Ecological site group R006XG430WA

Loamy, Prairie

Last updated: 09/21/2023

Accessed: 02/21/2026

Ecological site group description

Key Characteristics

None specified

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Physiography

Hierarchical Classification

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 6 – Cascade Mountains, East Slope

LRU – Common Resource Areas (CRA):

6.5 – Chiwaukum Hills and Lowlands

6.6 – Yakima Plateau and Slopes

6.7 – Grand Fir Mixed Forest

6.8 – Oak-Conifer Eastern Cascades-Columbia Foothills

Site Concept Narrative:

Diagnostics:

More than 80% of the landscape of MLRA 6 is forest. This site stands out because of a lack of trees.

Loamy, prairie is an upland ecological site on the prairie portion of MLRA 6 – the high Prairie in Klickitat County, and the Swauk Prairie in Kittitas County. This site is found on all aspects except north. The soils are silt loam over gravelly clay loam and deeper than 40 inches. Prairie soils are not hydric.

The High Prairie and the Swauk Prairie are grassland steppe and do not have sagebrush, nor bitterbrush, and no rabbitbrush. Bitterbrush may be found on adjoining ecological sites, however. Perennial bunchgrasses dominate the reference state. Cool-season bunchgrasses form two distinct layers. Bluebunch wheatgrass and Idaho fescue are co-dominant bunchgrass in the top grass layer, with Sandberg bluegrass the major grass of the lower grass layer. Native forbs fill the interspaces. At most shrubs are a very minor component.

Principle Vegetative Drivers:

The moderately deep to deep loam over clay loam soils and precipitation of 20-24 inches drive the vegetative expression of this productive site. Most species have unrestricted rooting and the precipitation ensures a longer growing season. Loamy Prairie has enough spring rains to provide plenty of moisture for Idaho fescue to assume a co-dominate role in the reference community.

Influencing Water Features:

A plant’s ability to grow on a site and overall plant production is determined by soil-water-plant relationships

1. Whether rain and melting snow runs off-site or infiltrates into the soil

2. Whether soil condition remain aerobic or become saturated and become anaerobic

3. Water drainage and how quickly the soil reaches wilting point

With adequate cover of live plants and litter, there are no restrictions on Loamy sites with water infiltrating into the soil. These sites are well drained and are saturated for only a short period.

Physiographic Features:

Most of MLRA 6 is in the Northern and Middle Cascade Mountains. This mountainous area consists of sharp alpine summits with some higher volcanic cones to the west, and lower lying foothills to the east. Strongly sloping mountains and U-shaped valleys are dominant in the north, with eroded basalt plateaus more typical in the south. The East Slope of the Cascades is a transitional area between the moist, rugged Cascade Mountains to the west and the drier, lower lying Columbia Basalt Plateau to the east. MLRA 6 has some of the landforms typical of both mountains and plateaus.

Physiographic Division: Pacific Mountains

Physiographic Province: Cascade-Sierra Mountains

Physiographic Sections: Northern Cascade and Middle Cascade Mountains

Landscapes: Mountains, hills and till plains

Landform: Side-slopes, benches and moraines

Elevation: Dominantly 1,100 to 3,000 feet

Central tendency: 1,800 to 2,500 feet

Slope: Total range: 0 to 60 percent

Central tendency: 2 to 30 percent

Aspect: Occurs on all aspects

Geology:

MLRA 6 consists of Pre-Cretaceous metamorphic rocks cut by younger igneous intrusives. Tilted blocks of marine shale, carbonate, and other sediments occur in the far north, and some younger continental, river-laid sediments occur around Leavenworth, WA. Columbia River basalt is dominant in the southern portion of the state. Alpine glaciation has left remnants of glacial till, debris, and outwash in the northern part of this MLRA.

Climate

The climate across MLRA 6 is characterized by moderately cold, wet winters, and hot, dry summers, with limited precipitation due to the rain shadow effect of the Cascades. The average annual precipitation for most of the East Slope of the Cascades is 16-50 inches. Seventy-five to eighty percent of the precipitation comes late October through March as a mixture of rain and snow. The lowest precipitation occurs along the eastern edge, then increasing with rising elevation to the west. Most of the rainfall occurs as low-intensity, Pacific frontal storms during the winter, spring and fall. Rain turns to snow at the higher elevations. All areas receive snow in winter. Summers are relatively dry. The East Slopes experience greater temperature extremes and receive less precipitation than the west side of the Cascades. The shortest freeze-free periods occur along the western edge and the northern end of this MLRA, which are mountainous. The longest freeze-free periods occur along the Columbia River Gorge.

Mean Annual Precipitation:

Range: 16-24 inches

Central tendency: 20-24 inches

Mean Annual Air Temperature:

Range: 46 to 54 degrees

Central tendency: 48 to 52 degrees

Soil moisture regime is xeric.

Frost-free Period (days):

Total range: 80 to 140

Central tendency: 100 to 130

The growing season for Prairie Loamy is March through mid-August.

Soil temperature regime is dominantly mesic.

Soil features

Edaphic:

Loamy, prairie ecological site commonly occurs with North aspect, prairie, Shallow stony, prairie and Very shallow ecological sites.

Representative Soil Features:

This ecological site components are dominantly Pachic and Ultic taxonomic subgroups of Palexerolls and Argixerolls great groups of the Mollisols. Soils are moderately deep or deeper. Average available water capacity of about 6.0 inches (15.2 cm) in the 0 to 40 inches (0-100 cm) depth range.

Soil parent material is dominantly mixed loess and glacial till in the upper part of the soil over residuum.

The associated soils are Swauk, Qualla, Hyprairie and similar soils.

Dominate soil surface is silt loam to loam.

Dominant particle-size class is fine loamy.

Fragments on surface horizon > 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 0

Fragments within surface horizon > 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 5

Average: 0

Fragments within surface horizon ≤ 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 10

Average: 5

Subsurface fragments > 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 10

Average: 2

Subsurface fragments ≤ 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 20

Average: 10

Drainage Class: Dominantly well drained

Water table depth: Dominantly greater than 60 inches

Flooding:

Frequency: None

Ponding:

Frequency: None

Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity Class:

0 to 10 inches: Moderately high and high

10 to 40 inches: Moderately high to low

Depth to root-restricting feature (inches):

Minimum: 30

Maximum: Greater than 60

Electrical Conductivity (dS/m):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 0

Sodium Absorption Ratio:

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 0

Calcium Carbonate Equivalent (percent):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 0

Soil Reaction (pH) (1:1 Water):

0 - 10 inches: 5.6 to 7.3

10 - 40 inches: 6.1 to 7.3

Available Water Capacity (inches, 0 – 40 inches depth):

Minimum: 4.1

Maximum: 8.1

Average: 6.0

Vegetation dynamics

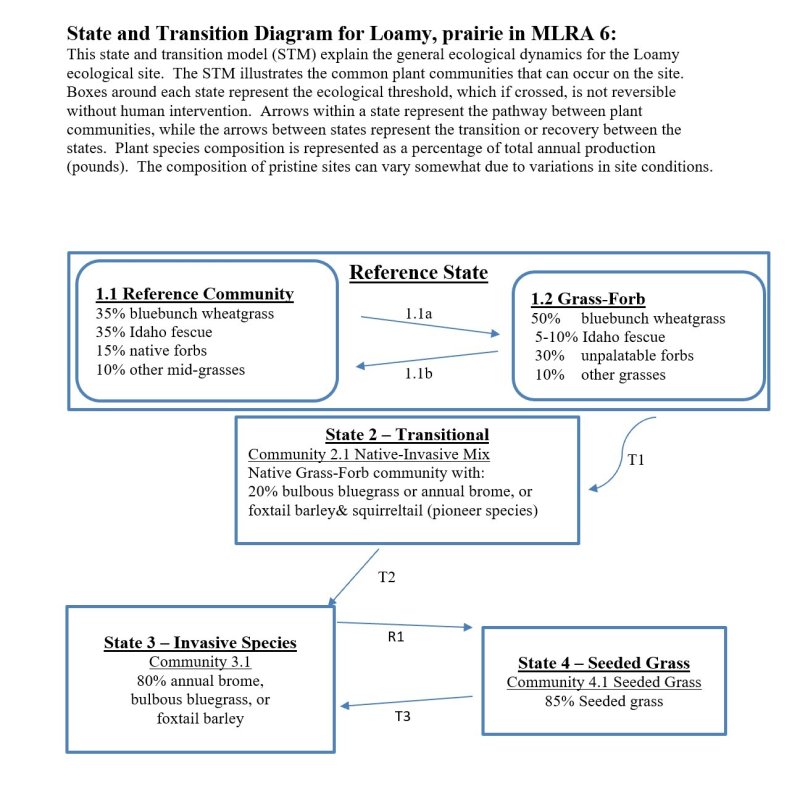

Ecological Dynamics:

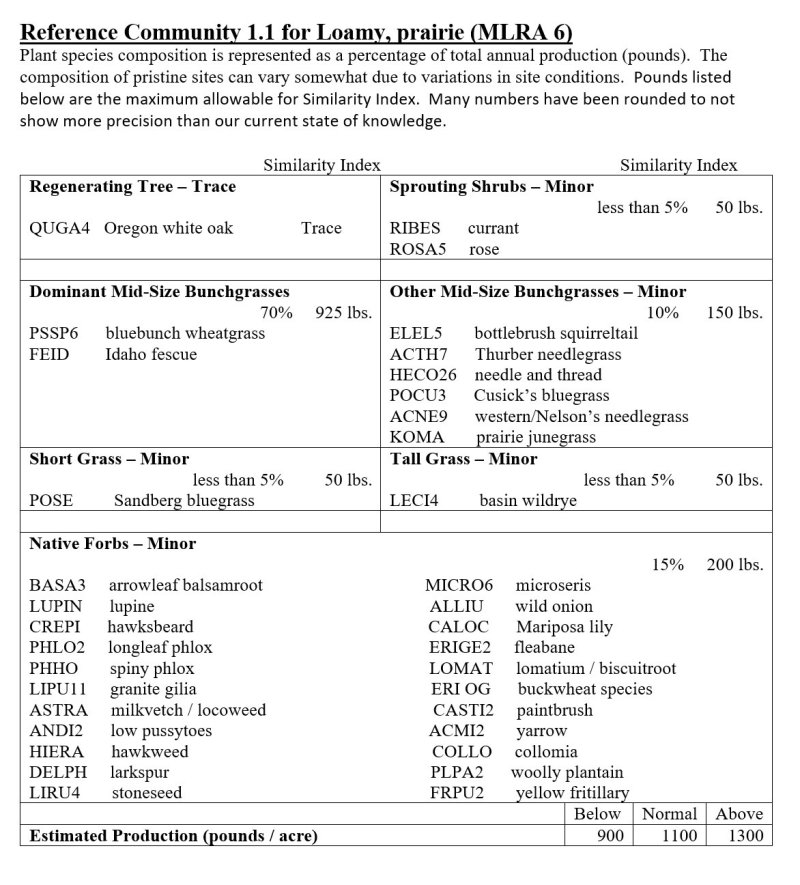

Loamy, prairie produces about 900-1300 pounds/acre of biomass annually.

In the reference condition bluebunch wheatgrass and Idaho fescue dominate the Loamy prairie ecological site. Both species are long-lived, mid-sized bunchgrasses. Idaho fescue is shorter and has a dense clump of shoots, while bluebunch wheatgrass is taller and is less dense. Bluebunch has an awned spike seed head while Idaho fescue has an awned panicle seed head. The ratio of Idaho fescue to bluebunch wheatgrass plants on any site can vary due to aspect and elevation.

Both grasses provide a crucial and extensive network of roots to the upper portions (up to 48” deep in soils with no root-restrictive horizons) of the soil profile. These roots create a massive underground source to stabilize the soils, provide organic matter and nutrients inputs, and help maintain soil pore space for water infiltration and water retention in the soil profile. The extensive rooting system of mid-sized bunchgrasses leave very little soil niche space available for invasion by other species. This drought resistant root can compete with, and suppress, the spread of exotic weeds.

The stability and resiliency of the reference communities is directly linked to the health and vigor of both bluebunch wheatgrass and Idaho fescue. Refer to pages 8-9 for more details about bluebunch physiology.

The natural disturbance regime for grassland communities is periodic lightning-caused fires. Ponderosa pine communities have the shortest FRI of about 10-20 years (Miller). The FRI increases as one moves to wetter forested sites or to dries shrub steppe

communities. Given the uncertainties and opinions of reviewers, a mean of 75 years was chosen for Wyoming sagebrush communities (Rapid Assessment Model). This would place the historic FRI for grassland steppe at 30-50 years perhaps, and even as short as 5-10 years in some locations.

The effect of fire on the community depends upon both the severity and season of the burn. See Vallentine’s Range Improvement for more detail. With a light to moderate fire there can be a mosaic of burned and unburned patches. The perennial grasses thrive as the fire does not get into the crown. With adequate soil moisture Idaho fescue, bluebunch wheatgrass and prairie junegrass can make tremendous growth the year after the fire. Largely, the community is not affected by lower intensity fire.

A severe fire puts stress on the entire community. Bluebunch wheatgrass, a fire-resilient grass, will have weak vigor for a few years but generally survives. Reduced vigor of bluebunch allows weeds to become established. Some spots and areas can be completely sterilized. Idaho fescue plants are very much at risk with a severe burn coupled with wind. Under windy conditions, a fire can burn into the crown of Idaho fescue, leaving behind “black holes” or nothing but ash where fescue plants were incinerated. Sterilized spots and dead Idaho fescue plants makes the site vulnerable to exotic invasive species, so seeding should be strongly considered. Bluebunch wheatgrass keeps the site resistant to change, while Idaho fescue makes the site more at risk.

Grazing is another common disturbance that occurs to this ecological site. Grazing pressure can be defined as heavy grazing intensity, or frequent grazing during reproductive growth, or season-long grazing (the same plants grazed more than once). As grazing pressure increases the plant community unravels in stages:

1. Idaho fescue declines while bluebunch wheatgrass and unpalatable forbs increase

2. All grasses decline while unpalatable forbs continue to increase. Invasive species such as bulbous bluegrass, annual bromes or ventenata colonize the site

3. The site can become an invasive grass community

As grazing progressively thins the native perennials, the alien species take their place, finally becoming dominant.

Managing grasslands to improve the vigor and health of native bunchgrasses begins with an understanding of grass physiology. New growth each year begins from basal buds. Bluebunch wheatgrass plants rely principally on tillering, rather than establishment of new plants through natural reseeding. During seed formation, the growing points become elevated and are vulnerable to damage or removal.

If defoliated during the formation of seeds, bluebunch wheatgrass has limited capacity to tiller compared with other, more grazing resistant grasses (Caldwell et al., 1981). Repeated critical period grazing (boot stage through seed formation) is especially damaging. Over several years each native bunchgrass pasture should be rested during the critical period two out of every three years (approximately April 15–July 15). And each pasture should be rested the entire growing-season every third year (approximately March 1 – July 15).

In the spring each year it is important to monitor and maintain an adequate top growth: (1) so plants have enough energy to replace basal buds annually, (2) to optimize regrowth following spring grazing, 3) to protect the elevated growing points of bluebunch wheatgrass, and (4) to avoid excessive defoliation of Idaho fescue with its weak stems.

Bluebunch wheatgrass and Idaho fescue remain competitive if:

(1) Basal buds are replaced annually,

(2) Enough top-growth is maintained for growth and protection of growing points,

(3) Idaho fescue makes viable seed and

(4) The timing of grazing and non-grazing is managed over a several-year period. Careful management of late spring grazing is especially critical

For more grazing management information refer to Range Technical Notes found in Section I Reference Lists of NRCS Field Office Technical Guide for Washington State.

In Washington, bluebunch wheatgrass communities provide habitat for a variety of upland wildlife species.

Supporting Information:

Associated Sites:

Loamy, prairie is associated with North Aspect, Shallow Stony and Very shallow ecological sites.

Similar Sites:

Loamy, prairie is similar to Loamy for the Goldendale Prairie in MLRA 8.

Inventory Data References (narrative):

Data to populate Reference Community came from several sources: (1) NRCS ecological sites from 2004, (2) Soil Conservation Service range sites from 1980s and 1990s, (3) Daubenmire’s habitat types, and (4) ecological systems from Natural Heritage Program

Major Land Resource Area

MLRA 006X

Cascade Mountains, Eastern Slope

Stage

Provisional

Contributors

Provisional Site Author: Kevin Guinn Technical Team: K. Bomberger K. Paup-Lefferts, R. Fleenor

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.