Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R042AC247TX

Igneous Hill and Mountain, Desert Grassland

Accessed: 02/08/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

Similar sites

| R042AC249TX |

Limestone Hill and Mountain, Desert Grassland The Igneous Hill and Mountain Desert Grassland Desert Grassland site is similar to the Limestone Hill and Mountain Desert Grassland, but is formed from igneous (volcanic) parent material instead of limestone parent material. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

Not specified |

Physiographic features

The site occurs on rolling to very steep hills and mountains. Slopes range from 5 to 60 percent and elevation ranges from 3,500 to 4,500 feet.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hill

(2) Mountain (3) Ridge |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 1,067 – 1,372 m |

| Slope | 5 – 60% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The average annual precipitation usually ranges from 11 to 13 inches but extreme variations may range from 3 to 32 inches. There is a gradual decrease in precipitation from north to south in the area. Approximately 75 percent of the precipitation occurs as thunderstorms of short duration and high intensity during the months of June through October. Rainfall distribution is variable and a general rain during these months is uncommon. Rainfall is approximately 25 percent below average four years out of every ten years.

The optimum growing season usually ranges from July 1 through September, but is governed by time and amount of rainfall. Although frost-free days begin in April, sufficient moisture for growing plants to reach maturity is usually not available until late summer or early fall.

Frost-free period is approximately 224 days in the northern part of the zone, extending from about April 1 to November 1, and about 234 days in the southern part, extending from about March 21 to November 10.

High winds are common from March to mid-April. Daytime temperatures exceeding 100 degree F. are common from May through July.

Annual evaporation is about 100 inches.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 232 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 255 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 356 mm |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Influencing water features

None.

Soil features

Soils range from very shallow to shallow over igneous bedrock. Permeability is moderately slow and the soils are well drained. Runoff is medium on 5 to 20 percent slopes, and high on slopes greater than 20 percent. The regolith consists of a thin mantle of loamy earth, containing many coarse fragments. Underlying rocks are fine grained igneous rocks. Rock outcrops are common on slopes of more than 20 percent.

Soil mapunit components include Pantak, Scotal, Sauceda, Decoty, Holguin, Lingua, Reduff, Horsetrap, Bofecillos, Ohtwo, and Lampshire.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

rhyolite

(2) Colluvium – trachyte |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Very gravelly loam (2) Extremely gravelly clay loam (3) Very cobbly |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Slow |

| Soil depth | 10 – 51 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 26 – 46% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 29 – 36% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 10.16 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 15% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

6.1 – 7.8 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

20 – 50% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

10 – 30% |

Ecological dynamics

The Historic Climax Plant Community (HCPC) on the Igneous Hill and Mountain (Desert Grassland) site consists of bunch and stoloniferous grasses along with a variety of perennial forbs and woody shrubs.

Probably the factor that most influenced the historic vegetative composition of the site was extended dry weather. High rainfall events did occur but were episodic. However, insects and grazers such as rodents, deer, and infrequent fire certainly played a part. Bison were not documented in the historical record as being present in any significant amount. A lack of water was probably a contributing factor. The perennial grasses dominating the site could survive the periodic droughts as long as the density of woody plants did not become excessive, and top-removal of the grass plants did not occur too frequently. Overgrazing amplifies the effects of drought.

Early historical records do not always provide information specific to a site but can provide insight as to conditions existing in a general vicinity. Accounts suggest cattle, sheep, and horses were introduced into the southwest from Mexico in the mid-1500's. However, extensive ranching did not begin in the Trans-Pecos region until the 1880s. Early explorers described the vegetation as they traveled over parts of the Trans-Pecos. For instance, Captain John Pope in 1854 described a portion of the Trans-Pecos area as “…destitute of wood and water, except at particular points, but covered with a luxuriant growth of the richest and most nutritious grasses known to this continent…”. Other early travelers describe the scattered springs and water sources that were found in the region. Wagon travel could only be accomplished, along trails that had both water and forage sufficient for overnight stops. Livestock numbers peaked in the late 1880’s following the arrival of railroads. Some historical accounts document ranches with stocking rates as high as one animal unit per four acres; however, this was far from sustainable in this environment.

Decades of overgrazing with loss of vegetation and erosion make it a slow process to return to the HCPC community. In 1944 the southernmost portion of the Trans-Pecos area was set aside as Big Bend National Park. Grazing activities with livestock ceased. For example, in 1944, most of the Igneous Hill and Mountain Desert Grassland sites accessible to livestock were probably degraded and dominated by woody shrubs. After 60 years of no grazing, the majority of sites have not recovered to the historic plant community which provides insight into the length of time it takes for recovery in this environment.

The large livestock herds brought in during the favorable years, mainly sheep, could not be sustained during the drought. Overgrazing became a major issue as the extended dry weather was a harsh taskmaster to the early stock growers.

Cattle use on rangeland declines significantly on slopes steeper than 15 percent, however cattle numbers were never very large. Sheep and goats are however able to utilize slopes up to about 45 percent and can negotiate the surface rock cover better than cattle. It should be noted that abusive grazing by different kinds and classes of livestock will result in different impacts on the site. One effect of the removal of vegetated cover was to expose bare ground to erosion. Another effect was the deterioration of perennial grasses which removed the source of fine fuel to sustain periodic fires. More than likely, fires were not very frequent and when they did occur, the burn pattern was a mosaic governed by terrain and vegetative features.

Lehmann’s lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana) can occur throughout the, Desert Grassland and Mixed Prairie Land Resource Units. This non-native species has the potential to displace native species.

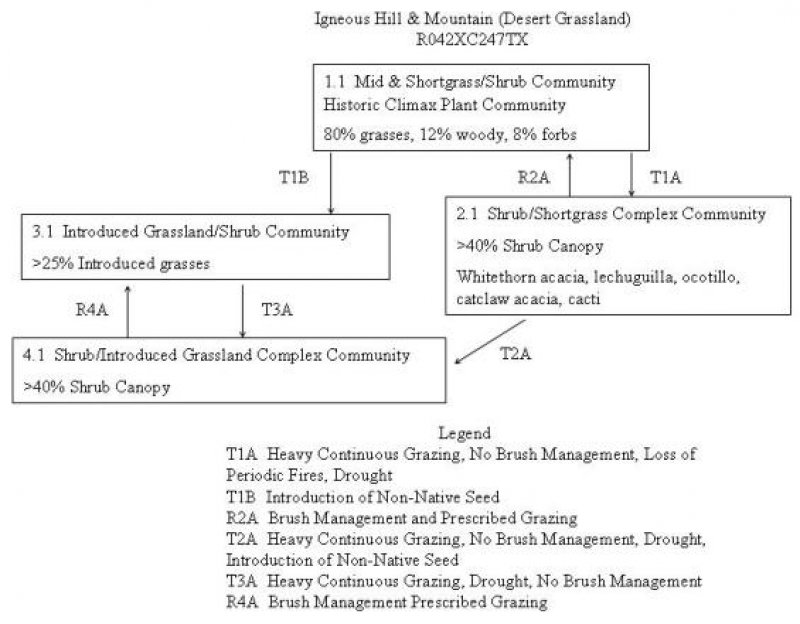

The following diagram suggests general pathways that the vegetation on this site might follow. There may be other states not shown on the diagram. This information is intended to show what might happen in a given set of circumstances; it does not mean that this would happen the same way in every instance. Local professional guidance should always be sought before pursuing a treatment scenario.

State and transition model

Figure 4. MLRA 42 - Igneous Hill & Mtn - DG - State & Transi

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Mid & Shortgrass/Shrub State

Community 1.1

Mid & Shortgrass/Shrub Community

Figure 5. 1.1 Mid & Shortgrass/Shrub Community

The HCPC on the Igneous Hill & Mountain Desert Grassland site consists of bunch and stoloniferous grasses along with a variety of perennial forbs and woody shrubs. This is the reference plant community. The HCPC, also known as the Mid & Shortgrass/Shrub Community (1), contains about 80% grasses, including 20% black grama (Bouteloua eriopoda), 15% sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), and 10% cane bluestem (Bothriochloa barbinodis), and tanglehead (Heteropogon contortus). Trace amounts of various sedges are present in the HCPC. Forbs such as menodora (Menodora spp.), bushsunflower (Simsia calva), verbena (Verbena spp.), wild buckwheat (Eriogonum effusum), and hairy tubetongue (Siphonoglossa pilosella) make up about 8% of the HCPC. Twelve percent of the HCPC is composed of woody plants such as skeletonleaf goldeneye (Viguiera stenoloba), feather dalea (Dalea formosa), black dalea (Dalea frutescens), range ratany (Krameria erecta), acacia (Acacia spp.), pricklypear (Opuntia spp.), and yucca (Yucca spp.). Shrubs such as skeletonleaf goldeneye are more common on rough broken slopes. Fires are presumed to have occurred on this site but the frequency is unknown. These fires would have burned in a mosaic pattern due to the slopes and rock. Fires are anticipated to have favored grasses and suppressed woody plants. Climate change may also be favoring the increase of shrubs but the full effect is still uncertain. Bare ground is 5-10%. Interspaces between plants are lightly covered with litter. Under HCPC, the small amount of erosion is significant due to the shallow nature of the soil. Erosion is kept to a minimum due to the high amount of plant and rock cover. Infiltration is slow to moderate. Runoff occurs during heavier rainfall, but is slowed by rocks covering the soil and vegetative ground cover. Concentrated water flow patterns are very rare. This plant community is useful for grazing cattle, depending on slope and surface rocks, but stocking rates must remain very conservative to maintain the HCPC. During drought years, livestock should be carefully managed on the site to avoid severe overgrazing. Wildlife continue to graze the site under drought conditions. If livestock are not carefully managed, the grazing impact is likely to cause permanent changes from the Mid & Shortgrass/Shrub Community (1) to the Shrub/Shortgrass Community (2). The site also contains food and cover for antelope, mule deer, dove, quail, and other types of wildlife. The HCPC will transition (T1A) toward the Shrub/Shortgrass Community (2) if exposed to heavy grazing for long periods of time. Heavy grazing removes the grass that would carry a fire to suppress woody plants. Droughts would hasten the process. In order to prevent the transition, some form of brush control and prescribed grazing will be needed. The threshold has been crossed to the Shrub/Shortgrass community once the shrub cover reaches 40%. This site can also move toward the Introduced Grassland/Shrub (3) Community. Lehmann’s lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana) is a non-native species can establish either by range planting or from being transported from where it exists on an adjacent site. It has invasive traits but can be beneficial for grazing in some cases; especially cattle. Once established, this plant community can no longer return to the HCPC.

Figure 6. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 673 | 880 | 1076 |

| Shrub/Vine | 101 | 129 | 161 |

| Forb | 67 | 84 | 108 |

| Tree | – | – | – |

| Total | 841 | 1093 | 1345 |

Figure 7. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX0017, Mid/Shortgrass/Shrub Community. Midgrasses with Shrubs – Growth is predominately midgrasses and shrubs from June through November with peak growth from August to November..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 15 | 1 |

State 2

Shrub/Shortgrass Complex State

Community 2.1

Shrub/Shortgrass Complex Community

Figure 8. 2.1 Shrub/Shortgrass Complex Community

Continued drought and overgrazing bring an increase in hairy grama (Bouteloua hirsuta), slim tridens (Tridens muticus), perennial threeawns (Aristida spp.), broom snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae), lechuguilla (Agave lechuguilla), acacia (Acacia spp.), and other woody and weedy species that initially occupied the site in small amounts. The woody increasers begin to compete with the grasses for sunlight, nutrients, water, and space. Bare ground and soil erosion continue to increase as the site transitions into a Shrub/Shortgrass Community (2) with over 40% woody vegetation. Ground cover by litter and soil organic matter decreases. Loss of vegetation is significant and exposes the surface. More bare ground causes increases in soil temperature, soil crusting, and the potential for erosion and a decrease in water infiltration. Water runoff increases and signs of erosion become more apparent. The steep slopes found on many of these sites make erosion likely when vegetative cover is lost. It is possible to return to a Mid & Shortgrass/Shrub Community (1) with higher than normal precipitation, careful prescribed grazing, some form of brush management and prescribed grazing. All of these management practices must be integrated and is still likely to take many years. If the historic erosion and loss of topsoil and soil organic matter are severe, the site is unlikely to return to the HCPC. Once the canopy threshold is crossed, grazing deferment alone will not restore the site to the HCPC. Range planting in this climate carries a high risk and is usually done when most other plant recovery options are exhausted. Moreover, the rockiness of the soils preclude range planting as a viable practice. This plant community is still useful for grazing cattle, but stocking rates must be kept lower than under the HCPC or midgrass decline will continue. The site also contains food and cover for, mule deer, dove, quail, and other types of wildlife.

Figure 9. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 6. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 336 | 448 | 560 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 280 | 375 | 471 |

| Forb | 56 | 73 | 90 |

| Tree | – | – | – |

| Total | 672 | 896 | 1121 |

Figure 10. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX0015, Shrub/Shortgrass Community. Shrubs dominant with few shortgrasses present..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 15 | 1 |

State 3

Introduced Grassland/Shrub State

Community 3.1

Introduced Grassland/Shrub Community

The historically dominant grass species decline and are replaced by perennial threeawns, slim tridens, hairy tridens, and other short grasses. Weather variability, especially precipitation, overgrazing, lack of brush management, and elimination of fire exacerbate the change. These factors enhance the establishment of Lehman’s lovegrass. Once Lehman’s lovegrass composes > 25% of the vegetation by weight, a threshold has been crossed and the plant community can no longer return to the historic plant community. Brush management can be used to keep the shrubs at desired level.

Figure 11. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 7. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 488 | 656 | 826 |

| Shrub/Vine | 183 | 247 | 308 |

| Forb | 58 | 78 | 99 |

| Tree | – | – | – |

| Total | 729 | 981 | 1233 |

Figure 12. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX0013, Introduced Grassland/Shrub Community. Introduced grasses and shrubs dominate – Growth is predominately introduced grasses and shortgrasses with shrubs from May through October with peak growth from July to September..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 12 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

State 4

Shrub/Introduced Grassland State

Community 4.1

Shrub/Introduced Grassland Community

Continued overgrazing and no brush management facilitate a loss of grasses and palatable forbs and an increase in woody vegetation in the Shrub/Introduced Grassland Community (4). Shrubs now compose over 40% canopy. It is noted that Lehman’s lovegrass can invade the site regardless of shrub canopy if there is a seed source and cooperating weather. Brush management is necessary to return the site to the Introduced Grassland/Shrub Community (3). Prescribed grazing will allow strengthening of the grasses to help arrest the return of the shrubs. This plant community is unable to return to the HCPC.

Figure 13. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 8. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 336 | 448 | 560 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 280 | 398 | 471 |

| Forb | 56 | 73 | 90 |

| Tree | – | – | – |

| Total | 672 | 919 | 1121 |

Figure 14. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). TX0016, Shrubs/Introduced Grassland Community. Introduced grasses and shrubs dominate – Growth is predominately shrubs with introduced grasses and shortgrasses from May through October with peak growth from July to September..

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 15 | 1 |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Heavy Continuous Grazing, No Brush Management, Loss of Periodic Fires, and Drought shifts to Shrub/Shortgrass Complex Community.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Introduction of Non-native seed sources leads to Introduced Grassland/Shrub State.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Brush Management and Prescribed Grazing restores to Mid & Shortgrass/Shrub State.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

Transition T2A

State 2 to 4

Heavy Continuous Grazing, No Brush Management, Drought, and Introduction of Non-native seed sources lead to Shrub/Introduced Grassland Complex State.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Heavy Continuous Grazing, Drought and No Brush Management leads to Shrub/Introduced Grassland Complex State.

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 3

Brush Management and Prescribed Grazing leads to Introduced Grassland/Shrub State.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

Additional community tables

Table 9. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Midgrasses | 404–644 | ||||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 112–280 | – | ||

| black grama | BOER4 | Bouteloua eriopoda | 67–112 | – | ||

| tanglehead | HECO10 | Heteropogon contortus | 62–112 | – | ||

| cane bluestem | BOBA3 | Bothriochloa barbinodis | 62–112 | – | ||

| 2 | Midgrass | 84–135 | ||||

| green sprangletop | LEDU | Leptochloa dubia | 84–135 | – | ||

| 3 | Shortgrasses | 41–67 | ||||

| blue grama | BOGR2 | Bouteloua gracilis | 22–34 | – | ||

| hairy grama | BOHI2 | Bouteloua hirsuta | 22–34 | – | ||

| 4 | Shortgrasses | 41–67 | ||||

| tobosagrass | PLMU3 | Pleuraphis mutica | 41–67 | – | ||

| 5 | Midgrasses | 84–135 | ||||

| Arizona cottontop | DICA8 | Digitaria californica | 22–56 | – | ||

| bush muhly | MUPO2 | Muhlenbergia porteri | 17–39 | – | ||

| plains bristlegrass | SEVU2 | Setaria vulpiseta | 11–28 | – | ||

| plains lovegrass | ERIN | Eragrostis intermedia | 11–28 | – | ||

| 6 | Shortgrasses | 41–67 | ||||

| threeawn | ARIST | Aristida | 22–34 | – | ||

| slim tridens | TRMU | Tridens muticus | 11–34 | – | ||

| fall witchgrass | DICO6 | Digitaria cognata | 11–22 | – | ||

| 7 | Shortgrasses | 17–27 | ||||

| low woollygrass | DAPU7 | Dasyochloa pulchella | 6–17 | – | ||

| sand dropseed | SPCR | Sporobolus cryptandrus | 6–17 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 8 | Forbs | 45–85 | ||||

| gumhead | GYGL | Gymnosperma glutinosum | 11–22 | – | ||

| menodora | MENOD | Menodora | 11–22 | – | ||

| chickenthief | MEOL | Mentzelia oligosperma | 11–22 | – | ||

| awnless bushsunflower | SICA7 | Simsia calva | 11–22 | – | ||

| vervain | VERBE | Verbena | 6–17 | – | ||

| Gregg's tube tongue | JUPI5 | Justicia pilosella | 6–17 | – | ||

| spreading buckwheat | EREF | Eriogonum effusum | 6–17 | – | ||

| broom snakeweed | GUSA2 | Gutierrezia sarothrae | 6–17 | – | ||

| 9 | Annual Forbs | 0–22 | ||||

| Forb, annual | 2FA | Forb, annual | 0–22 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 10 | Shrubs/Vines | 58–94 | ||||

| resinbush | VIST | Viguiera stenoloba | 17–28 | – | ||

| featherplume | DAFO | Dalea formosa | 6–17 | – | ||

| black prairie clover | DAFR2 | Dalea frutescens | 6–17 | – | ||

| Texas swampprivet | FOAN | Forestiera angustifolia | 6–17 | – | ||

| littleleaf ratany | KRER | Krameria erecta | 6–17 | – | ||

| 11 | Shrubs/Vines | 25–40 | ||||

| bush croton | CRFR | Croton fruticulosus | 6–17 | – | ||

| gumhead | GYGL | Gymnosperma glutinosum | 6–17 | – | ||

| mariola | PAIN2 | Parthenium incanum | 6–17 | – | ||

| skunkbush sumac | RHTR | Rhus trilobata | 6–17 | – | ||

| 12 | Shrubs/Vines | 8–17 | ||||

| lechuguilla | AGLE | Agave lechuguilla | 2–11 | – | ||

| tree cholla | CYIMI | Cylindropuntia imbricata var. imbricata | 2–11 | – | ||

| sotol | DASYL | Dasylirion | 2–11 | – | ||

| Texas sacahuista | NOTE | Nolina texana | 2–11 | – | ||

| pricklypear | OPUNT | Opuntia | 2–11 | – | ||

| yucca | YUCCA | Yucca | 2–11 | – | ||

| 13 | Shrubs/Vines | 0–17 | ||||

| acacia | ACACI | Acacia | 0–6 | – | ||

| brickellbush | BRICK | Brickellia | 0–6 | – | ||

| Drummond's clematis | CLDR | Clematis drummondii | 0–6 | – | ||

| Christmas cactus | CYLE8 | Cylindropuntia leptocaulis | 0–6 | – | ||

| lotebush | ZIOB | Ziziphus obtusifolia | 0–6 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

The Mid & Shortgrass/Shrub Community (1) is habitat for antelope, mule deer, songbirds, birds of prey, small mammals, and predators such as coyote, bobcat, and mountain lion. As the site changes to the Shrub/Shortgrass Community (2) it becomes less suitable for some species due to the increase in bare ground and erosion and corresponding lack of cover, structure and food plants. When it transitions to the Introduced Grassland/Shrub Community (3) the introduced grasses displace many of the native grasses and forbs utilized by indigenous wildlife. The Shrub/Introduced Grassland Community (4) provides low diversity.

Cattle, sheep, and goats can use this site, but the rocky ground and slopes make it difficult for livestock, especially cattle, to reach some forage areas. Cattle find the best forage in the Mid & Shortgrass/Shrub Community (1). As this site reaches the Shrub/Shortgrass Community (2), they usually cannot find enough forage to be thrifty. More grass forage is available in the Introduced Grassland/Shrub Community (3). As the site transitions to the Shrub/Introduced Grassland Community (4) the amount of forage for cattle declines until they can no longer find enough to meet their needs. Carrying capacity in the Trans-Pecos will vary greatly from year to year depending on the episodic precipitation.

Mule deer find good overall habitat on the Igneous Hill and Mountain Desert Grassland. They need to eat high protein forbs and browse to survive and cannot utilize the lower-protein high-fiber grasses. Quail and dove prefer a combination of low shrubs, bunch grass, bare ground, and forbs. Game bird species such as mourning and white dove and scaled quail are usually present on the site. Smaller mammals present include rodents, jackrabbit, cottontail rabbit, raccoon, skunk, possum and armadillo. Mammalian predators like coyote, bobcat, and mountain lion are likely to be found at the site. Numerous species of snakes and lizards are native to the site.

Non-game species of birds found on this site include songbirds and birds of prey. Habitat on this site that provides a large diversity of grasses, forbs and shrubs will support a variety and abundance of songbirds. Birds of prey are important to keep the numbers of rodents, rabbits and snakes in balance.

Because wildlife species are specialized in their habitat, no attempt is made in this document to provide complete habitat information. Professional guidance should be sought specific to the species of interest.

Plant Preference by Animal Kind:

This rating system provides general guidance as to animal preference for plant species. Grazing preference changes from time to time, especially between seasons, and between animal kinds and classes. It also changes depending upon the grazing experience of the animals. Grazing preference does not necessarily reflect the ecological status of the plant within the plant community.

Preferred – Percentage of plant in animal diet is greater than it occurs on the land

Desirable – Percentage of plant in animal diet is similar to the percentage composition on the land

Undesirable – Percentage of plant in animal diet is less than it occurs on the land

Not Consumed – Plant would not be eaten under normal conditions. Plants are only consumed when other forages are not available.

Toxic – Rare occurrence in diet and, if consumed in any tangible amounts results in death or severe illness in animal

Hydrological functions

The Igneous Hill and Mountain Desert Grassland is a well-drained, shallow, stony upland. Its soils are moderately to very slowly permeable. Under historic climax condition the grassland vegetation intercepted and utilized much of the incoming rainfall in the soil. There was some runoff during extended rains. Good ground cover kept runoff clear and slow. Outcrops of igneous bedrock allowed limited deep percolation to ground water. The presence of stones and rock outcrops enhance the effectiveness of rainfall, especially small rainfall events, by concentrating it on a smaller surface area. When the site changes from grassland to shrub community there is a loss of vegetated cover resulting in faster runoff that carries soil particles away. Less of the rainfall is intercepted and infiltrated into the soil.

Recreational uses

The Igneous Hill and Mountain Desert Grassland site is well suited for many outdoor recreational uses including hunting, hiking, and bird watching. Its scenic beauty and topography make it a unique site, and colorful forbs can be found on or near the site throughout the spring and summer. Big Bend National Park is found in the southern portion of MLRA 42. It is well known for its scenic mountain desert grass and shrublands, including many Igneous Hill and Mountain Desert Grasslands.

Wood products

None.

Other products

None.

Other information

None.

Supporting information

Other references

1. Archer S. 1994. Woody plant encroachment into southwestern grasslands and savannas: rates, patterns and proximate causes. In Ecological implications of livestock Herbivory in the West, Ed M Vavra, W Laycock, R Pieper, pp13-68, Denver, CO: society for Range Management

2. Brewer, Clay E., Harveson, Louis A. 2005. Diets of Bighorn Sheep in the Chihuahuan Desert, Texas.

3. Downie, A. E. 1978. Terrell County, Texas, its past- its people. San Angelo, Texas: Rangle Printing.

4. Gould F. 1978. Common Texas Grasses: an illustrated guide. College Station, Texas: Texas A & M Press.

5. Hardy, Jean Evans. 1997. Flora and Vegetation of the Solitario Dome, Brewster and Presidio Counties, Texas. A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Council Sul Ross State University.

6. Hart, Charles R. et al. 2003. Toxic Plants of Texas. Texas Cooperative Extension. Texas A&M University System.

7. Heischmidt RK, Stuth, Eds. 1991 Grazing Management: an ecological perspective. Portland, Oregon: Timberline Press

8. Henklein, D.C. 2003. Vegetation alliances and associations of the Bofecillos Mountains and plateau. Thesis, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, TX.

9. Keller, David W. 2005. Below The Escondido Rim: A History of the O2 Ranch in the Texas Big Bend. Alpine, Texas: Center For Big Bend Studies, Sul Ross State University.

10. Langford, JO. 1952. Big Bend: A Homesteader’s Story. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

11. MacLeod, William. 2003. Big Bend Vistas: a geological exploration. Austin, Texas: Capital Printing Company.

12. McPherson, Guy R. 1995. The Desert Grassland. Chapter 5: The Role of Fire in the Desert Grasslands. Tucson, Arizona. The University of Arizona Press.

13. Powell, A. Michael. 1998. Trees and Shrubs of the Trans-Pecos and Adjacent Areas. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

14. Thomas, Jack W and D Toweill. 1982. Elk of North America. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books.

15. Tyler, Ron C. 1996. The Big Bend: a history of the last Texas frontier. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press.

16. USDA/NRCS Soil Survey Manuals for Jeff Davis, Pecos, and Reeves Counties

17. Van Devender, Thomas R. 1995. The Desert Grassland. Chapter 3: Desert Grassland History. Tucson, Arizona: The University of Arizona Press.

18. Warnock, Barton. 1977. Wildflowers of the Davis Mountains and the Marathon Basin. Alpine, Texas: Sul Ross State University.

19. Wauer, Roland H. 1973. Naturalist’s Big Bend. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Peregrine Productions.

20. Weniger, D. 1984. The Explorer’s Texas: The Lands and Waters, Vol 1. Austin, Texas: Eakin Press

The following individuals assisted with the development of this site description:

Mr. Charles Anderson –Rangeland Management Specialist- NRCS; San Angelo, Texas

Dr. Louis Harveson – Department Chair Department of Natural Resource Management, Sul Ross State University

Mr. Preston Irwin – Rangeland Management Specialist-NRCS; Fort Stockton, Texas

Dr. Lynn Loomis - Soil Scientist-NRCS; Marfa, Texas

Mr. Rusty Dowell, Resource Soil Scientist, NRCS, San Angelo, Texas

Mr. Wayne Seipp, Resource Team Leader, NRCS, Marfa, Texas

Mr. Justin Clary – Rangeland Management Specialist – NRCS; Temple, Texas

Dr. AM Powell, Professor Emeritus – Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas

Contributors

Duckworth-Cole, Inc., College Station, Texas, Michael Margo, RMS, NRCS, Marfa, Texas

Unknown

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Michael Margo, RMS, NRCS, Marfa, Texas |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | Zone RMS, San Angelo, Texas, 325-944-0147 |

| Date | 02/02/2010 |

| Approved by | Kent Ferguson |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

None. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

None, except following high intesity storms, when short (less than 1 m) and discontinuous flow patterns may appear. Flow patterns in drainages are linear and continuous. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

None. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

1-3% bare ground. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

None. -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

In drainages, there can be significant amounts of litter moved long distances. On most of the site, minimal and short distance (<5ft) of litter movement associated with high intense rainfall. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Stability class ranging from 4-5 at the surface. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

Soil surface 2-4 inches thick, brown (10YR 4/3), weak fine granular structure ranging to a medium subangular blocky structure. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

A high canopy cover of midgrass bunch and stoliniferous grasses will help minimize runoff and maximize infiltration. Grasses should comprise approximately 80% of total plant compostion by weight. Shrubs will comprise about 15% by weight. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

None. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm-season stoloniferous grasses >Sub-dominant:

Warm-season perennial bunchgrasses > Warm-season narrowleaf bunchgrasses > Shrubs >Other:

Subshrubs > Fibrous and Succulent leaves > Perennial forbs > Annual forbs > Annual grasses > Warm-season narrowleaf shortgrassesAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

All grasses will show some mortality and decadence in addition to annual forbs. Mid/tall perennial shrubs will show some mortality or decadence only after prolonged and severe droughts. Subshrubs will be less resistant to severe droughts than mid/tall perennial shrubs. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Litter is primarily herbaceous. -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

750-1200 pounds per acre. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Lehmann's lovegrass is one potential invasive species that may occur on this site. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All species should be capable of reproduction except during periods of prolonged drought conditions, heavy natural herbivory, or intense wildfires.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.