Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R116AY100MO

Karst Fen

Last updated: 5/28/2025

Accessed: 12/22/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 116A–Ozark Highland

The Ozark Highland MLRA, also known as the Salem Plateau, is an unglaciated dissected plateau composed of various sedimentary strata from the Paleozoic Era (Figure G1). This ecoregion, effectively covering the Precambrian igneous basement rock beneath, was impacted by the uplift of ancient igneous knobs, which represent the epicenter of the Ozarks near the east-central portion of the MLRA (i.e., MLRA 116C – St. Francois Knobs and Basins). Elevation ranges from about 300 feet on the southeast edge of the Ozark escarpment near the Mississippi River to about 1,600 feet in the west adjacent to the Burlington Escarpment of the adjoining MLRA, the Springfield Plateau (116B). The underlying bedrock includes mainly horizontally bedded Ordovician-aged dolomites and sandstones that dip gently away from the uplift’s apex in southeast Missouri. Older, Cambrian-aged dolomites are exposed on deeply dissected hillslopes, particularly in the Current River Breaks Landtype Association (LTA) of the Current River Hills Subsection (Nigh and Schroeder 2002). In some places younger, Pennsylvanian- and Mississippian-aged sediments overlie the plateau, such as in the White River Hills Subsection near the southwest corner of the MLRA. Relief varies, from the gently rolling Central Plateau Subsection, an ecoregion representing the headwaters of the major Ozark river systems, to deeply dissected River Hills Subsections of those same river systems lower in their respective watersheds (e.g., the Current, White, Gasconade, and Meramec).

Due to the age, degree of weathering, and carbonate (i.e., limestone and dolomite) nature of the bedrock, the Ozark Highland is a prominent karst region. The upland landscapes provide vast areas for groundwater recharge; as a result the MLRA is home to some of the largest springs in North America, including Big Spring in Carter County, MO; Greer Spring in Oregon County, MO; and Mammoth Spring in Fulton County, AR. The interaction of underlying karst geology and complex subsurface hydrology form Karst Fens.

Classification relationships

Ozark Highlands Section (222A)

Current River Hills (222Af), Black River Ozark Border (222Al), Meramec River Hills (222Ae), and Osage River Hills (222Ac), St. Francois Knobs and Basins (222Aa), Gasconade River Hills (222Ad), Central Plateau (222Ab), and White River Hills (222Aj) Subsections*

*in order of prominence based on known Karst Fen locations

Terrestrial Natural Community Type in Missouri (Nelson, 2010): The reference state for this ecological site is most like an Ozark Fen.

Ecological site concept

Karst Fen ecological sites are scattered throughout many river hills landscapes of the Ozark highlands (Figure G1). Although relatively uncommon and small in land area they are comparatively frequent in number. They are most common in the uppermost, gaining sections of the Current, Black, Meramec, Osage, and Gasconade River watersheds along 1st and 2nd order streams (Strahler, 1957). They are unique compared to fens from other Midwestern states, which occur in prairie landscapes where subsurface water percolates through calcareous glacial parent materials until it becomes perched above an impenetrable layer, discharging on a variety of slope types. Karst Fens occur in unglaciated forest-woodland landscapes and are defined by complex relationships among hydrology, geology, landforms, biota, and natural history. The predominant ecological process driving Karst Fen dynamics is the constant discharge of mineral-enriched groundwater producing a calcareous or near-calcareous wetland environment. These conditions produce unique soils that are rich in nutrients. Dark-colored, carbon-rich surface horizons with gray-colored subsurface horizons typify most sites. While they can occur as larger units (greater than four acres in size), they typically represent minor components of narrow valleys above major floodplains. Below Karst Fens, it is common to transition to a typical Ozark floodplain/stream sequence, where the hydrology of the fen is seemingly separate from the riparian environment.

The plant communities of Karst Fens are exceptionally biodiverse and are classified by the State of Missouri as imperiled (MDC, 2021). High-functioning Karst Fen ecological sites are dominated by highly conservative sedges, grasses, and forbs and are typically void of significant tree and shrub cover. Species unique to calcium-rich environments, such as orange coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida var. umbrosa) and those disjunct from their typical range, such as bristlystalked sedge (Carex leptalea), help define these plant communities. The latter are thought to be relicts of previous climatic periods that have remained in the stable, Karst Fen ecosystem. These species are emblematic of site stability and complexity. Among sites, variations in water table expression and landform produce variable plant community dynamics. In drier, seasonally saturated areas, species like little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) may be present and resemble a mesic tallgrass prairie. In moderately wet sites, species like fourflower yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia quadriflora) and inland sedge (Carex interior) are often common. In the wettest areas, which is the central concept and most common condition of Karst Fens, species like stiff cowbane (Oxypolis rigidior) and bottlebrush sedge (Carex hystericina) occur (Figure G2). Many Karst Fens are highly degraded, and as unique/disjunct species disappear from degraded locations their flora reflects more general Midwestern wetland community assemblages. Species like Dudley’s rush (Juncus dudleyi) and golden ragwort (Packera aurea) are common and occur in a variety of wetland types in the region but are highly correlated to both intact as well as degraded Karst Fens.

Karst Fens, although infrequent and often small in size are centers of biodiversity and have specialized ecosystem connections. The reliance of species like the Hine’s emerald dragonfly (Somatochlora hineana) epitomize this. Relationships with animal species such as the North American beaver (Castor canadensis) provide additional ecological complexity by adding areas of carbon-rich (vs mineral-rich), stagnant-water marshes with different nutrient cycling dynamics. Beaver-modified fens thus provide a unique dynamic creating an additional suite of ecological conditions for flora and fauna.

Associated sites

| F116AY035MO |

Wet Terrace Forest Wet Terrace Forests have wide distribution. Soils are very deep with loamy to clayey subsoils, have a high water table in the Spring months, and are subject to flooding. The reference plant community is forest of bur oak, Shumard oak, swamp white oak, American elm, and black cherry, an understory dominated by American hornbeam, northern spicebush, and Ohio buckeye and a rich herbaceous ground flora. |

|---|---|

| F116AY032MO |

Loamy Footslope Forest Loamy Footslope Forests have wide distribution. Soils are very deep, typically with loamy surfaces and loamy or clayey subsoils. The reference plant community is forest of white oak, sugar maple, northern red oak, bitternut hickory, American elm, walnut and Kentucky coffeetree, an understory dominated by pawpaw, northern spicebush, eastern leatherwood, and Ohio buckeye and a rich herbaceous ground flora. |

| F116AY037MO |

Gravelly/Loamy Upland Drainageway Forest Gravelly/Loamy Upland Drainageway Forests are widely distributed and found in narrow upland drainageways. Soils range from loamy to very gravelly, and are subject to flooding. The reference plant community is forest of white oak, black oak, northern red oak, elm and hickory, an understory dominated by flowering dogwood and American hornbeam and an herbaceous ground flora dominated by wildrye and sedge. |

| F116AY034MO |

Loamy Terrace Forest Loamy Terrace Forests have wide distribution. Soils are very deep and loamy, and are subject to flooding. The reference plant community is forest of sugar maple, northern red oak, bitternut hickory, bur oak, American elm, black walnut and Kentucky coffeetree, an understory dominated by pawpaw, northern spicebush, Ohio buckeye and eastern leatherwood and a rich herbaceous ground flora. |

Similar sites

| R116AY026MO |

Wet Upland Drainageway Prairie this is similar to the karst fen in having additional water, but lacks the organic material in the soils. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Alnus serrulata |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Carex leptalea |

Physiographic features

Due to a variety of ecological factors, Karst Fen sites are a unique component of select river hills ecoregions in the southeastern portion of the Ozarks. The majority (78 percent) of fens documented by the Missouri Natural Heritage Program occur within just four of 16 Ecological Subsections, including the Current River Hills, Meramec River Hills, Black River Ozark Border, and Osage River Hills (Nigh and Schroeder 2002). Within these ecoregions, Karst Fens are largely located in the upper portions of dissected river hills landscapes (i.e., LTAs) coincident with the first sign of discharging spring/seepage flow into the valley system. Overall, it is difficult to separate the physiographic features essential to Karst Fen formation without considering the associated relationship of geology, geomorphology, and hydrology.

Importance of Geology:

In other parts of the country, underlying geology has been found to be a better predictor for groundwater-based fen locations than landforms because of the geologic controls of shallow groundwater storage, lateral flow, and subsequent diffuse discharge of groundwater (Aldous et al. 2015, Francle et al. 204). This is certainly the case with Karst Fens in the Ozarks as well. Understanding site geology, therefore, is vital to determine flow paths of groundwater and subsequent discharge into fens. Fens can be found across a variety of landscape positions because consistent groundwater discharge may be produced from multiple subsurface sources (Grootjans et al. 2006). The permeability of the soil, bedrock type, water pathways, rate of movement, and linkages to local or regional aquifers are all important factors when understanding how geology and subsurface hydrology contribute to the function of these wetlands (Froend et al. 2016). Areas of limestone or dolomite bedrock near the ground surface, which have the potential to create karst features, make up 18 percent of the United States land base (Tiner 2003, Weary and Doctor 2014). These conditions contribute to specific kinds geographically isolated wetland types, such as sinkholes and fens. While much of this karst terrain lies in two swaths across the east coast and the Appalachians, another pocket is centered over the Ozark Highlands of southern Missouri and northern Arkansas (Figure P1; Land and D'Amico 2016). Overall, understanding the importance of multiple subsurface interactions is critical for defining wetlands in karst systems, providing additional context to the understanding of existing landform features (Beltram 2016).

Karst Defined:

Karst is a type of landscape formed by the dissolution of soluble limestone or dolomite bedrock, producing collapsed surficial landforms and subsurface bedrock voids. Limestone and dolomite are often called carbonate rocks because of their mineral composition, which is dominated by carbonate ions (CO3). Because of their mineral makeup, these carbonate rocks become soluble when exposed to acidic water and CO2 (Beltram 2016). In the case of the Ozarks, much of the region is covered by a thick layer of carbonate bedrock, mostly dolomite (Figure P1). Over the course of millions of years the infiltration of naturally acidic rainfall dissolved the dolomite rock along fractures and faults. With time these pathways became enlarged, allowing more water to percolate at greater quantities and depths. This enlargement further accelerates the dissolution of rock, forming larger conduits and cavities, resulting in active cave systems. This process is called karstification (Hartmann et al. 2014, LeGrand 1983). There are differences within the various Ozark MLRAs in geology and degree of karstification that occurs among the various bedrock ages and formations. Older geologic formations, for example, have allowed more time for weathering and cave systems to develop (Adamski 1995, Nelson 2005).

Lithology and Geologic Formation:

Although karst topography is more easily observed at the surface, the age and composition of the underlying bedrock is critical to understand. The geologic base of the Ozarks is an uneven plane of hard igneous rocks composed of rhyolite and granite that formed 1.5 to 1.2 billion years before present (BP) during the Precambrian Period (George 2007, Hayes et al 2016, Orndorff et al. 2001). The overlying sedimentary formations are much younger and are largely dolomites, with intermittent layers of cherts and sandstones that were formed 542 to 444 million years BP during the Ordovician and Cambrian Periods (Hayes et al 2016, Orndorff et al. 2001). In the Ozark Highland MLRA, the major geologic formations include, from young to old: Jefferson City-Cotter Dolomite, Roubidoux Formation, Gasconade Dolomite, and Eminence-Potosi Dolomite (Figure P2; Adamski et al. 1995, Weary et al. 2004, Weary and Orndorff 2016).

Orzell’s (1983) seminal work on fen and seepage ecosystems in the Ozarks remains the most thorough and ecologically integrated work on this topic to date. Most of the fens he studied were associated with the Eminence-Potosi Dolomite Formation. As a result, it was originally thought that fens in the Ozarks were mostly limited to these formations. However, the Orzell study was confined to a four-county area where the Eminence-Potosi Dolomite Formation is particularly prominent. A later study by George (2016) attempted to better define hydrogeomorphic relationships of fens and found considerable fen occurrences across a broader range of geologic formations, particularly the Gasconade Dolomite. Overall, 70 percent of the fens he examined occurred within either the Gasconade or Eminence-Potosi Formations. Similarly, data from the project supporting this publication, working to expand on George’s work, validated his findings and found 82 percent of fens associated with those same formations (MTNF 2021). Finally, a remote analysis of the all 356 mapped fens by MTNF, Missouri and Arkansas Natural Heritage Databases (2021), George (2016), Orzell (1983), further verify a large majority of Karst Fens occur in Gasconade Dolomite and Eminence-Potosi Dolomite Formations (Figure P3). Although a minor component, Karst Fens also occur in the Jefferson City-Cotter and Roubdioux Formations. It is important to note that although the Roubidoux Formation includes comparatively few fens, when exposed at the surface this formation produces significant karst topography and represents an important recharge impact to fens that occur in the Gasconade and Eminence-Potosi Formations lower in the watersheds.

Horizontal Orientation and Fracturing:

Although mostly sedimentary in origin, the geology of the Ozarks was impacted by numerous volcanic uplifts. This created an elliptical dome with igneous rock protruding from the center and forms the St. Francois Knobs and Basins MLRA (Figure G1; Adamski et al. 1995, Hayes et al. 2016). Although the overlying sedimentary rock was deposited in a horizontal manner, uplift of the igneous “basement rock” caused a gradual slope of the bedrock plane away from the St. Francois Mountains, which impacted the other adjacent Ozark MLRAs (Figure P4; Adamski et al. 1995).

The combination of unlevel basement geology and multiple periods of uplift contributed to the sedimentary bedrock layers becoming fractured, jointed, and faulted. In terms of geographic distribution, the closer you are to the St. Francois Knobs area, the more faults there are (Figure P4; George 2007). Less weathered dolomite layers generally have low permeability. However, fracturing within and across various formations and layers of interbedded sandstones and cherts allow water to more effectively infiltrate and move through the rock (Figure P5a and b; Imes and Emmett 1994, Orndorff et al. 2001). Perched groundwater collects in these layers and moves laterally along the more restrictive dolomite bedding planes (Orndorff et al. 2001, Weary and Orndorff 2016). It is along these vertical and horizontal conduits that over millennia water has dissolved the bedrock and created karst cavities, eventually allowing groundwater to reach the ground surface and form Karst Fens.

Landform:

Because of the unpredictability of locations of groundwater discharge, Karst Fens can occur on multiple landforms (Table P1). In comparison to upland ecological sites, wetlands should be more strictly viewed from an integrated, hydrogeomorphic perspective (citation??). The geomorphic part of this (i.e., landforms) can help explain types and functions of wetlands when considered in combination with hydrology. Fens are often classified as “slope” wetlands because they develop at points of groundwater discharge (Brinson 1993). This often occurs along hillslopes, where a sudden change in elevation and topography intercepts and discharges groundwater moving laterally above an impermeable layer (Figure P5f, Amon et al. 2002, Brinson 1993, Dixon 2014). In Karst Fens, we interpret that the restrictive layer is usually a consolidated dolomite bed, but layers of sandstone, shale, or impermeable clay are also possible. How the underlying geology influences lateral flow in part defines why fens may occur on a variety of landforms and slope positions. Further, the angle of slope can also be variable and may range from zero to 30 percent, but most are on lower slopes between two and ten percent (Dixon 2014). Overall, Karst Fens are most commonly located on colluvial base slopes (i.e., footslopes and toeslopes) or the upper portion of stream terraces in upland drainageway settings. To a lesser extent, they also occur on backslopes, floodplains, meander scars on terraces, and alluvial fans (Heidel et al 2017, George 2016, Orzell 1983). However, no matter the landform, a key distinction of fens is hydrologic in nature and the development of soils high in organic matter that develop over time because of the persistent groundwater discharge at a rate that is low enough to prevent erosion but consistent enough to minimize cycling and decomposition (Amon et al. 2002).

Size:

The size of fens across the United States can be quite variable (Dixon 2014, Heidel et al. 2017). In the Midwest, fens were often too small to be mapped by typical 1:24,000 scale soil surveys. If mapped at all, many fen sites were identified via wetland “spot symbols”. These small wet spots, often a few acres or less, were either considered inclusions or unmapped minor components within the broader soil map unit (Dixon 2014, Lynch and Weckwerth 2017). The fens that were large enough to be mapped out were often not because of low overall acreage of the potential map unit. For these reasons, fens and other small wetlands were overlooked, resulting in uncertainty about their true historical extent (Dixon 2014). In the case of Karst Fens, ditching, wetland drainage, and agricultural conversion further add to the confusion about original extent. Today, something considered a large fen might only be an acre or two. Occasionally, a valley bottom may be marked by multiple fens in close proximity to form a fen-bottomland complex of 25 acres or more. However, this is more often the exception than the rule. The best example of a remnant Karst Fen complex is Grasshopper Hollow in Reynolds County, Missouri, which is over 40 acres in size. Undoubtedly, there were many more similar large fen complexes prior to European settlement. Today, many of the highest quality fen sites remaining are considerably smaller and may only cover 15 feet in diameter and swallowed by the larger forest matrix (Nelson 2005). In these instances, the saturated fen footprint isn't big enough to create herbaceous openings within the forest canopy. Despite their diminutive size the diversity of conservative plant species can be remarkably high (Lynch and Weckwerth 2017).

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Karst

> Fen

|

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Very low to low |

| Flooding duration | Very brief (4 to 48 hours) |

| Flooding frequency | None to rare |

| Ponding frequency | None to rare |

| Elevation | 400 – 1,400 ft |

| Slope | 2 – 30% |

| Ponding depth |

Not specified |

| Water table depth | 3 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

Historic Climate:

Historic climate changes during the late portion of the Pleistocene Epoch strongly influenced biotic changes in the Ozarks over the last 40,000 years. The effects of last glacial maximum are evident not only from fossil assemblages but from the present Ozark biota. Boreal plants and animals from the north migrated into the Ozarks ahead of the advancing ice along with the onset of glacial climatic conditions. The Missouri Ozarks were covered by open pine-parkland from at least 40,000 years BP until the peak of the last ice age (~20,000-25,000 years BP), and transitioned to boreal spruce forest until at least 13,500 years BP (Everett 1984). Deciduous elements became more prominent in the spruce forest towards the end of the Pleistocene, which ended some 12,000 years BP. Climatic changes occurring during the following Epoch (the Holocene) continued to influence plant and animal communities in the Midwest. With deglaciation, some species remained in uniquely suitable habitats. Many of the present endemic fen species and disjunct populations were products of these Pleistocene environmental changes (King, 1973). During the mid-Holocene (~6,000 years BP) the Midwest was warmer and drier than at present, and existing organic soils in wetlands were degraded completely or accumulated slowly in across the region. Several studies put the period of maximum dryness in the Midwest sometime between 6,300 and 5,000 years BP (Baker et al. 1990; Van Zant 1979; Van Zant and Hallberg 1976). During this time, oak-grass parkland defined the upland vegetation of the Ozarks (Everett 1984). Water levels of lakes and marshes were significantly lower than at present (Van Zant 1979; Baker et al. 1990) and, by inference, shallow groundwater levels were also lower. Investigations at lakes in other parts of the Midwest have shown that several periods of extended or recurrent drought occurred during the middle Holocene (Bryson et al. 1970; Dean et al. 1984; Forester et al. 1987). These drought conditions accompanied by depressed groundwater levels would not have been favorable for organic soil accumulation; therefore it seems likely that fen formation ceased or was very reduced during the mid-Holocene (Thompson and Bettis 1994). Following the dry period in the Ozarks, a transition from oak-grass parkland to modern shortleaf pine-oak woodland occurred by 3,500 years BP (Everett 1984). Current field investigations, including that of this project, indicate that numerous plant species representative of the previous glacial climatic environment remain in Karst Fens as disjunct southern populations.

Current Climate:

Today, the Ozark Highland MLRA has a continental type of climate marked by strong seasonality (Figure C1). In winter, dry-cold air masses, unchallenged by topographic barriers, periodically move south from the northern plains and Canada (USDA 2006). If these masses interact with reasonably humid air, precipitation as snow and rain result. In summer, moist, warm air masses, equally unchallenged by topographic barriers, move north from the Gulf of Mexico and can produce abundant amounts of rain, either by fronts or by convectional processes. In some summers, high pressure stagnates over the region, creating extended droughty periods, which in part helps define the location of oak-hickory ecosystem of the Midwest. Spring and fall are transitional seasons when abrupt changes in temperature and precipitation may occur due to successive, fast-moving fronts separating contrasting air masses. The Ozark Highland experiences regional differences in climates, but these differences do not have obvious geographic boundaries. The basic gradient for most climatic characteristics is along a line crossing the Ozarks from northwest (cooler and drier) to southeast (warmer and wetter; USDA 2006).

Mean annual precipitation for the Ozark Highland is 38 to 45 inches (Figure C2, Tables C1 and C2). Snow falls nearly every winter, but the snow cover typically lasts for only a few days or less. Mean annual precipitation varies along a northwest to southeast gradient. Seasonal climatic variations are more complex. Seasonality in precipitation is very pronounced due to strong continental influences. June precipitation, for example, averages three to four times greater than January precipitation. Most of the rainfall occurs as high-intensity, convective thunderstorms in summer (USDA 2006).

Mean annual temperature is about 53 to 60 degrees F (Figure C3). The lower temperatures occur at the higher elevations in the western part of the MLRA. Mean January minimum temperature follows a strong north-to-south gradient. However, mean July maximum temperature shows little geographic variation in the MLRA, having a range of only two or three degrees across the area.

During normal precipitation years, moisture is stored in the top layers of the soil during the winter and early spring, when evaporation and transpiration are low (Figure C1). During the hot summer months the loss of water by evaporation and transpiration is high, and if rainfall fails to occur at infrequent intervals, drought will result. Drought directly affects plant and animal life by limiting water supplies, especially at times of high temperatures and evaporation rates (Decker 2016). Field observations in the Ozarks, however, show Karst Fen ecological sites, due to groundwater connectivity, tend to remain permanently wet and only in extreme drought conditions dry up significantly. These drier periods within the Karst Fen environment occur near the end of the growing season, and quickly recharge in the fall and winter.

Microclimate:

Superimposed upon Ozark Highland climatic patterns are microclimatic variations. In areas of higher relief, for example, air drainage at nighttime may produce temperatures several degrees lower in valley bottoms than on uplands. At critical times during the year, this phenomenon may produce later spring or earlier fall freezes in valley bottoms. Deep sinkholes often have a microclimate significantly cooler, moister, and shadier than surrounding surfaces, a phenomenon that result in a strikingly different ecology. Higher daytime temperatures in areas of rock outcrop and higher reflectivity of these unvegetated surfaces create distinctive environmental niches in glade and cliff ecological sites. Slope orientation is also an important topographic influence on climate, and often supersedes many other ecological site factors, including soils. High summits and south-and-west-facing slopes are regularly warmer and drier than adjacent north- and-east-facing slopes occurring at the same elevation. Finally, the microclimate within a canopied forest is measurably different from the climate of a more open grassland or savanna areas (Decker 2016).

Fen microclimatic effects

Fens have a local microclimate distinct from surrounding ecological sites. As described previously, many Karst Fen plants are glacial climatic relicts that were retained on the landscape only in moist, cool sites like fens and shaded cliffs and coves. These species would have been common across the Ozark landscape 10,000 years BP but were largely extirpated as the Ozark climate warmed. Since Karst Fens are usually saturated at or near the ground surface due to permanent or near-permanent groundwater discharge, hydrology in this way significantly shapes microclimates at the soil-atmospheric interface (Glaser et al. 1997). Prior to discharging to the terrestrial surface in fens, groundwater comes into equilibrium with subsurface temperatures where conditions reflect long-term yearly average air temperatures (Raney et al. 2014; Bedford and Godwin 2003; Wisser et al. 2011). Groundwater discharge to fens is relatively cool in the summer months and warm in the winter months (Frederick 1974); thus, soil temperatures do not get as warm or as cold as the soils in surrounding ecological sites. As a result, fen soils rarely freeze, even during exceptionally cold winter weather. In addition, the constant groundwater near the surface dampens extremes in humidity and air temperature, both on a daily and seasonal basis. Relative humidity near the soil surface is more consistently damp, compared to greater swings in humidity in adjacent ecological sites.

An example of an ecosystem-microclimatic connection in Karst Fens is the presence of some tussock-forming sedges (Figure C4). Examples such as inland sedge and dioecious sedge (Carex interior and C. sterilis, respectively) which are obligate to Karst Fens, produce mound-like tussocks that rise slightly above the usually oxygen-poor soil surface and thus create their own microsites that have a moisture and temperature gradient. The tussocks are saturated near the peat interface and drier toward the top. In addition, solar radiation makes the south-and-west-facing sides of these tussocks warmer and north-and-east-facing sides cooler. These various zones provide unique moisture and aspect niches and result in high plant and insect diversity (MIDNR 2010).

Climate Change Observations and Predictions for the Ozark Highland:

General circulation models for the central United States predict increasing temperatures through 2050, including an annual mean temperature increase ranging from three to six degrees F across the Ozark Highland MLRA (CITATION NEEDED). Hydrologic model projections indicate that soil moisture, runoff, and streamflow may increase during the spring as precipitation increases. Model projections suggest that snow cover and duration will continue to decrease over the next century. Extreme precipitation events are projected to increase, particularly the frequency of spring-time downpours (Hayhoe et al., 2017; Wuebbles et al., 2004; Brandt et al., 2014). Specifically, the Midwest (including Missouri) is predicted to have wetter conditions in April and May and drier conditions in July and August (Patricola and Cook, 2013). Heat waves are predicted to become more frequent and occur over longer durations (Patricola and Cook, 2013). Despite variability in individual outputs, climate models collectively predict increased periods of water stress due to some combination of changing seasonal inputs of precipitation and periods of drought. Demands on groundwater resources in the Ozark system are likely to increase in the future (Hays et al., 2016). Ultimately, this suggests that some that some rare ecological communities (like Karst Fens) will face stress and may struggle to maintain historical ecological dynamics (Brandt et al., 2014).

A report by Pavlowsky et al. (2016) was completed within the core of Karst Fen distribution and analyzed historical rainfall patterns for the Big Barren Creek watershed, a major tributary to the Current River. Data were analyzed from the period of 1955 to 2015 and concluded the following climatic trends:

• Annual rainfall totals show an overall increase during the study period, with a historically wet period from 2005 to 2015.

• Analysis of the rainfall record in five-year intervals show that high magnitude events are occurring more frequently over the previous decade. During this time, the one percent exceedance rainfall events have increased 21 percent compared to the prior 20 years.

• Seasonal analysis of the entire 60-year record by season shows the highest rainfall totals tended to occur in the fall and spring; but the frequency of these same event over the past decade are increasing in winter, spring, and summer.

• The recent increase in extreme precipitation events is causing more out-of-bank floods, geomorphic changes, and excess gravel deposition in stream channels. It is highly probable that more intense storms and changing climatic patterns in general are contributing to the hydrologic problems observed in the Big Barren Creek watershed, including the increased frequency of flooding.

If increased precipitation patterns identified by Pavlowsky et al. (2016) continue, such extreme events don’t preclude the potential for ecosystem-altering drought patterns. Soil and groundwater recharge may be negligible due to increased runoff as overland flow. If increased rainfall occurs during non-growing season times, impact to vegetation may be limited.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 156-161 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 178-188 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 45-48 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 155-162 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 177-193 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 45-49 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 158 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 183 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 47 in |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 3. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) EMINENCE 1 N [USC00232619], Eminence, MO

-

(2) ALTON 6 SE [USC00230127], Alton, MO

-

(3) DONIPHAN [USC00232289], Doniphan, MO

-

(4) ROUND SPRING 2SW [USC00237309], Eminence, MO

-

(5) CLEARWATER DAM [USC00231674], Ellington, MO

Influencing water features

Hydrology is the most influential ecological site factor driving Karst Fen development, persistence, and maintenance. These fens rely on year-round flow of calcium-enriched groundwater from adjacent karst recharge areas and depending on landform, can receive additional hydrologic sources from flooding or beaver impoundment. Although hydrology is important for all wetland types, the influencing water features for Karst Fens are particularly complex.

Watershed Context and Hydrologic Recharge:

Most fens are located in upper watershed positions associated with small order streams. When combining sites tracked by the Missouri Natural Heritage Program and those studied by Orzell (1983), we found 75 percent occur along either 1st or 2nd order streams as defined by Strahler (1957). When adding in 3rd order streams this number increases to 89 percent, with 11 percent of fens located along 4th through 6th order streams. Typically, within these upper watershed reaches the only option for groundwater recharge is localized infiltration. Thus, although a large proportion of fens occur along first order streams, the conditions for fen formation in these settings don’t begin until the recharge area is large enough to discharge groundwater via diffuse flow, seeps, and small springs. By comparison, larger order streams can receive similar localized discharge but are more likely to be associated with subregional to regional flow, resulting in large discrete spring systems (Figure P5, Duley and Boswell 2017, Bertrand et al. 2012, Dahl et al. 2007).

Groundwater recharge refers to the surrounding source area(s) of water that infiltrate into the ground. Precipitation as rainfall is the main source of recharge within the Ozark Highland. Although much of this water comes from sinkholes, collapse features, karst valleys, and losing streams – there are substantial contributions from the broader upland landscape. Specifically, areas where the surrounding landscape includes highly weathered geologic materials with deep, porous, and unconsolidated rock capable of storing and moving groundwater. An excellent example of this includes the Current River Pine-Oak Woodland Dissected Plain LTA. This landscape is mantled by interbedded sandstone, chert, and weathered dolomite and represents some of the most significant karst topography in the Ozarks. While this LTA is characterized by dry acidic pine-oak woodlands, it represents a vast area of hydrologic recharge for the fens, seeps, springs, and streams of the Current and Eleven Point Rivers. Areas of highly weathered materials in the Gasconade and Eminence Dolomite Formations produce similar recharge potential. Once leaving the surface, much of the rainfall is stored as groundwater infiltrating through discrete, subsurface pathways in the form of fractures, faults, and cave conduits.

In karst landscapes, the upper headwaters consist of losing streams, typically devoid of fens. Orzell (1983) noted the lack of fens within valleys of losing stream reaches, which like fens, are usually associated with 1st or 2nd order streams. Along small order streams, gaining sections appear, defining the point where fen formation is possible. To better understand the connection between these areas of groundwater discharge and recharge areas, multiple dye-trace studies have examined fens in the Ozarks (Aley and Adel 1991, Aley and Aley 2004, Aley and Moss 2006, Beeman and Aley 2012, Beeman and Aley 2013, Beeman and Aley 2015). These studies show rainfall infiltrating or recharging localized shallow aquifers within the immediate adjacent uplands, moving downhill laterally through the fractured bedrock, and discharging at low or diffuse rates within the fens (Figure W1). In one case, a dye tracing study at Grasshopper Hollow in Reynolds County, Missouri documented inter-watershed movement, highlighting the hydrologic complexity of fens in a karst environment (Aley and Adel 1991). These studies show a rather large range in calculated recharge area, from less than 100 to over 2,000 acres, with most being in the 150-300 acre range. Presumably, small, isolated fens have smaller recharge areas, while large fens and complexes of numerous fens within a valley system have larger recharge areas. Small fens with recharge areas of 100 acres or less are unique compared to fens in the upper Midwest. For example, in Iowa, Thompson and Bettis (1994) estimated most fens in that region had recharge areas of less than 6,200 acres, which they considered to be small. Despite recharge areas for many Karst Fens being relatively small, the rate of diffuse discharge is low enough that storage in these locally perched aquifers is not easily depleted and periodic groundwater recharge from seasonal rainfall events is sufficient to sustain persistent flow.

Karst Connections:

Understanding the implications of how the past has shaped the landscape and influenced the geology and hydrology is imperative in karst systems. Water has weathered the surface bedrock in the Ozarks for hundreds of millions of years. The region, once an ancient plateau, is now covered by a variably thick mantle (0 to hundreds of feet) of weathered, unconsolidated materials made up of clay, silt, sand, gravel, cobble, and boulders over bedrock that now form a dissected plateau (Figure W2; George 2007, Weary et al. 2004, Hays et al. 2016). Water infiltration can vary based on soil texture and rock content, but overall, permeability of these unconsolidated materials is high, allowing water to easily move through the soil and into the partially weathered portion of the bedrock (Beveridge and Vineyard 1990).

Water has also weathered bedrock internally along interstitial spaces, fractures, and crevasses. (Figure W3). The uppermost zone includes the soil and partially weathered surficial layers of bedrock is referred to as the epikarst, which can vary in thickness and depth from a few inches to 100 feet or more (Berthelin and Hartmann 2020, Trcek 2007). Here the naturally acidic infiltrating rainwater dissolves the dolomite rock and becomes saturated with calcium. Hence, the epikarst is commonly the most fractured and permeable layer (Berthelin and Hartmann 2020, George 2007, Goldschieder 2012, Grimes 1999, Trček 2007, Figure P5).

Epikarst lies above endokarst and in these systems endokarst is less porous, causing water to perch above it. This stored water moves horizontally until it reaches major faults and/or larger conduits moving into the karst matrix (Aley and Kirkland 2012, Grimes 2009, Trček 2007). Aside from temporarily perched groundwater, the epikarst and upper portion of the endokarst are largely unsaturated. Some horizontal flow does occur within the endokarst in deeper locations where the water table interacts either temporarily or permanently with horizontal fractures and/or bedding planes in the intermediate and saturated zones of the endokarst (Audra and Palmer 2015, Grimes 1999, Figure W3). In the Ozarks, these locations of karstification and subsequent cave formation often occur at the intersection of sandstone layers and dolomite bedding planes (Orndorff et al. 2001, Weary and Orndorff 2016, Figure 5b).

The variation of permeability caused by internal weathering within the karst matrix causes water infiltration to be slow in some locations (i.e., diffuse flow) and concentrated and fast in others (i.e., conduit flow). This creates complex and interconnected subsurface pathways controlled both by geologic boundaries and faulting impacts (Aley and Kirkland 2012, Audra and Palmer 2015, Berthelin and Hartman 2020, Goldschieder 2012, LeGrand 1983).

Landform Influence:

In addition to geology and hydrology, geomorphology helps define Karst Fens. Groundwater will discharge following a path of least resistance: usually at the break of a slope (e.g., a footslope, toeslope, or valley bottom adjacent to the upland edge). At times, concave landform features may influence direction and pirating of flow. Examples include steep headslopes and watercourses on valley sides or in meander scars or sloughs on terraces or floodplains. In other cases, groundwater pathways may direct water to the middle of an upland backslope above a small order stream.

Landscape position and its connection to aquifers plays a factor in the stability of the water table and groundwater discharge. For example, fens within floodplains have been shown to benefit from the larger regional aquifers that are also contributing to the adjacent stream's base flow (Duval and Waddington 2018). This appears evident in the Ozarks based on field data supporting this publication, as fen soils sampled in valley bottoms are far more likely to show signs of regional water tables along with the typical perched through-flow from karst discharge. Fens on hillslope positions only receive water from upslope sources moving laterally through the epikarst. During periods of drought, fens in these locations and their respective plant communities are more vulnerable to water table fluctuations and desiccation.

Groundwater Discharge and Water Table:

Groundwater discharge is the emergence of water to the ground surface from a subsurface aquifer. The distinction of groundwater discharge as the primary water source in fens separates them from other wetland types. In contrast, wetland types like sinkhole ponds are primarily influenced by precipitation, whereas riverine wetlands are influenced by overland flow (Figure W4, Brinson 1993, Thobaben and Hamilton 2014).

Areas of groundwater discharge range considerably in volume and velocity of water both spatially and temporarily. Seeps are locations where flow is not detectable, whereas springs discharge at a high enough rate and volume that flow is detectable and powerful enough to move soil and organic matter and prevent the establishment of vegetation. Fens fit in the middle of this flow-based continuum (O'Driscoll et al. 2019) and are often marked by diffuse flow that is slow enough to maintain saturated soils, inhibit decomposition, and contribute to the build-up of organic soil (Aldous et al. 2015, Amon et al. 2002, Choesin 1997).

Limestone/Dolomite Springs are classified as a unique natural community type having distinct vegetative composition and structure (Nelson 2005). The Ozark Highland MLRA is known for the highest density of large discharge springs in Missouri (Hays et al. 2016, Vineyard and Federer 1982). Despite this, the specific geophysical characteristics of the region's springs are not well defined. However, spring ecosystem classification system has helped better define spring types (Bertrand et al. 2012, O'Driscoll et al. 2019, Scarsbrook et al. 2007, Springer and Stevens 2009, Stevens et al. 2020). This system provides universal terminology to describe the variability that can occur within and across sites both in Missouri and nationally.

Overall, springs can be grouped into two main categories: lentic or lotic (Stevens et al. 2016). Lentic springs are associated with standing water or habitats where water flow is minimal compared (Stevens et al. 2016). Lotic springs on the other hand are associated with visibly moving water. It is at these locations of groundwater discharge where a distinct edge or border exists between the upslope slope boundary and the fen (Figure W5; Amon et al. 2002, Dixon 2014).

Most Karst Fens are fed by lotic springs and can be further defined as lotic helocrene springs. Helocrene springs are marked by diffuse discharge of groundwater creating saturated soils and marshy conditions. The seepage of water from these springs is often associated with subsurface geology. This definition includes seeps, fracture springs, and fens (Scarsbrook et al. 2007, Stevens et al. 2020). Vineyard and Federer (1982) who wrote the Springs of Missouri discuss seepage or infiltration springs as areas of low groundwater discharge, which would likely be classified as helocrene springs in this broader framework. Fracture springs are another type of helocrene spring where groundwater flows along faults, fractures, and bedding planes (Vineyard and Federer 1982). Fracture springs are are often associated with higher discharge rates and in certain locations these springs can discharge water a low enough rates to prevent erosion and maintain saturated soils, qualifying them as helocrene springs. The low velocity of these diffuse springs contribute to the build up of organic matter and are the primary spring type contributing to fens in the Ozarks. Other spring types can also exist as part of these habitats depending upon site conditions and hydrology.

While much of the water moving through fens is through the soil substrate, fens can also contain narrow areas of concentrated flow, sometimes called rheocrene springs. These can be stable or in a state of degradation, pointing towards changes in the site's hydrology. There are a number of names for these minor flow channels in the literature including: springbrook, spring run, rivulet, streamlet, and runnel (Stevens et al. 2020, Hayes et al. 2016, Kay et al. 2018, Molnar 2016, Bedford 1999, Menichino et al. 2015). Karst Fens can often contain minor components of rheocrene springs in the form of rivulets. These minor flow channels are not vegetated and can provide important fire breaks and contribute to fen heterogeneity (Bowles et al. 2005).

Mound-form springs may also develop from a buildup of organic matter over time which accumulates and elevates the topography (Springer and Stevens 2009, Stevens et al. 2020). This kind of spring system is not well docmented in the Ozarks. Blair Creek Raised Fen in Shannon County, Missouri is the only known mound-form spring associated with Karst Fens. These fens may form from the lateral flow of groundwater through the epikarst as opposed to the upwelling of water that may occur at a tubular or fissure geologic feature.

Water table fluctuations in fens can vary among sites and region. Outside of Missouri fen water tables have been documented to seasonally fluctuate 8-30 inches depending upon the location and the size of aquifer (Lamers et al. 2018, Moorehead 2001, Wierda et al. 1997). Other fen types have been shown to be relatively stable, potentially buffered by larger regionally sustained aquifers (Duval and Waddinton 2012, Sampath et al. 2016, Schilling and Jacobson et al. 2015, Thompson et al. 2007). Although fen aquifers in the Ozarks aren’t considered large, water table variation is thought to be remarkably stable, usually at the surface for much of the year, and may draw down a matter of a few inches during the driest times of the mid- to late-summer. Snowmelt and spring rains can contribute to greater discharge earlier in the year, but since most fens have slope, the water table is maintained at the soil surface. In comparison, high evapotranspiration rates and summer drought reduce discharge, but not so much that the water table is significantly altered (Ahmad et al. 2020, Thobaben and Hamilton 2014).

The information shared here is focused on our central concept of Karst Fen. This is the most common fen condition, experiencing perennial discharge and constant saturation, which is indicative by the wetland flora present, mucky soils, and reduced iron within the soil profile. Other fens are more impacted by water table fluctuations and occasional dry conditions (i.e., prairie fens). These locations are poorly understood and are marked by mesic prairie species, scattered wetland plants, and show signs of transient water tables below the ground surface.

Water Temperature and Chemistry:

Groundwater temperatures are fairly constant and range between 55 and 62 F (Mason 2013). Once the water surfaces and percolates through a fen, water temperature influences soil temperature (Amon et al. 2002). This creates a microclimate buffered from the seasonal ambient temperature fluctuation, keeping the fen cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter, buffering against freezing or near freezing conditions (Denny 1994, Fernández-Pascual et al. 2015, Horsak et al. 2018).

Many plant species associated with Karst Fens are considered disjunct climate relicts found mostly in the Great Lakes states and Canada (George et al. 2016, Orzell and Kurz 1987, Vitt and Horton 1990). During the cooler climate of the last glacial cycle the entire Ozark Highland had ecosystems similar to boreal forests (King 1973). As the region's climate and vegetation shifted to a warmer and drier community, the constant discharge of cool groundwater in fens buffered changes in regional moisture and temperature extremes. These conditions allowed for the proliferation of fen vegetation to persist and populate Karst Fens (King 1973, Orzell 1983, Steyermark 1955, Vitt and Horton 1990).

Fens are through-flow systems and groundwater moving through these wetlands reflects both the chemistry of the soils and water-rock interactions within the recharge area. As water is exposed to air, organic soil, soil microbes, and plant roots other chemical reactions may occur, causing minerals and nutrients to interact and either be more available for plant uptake or rendered inaccessible depending on whether minerals and elements are deposited or removed. These geochemical interactions vary depending upon temperature and groundwater discharge rate, contributing to variation in water chemistry across space and time (Bowles et al. 2005, Motzkin 1994).

Soil and water chemistry in fens produce a suite of conditions that result in unique and diverse plant communities, and can be classified as poor (pH <5.5), rich (pH 6-6.5), or extremely rich (pH >7) (Amon et al. 2002, Francl et al. 2004, Heidel et al. 2017, Lamers et al. 2015, Vitt and Chee 1990, Zoltai and Vitt 1995). In the Ozarks, relatively short residence times within the headwater epikarst produce neutral to alkaline pH conditions and variable to high conductivity (George 2016). This indicates that Karst Fens are in the middle of the two extremes between poor and extremely rich fens found elsewhere in the world (George 2016).

The influence of pH and conductivity varies across a given fen. Alkalinity is often highest at the source of groundwater discharge and decreases further away, resulting in cascading plant composition (Choesin 1997). Although not common in the Ozarks, extremely rich fens can have calcium concentration so high that it can be toxic to plants, limiting the plant community to a small group of species (Sjörs 1959). Similarly, the conditions required to produce calcite precipitation to develop marl or tufa are seldom manifested Ozarks (Schaper and Wicks 2002). Soil investigations supporting this publication at well-known “marl fens” in Missouri appear to be the result of anthropogenic in origin, possibly resulting from peat mining or some other severe historic disturbance.

Other Hydrology Sources:

Depending on landform, some fens can receive additional sources of hydrology. Natural impoundment of spring water on terraces or floodplains can produce significant Karst Fen-beaver wetland complexes. Depending on valley shape, size, and discharge volume, many Karst Fen-beaver wetland complexes should be considered perennial ecosystem complexes, rather than transient elements. In some rare cases, fens located in upland drainageway floodplains can receive seasonal floodwater.

Wetland description

Fen ecosystems are often geographically isolated and occur as minor components within a larger habitat matrix (Amon et al. 2002). In 2001, the Supreme Court removed wetlands considered "isolated" or "non-navigable" from Waters of the United States (WOTUS), unless they could be proven to be connected through a "significant nexus" (Mushet et al. 2015). Since then there has been debate on the legal interpretation of the WOTUS and whether geographically isolated wetlands fall under the definition. Wetlands subject to federal protections (i.e., jurisdictional wetlands) have typically been restricted to navigable streams and portions of floodplains that receive surface water flooding (Bedford and Godwin 2003). At this time, this definition does not include wetlands like Karst Fens that are in smaller order streams, not directly adjacent to a channel, and are maintained by saturated soils from groundwater. As a result, Karst Fens and fens in general are at a greater risk of degradation and loss. Recent research highlights the connectivity and ecological contributions that these wetlands provide and why they should be protected, and may support future changes to the WOTUS (Marton et al. 2015, Cohen et al. 2016, Rains et al. 2016, Golden et al. 2017).

This loophole in wetland protection partially originates from how we classify and define wetlands using the US Fish and Wildlife Service's National Wetlands Inventory (NWI). Traditionally, NWI units are based on the three attributes: hydrophytic plants, hydric soils, and hydrology (Cowardin and Golet 1995). This hierarchal approach has been useful in mapping wetlands across the country, but it has been challenging to effectively classify fens. Historically, The NWI system has been focused on surface water influenced wetlands and did not account for fens influenced by groundwater discharge and the unique ecosystems produced by karst topography. While biologists have used the NWI classification to aid in finding previously unknown fens, categories that may point toward fens include a range of other wetland types.

Hydrogeomorphic classification systems (HGM) by the US Army Corps of Engineers were later developed to better understand ecological interactions and distinctions of wetland functional capacities (Brinson 1993a). The HGM classification system highlights the relationship between water source, hydrodynamics, and geomorphic setting. In this scheme, fens and seeps are defined as being developed by groundwater on slopes (Brinson 1993b). Additional modifiers were later added to the NWI system to acknowledge abiotic interactions involving landscape position, landform, water flow path, and waterbody (Tiner 2003b). Missouri’s NWI system hasn’t been updated since the 1990s, and these additional descriptors that account for groundwater-fed wetlands are not part of the current dataset.

Soil features

Unique soils, rich in nutrients develop on Karst Fens and can be quite variable. Dark-colored, carbon-rich surfaces with gray-colored subsurfaces typify most fens. Resulting from near permanent saturation, these ecological sites do not completely cycle organic matter which results in distinctive zones of carbon accumulation at the surface. These darkened surface horizons can have mineral, organic, or mucky mineral soil materials. Organic parent materials are developed in place by decomposed herbaceous plant materials and represent the wettest conditions. Mineral parent materials include sediments that were deposited either by hillslope processes from the uplands above (colluvium) or those that were deposited by floodwaters (alluvium).

There are locations within many fens that have all three of parent material types in one soil profile. For non-organic, mineral surface horizons, during the hundreds to thousands of years following deposition as colluvium or alluvium, completely decomposed herbaceous plant matter became incorporated into the soil, producing a rich, black color. In some cases, the organic matter content is so high within a mineral soil horizon that it can develop a mucky mineral intergrade. Below the dark surface horizons of most profiles is a sharp boundary to a gray-colored subsoil. These gray-colored horizons are permanently saturated and as a result depleted of iron, which produces their gray color. Soil textures in mineral surface horizons are often loamy with moderate amounts of sand, whereas the gray-colored subsurface horizons often bottom out in old gravel bar deposits high in sand and chert gravel.

Dark-colored, carbon-rich surfaces with gray-colored subsurfaces typify most karst fens. Resulting from near permanent saturation, these ecological sites do not completely cycle organic matter which results in distinctive zones of carbon accumulation at the surface. These darkened surface horizons can have mineral, organic, or mucky mineral soil materials. Organic parent materials are developed in place by decomposed herbaceous plant materials and represent the wettest conditions. Mineral parent materials include sediments that were deposited either by hillslope processes from the uplands above (colluvium) or those that were deposited by floodwaters (alluvium). There are locations within many fens that have all three of parent material types in one soil profile. For non-organic, mineral surface horizons, during the hundreds to thousands of years following deposition as colluvium or alluvium, completely decomposed herbaceous plant matter became incorporated into the soil, producing a rich, black color. In some cases, the organic matter content is so high within a mineral soil horizon that it can develop a mucky mineral intergrade. Below the dark surface horizons of most profiles is a sharp boundary to a gray-colored subsoil. These gray-colored horizons are permanently saturated and as a result depleted of iron, which produces their gray color. Soil textures in mineral surface horizons are often loamy with moderate amounts of sand, whereas the gray-colored subsurface horizons often bottom out in old gravel bar deposits high in sand and chert gravel.

Specifically, this ecological site is correlated to the Beefork Series. The Beefork series consist of very deep, very poorly drained soils fed by springs and formed in a mantle of organic material and underlying gravelly to extremely gravelly colluvium and alluvium. These nearly level to gently sloping soils occur mainly in upland drainageways on terraces, toeslopes and footslopes within the Ozark Highlands. Slopes range from 0 to 12 percent. The mean annual soil temperature is 13 degrees Celsius (56 degrees Fahrenheit). Mean annual precipitation is about 1,067 millimeters (42 inches).

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Organic material

(2) Colluvium – limestone and dolomite (3) Alluvium |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Mucky, peaty silt loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Very poorly drained to poorly drained |

| Permeability class | Moderately slow |

| Soil depth | 60 – 80 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 1% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-80in) |

27 – 28 in |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-80in) |

6.5 – 7.2 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (0-80in) |

75% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (0-80in) |

10% |

Ecological dynamics

Karst Fens are unique compared to fens from other Midwestern states, which occur in prairie landscapes where subsurface water percolates through calcareous glacial materials until it becomes perched, discharging on a variety of slope types. In comparison, Karst Fens occur within an unglaciated forest-woodland landscape and have a complicated hydrogeologic (karst) setting. Groundwater percolates through deep, weathered residuum, eventually contacting calcareous, dolomitic bedrock that produces shallow aquifers. Mineral-rich groundwater discharges where upland slopes meet valley bottoms, producing the Karst Fen environment. Karst Fens begin to show up at the first sign of groundwater discharge within a watershed. Thus, the potential for a fen occurrence is limited to a hydrologic window occurring between karst uplands with adjacent losing stream valleys high in a watershed, and river breaks landscapes with large perennial river systems below. While they can occur as larger units (> 4 acres in size), they typically represent minor components of narrow valleys above major floodplains. Although small in acreage they are comparatively frequent in number. They are most common in the uppermost, gaining sections of the Current, Black, Meramec, Osage, and Gasconade River watersheds along 1st and 2nd order streams.

The plant communities of Karst Fens are exceptionally biodiverse and are classified by NatureServe as imperiled (Table 1, 2000). This reflex the variable soils and complex hydrodynamics of these sites. Subtle differences in landform and elevation affect the depth and duration of the water table, and thus plant community structure and composition. High-functioning Karst Fen ecological sites are dominated by sedges, grasses, and forbs and are typically void of significant tree and shrub cover. Species unique to calcium-rich environments, such as orange coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida var. umbrosa) and those disjunct from their typical range, such as bristlystalked sedge (Carex leptalea) help define plant communities. The latter are thought to be relicts of previous climatic periods that have remained in the stable, Karst Fen ecosystem. Water table fluctuations produce variable plant community dynamics. In drier areas, species like little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) may be present and resemble a mesic tallgrass prairie. In moderately wet sites, species like ??? and ??? are often common. In the wettest areas, species like swamp lousewort (Pedicularis lanceolata) and whorled loosestrife (Lysimachia quadrifolia) occur. Most Karst Fen plant communities are highly degraded and can be difficult to discern based on vegetation. Species like Dudley’s rush (Juncus dudleyi) and golden ragwort (Packera aurea) are common species that occur in a variety of wetland types in the region but are highly correlated to both intact as well as degraded Karst Fens. As unique/disjunct species disappear from these degraded locations their flora reflect more general Midwestern wetland community assemblages.

Karst Fens, although infrequent and small in size are centers of biodiversity and have specialized ecosystem connections. The reliance of species like the Hine’s emerald dragonfly (Somatochlora hineana) epitomize this. Other relationships with animal species such as the North American beaver (Castor canadensis) provide additional ecological complexity by adding areas of carbon-rich (vs mineral-rich), stagnant-water marshes with different nutrient cycle dynamics. Beaver-modified fens provide a unique dynamic to the karst-fen-floodplain by creating additional suite of ecological conditions for flora and fauna.

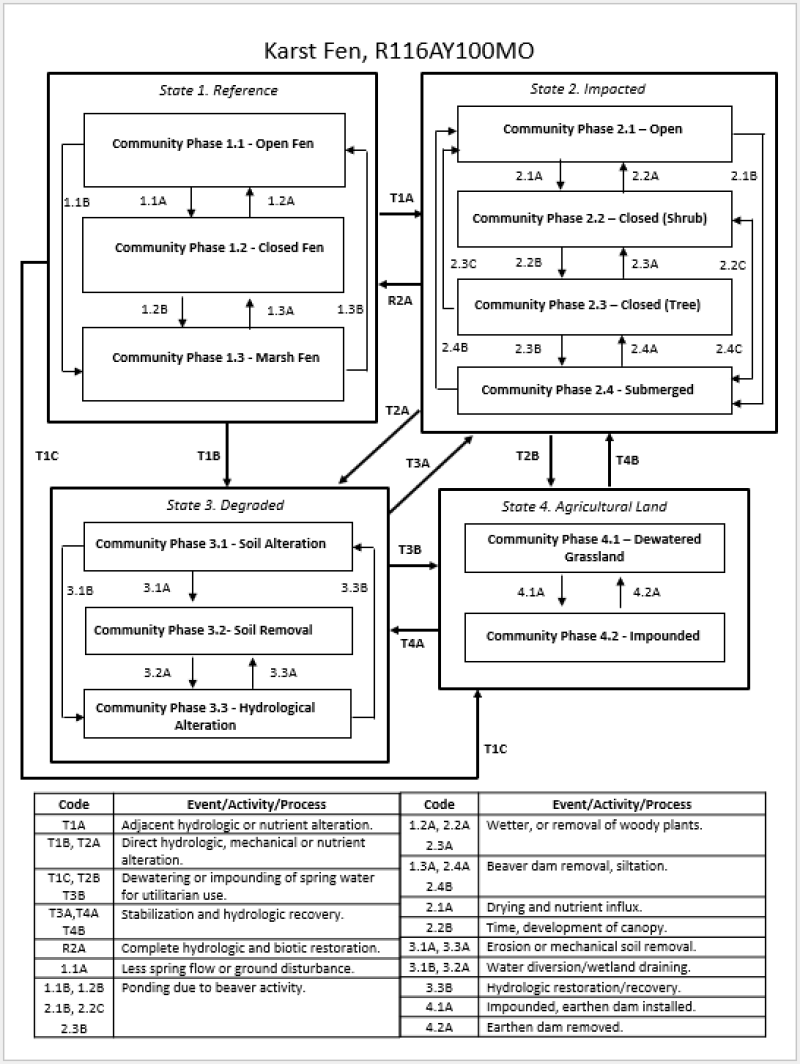

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

| T1A | - | Adjacent hydrologic or nutrient alteration |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Direct hydrologic, mechanical or nutrient alteration. |

| T1C | - | Dewatering or impounding of spring water for utilitarian use. |

| R2A | - | Complete hydrologic and biotic restoration |

| T2A | - | Direct hydrologic, mechanical or nutrient alteration. |

| T2B | - | Dewatering or impounding of spring water for utilitarian use. |

| T3A | - | Stabilization and hydrologic recovery. |

| T3B | - | Dewatering or impounding of spring water for utilitarian use. |

| T4B | - | Stabilization and hydrologic recovery. |

| T4A | - | Stabilization and hydrologic recovery. |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

| 1.1A | - | Less spring flow or ground disturbance |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1B | - | Ponding due to beaver activity |

| 1.2A | - | Wetter, or removal of woody plants. |

| 1.2B | - | Ponding due to beaver activity |

| 1.3A | - | Beaver dam removal, siltation. |

State 2 submodel, plant communities

| 2.1A | - | Drying and nutrient influx |

|---|---|---|

| 2.1B | - | Ponding due to beaver activity |

| 2.2A | - | Wetter, or removal of woody plants. |

| 2.2B | - | Time, development of canopy. |

| 2.2C | - | Ponding due to beaver activity |

| 2.3A | - | Wetter, or removal of woody plants. |

| 2.3B | - | Ponding due to beaver activity |

| 2.4B | - | Beaver dam removal, siltation. |

| 2.4C | - | Beaver dam removal |

| 2.4A | - | Beaver dam removal, siltation. |

State 3 submodel, plant communities

| 3.1A | - | Erosion or mechanical soil removal |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1B | - | Water diversion/wetland draining. |

| 3.2A | - | Water diversion/wetland draining. |

| 3.3B | - | Hydrologic restoration/recovery |

| 3.3A | - | Drying of fen, removal of organic soils |

State 4 submodel, plant communities

| 4.1A | - | Levees or earthen dams construction |

|---|---|---|

| 4.2A | - | Earthen dam removed |

State 1

Reference State

The reference state includes numerous community phases related to the hydrology of the site. Community phase 1.1 is the open fens with minerotrophic conditions, low available nitrogen and phosphorus, and permanent soil saturation, but not permanent inundation found on base of toe slopes, foot slopes and side slopes. Community phase 1.2 which is the shrub fen that are too small or broken up within a drier forested matrix to maintain an open canopy. Community phase 1.3 Marsh fen which form below open or closed fens in locations where water becomes ponded. Marsh fens are open communities dominated by herbaceous emergent aquatic vegetation.

Dominant plant species

-

inland sedge (Carex interior), grass

-

woollyfruit sedge (Carex lasiocarpa), grass

-

elliptic spikerush (Eleocharis elliptica), grass

-

orange coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida), other herbaceous

-

common sneezeweed (Helenium autumnale), other herbaceous

-

whorled yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia quadrifolia), other herbaceous

-

stiff cowbane (Oxypolis rigidior), other herbaceous

Community 1.1

Open Fen

Figure 7. Example of Community 1.1 Reference Open Fen. Susan Mahans fen with Riddells goldenrod snd asters.

Stable reference state community dominated by sedges and forbs. Disjunct and highly conservative (specialist) plant species are characteristic and indicative of this state, as is a lack of or low incidence of generalist species. Many species are also considered relicts from previous climatic periods. Stability in this phase is maintained by mineral-rich conditions, low available nitrogen and phosphorus, and permanent soil saturation by laterally-moving groundwater discharge (but not by inundation or ponding). There are two main expressions of open fen. Those that form where groundwater discharges from a footslope (and sometimes, side slope) and those where groundwater discharges from the base of a toe slope. Open fens at the base of toe slopes often transition into a 1.3 Marsh Fen some distance from the groundwater source. Open fens on footslopes and side slopes are more hydrologically isolated and have well defined margins. Representative species: Orange coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida var. umbrosa), Common sneezeweed (Helenium autumnale), Inland sedge (Carex interior), Prairie Loosestrife (Lysimachia quadrifolia), Cowbane (Oxypolis rigidior), Ellipitic spikerush (Eleocharis elliptica), and Wiregrass Sedge (Carex lasiocarpa)

Community 1.2

Closed Fen

Figure 8. Community phase 1.2 at Frank Rough Hollow backslope.

Reference state community closed fens consist of fens and seeps that are too small (embedded) or too broken up (marbled) within a drier forested matrix. This allows adjacent drier site conditions to develop forest canopies that impact the fen. Examples include fens slopes (often referred to as “hanging fens”) or at the base of slopes. Small depressions, such as narrow abandoned channels with groundwater discharge can also fall within this category if the adjacent upland or bottomland forest canopy overhangs these small natural communities. Representative species: Orange coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida var. umbrosa) False Nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica), Golden Ragwort (Packera aurea), Dudley’s Rush (Juncus dudleyi), Emery’s Sedge (Carex emoriyi), and Leafy Bulrush (Scirpus polyphyllus)

Community 1.3

Marsh Fen

Figure 9. Community 1.3 Marsh Fen at Kyle Hodge hollow.

Marsh fens form below open or closed fens in locations where water becomes ponded. Marsh fens are open communities dominated by herbaceous emergent aquatic vegetation. The ponding of water shifts the plant away from fen specialists (1.1) to more wetland generalists. This is because instead of being a “through-flow” system of saturated soils, the ponding of water, which may seasonally fluctuate, changes the water chemistry and increases the nutrient availability. Greater nutrients shift the plant community towards species capable of using the excess nutrient towards more vigorous growth. These species are typically more resilient to variable water levels and are representative of wetland plant generalists. Within karst fen complexes, the marsh fen state typically forms in floodplains or terraces adjacent to streams. The contribution of surface water in these locations can also contribute to differences in water chemistry and plant community. Historically, beaver impoundments likely contributed to dynamics of this community’s condition. The interaction of beaver, overland flow, and soils within abandoned channels or other floodplain depressional features could also contribute to the presence of this community phase. Representative species: Orange coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida var. umbrosa) Common sneezeweed (Helenium autumnale), Cowbane (Oxypolis rigidior), Interior Sedge (Carex Interior), Porcupine Sedge (Carex hystericina), Broadleaf Cattail (Typha latifolia), and Georgia Bulrush (Scirpus georgianus)

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Less spring flow or ground disturbance

Context dependence. This pathway occurs when the volume/rate of groundwater seepage decreases below the threshold needed to maintain an open canopy. This change in hydrology influences the footprint of the site.

Pathway 1.1B

Community 1.1 to 1.3

Ponding due to beaver activity

Context dependence. This pathway occurs following ponding of groundwater discharge through beaver activity. The increased water could be received from multiple hydrologic sources (riverine and groundwater seepage).

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Wetter, or removal of woody plants.

Context dependence. This pathway occurs when the volume/rate of groundwater discharge increases to the point of prohibiting woody vegetation due to soil saturation and nutrient deficiency. The increased volume of water would need to be distributed across a large enough area to simultaneously increase the footprint of the community to open the canopy but not create a permanently inundated state (1.3). In conjunction with the soil moisture regime, periodic fire of the adjacent woodlands could potentially keep woody encroachment at bay along the periphery. Fire intensity, frequency, and relationship with groundwater discharge is unknown.

Pathway 1.2B

Community 1.2 to 1.3

Ponding due to beaver activity

Context dependence. This pathway occurs following ponding of groundwater discharge through beaver activity. The increased volume of water would need to be distributed across a large enough area so as to simultaneously increase the size of the community, open the canopy, and create a permanently inundated state. Another option would be for the volume/rate to remain the same, but an impediment to flow could change the hydrology from flow-through to a ponded condition. This could occur from beaver activity, road construction, or levee construction.

Pathway 1.3B

Community 1.3 to 1.1

Beaver dam removal

Context dependence. This pathway occurs following the removal of beaver dam or other impoundments resulting in restoration of wetland footprint as defined by rate/volume of karst groundwater discharge. The site begins to function more as “through-flow” saturated state again. The slow loss of water, often occurring in conjunction with a buildup of organic matter, creates conditions suitable for the specialized non-aquatic wetland vegetation indicative of an open fen (1.1). Abandoned beaver dams and/or those breached during extreme precipitation events are protential pathways in which this transition occurred within fen complexes of Ozark stream valleys. Excommunication of beavers or extreme rain events are the most likely causes. In the case of an extreme rain event, this can be a rather swift transition, whereas extirpation of beavers would be much slower.

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.2

Beaver dam removal, siltation.

Context dependence. This pathway occurs following the removal of beaver dam or other impoundments resulting in restoration of wetland footprint as defined by rate/volume of karst groundwater discharge. This condition is often concomitant with siltation, effectively lowering the water table and increasing the likelihood of woody invasion. Excommunication of beavers or extreme rain events are the most likely causes. In the case of an extreme rain event, this can be a rather swift transition, whereas extirpation of beavers would be much slower.

State 2

Impacted State

These conditions result from negative impacts that are not so extensive as to significantly mechanically alter the soil structure of the site. Examples include over-grazing, significant alterations to the vegetation structure and composition, and minor alterations to hydrology. Many remnant Karst Fen sites are currently in the Impacted State. These sites often retain some biological legacies from 1.1 Open Fen, but many/most of the highly specialized species are gone.

Dominant plant species

-

Georgia bulrush (Scirpus georgianus), grass

-

rice cutgrass (Leersia oryzoides), grass

-

common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum), other herbaceous

-

groundnut (Apios americana), other herbaceous

-

Baldwin's ironweed (Vernonia baldwinii), other herbaceous

Community 2.1

Open

Figure 10. Community Phase 2.1 at Kyle Beek Fork, a private land fen remnant with surrounding pasture.

This phase is characterized as a stable open herbaceous community dominated by the subordinate generalist species that are often rare to absent in the reference condition. This is likely due to an influx of nutrient availability and general changes/stressors to the ecosystem. Other generalist wetland species colonize as well. Rapid negative impacts to the stable matrix of an open fen (1.1) can result in this degraded open alternate state. It is possible that a drained marsh fen could restabilize in this state as well. These sites are considered fen remnants. Representative species: Georgia Bulrush (Scirpus georgianus) Common Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum), Groundnut (Apios americana), Rice Cutgrass (Leersia oryzoides), and Baldwin’s Ironweed (Vernonia baldwinii)

Community 2.2

Shrub Closed

Figure 11. Community Phase 2.2 Shrub Closed at Frank Bee Fork.

This phase is characterized as having a prevalence of generalist wetland shrub species forming dense thickets with low or no herbaceous richness or structure. This phase is more likely to result from damaged closed and marsh fens than from open fens and is mostly the result of more damaging impacts than those that result in phase 2.1 conditions. Removing the conservative woody vegetation from a closed fen or draining a marsh fen could result in this phase. Lowering of the water table and nutrient influx could also produce this situation. Representative species: More generalist species including Coastal Plain Willow (Salix caroliniana), Hazel Alder (Alnus serrulata), Northern Spicebush (Lindera benzoin), Georgia Bulrush (Scirpus georgianus), Limestone Meadow Sedge (Carex granularis), and Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis). Fewer conservative species present. Smallspike False Nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica) and Leafy Bulrush (Scirpus polyphyllus) are likely absent.

Community 2.3