, (RMS), NRCS; Mathew Scott, RMS, USFS; and Jim Westerman, (SS), NRCS. All inventory information and data records are compiled within the Rapid City, SD USDA-NRCS Shared “S” network drive.

Other references

Brown, P. M. and C. Hull-Sieg. 1996. Fire history in interior ponderosa pine communities of the Black Hills, South Dakota, USA, Int. J. Wildland Fire 6(3): 97-105.

Carter, J.M., D.G. Driscoll, and J.E. Williamson. 2002. The Black Hills Hydrology Study, U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations, USGS Fact Sheet FS-046-02.

Cleland, D.T., J.A. Freeouf, J.E. Keys, G.J. Nowacki, C.A. Carpenter, and W.H McNab. 2007. Ecological subregions: Sections and subsections of the conterminous United States. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report WO-76D. https://www.fs.fed.us/research/publications/misc/73326-wo-gtr-76d-cleland2007.pdf (accessed 31 January 2019).

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. LaRoe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deep-water habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service FWS/OBS-79/31.U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency. 2018. EPA level III and level IV ecoregions of the conterminous United States. https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/level-iii-and-iv-ecoregions- conterminous-united-states (accessed 26 April 2018).

Froiland S.G. and R.R. Weedon. 1990. Natural history of the Black Hills and Badlands. Center for Western Studies, Augustana College, Sioux Falls SD.

Gartner, F. R. and W. W. Thompson. 1972. Fire in the Black Hills forest-grass ecotone, South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station, Journal Series No 1115.

Hall, J. S.; Marriott, J. H.; Perot, J. K. 2002. Ecological Conservation in the Black Hills. Minneapolis, MN: The Nature Conservancy.

High Plains Regional Climate Center, University of Nebraska. 2018. http://www.hprcc.unl.edu/ (accessed 6 April 2018).

Hoffman, George R. and, Robert R. Alexander. 1987. Forest vegetation of the Black Hills National Forest of South Dakota and Wyoming: a habitat type classification. Res. Pap. RM-276. USDA-USFS, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Larson, Gary E. and James R. Johnson. 1999. Plants of the Black Hills and Bear Lodge Mountains. South Dakota State University, College of Agriculture and Biological Sciences and Agriculture Experiment Station, Bulletin 732, Brookings, SD.

McIntosh, A.C. 1949. A botanical survey of the Black Hills of South Dakota. Black Hills Engineer. 28 (4): 3-75.

Parrish, J. B., D. J. Herman, D. J. Reyher, and F. R. Gartner. 1996. A Century of change in the Black Hills and riparian ecosystems. Open Prairie: Bulletins 726, Agriculture Experiment Station, South Dakota State University. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_bulletins/726

Shepperd, W. D. and M. A. Battaglia. 2002. Ecology, silviculture, and management of Black Hills ponderosa pine. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-97. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 112 p.

Toledo, D., M. Sanderson, K. Spaeth, J. Hendrickson, and J. Printz. 2014. Extent of Kentucky bluegrass and its effect on native plant species diversity and ecosystem services in the Northern Great Plains of the United States. Invasive Plant Science and Management. 7(4):543–522. Weed Science Society of America.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service. 2017. Black Hills Resilient Landscape Project, Draft Environmental Impact Statement.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2019. Electronic field office technical guide. https://efotg.sc.egov.usda.gov (accessed 24 July 2019).

Soil Survey Staff. 2019. Official soil series descriptions. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/home/?cid=nrcs142p2_053587 (accessed 30 July 2019).

Soil Survey Staff. 2019. Web Soil Survey. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. https://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/App/WebSoilSurvey.aspx (accessed 30 July 2019).

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2006. Land resource regions and major land resource areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. Agriculture Handbook 296. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_050898.pdf (accessed 27 January 2018).

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2014. National ecological site handbook, 1st ed. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/ref/?cid=nrcseprd1291232 (accessed 27 January 2018).

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2012. National engineering handbook, part 630. Hydrology chapters from e-Directives. https://directives.sc.egov.usda.gov/viewerFS.aspx?hid=21422 (accessed 17 January 2018).

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2018. Climate data. National Water and Climate Center. http://www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov/ (accessed 2 December 2018).

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 1997. National range and pasture handbook, rev. 1, 2003. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb1043055.pdf (accessed 7 January 2018).

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2019. National Soil Information System, Information Technology Center. http://nasis.nrcs.usda.gov (accessed 30 July 2019).

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2019. PLANTS database. National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC. http://plants.usda.gov (accessed 30 July 2019).

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2007. National engineering handbook, part 654. Rosgen Stream Classification Technique – Supplemental Materials, Technical Supplement 3E. https://directives.sc.egov.usda.gov/OpenNonWebContent.aspx?content=17833.wba (accessed 4 March 2019).

Wrage, K.J. 1994. The effects of ponderosa pine on soil moisture, precipitation, and understory vegetation in the Black Hills of South Dakota. 158 p. Thesis.

Contributors

Rick L. Peterson

Mitch D. Faulkner

Stan C. Boltz

Approval

Suzanne Mayne-Kinney, 2/06/2025

Acknowledgments

This ecological site description developed by Rick L. Peterson on April 17, 2020.

Nondiscrimination Statement

In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident.

Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English.

To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, available online at https://www.ascr.usda.gov/filing-program-discrimination-complaint-usda-customer and at any USDA office, or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by:

(1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410;

(2) fax: (202) 690-7442; or

(3) email: program.intake@usda.gov.

USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender.

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 02/06/2025 |

| Approved by | Suzanne Mayne-Kinney |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.