Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F121XY001KY

Shallow Limestone Residuum Backslopes

Accessed: 12/22/2024

General information

Approved. An approved ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model, enough information to identify the ecological site, and full documentation for all ecosystem states contained in the state and transition model.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 121X–Kentucky Bluegrass

The project area lies within the Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) 121 as designated by USDA-NRCS. Central Kentucky makes up 83 percent of the MLRA with the remaining acreage in Ohio (11 percent) and Indiana (6 percent). Total MLRA size is 10,680 square miles or 27,670 square kilometers. The majority of the MLRA is in the Lexington Plain section of the Interior Low Plateaus province of the Interior Plains. Elevations in MLRA 121 range from about 430 feet (on the Ohio River) to approximately 1,100 feet.

The Bluegrass physiographic region, which includes much of MLRA 121, is restricted to the central portion of Kentucky where Ordovician (and some Silurian, and Devonian) age rocks are exposed at the surface. The rolling hills of this area are caused by the weathering of limestone that has been pushed up along the crest of the Cincinnati Arch. Younger geologic units occur along the eastern and western edges of the Bluegrass Region and are typified by thin-bedded shale, siltstone, and limestone.

Classification relationships

National Vegetation Classification. The community described in this ecological description also relates to the Interior Plateau Chinkapin Oak-Shumard Oak Forest, Identifier CEGL007808 in the NatureServe Explorer Database.

Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission has identified 15 Forest Communities in Kentucky. This ecological site closely relates to KSNPCs "Calcareous sub-xeric forest".

The U.S. Forest Service has developed ecological regions and the soils covered under this ESD are found the following USFS Ecological Units of the Eastern United States:

Domain: # 200- Humid Temperate; Division: Hot Continental; Province: #222 -Eastern Broadleaf Forest (Continental) Province; Sections: #222F - Interior Low Plateau, Bluegrass, #222Fa - Outer Bluegrass Subsection, #222Fb - Inner Bluegrass Subsection, #222Fc - Western Bluegrass Subsection, #222Fd - Northern Bluegrass Subsection.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also has delineated ecological regions. This ESD lies within the following EPA designated areas: Level 1-Ecological Region #8.0 - Eastern Temperate Forests; Level 2 - #8.3 – Southeastern US Plains; Level 3 - #71 -Interior Plateau; Level 4 - #71l - Inner Bluegrass; #71d – Outer Bluegrass, #71k – Hills of the Bluegrass.

This community also related to the "Shumard oak-chinkapin oak-ash-elm" Upland Forest Type as identified by Ecologist Julian Campbell based on nutrient states cross referenced to xeric & seral sites.

Ecological site concept

This ecological site is defined by the shallow limestone soils found on hillsides and ridges in the Bluegrass physiographic region of Kentucky. The plant communities found on these sites are influenced by parent material and the well-drained to somewhat excessively-drained soils. The ecological site reference community is typified by chinkapin oak, Shumard’s oak, hickories, sugar maple, blue ash, white ash, and elm. The minor composition differences in this community will depend on many factors including soil depth, which ranged from 10 to 20 inches for sites evaluated under this ecological site description. Other influencing factors are the amount of rock content in the soil profile, surface rock, aspect, soil texture and structure, and presence of seeps, and rock outcrops. Some sites below 20 percent are unmanaged or minimally managed pasturelands. Most of the remaining woodlands are second or third growth with little management.

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Quercus muehlenbergii |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Ageratina altissima |

Physiographic features

These ecological sites are found on hillsides and narrow ridges in the Inner and Outer Bluegrass regions on hillsides and ridges generally ranging from 12 to 60 percent slopes. The major influencing geologic formation is Lexington limestone. Soil depth ranges from 10 to 20 inches over limestone bedrock or interbedded limestone and calcareous shale. Approximate site elevations range from 450 feet to 1,100 feet.

There is no water table, flooding or ponding on these sites as the runoff class is high and very high. Due to slope and slow permeability, these sites generate rapid runoff.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hill

(2) Ridge |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 137 – 436 m |

| Slope | 6 – 60% |

| Water table depth | 152 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The average annual precipitation in this area is 45 to 55 inches. Approximately 60 percent of the precipitation falls during the freeze-free period, and thunderstorms are common in the spring and summer months, producing lightning and high winds. The freeze-free period averages 210 days and ranges from 190 to 230 days, increasing in length to the south. The longest freeze-free periods are along the Ohio River. Most of Kentucky is in the USDA hardiness zone 6b. The warmest month of the year is July with an average maximum temperature of 85.90 degrees Fahrenheit, while the coldest month of the year is January with an average minimum temperature of 24.10 degrees Fahrenheit. Temperature variations between night and day tend to be moderate during summer with a difference that can reach 20 degrees Fahrenheit, and fairly limited during winter with an average difference of 17 degrees Fahrenheit. The annual average precipitation is 45.91 inches. The wettest month of the year is July with an average rainfall of 4.81 inches.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 210 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 187 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 1,270 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 4. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 5. Annual average temperature pattern

Influencing water features

This ecological site does not have any influencing water features.

Soil features

This ecological site is defined by the shallow limestone soils found on hillsides and ridges in the Bluegrass physiographic region of Kentucky. The plant communities found on these sites are influenced by parent material and the well drained to somewhat excessively drained soils.

The reference community is characterized by chinkapin oak, Shumard’s oak, shagbark hickory, sugar maple and elm. Blue ash is abundant on some sites. The minor composition differences in this community will depend on many factors including soil depth, which ranged from 10 to 20 inches for sites evaluated under this ecological site description. Other influencing factors are rock content in the soil profile, surface rock, aspect, soil texture and structure, and presence of seeps and/or rock outcrops. Some sites below 20% are unmanaged or minimally managed pasturelands. Most of the remaining woodlands are second or third growth woodlands with little to no management.

This ecological site is associated with Fairmount (clayey, mixed, active, mesic Lithic Hapludolls) and Cynthiana (clayey, mixed, active, mesic Lithic Hapludalf) soils in the Bluegrass physiographic region of Kentucky. These soils are shallow (less than 20”) to limestone and calcareous shale bedrock parent materials. They tend to be fertile due to these parent materials and adequate cation exchange capacity is associated with their clay contents. Available water holding capacity is variable depending on position on the landscape. Locations on steeper slopes or at the lower end of the range of soil depths can be relatively limited in their ability to supply water to plants during the growing season.

Sites mapped as rock land and/or rock outcrop-Fairmount complex, 50 to 120 percent slopes do not fit the concept of this ecological site description as differences in vegetation type and quantity were observed. Fairmount and Cynthiana soil components found in these excluded map units eventually will be revised and included in a different ecological site description.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

limestone

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Flaggy silty clay loam (2) Channery silty clay (3) Very flaggy sandy loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Clayey |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow to moderately slow |

| Soil depth | 30 – 53 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 25% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0 – 25% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

4.32 – 7.62 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

0% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

6.5 – 7.5 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 10% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 26% |

Ecological dynamics

Site Characteristics:

This ecological site is characterized by rocky, well drained to excessively drained shallow soils, and steep slopes. Most sites are best suited for timber production, wildlife habitat, or recreational uses, although lower sloping lands can be utilized as pasture. Most sites visited were unmanaged, lower-quality woodlands that had been cut over multiple times; however, some high-quality mature sites still exist in public and privately-owned protected areas.

Typical tree species include chinkapin oak, Shumard’s oak, white oak, hickories (mockernut, shagbark, pignut), sugar maple, ashes (white, blue) and elms (American, slippery). The exact composition of the community will depend on many factors including soil depth, slope, rock content, soil texture and structure, and presence of seeps and rock. The native plant understory was diverse but not dense, and there was no substantial shrub layer.

States and Phases:

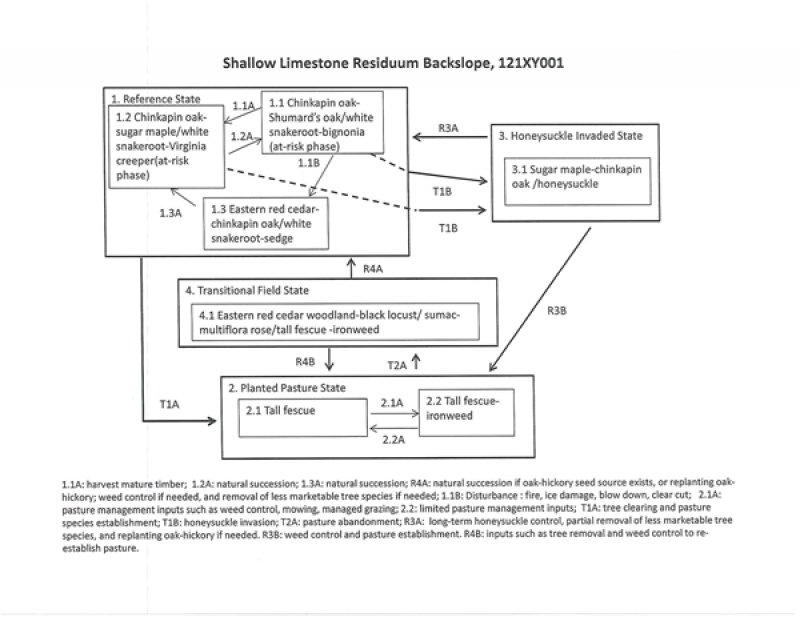

There are three phases in state 1, the reference community. Phase 1.1 is a mature, stable oak-hickory community. Phase 1.2 is a less mature mixed hardwood community that includes a greater component of sugar maple. Phase 1.3 is an eastern red cedar dominated successional stage with hardwood seedlings and samplings present. Disturbances such as selective timber harvest, wind and ice damage, or clear cutting will transition this phases with the reference state. The invasion of the aggressive non-native plant, Amur or bush honeysuckle can quickly transition phases 1.1 or 1.2 to an altered state. Complete tree removal and conversion to pastureland is feasible for few sites under this ecological site description due to steep slopes, shallow and droughty soils and high rock content. However, on sites conducive to pasture, a transition from state 1 to state 2 can be accomplished. State 4 includes a transitional phase, a pasture encroached upon by eastern red cedar and hardwood tree species. Oak and hickory regeneration may occur assuming there is still a viable seed source for these species on site or adjacent to the site. For pastureland (state 2) to successfully transition to the reference community (state 1), it is essential that a viable seed source exists for native tree and herbaceous species. Long-term pasture locations may need extensive restoration including seeding, planting, weed control, and timber stand improvement to achieve a full transition to state 1. Movement from a honeysuckle dominated woodland (state 3) back to state 1 can be accomplished but requires extensive inputs over a multi-year period.

Communities at Risk:

One of the greatest threats to this ecological site is the invasive plant commonly referred to as bush honeysuckle. Although this term is used to describe many different honeysuckle species, the most common bush honeysuckle found on these ecological sites was Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii). These plants reproduce through seed and a single plant can produce approximately one million berries in one season. Adapted to a wide range of habitats and light conditions, honeysuckle out competes native woodland plants including oak-hickory seedling and can quickly dominate woodlands. Most plants grow to a height of approximately 15 feet effectively shading the entire forest floor. This invasive plant is changing the fundamental composition and associated ecological functions of Kentucky's native woodland communities. Decades of honeysuckle growth have resulted in substantial losses in forest regeneration, wildlife habitat, and native plant species. Prevention and immediate early control of honeysuckle is strongly recommended as once the invasive plant is well established, landowners are faced with an expensive and long-term management challenge.

Forestry Management Considerations:

Since most of the sites under this ecological site description are woodlands, forestry management considerations are important. Careful pre-planning is recommended prior to any timber harvesting on these ecological sites, as the implementation of best management practices is essential to minimize soil erosion and impacts to water quality. A timber harvest plan should also include practices that provide protective measures to prevent the introduction and spread of invasive species such as bush honeysuckle. Landowners must be aware that the shallow bedrock on these sites makes construction of haul roads and log landings more costly and difficult, and that steep slopes will create operating challenges for mechanized equipment. Surface rock can also greatly restrict the use of machinery on many of these sites.

The utilization of fire in the management of Kentucky's oak woodlands is also relevant. In historically oak-dominated forests of the eastern U.S., prescribed fire is now commonly utilized as a management technique to increase understory light, suppress non-native plant species, and encourage successful oak regeneration. Decades of extensive research on this subject exists; however, the use of fire as a management tool in Kentucky woodland ecosystems is not without controversy. Fire may indeed be a valuable tool to foster oak regeneration on some sites, but it is by no means a simple or universal management technique appropriate for all oak woodlands.

In a 2008 University of Kentucky-Department of Forestry dissertation, Ms. Heather Alexander’s research conducted in Kentucky suggested that upland oak seedlings do not necessarily respond well to low-intensity prescribed burns, especially during the early growing season. Her conclusions were, “prescribed fire is often used to … encourage oak establishment and growth, but the efficacy of this strategy remains questionable.” Ms. Alexander’s work provided evidence that low intensity prescribed fire alone may not play a large role in encouraging oak regeneration, and that repeated burning had significant negative effects on survival and growth of both red and white oaks. Landowners and land managers should be aware of site-specific research such as this prior to utilizing fire as a management tool on these ecological sites.

Historical Perspective:

The Bluegrass was the first of Kentucky’s regions to be intensively settled and woody vegetation of various compositions covered the majority of the region before settlement. A grass species, Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), provided the region with its common name, and although the exact introduction of Poa pratensis to the region is obscure, the grass was likely was introduced by European settlers. (Campbell 1985). Many attempts at describing the original vegetation in the Inner and/or Outer Bluegrass have been made by Davis (1927), McInteer (1941), Braun (1950), Davidson (1950), Wharton and Barbour (1973), and Campbell (1985).

Based in the Lexington, KY area, ecologist Julian J.N. Campbell has compiled extensive records and historical accounts of early Bluegrass vegetation. These accounts, many from the 1700-1800’s, provide evidence that the region was mostly covered by forests. An early explorer of Kentucky, Filson (1784) wrote, “The country in general may be considered as well timbered, producing large trees of many kinds, and to be exceeded by no country in variety.” Drake (1840s re.1794) described land in Mason County as “covered with an unbroken forest” consisting “chiefly of blue ash – tall, straight." Parry (1794) wrote that land in Bourbon County was “first quality” and contained “walnut, cherry, blue-ash, buckeye, locust and hackberry." Today’s Inner and Outer Bluegrass regions are predominately managed pasture for horses and cattle, urban development, and row crops interspersed by relatively small blocks of private and publically owned woodlands. For example, Woodford, Fayette, Mercer and Bourbon counties have 3 to 18 percent of their acreage remaining in woodlands. (Kentucky Division of Forestry, 2009).

A unique historical vegetative characteristic of the Bluegrass was the existence of extensive canebrakes areas (Arundinaria gigantea (Walter) Muhl.), a bamboo species native to North America. Bluegrass canebrakes were recorded extensively in upland areas at the time of settlement; however, soils within this ecological site description are too shallow to support this specific vegetative community.

For example, in the Versailles, Kentucky vicinity, historical records from Graddy (1840s re.1788) stated that one “couldn’t find 10 acres of uncleared land that was not cane.” The locally known Cane Ridge in eastern Bourbon County was described by Finley (1840’s re.1790) as part of an “unbroken canebrake extending for twenty miles”. Traveling through what is now Madison county, Walker (1824 re.1775) wrote that he “traveled about thirty miles through thick cane and reed.”

Based on early records, pre-settlement forests in the Bluegrass region contained an abundance of woodland species now less common even in the remaining protected remnant forests. Blue ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata Michx.), Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus (L.)K. Koch), pawpaw (Asimina triloba (L.) Dunal) and Ohio buckeye (Aesculus glabra Willd.) are now reduced in number and location throughout the region. (Campbell. 1985).

State and transition model

Figure 6. ES-MLRA 121-Shallow Limestone Residuum Backslope S

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Shallow LImestone Oak-Hickory Forest

This state consists of three phases: mixed oak-hickory forest, oak-maple-hickory forest, and early successional eastern red cedar woodland. Common species for more mature forested sites are chinkapin oak (Quercus muehlenbergii Engelm.), white oak (Quercus alba L.), and Shumard’s oak (Quercus shumardii Buckley), and northern red oak (Quercus rubra L.). Black oak (Quercus velutina Lam.) may be present. Common hickory species are pignut (Carya glabra (Mill.) Sweet), mockernut (Carya alba (L.)Nutt.) and shagbark (Carya ovata (Mill.)K.Koch). Sugar maple (Acer saccharum Marsh.), white ash (Fraxinus americana L.), blue ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata Michx.), American elm (Ulmus americana) and slippery elm (Ulmus rubra) were also found on these sites. The understory community, in the absence of invasive non-native vegetation, consists of a moderately diverse but not dense understory of native woodland plants, leaf litter, and usually surface rock. A defined shrub layer was not present, and tree seedling and samplings were common.

Community 1.1

Shallow Limestone Oak-Hickory Forest

Figure 7. KYplotRivercliffs

Figure 8. KYdorman_rockoutcrop

Figure 9. KYplotH

Figure 10. KYplotKleber

Indicator species for this site included chinkapin oak (Quercus muehlenbergii Engelm.) and Shumard’s oak (Quercus shumardii Buckley). Shumard's oak is common throughout the Bluegrass region but virtually absent from the Appalachian section of Kentucky and infrequent in other parts of the state. White oak (Quercus alba L.) can also be found frequently on these sites. Other oaks present on this ecological site, but to a much lesser degree, are Northern red oak (Quercus rubra L.), and black oak (Quercus velutina Lam.). Monitoring plots in both the Inner and Outer Bluegrass physiographic regions displayed subtle differences in species preferences. Scarlet oak was not found and black oak was rarely found in monitoring plots within the Inner Bluegrass region. Northern red oak was found in both regions but only on the more protected sites. Hickories found on sites included pignut (Carya glabra), mockernut (Carya alba) and shagbark (Carya ovata). Pignut was common in monitoring plots in the Outer Bluegrass region and was less common in the Inner Bluegrass plots. Mockernut hickory grows throughout Kentucky and is commonly found on dry slopes/uplands. This species was found in multiple plots. With light, mobile, wind-blown seeds and a high tolerance to shade, maples and ashes were also predominate species. Sugar maple (Acer saccharum Marsh.), white ash (Fraxinus americana L.), and blue ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata Michx.) were recorded on all sites visited. Frequent in the Bluegrass region of Kentucky, the blue ash is usually found on limestone rock outcrops or shallow, rocky limestone soils. It is easily identified by distinctive, winged branches. Although greatly reduced in number from the turn of the century, this species can be found on the limestone cliffs along the Kentucky River and other limestone hillsides throughout the Bluegrass. American elm (Ulmus americana) and slippery elm (Ulmus rubra) were also found on these sites. The understory community for this phase included a light to moderate layer of native woodland plants and substantial leaf litter. Surface rock may be present. A well-defined shrub layer is not usually present. Successful regeneration of multiple tree species, including oak and hickories, was occurring in the understory.

Forest overstory. The overstory composition for this phase consists of chinkapin oak, Shumards oak, white oak, sugar maple, white ash, blue ash, shagbark hickory, mockernut hickory, American elm and/or slippery elm. Black oak, northern red oak, scarlet, and bitternut hickory were infrequent on these sites.

Forest understory. The typical understory composition for these sites are leaf litter, surface rock, and a light herbaceous layer of native Kentucky woodland plants such as snakeroot, bignonia (crossvine) agrimony, sedges, violets, ferns, spleenworts, grape,and Virginia creeper. Sites were protected from grazing, logging, and heavy recreational uses, so the understory was especially beautiful in the early spring when native wildflowers covered the forest floor. A well-defined shrub layer was not present. Understory seedling and/or sapling trees included sugar maple, elms, ashes, oaks, and hickories. Cedar seedlings scattered on site. Ohio buckeye, eastern red cedar, and slippery elm were not uncommon.

Table 5. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 1-2% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 1% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 1% |

| Forb basal cover | 1% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0-1% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 30-55% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 1-5% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 5-10% |

| Bedrock | 0-15% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 10-15% |

Table 6. Woody ground cover

| Downed wood, fine-small (<0.40" diameter; 1-hour fuels) | 1-1% |

|---|---|

| Downed wood, fine-medium (0.40-0.99" diameter; 10-hour fuels) | 1-2% |

| Downed wood, fine-large (1.00-2.99" diameter; 100-hour fuels) | 1-1% |

| Downed wood, coarse-small (3.00-8.99" diameter; 1,000-hour fuels) | 1-2% |

| Downed wood, coarse-large (>9.00" diameter; 10,000-hour fuels) | 1-5% |

| Tree snags** (hard***) | – |

| Tree snags** (soft***) | – |

| Tree snag count** (hard***) | 0-2 per hectare |

| Tree snag count** (hard***) | 0-2 per hectare |

* Decomposition Classes: N - no or little integration with the soil surface; I - partial to nearly full integration with the soil surface.

** >10.16cm diameter at 1.3716m above ground and >1.8288m height--if less diameter OR height use applicable down wood type; for pinyon and juniper, use 0.3048m above ground.

*** Hard - tree is dead with most or all of bark intact; Soft - most of bark has sloughed off.

Table 7. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 1-5% | 1-5% | 1-5% | 2-25% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 1-10% | 5-10% | 1-10% | 5-15% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 5-15% | 5-15% | 1-15% | 2-15% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 5-15% | 1-5% | – | – |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 5-15% | 0-5% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | 5-20% | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | 50-70% | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | 30-50% | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Community 1.2

Shallow Limestone Oak-Maple Forest

Figure 11. chinkapin-maple-elm community on Fairmount mapunit

This phase is characterized by hardwoods overtopping the eastern red cedar of phase 1.3. Tree species include chinkapin oak, Shumard oak, white oak, sugar maple, white ash, blue ash, American elm, slippery elm, and hickories. Quick growing and shade-tolerant, sugar maple and ash are usually an important component of this phase. Removal of the hardwood trees will result in a transition back to phase 1.3 and a re-dominance of eastern red cedar. Once the hardwoods begin to completely overtop the cedars, shade mortality reduces cedar numbers allowing hardwood dominance and phase 1.3 will transition to phase 1.2. Phase 1.2 will transition with time phase 1.1 as the shallow, droughty, rocky limestone soils found on these specific sites favor oak-hickory dominance. Drought years will reduce the number of maples allowing mast species to favorably compete in the long-term.

Forest overstory. Overstory composition for this community consisted mainly of chinkapin oak, sugar maple, and Shumard oak. Some sites had white oak, mockernut hickory, shagbark hickory, and American elm. Sugar maple is a major component in this phase. Shade tolerant, adaptable, and quick growing, this species is very competitive on these ecological sites in non-drought years or in more protected sites. This phase had a higher sugar maple canopy cover, basal area, and regeneration rate than the other State 1 phases.

Forest understory. The understory composition for these sites includes leaf litter, usually some surface rock, and a diverse but not dense herbaceous layer of native Kentucky woodland plants such as snakeroot, bignonia (crossvine) agrimony, ticktrefoils, sedges, violets, ferns, spleenworts, frost or summer grape, and Virginia creeper. A well-defined shrub layer was not present on these sites. Understory seedling and sapling trees included sugar maple, elms, ashes, oaks, and hickories. Cedar seedlings were usually on site. Ohio buckeye, eastern red cedar, and slippery elm were not uncommon.

Table 8. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 1-1% | 1-3% | 1-3% | 5-15% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 1-5% | 1-2% | 1-10% | 5-15% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 1-5% | 1-5% | 1-10% | 2-10% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 5-25% | 0-1% | – | – |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 10-40% | 0-1% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | 10-45% | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | 50-70% | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | 10-50% | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Community 1.3

Shallow Limestone Cedar Woodland

Figure 12. Eastern red cedar grove -old fescue pasture-Fairmount soils

Figure 13. Fairmount hillside with previously cleared sites overtaken by eastern red cedar

Figure 14. Hardwoods overtopping cedars on Cynthiana soil

Rocky limestone soils are typified by successional communities of dense eastern red cedar. This community is the natural next step from the transitional field state (state 4). This phase also occurs where timber harvests have removed the overstory hardwoods or other disturbances (fire, wind damage, etc.) have occurred. Eastern red cedar prefers dry rocky hillsides and thrives in open fields, limestone glades, and limestone outcrops. Waiting for sunlight and release, multiple species of hardwood seedling and sapling are usually in the understory including sugar maple, white ash, white oak, chinkapin oak, red oaks, American elm, slippery elm, and hickories. Understory composition of oaks and hickories were dependent on available seed sources. This is an important consideration for landowners wishing to transition from either pasture or transitional field states. Long-term pasture may not have the desired oak and hickory seed sources on site and oak-hickory plantings may be necessary. Light, wind-blown seeds from sugar maple, elm, hackberry, and ash will naturally be present on most sites. Timber stand improvement activities may be recommended to favor regeneration of oak-hickory.

Forest overstory. This successional community is typified by an overstory composition of dense eastern red cedar. Cedars can thrive in the shallow, often droughty, soils included in this ESD and are the primary pioneer tree on abandoned farmland.

Forest understory. Due to shading, the forest understory composition of the shallow limestone cedar woodlands less diverse than phases 1.1 or 1.2. Phase 1.3 were often abandoned cool-season grass pastures, so fescue or other planted pasture grasses were still a major component of the understory for these communities.

Table 9. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 1-2% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 1% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 20-40% |

| Forb foliar cover | 1-5% |

| Non-vascular plants | 1% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 20-35% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-5% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 1-3% |

| Bedrock | 0-1% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 1-15% |

Table 10. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 0-1% | 0-1% | 1-5% | 1-1% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 1-2% | 0-1% | 5-10% | 1-3% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 1-5% | 0-1% | 5-25% | 1-3% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 1-10% | – | – | – |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 10-15% | – | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | 50-85% | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | 20-75% | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | – | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Selective harvest of the larger oak and hickory trees will shift this phase to 1.2. With the removal of mast species and the additional sunlight, sugar maple often increases. In some locations, sugar maple seedling and sapling can be dense.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Fence | |

| Access Control | |

| Tree/Shrub Site Preparation | |

| Tree/Shrub Establishment | |

| Forest Stand Improvement | |

| Forest Management Plan - Applied | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

Pathway 1.1B

Community 1.1 to 1.3

Disturbances such as logging will result in phase 1.1 moving to phase 1.3. Removal of hardwoods will open the canopy allowing the eastern red cedar to regenerate. Post disturbance management options include allowing regeneration throughout natural succession, direct planting of oak and hickory species and control of eastern red cedar, bush honeysuckle and invasive vegetation control, and forest and wildlife management planning based on landowner objectives.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Upland Wildlife Habitat Management | |

| Early Successional Habitat Development/Management | |

| Forest Stand Improvement | |

| Forest Management Plan - Applied |

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

This natural transition occurs during prolonged dry periods. Oak and hickory species typical for these sites are better adapted to surviving periods of drought compared to sugar maple. Unlike the moderately deep or deep soil sites which were visibly transitioning to sugar maple, the shallow, rocky soil sites described within this ecological site were still dominated by drought-resistant oaks and hickories on the majority of sites. These sites are at risk due to the invasion of bush honeysuckle (see transition T1.B).

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Forest Management Plan - Applied |

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.2

This phase consists of oaks, hickories, maples, elms, and ashes that have reached a height to overtop the eastern red cedars. The young trees have escaped the shaded environment of the red cedar canopy. Oak and hickory species numbers will depend on local seed sources while the light, windblown seeds of maples, ashes, and elms were often dense on monitored sites as these species are better adapted to growing under the dense shade of cedar. Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis L.) was frequently found in these mid-successional communities.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Fence | |

| Access Control | |

| Forest Stand Improvement | |

| Forest Management Plan - Applied | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

State 2

Planted pasture

This state varies greatly in species composition depending on management and specific site characteristics such as slope, rock content, and soil depth which can range between 10 to 20 inches. The pasture sites on Fairmount and Cynthiana mapunits were on lower slope sites. Pastures were predominately fescue (Festuca arundinacea). These shallow soil sites lie over limestone or limestone and calcareous shale parent material. They are droughty with moderately slow to slow permeability on slopes. Therefore, a good plant cover is needed at all times to reduce runoff and protect against soil erosion. Grazing should be regulated on sites to maintain a minimum plant height with periods of rest to allow adequate regrowth and avoid erosion.

Community 2.1

Managed pasture

Figure 15. Fairmount, min slope, mowed annually, mged graze

This community phase is characterized by a high level of management that includes some combination of seeding, mowing, fertilizing, controlled grazing, and weed control. Species and production levels varied greatly on the sites visited and were dependent on landowner objectives and management. Sites visited were mowed annually or bi-annually, fertilized periodically, usually had slopes of less than 15 percent, had little or no visible rock outcrops, and were predominately seeded in tall fescue. Managed sites were only found on a few lower slope areas where mechanical management was feasible. Production on these sites varied depending on specific site conditions, type of grass seeded, the level of use, and the type of management. Estimated pasture production levels for specific soil map units is available in the USDA-NRCS county soil surveys.

Table 11. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 0-1% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 90-98% |

| Forb foliar cover | 1-5% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 0% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-1% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-1% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 0% |

Table 12. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | – | – | 10-30% | 1-5% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | – | – | 20-30% | 1-5% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | – | – | 20-60% | 1-5% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | – | – | 10-15% | 1-10% |

| >1.4 <= 4 | – | – | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | – | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | – | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | – | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Community 2.2

Minimally managed pasture

Figure 16. min managed pasture grazed

Figure 17. Minimally managed pasture-ungrazed but mowed

Sites in this phase were under low-levels of management usually due in part to the steep slopes, high rock content, and shallow soils. Many of the minimally managed pasture sites had encroaching eastern red cedar, locust, multiflora rose, greenbriers, ironweed, and other non-grass species. Sites were typically characterized by slopes of 15 percent or greater, visible surface rock, and soils 12 to 20 inches in depth. These characteristics made the pastures difficult to manage mechanically. Most sites showed signs of overgrazing. Undesirable pasture species, including noxious weeds, were often present and soil erosion was commonly visible. As expected, the overgrazed sites had a lower percent grass cover, and increased percentage in bare ground, and a wider variety and greater number of invasive weed species. Many pasture sites mapped as Fairmount and Cynthiana were investigated for this project and found to actually be complexes of shallow and moderately deep soils. Twenty pasture sites mapped as Cynthiana were visited, but after site-specific testing (depth probing), twelve of these sites were discovered to actually be a mixture of shallow and moderately deep soils, such as a Cynthiana-Faywood complex. Twenty Fairmount pasture sites were also visited. Sixteen of these twenty sites were actually a complex of shallow and moderately deep soils. In-depth species monitoring was conducted on sites testing as shallow (20" soil depth or less). Graminoids included tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus (Schreb.) Dumort., nom. cons.), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.), orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.) timothy (Phleum pratense L.), smooth brome (Bromus inermis Leyss.), quackgrass (Elymus repens (L.) Gould), perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.), reed Canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea L.), foxtail barley (Hordeum jubatum L.), barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) P. Beauv) and yellow foxtail (Setaria pumila). Common velvet grass (Holcus lanatus L.) was present on two sites. Seeded forb/herb species on sites often included red clover (Trifolium pratense L.), white clover (Trifolium repens L.), and alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). The most common tree species on these sites was eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana L.). Other species found in monitored areas included greenbriers (Smilax L.), blackberries (Rubus L.), giant ironweed (Vernonia gigantea (Walter) Trel.), bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare (Savi) Ten.), Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop.), spiny sowthistle (Sonchus asper (L.) Hill.), spiny amaranth (Amaranthus spinosus L.), buttercup spp. (Ranunculus L.), spiny cocklebur (Xanthium spinosum L.), rough cocklebur (Santhium strumarium L.), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), poison hemlock (Conium maculatum L.), common or lanceleaf ragweed (Ambrosia bidentata Michx.), common yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.), American pokeweed (Phytolacca americana L.), goldenrod spp. (Solidago L.), common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale F.H. Wigg.), Canadian horseweed (Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist), curly dock (Rumex crispus L.), Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota L.), jimsonweed (Datura stramonium L.), black medick (Medicago lupulina L.), Canadian horsenettle (Solanum carolinense L.), Amur (bush) honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii (Rupr.) Herder), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.), mulberry (Morus L.), osage orange (Maclura pomifera (Raf.) C.K.), winged sumac (Rhus copallinum L.), common hackberry (Celtis occidentalis L.), black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.), and honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos L.).

Table 13. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 5-20% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 1-2% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 65-85% |

| Forb foliar cover | 5-15% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 0% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-1% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-5% |

| Bedrock | 0-5% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 0% |

Table 14. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 1-1% | 1-1% | 1-30% | 1-1% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 1-1% | 1-1% | 20-50% | 1-1% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 1-2% | 1-1% | 40-70% | 1-15% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 1-50% | 1-2% | 0-5% | 1-5% |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 1-5% | 1-3% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | – | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | – | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | – | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

With a reduction or absence of management, these site will transition naturally to a minimally managed pasture. The vegetative component of the community will shift from a high percentage of grass to a community more native and invasive forbs and herbs. Tree seedlings/ and saplings, along with vines, will also increase in number and diversity. Future management and recommended conservation practices will depend on landowner goals.

Conservation practices

| Fence | |

|---|---|

| Access Control | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Sites under this project are typically not highly productive pastures due to the shallow, rocky soils; however, some of the lower sloping sites investigated were being utilized as pastureland. On these sites, landowners can make improvements to increase production and protect soil resources. Potential management inputs may include controlled grazing, brush removal, development of a grazing management plan, weed control, and installation of fencing and/or water facilities.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Pond | |

| Fence | |

| Access Control | |

| Forage Harvest Management | |

| Forage and Biomass Planting | |

| Livestock Pipeline | |

| Heavy Use Area Protection | |

| Spring Development | |

| Watering Facility | |

| Water Well | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Stream Crossing | |

| Grazing Management Plan - Applied | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

State 3

Honeysuckle Invaded State

This community is characterized by a midstory and understory dominated by Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii (Rupr.) Herder). Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.), another invasive plant, is often on this sites as well. Honeysuckle varieties were introduced to this country in the 1700s and 1800s as ornamentals; however, their growth form, adaptively, hardiness, and aggressiveness has resulted in dense thickets in forested areas and abandoned fields throughout the Bluegrass region. Often this community has a mixed hardwood overstory that includes oaks, which predate the honeysuckle. A dense midstory of shade- tolerant species such as sugar maple, hackberry, elm, and white ash, is usually present. Juvenile oak and hickory trees were scarce on monitored sites due to the shading effect of the honeysuckle. In areas opened up by felled trees due to wind damage, timber harvest, or disturbance, honeysuckle was especially thick completely shading the forest floor. Honeysuckle is by far the dominant species in the midstory and understory of these communities. A limited number of sugar maple, hackberry, and white ash seedling were found within monitored plots, but oak-hickory regeneration was often completely absent.

Community 3.1

Honeysuckle Invaded Woodland

Figure 18. Honeysuckle woodland 1

Figure 19. honeysuckle woodland 2

Figure 20. honeysuckle woodland 3

Chinkapin oak, sugar maple, and elms were the common overstory tree species on these sites. Sugar maple, white ash, and hackberry were dominant tree species in the midstory and understory. Some hillsides included white oak and hickories but these species were usually a minor component. Honeysuckle was the single dominant species in the lower midstory and understory effectively outcompeting and shading-out native understory plants. The density and dominance of bush honeysuckle on these sites is sufficient to greatly reduce, or in severe cases, prohibit oak-hickory reproduction. The native herbaceous layer in woodlands is also negatively impacted. The low percentage of tree and forb cover is the direct result of the high percentage of shrub (honeysuckle) cover. On many monitored sites, oaks and hickories were absent. Forbs and grasses present were generally non-natives such as tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus (Schreb. Dumort.), garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata (M. Bieb.) Cavara & Grande), Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum (Trin.) A. Camus.), and wintercreeper (Euonymus fortunei (Turcz.)Hand.-Maz). Shade-tolerant tree species such as sugar maple, white ash and hackberry were regenerating in monitored plots but limited in number.

Forest overstory. Overstory composition for these sites consists of oaks and elms that pre-date the honeysuckle invasion along with sugar maple, hackberry, white ash and in few cases, hickory species.

Forest understory. Understory composition consists of honeysuckle species (Amur and Japanese honeysuckle). Oak and hickory regeneration is minimal to non-existent on these sites. Sugar maple regeneration is occuring but minimal. There is no typical forest community herbaceous layer due to the dense mid-story shading from the honeysuckle.

Table 15. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 1-2% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 3-4% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 0-1% |

| Forb foliar cover | 0-1% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0-1% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 25-50% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 1-2% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 1-3% |

| Bedrock | 0-3% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 20-30% |

Table 16. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 0-1% | 1-3% | 0-1% | 0-1% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 0-1% | 1-5% | 0-1% | 0-1% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 0-1% | 2-4% | – | 0-1% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 0-1% | 10-15% | – | – |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 1-2% | 35-65% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | 1-5% | 1-20% | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | 55-75% | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | 0-10% | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

State 4

Transitional Field

This state is the result of pastureland being abandoned and eastern red cedar encroaching into the field. Black locust, honey locust, elms, oaks, and hackberry seedling and saplings were common depending on nearby seed sources. A variety of pasture grasses, weeds, and native forbs were found on these sites. Typically, this state is the natural transition between a managed pasture and an eastern red cedar woodland. Not yet woodland, but no longer a pasture, this successional state is characterized by diversity in plant height, density, and vegetation type (trees, shrubs, grasses, forbs, vines, etc.) thereby providing good wildlife habitat for many native species. These sites were often found on wildlife management areas in Kentucky that were previously a working farm but are now being allowed to naturally transition to a cedar woodland.

Community 4.1

Transitional Shallow Limestone Field

Figure 21. transitional field

This phase is the natural transition of a pastureland moving toward phase 1.3. Planted grasses, typically tall fescue (or a mix of planted grasses), still occupies a significant component of the plant community. Other grass species such as timothy, ryegrass, orchardgrass, Kentucky bluegrass, Johnsongrass, and bromegrass were often present. Eastern red cedar, black locust, honey locust, hackberry, elm, and oak seedling are usually present. Oak, hickory and walnut trees were on site if a nearby seed sources were available. Briars, berries, thistles, ironweed, and an array of herbs were typical for these sites. This community phase is beneficial to many game species and was often found on wildlife management areas and on private property of landowners interested in hunting or wildlife viewing. This phase is characterized by planted pasture grasses, an array of forbs and vines (both native and introduced), seedling hardwood trees, and young eastern red cedars. Eastern red cedar will eventually dominate moving this community to phase 1.3.

Table 17. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 5-10% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 1% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 60-80% |

| Forb foliar cover | 10-30% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 0% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-1% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-1% |

| Bedrock | 0-1% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 0% |

Table 18. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 0-1% | 1-1% | 1-5% | 1-1% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 1-1% | 1-1% | 5-15% | 1-2% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 1-1% | 1-1% | 20-65% | 1-10% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 1-1% | 1-1% | 25-60% | 1-15% |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 1-50% | – | – | 1-10% |

| >4 <= 12 | 0-80% | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | – | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | – | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Substantial management inputs including tree removal and seeding of pasture grasses would move state 1 to state 2. This would be feasible on few sites included under this ESD, due to the steep slopes, surface rock, droughty shallow soils, potential for soil erosion and limited production rates.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The introduction of Amur or bush honeysuckle into oak-hickory woodlands has the potential to completely alter the future community of these sites. Once established, the density and dominance of honeysuckle is sufficient to prohibit oak and hickory regeneration and can entirely replace the native understory community. Introduced from Asia, these species are shade tolerant and form dense thickets in open woods and along forest edges. Honeysuckle plants are fast growing with seeds that germinate quickly in high percentages and are easily transmitted by wildlife and human activity such as road building, recreational uses, livestock grazing, and ground disturbance. Honeysuckle can aggressively spread via root sprouting and compared to many native plants, has longer flowering and seed production periods (Rathfon and Lowe, 2012). Once established, control of honeysuckle requires repeated treatments over multiple years. The seed bank under mature shrubs will remain viable for 2 to 6 years, requiring long-term control efforts. This species is severely impacting the natural composition of woodlands throughout central Kentucky.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The introduction of Amur or bush honeysuckle into oak-hickory woodlands has the potential to completely alter the future community of these sites. Once established the density and dominance of honeysuckle is sufficient to prohibit oak and hickory regeneration and can entirely replace the native understory community. Introduced from Asia, these species are shade tolerant and form dense thickets in open woods and along forest edges. Honeysuckle plants are fast growing with seeds that germinate quickly in high percentages and are easily transmitted by wildlife and human activity such as road building, recreational uses, livestock grazing, and ground disturbance. Honeysuckle can aggressively spread via root sprouting and compared to many native plants, has longer flowering and seed production periods (Rathfon and Lowe, 2012). Once established, control of honeysuckle requires repeated treatments over multiple years. The seed bank under mature shrubs will remain viable for 2 to 6 years, requiring long-term control efforts. This species is fundamentally changing the composition of woodlands throughout central Kentucky.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 4

This is a natural transition from a pasture site to a transitional field. The planted pasture is being encroached upon by eastern red cedar, locusts, briars, other grasses, native forbs, and weeds.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 1

The management inputs necessary to control bush honeysuckle are long-term and intensive. Control measures may include a variety of herbicide treatments (basal bark spray, foliar spray, stump injections, etc.), manual cutting or pulling of plants, mechanical brush removal, fire management, and biological controls. Hand pulling of seedlings is time consuming and tedious, but should be conducted when soils are moist as all of the root must be removed or re-sprouting will occur. Digging or grubbing out larger plants must be done with care, as bare, open soil will result in rapid re-invasion or re-sprouting. Extensive research has been conducted on the use of herbicides to control bush honeysuckle. Applying herbicide to cut stumps is one common treatment method for larger plants. Cutting should be avoided during the winter as it “prunes” the plants and encourages more vigorous resprouting. Research at Purdue University has shown that the herbicides Picloram and 2,4-D or 20 percent triclopyr ester in an oil carrier are highly effective for this method but follow-up treatments will be required. (Rathfon and Lowe, 2012). Landowners can obtain free technical information and assistance from their local NRCS office or university extension service in the selection and use of herbicides. Spring prescribed burning has been shown to kill bush honeysuckle seedlings and damage the tops of mature plants; however, these plants will easily re-sprout so it may be necessary to burn annually or biennially for five years or more for effective control. (Missouri Department of Conservation, 2011)

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Fence | |

| Access Control | |

| Tree/Shrub Site Preparation | |

| Tree/Shrub Establishment | |

| Upland Wildlife Habitat Management | |

| Forest Stand Improvement | |

| Forest Management Plan - Applied | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

Restoration pathway R3B

State 3 to 2

Low quality woodlands with dense honeysuckle could be transitioned to a pasture state on lower-slope sites. The cost and level of inputs for this restoration would depend on access, age of trees, density of honeysuckle and goals of the landowner. This restoration would be a long-term effort requiring planting of desired species and multiple years of brush and weed control.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Pond | |

| Fence | |

| Access Control | |

| Forage and Biomass Planting | |

| Livestock Pipeline | |

| Spring Development | |

| Watering Facility | |

| Water Well | |

| Forest Stand Improvement | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Stream Crossing | |

| Grazing Management Plan - Applied | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 1

A transitional field will move naturally with time to an eastern red cedar woodland. However, depending on the length of time in pasture and the available seed sources naturally available, restoration activities may be required. Most long-term pasture sites will not have the oak-hickory seed source necessary to transition successfully to a mature oak-hickory forest. Tree planting, timber stand improvement activities (removal of less desirable tree species), weed and grass control, and planting of native understory species may be required to fully restore this community.

Conservation practices

| Fence | |

|---|---|

| Access Control | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Forest Management Plan - Applied |

Restoration pathway R4B

State 4 to 2

With management inputs, the transitional field state could be restored back to a pasture state. Tree removal, mowing, weed control, seeding, and fertilizing may be required. Because this ecological site description includes rocky sites with soil depths of 10 to 20 inches, landowners should be advised to consider their site characteristics carefully. Many of these transitional field sites were previously pasture and were abandoned becuase of low productivity and difficulty in management due to slope and rock content. Control of cedar, if so desired, can be accomplished by burning, chemical control, or manual removal. Eastern red cedar seedlings and saplings are very susceptible to fire with winter or spring burning usually recommended as the leaf water content is lower. However, research has shown burning is most effective on cedars up to 1m tall (3.3 feet) although larger trees can be occasionally killed (Anderson, 2003). Burning is not without complications including incomplete control, narrow window of conditions, need for grazing management (pre and post burn), and risk of fire escape.

Conservation practices

| Conservation Cover | |

|---|---|

| Critical Area Planting | |

| Fence | |

| Access Control | |

| Forage and Biomass Planting | |

| Livestock Pipeline | |

| Watering Facility | |

| Water Well | |

| Grazing Management Plan - Applied | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

Additional community tables

Table 19. Community 1.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 7.6–25.9 | 15–50 | 40.6–47 | – |

| chinquapin oak | QUMU | Quercus muehlenbergii | Native | 9.1–25.9 | 20–40 | 45.7–55.9 | – |

| Shumard's oak | QUSH | Quercus shumardii | Native | 8.2–27.4 | 15–40 | 45.7–53.3 | – |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 9.1–27.4 | 15–30 | 43.2–48.3 | – |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | 7.6–22.9 | 0–25 | 40.6–45.7 | – |

Table 20. Community 1.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| hairy woodland brome | BRPU6 | Bromus pubescens | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 1–3 | |

| Bosc's panicgrass | DIBO2 | Dichanthelium boscii | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–2 | |

| eastern bottlebrush grass | ELHY | Elymus hystrix | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| celandine poppy | STDI3 | Stylophorum diphyllum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 5–30 | |

| dwarf larkspur | DETR | Delphinium tricorne | Native | 0–0.2 | 5–25 | |

| cutleaf toothwort | CACO26 | Cardamine concatenata | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–20 | |

| mayapple | POPE | Podophyllum peltatum | Native | 0.2–0.3 | 1–20 | |

| white snakeroot | AGALA | Ageratina altissima var. altissima | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 10–20 | |

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | Native | 0–0.3 | 5–15 | |

| blisterwort | RARE2 | Ranunculus recurvatus | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–15 | |

| harbinger of spring | ERBU | Erigenia bulbosa | Native | – | 5–15 | |

| yellow fumewort | COFL3 | Corydalis flavula | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 1–10 | |

| wild comfrey | CYVI | Cynoglossum virginianum | Native | 0–0.5 | 2–10 | |

| Virginia springbeauty | CLVI3 | Claytonia virginica | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–10 | |

| Canadian blacksnakeroot | SACA15 | Sanicula canadensis | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–10 | |

| bellwort | UVULA | Uvularia | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–10 | |

| early meadow-rue | THDI | Thalictrum dioicum | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–10 | |

| rue anemone | THTH2 | Thalictrum thalictroides | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–10 | |

| toadshade | TRSE2 | Trillium sessile | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–5 | |

| goldenseal | HYCA | Hydrastis canadensis | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–5 | |

| clustered blacksnakeroot | SAOD | Sanicula odorata | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–5 | |

| soft agrimony | AGPU | Agrimonia pubescens | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–5 | |

| pointedleaf ticktrefoil | DEGL5 | Desmodium glutinosum | Native | 0–0.3 | 1–5 | |

| eastern false rue anemone | ENBI | Enemion biternatum | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–5 | |

| spring blue eyed Mary | COVE2 | Collinsia verna | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–5 | |

| wild blue phlox | PHDI5 | Phlox divaricata | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–5 | |

| Virginia snakeroot | ARSE3 | Aristolochia serpentaria | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–3 | |

| crossvine | BICA | Bignonia capreolata | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–3 | |

| dutchman's breeches | DICU | Dicentra cucullaria | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–2 | |

| beaked agrimony | AGRO3 | Agrimonia rostellata | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–2 | |

| hairy alumroot | HEVI2 | Heuchera villosa | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–2 | |

| feathery false lily of the valley | MARA7 | Maianthemum racemosum | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–2 | |

| downy pagoda-plant | BLCI | Blephilia ciliata | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 1–2 | |

| smallspike false nettle | BOCY | Boehmeria cylindrica | Native | 0.2–0.5 | 1–2 | |

| spring avens | GEVE | Geum vernum | Native | 0–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| white avens | GECA7 | Geum canadense | Native | 0–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| woodland sunflower | HEDI2 | Helianthus divaricatus | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| sharplobe hepatica | HENOA | Hepatica nobilis var. acuta | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| roundlobe hepatica | HENOO | Hepatica nobilis var. obtusa | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| hairy alumroot | HEVI2 | Heuchera villosa | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| panicledleaf ticktrefoil | DEPA6 | Desmodium paniculatum | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 1 | |

| fourleaf yam | DIQU | Dioscorea quaternata | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| Virginia strawberry | FRVI | Fragaria virginiana | Native | 0–0.1 | 1 | |

| cream avens | GEVI4 | Geum virginianum | Native | 0–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| crinkleroot | CADI10 | Cardamine diphylla | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1 | |

| Clayton's sweetroot | OSCL | Osmorhiza claytonii | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| spring forget-me-not | MYVE | Myosotis verna | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| roundleaf ragwort | PAOB6 | Packera obovata | Native | 0–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| limestone wild petunia | RUST2 | Ruellia strepens | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| smooth rockcress | ARLA | Arabis laevigata | Native | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

| early saxifrage | SAVI5 | Saxifraga virginiensis | Native | 0–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| woodland stonecrop | SETE3 | Sedum ternatum | Native | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

| Greek valerian | PORE2 | Polemonium reptans | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| smooth Solomon's seal | POBI2 | Polygonatum biflorum | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| Canadian woodnettle | LACA3 | Laportea canadensis | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| jumpseed | POVI2 | Polygonum virginianum | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| Christmas fern | POAC4 | Polystichum acrostichoides | Native | 0–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| rock buttercup | RAMI2 | Ranunculus micranthus | Native | 0–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| licorice bedstraw | GACI2 | Galium circaezans | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| shining bedstraw | GACO3 | Galium concinnum | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| wavyleaf aster | SYUN | Symphyotrichum undulatum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| Jack in the pulpit | ARTR | Arisaema triphyllum | Native | – | 0–1 | |

| wreath goldenrod | SOCA4 | Solidago caesia | Native | 0.1–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| zigzag goldenrod | SOFL2 | Solidago flexicaulis | Native | 0.1–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| common blue wood aster | SYCO4 | Symphyotrichum cordifolium | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| late purple aster | SYPA11 | Symphyotrichum patens | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| twinleaf | JEDI | Jeffersonia diphylla | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| fire pink | SIVI4 | Silene virginica | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| stickywilly | GAAP2 | Galium aparine | Native | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

| bloodroot | SACA13 | Sanguinaria canadensis | Native | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

| white fawnlily | ERAL9 | Erythronium albidum | Native | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

| limestone bittercress | CADO | Cardamine douglassii | Native | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

|

Fern/fern ally

|

||||||

| ebony spleenwort | ASPL | Asplenium platyneuron | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 1–2 | |

| walking fern | ASRH2 | Asplenium rhizophyllum | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| rattlesnake fern | BOVI | Botrychium virginianum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 1 | |

|

Tree

|

||||||

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 10–15 | |

| chinquapin oak | QUMU | Quercus muehlenbergii | Native | 2.4–4.6 | 0–10 | |

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 2.4–4.6 | 1–10 | |

| white ash | FRAM2 | Fraxinus americana | Native | 2.4–4.6 | 0–5 | |

| Shumard's oak | QUSH | Quercus shumardii | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 0–5 | |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | 0.2–0.5 | 1–5 | |

| white ash | FRAM2 | Fraxinus americana | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 1–5 | |

| blue ash | FRQU | Fraxinus quadrangulata | Native | 0.2–0.3 | 0–3 | |

| chinquapin oak | QUMU | Quercus muehlenbergii | Native | 0.2–0.5 | 1–2 | |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | 1.5–3 | 0–1 | |

| blue ash | FRQU | Fraxinus quadrangulata | Native | 2.4–4.6 | 0–1 | |

| mockernut hickory | CATO6 | Carya tomentosa | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| Ohio buckeye | AEGL | Aesculus glabra | Native | 1.5–2.4 | 0–1 | |

| eastern redbud | CECA4 | Cercis canadensis | Native | 2.4–4.6 | 0–1 | |

| eastern redcedar | JUVI | Juniperus virginiana | Native | 0.2–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| American elm | ULAM | Ulmus americana | Native | 0.2–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| slippery elm | ULRU | Ulmus rubra | Native | 0.2–0.5 | 0–1 | |

|

Vine/Liana

|

||||||

| Virginia creeper | PAQU2 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | Native | 0.2–6.1 | 1–5 | |

| eastern poison ivy | TORA2 | Toxicodendron radicans | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–2 | |

| roundleaf greenbrier | SMRO | Smilax rotundifolia | Native | 0–1.5 | 0–1 | |

| bristly greenbrier | SMTA2 | Smilax tamnoides | Native | 0–1.5 | 0–1 | |

| summer grape | VIAE | Vitis aestivalis | Native | 0.3–3.7 | 0–1 | |

| frost grape | VIVU | Vitis vulpina | Native | 0.2–3 | 0–1 | |

Table 21. Community 1.2 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 4.6–21.9 | 50–80 | 38.1–48.3 | – |

| chinquapin oak | QUMU | Quercus muehlenbergii | Native | 12.2–22.3 | 20–35 | 40.6–43.2 | – |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 12.2–22.9 | 10–30 | 38.1–45.7 | – |

| Shumard's oak | QUSH | Quercus shumardii | Native | 12.2–21.3 | 20–25 | 40.6–45.7 | – |

Table 22. Community 1.2 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–5 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| Virginia springbeauty | CLVI3 | Claytonia virginica | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–15 | |

| white snakeroot | AGALA | Ageratina altissima var. altissima | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 10–15 | |

| Canadian blacksnakeroot | SACA15 | Sanicula canadensis | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–15 | |

| dwarf larkspur | DETR | Delphinium tricorne | Native | 0–0.2 | 5–10 | |

| harbinger of spring | ERBU | Erigenia bulbosa | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| mayapple | POPE | Podophyllum peltatum | Native | – | 1–10 | |

| cutleaf toothwort | CACO26 | Cardamine concatenata | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–7 | |

| clustered blacksnakeroot | SAOD | Sanicula odorata | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–5 | |

| bellwort | UVULA | Uvularia | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–5 | |

| toadshade | TRSE2 | Trillium sessile | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–5 | |

| early meadow-rue | THDI | Thalictrum dioicum | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–5 | |

| yellow fumewort | COFL3 | Corydalis flavula | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 1–5 | |

| soft agrimony | AGPU | Agrimonia pubescens | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 1–5 | |

| goldenseal | HYCA | Hydrastis canadensis | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–5 | |

| blisterwort | RARE2 | Ranunculus recurvatus | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–5 | |

| spring blue eyed Mary | COVE2 | Collinsia verna | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–5 | |

| wild blue phlox | PHDI5 | Phlox divaricata | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–5 | |

| celandine poppy | STDI3 | Stylophorum diphyllum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 1–3 | |

| Virginia snakeroot | ARSE3 | Aristolochia serpentaria | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–3 | |

| crossvine | BICA | Bignonia capreolata | Native | 0–0.1 | 1–3 | |

| pointedleaf ticktrefoil | DEGL5 | Desmodium glutinosum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–3 | |

| feathery false lily of the valley | MARA7 | Maianthemum racemosum | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–2 | |

| spring avens | GEVE | Geum vernum | Native | 0–0.6 | 1–2 | |

| cream avens | GEVI4 | Geum virginianum | Native | 0–0.6 | 0–2 | |

| Canadian woodnettle | LACA3 | Laportea canadensis | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–2 | |

| smallspike false nettle | BOCY | Boehmeria cylindrica | Native | 0.2–0.5 | 1–2 | |

| fourleaf yam | DIQU | Dioscorea quaternata | Native | – | 0–1 | |

| fourleaf yam | DIQU | Dioscorea quaternata | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| roundleaf ragwort | PAOB6 | Packera obovata | Native | 0–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| Clayton's sweetroot | OSCL | Osmorhiza claytonii | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| white avens | GECA7 | Geum canadense | Native | 0–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| panicledleaf ticktrefoil | DEPA6 | Desmodium paniculatum | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| stickywilly | GAAP2 | Galium aparine | – | 0.2–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| stickywilly | GAAP2 | Galium aparine | Native | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

| white fawnlily | ERAL9 | Erythronium albidum | Native | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

| bloodroot | SACA13 | Sanguinaria canadensis | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| hairy alumroot | HEVI2 | Heuchera villosa | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| Jack in the pulpit | ARTR | Arisaema triphyllum | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| downy pagoda-plant | BLCI | Blephilia ciliata | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| wild comfrey | CYVI | Cynoglossum virginianum | Native | 0–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| sharplobe hepatica | HENOA | Hepatica nobilis var. acuta | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| roundlobe hepatica | HENOO | Hepatica nobilis var. obtusa | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| beaked agrimony | AGRO3 | Agrimonia rostellata | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| smooth Solomon's seal | POBI2 | Polygonatum biflorum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| jumpseed | POVI2 | Polygonum virginianum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| crinkleroot | CADI10 | Cardamine diphylla | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| spring forget-me-not | MYVE | Myosotis verna | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| licorice bedstraw | GACI2 | Galium circaezans | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| shining bedstraw | GACO3 | Galium concinnum | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| hairy alumroot | HEVI2 | Heuchera villosa | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| Greek valerian | PORE2 | Polemonium reptans | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| squirrel corn | DICA | Dicentra canadensis | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| eastern false rue anemone | ENBI | Enemion biternatum | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| rue anemone | THTH2 | Thalictrum thalictroides | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

|

Fern/fern ally

|

||||||

| ebony spleenwort | ASPL | Asplenium platyneuron | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 1 | |

| walking fern | ASRH2 | Asplenium rhizophyllum | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| bladderfern | CYSTO | Cystopteris | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| Christmas fern | POAC4 | Polystichum acrostichoides | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

|

Tree

|

||||||

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 2–10 | |

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 0.9–3 | 1–5 | |

| Shumard's oak | QUSH | Quercus shumardii | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 0.9–1.8 | 0–1 | |

| elm | ULMUS | Ulmus | Native | 0.2–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| elm | ULMUS | Ulmus | Native | 0.9–1.5 | 0–1 | |

| white ash | FRAM2 | Fraxinus americana | Native | 0.3–0.9 | 0–1 | |

| white ash | FRAM2 | Fraxinus americana | Native | 2.1–3.7 | 0–1 | |

| blue ash | FRQU | Fraxinus quadrangulata | Native | 0.6–1.2 | 0–1 | |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | 0.3–0.8 | 0–1 | |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | 1.2–2.1 | 0–1 | |

| mockernut hickory | CATO6 | Carya tomentosa | Native | 1.5–2.7 | 0–1 | |

| eastern redcedar | JUVI | Juniperus virginiana | Native | 0.2–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| eastern redbud | CECA4 | Cercis canadensis | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| eastern redbud | CECA4 | Cercis canadensis | Native | 1.5–3.7 | 0–1 | |

| Shumard's oak | QUSH | Quercus shumardii | Native | 2.1–3.7 | 0–1 | |

|

Vine/Liana

|

||||||

| Virginia creeper | PAQU2 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | Native | 0.2–3 | 1 | |

| frost grape | VIVU | Vitis vulpina | Native | 0.2–1.5 | 0–1 | |

| roundleaf greenbrier | SMRO | Smilax rotundifolia | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| bristly greenbrier | SMTA2 | Smilax tamnoides | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| eastern poison ivy | TORA2 | Toxicodendron radicans | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| summer grape | VIAE | Vitis aestivalis | Native | 0.2–3 | 0–1 | |

Table 23. Community 1.3 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| eastern redcedar | JUVI | Juniperus virginiana | Native | 1.5–10.7 | 80–90 | 5.1–30.5 | – |

Table 24. Community 1.3 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| tall fescue | SCAR7 | Schedonorus arundinaceus | Introduced | 0–0.3 | 20–40 | |

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–5 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| lespedeza | LESPE | Lespedeza | Introduced | 0.1–0.4 | 0–5 | |

| Canadian blacksnakeroot | SACA15 | Sanicula canadensis | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–2 | |

| eastern poison ivy | TORA2 | Toxicodendron radicans | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–2 | |

| Virginia creeper | PAQU2 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–2 | |

| white snakeroot | AGALA | Ageratina altissima var. altissima | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 1–2 | |

| ebony spleenwort | ASPL | Asplenium platyneuron | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

|

Fern/fern ally

|

||||||

| ebony spleenwort | ASPL | Asplenium platyneuron | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| multiflora rose | ROMU | Rosa multiflora | Introduced | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

|

Tree

|

||||||

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 0.3–0.6 | 1–10 | |

| eastern redbud | CECA4 | Cercis canadensis | Native | 1.5–3 | 1–5 | |

| chinquapin oak | QUMU | Quercus muehlenbergii | Native | 0.3–0.9 | 1–2 | |

| white ash | FRAM2 | Fraxinus americana | Native | 0.2–0.3 | 1–2 | |

| black locust | ROPS | Robinia pseudoacacia | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| honeylocust | GLTR | Gleditsia triacanthos | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| eastern redbud | CECA4 | Cercis canadensis | Native | 0.2–0.3 | 1 | |

| blue ash | FRQU | Fraxinus quadrangulata | Native | 0.3–0.6 | 0–1 | |

|

Vine/Liana

|

||||||

| frost grape | VIVU | Vitis vulpina | Introduced | 0.2–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| bristly greenbrier | SMTA2 | Smilax tamnoides | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

Table 25. Community 3.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| common hackberry | CEOC | Celtis occidentalis | Native | 6.7–20.7 | 0–50 | 22.9–43.2 | – |

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 9.1–24.4 | 20–50 | 43.2–50.8 | – |

| chinquapin oak | QUMU | Quercus muehlenbergii | Native | 10.7–25.9 | 20–45 | 45.7–53.3 | – |