Ecological dynamics

As ecological condition declines, Anderson's peachbrush, basin big sagebrush, Wyoming big sagebrush, and rubber rabbitbrush become more dominant. Species most likely to invade this site are annuals.

Fire Ecology:

The mean fire return interval on a dune ecological site is variable and is similar to adjacent ecological sites. Season of burning and environmental conditions impact antelope bitterbrush ability to survive fire and sprout. Antelope bitterbrush is very susceptible to fire kill. It is considered a weak sprouter and is often killed by summer or fall fire. Antelope bitterbrush in some areas may sprout after light-severity spring fire. High fuel consumptions increase antelope bitterbrush mortality and therefore favors seedling establishment. Wyoming big sagebrush establishes after fire from a seedbank; from seed produced by remnant plants that escaped fire; and from plants adjacent to the burn that seed in. Big sagebrush is readily killed when aboveground plant parts are charred by fire. If sagebrush foliage is exposed to temperature above 195 degrees Fahrenheit for longer than 30 seconds, the plant dies. Prolific seed production from nearby unburned plants coupled with high germination rates enables seedlings to establish rapidly following fire. Desert peach sprouts from rhizomes and/or lignotubers following fire, and is said to "reach its greatest development" on burned sites. Postfire seedling establishment is rare. Desert peach is typically only top-killed by fire. Neither aboveground stem survival nor complete shrub kill is reported following fire. Green ephedra generally sprouts vigorously from the roots or woody root crown after fire and rapidly produces aboveground biomass from surviving meristematic tissue. Fires in spiny hopsage sites generally occur in late summer when plants are dormant, and sprouting generally does not occur until the following spring. Spiny hopsage is considered to be somewhat fire tolerant and often survives fires that kill sagebrush. Mature spiny hopsage generally sprout after being burned. Spiny hopsage is reported to be least susceptible to fire during summer dormancy. Needleandthread grass is top-killed by fire. It may be killed if the aboveground stems are completely consumed. Needleandthread grass sprouts from the caudex following fire, if heat has not been sufficient to kill underground parts. Recovery usually takes 2 to 10 years. Indian ricegrass can be killed by fire, depending on severity and season of burn. Indian ricegrass reestablishes on burned sites through seed dispersed from adjacent unburned areas. Desert needlegrass has persistent dead leaf bases, which make it susceptible to burning. Fire removes the accumulation; a rapid, cool fire will not burn deep into the root crown. Most perennial grasses have root crowns that can survive wildfire. Basin wildrye is top-killed by fire. Older basin wildrye plants with large proportions of dead material within the perennial crown can be expected to show higher mortality due to fire than younger plants having little debris. Basin wildrye is generally tolerant of fire but may be damaged by early season fire combined with dry soil conditions.

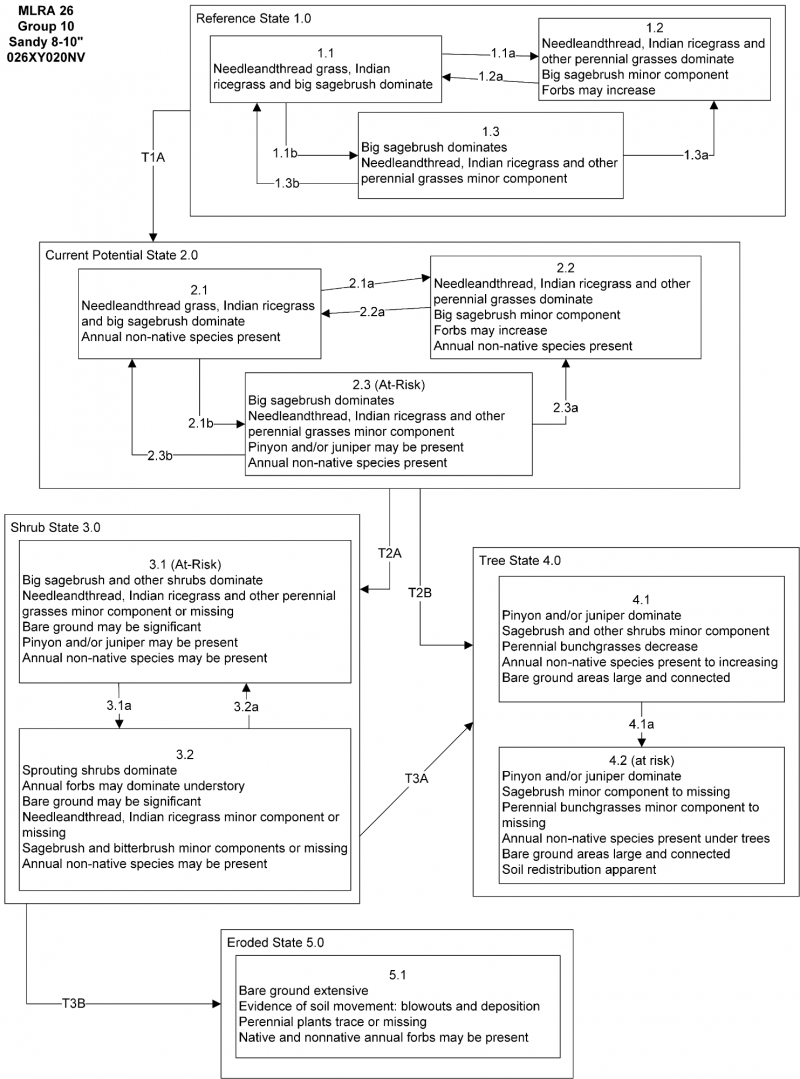

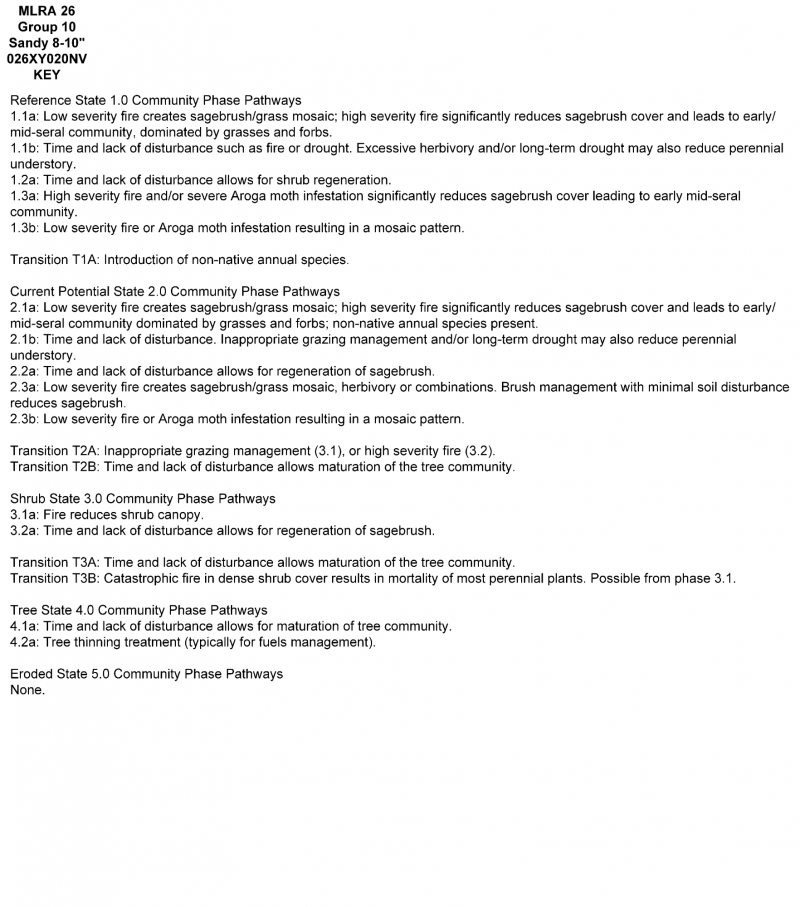

State and Transition Model Narrative Group 10

This is a text description of the states, phases, transitions, and community pathways possible in the State and Transition model for the MLRA 26 Disturbance Response Group 10. Other sites included in this group are: R026XY020NV, R026XY096NV, and R026XF005CA.

Reference State 1.0 Community Phase Pathways:

The Reference State 1.0 is a representation of the natural range of variability under pristine conditions. The reference state has three general community phases; a shrub-grass dominant phase, a perennial grass dominant phase and a shrub dominant phase. State dynamics are maintained by interactions between climatic patterns and disturbance regimes. Negative feedbacks enhance ecosystem resilience and contribute to the stability of the state. These include the presence of all structural and functional groups, low fine fuel loads, and retention of organic matter and nutrients. Plant community phase changes are primarily driven by fire, periodic drought, and/or insect or disease attack.

Community Phase 1.1:

This community is dominated by needle and thread grass, Indian ricegrass and big sagebrush. Fourwing saltbush, ephedra, and other shrubs are present. Desert needlegrass, basin wildrye, and a variety of perennial and annual forbs are also present in this phase.

Community Phase Pathway 1.1a, from phase 1.1 to 1.2:

Fire would decrease or eliminate the overstory of sagebrush and allow for the perennial bunchgrasses to dominate the site. Low severity fire creates sagebrush/grass mosaic. High severity fire significantly reduces sagebrush cover and leads to early/mid-seral community dominated by grasses and forbs. Release from drought may allow needle and thread and Indian ricegrass to increase in production.

Community Phase Pathway 1.1b, from phase 1.1 to 1.3:

Time and lack of disturbance such as fire or drought allows shrubs to become dominant. Excessive herbivory and/or long-term drought may also reduce perennial herbaceous understory.

Community Phase 1.2:

This community phase is characteristic of a post-disturbance, early seral community. Needle and thread, Indian ricegrass and other perennial grasses dominate. Big sagebrush is a minor component. Forbs and sprouting shrubs may increase.

Community Phase Pathway 1.2a, from phase 1.2 to 1.1:

Time and lack of disturbance allows sagebrush to reestablish.

Community Phase 1.3:

Big sagebrush increases in the absence of disturbance. Needle and thread, Indian ricegrass, and other perennial grasses may be a minor component.

Community Phase Pathway 1.3a, from phase 1.3 to 1.2:

Fire would decrease or eliminate the overstory of sagebrush and allow for the perennial bunchgrasses to dominate the site. Low severity fire creates sagebrush/grass mosaic. High severity fire significantly reduces sagebrush cover and leads to early/mid-seral community dominated by grasses and forbs. This pathway may also occur after a severe Aroga moth infestation that significantly reduces live sagebrush cover.

Community Phase Pathway 1.3b, from phase 1.3 to 1.1:

Aroga moth infestation reduces live sagebrush cover and allows grasses to increase in the understory. Release from drought may allow needle and thread and Indian ricegrass to increase in production.

T1A: Transition from Reference State 1.0 to Current Potential State 2.0:

Trigger: This transition is caused by the introduction of non-native annual weeds, such as cheatgrass, mustard (Descurainia or Sisymbrium spp.), and Russian thistle (Salsola tragus).

Slow variables: Over time the annual non-native plants will increase within the community, decreasing organic matter inputs from deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses. This leads to reductions in soil water holding capacity.

Threshold: Any amount of introduced non-native species causes an immediate reduction in the resilience of the site. Annual non-native species cannot be easily removed from the system and have the potential to significantly alter disturbance regimes from their historic range of variation.

Current Potential State 2.0 Community Phase Pathways:

This state is similar to the Reference State 1.0. Ecological function has not changed, however the resiliency of the state has been reduced by the presence of invasive weeds. This state has the same three general community phases as the Reference State. Negative feedbacks enhance ecosystem resilience and contribute to the stability of the state. These include the presence of all structural and functional groups, low fine fuel loads and retention of organic matter and nutrients. Positive feedbacks reduce ecosystem resilience and stability of the state. These include the non-natives’ high seed output, persistent seed bank, rapid growth rate, ability to cross pollinate, and adaptations for seed dispersal. Additionally, the presence of highly flammable annual non-native species reduces State resilience because these species can promote fire where historically fire has been infrequent. This leads to positive feedbacks that further the degradation of the system.

Community Phase 2.1:

This community is dominated by needle and thread grass, Indian ricegrass and big sagebrush. Fourwing saltbush, ephedra, and other shrubs are present. Desert needlegrass, basin wildrye, and a variety of perennial and annual forbs are also present in this phase. Annual non-native species present.

Community Phase Pathway 2.1a, from phase 2.1 to 2.2:

Fire would decrease or eliminate the overstory of sagebrush and allow for the perennial bunchgrasses to dominate the site. Low severity fire creates sagebrush/grass mosaic. High severity fire significantly reduces sagebrush cover and leads to early/mid-seral community dominated by grasses and forbs; non-native annual species present.

Community Phase Pathway 2.1b, from phase 2.1 to 2.3:

Time, long-term drought, grazing management that favors shrubs or combinations of these would allow the sagebrush overstory to increase and dominate the site, causing a reduction in the perennial bunchgrasses.

Community Phase 2.2:

This community phase is characteristic of a post-disturbance, early seral community. Needle and thread, Indian ricegrass and other perennial grasses dominate. Big sagebrush is a minor component. Forbs and sprouting shrubs may increase. Annual non-native species present.

Community Phase Pathway 2.2a, from phase 2.2 to 2.1:

Absence of disturbance over time allows for the sagebrush to recover. This may be combined with grazing management that favors shrubs.

Community Phase 2.3 (At-Risk):

Big sagebrush dominates and the perennial grasses become a minor component. Pinyon and juniper may be present. Annual non-native species present.

Community Phase Pathway 2.3a, from phase 2.3 to 2.2:

Fire would decrease or eliminate the overstory of sagebrush and allow for the perennial bunchgrasses to dominate the site. Low severity fire creates sagebrush/grass mosaic. High severity fire significantly reduces sagebrush cover and leads to early/mid-seral community dominated by grasses and forbs. This pathway may also occur after a severe Aroga moth infestation that significantly reduces live sagebrush cover. Brush treatments with minimal soil disturbance will also decrease sagebrush and release the perennial understory. Annual non-native species are present and may increase in the community.

Community Phase Pathway 2.3b, from phase 2.3 to 2.1:

A change in grazing management that reduces shrubs will allow the perennial bunchgrasses in the understory to dominate. Heavy late-fall or winter grazing may cause mechanical damage and subsequent death to sagebrush, facilitating an increase in the herbaceous understory. Brush treatments with minimal soil disturbance will also decrease sagebrush and release the perennial understory. A low severity fire would decrease the overstory of sagebrush or leave patches of shrubs, and would allow the understory perennial grasses to dominate. This pathway may also occur after a severe Aroga moth infestation that significantly reduces live sagebrush cover. Annual non-native species are present and may increase in the community.

T2A: Transition from Current Potential State 2.0 to Shrub State 3.0:

Trigger: Inappropriate, long-term grazing of perennial bunchgrasses during the growing season would favor shrubs and initiate transition to Community Phase 3.1. Fire would cause a transition to Community Phase 3.2.

Slow variables: Long term decrease in deep-rooted perennial grass density resulting in a decrease in organic matter inputs and subsequent soil water decline.

Threshold: Loss of deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses changes spatial and temporal nutrient cycling and nutrient redistribution, and reduces soil organic matter.

T2B: Transition from Current Potential State 2.0 to Tree State 4.0:

Trigger: Time and lack of disturbance or management action allows juniper and/or Pinion to dominate. This may be coupled with grazing management that favors tree establishment by reducing understory herbaceous competition for site resources Feedbacks and ecological processes: Trees increasingly dominate use of soil water, contributing to reductions in soil water availability to grasses and shrubs. Overtime, grasses and shrubs are outcompeted. Reduced herbaceous and shrub production slows soil organic matter inputs and increases soil erodibility through loss of cover and root structure.

Slow variables: Over time the abundance and size of trees will increase.

Threshold: Trees dominate ecological processes and number of shrub skeletons exceed number of live shrubs. Minimal recruitment of new shrub cohorts.

Shrub State 3.0 Community Phase Pathways:

This state has two community phases: a big sagebrush dominated phase and a sprouting shrub dominated phase. This state is a product of many years of heavy grazing during time periods harmful to perennial bunchgrasses. Shrubs dominate the plant community. If coming from phase 2.3, big sagebrush canopy cover is high and these plants may be decadent, reflecting stand maturity and lack of seedling establishment due to competition with mature plants. Typically, this state has little herbaceous understory and may be experiencing soil movement in the interspaces. The shrub overstory dominates site resources such that soil water, nutrient capture, nutrient cycling and soil organic matter are temporally and spatially redistributed.

Community Phase 3.1:

Big sagebrush and other shrubs dominate. Needle and thread, Indian ricegrass and other perennial grasses are only present in trace amounts, under shrubs, or may be missing entirely. Pinyon and/or juniper may be present. Annual non-native species may be present.

Community Phase Pathway 3.1a, from Phase 3.1 to 3.2:

Fire, heavy fall grazing that causes mechanical damage to shrubs, and/or brush treatments with minimal soil disturbance will greatly reduce the overstory shrubs to trace amounts and allow annual forbs and sprouting shrubs to dominate the site.

Community Phase 3.2:

Sprouting shrubs such as fourwing saltbush, spiny hopsage, ephedra, and desert peach dominate the site. Annual forbs may dominate the understory. Perennial grasses and sagebrush may be a minor component or missing entirely. Bitterbrush may be present. Bare ground may be significant. Annual non-native species may be present.

Community Phase Pathway 3.2a, from Phase 3.2 to 3.1:

Time and lack of disturbance allows the shrub component to recover. The establishment of sagebrush can take many years unless aided with restoration efforts.

T3A: Transition from Shrub State 3.0 to Tree State 4.0:

Trigger: Lack of fire allows trees to dominate site. This may be coupled with inappropriate grazing management that reduces fine fuels.

Slow variables: Increased establishment and cover of juniper trees, reduction in organic matter inputs.

Threshold: Trees overtop Wyoming big sagebrush and out-compete shrubs for water and sunlight. Shrub skeletons exceed live shrubs with minimal recruitment of new cohorts.

T3B: Transition from Shrub State 3.0 to Eroded State 5.0:

Trigger: High-intensity fire (from 3.1) kills all non-sprouting shrubs and many sprouting shrubs.

Slow variables: Increased dominance of sagebrush and/or bitterbrush creates extreme woody fuel conditions. Loss of the deep-rooted bunchgrass understory leaves few plants capable of regenerating post-fire, and eliminates the seed bank of these species.

Threshold: Changes in plant community composition and spatial variability of vegetation due to the loss of perennial bunchgrasses truncates energy capture and impacts nutrient cycling and distribution. Large, potentially decadent shrubs dominate the landscape with a closed canopy.

Tree State 4.0 Community Phase Pathway:

This state has two community phases that are characterized by the dominance of Utah juniper and/or singleleaf pinyon in the overstory. Wyoming big sagebrush and perennial bunchgrasses may still be present, but they are no longer controlling site resources. Soil moisture, soil nutrients, soil organic matter distribution and nutrient cycling have been spatially and temporally altered.

Community Phase 4.1:

Utah juniper and/or singleleaf pinyon dominate the overstory and site resources. Trees are actively growing with noticeable leader growth. Trace amounts of bunchgrasses may be found under tree canopies and in interspaces. Sagebrush is stressed and dying. Annual non-native species are present under tree canopies. Bare ground interspaces are large and connected.

Community Phase Pathway 4.1a, from phase 4.1 to 4.2:

Time and lack of disturbance or management action allows Utah juniper and/or singleleaf pinyon to mature further and dominate site resources.

Community Phase 4.2:

Utah juniper and/or singleleaf pinyon dominate the site and tree leader growth is minimal. Annual non-native species may be the dominant understory species and will typically be found under the tree canopies. Trace amounts of sagebrush may be present, however, dead shrub skeletons will be more numerous than live sagebrush. Bunchgrasses may or may not be present. Needle and thread or mat forming forbs may be present in trace amounts. Bare ground interspaces are large and connected. Soil redistribution is evident.

Eroded State 5.0:

This state has one community phase. Abiotic factors including soil redistribution, erosion, and soil temperature are primary drivers of ecological condition within this state. Soil moisture, soil nutrients, and soil organic matter distribution and cycling are severely altered due to degraded soil surface conditions. Soil movement inhibits the germination of new seedlings. Regeneration of shrubs is not evident.

Community Phase 5.1:

Vegetation is sparse and bare ground dominates the visual aspect. Plants that tolerate soil movement and may remain, including Indian ricegrass, needle and thread, desert peach, and annual forbs. Russian thistle may be present. Soil deposition is apparent at the bases of plants and may form small dunes. Skeletons of burned shrubs may be present.

State 1

Reference Plant Community

Community 1.1

Reference Plant Community

The reference plant community is dominated by antelope bitterbrush, Anderson's peachbrush, needleandthread, and Indian ricegrass. Potential vegetative composition is about 45% grasses, 5% forbs and 50% shrubs. Approximate ground cover (basal and crown) is 20 to 30 percent.

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type |

Low

(lb/acre) |

Representative value

(lb/acre) |

High

(lb/acre) |

| Shrub/Vine |

250 |

350 |

400 |

| Grass/Grasslike |

225 |

320 |

365 |

| Forb |

25 |

30 |

35 |

| Total |

500 |

700 |

800 |