Ecological dynamics

MLRA 34B occurs in the lower elevation valleys of the northeastern part of the Colorado Plateau. The Colorado Plateau is a physiographic province located throughout eastern Utah, western Colorado, western New Mexico, and northern Arizona. It is characterized by uplifted plateaus, canyons, and eroded features. It lies south of the Uintah Mountains, north of the Mogollon transition area, west of the Rocky Mountains, and east of the central Utah highlands. The higher elevation portion of the Colorado Plateau, which is represented by MLRA 34B, is characterized by broken topography, large flat valleys, and a lack of perennial water sources. This area has a long history of human use (thousands of years). Archaeological evidence in nearby pinyon-juniper woodlands indicates areas modified by prehistoric humans and areas left pristine until European settlement (Cartledge and Propper, 1993). This area was also subjected to natural influences of herbivory, fire, and climate. Due to the broken topography, it rarely was used as habitat for large herds of native herbivores and rarely had large, frequent fires. This site is extremely variable; plant community composition varies with water fluctuations.

The precipitation pattern on this part of the Colorado Plateau is winter-summer bimodal. This means that this site developed under climatic conditions of wet, cold winters and hot, dry summers with summer monsoonal rains. This area has climatic fluctuations, and prolonged droughts are common; as it is located on the most northern end of the monsoonal rain belt. Between a year with above-average precipitation and a drought year, forbs are the most dynamic (Passey et al., 1982) and can vary up to fourfold. The precipitation and climate of MLRA 34B are conducive to producing pinyon/juniper and sagebrush complexes with high productive sites in the bottoms of the canyons. Predominant species on the Colorado Plateau are Wyoming big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata var. wyomingensis), mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata var. vaseyana), black sagebrush (Artemisia nova), basin big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata var. tridentata), Utah juniper (Juniperus utahensis), and pinyon (Pinus edulis).

This plant community evolved where drought is common and can be quite severe. The growing season usually starts in early to late March on this site. A study of shadscale’s ecology in western Colorado showed that shadscale begins vegetative growth in early to mid-March and blooms in late March to mid-April. Late bloom occurs from mid-April to early May. Fruiting generally occurs in early May to mid-June with seed ripening in mid-June to early July (Simonin, 2001). Shadscale establishment is from seed. Salt-desert communities have historically served as winter grazing areas for cattle and sheep. According to oral communications with early settlers, livestock was first brought into the Grand Valley between 1880 and 1890. At that time the area had thousands of cattle imported into it (Lusby, 1979). In addition, starting around 1915, large bands of sheep were moved across the valley on the way from winter range in Utah and the Grand Valley to summer range in the Colorado Mountains (Lusby, 1979). Heavy unrestricted grazing occurred during European settlement until 1934, when the Taylor Grazing Act was passed.

The most common disturbances on this site are high amounts of off-highway vehicle use, improper livestock grazing, drought, and erosion. The weather plays a large role in the disturbance regime in the salt desert. During droughty periods, perennial grasses decrease; during periods of normal and above-average precipitation, perennial grasses increase. Plant production on this site fluctuates with the amount of precipitation. The timing of the precipitation influences which annuals will be present on the site and their production. The common annual invaders on this site include cheatgrass, Halogeton, stork’s bill, and annual mustards. As site conditions deteriorate from disturbance, native perennial vegetation decreases and annual invasive species can establish. Seedings for salt-desert shrub communities in the western U.S. have not been very effective (Wien and West, 1971). Seedling emergence and early establishment depend on the precipitation. Droughts, which are common in these areas, can cause seeding to fail. As a result, complete removal of annual invasives, once established, may not be possible; suppression is more likely.

Fire occurrence in this system is dependent on the fuel load and plant moisture content. Shadscale-dominant salt-desert shrub communities with native range grasses produced relatively low amounts of fine fuels. This lack of continuous fuels to carry fires made fire rare to nonexistent in shadscale communities (Simonin, 2001). Thus, Semidesert Stony Loam (Shadscale) likely evolved with very low fire frequency. Shadscale is fire intolerant and does not readily recover from fire. The slow post-fire recovery of shadscale allows for easy invasion and subsequent replacement by cheatgrass in western rangelands (Simonin, 2001). Introduction of annual invasive grasses has greatly altered fire regimes where shadscale is a major vegetative component. These annuals increase fire frequency under wet to near-normal summer moisture conditions (Simonin, 2001). Heavy winter and spring rains can generate fuels by producing abundant stands of annual forbs and grasses. Fine fuels generated by annual grasses are long lived because grass biomass decomposes slowly under the continually low atmospheric moisture conditions inherent to the arid regions. In general, wet years followed by dry years increase the probability of fire, with large fires most likely in July or August. Fuel loads for shadscale/black greasewood have been measured at 250 to 750 pounds per acre (Simonin, 2001).

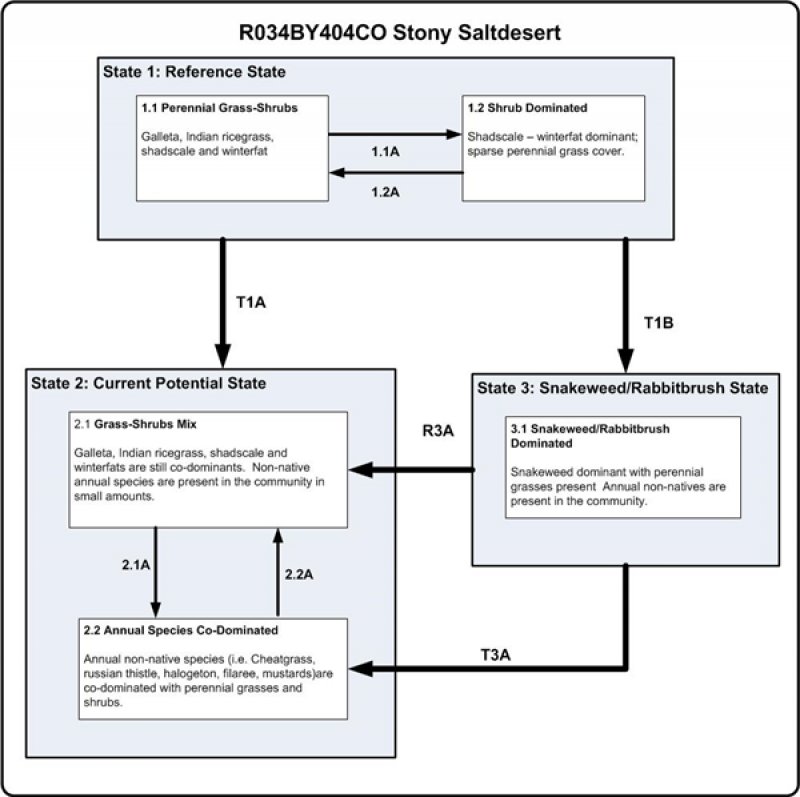

Variability in climate, soils, aspect, and complex biological processes cause the plant communities to differ. Factors contributing to annual production variability include wildlife use, drought, and insects. Factors contributing to species variability include soil texture, soil depth, rock fragments, slope, aspect, and micro-topography. The species lists are representative and do not include all occurring or potentially occurring species on this site. The lists are not intended to cover the full range of conditions, species, and responses of the site. The state-and-transition model depicted for this site is based on available research, field observations, and interpretations by experts and could change as knowledge increases. As more data is collected, some of these plant communities may be revised or removed and new ones may be added. The following diagram does not necessarily depict all the transitions and states that this site may exhibit, but it does show some of the most common plant communities.

State 1

Reference State

This state represents the natural ecological dynamics of the Semidesert Stony Loam (Shadscale) site. There are two dominant plant community phases in the Reference State. Drought, native herbivory, and fire are natural disturbances that change the pathways between community phases. Simonin (2001) states that the successional timeline of a shadscale community is generally slow in areas that have been grazed as well as those that have not been grazed. The state is dominated by warm-season perennial grasses (galleta) and shadscale. This plant community evolved in areas where drought is common and can be quite severe. Winterfat is a subdominant species on this site. It can become dominant if fire just scorches it tops and shadscale must regrow from seed (West, 1992). Which annual forbs occur and their production depend greatly on the season’s moisture and timing. The surface gravel, cobbles, and stones weathered from basalt help to armor the soil against erosion.

Community 1.1

Perennial Grasses - Shrub

Figure 8. Community Phase 1.1 in early summer during a wet year

Figure 9. Close up of site in Community Phase 1.1

Figure 10. Community Phase 1.1 during a wet year

Figure 11. Close up of site in Community Phase 1.1

Figure 12. Community Phase 1.1 in early spring

With only about 30 percent of the annual production of native vegetation from shrubs, this site has a grassland-shrub aspect. Galleta is the dominant grass. Another dominant native grass is Indian ricegrass. Shadscale and winterfat are the dominant shrubs. Globemallow and cleftleaf wild heliotrope are the dominant forbs. Trees do not grow naturally on this site. Bare ground makes up approximately 40 to 50 percent of the surface on average. Biological crusts, when present, cover approximately 5 percent of the surface and are characterized by light cyanobacteria in the interspaces with moss in some places. Surface rock fragments (30 to 40 percent) can be very prevalent and are characterized by gravel, cobbles, and stones weathered from basalt.

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type |

Low

(lb/acre) |

Representative value

(lb/acre) |

High

(lb/acre) |

| Grass/Grasslike |

225 |

325 |

425 |

| Shrub/Vine |

110 |

175 |

250 |

| Forb |

65 |

100 |

125 |

| Total |

400 |

600 |

800 |

Table 6. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover |

0%

|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover |

10-25%

|

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover |

15-30%

|

| Forb foliar cover |

1-5%

|

| Non-vascular plants |

0%

|

| Biological crusts |

1-10%

|

| Litter |

25-35%

|

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" |

20-35%

|

| Surface fragments >3" |

5-15%

|

| Bedrock |

0%

|

| Water |

0%

|

| Bare ground |

40-60%

|

Table 7. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (ft) |

Tree |

Shrub/Vine |

Grass/

Grasslike |

Forb |

| <0.5 |

– |

5-15% |

10-30% |

1-5% |

| >0.5 <= 1 |

– |

15-25% |

5-25% |

0-3% |

| >1 <= 2 |

– |

0-2% |

1-15% |

0-2% |

| >2 <= 4.5 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >4.5 <= 13 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >13 <= 40 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >40 <= 80 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >80 <= 120 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >120 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 1.2

Shrub Dominated

Figure 15. Shrub Dominated Phase

Figure 16. Shrub Dominated Phase in foreground

This community is characterized by shadscale and winterfat with little to no perennial forbs or grasses. The sparsely occurring perennial grasses are dominated by galleta. Forb production varies from year to year and fluctuates with climatic conditions. Bare ground makes up approximately 50 to 60 percent of the surface on average. Biological crusts (when present) cover approximately 5 to 10 percent of the surface and are characterized by light cyanobacteria in the interspaces with moss in some places. Surface rock fragments (30 to 40 percent) can be very prevalent and are characterized by gravel, cobbles, and stones weathered from basalt.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

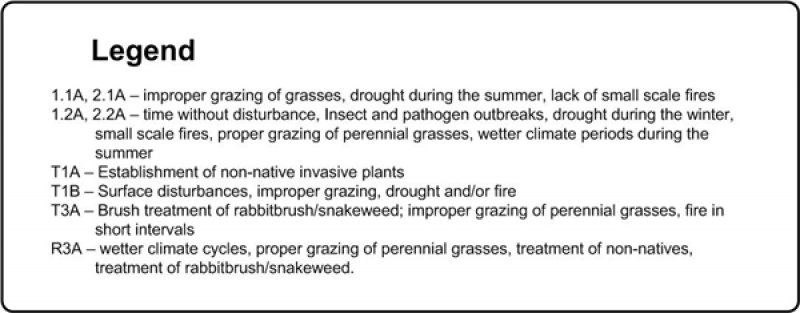

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Perennial Grasses - Shrub

This phase is characterized by loss of perennial grasses and forbs. One or more of the following drivers may cause this pathway: improper grazing of the perennial grasses, lack of small-scale fires, periods without disturbance, and prolonged drought especially during the spring and summer. The drivers in this pathway reduce the vigor of native perennial plants.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Perennial Grasses - Shrub

This pathway’s drivers consist of one or more of the following: proper grazing of perennial grasses, prolonged winter and fall drought (which decreases the amount of shrubs), wetter periods during the summer when grasses are actively growing, or small-scale fires.

State 2

Current Potential State

This state functions very similar to State 1. The main difference is how the plant community reacts once non-native annual invasive species are established in the understory. The most common annuals are cheatgrass and Halogeton. The primary disturbance mechanism is weather fluctuation. However, livestock grazing may influence the ecological dynamics of the site. The current potential state has less ability to resist change and less resilience following disturbances.

Community 2.1

Grass – Shrub Mix

Figure 18. Annual invasives mixed with native plants in Community Phase 2.1

Figure 19. Landscape with cheatgrass in Community Phase 2.1

Figure 20. Close up of annuals and native plants in Community Phase 2.1

Figure 21. Close up of site in Community Phase 2.1

This site is typically dominated by shadscale and galleta but annual invasive species are now present. Dominant annuals are cheatgrass and Halogeton. Other perennial or invasive grasses, shrubs, and forbs may also be present, and cover is variable. This community is at risk if it receives enough moisture for the annual weeds to flourish. The risk of fire is now greater and can occur when there is sufficient fine fuels to carry it. Fire converts this site into one dominated by cheatgrass and non-native annual forbs.

Community 2.2

Annual Species Co-Dominated

Figure 22. Transect view of Community Phase 2.2

Figure 23. Close up of site in Community Phase 2.2

This state is dominated by invasive species, of which cheatgrass and Halogeton are the most common. Other common annual weeds include Russian thistle, annual mustards, stork’s bill, and annual kochia (summer cypress). Native annual chenopods may increase significantly from trace amounts as the ecological condition deteriorates. Grasses decline drastically under continued deterioration and may nearly disappear. Shadscale or winterfat may or may not be present. The primary disturbance mechanisms are fire, improper livestock grazing, and drought. One or more invasive species have increased to the point where they influence or drive the disturbance regime and nutrient cycle. Research has shown that plant species differ substantially in their effects on soil water content and temperature and on the frequency and intensity of disturbance. After invasive plants have established, a site’s fundamental nutrient cycling processes, root pores, mycorrhizal associations, microbial species, and soil organic material change (Belnap and Phillips, 2001). These alterations can eventually create ecologically impoverished sites that are very difficult to restore to functionally diverse perennial herbaceous and woody communities. The competitiveness of the annual forbs and grasses, and the ability of these species to quickly establish after a disturbance, make this state extremely resistant to change and resilient after a disturbance.

Periods without disturbance may enable some native vegetation to re-establish. Natural fluctuations in weather and fire (if fine fuel accumulation is adequate) allow for the continued dominance of invasive plant species.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Annual Species Co-Dominated

This phase is characterized by loss of perennial grasses and forbs. One or more of the following drivers may cause this pathway: improper livestock grazing, heavy browsing by wildlife, prolonged drought, surface disturbances, and fire. The disturbances reduce the site’s vigor. Fire can be more of a driver in this pathway than others on this site.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Annual Species Co-Dominated

Periods without disturbance combined with normal and above-normal precipitation and proper livestock grazing may enable some native vegetation to re-establish. Once invasive species are present in the plant community, suppressing the annuals will be difficult and could require intensive management. This return pathway requires a long-term commitment.

State 3

Snakeweed/Rabbitbrush State

This state is caused by surface disturbance, such as by mining and development of roads and utility and pipeline corridors. It is dominated by broom snakeweed and yellow rabbitbrush, with reduced occurrence of shadscale and winterfat from the Reference State (1). The dominant grass is still galleta. Dominant forbs are globemallow and cleftleaf wild heliotrope. Periods without disturbance may enable limited native vegetation to re-establish. Drought, improper livestock grazing, or continued surface disturbances favor the continued dominance of broom snakeweed and yellow rabbitbrush. Because of the competitiveness of broom snakeweed and its ability to quickly establish after a disturbance, this state is extremely resistant to change.

Community 3.1

Snakeweed/Rabbitbrush Dominated

Figure 25. Site dominated by snakeweed in State 3

Figure 26. Site dominated by snakeweed in State 3

This plant community phase is characterized by a dominance of broom snakeweed and yellow rabbitbrush, where native grasses, shrubs, and forbs may also be present. Bare ground makes up approximately 40 to 60 percent of the surface on average. Biological crusts (when present) cover approximately 5 to 10 percent of the surface and are characterized by light cyanobacteria in the interspaces with moss in some places. Surface rock fragments (30 to 50 percent) can be very prevalent and are characterized by gravel, cobbles, and stones weathered from basalt.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

This transition occurs when the non-native invasive species become established on the site. Pathways to drive this transition can include one or more of the following: brush treatments, improper livestock grazing, wildlife browsing, prolonged drought, fire, if enough fine fuels, and surface disturbances such as off-road vehicle use, and road and pipeline development.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

This transition occurs when broom snakeweed and rabbitbrush increase in dominance. Pathway drivers typically include mechanical disturbances such as mining, pipeline development or other large surface disturbance, and improper grazing. Natural pathways are drought and fire.

Transition T3A

State 2 to 3

Pathway drivers include one or more of the following: brush treatments, improper grazing of perennial grasses, fire in shorter intervals, and continued surface disturbances. The main driver on this pathway is surface disturbance. This would transition to plant community 2.2.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 2

Adequate and above-normal precipitation at the right time, combined with proper grazing of perennial grasses, enables native vegetation to re-establish. Treatment of non-natives and rabbitbrush/snakeweed may be required. This would transition it to Plant Community 2.1.