Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F121XY003KY

Weathered Shale Upland

Last updated: 10/01/2024

Accessed: 04/18/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

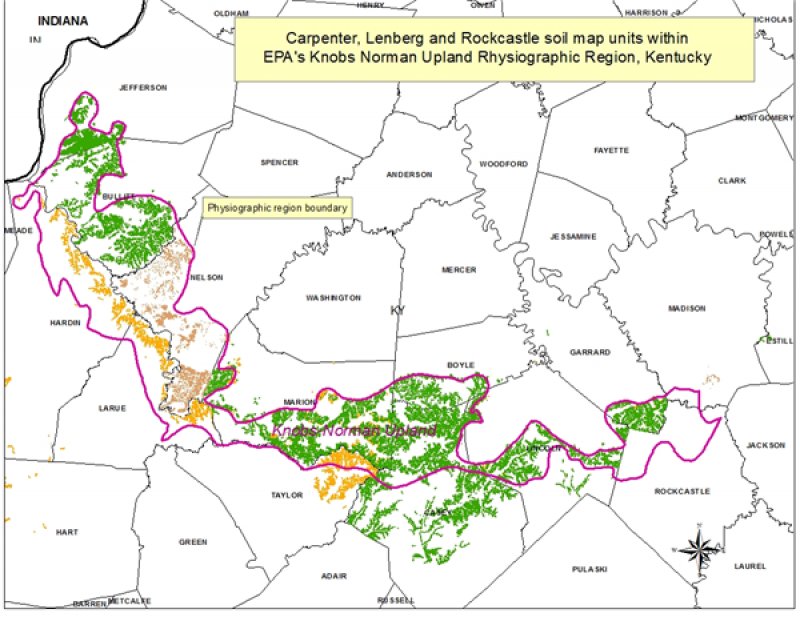

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 121X–Kentucky Bluegrass

USDA-NRCS’s MLRA 121, the Kentucky Bluegrass MLRA, covers portions of central and northern Kentucky, southern Ohio, and Indiana. 83% of the MLRA is located in Kentucky, predominately central and western portions of the state. The MLRA is approximately 10,700 square miles and encompasses multiple major cities including Cincinnati, Ohio, Louisville, Kentucky and Lexington, Kentucky. The majority of the MLRA acreage is in the Lexington Plain Section of the Interior Low Plateaus Province of the Interior Plains. A portion of southern Ohio and southern Indiana are generally part of the Till Plains Section of the Central Lowland Province of the Interior Plains.

Typically, the landscape of the MLRA is rolling hills, pastureland for livestock and/or horses, and increasingly subdivisions and/or urban development. Dominant soils include Alfisols, Inceptisols, and Mollisols which range from shallow to very deep. Generally, the soils are have a mesic temperature regime, an udic soil moisture regime and mixed mineralogy.

The natural vegetation of this area is a mixed deciduous forest with a variety of oak and hickory species including white oak, black oak, Shumard oak, chinkapin oak, northern red oak bur oak, pignut hickory, shagbark hickory, bitternut hickory and mockernut hickory. Other common species include sugar maple, white ash, blue ash, black locust, hackberry, Kentucky coffee tree, American elm, black cherry and black walnut. Less than 1/3 of this area is still forested and the large majority of those acres have been repeatedly harvested. Pastureland, cropland and urban development account for about 70% of the MLRA. With the exception of the central Kentucky thoroughbred farms, the majority of rural land ownership is small to medium size farms that produce cattle, hay, corn, and tobacco. Due to the low quality of the woodlands, forest products are generally not commercially important in the region.

Classification relationships

This ecological site is related to the Southern Interior Low Plateau Dry-Mesic Oak Forest(CES202.898), Primary Division: Central Interior and Appalachian (202), Land Cover Class: Forest and Woodland.

The Association for Biodiversity Information (ABI) has published a document entitled "Plant Communities of the Midwest-Classification in an Ecological Text" which contains communities with similarities to states and phases includded in this ecological site description. There are conceptual relationship to the following communities:

A.) Quercus prinus- Quercus (Q. alba, Q. coccinea, Q. velutina) / Virbunum acerifolium Forest (Appalachian /Interior Low Plateau Oak Forest, CEGL005023).

B.) Quercus prinus / Smilax spp. Forest (CEGL005022).

The Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission has identified 15 Forest Communities in Kentucky. This ecological site closely relates to KSNPCs Acidic sub-xeric forest- Conservation status: S5. KNSPC describes these communities as occupying middle and upper slopes of hills and ridges and other relatively dry upland areas over acidic rock types. Aspects are variable but this community type is best developed usually on south and west slopes. Soils are well drained and moderately deep. Parent materials include acidic substrates such as shale, siltstone and sandstone. The tree canopy is mostly closed. The forests are mainly oak and oak-hickory dominated. The understory communities are poorly developed and the ground cover somewhat sparse. Dominant and characteristic trees include Quercus alba, Q. prinus, Q. velutina, Q. falcata, Q. coccinea, Carya glabra, C. ovalis, and C.tomentosa. (syn= dry acid forest, oak-hickory forest, oak forest).

Applicable USFS ecoregions:

Domain: # 200- Humid Temperate; Division: Hot Continental; Province: #222 -Eastern Broadleaf Forest (Continental) Province; Sections: #222F - Interior Low Plateau.

Ecological site concept

The Weathered Shale Upland ecological site description was developed within the Knobs-Norman Upland Ecoregion of central Kentucky. The ecological sites are found on sideslopes throughout the western Knobs region on soils formed over weathered gray shale. Sites are characterized by an intertwining mosaic of deep and moderately deep soils. Representative soils include: Carpenter, Lenberg, Rockcastle.

Vegetation is influenced by gradients of soil depth, aspect, and topography. Soil depths of sites evaluated for this project were between 35 and 52 inches. These soils provide adequate moisture for many species of hardwood trees including white oak (Quercus alba), chestnut oak (Q. prinus), black oak (Q. velutina), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), shagbark hickory (C. ovata), and on deeper, protected sites, northern red oak (Q. rubra). Soil map units included in this project are predominately forested due to slopes. Representative soils include: Carpenter, Lenberg, Rockcastle.

Because of layered geology, differences in soils occurred rapidly up and down the hillsides. Therefore, soil and vegetation characteristics on these sites are not always identical. The state and transition model (STM) is limited to two plant species at each level (tree, shrub, and herbaceous layers) and therefore, does not reflect the natural variation of these sites. The STM describes the most common site characteristic found during one year of field work.

Understory communities are influenced by differences in soil depths, site aspect, micro-topography, rock content, and soil parent material. A well-developed herbaceous layer was indicative of deeper soils and a more protected environments such as north and east slopes. Tree species also varied by aspect. Red oak was found on protected slopes, while pignut hickory and chestnut oak were more frequent on south and west slopes.

Associated sites

| F121XY003KY |

Weathered Shale Upland Weathered Shale Uplands |

|---|---|

| F121XY008KY |

Moderately Deep Shale-Siltstone Backslope Moderately Deep Shale Siltstone Backslope |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Quercus alba |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Vaccinium pallidum |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Smilax rotundifolia |

Physiographic features

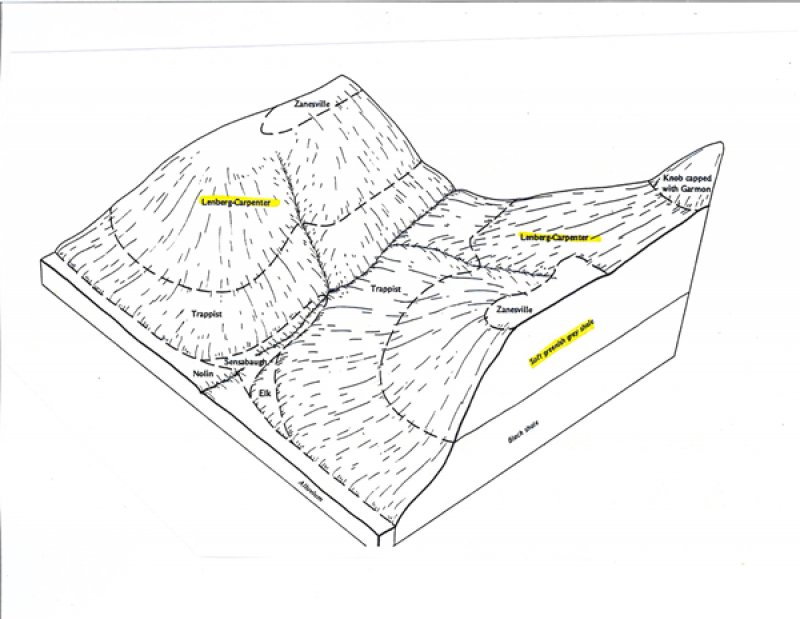

These ecological sites are found on hillsides in the Knobs Norman Upland Physiographic region on Kentucky. Soils range in depth from moderately deep to deep and are predominately formed in residuum or residuum and colluvium of gray shale and siltstone. There is no water table, flooding or ponding on these sites due to slope. The runoff class is variable ranging from very low to high.

Figure 2. Capenter Lenberg Rockcastle Soils in Kentuckys Kno

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hill

(2) Ridge (3) Knob |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Low to very high |

| Elevation | 168 – 416 m |

| Slope | 2 – 50% |

| Water table depth | 183 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

These ecological sites are located in MLRA 121 and are at the northern periphery of the humid subtropical climate zone. Generally characterized by hot, humid summers and cold winter, the area has four distinct seasons. The expected annual precipitation for sites included in this ecological site description is generally in the range of 40 to 50 inches. The majority of precipitations falls during the freeze-free months, and thunderstorms with heavy rainfall are common during the spring and summer months. The freeze-free period varies somewhat based on localized topography and longitude.

The average annual precipitation in most of this area is 41 to 45 inches. It is 45 to 52 inches along the southern edge of the area. About one-half of the precipitation falls during the growing season. Most of the rainfall occurs as high-intensity, convective thunderstorms. The annual snowfall averages about 14 inches (370 millimeters). The average annual temperature is 51 to 57 degrees F (10 to 14 degrees C).

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 157 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 184 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 1,270 mm |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 157 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 184 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 1,270 mm |

| Frost-free period (average) | 157 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 184 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 1,270 mm |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 6. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 7. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 8. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BARDSTOWN 5E [USC00150397], Bardstown, KY

Influencing water features

No water features exist on theses sites.

Soil features

Some of the best examples of this ecological site were found in Bullitt, Jefferson, Nelson, Marion, and Casey counties of Kentucky. The landscape in the Knobs Norman Upland region is conical hills connected by long, narrow ridges and steep to very steep hillsides and ridgetops. The ridges and knobs are dissected by small, intermittent streams which contain small riparian ecosystems that differ from the oak-hickory woodlands described in this ecological site description which are found on the steep backslopes and ridges. During this study, the soil mapunits which best reflected these ecological sites included Lenberg-Carpenter complex, 20-40 percent slope (Soil Survey of Bullitt and Spencer Counties, Kentucky); Carpenter-Lenberg complex, 12-30 percent slope (Soil Survey of Garrard and Lincoln Counties, Kentucky); Carpenter-Lenberg complex, 20-40 percent slope, eroded (Soil Survey of Marion County, Kentucky); Lenberg-Carpenter complex, 12-30 percent slope (Soil Survey of Casey County, Kentucky).

Figure 9. Landscape position, Carpenter Lenberg Complex, Bul

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

clayey shale

(2) Colluvium – acid shale |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Gravelly sandy loam (2) Flaggy silty clay loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Slow to very slow |

| Soil depth | 61 – 152 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

10.16 – 15.24 cm |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

4 – 7.3 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

7 – 20% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 12% |

Ecological dynamics

This PES encompasses an oak-hickory forest community on soils underlain by predominately weathered shale. The range of variation in plant composition on these sites vary mainly due to soil depth, available water, and aspect.

Actual field work is required to develop a full ecological site description (ESD), a field-based state and transition model, and accurate plant community phases to support future conservation planning.

State 1. (Reference):

State 1, Phase 1.1: Plant species dominants:

Quercus alba-Quercus prinus/Vaccinium spp. /Smilax rotundifolia-Carex spp.

(white oak – chestnut oak / blueberry / greenbrier – sedges)

Plant communities on these sites are influenced by variations in soil depth, rock content, slope, pH, aspect, micro-topography, and available water. Sites are on sloping hillsides and ridges mostly within the Knobs Norman Upland Physiographic Region. Generally, north slopes and sites with deeper soils have a reference community of mixed oaks or oak-hickory components. Dominant tree species include chestnut oak (Quercus prinus), white oak (Quercus alba), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), Carya ovata (shagbark hickory), black oak (Quercus velutina), and scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea). Additional species found on these sites may include blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), winged elm (Ulmus alata), persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), red maple (Acer rubrum), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), mockernut (Carya tomentosa), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), redbud (Cercis canadensis), and blackhaw (Viburnum prunifolium). South-facing slopes and sites with shallow soils have plant communities that reflect the resulting reduction in available water. These communities likely include Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana). The floristic expression of these sites varies with the individual site characteristics that influence available water.

Shrubs and woody vines on these sites may include:

Lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum)

Deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum)

Black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata)

Greenbriers (Smilax rotundifolia or round-leaf greenbrier most commonly)

Poison ivy (Rhus radicans)

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Grape (Vitis spp.)

Typical herbs may include:

Poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

Bedstraw (Galium spp.)

Panicgrass (Panicum spp.)

Hawkweed (Hieraceum venosum)

False dandelion (Krigia biflora)

Sedges (Carex digitalis, Carex umbellate, Carex wildenovii and others)

Spiderwort (Tradescantia virginiana)

State: 2. Pasture

State 2, Phase 2.1: Managed Pasture.

Plant species dominants: Schedonorus arundinaceus (tall fescue)

State 2, Phase 2.2: Minimally Managed Pasture.

Plant species dominants: Schedonorus arundinaceus - Andropogon virginicus (tall fescue – broom

A pasture phase for this provisional ecological community is feasible only on lower sloping sites. Many sloping shale sites are too steep for this state and should only be managed as woodlands. Plant species within pasture phases depend on seeding, management, and concurrent land uses. As with all sites, soil characteristics and management inputs will influence production levels.

Transitioning this state to a reference condition would likely require extensive and long-term timber stand improvement practices including control of non-native vegetation and management for desired oak or hickory species.

State: 3. Transitional Field

State 3, Phase 3.1: Plant species dominants:

Acer spp. / Rhus spp. - Rubus spp. /Schedonorus arundinaceus –Andropogon virginicus

(maples / sumac –blackberry / tall fescue – broomsedge)

After a field is abandoned, it is first occupied by a ruderal plant community until shrubs and trees become established. Common old field species within the Knobs include:

Common yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

Spiny amaranth (Amaranthus spinosus L.)

Broomsedge or broomsedge bluestem (Andropogon virginicus)

Indianhemp or hemp dogbane (Apocynum cannabinum L.)

Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.)

Eastern daisy fleabane (Erigeron annuus)

Rumpet creeper (Campsis radicans (L.) Seem. Ex Bureau)

Field thistle (Cirsium discolor (Muhl. ex Willd.) Spreng.)

Canadian horse weed (Erigeron Canadensis, SYN= Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist var. canadensis)

Cudweed or spoonleaf purple everlasting, (Gnaphalium purpureum, SYN= Gamochaeta purpurea (L.) Cabrera)

American false pennyroyal, (Hedeoma pulegioides)

Spotted St. Johnswort (Hypericum punctatum)

Canada lettuce (Lactuca Canadensis)

Lespedeza spp. Both native and non-native species may be present including hairy lespedeza (Lespedeza hirta (L.) Hornem. and sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneate)

Purple passionflower (Passiflora incarnata L.)

Common cinquefoil (Potentilla simplex)

Buttercups (Ranunculus spp.)

Winged sumac (Rhus copallina)

Blackberry (Rubus spp.). Species may include: Rubus occidentalis L., Rubus allegheniensis Porter, Rubus alumnus L.H. Bailey, Rubus flagellaris Willd., etc.

Common yellow woodsorrel, (Oxalis stricta)

Greenbrier species including saw greenbrier (Smilax bona-nox L.), cat greenbrier (Smilax glauca), and the brisley greenbrier (Smilax tamnoides).

Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense L.)

Clasping Venus looking-glass (Triodanis perfoliata (L.) Nieuwl., SYN=Specularia perfoliata)

Hairy white oldfield aster (Symphyotrichum pilosum (Willd.) G.L. Nesom var. pilosum)

Giant ironweed (Vernonia gigantea (Walter) Trel.)

Cocklebur (Xanthium L.)

Non-native vegetation may include:

Annual ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.)

Chicory (Cichorium intybus L.)

Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Canadian thistle (Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop.)

Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota L.)

Multi-flora rose (Rosa multiflora Thunb.)

Curly dock (Rumex crispus)

Common Mullein (Verbascum thapsus L.)

Seedlings and saplings of Quercus spp., Carya spp., Acer spp, (especially red maple, sugar maple, and boxelder) Pinus spp. (commonly Virginia pine), Sassafras albidum, Robinia pseudoacacia (black locust), and Celtis occidentalis (hackberry) would be common.

Transitioning this state to a reference condition will require timber stand improvement practices to control non-native vegetation and manage for higher quality oak or hickory species.

State: 4 – Disturbed Site

State 3, Phases 3.1: Post Large-Scale Disturbance Forest State.

Plant species dominants: Acer spp. – Quercus spp. /Rubus spp. / Smilax spp. – Ageratina altissima (maple – oak / blackberry / greenbrier – white snakeroot).

Tree regeneration on these sites will depend on the severity and duration of disturbance, soil characteristics, adjacent plant communities and seed sources, post-disturbance management inputs, presence or absence of continued site disturbances (grazing, fire, timber cutting), slope, and aspect. Common pioneer species in the Knobs region include: Acer rubrum, Campsis radicans, Diospyros virginiana, Nyssa sylvatica, Pinus virginiana, Quercus prinus, Quercus coccinea, Quercus imbricaria, Rhus copallina, Rubus spp., Sassafras albidum, and Smilax glauca.

Transitioning this state to a reference condition would likely require timber stand improvement practices to control non-native vegetation and manage for desired tree species.

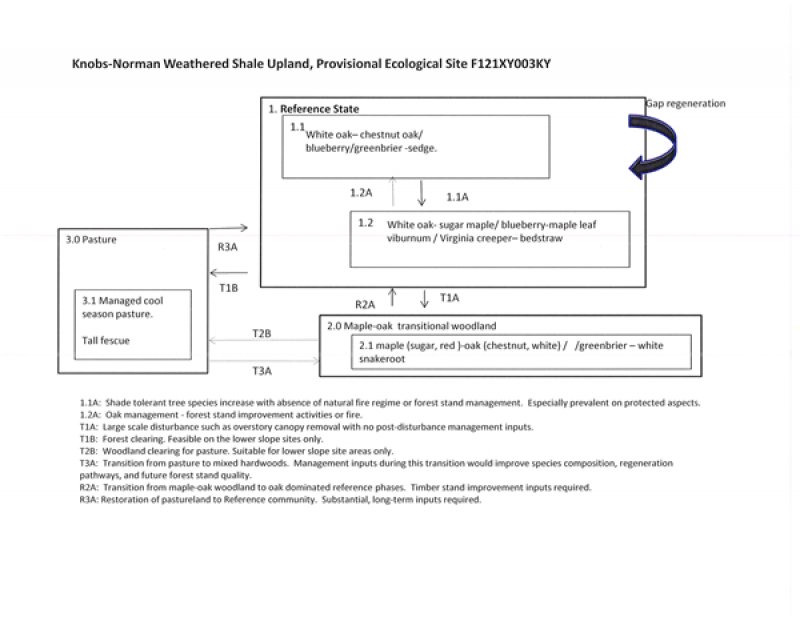

State and transition model

Figure 10. MLRA 121, Group 3

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Knobs Norman Weathered Shale Oak-Hickory Forest

Development of this ecological site description first started with the identification and analyses of existing ecological studies and mapping. One of the key elements utilized in identifying possible work area boundaries for this project was the Ecoregions of Kentucky dataset developed by US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Ecoregions are areas that exhibit similarities in ecosystems including the type of environmental resources. These boundaries where delineated to serve as a spatial framework for environmental research, ecological assessments, natural resource management, and ecosystem monitoring throughout the United States. (Bryce and others, 1999). EPAs ecoregion boundaries were developed through the analysis of environmental spatial patterns including geology, soils, physiography, vegetation, climate, hydrology, and land use. (Wiken, 1986; Omernick, 1987). Two ecoregions make up the distinctive geologic area of Kentucky known as “the Knobs”. Consisting of a relatively narrow band of conical hills surrounding the Outer Bluegrass Ecoregion in a horseshoe shape, the Knobs form a horseshoe shape around the Bluegrass Regions. The vegetation of the Knobs is influenced by geology and soils -and the ecoregions that area adjacent. The eastern portion of the Knobs – referred to as the Knobs-Lower Scioto Dissected Plateau Ecoregion- reflects a combination of plants from both the Outer Bluegrass Region to the west and the Cumberland Plateau ecoregions to the east. The western portion of the Knobs – referred to as the Knobs-Norman Upland- is also influenced by the Outer Bluegrass Ecoregion (to the east) but has characteristics of the Eastern Highland Rim and the Mitchell Plain ecoregions. The noted ecologist Lucy Braun (1950) separated the Knobs area of the Mixed Mesophytic Forest adjacent to the Cumberland Plateau from the Knobs region located in the western and southern parts of the State. EPA has also separated the Knobs into two distinct ecoregions. Although the Knobs region extends into Ohio, no Ohio sites were visited for this project. Previous studies have showed that the vegetation throughout the Ohio Knobs areas can be locally distinctive and vary sharply based upon parent material. (Anderson and Vankat, 1978). For these reasons, this ecological site description is focused on sites and soils within the Knobs-Norman Upland Ecoregion of Kentucky. Many experts describe the Knobs region as exhibiting a blending of mixed mesophytic and Western Mesophytic forest types. Pre-settlement vegetation of the Knobs contained mixed mesophytic forest species such as sugar maple (Acer saccharum), Tilia spp., yellow buckeye [Aesculus octandra (SYN= Aesculus flava Aiton)], and tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera). (Muller and McComb). It also contained elements of the Western Mesophytic forest including forest communities dominated by oaks. (Burroughs 1926; Braun 1950). Past ecological studies have resulted in confirming a strong relationship between soil and site conditions and the distribution of vegetation in the Knobs. It is sometimes difficult to identify vegetation community boundaries in the field or to delineate communities via soil mapping. The sideslopes are a mix of different soils with varying parent materials and soil boundaries are difficult to immediately identify. On hillsides, the substrate changes can happen sharply or on a long gradient depending on the individual site. There have been relatively few previous detailed studies of the vegetation or vegetation and soil relationships in the Knobs region. Wharton (1945) did identified five upland forest types based on her field observation in the region. These were mixed mesophytic forest, white oak, oak-pine, pine, and chestnut oak-scarlet oak. Wharton’s hypothesis was that the distribution of these forest types was based on aspect, slope position, soils/geology, and the successional phase of the community; however, no direct or detailed correlations were identified or field tested in her works. This ecological site description described findings of one year of field work. Public land was utilized for reference sites due to the lower quality of forests found on most private lands. Disturbances, including livestock, clear cutting, and selective harvest had occurred on most of the private lands visited within the last 20 years. The public lands monitored for this project reference site had been protected for over 50 years. The majority of field visits occurred in Bullitt, Jefferson, Marion and Nelson Counties. This ecological site is a dry- mesic oak forest located in the western Knobs region of Kentucky. Depending on slope, soil depth, and soil characteristics, individual trees vary in size with larger specimens generally 70-90 feet in height. Overstory canopy closure on plots was 70-90% and dominant overstory trees included white oak (Quercus alba), chestnut oak (Quercus prinus), black oak (Quercus velutina), scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), and shagbark hickory (Cary ovata). Understory communities were lightly developed, especially on south and western hillsides. Aspect, soil depth, and micro-topography influenced herbaceous cover and species density.

Community 1.1

Weathered Shale Oak-Hickory Forest

Figure 11. 121XY003 Q.alba, Q.prinus 21029-14

Figure 12. 121XY003 Q. alba, Q. prinus 21029-12

Figure 13. 121XY003 Oak-Hickory 21111-19

Figure 14. 121XY003 Q prinus- selective harvest background

Figure 15. 121KY003 Understory example 21111-27

This community phase, located on weathered grayish shale side slopes, is dominated by white oak along with other oak and hickory species. Sites included black oak, red oak, pignut hickory, shagbark hickory, and less commonly scarlet oak. Maple was predominant on north and east aspects. The understory community showed a substantial gradient of variation depending on aspect, slope, soil depth, rock content, micro-topography, and influences of surrounding seed sources. A list of shrubs, herbs and forbs found on monitored sites is listed in the table below.

Forest overstory. White oak, chestnut oak, black oak, shagbark hickory, and pignut hickory were the dominant overstory trees on most monitored sites. The character and diversity of these upland slopes can be described as oak dominated with a hickory component. White oak and chestnut oak were abundant and normally found together on exposed sites. On these drier south facing sites, especially on rocky and shallower soils, chestnut oak prevalent along with pignut hickory. More protected slopes exhibited greater numbers of black oak, shagbark hickory, and northern red oak.

Forest understory. Understory trees on these sites varied depending on soil characteristics, disturbance history, and aspect. Black gum, winged elm, American elm, sassafras, sugar maple, red maple, Virginia pine, sourwood, flowering dogwood, and American beech were all found on monitored slopes.

Shrubs, vines and herbs found on sites varied but often included blueberry, roundleaf greenbrier, Virginia creeper, Gallium spp., mayapples, and sedges.

Table 5. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 1-2% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 1-3% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 1% |

| Forb basal cover | 1-2% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0-1% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 20-45% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 1-3% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 1-2% |

| Bedrock | 0-1% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 0-1% |

Table 6. Woody ground cover

| Downed wood, fine-small (<0.40" diameter; 1-hour fuels) | 1-1% N* |

|---|---|

| Downed wood, fine-medium (0.40-0.99" diameter; 10-hour fuels) | 1-2% |

| Downed wood, fine-large (1.00-2.99" diameter; 100-hour fuels) | 1-2% |

| Downed wood, coarse-small (3.00-8.99" diameter; 1,000-hour fuels) | 0-1% |

| Downed wood, coarse-large (>9.00" diameter; 10,000-hour fuels) | 0% |

| Tree snags** (hard***) | – |

| Tree snags** (soft***) | – |

| Tree snag count** (hard***) | |

| Tree snag count** (hard***) |

* Decomposition Classes: N - no or little integration with the soil surface; I - partial to nearly full integration with the soil surface.

** >10.16cm diameter at 1.3716m above ground and >1.8288m height--if less diameter OR height use applicable down wood type; for pinyon and juniper, use 0.3048m above ground.

*** Hard - tree is dead with most or all of bark intact; Soft - most of bark has sloughed off.

Table 7. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | 1-2% | 1-2% | 1-1% | 1-2% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 1-2% | 0-1% | 1-3% | 10-25% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 1-2% | 5-20% | 1-3% | 5-20% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 1-2% | 5-15% | 0-1% | 0-3% |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 10-45% | 0-1% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | 25-50% | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | 30-70% | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | 40-85% | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Community 1.2

Weathered Shale Oak-Maple Forest

State 2

Knobs Norman Transitional Oak-Maple Woodland

Community 2.1

Transitional Oak-Maple Woodland

Sites evaluated for this phase had been cleared or logged and natural regeneration was occurring with little to no active management inputs. Tree seedling and saplings were a major component of these communities and there were substantial community variations in overstory and understory tree composition depending on the degree of disturbance, restoration attempts, adjacent natural seed sources, soil erosion loss, presence of ongoing disturbances (grazing), fire regime (or lack of), micro-topography, soil characteristics, and aspect. Seedling and saplings ranged from mixed hardwoods (maple, ash, elm) to maple-oak to maple-oak-pine on the sites evaluated. Additional field work, including long-term monitoring plots, are required to accurately predict long-term community development and ecological pathways on these sites. The scope of this ecological site description project was one field season and given that short time frame, it appeared that substantial forest stand improvement inputs would be required to successfully transition this phase to a quality reference site dominated by oak species.

Forest overstory. Typical forest overstory composition on these disturbed sites included sugar maple, red maple, white ash, American beech, elm, and oak. Other species found are listed in the following tables.

Forest understory. Understory regeneration of white oak, chestnut oak, black oak, and in some location, scarlet oak and northern red oak were occurring in the understory; however, these species were being out-competed by faster growing ground vegetation and other tree species. Pignut hickory and shagbark hickory were also recorded in the understory.

Due to the ground disturbance and canopy opening, the density of the understory was much greater than the reference communities.

Introduced non-native plant species were often found along logging roads and vehicle staging areas

Table 8. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 10-50% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 0-1% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 25-60% |

| Forb foliar cover | 5-35% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0-1% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 1-5% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-1% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-1% |

| Bedrock | 0-1% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 1-5% |

Table 9. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 10-60% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 1-2% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 5-35% |

| Forb basal cover | 3-15% |

| Non-vascular plants | 1% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 0-10% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 1-5% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 1-5% |

| Bedrock | 0-5% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 1-5% |

Table 10. Woody ground cover

| Downed wood, fine-small (<0.40" diameter; 1-hour fuels) | 0-1% N* |

|---|---|

| Downed wood, fine-medium (0.40-0.99" diameter; 10-hour fuels) | 0-1% N* |

| Downed wood, fine-large (1.00-2.99" diameter; 100-hour fuels) | 0-1% N* |

| Downed wood, coarse-small (3.00-8.99" diameter; 1,000-hour fuels) | 0% |

| Downed wood, coarse-large (>9.00" diameter; 10,000-hour fuels) | 0% |

| Tree snags** (hard***) | – |

| Tree snags** (soft***) | – |

| Tree snag count** (hard***) | 0 per hectare |

| Tree snag count** (hard***) | 0 per hectare |

* Decomposition Classes: N - no or little integration with the soil surface; I - partial to nearly full integration with the soil surface.

** >10.16cm diameter at 1.3716m above ground and >1.8288m height--if less diameter OR height use applicable down wood type; for pinyon and juniper, use 0.3048m above ground.

*** Hard - tree is dead with most or all of bark intact; Soft - most of bark has sloughed off.

Table 11. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | – | 0-1% | 5-10% | 1-5% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | 0-1% | 0-1% | 10-30% | 5-10% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | 1-3% | 0-1% | 5-45% | 5-25% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | 5-15% | 0-1% | 5-25% | 2-10% |

| >1.4 <= 4 | 10-30% | 0-1% | – | – |

| >4 <= 12 | 40-65% | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | 10-35% | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | – | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

State 3

Pastureland

The majority of sites included within this ecological site description are not appropriate for pastures or hay due to slope, shallow soil or rock content. This State is included in this ecological site description to include those few sites that are have suitable soils and site conditions for agricultural production. All of the pasture sites visited during this project consisted mainly of tall fescue and other non-native grasses.

Community 3.1

Managed cool season grass pasture

This state is typified by tall fescue and an assortment of native and non-native vegetation dependent upon previous management (seeding), amount of previous soil erosion, grazing impacts, and adjacent vegetation and seed sources. The shift in plant community from predominately non-native grasses to a larger percentage of forbs, herbs, vines, shrubs, weeds, and seedling trees characterize this community's transition to a more wooded state. Very few sites included in this ecological site description are appropriate for managed pasture or hayland production uses. These uses are precluded by steep slopes, rock, shallow soils, and high erosion potential.

Forest overstory. not applicable

Forest understory. not applicable

Table 12. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 1-5% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 1-2% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 60-85% |

| Forb foliar cover | 10-25% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0-1% |

| Biological crusts | 0% |

| Litter | 1-5% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-1% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-1% |

| Bedrock | 0-1% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 1-10% |

Table 13. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (m) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.15 | – | 1-2% | 10-25% | 0-5% |

| >0.15 <= 0.3 | – | 1-5% | 5-50% | 5-25% |

| >0.3 <= 0.6 | – | 1-10% | 3-65% | 10-35% |

| >0.6 <= 1.4 | – | 5-15% | 0-40% | 15-45% |

| >1.4 <= 4 | – | 5-10% | – | 0-5% |

| >4 <= 12 | – | – | – | – |

| >12 <= 24 | – | – | – | – |

| >24 <= 37 | – | – | – | – |

| >37 | – | – | – | – |

Additional community tables

Table 14. Community 1.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| chestnut oak | QUMO4 | Quercus montana | Native | 8.8–28 | 30–60 | 12.7–55.9 | – |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 8.5–27.4 | 25–50 | 10.2–53.3 | – |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | 7.3–25.9 | 0–35 | 11.4–44.5 | – |

Table 15. Community 1.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| poverty oatgrass | DASP2 | Danthonia spicata | Native | 0–0.8 | 2–5 | |

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | Native | 0–0.4 | 0–2 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| Virginia springbeauty | CLVI3 | Claytonia virginica | Native | 0–0.2 | 5–25 | |

| harbinger of spring | ERBU | Erigenia bulbosa | Native | 0–0.3 | 1–10 | |

| mayapple | POPE | Podophyllum peltatum | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–10 | |

| Virginia creeper | PAQU2 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | Native | 0–0.2 | 1–3 | |

| Canadian blacksnakeroot | SACA15 | Sanicula canadensis | Native | 0.1–0.4 | 0–2 | |

| lyreleaf sage | SALY2 | Salvia lyrata | Native | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| clustered blacksnakeroot | SAOD | Sanicula odorata | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| Small's blacksnakeroot | SASM | Sanicula smallii | Native | 0.1–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| twoflower dwarfdandelion | KRBI | Krigia biflora | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| violet woodsorrel | OXVI | Oxalis violacea | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| stickywilly | GAAP2 | Galium aparine | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| feathery false lily of the valley | MARAR | Maianthemum racemosum ssp. racemosum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| hairy skullcap | SCEL | Scutellaria elliptica | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| fire pink | SIVI4 | Silene virginica | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| eastern poison ivy | TORA2 | Toxicodendron radicans | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| Virginia spiderwort | TRVI | Tradescantia virginiana | Native | 0–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| feathery false lily of the valley | MARAR | Maianthemum racemosum ssp. racemosum | Native | 0.1–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| white goldenrod | SOBI | Solidago bicolor | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| smooth Solomon's seal | POBI2 | Polygonatum biflorum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| common cinquefoil | POSI2 | Potentilla simplex | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| fringed redmaids | CACI2 | Calandrinia ciliata | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| beaked agrimony | AGRO3 | Agrimonia rostellata | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| American hogpeanut | AMBR2 | Amphicarpaea bracteata | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| woman's tobacco | ANPL | Antennaria plantaginifolia | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| green dragon | ARDR3 | Arisaema dracontium | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0–1 | |

| Christmas fern | POAC4 | Polystichum acrostichoides | Native | 0–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| Canadian honewort | CRCA9 | Cryptotaenia canadensis | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| white snakeroot | AGAL5 | Ageratina altissima | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| cutleaf toothwort | CACO26 | Cardamine concatenata | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| cornel-leaf whitetop | DOIN2 | Doellingeria infirma | Native | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| American alumroot | HEAM6 | Heuchera americana | Native | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| Jack in the pulpit | ARTR | Arisaema triphyllum | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| downy pagoda-plant | BLCI | Blephilia ciliata | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| soft agrimony | AGPU | Agrimonia pubescens | Native | 0.1–0.5 | – | |

|

Fern/fern ally

|

||||||

| rattlesnake fern | BOVI | Botrychium virginianum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| cutleaf grapefern | BODI2 | Botrychium dissectum | Native | 0–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| ebony spleenwort | ASPL | Asplenium platyneuron | Native | 0–0.4 | 0–1 | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| mapleleaf viburnum | VIAC | Viburnum acerifolium | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| mapleleaf viburnum | VIAC | Viburnum acerifolium | Native | 0.2–0.8 | 0–1 | |

|

Tree

|

||||||

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 0.2–0.4 | 1–2 | |

| chestnut oak | QUMO4 | Quercus montana | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 1–2 | |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| hophornbeam | OSVI | Ostrya virginiana | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| pignut hickory | CAGL8 | Carya glabra | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| red maple | ACRU | Acer rubrum | Native | 0.2–0.4 | 0–1 | |

|

Vine/Liana

|

||||||

| roundleaf greenbrier | SMRO | Smilax rotundifolia | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 2–4 | |

| cat greenbrier | SMGL | Smilax glauca | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

Table 16. Community 2.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (cm) | Basal area (square m/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 3.7–13.4 | 10–35 | 2.5–36.8 | – |

| chestnut oak | QUMO4 | Quercus montana | Native | 2.9–9.4 | 0–30 | 2.5–14 | – |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 2.7–8.5 | 0–20 | 2.5–17.8 | – |

| white ash | FRAM2 | Fraxinus americana | Native | 3.2–5 | 0–15 | 2.5–25.4 | – |

| red maple | ACRU | Acer rubrum | Native | 3.4–7.6 | 5–15 | 2.5–30.5 | – |

| Virginia pine | PIVI2 | Pinus virginiana | Native | 1.7–4.4 | 0–10 | 2.5–19.1 | – |

| American beech | FAGR | Fagus grandifolia | Native | 1.2–3.4 | 1–5 | 2.5–7.6 | – |

Table 17. Community 2.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| tall fescue | SCAR7 | Schedonorus arundinaceus | Introduced | 0–0.4 | 25–40 | |

| timothy | PHPR3 | Phleum pratense | Introduced | 0–0.6 | 1–10 | |

| orchardgrass | DAGL | Dactylis glomerata | Introduced | 0.1–0.5 | 0–10 | |

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | Native | 0–0.3 | 0–1 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| Johnsongrass | SOHA | Sorghum halepense | Native | 0.1–1.4 | 1–10 | |

| garlic mustard | ALPE4 | Alliaria petiolata | Introduced | 0.1–0.5 | 0–3 | |

| American pokeweed | PHAM4 | Phytolacca americana | Native | 0.4–1.2 | 0–2 | |

| American pokeweed | PHAM4 | Phytolacca americana | Native | 0.2–0.5 | 0–1 | |

| Canada thistle | CIAR4 | Cirsium arvense | Introduced | 0.1–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| queendevil | HIGR3 | Hieracium gronovii | Native | 0.1–0.9 | 0–1 | |

| rattlesnakeweed | HIVE | Hieracium venosum | Native | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| wild bergamot | MOFI | Monarda fistulosa | Native | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| twoflower dwarfdandelion | KRBI | Krigia biflora | Native | 0.1–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| common selfheal | PRVU | Prunella vulgaris | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| sand bittercress | CAPA12 | Cardamine parviflora | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| stickywilly | GAAP2 | Galium aparine | Native | 0–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| Philadelphia fleabane | ERPH | Erigeron philadelphicus | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| big chickweed | CEFOV2 | Cerastium fontanum ssp. vulgare | Introduced | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| oxeye daisy | LEVU | Leucanthemum vulgare | Introduced | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| Philadelphia fleabane | ERPH | Erigeron philadelphicus | Native | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| wild garlic | ALVI | Allium vineale | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| pussytoes | ANTEN | Antennaria | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| Indianhemp | APCA | Apocynum cannabinum | Native | 0.2–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| garden yellowrocket | BAVU | Barbarea vulgaris | Introduced | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| downy pagoda-plant | BLCI | Blephilia ciliata | Native | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| star chickweed | STPU | Stellaria pubera | Native | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| lyreleaf sage | SALY2 | Salvia lyrata | Native | 0.1–0.6 | 0–1 | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| winged sumac | RHCO | Rhus copallinum | Native | 0.7–2.6 | 0–2 | |

| smooth sumac | RHGL | Rhus glabra | Native | 0.9–1.6 | 0–2 | |

|

Tree

|

||||||

| red maple | ACRU | Acer rubrum | Native | 1.1–4 | 5–20 | |

| white ash | FRAM2 | Fraxinus americana | Native | 1.7–3.5 | 5–15 | |

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 1.2–3.8 | 1–10 | |

| sassafras | SAAL5 | Sassafras albidum | Native | 1.7–3 | 1–5 | |

| honeylocust | GLTR | Gleditsia triacanthos | Native | 2–3.4 | 0–5 | |

| black locust | ROPS | Robinia pseudoacacia | Native | 0.5–1.2 | 0–3 | |

| red maple | ACRU | Acer rubrum | Native | 0.1–0.4 | 1–3 | |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 0.2–0.5 | 0–2 | |

| sugar maple | ACSA3 | Acer saccharum | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 0–2 | |

| chokecherry | PRVI | Prunus virginiana | Native | 0.5–1.5 | 0–2 | |

| American beech | FAGR | Fagus grandifolia | Native | 0.2–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| slippery elm | ULRU | Ulmus rubra | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| American elm | ULAM | Ulmus americana | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | 0.7–2 | 0–1 | |

| chestnut oak | QUMO4 | Quercus montana | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| shagbark hickory | CAOV2 | Carya ovata | Native | 0.1–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| sassafras | SAAL5 | Sassafras albidum | Native | 0.2–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| pignut hickory | CAGL8 | Carya glabra | Native | 0.2–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| white ash | FRAM2 | Fraxinus americana | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

|

Vine/Liana

|

||||||

| Japanese honeysuckle | LOJA | Lonicera japonica | Introduced | 0.1–1.3 | 0–2 | |

Table 18. Community 3.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (m) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| tall fescue | SCAR7 | Schedonorus arundinaceus | Introduced | 0–0.6 | 35–65 | |

| timothy | PHPR3 | Phleum pratense | Introduced | 0–0.6 | 0–20 | |

| orchardgrass | DAGL | Dactylis glomerata | Introduced | 0.1–0.5 | 1–15 | |

| brome | BROMU | Bromus | Introduced | 0–0.6 | 1–15 | |

| orchardgrass | DAGL | Dactylis glomerata | Introduced | 0.1–0.5 | 1–15 | |

| Johnsongrass | SOHA | Sorghum halepense | Introduced | 0.1–0.4 | 0–5 | |

| broomsedge bluestem | ANVI2 | Andropogon virginicus | Native | 0.1–0.5 | 0–5 | |

| Johnsongrass | SOHA | Sorghum halepense | Introduced | 0.1–1 | 0–5 | |

| bentgrass | AGROS2 | Agrostis | Introduced | 0–0.3 | 0–5 | |

| green bristlegrass | SEVI4 | Setaria viridis | Introduced | 0–0.3 | 2–5 | |

| Kentucky bluegrass | POPR | Poa pratensis | Introduced | 0–0.3 | 0–3 | |

| barnyardgrass | ECCR | Echinochloa crus-galli | Introduced | 0–0.4 | 0–2 | |

| crabgrass | DIGIT2 | Digitaria | Introduced | 0–0.2 | 0–2 | |

| quackgrass | ELRE4 | Elymus repens | Introduced | 0–0.2 | 0–2 | |

| perennial ryegrass | LOPE | Lolium perenne | Introduced | 0.1–0.7 | 0–2 | |

| nimblewill | MUSC | Muhlenbergia schreberi | Introduced | 0–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | Native | 0–0.4 | 0–1 | |

| hairy bittercress | CAHI3 | Cardamine hirsuta | Introduced | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| yellow nutsedge | CYES | Cyperus esculentus | Native | 0.1–0.4 | 0–1 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| red clover | TRPR2 | Trifolium pratense | Introduced | 0.1–0.6 | 0–5 | |

| sweetclover | MELIL | Melilotus | Introduced | 0.1–0.7 | 0–2 | |

| white clover | TRRE3 | Trifolium repens | Introduced | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| hairy white oldfield aster | SYPIP3 | Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pilosum | Native | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| stickywilly | GAAP2 | Galium aparine | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| lesser burdock | ARMI2 | Arctium minus | Introduced | 0.1–0.9 | 0–1 | |

| tall buttercup | RAAC3 | Ranunculus acris | Native | 0.1–0.3 | 0–1 | |

| Canada goldenrod | SOAL6 | Solidago altissima | Native | 0.1–1.1 | 0–1 | |

| queendevil | HIGR3 | Hieracium gronovii | Native | 0.1–0.8 | 0–1 | |

| jimsonweed | DATUR | Datura | Introduced | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| lambsquarters | CHAL7 | Chenopodium album | Introduced | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| mallow | MALVA | Malva | Introduced | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| cocklebur | XANTH2 | Xanthium | Introduced | 0.2–0.9 | 0–1 | |

| common mallow | MANE | Malva neglecta | Introduced | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

| creeping jenny | LYNU | Lysimachia nummularia | Introduced | 0–0.1 | 0–1 | |

| dandelion | TARAX | Taraxacum | Introduced | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| curly dock | RUCR | Rumex crispus | Introduced | 0–0.6 | 0–1 | |

| eastern daisy fleabane | ERAN | Erigeron annuus | Native | 0.1–0.7 | 0–1 | |

| common chickweed | STME2 | Stellaria media | Introduced | 0–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| common cinquefoil | POSI2 | Potentilla simplex | Native | 0.1–0.2 | 0–1 | |

| chicory | CIIN | Cichorium intybus | Introduced | 0.2–0.9 | 0–1 | |

|

Vine/Liana

|

||||||

| field bindweed | COAR4 | Convolvulus arvensis | Introduced | 0.1–0.8 | 0–1 | |

Interpretations

Animal community

Hard mast production on these ecological sites is a key influence to the natural animal community and provides a critical food source for many wildlife species. White oak acorns are a preferred and valuable, although periodically, inconsistent source of wildlife food. More than 180 species of wildlife use oak acorns as food including black bears, cotton-tail rabbit, white-tailed deer, raccoons, blue jays, crows, red-headed woodpeckers, northern bobwhite, ruffed grouse, wild turkey, quail, ducks, and multiple species of mice, chipmunks and squirrels. Deer utilize white oak twigs and foliage as browse especially in areas of regeneration, such as clear cuts. Occasionally, dried oak leaves are also eaten by white-tailed deer during winter months. In some areas, the abundance of fall mast crops can affect wildlife reproductive success during the following year. Acorns are a particularly important food source for black bears in many areas. Acorn crop failures have been correlated with increases in bear related damage to gardens, crops, livestock, and beehives (Sork, V. 1983).

Heavy crops of chestnut oak acorns tend to be sporadic, but during production years, the sweet-tasting acorns are relished by numerous upland wildlife species, including white-tailed deer, squirrels, chipmunks, mice, and wild turkey. Deer will occasionally browse young chestnut oak sprouts, especially the first year following cutting or burning. Small birds and mammals, as well as insects such as bees, use chestnut oak cavities for nesting. In a survey of 31 oak and hickory stands in the Appalachian Mountains, a disproportionate share of cavities in chestnut oaks were utilized by wildlife species (Andrew, C. 1983). Although no species-specific study was found, this information raises the question of Indiana bats possibly utilizing chestnut oak trees for roosting sites and the need to protect this federally endangered species on these ecological sites.

Black oak prefers moist, rich, well-drained soils, but this species has the ability to adapt to many ecological sites and can tolerate dry hillsides and poorer soil sites. As with other oaks, black oak acorns are an important food for squirrels, white-tail deer, mice, and many species of birds. Like chestnut oak, studies are available that highlight this trees benefit to wildlife by providing suitable nesting cavities and roosting areas (DeGraaf, R. 1985).

Scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea) is a quick-growing tree adaptable to a variety of soils and can be a prolific acorn producer benefiting many species of wildlife.

Red maple is a subclimax species that quickly occupies forest openings with its prolific sprouting and fast growth. Although usually considered an undesirable tree by foresters, red maple is a source of wildlife food. White-tailed deer and elk will browse on it during winter months and stockpiling timber harvesting slash can provide a source of winter food for these animals. Maples provide cover for many species of wildlife including providing nesting cavities for a variety of birds. Researchers have documented that screech owls, pileated woodpeckers, and common flickers frequently nest in maple cavities (Hardin, K. 1977).

High in protein and fat, pignut hickory nuts are highly palatable and an important food source for many mammals (bears, foxes, raccoons, mice, wood rats, squirrels, rabbits) as well as wild turkey, common crow, blue jay, wood ducks, ring-necked pheasants, northern bobwhite, nuthatches, woodpeckers, and sapsuckers (Smalley, G. 1990).

Other hickory species produce food for many species of wildlife including foxes, rabbits, raccoons, chipmunks, turkeys, songbirds, and black bears. Even the bark and flowers can be consumed by wildlife.

Other beneficial tree species

Eastern hophornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), short-lived, small tree found in the understory of these sites, and provides wildlife with a limited seed source (Hall, 1977).

Sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum) flowers are attractive to butterflies and other insects. Natural hollows in these trees are refuge for climbing reptiles and amphibians, bats, and other small wildlife. Old fall webworm tents attract invertebrates that birds often eat during late fall and winter. It may also provide a key source of honey in some areas.

Sassafras can be found on a wide range of soil types and ecological sites. The bark and twigs of sassafras are browsed by deer in the winter and during the spring and summer, deer utilize the leaves and new growth.

Almost every part of the flowering dogwood tree, including the fruit, leaves, flowers, twigs, and bark, can be utilized by wildlife as a food source. The fruit is actually poisonous to humans, but relished by many species of birds. Over 35 species of birds, including ruffed grouse, bob-white quail, and wild turkey, utilize the fruit as a food source. Chipmunks, foxes, skunks, rabbits, deer, beaver, black bears, and squirrels also eat dogwood fruits. Foliage and twigs are browsed heavily by deer and rabbits. For landowners wishing to maximize wildlife habitat, controlled burns in the spring can improve the quality (protein and phosphoric acid content) and quantity of dogwood browse.

Endangered Species and Species of Concern

The Indiana bat (Myotis sodalist) is a federally endangered species that can be found on these ecological sites. This species has declined dramatically mostly due to human activity. Diseases, such as white-nose syndrome, and the increased use of pesticides are also detrimental factors. Indiana bat maternity colonies are found under loose tree bark and may consist of up to 100 bats. This roosting behavior makes the mothers and young highly vulnerable to tree removal during the summer months. Females typically roost under loose bark of dying or dead trees and maternity roosts are often located where they can receive at least a half of day of sunlight. This characteristic makes forest edges and forest canopy gap areas highly desirable Indiana bat habitat. Females will have a single “pup” in late June or early July and the pups will be able to fly in 4 to 6 weeks. All clearing or thinning of trees should be conducted to minimize potential impacts to roosting bats and local wildlife agencies can assist landowner with site evaluations and further information.

In October of 2013, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) published a proposal to list the northern long-eared bat as endangered throughout its range under the Endangered Species Act. The potential range of the northern long-eared bat includes most of the forested areas of Kentucky including the oak-hickory forests within the Knobs-Norman Upland Ecoregion. According to USFWS publications, northern long-eared bats emerge at dusk and fly through the understory of forested hillsides and ridges. Food sources are found through echolocation and include moths, flies, leafhoppers, caddisflies, and beetles. This bat can also consume motionless insects directly from vegetation and water surfaces. Like the Indiana bat, this tiny mammal roost in trees. An absence of disturbance during the spring and summer maternity periods is critical for continued survival of this species, so forest clearing or thinning should be conducted during the winter months to avoid accidental destruction of maternity roosts.

Appalachian Cottontails in Kentucky

Managed in Kentucky as a game species, the Appalachian cottontail (Sylvilagus obscurus or S. transitionalis obscurus) is found in habitats that have an ericaceous understory, such as blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) and evergreen species of greenbrier (Smilax spp.). Research has shown that Appalachian cottontails are found in higher elevation wooded habitats unlike the more common eastern cottontail which prefers fields and farmlands (Chapman et. al. 1992). The distribution of Appalachian cottontails was not well documented in Kentucky prior to a study conducted from 1991 to 1995. This effort found the species in the eastern Knobs region, specifically Lincoln and Boyle Counties.

Known locally as the gray rabbit, brush rabbit or woods rabbit, this species is differentiated from the eastern cottontail by having one or more the following characteristics: a darker pelage, a black strip around the outer ear edge, and a black spot on the forehead (Chapman et. al. 1992). Hunters have reported differences in running behavior and habitat use between the two species as well. (Sole, 1999)

Recreational uses

These ecological sites are of great value for many recreational uses including hiking, hunting, wildlife viewing, wildflower identification, research and education, and nature photography. The majority of sites visited for this project are located in protected areas such as state-owned wildlife management areas, state forests, and Kentucky State Nature Preserve Commission lands. Another key site utilized for this project was the Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest near Louisville, Kentucky. These areas focus on recreation and outdoor education. The importance of these ecological sites for these purposes are significant.

Wood products

Most of the ecological sites visited had been grazed, cleared, or undergone repeated timber harvesting. Forest composition was predominately a younger canopy layers (30-60 years) whose value for timber and wood products had been reduced due to lack of forest stand management. Species composition (high quality oak) and tree quality on most sites was moderate to poor. Oak regeneration was usually present within these stands, but desirable timber species were being outpaced by quick growing and shade tolerate trees. To improve the quantity and quality of forest products produced on these sites, application of forest stand improvement principles are recommended.

County level soil surveys developed by USDA-NRCS can provide historic woodland management and productivity data specific to soil type.

Other products

Most sites included in this ecological site description were not suitable traditional Kentucky agricultural practices such as row crop or hay production. However, these sites can be very valuable for managed timber production or alternative forest products. Income opportunities from the production of timber, hunting leases or alternative forest products can offer private landowners alternative revenue streams.

Privately owned sites visited during this project had generally been cut over multiple times with minimal forestry practices applied. Sites consisted of lower quality trees with minimal timber sale value. However, many of these properties could be suitable for alternative forest products. For example, Shiitake mushroom may provide landowners with an economic return on small diameter woodlands that would otherwise be damaged by unmanaged grazing, utilized as firewood, or simply ignored. Hardwood oak, hickory, and maple logs 3 to 8 inches in diameter are ideal for growing Shiitake mushrooms. Private landowners in this region are growing this crop successfully and production details should be investigated based on site-specific characteristics.

Another non-timber woodland product that could be considered is wild ginseng. Kentucky is a leading exporter of wild ginseng (5 to 8 million dollars annually) and private landowner production in the Commonwealth has been increasing. This medicinal herb requires the cooler north or east-facing slopes of more shaded woodlands. The forest understory should be open to allow for good air circulation and slopes of 15 to 40 percent are often recommended in literature. The woodland should be protected and the soil productive enough to include native understory plants such as Solomon’s seal, mayapples, and trilliums. Landowners interested in investigating alternative agro-forestry products should contact their state extension service or local university for assistance.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Ecological states and phases and the plant species lists were developed utilizing low-intensity reconnaissance followed by selective medium or high-intensity monitoring. Medium and high intensity monitoring was conducted on 20 x 20 meter plots.

Low intensity data collection included verification of soil mapping, ocular estimates of cover, development of plant lists for species on site, landscape and individual plant photos, and the development of draft ecological site concepts based on these field observations. Additional data collection on higher-quality sites included verification of soils (soil profile description), spatial coordinates, expanded plant identification lists, additional field notes, and evaluations of plant communities on similarly mapped soils. Photos of individual plants, transect lines within the plots, and landscape views were recorded.

Plot data was obtain on public land: Bernheim Research Forest, Jefferson Memorial Forest, Knobs State Forest, Marion State Forest and Wildlife Management Area. These sites were selected due to the absence of logging and grazing for many decades. Often these sites also had previous ecological research conducted on them or at least had basic information available on previous land uses, species lists, and disturbance regimes. These protected areas also provided rare examples of high-quality older-growth sites with protected understories.

Private lands visited provided varying examples of disturbance depending on the landowner’s purpose for owning the land.

Most private lands visited for this project were in a successional state, versus a reference state, as the property had been cleared, repeatedly logged, or grazed. Impacts on these properties were varied, often repeated, sometimes unknown (new owners) and is was often difficult to accurately interpret what was occurring with regards to the great variation in tree and understory species found on these sites.

Species lists were developed with assistance of Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission botanists. Tree identification and production data on plots were developed with the assistance of a private-lands forester with the Kentucky Division of Forestry.

Type locality

| Location 1: Jefferson County, KY | |

|---|---|

| Latitude | 85° 47′ 24″ |

| Longitude | 38° 5′ 9″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Jefferson Memorial Forest Aspect: SW Mapunit: Carpenter silt loam, 20-50% |

| Location 2: Bullitt County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 37′ 48″ |

| Longitude | 37° 53′ 28″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Bernheim Research Forest. Aspect: E Mapunit: Lenberg-Carpenter Complex, 20-40% |

| Location 3: Bullitt County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 36′ 43″ |

| Longitude | 37° 53′ 41″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Bernheim Research Forest. Aspect: S Mapunit: Lenberg-Carpenter complex, 20-40% |

| Location 4: Jefferson County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 47′ 14″ |

| Longitude | 38° 4′ 56″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Jefferson Memorial Forest. Aspect: NE Mapunit: Carpenter silt loam, 20-50% |

| Location 5: Jefferson County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 47′ 47″ |

| Longitude | 38° 5′ 27″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Jefferson Memorial Forest Aspect: N Mapunit: Carpenter silt loam, 20-50% |

| Location 6: Bullitt County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 39′ 27″ |

| Longitude | 37° 52′ 40″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Knobs State Forest Aspect: South Mapunit: Lenberg-Carpenter complex, 20-40% |

| Location 7: Marion County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 8′ 43″ |

| Longitude | 37° 32′ 8″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Marion County State Forest and Wildlife Management Area Aspect: SW Mapunit: Carpenter-Lenberg complex, 20-45% |

| Location 8: Bullitt County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 39′ 39″ |

| Longitude | 37° 52′ 23″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Knobs State Forest Aspect: NW Mapunit: Lenberg-Carpenter Complex, 20-40% |

| Location 9: Marion County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 9′ 15″ |

| Longitude | 37° 31′ 53″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Marion County State Forest and Wildlife Management Area Aspect: NE Mapunit: Carpenter-Lenberg complex, 20-45% |

| Location 10: Bullitt County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 35′ 57″ |

| Longitude | 37° 53′ 27″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Bernheim Research Forest. Aspect: NW Mapunit: Lenberg-Carpenter complex, 20-40% |

| Location 11: Bullitt County, KY | |

| Latitude | 85° 37′ 42″ |

| Longitude | 37° 54′ 30″ |

| General legal description | Located within the Bernheim Research Forest Aspect: N Mapunit: Lenberg-Carpenter complex, 20-40% |

Other references

Abrams, M.D. and G.J.Nowacki. 2008. Native Americans as active and passive promoters of mast and fruit trees in the eastern USA. The Holocene 18.7. pp. 1123-1137.

Barbour, M.G., J.H. Burk, W.D. Pitts, F.S. Gilliam, and M.W. Schwartz. 1999. Terrestrial Plant Ecology (ed. 3). Benjamin/Cummings, Inc., Menlo Park, California.

Braun, E.L. 1950. Deciduous forests of Eastern North America. Blakinston Co, Pennsylvania. Reprinted in 2001 by Blackburn Press, Caldwell, New Jersey.

Carey, Andrew B. 1983. Cavities in trees in hardwood forests. In: Davis, Jerry W.; Goodwin, Gregory A.; Ockenfeis, Richard A., technical coordinators. Snag habitat management: proceedings of the symposium; 1983 June 7-9; Flagstaff, AZ. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-99. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 167-184. [17833]

Clark, R.C. and T.J. Weckman. 2008. Annotated catalog and atlas of Kentucky woody plants. Castanea, Occasional Paper in Eastern Botany No. 3: 1–114.

Cleland, D. T., J. A. Freeouf, J. E. Keys, Jr., G. J. Nowacki, C. A. Carpenter, and W. H. McNab. 2007. Ecological Subregions: Sections and Subsections of the Conterminous United States.

GTR-WO-76C-1. http://fsgeodata.fs.fed.us/other_resources/ecosubregions.html.

Comer, P., D. Faber-Langendoen, R. Evans, S. Gawler, C. Josse, G. Kittel, S. Menard, M. Pyne,

M. Reid, K. Schulz, K. Snow, and J. Teague. 2003. Ecological Systems of the United States: A Working Classification of U.S. Terrestrial Systems. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia.

DeGraaf, Richard M; Shigo, Alex L. 1985. Managing cavity trees for wildlife in the Northeast. Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-101. Broomall, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station.

Delcourt, P.A. and H.R Delcourt. 1998. The influence of prehistoric human-set fires on oak- chestnut forests in the southern Appalachians. Castanea 63:337-345.

Evans, M., and G. Abernathy. 2008. Presettlement land cover of Kentucky. Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission, Frankfort, Kentucky, USA.

Fenneman, N.M. 1917. Physiographic subdivisions of the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Vol. 3(1). pp. 17 -22.

Fenneman, N.M. 1938. Physiography of Eastern United States. McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York.

Guyette, R.P. and D.C. Dey. 2000. Humans, topography, and wildland fire: the ingredients for long-term patterns in ecosystems. Pp. 28-35 in D.A. Yaussy (ed.). Proceedings of the workshop on fire, people, and the central hardwoods landscape. General Technical Report NE-274.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experimentation Station. Radnor, Pennsylvania.

Guyette, R.P., M.C. Stambaugh, D.C. Dey and R. Muzika. 2011. Predicting fire frequency with chemistry and climate. Ecosystems Published online: DOI: 10.1007/s10021-011-9512-0.

Halls, Lowell K. 1977. Southern fruit-producing woody plants used by wildlife. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report SO-16. Southern Forest Experiment Station, New Orleans, LA.

Hardin, Kimberly I.; Evans, Keith E. 1977. Cavity nesting bird habitat in the oak-hickory forests--a review. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-30. St. Paul, MN: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station. 23 p.

Jennings, M.D., Faber-Langedoen, D., Loucks, O.L., Peet, R.K. and Roberts, D. 2009. Standards for associations and alliances of the U.S. National Vegetation Classification. Ecological Monographs, 79(2), 2009, pp. 173–199.

Johnson, Paul S. 1992. Oak overstory/reproduction relations in two xeric ecosystems in Michigan. Forest Ecology and Management. 48: 233-248.

Kartesz, J.T., The Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2011. North American Plant Atlas (http://www.bonap.org/MapSwitchboard.html). Chapel Hill, N.C. [maps generated from Kartesz,

J.T. 2010. Floristic Synthesis of North America, Version 1.0. Biota of North America Program (BONAP). (in press)].

Kentucky Division of Geographic Information. 2004. Kentucky 2001 Anderson level III land cover. Kentucky Division of Geographic Information, Frankfort, Kentucky, USA.

Keever, C. 1978. A study of the mixed mesophytic, western mesophytic, and oak chestnut regions of the eastern deciduous forest including a review of the vegetation and sites recommended as potential natural landmarks. Millersville State College, Pennsylvania.

Kentucky Geological Survey, Geospatial Analysis Section, Digital Mapping Team. 2004. Geologic formations. Kentucky Geological Survey, Lexington, Kentucky, USA.

Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission. 2009. Natural communities of Kentucky. Frankfort, KY

Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission. 2011. Kentucky natural areas inventory dataset. Frankfort, KY.

Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission. 2012. Kentucky natural heritage database. Frankfort, KY.

Lawless, P. J., Baskin, J. M. and C. C. Baskin. 2006. Xeric Limestone Prairies of Eastern United States: Review and Synthesis. The Botanical Review 73(4): 303–325. The New York Botanical Garden.

NatureServe. 2006. International Ecological Classification Standard: Terrestrial Ecological Classifications. NatureServe Central Databases. Arlington, VA USA

NatureServe. 2014. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer.

McNab, W.H. and P.E. Avers. 1994. Ecological subregions of the United States. U.S. Forest Service. Prepared in cooperation with Regional Compilers and the ECOMAP Team of the Forest Service.

McNab, W.H, D. T. Cleland, J. A. Freeouf, J. E. Keys, Jr., G. J. Nowacki, and C. A. Carpenter. 1997. Description of “Ecological Subregions: Sections of the Conterminous United States”.

Noss, R. F. 1983. A regional landscape approach to maintain biodiversity. BioScience 33(11): 700-706.

Pickett, S.T.A. and P.S. White. 1985. Patch dynamics: a synthesis. In: S.T.A. Pickett and P.S. White. The ecology of natural disturbance and patch dynamics. New York: Academic Press: 371-384.

Pyne, S.J. 1982. Fire in America: a cultural history of wildland and rural fire. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Quarterman, E. and R.L. Powell. 1978. Potential ecological/geological natural landmarks on the Interior Low Plateaus. pp. 7-73. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. Quarterman,

Rooney, T.P., S.M. Wiegmann, D.A. Rogers and D.M. Waller. 2004. Biotic impoverishment and homogenization in unfragmented forest understory communities. Conservation Biology (in press).

Slone, T. and Wethington, T. 2001. Kentucky's Threatened and Endangered Species. Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, Frankfort, KY.

Smalley, Glendon W. 1990. Carya glabra (Mill.) Sweet pignut hickory. Silvics of North America. Vol. 2. Hardwoods. Agric. Handbook 654. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 198-204.

Stambaugh, M.C. and R.P. Guyette. 2008. Predicting spatio-temporal variability in fire return intervals with a topographic roughness index. Forest Ecology and Management 254:463-473.

Stritch, L.R. 1990. Landscape-scale restoration of barrens-woodland within the oak-hickory forest mosaic. Restoration & Management Notes 8: 73-77.

Sweeney, J.M., ed. 1990. Management of dynamic ecosystems. North Cent. Sect., The Wildl. Soc., West Lafayette, Ind.

Sole, Jeffery. 1999. Distribution and Habitat of Appalachian Cottontails in Kentucky. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of Southeastern Association Fish and Wildlife Agencies 53:444-448.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil survey of Bullitt and Spencer Counties, KY.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil survey of Casey County, KY.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil survey of Garrard and Lincoln Counties, KY.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil survey of Hardin and Larue Counties, KY.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil survey of Jefferson County, KY.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil survey of Marion County, KY.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil survey of Nelson County, KY.

United States Department of Agriculture-Forest Service, Agriculture Handbook 654, Silvics of North America.

Sork, Victoria L.; Stacey, Peter; Averett, John E. 1983. Utilization of red oak acorns in non-bumper crop year. Oecologia. 59: 49-53.

Woods, A.J., Omernik, J.M., Martin, W.H., Pond, G.J., Andrews, W.M., Call, S.M, Comstock, J.A., and Taylor, D.D., 2002, Ecoregions of Kentucky (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, VA., U.S. Geological Survey (map scale 1:1,000,000).

Zollner, D., M.H. MacRoberts, B.R. MacRoberts, & D. Ladd. 2005. Endemic vascular plants of the Interior Highlands, U.S.A. Sida 21:1781-1791.

Contributors

Anita Arends

Approval

Greg Schmidt, 10/01/2024

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 04/18/2025 |

| Approved by | Greg Schmidt |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-