Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R067BY009CO

Siltstone Plains

Last updated: 12/05/2024

Accessed: 01/02/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

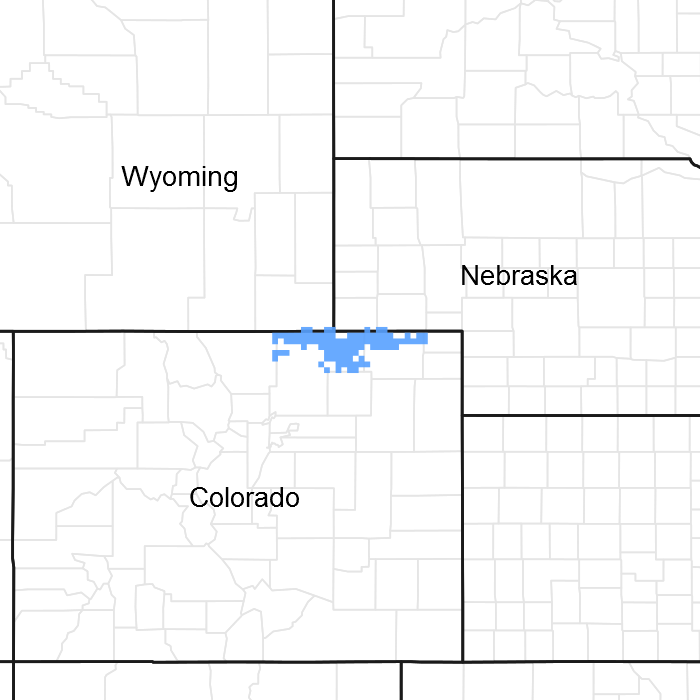

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 067B–Central High Plains, Southern Part

MLRA 67B occurs in eastern Colorado and consists of rolling plains and river valleys. Some canyonlands occur in the southeast portion. The major rivers are the South Platte and Arkansas which flow from the Rocky Mountains to Nebraska and Kansas. Other rivers in the MLRA include the Cache la Poudre and Republican and associated tributaries. This MLRA is traversed by Interstate 25, 70 and 76; and U.S. Highways 50 and 287. Major land uses include 54 percent rangeland, 35 percent cropland, and 2 percent pasture and hayland. Urban, developed open space, and miscellaneous land occupy approximately 9 percent. Major Cities in this area include Fort Collins, Greeley, Sterling, and Denver. Other cities include Limon, Cheyenne Wells, and Springfield. Land ownership is mostly private. Federal lands include Pawnee and Comanche National Grasslands (U.S. Forest Service), Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site (National Park Service), and Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service). State Parks include Cherry Creek and Chatfield Reservoirs, and Barr and Jackson Lakes.

This region is periodically affected by severe drought, including the historic “Dust Bowl” of the 1930s. Dust storms may form during drought years in windy periods. Elevations range from 3,400 to 6,000 feet. The Average annual precipitation ranges from 14 to17 inches per year and ranges from 13 inches to over 18 inches, depending upon location. Precipitation occurs mostly during the growing season, often during rapidly developing thunderstorms. Mean annual air temperature (MAAT) is 48 to 52 degrees Fahrenheit. Summer temperatures may exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Winter temperatures may be sub-zero, and snowfall varies from 20 to 40 inches per year. Snow cover frequently melts between snow events.

LRU notes

Land Resource Unit (LRU) A is the northeast portion of MLRA 67B, to an extent of approximately 9 million acres. Most of the LRU is rangeland, and includes the Pawnee National Grassland. Dryland winter wheat/fallow rotations (that may include dryland corn, sunflowers, and sorghum) are grown in most counties. Irrigated cropland is utilized in the South Platte Valley. Small acreage and urban ownership are more concentrated on the Front Range. This LRU is found in portions of Adams, Arapahoe, Elbert, Kit Carson, Larimer, Lincoln, Logan, Washington, and Weld counties. Other counties include Boulder, Cheyenne, Denver, Jefferson, and Yuma. The soil moisture regime is aridic ustic. The mean annual air temperature (MAAT) is 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

LRU B is in the southeast portion of MLRA 67B (2.6 million acres) and includes portions of Baca, Bent, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Las Animas, and Prowers counties. Most of the LRU remains in rangeland and includes the Comanche National Grassland. On the farmed land, a system of dryland winter wheat/fallow rotations (that may include dryland corn, sunflowers, and sorghum) is implemented. Irrigated cropland is found in the Arkansas Valley. The soil moisture regime is aridic ustic and the MAAT is 52 degrees Fahrenheit.

LRU C occurs in portions of Morgan and Weld counties (approximately 1.2 million acres). Most of LRU C is in rangeland. On the farmed land, a system of dryland winter wheat/fallow rotations (that may include dryland corn, sunflowers, and sorghum) is implemented. The soil moisture regime is ustic aridic and the MAAT is 48 degrees Fahrenheit.

Classification relationships

MLRA 67B is in the Colorado Piedmont and Raton Sections of the Great Plains Province (USDA, 2006). The MLRA is further defined by Land Resource Units (LRUs) A, B, and C. Features such as climate, geology, landforms, and key vegetation further refine these concepts and are described in other sections of the Ecological Site Description (ESD).NOTE: To date, these LRUs are DRAFT.

Relationship to Other Hierarchical Classifications:

NRCS Classification Hierarchy: Physiographic Division, Physiographic Province, Physiographic Section, Land Resource Region, Major Land Resource Area, Land Resource Unit (Fenneman, 1946).

USFS Classification Hierarchy: Domain, Division, Province, Section, Subsection,

Land Type Association: Land Type, Land Type Phase (Cleland et al, 1997).

REVISION NOTES:

The Siltstone Plains Ecological Site Description was developed from an earlier version (2004, revised 2007) which was based on input from the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) (formerly Soil Conservation Service) and historical information obtained from the Siltstone Plains Range Site descriptions (1975). This ESD meets the Provisional requirements of the National Ecological Site Handbook (NESH). This ESD will continue refinement towards an Approved status according to the NESH.

Ecological site concept

The Siltstone Plains Ecological Site is a run-off site on less than six percent slopes. It is deeper than 40 inches to bedrock, and it has less than 15 percent rock fragments on the surface or in the subsoil. The site is not dominated by sandy surface or subsurface textures, and does not have visible salts in the soil profile or at the surface. It does have calcium carbonates at the surface.

Associated sites

| R067BY036CO |

Overflow This ecological site is commonly adjacent. |

|---|---|

| R067BY039CO |

Shallow Siltstone This ecological site is commonly adjacent. |

| R067BY002CO |

Loamy Plains This ecological site is commonly adjacent. |

Similar sites

| R067BY002CO |

Loamy Plains This ecological site does not have calcium carbonates at the surface. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Atriplex canescens |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Pascopyrum smithii |

Physiographic features

This site occurs on fans, footslopes, or toeslopes of the Chalk Bluffs escarpments.

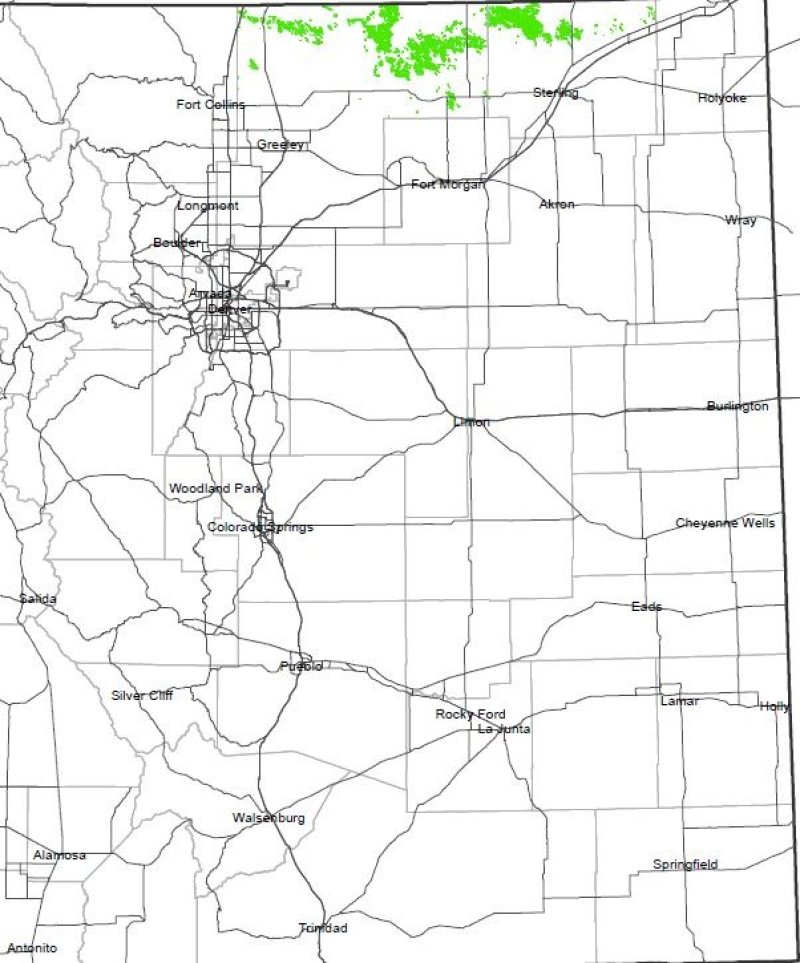

Figure 2. The distribution of the Siltstone Plains site in MLRA 67B.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Fan

|

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to medium |

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 1,158 – 1,707 m |

| Slope | 0 – 6% |

| Ponding depth | 0 cm |

| Water table depth | 203 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

Average annual precipitation across the MLRA extent is 14 to 17 inches, and ranges from 13 to over 18 inches, depending on location. Precipitation increases from north to south. Mean Annual Air Temperature (MAAT) is 50 degrees Fahrenheit in the northern part and increases to 52 degrees Fahrenheit in the southern part. Portions of Morgan and Weld counties are cooler and drier, the MAAT is 48 degrees Fahrenheit, and average precipitation is 13 to14 inches per year.

Two-thirds of the annual precipitation occurs during the growing season from mid-April to late September. Snowfall averages 30 inches per year, area-wide, but varies by location from 20 to 40 inches per year. Winds are estimated to average 9 miles per hour annually. Daytime winds are generally stronger than at night, and occasional strong storms may bring periods of high winds with gusts to more than 90 mph. High-intensity afternoon thunderstorms may arise. The average length of the freeze-free period (28 degrees Fahrenheit) is 155 days from April 30th to October to 3rd. The average frost-free period (32 degrees Fahrenheit) is 136 days from May 11th to September 24th. July is the hottest month, and December and January are the coldest months. Summer temperatures average 90 degrees Fahrenheit and occasionally exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Summer humidity is low and evaporation is high. Winters are characterized with frequent northerly winds, producing severe cold with temperatures occasionally dropping to -30 degrees Fahrenheit or lower. Blizzard conditions may form quickly. For detailed information, visit the Western Regional Climate Center website:

Western Regional Climate Center Historical Data Western U.S. Climate summaries, NOAA Coop Stations Colorado http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/summary/Climsmco.html.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 119-129 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 134-151 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 356-432 mm |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 102-132 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 126-156 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 356-432 mm |

| Frost-free period (average) | 121 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 142 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 381 mm |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 6. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 7. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 8. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) FLAGLER 1S [USC00052932], Flagler, CO

-

(2) FT MORGAN [USC00053038], Fort Morgan, CO

-

(3) KIT CARSON [USC00054603], Kit Carson, CO

-

(4) SPRINGFIELD 7 WSW [USC00057866], Springfield, CO

-

(5) GREELEY UNC [USC00053553], Greeley, CO

-

(6) LIMON WSMO [USW00093010], Limon, CO

-

(7) BRIGGSDALE [USC00050945], Briggsdale, CO

-

(8) NUNN [USC00056023], Nunn, CO

-

(9) BRIGHTON 3 SE [USC00050950], Brighton, CO

-

(10) BYERS 5 ENE [USC00051179], Byers, CO

-

(11) CHEYENNE WELLS [USC00051564], Cheyenne Wells, CO

Influencing water features

There are no water features that influence the vegetation or management of the site.

Soil features

The soils on this site are very deep, well drained soils that formed from slope alluvium. They typically have a moderate to moderately rapid permeability class. The available water capacity is typically moderate, but ranges from low to high. Available water is the portion of water in a soil that can be readily absorbed by plant roots. This is the amount of water released between the field capacity and the permanent wilting point. As fineness of texture increases, there is a general increase in available moisture storage from sands to loams and silt loams. The soil moisture regime is typically aridic ustic. The soil temperature regime is mesic.

The surface layer of the soils in this site are typically loam or silt loam. The surface layer ranges from a depth of 4 to 7 inches thick. The subsoil and underlying material have a similar range in texture as the surface layer. Soils in this site typically have free carbonates at the surface, but some soils may be leached to 10 inches. These soils are susceptible to erosion by water and wind. The potential for water erosion accelerates with increasing slope.

Surface soil structure is typically granular, and structure below the surface is subangular blocky to massive. Soil structure describes the manner in which soil particles are aggregated and defines the nature of the system of pores and channels in a soil. Together, soil texture and structure help determine the ability of the soil to hold and conduct the water and air necessary for sustaining life.

Major soil series correlated to this ecological site include: Mitchell.

Other soil series that have been correlated to this site, but may eventually be re-correlated include: Keota.

Note: Revisions to soil surveys are on-going. For the most recent updates, visit the Web Soil Survey, the official site for soils information: http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/WebSoilSurvey.aspx.

The attributes listed below represent 0-40 inches in depth or to the first restrictive layer.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Loam (2) Silt loam |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate to moderately rapid |

| Soil depth | 203 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

12.7 – 30.48 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 15% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

7.4 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 2% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0% |

Ecological dynamics

The information in this ESD, including the state-and-transition model diagram (STM), was developed using archeological and historical data, professional experience, and scientific studies. The information is representative of a dynamic set of plant communities that represent the complex interaction of several ecological processes. The plant composition has been determined by study of rangeland relic areas, areas protected from excessive disturbance, seasonal use pastures, short duration or time-controlled grazing strategies, and historical accounts.

The degree of grazing has a significant impact on the ecological dynamics of the site. This region was historically occupied by large grazing animals, such as bison, elk, pronghorn, and mule deer. Grazing by these large herbivores, along with climatic and seasonal weather fluctuations, had a major influence on the ecological dynamics of the site. Deer and pronghorn are widely distributed throughout the MLRA. Secondary influences of herbivory by species such as prairie dogs and other small rodents, insects, and root-feeding organisms continues to impact the vegetation.

Historically, grazing patterns by herds of large ungulates were driven by water distribution, precipitation events, drought events, and fire. It is believed that grazing periods would have been shorter, followed by longer recovery periods. These large migrating herds impacted the ecological processes of nutrient and hydrologic cycles, by urination, trampling (incorporation of litter into the soil surface), and breaking of surface crust, (which increases water infiltration).

Today, livestock grazing, especially beef cattle has been a major influence on the ecological dynamics of the site. Grazing management, coupled with the effects of annual climatic variations, largely dictates the plant communities for the site.

Recurrent drought has historically impacted the vegetation of this region. Changes in species composition vary depending upon the duration and severity of the drought cycle and prior grazing management. Drought events since 2002 have significantly increased mortality of blue grama and buffalograss in some locales.

This site developed with occasional fire as part of the ecological processes. Historic fire frequency (pre-industrial) is estimated at 10 to14 years (Guyette, 2012), randomly distributed, and started by lightning at various times throughout the growing season. Early human inhabitants also were likely to start fires for various reasons (deliberate or accidental). It is believed that fires were set as a management tool for attracting herds of large migratory herbivores (Stewart, 2002). The impact of fire over the past 100 years has been relatively insignificant due to the human control of wildfires and the lack of acceptance of prescribed fire as a management tool.

Mechanical treatment consisting of contour pitting, furrowing, terracing, chiseling, and disking has been practiced in the past. It was theorized that the use of this high-input technology would improve production and plant composition on rangeland. These high-cost practices have shown to have no significant long-term benefits on production or plant composition and have only resulted in a permanently rough ground surface. Prescribed grazing that mimics the historic grazing of herds of migratory herbivores, as described earlier, has been shown to result in desired improvements based on management goals for this ecological site.

Eastern Colorado was strongly affected by extended drought conditions in the “Dust Bowl” period of the 1930’s, with recurrent drought cycles in the 1950s and 1970s. Extreme to exceptional drought conditions have re-visited the area from 2002 to 2012, with brief interludes of near normal to normal precipitation years. Long-term effects of these latest drought events have yet to be determined. Growth of native cool-season plants begins about April 1 and continues to mid-June. Native warm-season plants begin growth about May 1 and continue to about August 15. Regrowth of cool-season plants occurs in September in most years, depending on the availability of moisture.

Grazing by large herbivores, without adequate recovery periods causes western wheatgrass and green needlegrass to decrease, and blue grama and buffalograss to increase. Blue grama and buffalograss may eventually form a sod-like appearance. Fourwing saltbush and winterfat decrease in frequency and production. American vetch and other highly palatable forbs also decrease. Fendler threeawn, annuals, and bare ground increase under heavy, continuous grazing, excessive defoliation, or long-term non-use. Areas of this ecological site have been tilled and used for crop production, and converted to suburban residence and small acreages, especially near the larger communities.

The Siltstone Plains Ecological Site is characterized by four states: Reference, Warm-Season Shortgrass, Increased Bare Ground, and Tilled. The Reference State is characterized by cool-season midgrass (western wheatgrass, green needlegrass) and warm-season bunchgrass (blue grama). The Warm-season Shortgrass State is characterized by a warm-season short bunchgrass (blue grama) and stoloniferous grass (buffalograss). The Increased Bare Ground State is characterized by early successional warm-season bunchgrass (Fendler threeawn), cool-season short bunchgrass (squirreltail), annual grasses, and annual forbs. The Tilled State has been mechanically disturbed by equipment and includes either a variety of reseeded warm and cool-season grasses (Seeded Community) or early successional plants as well as annual grasses and forbs (Go-Back Community).

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

| T1A | - | Excessive grazing. Lack of fire. |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Tillage. |

| T2A | - | Excessive grazing. Lack of fire. |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

| 1.1A | - | Excessive grazing. Lack of fire. |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1B | - | Non-use. Lack of fire. |

| 1.2A | - | Prescribed grazing. Prescribed fire. |

| 1.3A | - | Prescribed grazing. Prescribed fire. |

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference

The Reference state is characterized by three plant communities. The plant communities and various successional stages between them represent the natural range of variability due to the disturbance regimes that occur on the site.

Dominant plant species

-

fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens), shrub

-

winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata), shrub

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

Community 1.1

Western Wheatgrass and Blue Grama

This is the interpretive plant community. This plant community evolved with grazing by large herbivores, is well suited for grazing by domestic livestock, and can be found on areas that are properly managed with prescribed grazing. The reference plant community consists mainly of cool-season mid grasses and warm-season short grasses. The principal mid grasses are western wheatgrass and green needlegrass. Blue grama is the dominant shortgrass. Grasses and grass-likes of secondary importance are buffalograss, needle and thread, Indian ricegrass, little bluestem, prairie junegrass, and sun sedge. Major forbs and shrubs include American vetch, scarlet globemallow, dotted gayfeather, fourwing saltbush, and winterfat. The reference plant community is about 70-85 percent grasses and grass-likes, 5-15 percent forbs and 10-15 percent shrubs by air-dry weight. This is a sustainable plant community in terms of soil stability, watershed function, and biological integrity. Litter is properly distributed with little movement. Decadence and natural plant mortality is very low. Community dynamics, nutrient cycle, water cycle, and energy flow are functioning properly. This community is resistant to many disturbances except excessive grazing, tillage, and development into urban or other uses. Total annual production, during an average year, ranges from 500 to 1,700 pounds per acre air-dry weight and averages 1,200 pounds. These production figures are the fluctuations expected during favorable, normal, and unfavorable years.

Dominant plant species

-

fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens), shrub

-

winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata), shrub

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

Figure 9. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 370 | 1054 | 1491 |

| Forb | 62 | 135 | 207 |

| Shrub/Vine | 129 | 157 | 207 |

| Total | 561 | 1346 | 1905 |

Figure 10. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). CO6701, Cool-season/warm-season codominant; MLRA-67B; upland fine-textured soils..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 20 | 28 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Community 1.2

Blue Grama and Western Wheatgrass

Key species such as green needlegrass, western wheatgrass, American vetch, fourwing saltbush, and winterfat have been reduced. Blue grama and buffalograss have increased in abundance, and are beginning to take on a sod appearance. Sand dropseed, purple threeawn, sixweeks fescue, bottlebrush squirreltail, and hairy goldaster have also increased. This plant community is at risk of losing green needlegrass, western wheatgrass, American vetch, fourwing saltbush, and winterfat. Once these key species are completely removed and other plants have increased, it will take a long time to bring them back by management alone. Substantial increases in money and other resources will be required to replace the lost species in a shorter period of time. Total aboveground carbon has been reduced due to decreases in forage and litter production. Loss of rhizomatous wheatgrass, nitrogen fixing forbs, the shrub component, and increased warm-season short grasses has begun to alter the biotic integrity of this community. Water and nutrient cycles are at risk of becoming impaired. Total annual production, during an average year, ranges from 200 to 1,100 pounds per acre air-dry weight and averages 800 pounds.

Dominant plant species

-

fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens), shrub

-

winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata), shrub

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

Figure 11. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). CO6702, Warm-season dominant, cool-season subdominant; MLRA-67B, upland fine textured soils..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 45 | 20 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Community 1.3

Western Wheatgrass and Blue Grama, Low Plant Density

This plant community occurs when grazing is removed for long periods of time in the absence of fire. Plant composition is similar to the reference plant community, however, individual species production and frequency will be lower. Much of the nutrients are tied up in standing dead canopy and increased litter. The semiarid environment and the absence of animal traffic to break down litter slow nutrient recycling. Increased standing dead canopy limits sunlight from reaching plant crowns. Many plants, especially bunchgrasses (green needlegrass, blue grama), exhibit increased mortality. Increased litter and absence of grazing animals reduces seed germination and establishment. In advanced stages, plant mortality can increase and erosion may eventually occur if bare ground increases. Once this happens it will require increased energy input in terms of practice cost and management to bring back. Total annual production ranges from 300 to 1,300 pounds per acre air-dry weight and averages 850 pounds during an average year.

Dominant plant species

-

fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens), shrub

-

winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata), shrub

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

Figure 12. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). CO6703, Cool-season/warm-season codominant, excess litter; MLRA-67B; upland fine textured soils..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Excessive grazing and reduced fire frequency shifts this plant community to the 1.2 community. Recurring spring seasonal grazing will decrease cool-season plants. Recurring summer grazing decreases warm-season plants and tends to increase cool-season plants over time.

Pathway 1.1B

Community 1.1 to 1.3

Non-use and lack of fire moves this community to the 1.3 community. Plant decadence and standing dead plant material impede energy flow.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Grazing with adequate recovery periods, proper stocking, and prescribed fire return this plant community back to the reference community.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.1

The return of grazing with adequate recovery periods and normal fire frequency facilitate recovery to the reference plant community. This change can occur in a relatively short time frame.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 2

Warm Season Shortgrass

This state is characterized by a vegetation shift to a shortgrass dominated community. An ecological threshold has been crossed and a significant amount of production and diversity has been lost when compared to the Reference state. Significant biotic and edaphic (soil characteristic) changes have negatively impacted energy flow and nutrient and hydrologic cycles. This is a very stable state, resistant to change due to the high tolerance of blue grama and buffalograss to grazing. The loss of other functional/structural groups such as cool-season midgrasses, forbs, and shrubs, reduces the biodiversity and productivity of this site.

Dominant plant species

-

broom snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae), shrub

-

soapweed yucca (Yucca glauca), shrub

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

-

buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides), grass

Community 2.1

Blue Grama and Buffalograss

Most of the key grass, forb, and shrub species are absent. Western wheatgrass may persist in trace amounts, though greatly reduced in vigor and not readily seen. Blue grama and buffalograss dominate the community with a tight “sodbound” appearance. Purple threeawn, sand dropseed, sixweeks fescue, and hairy goldaster have increased. This plant community is resistant to change due to grazing tolerance of buffalograss and blue grama. A significant amount of production and diversity has been lost from this community when compared to the reference plant community. Loss or major reduction of cool-season grasses, shrub component, and nitrogen fixing forbs have negatively impacted energy flow and nutrient cycling. Water infiltration is reduced significantly due to the massive shallow root system “root pan”, characteristic of blue grama and buffalograss. Soil loss may be obvious where flow paths are connected. Production ranges from 100 to 800 pounds of air-dry vegetation per acre per year and averages 600 pounds.

Dominant plant species

-

broom snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae), shrub

-

soapweed yucca (Yucca glauca), shrub

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

-

buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides), grass

Figure 13. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). CO6707, Warm-season dominant; MLRA-67B; upland fine-textured soils..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 45 | 20 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

State 3

Increased Bare Ground

Litter levels are extremely low. Erosion is evident and flow paths are continuous. Rills may occur on steeper slopes. Wind scoured areas may be apparent on knolls or unprotected areas. The nutrient cycle, water cycle, and overall energy flow are greatly impaired. Organic matter and carbon reserves are greatly reduced.

Dominant plant species

-

broom snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae), shrub

-

soapweed yucca (Yucca glauca), shrub

-

Fendler threeawn (Aristida purpurea var. longiseta), grass

-

ring muhly (Muhlenbergia torreyi), grass

Community 3.1

Purple Threeawn, Increased Bare Ground

This plant community develops with excessive defoliation and lack of fire. Purple threeawn is the dominant species. Blue grama may persist in localized areas. Introduced annuals such as burningbush and Russian thistle are present. Introduced species such as field bindweed can also be present, especially on prairie dog towns. Total annual production can vary from 50 to 200 pounds of air-dry vegetation per acre and averages 100 pounds during a normal year.

Dominant plant species

-

broom snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae), shrub

-

soapweed yucca (Yucca glauca), shrub

-

Fendler threeawn (Aristida purpurea var. longiseta), grass

-

Russian thistle (Salsola), other herbaceous

-

burningbush (Bassia scoparia), other herbaceous

Figure 14. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). CO6707, Warm-season dominant; MLRA-67B; upland fine-textured soils..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 45 | 20 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

State 4

Tilled

The Tilled state is the result of the site being tilled (farmed). An ecological threshold has been crossed due to complete removal of vegetation and years of soil tillage. Physical, chemical, and biological soil properties have been dramatically altered.

Dominant plant species

-

cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), grass

-

Fendler threeawn (Aristida purpurea var. longiseta), grass

-

Russian thistle (Salsola), other herbaceous

-

burningbush (Bassia scoparia), other herbaceous

Community 4.1

Cheatgrass and Purple Threeawn, Go-Back Land

Go-back land occurs where the soil has been tilled and abandoned. All native plants have been eliminated and the soil structure degraded. A plowpan or compacted layer is formed. Residual synthetic chemicals often remain from past farming operations and erosion processes are active. Over time, early successional annuals and perennials begin to cover the soil surface. Burningbush, Russian thistle, and cheatgrass are examples of some early annuals which begin to establish. These areas will soon become dominated by purple threeawn. Eventually, sand dropseed, and ring muhly, will begin to establish. Organic matter has left the system through decomposition and erosion. Erosion can be accelerated if ground cover is lacking. In some instances, when this soil is tilled and abandoned, secondary succession leads to an Indian ricegrass dominated plant community.

Dominant plant species

-

cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), grass

-

Fendler threeawn (Aristida purpurea var. longiseta), grass

-

Russian thistle (Salsola), other herbaceous

-

burningbush (Bassia scoparia), other herbaceous

Community 4.2

Seeded

This community results from tillage and is seeded to adapted native plant species. A seed mixture of grasses, forbs, and shrubs can be used to accomplish various management objectives. This plant community can vary considerably.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Excessive grazing and lack of fire shifts this state across an ecological threshold to the Warm-season Shortgrass Dominant State.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 4

Tillage of this ecological site will cause an immediate transition across an ecological threshold to the Tilled State. This transition can occur from any plant community and is irreversible.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Long-term, excessive grazing and lack of fire shifts this state to the Increased Bare Ground State. Erosion and loss of organic matter and carbon reserves are concerns.

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | 942–1143 | |||||

| western wheatgrass | PASM | Pascopyrum smithii | 336–471 | – | ||

| blue grama | BOGR2 | Bouteloua gracilis | 336–404 | – | ||

| green needlegrass | NAVI4 | Nassella viridula | 202–269 | – | ||

| buffalograss | BODA2 | Bouteloua dactyloides | 13–67 | – | ||

| Grass, perennial | 2GP | Grass, perennial | 13–67 | – | ||

| sun sedge | CAINH2 | Carex inops ssp. heliophila | 13–40 | – | ||

| needle and thread | HECOC8 | Hesperostipa comata ssp. comata | 13–27 | – | ||

| sand dropseed | SPCR | Sporobolus cryptandrus | 13–27 | – | ||

| sixweeks fescue | VUOC | Vulpia octoflora | 0–13 | – | ||

| prairie Junegrass | KOMA | Koeleria macrantha | 0–13 | – | ||

| ring muhly | MUTO2 | Muhlenbergia torreyi | 0–13 | – | ||

| squirreltail | ELELE | Elymus elymoides ssp. elymoides | 0–13 | – | ||

| Indian ricegrass | ACHY | Achnatherum hymenoides | 0–13 | – | ||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 0–13 | – | ||

| needleleaf sedge | CADU6 | Carex duriuscula | 0–13 | – | ||

| tumblegrass | SCPA | Schedonnardus paniculatus | 0–13 | – | ||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | 0–13 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 2 | 67–202 | |||||

| American vetch | VIAM | Vicia americana | 13–67 | – | ||

| Forb, perennial | 2FP | Forb, perennial | 13–67 | – | ||

| purple prairie clover | DAPU5 | Dalea purpurea | 13–27 | – | ||

| lacy tansyaster | MAPIP4 | Machaeranthera pinnatifida ssp. pinnatifida var. pinnatifida | 13–27 | – | ||

| scarlet globemallow | SPCO | Sphaeralcea coccinea | 13–27 | – | ||

| white heath aster | SYER | Symphyotrichum ericoides | 0–13 | – | ||

| largeflower Townsend daisy | TOGR | Townsendia grandiflora | 0–13 | – | ||

| crownleaf evening primrose | OECO2 | Oenothera coronopifolia | 0–13 | – | ||

| purple locoweed | OXLA3 | Oxytropis lambertii | 0–13 | – | ||

| New Mexico groundsel | PANEM | Packera neomexicana var. mutabilis | 0–13 | – | ||

| woolly plantain | PLPA2 | Plantago patagonica | 0–13 | – | ||

| slimflower scurfpea | PSTE5 | Psoralidium tenuiflorum | 0–13 | – | ||

| upright prairie coneflower | RACO3 | Ratibida columnifera | 0–13 | – | ||

| threadleaf ragwort | SEFLF | Senecio flaccidus var. flaccidus | 0–13 | – | ||

| hairy false goldenaster | HEVI4 | Heterotheca villosa | 0–13 | – | ||

| dotted blazing star | LIPU | Liatris punctata | 0–13 | – | ||

| fernleaf biscuitroot | LODI | Lomatium dissectum | 0–13 | – | ||

| rush skeletonplant | LYJU | Lygodesmia juncea | 0–13 | – | ||

| textile onion | ALTE | Allium textile | 0–13 | – | ||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 0–13 | – | ||

| tarragon | ARDR4 | Artemisia dracunculus | 0–13 | – | ||

| twogrooved milkvetch | ASBI2 | Astragalus bisulcatus | 0–13 | – | ||

| woolly locoweed | ASMO7 | Astragalus mollissimus | 0–13 | – | ||

| wavyleaf thistle | CIUN | Cirsium undulatum | 0–13 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 3 | 135–202 | |||||

| fourwing saltbush | ATCA2 | Atriplex canescens | 135–202 | – | ||

| winterfat | KRLA2 | Krascheninnikovia lanata | 27–94 | – | ||

| Shrub (>.5m) | 2SHRUB | Shrub (>.5m) | 13–40 | – | ||

| prairie sagewort | ARFR4 | Artemisia frigida | 0–13 | – | ||

| soapweed yucca | YUGL | Yucca glauca | 0–13 | – | ||

| spreading buckwheat | EREF | Eriogonum effusum | 0–13 | – | ||

| rubber rabbitbrush | ERNAN5 | Ericameria nauseosa ssp. nauseosa var. nauseosa | 0–13 | – | ||

| spinystar | ESVIV | Escobaria vivipara var. vivipara | 0–13 | – | ||

| broom snakeweed | GUSA2 | Gutierrezia sarothrae | 0–13 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

WILDLIFE INTERPRETATIONS:

The variety of grasses, forbs, and shrubs on this ecological site in the various plant communities provides habitat for a wide range of wildlife species. Historic large grazers that influenced these plant communities were bison, elk, and pronghorn. Changes over time have resulted in the loss of bison, the reduction in elk numbers, and pronghorn population swings. Domestic grazers now share these habitats with wildlife. The grassland communities of eastern Colorado are home to many bird species. Changes in the composition of the plant community when moving from the reference plant community to other communities on this ecological site may result in dramatic species shifts in the bird community. Because of a lack of permanent water, fish and many amphibians are not expected on this ecological site. Mule and white-tailed deer may use this ecological site, however the shrub cover is too low to expect more than occasional use. The gray wolf and wild bison used this ecological site in historic times. The wolf is thought to be extirpated from Eastern Colorado. Bison in the area are domesticated.

1.1 Reference Plant Community

Prairie dogs support a high amount of wildlife diversity for their now reduced acreage. Species such as ferruginous hawks, burrowing owls, mountain plovers, western rattlesnake, and black-footed ferret occur in association with prairie dog towns.

Pronghorns are the most abundant ungulate on this site, followed by mule deer. This site also supports a high diversity of migratory grassland birds including grasshopper sparrow, McCown's longspur, chestnut-collared longspur, and loggerheaded shrike among others. The loamier soils support many reptile species that may use the site to meet all or parts of their life requisites. Pollinating insects are attracted to the forbs expected in this plant community. Various species of beetles and grasshoppers are also present.

1.2 Community

This community is very similar to the reference community; therefore the value for wildlife is not significantly different. Wildlife species using this this plant community would be the same.

1.3 Community

The wildlife species found here, will be similar to those in the reference community.

2.1 Community

This community has reduced wildlife species diversity due to the loss of taller structure grasses and shrubs and reduced forb diversity. Pronghorns and swift fox continue to use this community. Grassland songbird species that need taller structure like grasshopper sparrows are absent, but short-structure species like horned lark and longspurs will be present. If prairie dogs are present, ferruginous hawks, burrowing owls, and mountain plover may occur.

3.1 Community

The loss of perennial forbs, combined with the increase in bare ground will result in a change in wildlife species when compared with the reference plant community. Western rattlesnake and other reptiles are still be found here. Swainson’s hawks continue to be found here as it is easy to spot prey in this community. Black-tailed prairie dogs and their obligate species are also present.

4.1 Community

The wildlife species found here will be similar to the 3.1 community.

4.2 Community (Adapted Seed Mixes)

Wildlife use of tilled and replanted fields is dependent on the plant species used in the planted seed mix. Many of these sites currently support plains sharp-tailed grouse, ring-necked pheasant, grasshopper sparrow, and other upland bird species. Purpose of the seeding determines the usability for wildlife. If wildlife use is a primary concern, then seed mixes must be formulated to meet species specific habitat requirements.

GRAZING INTERPRETATIONS:

The following table lists suggested initial stocking rates for an animal unit (1000-pound beef cow) under continuous grazing (yearlong grazing or growing-season-long grazing) based on normal growing conditions. However, continuous grazing is not recommended. These estimates should only be used as preliminary guidelines in the initial stages of the conservation planning process. Often, the existing plant composition does not entirely match any particular plant community described in this ecological site description. Therefore, field inventories are always recommended to document plant composition, total production, and palatable forage production. Carrying capacity estimates that reflect on-site conditions should be calculated using field inventories.

If the following production estimates are used, they should be adjusted based on animal kind or class and on the specific palatability of the forage plants in the various plant community descriptions. Under a properly stocked, properly applied, prescribed grazing management system that provides adequate recovery periods following each grazing event, improved harvest efficiencies eventually result in increased carrying capacity. See USDA-NRCS Colorado Prescribed Grazing Standard and Specification Guide (528).

The stocking rate calculations are based on the total annual forage production in a normal year multiplied by 25 percent harvest efficiency divided by 912.5 pounds of ingested air-dry vegetation for an animal unit per month (AUM).

Plant Community (PC) Production (lbs./acre) and Stocking Rate (AUM/acre)

Reference PC - (1200) (0.33)

1.2 PC - (800) (0.22)

2.1 PC - (600) (0.16)

1.3 PC - (850) (*)

All stocking rates for grazing plans should be determined on-site.

Grazing by domestic livestock is one of the major income-producing industries in the area. Rangelands in this area provide yearlong forage under prescribed grazing for cattle, sheep, horses, and other herbivores.

Hydrological functions

Water is the principal factor limiting forage production on this site. This site is dominated by soils in hydrologic group B. Infiltration and runoff potential for this site varies from moderate to high depending on ground cover. In many cases, areas with greater than 75 percent ground cover have the greatest potential for high infiltration and lower runoff. An example of an exception would be where short grasses form a strong sod and dominate the site. Areas where ground cover is less than 50 percent have the greatest potential to have reduced infiltration and higher runoff (refer to NRCS Section 4, National Engineering Handbook (USDA–NRCS, 1972–2012) for runoff quantities and hydrologic curves).

Recreational uses

This site provides hunting, hiking, photography, bird watching, and other opportunities. The wide varieties of plants that bloom from spring until fall have an aesthetic value that appeals to visitors.

Wood products

No appreciable wood products are present on the site.

Other products

Site Development and Testing Plan

General Data (MLRA and Revision Notes, Hierarchical Classification, Ecological Site Concept, Physiographic, Climate, and Water Features, and Soils Data):

Updated. All “Required” items complete to Provisional level.

Community Phase Data (Ecological Dynamics, STM, Transition & Recovery Pathways, Reference Plant Community, Species Composition List, Annual Production Table):

Updated. All “Required” items complete to Provisional level.

NOTE: Annual Production Table is from the “Previously Approved” ESD 2004. The Species Composition List is also from the 2004 version, with minor edits. These will need review for future updates at Approved level.

Each Alternative State/Community:

Complete to Provisional level

Supporting Information (Site Interpretations, Assoc. & Similar Sites, Inventory Data References, Agency/State Correlation, References):

Updated. All “Required” items complete to Provisional level.

Livestock Interpretations updated to reflect Total Annual Production revisions in each plant community.

Wildlife interpretations, general narrative, and individual plant communities updated to the Provisional level. Hydrology, Recreational Uses, Wood Products, Other Products, Plant Preferences table, and Rangeland Health Reference Sheet carried over from previously “Approved” ESD 2004.

Reference Sheet

The Reference Sheet was previously approved in 2007.

It will be updated at the next “Approved” level.

“Future work, as described in a project plan, to validate the information in this provisional ecological site description is needed. This will include field activities to collect low and medium intensity sampling, soil correlations, and analysis of that data. Annual field reviews should be done by soil scientists and vegetation specialists. A final field review, peer review, quality control, and quality assurance reviews of the ESD will be needed to produce the final document.” (NI 430_306 ESI and ESD, April, 2015)

Other information

Relationship to Other Hierarchical Classifications:

NRCS Classification Hierarchy:

Physiographic Divisions of the United States (Fenneman, 1946): Physiographic DivisionPhysiographic ProvincePhysiographic SectionLand Resource RegionMajor Land Resource Area (MLRA)Land Resource Unit (LRU).

USFS Classification Hierarchy:

National Hierarchical Framework of Ecological Units (Cleland et al, 181-200):

DomainDivisionProvinceSectionSubsectionLandtype Association LandtypeLandtype Phase.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

NRI: references to Natural Resource Inventory data

Information presented here has been derived from data collection on private and federal lands using:

• Double Sampling (clipped 2 of 5 plots)*

• Rangeland Health (Pellant et al., 2005)

• Soil Stability (Pellant et al., 2005)

• Line Point Intercept : Foliar canopy, basal cover (Forb, Graminoid, Shrub, subshrub, Lichen, Moss, Rock fragments, bare ground, percent Litter) (Herrick et al., 2005)

• Soil pedon descriptions collected on site (Schoeneberger et al., 2012)

*NRCS double-sampling method, CO NRCS Similarity Index Worksheet 528(1).

Additional reconnaissance data collection using numerous ocular estimates and other inventory data; NRCS clipping data for USDA program support; Field observations from experienced range trained personnel. Specific data information is contained in individual landowner/user case files and other files located in county NRCS field offices.

References

-

Guyette, R.P., M.C. Stambaugh, D.C. Dey, and R. Muzika. 2012. Predicting Fire Frequency with Chemistry and Climate. Ecosystems 15:322–335.

Other references

Data collection for this ecological site was done in conjunction with the progressive soil surveys within the 67B Central High Plains (Southern Part) of Colorado. It has been mapped and correlated with soils in the following soil surveys: Adams County, Arapahoe County, Baca County, Bent County, Boulder County, Cheyenne County, El Paso County Area, Elbert County, Eastern Part, Kiowa County, Kit Carson County, Larimer County Area, Las Animas County Area, Lincoln County, Logan County, Morgan County, Prowers County, Washington County, Weld County, Northern Part, and Weld County, Southern Part.

30 Year Climatic and Hydrologic Normals (1981-2010) Reports. National Water and climate Center: Portland, OR. August 2015

ACIS-USDA Field Office Climate Data (WETS), period of record 1971-2000 http://agacis.rcc-acis.org (powered by WRCC) Accessed March 2016

Andrews, R. and R. Righter. 1992. Colorado Birds. Denver Museum of Natural History, Denver, CO. 442

Armstrong, D.M. 1972. Distribution of mammals in Colorado. Univ. Kansas Museum Natural History Monograph #3. 415.

Butler, LD., J.B. Cropper, R.H. Johnson, A.J. Norman, G.L. Peacock, P.L. Shaver, and K.E. Spaeth. 1997, revised 2003. National Range and Pasture Handbook. National Cartography and Geospatial Center’s Technical Publishing Team: Fort Worth, TX. http://www.glti.nrcs.usda.gov/technical/publications/nrph.html Accessed August 2015

Clark, J., E. Grimm, J. Donovan, S. Fritz, D. Engrstom, and J. Almendinger. 2002. Drought cycles and landscape responses to past Aridity on prairies of the Northern Great Plains, USA. Ecology, 83(3), 595-601.

Cleland, D., P. Avers, W.H. McNab, M. Jensen, R. Bailey, T. King, and W. Russell. 1997. National Hierarchical Framework of Ecological Units, published in Ecosystem Management: Applications for Sustainable Forest and Wildlife Resources, Yale University Press

Cooperative climatological data summaries. NOAA. Western Regional Climate Center: Reno, NV. Web. http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/climatedata/climsum Accessed August 2015

Egan, Timothy. 2006. The Worst Hard Time. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company: New York, NY.

Fitzgerald, J.P., C.A. Meaney, and D.M. Armstrong. 1994. Mammals of Colorado. Denver Museum of Natural History, Denver, CO. 467. Hammerson, G.A. 1986. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. CO Div. Wild. Publication Code DOW-M-I-3-86. 131.

Herrick, Jeffrey E., J.W. Van Zee, K.M. Haystad, L.M. Burkett, and W.G. Witford. 2005. Monitoring Manual for Grassland, Shrubland, and Savanna Ecosystems, Volume II. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Jornada Experimental Range, Las Cruces, N.M.

Kingery, H., Ed. (1998) Colorado Breeding Birds Atlas. Dist. CO Wildlife Heritage Foundation: Denver, CO. 636.

National Water & Climate Center. USDA-NRCS. USDA Pacific Northwest Climate Hub: Portland, OR. http://www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov/ Accessed March 2016

National Weather Service Co-op Program. 2010. Colorado Climate Center. Colorado State Univ. Web. http://climate.atmos.colostate.edu/dataaccess.php March 2016

Pellant, M., P. Shaver, D.A. Pyke, J.E. Herrick. (2005) Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health, Version 4. BLM National Business Center Printed Materials Distribution Service: Denver, CO.

PLANTS Database. 2015. USDA-NRCS. Web. http://plants.usda.gov/java/ Accessed August 2015. February 2016

PRISM Climate Data. 2015. Prism Climate Group. Oregon State Univ. Corvallis, OR. http://www.prism.oregonstate.edu/ Accessed August 2015.

Rennicke, J. 1990. Colorado Wildlife. Falcon Press, Helena and Billings, MT and CO Div. Wildlife, Denver CO. 138.

Schoeneberger, P.J., D.A. Wysockie, E.C. Benham, and Soil Survey Staff. 2012. Field book for describing and sampling soils, Version 3.0. Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Soil Survey Center: Lincoln, NE.

The Denver Posse of Westerners. 1999. The Cherokee Trail: Bent’s Old Fort to Fort Bridger. The Denver Posse of Westerners, Inc. Johnson Printing: Boulder, CO

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. September 1991. Changes in Vegetation and Land Use I eastern Colorado, A Photographic study, 1904-1986.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2006. Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. US Department of Agriculture Handbook 296.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. National Geospatial Center of Excellence. Colorado annual Precipitation Map from 1981-2010, Annual Average Precipitation by State

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2009. Part 630, Hydrology, National Engineering Handbook

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 1972-2012. National Engineering Handbook Hydrology Chapters. http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detailfull/national/water/?&cid=stelprdb1043063 Accessed August 2015.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. National Soil Survey Handbook title 430-VI. http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/ref/?cid=nrcs142p2_054242 Accessed July 2015

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Soil Survey Division Staff. 1993. Soil Survey Manual.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture.1973. Soil Survey of Baca County, Colorado.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. 1970. Soil Survey of Bent County, Colorado.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. 1968. Soil Survey of Crowley County, Colorado.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. 1981 Soil Survey of El Paso County Area, Colorado.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. 1995. Soil Survey of Fremont County Area, Colorado.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. 1983. Soil Survey of Huerfano County Area, Colorado.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture.1981. Soil Survey of Kiowa County, Colorado.

Western Regional Climate Center. 2022. Climate of Colorado, climate of the eastern plains. https://wrcc.dri.edu/Climate/narrative_co.php (accessed 9 August 2022).

Additional Literature:

Clark, J., E. Grimm, J. Donovan, S. Fritz, D. Engrstom, and J. Almendinger. 2002. Drought cycles and landscape responses to past Aridity on prairies of the Northern Great Plains, USA. Ecology, 83(3), 595-601.

Collins, S. and S. Barber. (1985). Effects of disturbance on diversity in mixed-grass prairie. Vegetation, 64, 87-94.

Egan, Timothy. 2006. The Worst Hard Time. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company: New York, NY.

Hart, R. and J. Hart. 1997. Rangelands of the Great Plains before European Settlement. Rangelands, 19(1), 4-11.

Hart, R. 2001. Plant biodiversity on shortgrass steppe after 55 years of zero, light, moderate, or heavy cattle grazing. Plant Ecology, 155, 111-118.

Heitschmidt, Rodney K., J.W. Stuth, (edited by). 1991. Grazing Management, an Ecological Perspective. Timberland Press, Portland, OR.

Jackson, D. 1966. The Journals of Zebulon Montgomery Pike with letters & related documents. Univ. of Oklahoma Press, First edition: Norman, OK.

Mack, Richard N., and J.N. Thompson. 1982. Evolution in Steppe with Few Large, Hooved Mammals. The American Naturalist. 119, No. 6, 757-773.

Reyes-Fox, M., Stelzer H., Trlica M.J., McMaster, G.S., Andales, A.A., LeCain, D.R., and Morgan J.A. 2014. Elevated CO2 further lengthens growing season under warming conditions. Nature, April 23 2014.Available online. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v510/n7504/full/nature13207.html, accessed March 2017.

Stahl, David W., E.R. Cook, M.K. Cleaveland, M.D. Therrell, D.M. Meko, H.D. Grissino-Mayer, E. Watson, and B.H. Luckman. Tree-ring data document 16th century megadrought over North America. 2000. Eos, 81(12), 121-125.

The Denver Posse of Westerners. 1999. The Cherokee Trail: Bent’s Old Fort to Fort Bridger. The Denver Posse of Westerners, Inc. Johnson Printing: Boulder, CO.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. 2004. Vascular plant species of the Comanche National Grasslands in southeastern Colorado. US Forest Service. Rocky Mountain Research Station. Fort Collins, CO.

Zelikova, Tamara Jane, D.M. Blumenthal, D.G. Williams, L. Souza, D.R. LeCain, J.Morgan. 2014. Long-term Exposure to Elevated CO2 Enhances Plant Community Stability by Suppressing Dominant Plant Species in a Mixed-Grass Prairie. Ecology, 2014 issue. Available online. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1414659111

Contributors

Kimberly Diller, Ecological Site Specialist, NRCS MLRA, Pueblo SSO

Andy Steinert, MLRA 67B Soil Survey Leader, NRCS MLRA Fort Morgan SSO

Ben Berlinger, Rangeland Management Specialist, Retired NRCS La Junta, CO

Doug Whisenhunt, Ecological Site Specialist, NRCS MLRA, Pueblo SSO

Approval

Kirt Walstad, 12/05/2024

Acknowledgments

Program Support:

Rachel Murph, NRCS State Rangeland Management Specialist-QC, Denver, CO

David Kraft, NRCS MLRA Ecological Site Specialist-QA, Emporia, KS

Josh Saunders, Rangeland Management Specialist-QC, NRCS Fort Morgan, CO

Patty Knupp, Biologist, Area 3, NRCS Pueblo, CO

Noe Marymor, Biologist, Area 2, NRCS Greeley, CO

Richard Mullaney, Resource Conservationist, Retired, NRCS, Akron, CO

Chad Remley, Regional Director, N. Great Plains Soil Survey, Salina, KS

B.J. Shoup, State Soil Scientist, Denver

Eugene Backhaus, State Resource Conservationist, Denver

Carla Green Adams, Editor, NRCS, Denver, CO

Partners/Contributors:

Rob Alexander, Agricultural Resources, Boulder Parks & Open Space, Boulder, CO

David Augustine, Research Ecologist, Agricultural Research Service, Fort Collins, CO

John Fusaro, Rangeland Management Specialist, NRCS, Fort Collins, CO

Jeff Goats, Resource Soil Scientist, NRCS, Pueblo, CO

Clark Harshbarger, Resource Soil Scientist, NRCS, Greeley, CO

Mike Moore, Soil Scientist, NRCS MLRA Fort Morgan SSO

Tom Nadgwick, Rangeland Management Specialist, NRCS, Akron CO

Dan Nosal, Rangeland Management Specialist, NRCS, Franktown, CO

Steve Olson, Botanist, USFS, Pueblo, CO

Randy Reichert, Rangeland Specialist, Retired, USFS, Nunn, CO

Don Schoderbeck, Range Specialist, CSU Extension, Sterling CO

Terri Schultz, The Nature Conservancy, Ft. Collins, CO

Chris Tecklenburg, Ecological Site Specialist, Hutchison, KS

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Harvey Sprock, Daniel Nosal |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | Harvey Sprock, Area Rangeland Management Specialist, Greeley, CO |

| Date | 01/12/2005 |

| Approved by | Kirt Walstad |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Typically none. If present, water flow patterns are on steeper slopes following intense storms, short, and not connected. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

None -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

3 percent or less bare ground, with bare patches generally less than 2-3 inches in diameter. Extended drought can cause bare ground to increase upwards to 10-20 percent with bare patches reaching upwards to 6-12 inches in diameter. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

None -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Litter should be uniformly distributed with little movement. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Stability class rating is anticipated to be 5-6 in interspace at soil surface. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

Average SOM is 1-2 percent. A-horizon ranges from 0-9 inches. Soils are typically deep, light brownish gray, medium sub-angular blocky structure. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

Raindrop impact is reduced by the diverse grass, forb, shrub functional/structural groups and root structure. This slows overland flow and provides increased time for infiltration to occur. Extended drought, wildfire or both may reduce basal density, canopy cover, and litter amounts (primarily from tall, warm-season bunch and rhizomatous grasses), resulting in decreased infiltration and increased runoff on steep slopes following intense rainfall events -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Cool-season mid rhizomatous >Sub-dominant:

Warm-season short bunchgrass > cool-season mid bunchgrass and grasslikes > shrubs > leguminous forbs >Other:

Warm-season mid bunchgrass > warm-season forbs > cool-season forbs > warm-season short stoleniferousAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Typically minimal. Expect slight short and mid bunchgrass mortality and decadence during and following drought. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Litter cover during and following extended drought ranges from 15-25 percent. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

500 lbs./ac. low precip years; 1200 lbs./ac. average precip years; 1700 lbs./ac. above average precip years. After extended drought or the first growing season following wildfire, production may be significantly reduced by 300 – 500 lbs./ac. or more. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Invasive plants should not occur in reference plant community. Cheatgrass, Russian thistle, burningush, other non-native annuals may invade following extended drought or fire assuming a seed source is available. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

The only limitations are weather-related, wildfire, natural disease, and insects that may temporarily reduce reproductive capability.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.

| T1A | - | Excessive grazing. Lack of fire. |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Tillage. |

| T2A | - | Excessive grazing. Lack of fire. |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

| 1.1A | - | Excessive grazing. Lack of fire. |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1B | - | Non-use. Lack of fire. |

| 1.2A | - | Prescribed grazing. Prescribed fire. |

| 1.3A | - | Prescribed grazing. Prescribed fire. |