Ecological dynamics

Interdunal Lowland ecological sites developed under Northern Great Plains climatic conditions, light to severe grazing by bison and other large herbivores, sporadic natural or human-caused wildfire, and other biotic and abiotic factors that typically influence soil and site development. This continues to be a disturbance driven site with herbivory, fire, and variable climate being the primary disturbances. Changes occur in the plant communities due to short-term weather variations, impacts of native and/or exotic plant and animal species, and management actions.

The introduction of domestic livestock by European settlers along with season-long, continuous grazing had a profound impact on the vegetation of the Interdunal Lowland ecological site. Season-long, continuous grazing causes a repeated removal of the growing point and excessive defoliation of the leaf area of individual warm-season tallgrasses. The resulting reduction in the ability of the plants to harvest sunlight depletes root reserves, subsequently decreasing root mass. The ability of the plants to compete for nutrients is impaired, resulting in decreased vigor and eventual mortality. Species that evade negative grazing impacts through mechanisms such as a growing season adaptation (i.e., cool-season), growing points located near the soil surface, a shorter structure, or reduced palatability will increase. As this site deteriorates, sand bluestem, little bluestem and prairie sandreed will decrease in frequency and production while blue grama and needle and thread increase.

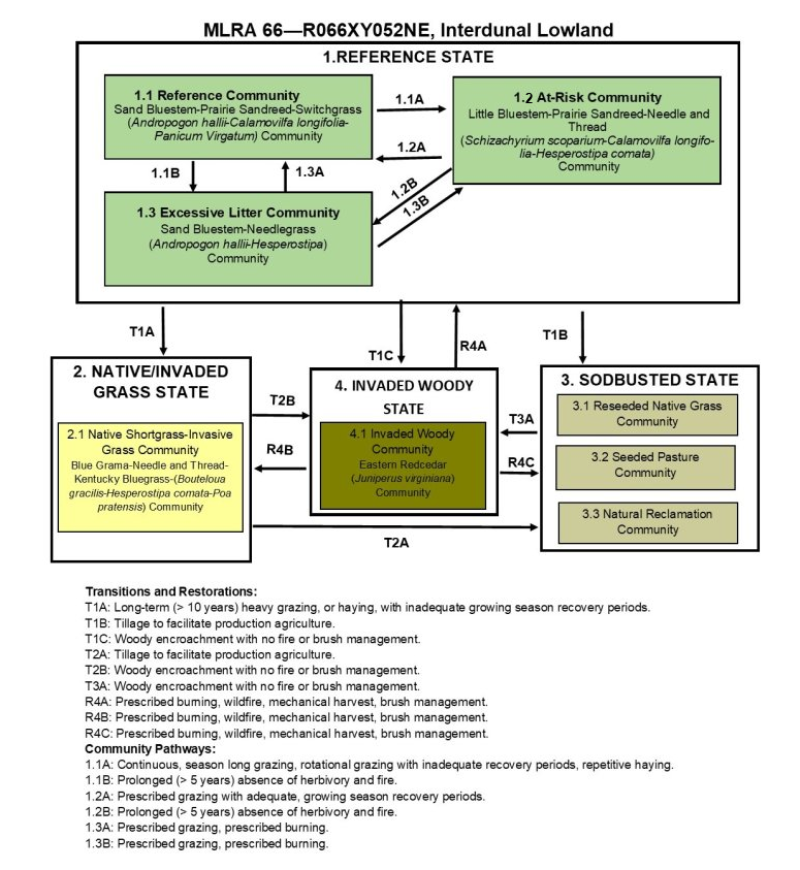

The State-and-Transition Model (STM) is depicted below and includes a Reference State (1), a Native/Invaded Grass State (2), a Sodbusted State (3), and an Invaded Woody State (4). Each state represents the crossing of a major ecological threshold due to alteration of the functional dynamic properties of the ecosystem. The main properties observed to determine this change are the soil and vegetative communities and the hydrologic cycle. Each state may have one or more vegetative communities that fluctuate in species composition and abundance within the normal parameters of the state. Within each state, communities may degrade or recover in response to natural and man-caused disturbances such as variation in the degree and timing of herbivory, presence or absence of fire, and climatic and local fluctuations in the precipitation regime. The processes that cause the movement between the states and communities are discussed in more detail in the state and community descriptions following the diagram.

Interpretations are primarily based on the Reference Community (1.1). It has been determined by study of rangeland relic areas, areas protected from excessive disturbance, and areas under long-term rotational grazing regimes. Trends in plant community dynamics ranging from heavily grazed to lightly grazed areas, seasonal use pastures, and historical accounts have been used as well. Plant communities, states, transitional pathways, and thresholds have been determined through similar studies and experience.

State 1

Reference State

The Reference State (1) describes the range of vegetative communities that occur on the Interdunal Lowland ecological site where the range of natural variability under historic conditions and disturbance regimes is mostly intact. The Reference State developed under the combined influences of climatic conditions, periodic fire activity, grazing by large herbivores, and impacts from small mammals and insects. High perennial grass cover and production allows for increased soil moisture retention, vegetative production and overall soil quality.

The Reference State includes three plant community phases which are the Reference Community (1.1), the At-Risk Community (1.2), and the Excessive Litter Community (1.3). The Reference Community serves as a description of the native plant community that naturally occurs on the site when the natural disturbance regimes are intact or closely mimicked by management practices. The At-Risk Community results from management decisions that are unfavorable for a healthy Reference Community. The Excessive Litter Community occurs when herbivory and fire are eliminated from the landscape.

Community 1.1

Reference Community

Interpretations are primarily based on the Reference Community or Sand Bluestem-Prairie Sandreed-Switchgrass (Andropogon hallii-Calamovilfa longifolia-Panicum virgatum) Community (1.1) This plant community serves as a description of the native plant community that occurs on the site when the natural disturbance regimes are intact or are closely mimicked by management practices. This phase is dynamic, with fluid relative abundance and spatial boundaries between the dominant structural vegetative groups. These fluctuations are primarily driven by different responses of the species to changes in precipitation timing and abundance, and to fire and grazing events. Deep-rooted native warm-season grasses are able to periodically utilize subsurface moisture, giving them a competitive advantage in the community.

Warm-season, tall- and midgrasses dominate this plant community. Sand bluestem, little bluestem, prairie sandreed, switchgrass, and blue grama are the dominant species. Cool-season grasses and grass-like species including needle and thread and various sedges are also present. The forb community is diverse. Leadplant and rose are common shrubs. The potential vegetation is about 80 to 90 percent grasses, 5 to 10 percent forbs and 5 to 10 percent shrubs.

Natural fire played a significant role in the succession of this site by preventing the establishment of eastern redcedar. Wildfires have been actively controlled in recent times, allowing eastern redcedar encroachment. This plant community can be found on areas that are managed with prescribed grazing and prescribed burning. It may be found on areas receiving occasional periods of short-term rest. Management strategies to sustain this community include proper stocking rates, adequate growing season recovery times, monitoring key forage species, and prescribed fire every 6 to 8 years (R. P. Guyette and others, 2012).

This resilient community is well adapted to the Northern Great Plains climatic conditions. Plant diversity promotes strong tolerance to drought, site and soil stability, a functional hydrologic cycle, and a high degree of biological integrity. These factors create a suitable

environment for a healthy and sustainable plant community.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 1.2

At-Risk Community

The At-Risk or Little Bluestem-Prairie Sandreed-Needle and Thread (Schizachyrium scoparium-Calamovilfa longifolia-Hesperostipa comata) Community (1.2) is marked by a significant loss of production. This community develops with continuous season-long grazing or rotational grazing with inadequate recovery periods. Cool-season and warm-season shortgrasses have increased as compared to the Reference Community (1.1). Most of the palatable plants from the Reference Community are present but occur in reduced amounts. The composition of the forb component remains diverse. The potential for encroachment by invasive woody species becomes more likely due to fewer deep-rooted species and a reduced fuel load to carry fire.

The dominant grasses are prairie sandreed and little bluestem. Grasses of secondary importance include blue and hairy grama, needle and thread, sand dropseed, and western wheatgrass. Forbs commonly found in this plant community include white sagebrush, heath aster, goldenrod, hoary verbena, and cuman ragweed. Indiangrass is greatly reduced and may be present only as a remnant while sand bluestem is significantly reduced. Forbs and cool-season grasses are a higher percentage of the community as compared to the Reference Community. The potential vegetation is about 75 to 85 percent grasses or grass-like plants, 10 to 15 percent forbs, and 5 to 10 percent woody shrubs.

As this site deteriorates, more grazing-tolerant species such as prairie sandreed, little bluestem, sand dropseed, and blue grama initially increase, while sand bluestem and switchgrass decrease in frequency and production. The reduction in warm-season tallgrasses not only reduces the annual production but also the ability to increase production in favorable years. The soil surface remains intact and this plant community is considered stable. While this plant community is less productive and less diverse than the Reference Plant Community, it remains sustainable in regard to site and soil stability, hydrologic function, and biotic integrity. Unless the management strategy is changed, prairie sandreed and little bluestem populations will become a smaller portion of the plant community, while warm-season shortgrasses and cool-season grasses will increase causing the community to cross the threshold to the Native/Invaded Grass State (2).

The resiliency of this plant community is moderate depending upon the intensity and duration of disturbance. Infiltration and runoff are generally not affected due to the nature of the soil.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 1.3

Excessive Litter Community

The Excessive Litter or Sand Bluestem-Needlegrass (Andropogon hallii-Hesperostipa) Community (1.3) develops when the natural disturbances of livestock grazing and fire have been removed from the land for a prolonged period of time (more than five years). Periodic fire may extend the amount of time it will take to reach this community. The litter amount has clearly increased and few or no sedges or understory shortgrasses are present. As the undisturbed duff layer deepens, infiltration of the precipitation is interrupted and evaporation increases significantly, simulating drought-like conditions. Typically, bunchgrasses have developed dead centers and rhizomatous grasses have formed small colonies due to a lack of tiller stimulation. Plant frequency and production have decreased. Pedestalling is usually evident.

As compared to the Reference Community (1.1), plant diversity has decreased and native plants tend to occur in individual colonies. This plant community has a high amount of litter covering the soil between widely dispersed mature plants. As the litter layer thickens, the health and vigor of native, warm-season, tall- and midgrasses declines. Soil erosion is low and infiltration and runoff are not significantly different than the Reference Community. This plant community will change rapidly when grazing or fire is returned to the landscape.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

A shift from the Reference Community (1.1) to the At-Risk Community (1.2) occurs with continuous, season-long grazing or rotational grazing with inadequate growing-season recovery periods. Repetitive haying without allowing adequate recovery periods during the growing season will also cause this shift.

Pathway 1.1B

Community 1.1 to 1.3

Prolonged (more than 5 years) interruption of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire will move the Reference Community (1.1) to the Excessive Litter Community (1.3).

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Prescribed grazing with appropriate stocking rates and adequate growing season recovery periods will return the At-Risk Community (1.2) to the Reference Community (1.1). Prescribed fire will accelerate this process. Allowing adequate recovery time during the growing season when the land is hayed will also facilitate return to the Reference Community.

Pathway 1.2 B

Community 1.2 to 1.3

Prolonged (more than 5 years) interruption of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire will move the At-Risk Community (1.2) to the Excessive Litter Community (1.3).

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.1

Reintroduction of the natural processes of herbivory and fire will return the Excessive Litter Community (1.3) to the Reference Community (1.1).

Pathway 1.3B

Community 1.3 to 1.2

Reintroduction of the natural processes of herbivory and fire will return the Excessive Litter Community (1.3) to the At-Risk Community (1.2).

State 2

Native/Invaded Grass State

The Native/Invaded Grass State (2) has been degraded from the Reference State (1) and much of the native, warm-season, tall- and midgrass components have been replaced by native, warm-season shortgrasses and non-native, cool-season grasses. The loss of warm-season, tall- and midgrasses has negatively impacted energy flow and nutrient cycling. Water infiltration is reduced due to the shallow root system and rapid runoff characteristics of the shortgrass dominated communities. The Native/Invaded Grass State includes the Shortgrass Sod Community (2.1).

Community 2.1

Shortgrass Sod Community

The Shortgrass Sod or Blue Grama-Kentucky Bluegrass (Bouteloua gracilis-Poa pratensis) Community (2.1) occurs when a threshold is crossed from the Reference State (1). Most of the warm-season tall- and midgrasses and cool-season bunchgrasses have been removed from the plant community. Plant diversity is low. Small, isolated plants may exist in a prostrate form to avoid defoliation. With the decline and loss of deeper-penetrating root systems, a compacted layer may form in the soil profile below the shallower replacement root systems. This plant community typically develops with heavy livestock grazing, usually season long, or with annual haying followed by fall grazing. It can also develop with long-term (greater than ten years) exclusion of grazing and fire and under this management, Kentucky bluegrass will be the dominant species.

Dominant grasses include needle and thread, blue or hairy grama, and sand dropseed. Kentucky bluegrass may have a significant presence in the plant community. Other grasses or grass-likes include prairie Junegrass, Scribner's rosette grass, western wheatgrass, and sedges. Common forbs include cuman ragweed, hoary verbena, white sagebrush, and heath aster. Pricklypear and rose are the dominant shrubs. Annual haying delays the increase of rose but increases the cactus component. The potential vegetation is about 80 to 90 percent grass or grass-like plants, 5 to 10 percent forbs, and 5 to 10 percent shrubs.

This plant community is fairly resistant to change. Species richness and plant diversity has decreased significantly as compared to the Reference Community (1.1), resulting in a community that is not resilient when disturbed. Plant litter is low, but due to the presence of heavy sod, soil erosion is also low. Water infiltration and runoff are moderate due to soil texture and hydrologic function is negatively affected.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

State 3

Sodbusted State

The threshold to the Sodbusted State (3) is crossed as a result of mechanical disturbance to facilitate production agriculture. If farming operations are suspended, the site can seeded to native grasses and forms resulting in the Reseeded Native Grass Community (3.1), be seeded to a tame pasture forage mixture resulting in the Seeded Pasture Community (3.2), or be abandoned with no seeding which will result in the Natural Reclamation Community (3.3). Permanent alterations of the soil, plant community, and hydrologic cycle make restoration to the Reference State (1) extremely difficult, if not impossible.

Community 3.1

Reseeded Native Grass Community

The Reseeded Native Grass Community (3.1) does not contain native remnants, and varies considerably depending upon the seed mixture, the degree of soil erosion, the age of the stand, fertility management, and past grazing management.

Native range and grasslands seeded to native species are ecologically different and should be managed separately. Factors such as functional group, species, stand density, and improved varieties all impact the production level and palatability of the seedings. Species diversity is often limited, and when grazed in conjunction with native rangelands, uneven forage utilization may occur.

Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending upon precipitation, management, and grass species seeded. Prescribed grazing including appropriate utilization levels, adequate growing-season recovery periods, and timing of grazing that favor the productivity, health, and vigor of the seeded species is required to maintain this community. Periodic prescribed burning and brush management may also be needed.

Community 3.2

Seeded Pasture Community

The Seeded Pasture Community (3.2) does not contain native remnants and varies considerably depending upon the extent of soil erosion, the species seeded, the quality of the stand that was established, the age of the stand, and management of the stand since establishment.

There are several factors that make seeded tame pasture a different grazing resource than native rangeland and land seeded to a native grass mixture. Factors such as species selected, stand density, improved varieties, and harvest efficiency all impact production levels and palatability. Species diversity on seeded tame pasture is often limited to a few species. When seeded pasture and native rangelands or seeded pasture and seeded rangeland are in the same grazing unit, uneven forage utilization will occur. Improve forage utilization and stand longevity by managing this community separately from native rangelands or land seeded to native grass species.

Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending on the level of management and species seeded. Improved varieties of warm-season or cool-season grasses are recommended for optimum forage production. Fertilization, weed management, and prescribed grazing including appropriate utilization levels, adequate growing-season recovery periods, and timing of grazing that favor the productivity, health, and vigor of the seeded species are required to maintain this community. Periodic prescribed burning and brush management may also be needed.

Community 3.3

Natural Reclamation Community

The Natural Reclamation Community (3.3) consists of annual and perennial weeds and less desirable grasses. These sites have been farmed and abandoned without being reseeded. Soil organic matter and carbon reserves are reduced, soil structure is changed, and a plowpan or compacted layer can form, which decreases water infiltration. Residual synthetic chemicals may remain from farming operations. In early successional stages, this community is not stable. The hazard of erosion is a resource concern. Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending on the succession stage of the plant community and any management applied to the system.

State 4

Invaded Woody State

The Invaded Woody State (4) is the result of woody encroachment. Once the tree canopy cover reaches 15 percent with an average tree height exceeding five feet, the threshold is crossed. Woody species are encroaching due to lack of prescribed fire and other brush management practices. Typical ecological impacts are a loss of native grasses, degraded forage productivity, and reduced soil quality.

Prescribed burning, wildfire, timber harvest and brush management will move this state toward a grass dominated state. If the Invaded Woody State transitioned from the Native/Invaded Grass State (2) or the Sodbusted State (3), the land cannot transition to the Reference State (1) as the native plant community, soils, and hydrologic function had been too severely impacted prior to the woody encroachment to allow restoration to the Reference State. This Woody Invaded State includes one community, the Invaded Woody Community (4.1)

Community 4.1

Invaded Woody Community

The Invaded Woody Community or Eastern Redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) Community (4.1) has at least 15 percent canopy cover consisting of trees generally 5 feet or taller. Encroaching trees are primarily eastern redcedar. Additional woody cover from deciduous trees and shrubs may be present. In the absence of fire and brush management, this ecological site is very susceptible to eastern redcedar seedling invasion, especially when adjacent to a seed source. Eastern redcedar can eventually dominate the site resulting in a closed canopy monoculture which drastically reduces forage production and which has limited value for either livestock grazing or wildlife habitat.

With long-term fire suppression, this plant community will develop extensive ladder fuels which can lead to a removal of most tree species with a wildfire. With properly managed intensive grazing, encroachment of deciduous trees will typically be minimal; however, this will not impact encroachment of coniferous species. The herbaceous component decreases proportionately in relation to the percent canopy cover, with the reduction being greater under a coniferous overstory.

Eastern redcedar control can usually be accomplished with prescribed burning while the trees are six feet tall or less and fine fuel production is greater than 1,500 pounds per acres. Larger red cedars can also be controlled with prescribed burning, but successful application requires the use of specifically designed ignition and holding techniques (https://www.loesscanyonsburning group.com). Resprouting brush must be chemically treated immediately after mechanical removal to achieve effective treatment. The forb component will initially increase following tree removal. To prevent return to a woody dominated community, ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments, or periodic prescribed burning is required.

This plant community is resistant to change and resilient given normal disturbances. In higher canopy cover situations, the soil erosion will increase in relation the plant community from which this plant community originated. The hydrologic function is also significantly altered under higher canopy cover. Infiltration is reduced and runoff is typically increased because of a lack of herbaceous cover and the rooting structure provided by the herbaceous species.

Total annual production during an average year varies significantly, depending on the production level prior to encroachment and the percentage of canopy cover.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Heavy, season-long, long-term (more than ten years) grazing or heavy rotational grazing with inadequate recovery periods will cause the Reference State (1) to lose a significant proportion of warm-season, tall-and midgrass species and cross a threshold to the Native/Invaded Grass State (2). This transition will also occur with repetitive haying with inadequate recovery periods. Water infiltration and other hydrologic functions will be reduced due to the root-matting presence of sod-forming grasses. With the decline and loss of deeper-penetrating root systems, soil structure and biological integrity are catastrophically degraded to the point that recovery is unlikely. Once this occurs, it is highly unlikely that grazing management alone will return the community to the Reference State.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The Reference State (1) is significantly altered by tillage to facilitate production agriculture. The disruption to the plant community, the soil, and the hydrology of the system make restoration to a true reference state unlikely.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

Disruption of the natural fire regime and the encroachment of invasive exotic and native woody species can cause the Reference State (1) to shift to the Invaded Woody State (4).

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

The Native/Invaded Grass State (2) is significantly altered by tillage to facilitate production agriculture. The disruption to the plant community, the soil and the hydrology of the system make restoration unlikely.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

Disruption of the natural fire regime and the encroachment of invasive exotic and native woody species can cause the Native/Invaded Grass State (2) to shift to the Invaded Woody State (4).

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Disruption of the natural fire regime and the encroachment of invasive exotic and native woody species can cause the Sodbusted State (3) to shift to the Invaded Woody State (4).

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 1

Prescribed burning, wildfire, harvest, and brush management will move the Invaded Woody State (4) toward the Reference State (1). The forb component may initially increase following tree removal. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments, or periodic prescribed burning is required to prevent a return to the Invaded Woody State. The heavier the existing canopy cover, the greater the energy input required to return to the Reference State by management practices. The amount of time required for this restoration to occur depends on the severity and duration of the encroachment.

Land that transitioned to the Woody Invaded State from the Native/Invaded Grass State (2) or the Sodbusted State (3), cannot transition to the Reference State through removal of woody species as the native plant community, soils, and hydrologic function have been too severely impacted for that restoration to occur.

Restoration pathway R4B

State 4 to 2

Prescribed burning, wildfire, harvest, and brush management will move the Invaded Woody State (4) toward the Native/Invaded Grass State (2). The forb component may initially increase following tree removal. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments, or periodic prescribed burning is required to prevent a return to the Invaded Woody State. The heavier the existing canopy cover, the greater the energy input required to return to the Reference State by management practices. The amount of time required for this restoration to occur depends on the severity and duration of the encroachment.

Land that transitioned to the Woody Invaded State from the Native/Invaded Grass State or the Sodbusted State (3), cannot transition to the Reference State (1) through removal of woody species as the native plant community, soils, and hydrologic function have been too severely impacted for that restoration to occur.

Restoration pathway R4C

State 4 to 3

Prescribed burning, wildfire, harvest, and brush management will move the Invaded Woody State (4) toward the Sodbusted State (3). The forb component may initially increase following tree removal. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments, or periodic prescribed burning is required to prevent a return to the Invaded Woody State. The heavier the existing canopy cover, the greater the energy input required to return to the Reference State by management practices. The amount of time required for this restoration to occur depends on the severity and duration of the encroachment.

Land that transitioned to the Woody Invaded State from the Native/Invaded Grass State (2) or the Sodbusted State (3), cannot transition to the Reference State (1) through removal of woody species as the native plant community, soils, and hydrologic function have been too severely impacted for that restoration to occur.