Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F149BY008MA

Very Wet Outwash

Last updated: 9/17/2024

Accessed: 03/03/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 149B–Long Island-Cape Cod Coastal Lowland

149B—Long Island-Cape Cod Coastal Lowland

This area is in the Embayed Section of the Coastal Plain Province of the Atlantic Plain. It is part of the partially submerged coastal plain of New England. It is mostly an area of nearly level to rolling plains, but it has some steeper hills (glacial moraines). Ridges border the lower plains. The Peconic and Carmans Rivers are on the eastern end of Long Island. The parts of this area in Massachusetts and Rhode Island have no major rivers. This entire area is made up of deep, unconsolidated glacial outwash deposits of sand and gravel. A thin mantle of glacial till covers most of the surface. Some moraines form ridges and higher hills in this area of generally low relief. Sand dunes and tidal marshes are extensive along the coastline.

Classification relationships

USDA-NRCS (USDA, 2006):

Land Resource Region (LRR): S—Northern Atlantic Slope Diversified Farming Region

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 149B—Long Island-Cape Cod Coastal Lowland

USDA-FS (Cleland et al., 2007):

Province: 221 Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province

Section: 221A Lower New England

Subsection: 221Ab Cape Cod Coastal Lowland and Islands

Subsection: 221An Long Island Coastal Lowland and Moraine

Ecological site concept

This site consists of very deep, very poorly drained soils that formed in sandy and gravelly glaciofluvial deposits. They are on toeslopes in wet depressions on outwash plains and deltas, along drainage ways. Representative soils are Rainberry and Wareham.

Many of the plant communities are considered maritime if influenced by salt spray from coastal storms or coastal if only influenced by the coastal climate. The representative plant communities are dominated by more open plant communities e.g., “shrub swamps” (Swain and Kearsley 2001); and “shallow/deep emergent marshes” (Swain and Kearsley 2001). Eutrophication can converts these site to common reed marshes.

Associated sites

| F149BY007NY |

Moist Outwash Moist Outwash |

|---|

Similar sites

| F149BY004NY |

Wet Lake Plain Wet Lake Plain |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Vaccinium corymbosum |

| Herbaceous |

Not specified |

Physiographic features

The site occurs in wet landforms occurring in till and outwash plains, and may be subject to frequent flooding/ponding.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Outwash plain

> Kettle

(2) Till plain > Depression (3) Drainageway (4) Terrace |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to very high |

| Flooding frequency | None to very frequent |

| Ponding frequency | None to frequent |

| Elevation | 1,000 ft |

| Slope | 3% |

| Water table depth | 12 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

Coastal regions' climate generally considered maritime, experiences a more moderate climate than inland, i.e., cooler summers and warmer winters and delayed onset of spring. However, coastal regions do experience the brunt of extreme weather such as nor'easters and tropical storms, e.g., hurricanes. Occupying a low position in the landscape, depressions may experience cold air pockets.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 157-197 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 207-219 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 43-49 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 156-204 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 199-223 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 43-50 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 179 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 212 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 46 in |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 3. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) HYANNIS [USC00193821], Hyannis, MA

-

(2) EAST WAREHAM [USC00192451], East Wareham, MA

-

(3) WANTAGH CEDAR CREEK [USC00308946], Seaford, NY

-

(4) OCEANSIDE [USC00306138], Oceanside, NY

-

(5) SETAUKET STRONG [USC00307633], East Setauket, NY

Influencing water features

The Wet outwash Ecological Site are typified generally as wet depressions.

Wetland description

National Wetland Inventory would classify Wet Outwash Ecological Site as Palustrine with a seasonally saturated water regime (Cowardin et. 1979)

Soil features

The site consists of moderately to very deep, somewhat to very poorly drained soils that formed in glacially deposited parent materials. The representative soils are Berryland, Brockton, Rainberry, Walpole, and Wareham.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Glaciofluvial deposits

–

igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rock

(2) Glaciolacustrine deposits (3) Till |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Loamy sand (2) Mucky loamy sand (3) Mucky loamy coarse sand (4) Mucky sand (5) Sandy loam (6) Coarse sand |

| Family particle size |

(1) Coarse-loamy (2) Sandy |

| Drainage class | Very poorly drained to somewhat poorly drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow to moderate |

| Depth to restrictive layer | 20 – 72 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 9% |

| Available water capacity (Depth not specified) |

2 – 7 in |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

3.5 – 7.3 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

30% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

20% |

Ecological dynamics

[Caveat: The vegetation information contained in this section and is only provisional, based on concepts, not yet validated with field work.*]

The vegetation groupings described in this section are based on the terrestrial ecological system classification and vegetation associations developed by NatureServe (Comer 2003). Terrestrial ecological systems are specifically defined as a group of plant community types (associations) that tend to co-occur within landscapes with similar ecological processes, substrates, and/or environmental gradients. They are intended to provide a classification unit that is readily mappable, often from terrain and remote imagery, and readily identifiable by conservation and resource managers in the field. A given system will typically manifest itself in a landscape at intermediate geographic scales of tens-to-thousands of hectares and will persist for 50 or more years. A vegetation association is a plant community that is much more specific to a given soil, geology, landform, climate, hydrology, and disturbance history. It is the basic unit for vegetation classification and recognized by the US National Vegetation Classification (US FDGC 2008; USNVC 2017). Each association will be named by the diagnostic and often dominant species that occupy the different height strata (tree, shrub, and herb). Within the NatureServe Explorer database, ecological systems are numbered by a community Ecological System Code (CES) and individual vegetation associations are assigned an identification number called a Community Element Global Code (CEGL).

[*Caveat] The information presented is representative of very complex vegetation communities. Key indicator plants and ecological processes are described to help inform land management decisions. Plant communities will differ across the MLRA because of the naturally occurring variability in weather, soils, and geography. The reference plant community is not necessarily the management goal. The drafts of species lists are merely representative and are not botanical descriptions of all species occurring, or potentially occurring, on this site. They are not intended to cover every situation or the full range of conditions, species, and responses for the site.

The Very Wet Outwash ecological site, set in wet basins with saturated hydrologic conditions, is characterized by wetland plant communities with coastal affinities from Long Island, New York, north to Cape Cod, Massachusetts. These plant communities are mostly within the Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Basin Peat Swamp system (CES203.522). The prevailing ecological processes are related to wetness, but also coastal influences, such as a coastal climate and storms, and if within close proximity to the coast, maritime effects of wind exposure, salt spray, and sand movement. These wetlands are quite varied and may be wet thickets dominated by hignbush blueberry (Vaccinium coryumbosum), swamp azalea (Rhododendron viscosum), and sweet pepperbush (Cletha alnifolia) or buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) and swamp loosestrife (Decodon verticillatus) or marshes of cattails (Typha spp.). Other swamp dominants may be red maple (Acer rubrum) and/or Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides). Threats include drainage and conversion to develped land, invasives such as common reed (Phragmites australis). (Source: NatureServe 2018 [accessed 2019], USNVC 2017 [accessed 2019]).

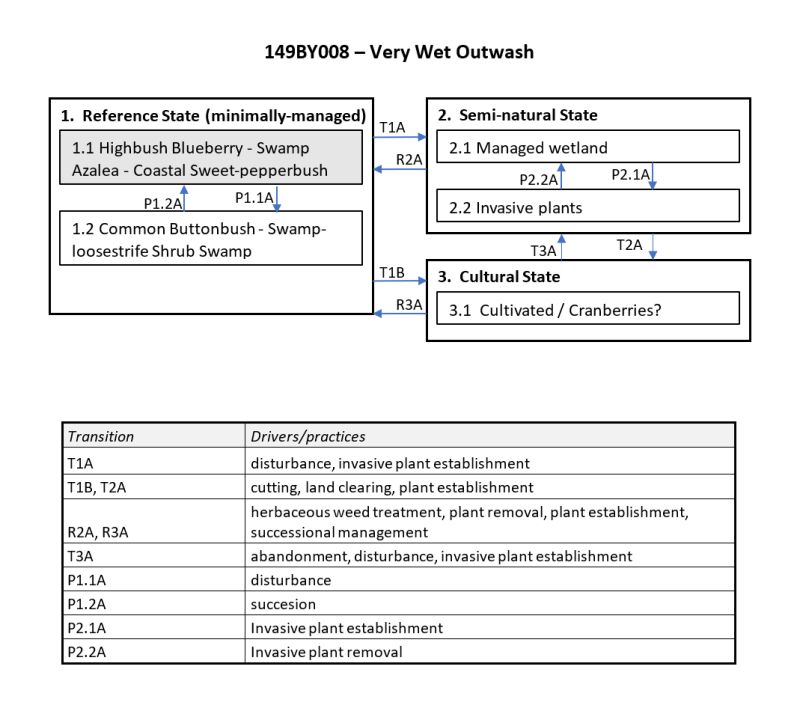

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State (Very Wet Outwash)

The predominant plant communities of the Very Wet Outwash ecological site’s Reference State (minimally-managed) include: • Blueberry Wetland Thicket, (Highbush Blueberry - Swamp Azalea - Coastal Sweet-pepperbush Acidic Peatland), {Vaccinium corymbosum - Rhododendron viscosum - Clethra alnifolia Acidic Peatland], - CEGL006371 • Northeastern Buttonbush Shrub Swamp, (Common Buttonbush - Swamp-loosestrife Shrub Swamp), [Cephalanthus occidentalis - Decodon verticillatus Shrub Swamp], - CEGL006069 Other common plant communities in more enriched conditions may include: • Eastern Cattail Marsh, Cattail (Narrowleaf Cattail, Broadleaf Cattail) - (Bulrush species) Eastern Marsh), [Typha (angustifolia, latifolia) - (Schoenoplectus spp.) Eastern Marsh], - CEGL006153 • Lower New England Red Maple Swamp Forest, (Red Maple / Swamp Azalea - Coastal Sweet-pepperbush Swamp Forest), [Acer rubrum / Rhododendron viscosum - Clethra alnifolia Swamp Forest], - CEGL006156 • Coastal Plain Atlantic White Cedar Swamp Forest, (Coastal Plain Atlantic White Cedar Swamp Forest), [Chamaecyparis thyoides / Ilex glabra - Rhododendron viscosum Swamp Forest], - CEGL006188 (Source: NatureServe 2018 [accessed 2019], USNVC 2017 [accessed 2019]).

Community 1.1

Highbush Blueberry - Swamp Azalea - Coastal Sweet-pepperbush Thicket

Blueberry Wetland Thicket, (Highbush Blueberry - Swamp Azalea - Coastal Sweet-pepperbush Thicket), [Vaccinium corymbosum - Rhododendron viscosum - Clethra alnifolia Thicket], - CEGL006371 Typically, these associations occurs in small open basins, closed sandplain basins, and seasonally flooded zones within larger wetlands. It may also form as a result of beaver activity. This vegetation can occur on the margins of Coastal Plain ponds. This community is influenced by a strongly fluctuating water table with flooded conditions in spring and early summer followed by a drop in the water table below soil surface usually by late summer. Dominant shrubs include highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), winterberry (Ilex verticillata), and swamp azalea (Rhododendron viscosum). Scattered red maple (Acer rubrum) are occasional. Maleberry (Lyonia ligustrina) and buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) are characteristic. Associated shrub species may include sweet pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia), rosy meadowsweet (Spiraea tomentosa), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), inkberry (Ilex glabra), swamp doghobble (Leucothoe racemosa), swamp loostriffe (Decodon verticillatus), sheep laurel (Kalmia angustifolia), smooth alder (Alnus serrulata), sweetgale (Myrica gale), and chokeberry (Aronia spp.). Herbaceous composition is variable; some of the more typical species include cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea), royal fern (Osmunda regalis), marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris), sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), water arum (Calla palustris), northern water horehound (Lycopus uniflorus), Virginia marsh St. John’swort (Triadenum virginicum), fowl mannagrass (Glyceria striata), rice cutgrass (Leersia oryzoides), threeway sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum), common softrush (Juncus effusus), and Virginia chainfern (Woodwardia virginica). A layer of peatmoss (Sphagnum spp. may occur, including: Sphagnum fimbriatum, Sphagnum rubellum, Sphagnum magellanicum, Sphagnum fallax, and Sphagnum viridum. (Source: NatureServe 2018 [accessed 2019], USNVC 2017 [accessed 2019]). Cross-referenced plant community concepts (typically by political state): Shrub Swamp (Swain 2016) [MA] Shrub Swamp (Edinger et al. 2014) [NY] Blueberry wetland thicket (Sneddon et al. 2010) [Cape Cod National Seashore]

Community 1.2

Common Buttonbush - Swamp-loosestrife Shrub Swamp

Northeastern Buttonbush Shrub Swamp, (Common Buttonbush - Swamp-loosestrife Shrub Swamp), [Cephalanthus occidentalis - Decodon verticillatus Shrub Swamp], - CEGL006069 These swamps can experience prolonged or semipermanent flooding for much of the growing season, with water tables receding below the soil surface only during drought or very late in the growing season. They occur in a variety of environmental settings. Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) is dominant and often monotypic. Occasional associates depend on the environmental setting and most often occur in drier areas. They include highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), swamp azalea (Rhododendron viscosum), and possibly red maple (Acer rubrum) and dogwoods (Cornus spp). closer to upland borders or swamp loostriffe (Decodon verticillatus), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), and white meadowsweet (Spiraea alba var. latifolia) in more stagnant basins. Herbaceous species tend to be sparse but can include Canada mannagrass (Glyceria canadensis), threeway sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum), tussock sedge (Carex stricta), common woolsedge (Scirpus cyperinus), marshfern (Thelypteris palustris), rice cutgrass (Leersia oryzoides), European sweetflag (Acorus calamus), European waterplantain (Alisma plantago-aquatica), smartweeds/knitweeds (Polygonum spp.), (bur-reeds (Sparganium spp)., and possibly floating or submerged aquatic species such as duckweed (Lemna minor), pondweed (Potamogeton spp,) and variagated yello pondlily (Nuphar variegata). Bryophytes, if present, cling to shrub bases and include warnstofia moss (Warnstorfia fluitans), dreplanoclatus moss (Drepanocladus aduncus), or peatmoss (Sphagnum fallax). In disturbed areas, these wetland may be invaded by purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). (Source: NatureServe 2018 [accessed 2019], USNVC 2017 [accessed 2019]). Cross-referenced plant community concepts (typically by political state): Shrub Swamp (Swain 2016) [MA] Shrub Swamp (Edinger et al. 2014) [NY] Northeastern Buttonbush Shrub Swamp (Sneddon et al. 2010) [Cape Cod National Seashore]

Pathway P1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Disturbance, greater fire frequency, coastal proximity

Pathway P1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Succession, reduced fire frequency

State 2

Semi-natural State

Vegetation on lands somewhat conditioned by land use, e.g., managed native plant communities or invasive plant communities.

Community 2.1

Managed wet woodland/thicket

Community 2.2

Invasive Plant Community

purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), common reed (Phragmites australis)

Pathway P2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Invasive plant establishment

Pathway P2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Invasive plant management

Conservation practices

| Invasive Plant Species Control |

|---|

State 3

Cultural State

Landscapes heavily conditioned by land use, e.g., Plantations/gardens/cultivation(?)

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Disturbance, invasive plant establishment

Conservation practices

| Forest Land Management |

|---|

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Cutting, land clearing, plant establishment

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Land Clearing |

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Herbaceous weed treatment, plant removal, plant establishment, successional management

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Restoration and Management of Natural Ecosystems | |

| Native Plant Community Restoration and Management | |

| Forest Land Management | |

| Invasive Plant Species Control | |

| Monitoring and Evaluation |

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Cutting, land clearing, plant establishment

Conservation practices

| Land Clearing | |

|---|---|

| Invasive Plant Species Control | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 1

Herbaceous weed treatment, plant removal, plant establishment, successional management

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Restoration and Management of Natural Ecosystems | |

| Native Plant Community Restoration and Management | |

| Invasive Plant Species Control | |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

Abandonment, disturbance, invasive plant establishment

Additional community tables

Interpretations

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Site Development and Testing Plan

Future work is needed, as described in a project plan, to validate the information presented in this provisional ecological site description. Future work includes field sampling, data collection and analysis by qualified vegetation ecologists and soil scientists. As warranted, annual reviews of the project plan can be conducted by the Ecological Site Technical Team. A final field review, peer review, quality control, and quality assurance reviews of the ESD are necessary to approve a final document.

References

-

Cleland, D.T., J.A. Freeouf, J.E. Keys, G.J. Nowacki, C. Carpenter, and W.H. McNab. 2007. Ecological Subregions: Sections and Subsections of the Coterminous United States. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report WO-76. Washington, DC. 1–92.

-

Comer, P., D. Faber-Langendoen, R. Evans, S. Grawler, C. Josse, G. Kittel, S. Menard, M. Pyne, M. Reid, K. Schultz, K. Snow, and J. Teague. 2003. Ecological Systems of the United States: A Working Classification of U.S. Terrestrial Systems. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia..

-

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. LaRoe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States..

-

NatureServe. 2018 (Date accessed). NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://explorer.natureserve.org.. http://explorer.natureserve.org.

-

Swain, P.C. 2016. Classification of the natural communities of Massachusetts, Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife,.

-

USNVC [United States National Vegetation Classification]. 2017 (Date accessed). United States National Vegetation Classification Database V2.01. Federal Geographic Data Committee, Vegetation Subcomittee, Washington DC.

Other references

Cleland, D.T., J.A. Freeouf, J.E. Keys, G.J. Nowacki, C. Carpenter, and W.H. McNab. 2007. Ecological Subregions: Sections and Subsections of the Coterminous United States. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report WO-76. Washington, DC.

Comer, P., D. Faber-Langendoen, R. Evans, S. Gawler, C. Josse, G. Kittel, S. Menard, M. Pyne, M. Reid, K. Schulz, K., Snow, and J.Teague. 2003. Ecological Systems of the United States: A Working Classification of U.S. Terrestrial Systems. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia.

Cowardin, L.M. et. al. 1979. Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater habitats of the United States. FWS/OBS-79/31, U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, DC.

Edinger, G.J., Evans, D.J., Gebauer, S., Howard, T.G., Hunt, D.M., and A.M. Olivero, A.M. (eds.). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State, Second Edition: A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY.

FGDC [Federal Geographic Data Committee]. 2008. National Vegetation Classification Standard, Version 2. Federal Geographic Data Committee, Vegetation Subcommittee, Washington DC.

NatureServe 2018. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://explorer.natureserve.org. (Accessed: January 2019).

Sneddon, L. A., Zaremba, R. E., and M. Adams. 2010. Vegetation classification and mapping at Cape Cod National Seashore, Massachusetts. Natural Resources Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR--2010/147. National Park Service, Philadelphia, PA.

Swain, P.C. 2016. Classification of the Natural Communities of Massachusetts. Version 2.0. Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Westborough, MA.

United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006. Land Resource Regions and Major land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbook 296.

United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2015. National Soils Information System (NASIS).

USNVC [United States National Vegetation Classification]. 2017. United States National Vegetation Classification Database, V2.01. Federal Geographic Data Committee, Vegetation Subcommittee, Washington DC. http://usnvc.org/explore-classification/ (Accessed: 2018)

Contributors

Nels Barrett, Ph.D.

Joshua Hibit

Approval

Nels Barrett, 9/17/2024

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 05/23/2020 |

| Approved by | Nels Barrett |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.