Ecological site group R008XG220WA

Stony Foothills, bitterbrush

Last updated: 09/22/2023

Accessed: 12/20/2025

Ecological site group description

Key Characteristics

None specified

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Physiography

Hierarchical Classification

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 8 – Columbia Plateau

LRU – Common Resource Areas (CRA):

8.1 - Channeled Scablands

8.2 - Loess Islands

8.3 - Okanogan Drift Hills

8.4 - Moist Pleistocene Lake Basins

8.5 - Moist Yakima Folds

8.7 - Okanogan Valley

Site Concept Narrative:

Diagnostics:

Stony foothills, bitterbrush is an upland shrub-steppe site occurring in the foothill areas below the lower tree-line of MLRA 6 (East Slope of Cascades). This site occurs on both flat and north facing slopes.

The soils are deep (60 inches or greater), coarse textured and rocky. Textures are mostly sandy loam and sand with some loams. Soils are often gravelly to very gravely to extremely stony. Soils are well drained.

Fire sensitive, bitterbrush dominates the reference state overstory, while perennial bunchgrasses such as Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass are dominant in the herbaceous understory. The shrub layer is typically waist- to shoulder-height bitterbrush with a mix of other shrub steppe species scattered throughout including Wyoming sagebrush, rabbitbrush, and current.

Bitterbrush areas in MLRA 8 are east of or adjacent to the Ponderosa pine forests including: Klickitat and Yakima counties, then from central Kittitas County northward to the Canadian border.

Principle Vegetative Drivers:

The coarse soils and neutral to north aspect drive the vegetative expression of this site. Bitterbrush prefers well drained, coarse soils, while the neutral or north slopes are good for both bluebunch and Idaho fescue.

Influencing Water Features:

A plant’s ability to grow on a site and overall plant production is determined by soil-water-plant relationships

1. Whether rain and melting snow runs off-site or infiltrates into the soil

2. Whether soil condition remain aerobic or become saturated and become anaerobic

3. Water drainage and how quickly the soil reaches wilting point

With adequate plant cover and litter, there water infiltrates into Stony foothills, bitterbrush readily. These sites are well drained and are saturated for only a short period.

Physiographic Features:

The landscape is part of the Columbia basalt plateau. Stony foothills, bitterbrush sites are most commonly found on benches, plateaus and hillslopes, but not on south slopes.

Physiographic Division: Intermontane Plateau

Physiographic Province: Columbia Plateau

Physiographic Sections: Walla Walla Plateau Section

Landscapes: Hills, valleys and plateaus

Landform: Sideslopes, terraces, benches, alluvial fans

Elevation: Dominantly 700 to 4,000 feet

Central tendency: 1,500 to 3,000 feet

Slope: Total range: 0 to 90 percent

Central tendency: 2 to 30 percent

Aspect: Occurs on all aspects except southernly slopes

Geology:

This MLRA is almost entirely underlain by Miocene basalt flows. Columbia River basalt is covered in many areas with as much as 200 feet of loess and volcanic ash. Small areas of sandstones, siltstones, and conglomerates of the Upper Tertiary Ellensburg Formation are along the western edge of this area. Some Quaternary glacial drift covers the northern edge of the basalt flows, and some Miocene-Pliocene continental sedimentary deposits occur south of the Columbia River, in Oregon.

A wide expanse of scablands in the eastern portion of this MLRA, in Washington, was deeply dissected about 16,000 years ago, when an ice dam that formed ancient glacial Lake Missoula was breached several times, creating catastrophic floods. The geology of the northernmost part of this MLRA is distinctly different from that of the rest of the area. Alluvium, glacial outwash, and glacial drift fill the valley floor of the Okanogan River and the side valleys of tributary streams. The fault parallel with the valley separates pre-Tertiary metamorphic rocks on the west, in the Cascades, from older, pre-Cretaceous metamorphic rocks on the east, in the Northern Rocky Mountains. Mesozoic and Paleozoic sedimentary rocks cover the metamorphic rocks for most of the length of the valley on the west.

Climate

The bitterbrush-Idaho fescue areas tend to be both cooler and wetter than Wyoming sagebrush-bluebunch wheatgrass areas (Daubenmire). Stony Foothills, which favors Idaho fescue, has a cooler micro-climate than the south facing Stony Foothills South slope. The climate is characterized by moderately cold, wet winters, and hot, dry summers, with limited precipitation due to the rain shadow effect of the Cascades. Taxonomic soil climate is either xeric (12 – 16 inches PPT) or aridic moisture regimes (10 – 12 inches PPT) with a mesic temperature regime.

Mean Annual Precipitation:

Range: 10 – 16 inches

Seventy to seventy-five percent of the precipitation comes late October through March as a mixture of rain and snow. June through early October is mostly dry.

Mean Annual Air Temperature:

Range: 45 to 52 F

Central Tendency: 47 – 50 F

Freezing temperatures generally occur from late-October through early-April. Temperature extremes are 0 degrees in winter and 110 degrees in summer. Winter fog is variable and often quite localized, as the fog settles on some areas but not others.

Frost-free Period (days):

Total range: 110 to 190

Central tendency: 120 to 160

The growing season for Stony foothills, bitterbrush is April through end of July.

Soil features

Edaphic:

The Stony foothills, bitterbrush ecological site occurs with Stony foothills south aspect bitterbrush, Cool Loamy, Stony, and Loamy ecological sites.

Representative Soil Features:

This ecological site components are dominantly Aridic, Ultic and Vitrandic taxonomic subgroups of Haploxerolls, Durixerolls and Argixerolls great groups of the Mollisols taxonomic orders. Soils are moderately deep to very deep. Average available water capacity of about 5.0 inches (12.7 cm) in the 0 to 40 inches (0-100 cm) depth range.

Soil parent material is dominantly mixed loess, colluvium and residuum with influence of volcanic ash possible.

The associated soils are Cashmont, Conconully, Haploxerolls, Sienna and similar soils.

Dominate soil surface is very stony silt loam to sandy loam, with ashy modifier sometimes occurring as well.

Dominant particle-size class is ashy to sandy-skeletal.

Fragments on surface horizon > 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 2

Fragments within surface horizon > 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 30

Average: 5

Fragments within surface horizon ≤ 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 30

Average: 15

Subsurface fragments > 3 inches (% Volume)

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 25

Average: 15

Subsurface fragments ≤ 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 40

Average: 10

Drainage Class: Dominantly well drained to excessively drained

Water table depth: Greater than 60 inches

Flooding:

Frequency: None

Ponding:

Frequency: None

Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity Class:

0 to 10 inches: High to moderately low

10 to 40 inches: Very high to moderately low

Depth to root-restricting feature (inches):

Minimum: 20

Maximum: Greater than 60 inches

Electrical Conductivity (dS/m)

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 2

Sodium Absorption Ratio

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 2

Calcium Carbonate Equivalent (percent):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 25

Soil Reaction (pH) (1:1 Water):

0 - 10 inches: 5.6 to 9.0

10 - 40 inches: 6.1 to 9.0

Available Water Capacity (inches, 0 – 40 inches depth)

Minimum: 1.3

Maximum: 9.7

Average: 5.0

Vegetation dynamics

Ecological Dynamics:

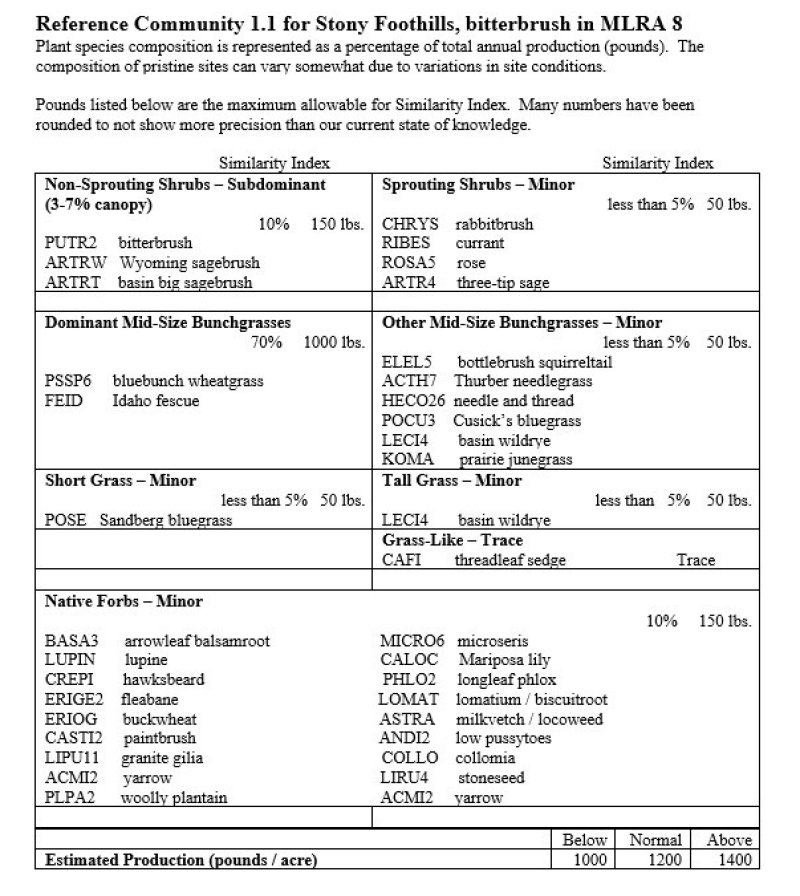

Stony foothills, bitterbrush produces about 1000-1400 pounds/acre of biomass annually.

Antelope bitterbrush, Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass are at the core of the Stony Foothills ecological site and warrant a degree of understanding.

Antelope bitterbrush is a very palatable, high quality shrub for big game and livestock. It is adapted to a wide range of soils and precipitation. Bitterbrush is usually 2-6 feet in height and up to 8 feet in width. Rodents normally cache bitterbrush seed within 50-75 feet of an existing seed source. Following a fire, the rodent seed caches become an important source of regeneration. Another important source of regeneration are pockets of unburned rangeland that provide much needed seed to the system.

Idaho fescue is shorter and has a dense clump of shoots, while bluebunch wheatgrass is taller and is less dense. Both species are long-lived bunchgrasses. Bluebunch has an awned or awnless seed head arranged in a spike while Idaho fescue has an awned seed head arranges in a panicle. The ratio of Idaho fescue to bluebunch wheatgrass plants on any site can vary due to aspect and elevation.

Both grasses provide a crucial and extensive network of roots to the upper portions (up to 48” deep in soils with no root-restrictive horizons) of the soil profile. These roots create a massive underground source to stabilize the soils, provide organic matter and nutrients inputs, and help maintain soil pore space for water infiltration and water retention in the soil profile. The extensive rooting system of mid-sized bunchgrasses leave very little soil niche space available for invasion by other species. This drought resistant root can compete with, and suppress, the spread of exotic weeds.

Needle and thread is another perennial bunchgrass on Stony Foothills. It produces erect, unbranched stems about 3 feet in height. The sharp-pointed seeds have a 4 to 5-inch long twisted awn. With wetting and drying needle and thread seed drills itself into the ground. Thus, needle and thread is one of the best seeders in the reference plant community. With grazing pressure on the dominant bunchgrasses, needle and thread increases.

The stability and resiliency of the reference communities is directly linked to the health and vigor of Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass. Research has found that the community remains resistant to medusahead if the site maintains at least 0.8 mid-sized bunchgrass plant/sq. ft. (Davies). These two bunchgrasses hold the system together. If we lose either or both bunchgrass the ecosystem begins to unravel.

The effect of fire on the main species is mixed for the Stony Foothills site. Bitterbrush is very susceptible to fire kill and is considered a weak sprouter. Bluebunch wheatgrass and needle and thread are fire tolerant, but Idaho fescue is much more sensitive to fire. Under windy conditions, a fire can burn into the crown of Idaho fescue, leaving behind “black holes” or nothing but ash. When a site loses its Idaho fescue, the holes will be filled by vigorous native species or exotic weeds. Bluebunch wheatgrass keeps the site resistant to change, while bitterbrush and Idaho fescue makes the site more at risk.

How one answers fire return intervals for bitterbrush communities depends on the frame of reference used. Currently conditions for Stony Foothills are communities often dominated by dense canopies of bitterbrush. These shrubs are 50-100 years old or older due to fire suppression. These bitterbrush plants do not readily re-sprout following fire. Germinating seeds, especially from rodent caches is the primary source to bitterbrush re-establishment. The framework of current conditions suggests a fire return interval of 50-100 years or longer.

Miller et al, paint a totally different picture for pre-settlement mountain big sage-bitterbrush-fescue communities. These communities were dominated by the herb layer. Shrubs were widely scattered and patchy. The fire regime was high frequency (10-20 years), low severity, low intensity. The landscape would have been a mosaic of burned and unburned patches. In any given fire some bitterbrush plants would have survived the fire. Also, bitterbrush plants were likely much younger (10-30 years old), more vigorous and more likely to sprout following fire. In recent years sprouting bitterbrush after low severity fire supports the notion of sprouting bitterbrush. Seedlings from rodent caches would have also been important for the recovery of the shrub layer.

A low intensity, high frequency fire regime favors bitterbrush sprouting and rapid tillering by both Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass. A high intensity, low frequency fire regime hinders recovery – Idaho fescue plants may be devastated, bluebunch wheatgrass set back, and bitterbrush regeneration limited to seedlings.

Fires with light severity will remove less bitterbrush and open smaller patches for grass and forb recovery, whereas the more severe fires will remove almost all the bitterbrush and leave vast areas open to return to bunchgrass dominance. This is how the patchy distribution occurs. So, fire resets the competitive advantage back to the bunchgrasses by removing much of the overstory. This, in turn, maintains the stability and overall resilience of the site. However, this is not always true as some fires are spotty or do not burn hot enough to fully remove the bitterbrush. Rabbitbrush and horsebrush are sprouting shrubs and may also increase following fire.

The longer the site goes without fire and the more grazing pressure added to the bunchgrasses, the more bitterbrush cover increases, and the more bunchgrasses decline. This leaves the dense bitterbrush community phase more vulnerable to outside pressures. Invasive species take advantage of the available soil rooting spaces in the interspaces. The once extensive grass roots are largely absent. Soils are no longer receiving the organic inputs, and there is less surface cover by grass litter. Both water infiltration into the soil, and water percolation through the soil, are affected, leaving open soil space that is drier and more vulnerable to wind and water erosion, and invasion by undesirable species. Once these undesirable species have colonized, the site is at high risk of crossing a threshold if a disturbance such as fire were to occur.

Grazing is another common disturbance that occurs to this ecological site. Grazing pressure can be defined as heavy grazing intensity, or frequent grazing during reproductive growth, or season-long grazing (same plants grazed more than once). As grazing pressure increases the plant community unravels in stages:

1. Cusick bluegrass is eliminated. Adjacent natives fill the void

2. Idaho fescue declines while bluebunch wheatgrass and threetip sage increase

3. Both Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass decline while threetip sage and threadleaf sedge increase

4. With further decline invasive species colonize the site

5. The site can become a shrub-annual grass community

Managing shrub steppe to improve the vigor and health of native bunchgrasses begins with an understanding of grass physiology. New growth each year begins from basal buds. Given the opportunity Idaho fescue readily produces new seedlings while bluebunch wheatgrass plants rely principally on tillering. During seed formation, the growing points of bluebunch wheatgrass become elevated and are vulnerable to damage or removal.

If defoliated during the formation of seeds, bluebunch wheatgrass has limited capacity to tiller compared with other, more grazing resistant grasses (Caldwell et al., 1981). Repeated critical period grazing is especially damaging. Over several years each native bunchgrass pasture should be rested during the critical period two out of every three years (approximately April 15 – July 15). And each pasture should be rested the entire growing-season every third year (approximately March 1 – July 15).

In the spring each year it is important to monitor and maintain an adequate top growth: (1) so plants have enough energy to replace basal buds annually, (2) to optimize regrowth following spring grazing, (3) to protect the elevated growing points of bluebunch wheatgrass, and (4) to avoid excessing defoliation of Idaho fescue with its weak stems.

Bluebunch wheatgrass and Idaho fescue remain competitive if:

(1) Basal buds are replaced annually,

(2) Enough top-growth is maintained for growth and protection of growing points, and

(3) The timing of grazing and non-grazing is managed over a several-year period. Careful management of late spring grazing is especially critical

For more grazing management information refer to Range Technical Notes found in Section I Reference Lists of NRCS Field Office Technical Guide for Washington State.

Antelope bitterbrush is an important browse species for big game animals and needs special management consideration with livestock in mind. There is no problem with spring grazing as livestock do not focus their attention to bitterbrush in the spring. Fall is a different story. Feeding some alfalfa every second or third day helps minimize livestock use of bitterbrush in the fall.

In Washington, antelope bitterbrush / Idaho fescue /bluebunch wheatgrass communities provide habitat for big game and sharp-tailed grouse.

Supporting Information:

Associated Sites:

Stony Foothills bitterbrush is associated with Stony Foothills South Aspect, Loamy, Stony and Very Shallow ecological sites in MLRA 8 Columbia Plateau, and also with Stony Foothills South Aspect in MLRA 6 East Slope of the Cascades.

Similar Sites:

Stony Foothills South Aspect in MLRA 8 and Stony Foothills South Aspect in MLRA 6 East Slope of the Cascades, and Stony Foothills in MLRA 9 Palouse Prairie are also bitterbrush sites.

Inventory Data References (narrative):

Data to populate Reference Community came from several sources: (1) NRCS ecological sites from 2004, (2) Soil Conservation Service range sites from 1980s and 1990s, (3) Daubenmire’s habitat types, and (4) ecological systems from Natural Heritage Program

Major Land Resource Area

MLRA 008X

Columbia Plateau

Subclasses

Stage

Provisional

Contributors

Provisional Site Author: Kevin Guinn

Technical Team: K. Moseley, G. Fults, R. Fleenor, W. Keller, C. Smith, K. Bomberger, C. Gaines, K. Paup-Lefferts

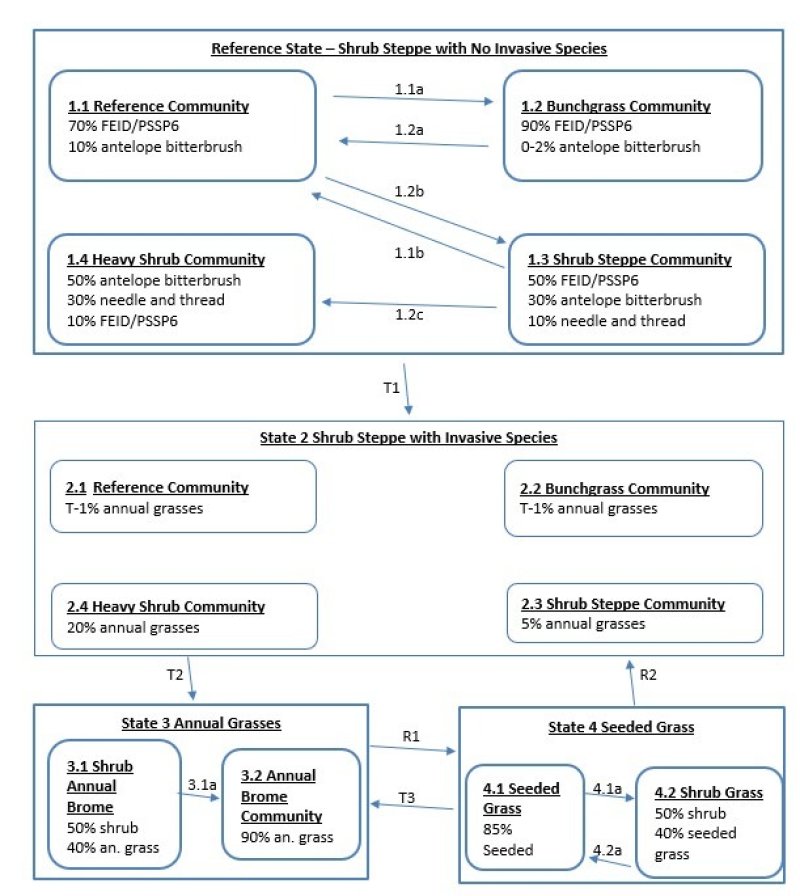

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.