Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site EX043B05C122

Loamy Bighorn Mountains Sub-alpine Zone

Last updated: 3/05/2025

Accessed: 12/17/2025

General information

Approved. An approved ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model, enough information to identify the ecological site, and full documentation for all ecosystem states contained in the state and transition model.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 043B–Central Rocky Mountains

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA):

43B – Central Rocky Mountains – This MLRA is extensive including Montana, Idaho, Wyoming and a small portion in Utah. MLRA 43B includes the Rocky Mountains. A revision of the MLRA's in 2006 lead to the inclusion of the foothills with the mountains for much of Wyoming. Cartographic standards limited the ability to capture the foothills as a separate MLRA .

Further information regarding MLRAs, refer to: United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2006. Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbook 296.

Available electronically at: http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/ref/?cid=nrcs142p2_053624#handbook.

LRU notes

Land Resource Unit (LRU):

43B05 (WY): Based on the shifts in geology, precipitation patterns and climatic factors, as well as elevations and vegetation shifts, the Bighorn Mountains with the Owl Creek and Bridger ranges were divided into LRU 05. Further division of this LRU is necessary due to the climatic gradient moving from the foothills to the summit, as well as east face versus west face of the mountain. The Subalpine zone is noted by Subset C, the higher elevation ring with 19 plus inches of precipitation consisting of a persistent snowpack and limited growing days. This subset stops at tree line where it then transitions into the alpine zone of the mountain (Subset D).

Moisture Regime: Typic Ustic

Temperature Regime: Cryic

Dominant Cover: Rangeland – Montane Grassland

Representative Value (RV) Effective Precipitation: 19-25” inches (482 – 635 mm)

RV Frost-Free Days: 50-55 days

Classification relationships

Hierarchical Classification Relationships

Relationship to Other Established Classification Systems:

National Vegetation Classification System (NVC):

2 Shrub & Herb Vegetation

2.B Temperate & Boreal Grassland & Shrubland

2.B.2 Temporate Grassland & Shrubland

2.B.2.Na Western North American Grassland & Shrubland

M048 Central Rocky Mountain Montane-Foothill Grassland & Shrubland

A3965 Central Rocky Mountain Subalpine Dry Idaho Fescue Grassland

CEGL001611 – Festuca idahoensis – Carex obtusata Grassland or

CEGL001612 – Festuca idahoensis – Danthonia intermedia Grassland or

CEGL001899 – Festuca idahoensis – Carex scirpoidea Grassland

Ecoregions (EPA):

Level I: 6 Northwestern Forested Mountains

Level II: 6.2 Western Cordillera

Level III: 6.2.(10) Middle Rockies

Level IV: 6.2.(10)17.k Granitic Subalpine Zone, and

(10)17.m Dry Mid-Elevation Sedimentary Mountains

Ecological site concept

• Site receives no additional water.

• Slope is <20%

• Soils are:

o Derived from sedimentary parent materials.

o Textures range from very fine sandy loam to clay loam in top 4” (10 cm) of mineral soil surface

o Clay content is or = 32% in top 4” (10 cm) of mineral soil surface

o Each following subsurface horizon has a clay content of <35% by weighted average in the particle size control section

o Moderately deep to very deep (20-78+ in. (50-200+ cm)

o <3% stone and boulder cover and <20% cobble and gravel cover

o Not skeletal (<35% rock fragments) within 20” (51 cm) of mineral soil surface

o None to Slightly effervescent throughout top 20” (51 cm) of mineral soil surface

o Non-saline, sodic, or saline-sodic

The Loamy ecological site concept is based on minimal (none to slight) influence from salts, carbonates, gypsum or other chemistry within the top 20 inches (51 cm) of the mineral soil surface. Increased precipitation and cool soil temperatures allows soluble salts and calcium carbonates to move lower in the profile with the increased potential for deeper percolation of water, in comparison to the mesic/frigid counterparts. The main site characteristic is a moderate to very deep soil profile with moderate textures of 18-35% clays, textures range from sandy loam to clay loam. The plant community will transition to a higher composition of rhizomatous wheatgrass as well as king-spike fescue with Idaho fescue as the clays increase (shift to clayey or dense clay site).

Loamy is also found in complexes with shallow and very shallow soils which generally have a higher rate of King-Spike fescue and bare ground, lower production and increase in pincushion forbs. Mountain big sagebrush is prevalent across all of these sites to an extent. The granitic counter-part to this site will look very similar with the absence of mountain big sagebrush being the biggest indicator.

Previously, the Loamy 20”+ precipitation zone, High Mountains, covered all of mountain ranges that are part of the central Rocky Mountains. This original concept was too broad in nature, lending to a division into ecological sites according to LRU’s, to better match climatic, geomorphologic and geologic differences. Although the concept is similar, plant production and community composition will shift between LRU’s.

Associated sites

| R043BY162WY |

Shallow Loamy High Mountains Shallow Loamy sites are generally located on the break of slopes, on or surrounding rock outcrops before it transitions into more gently rolling landforms with deeper soils. Similar plant communities with more pincushion forbs and a higher percentage of King spike fescue, but a marked reduction in production and increased bare ground. |

|---|---|

| R043BY130WY |

Overflow High Mountains Overflow site are found in concave areas that have concentrated flows within a loamy or other similar sites. This site is characterized by increased tall, water loving species and shrub cover. The concave nature with increased capture of overland flows increases productivity above a Loamy site and the transition to shrubby cinquefoil is an easy key on the landscape. |

Similar sites

| R043BY122WY |

Loamy High Mountains This site is the basis for the current site development, however, the site is narrowed to the characteristics specific to the Bighorn Mountains, where this original site was broader based covering the Absaroka, Owl Creek, Bridger, and Wind River Range. |

|---|---|

| R043BY322WY |

Loamy (Ly) 15-19” Foothills and Mountains East Precipitation Zone This site is the 15-19 |

| R043BY222WY |

Loamy Foothills and Mountains West This site is the 15-19 |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Festuca idahoensis |

Legacy ID

R043BX122WY

Physiographic features

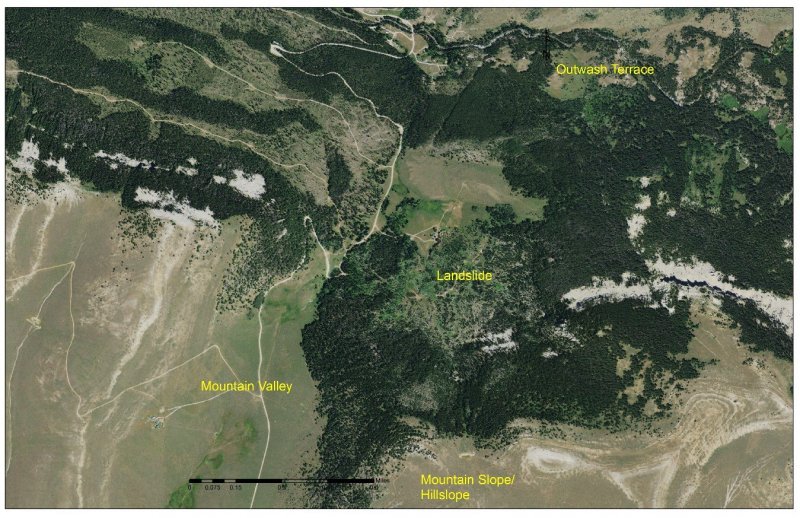

The Loamy ecological site generally occurs on slopes ranging from near level to 20%. The landform features are a combination of residuum, alluvial, colluvium, and eolian materials derived from glacial, landslide, and tectonic movement of sedimentary rock. Hillslopes or mountain slopes, landslides, outwash terraces or benches, mountain valleys along narrow drainages (marked as drainage ways) are identified landforms where this site exists. Varied topography and broken or overlapping landforms within this landscape creates a situation where one landform may have a complex of ecological sites, observed through the variability of plant species from upper to lower extents along a landform. Some level of variability is allowed within the description to incorporate variability of deposition and scour of snow, as well as wind desiccation. In the investigative process, this group of landforms was described as follows: Rocky Mountain Systems Division Middle Rocky Mountains Province with a landscape classified as Mountains or Mountain Range (Geomorphic Description System v. 4.2).

A closer examination of surface and bedrock geology was completed to help explain or determine specific landforms. From the USGS Surficial Geology GIS layer, the surface geology for this ecological site includes:

• glacial deposits

• landslide

• bedrock and glaciated bedrock including hot spring deposits and volcanic necks

• residuum with alluvium,

Each of which are mixed with one or more of the following scattered deposits: slopewash, residuum, grus, alluvium, colluvium, eolian, (tertiary) landslides, glacial, periglacial, and/or bedrock outcrops.

The complexes of soil components mapped on these landforms are typically separated by chemistry, rock fragments throughout the profile or depth to bedrock (lithic or paralithic material). Many of these landforms are erosional and have both deep and shallow soils. Many times the geology of the parent material as well as erosional influences of surrounding landforms will create a mosaic of sites. The soils derived from sedimentary rock are dominant in the Loamy ecological sites. Small micro-climates occur with aspect, erosional influences, and landform breaks that will create vegetation shifts within this site. The break between one ecological site and another (and the representative plant community for each) is often a broad and non-descript band between the two sites. This can make it difficult when on the landscape to identify clearly which site is dominant for a specific point along that transitional gradient.

Depth to water table is stated to occur below 78 inches (200 cm) for the calendar year. This site is also characterized by no additional moisture capture; it is commonly associated with isolated pockets (concave areas) or shallow drains where snowmelt or surface moisture collects briefly creating an overflow site, with a more robust plant community. Valley floors or “bowls” on the landscape, sag ponds or small wetland depressions or springs, may occur in close proximity to a loamy site.

Figure 1.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Mountain range

> Mountain slope

(2) Mountain range > Mountain valley (3) Mountain range > Landslide (4) Mountain range > Outwash terrace |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Negligible to low |

| Elevation | 7,800 – 11,850 ft |

| Slope | 20% |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

Annual precipitation and modeled relative effective annual precipitation ranges from 20 to 30+ inches (508 – 762 mm). Snows are heavy and usually remain in place during winter (November through May). Annual snowfall averages 40 to 75+ inches per year. Wide fluctuations may occur in yearly precipitation and result in more dry years than those with more than normal precipitation. Although annual precipitation is relatively evenly distributed through the year, the driest portion of the year generally occurs in August into mid-September.

Temperatures show a wide range between summer and winter and between daily maximums and minimums, due to the high elevation and dry air, which permits rapid incoming and outgoing radiation. Mean annual temperature is less variable between winter and summer, due to these same shifts in maximum and minimum temperatures. Cold air outbreaks from Canada in winter move rapidly from northwest to southeast and account for extreme minimum temperatures. Chinook winds may occur in winter and bring rapid rises in temperature.

High winds are generally less frequent than over other areas of Wyoming, and are most common in canyon or valley systems. Brief periods of strong winds will occur in conjunction with an occasional storm, with gusts exceeding 50 mph. Growth of native cool-season plants begins about June 1st at lower elevations, and can be as late as July 15th at higher elevations. Growth will occur into the first and second week of September.

Review of a 30 year trend of data for average temperature as well as average precipitation, there has been a shift in when and the rate of spring warm up and first frost hit with the decline in average precipitation. These shifts have produced a swing in the rate of snow melt, decreasing persistent snow packs, and reducing the available moisture in the hydrologic system creating a compounding drought effect for both high and low elevations. Early frosts, with dry open fall and spring periods has created a more arid environment, affecting plant vigor and health resulting in high rates of winter kill, plant disease susceptibility.

For detailed information visit the Natural Resources Conservation Service National Water and Climate Center at http://www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov/. “Burgess Junction" is the representative weather stations within LRU E Subset C. The following graphs and charts are a collective sample representing the averaged normals and 30 year annual rainfall data for the selected weather station from 1981 to 2010.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 7 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 47 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 20 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 7 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 47 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 20 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 7 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 47 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 20 in |

Figure 2. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 3. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 4. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 6. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 7. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BURGESS JUNCTION [USC00481220], Dayton, WY

Influencing water features

The characteristics of these upland soils have no influence from ground water (water table below 78 inches (200 cm)) and have minimal influence from surface water/overland flow. There may be isolated features that are affected by snow pack that persists longer than surrounding areas due to position on the landform (shaded/protected pockets).

Soil features

The soils of this site are moderately deep to very deep (greater than 20 inches (51 cm) to bedrock), moderately well to well drained, and moderately slow to moderate permeability. The soil characteristics having the most influence on the plant community are depth, texture and the chemistry.

The general soil profile has a sandy loam or loam cap over sandy clay loams and clay loams. These soils are moderately deep to very deep and may have channers lower in the profile (below 20 inches (51 cm)). Areas within the Bighorn Mountains are influenced by dolomite or limestone. However, for this ecological site the concentrations of carbonates occur below the depth of plant influence (20 inches (51 cm)), or occur as small mass/nodules in low concentrations throughout the profile. Overall the pH, CCE, EC, and SAR are neutral or moderately acidic. The range of values characterizing this site are listed below. As the amount of calcium carbonates increases beyond the stated ranges, near the surface or lower in the profile, the soil is no longer in the loamy ecological site and needs to be re-correlated to the proper ecological site.

Many of the landforms where these soils occur have an alluvial influence leaving a surface layer of gravels and cobbles. Typically, this surface lag will be less than 10% cover, however some areas may have greater than 15% of gravels and a few cobbles. This layer does not extend very deep in the profile and has minimal influence on the plants.

Major soil series correlated to this site include: Owen Creek, Passcreek, Echemoor, and Bynum. This list of soil series is subject to change upon completion and correlation of the initial soil surveys: WY650, WY603, WY719; as well as revisions to completed soil survey: WY043, WY619, and WY633.

Figure 8.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

sedimentary rock

(2) Alluvium – sedimentary rock (3) Colluvium – sedimentary rock |

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Loam (2) Clay loam (3) Silt loam (4) Very fine sandy loam |

| Drainage class | Somewhat poorly drained to moderately well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate to moderately rapid |

| Depth to restrictive layer | 20 in |

| Soil depth | 20 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 15% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 5% |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (Depth not specified) |

14% |

| Clay content (Depth not specified) |

18 – 35% |

| Electrical conductivity (Depth not specified) |

4 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (Depth not specified) |

5 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (Depth not specified) |

4.8 – 8 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

15% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

10% |

Ecological dynamics

Potential vegetation on this site is estimated at 70% grasses, 20% forbs, and 10% shrubs/woody plants. Loamy soils originate from two distinct parent materials influencing the specific species, granitic and sedimentary. The community dominance will vary from one parent material to the other, with the most significant variation being the lack of mountain big sagebrush on sites derived from granitic (intrusive) parent materials. However, there is a shift in the vigor and response of Idaho fescue between these two parent materials. Because of these variations, it was warranted to separate the loamy soils into granitic loamy ecological site and loamy ecological site (sedimentary materials).

The loamy ecological site plant communities are dominated by perennial, mid-stature cool-season bunchgrasses such as Columbia needlegrass, Idaho fescue, slender wheatgrass, and bluebunch wheatgrasses. Rhizomatous wheatgrasses and other mid-stature grasses such as cusick’s bluegrass, prairie junegrass, spike trisetum, one-spike and timber oatgrass, bentgrass, Letterman and Richardson needlegrass, mountain and nodding brome, oniongrass, and a variety of sedges are common. There is a wide variety of forbs that bloom at varying intervals through the summer creating seasons of color. Mountain big sagebrush and fringed sagewort are the dominant woody species.

Deterioration of this site will occur as a response to frequent and severe grazing, lack of fire, and/or drought. As the site declines, Columbia needlegrass, slender wheatgrass, and Idaho fescue will decline; while species such as fringed sagewort, mountain big sagebrush, buckwheat, yarrow, rhizomatous wheatgrass and less palatable grasses such as letterman’s needlegrass will increase. Kentucky bluegrass may invade, as well as dandelion.

Mountain big sagebrush will become dominant with the absence of fire. Wildfires are often actively controlled, however the use of mosaic or spot treatments with fire as well as control with herbicides has replaced the historic role of wildfire on this site.

The ecological states and community phases as well as the dynamic processes driving the transitions between these communities have been determined by studying this ecological site under all management scenarios, including those that do not include cattle grazing. Trends in plant communities going from heavily grazed areas to lightly grazed areas, seasonal use pastures, and historical accounts have been used.

The following State and Transition Model (STM) Diagram has five fundamental components: states, transitions, restoration pathways, community phases and community pathways. The state, designated by the bold box, is considered to be a set of parameters with thresholds defined by ecological processes. A State can be a single community phase or suite of community phases. The reference state is recognized as State 1. It describes the ecological potential and natural range of variability resulting from dynamic ecological processes occurring on the site. The designation of alternative states (State 2, etc) in STMs denotes changes in ecosystem properties that cross a certain threshold.

Transitions are represented by the arrows between states moving from a higher state to a lower state (State 1 - State 2) and are denoted in the legend as a “T” (T1-2). They describe the variables or events that contribute directly to loss of state resilience and result in shifts between states. Restoration pathways are represented by the arrows between states returning back from a lower state to a higher state (State 2 - State1 or better illustrated by State 1

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

| T1A | - | Non-use (lack of use) or lack of fire allows Mountain big sagebrush to increase in crown cover and density, making the transition to the sagebrush/mixed grass state. Heavy, continuous season-long grazing and no fire will shift this state to the mixed shrubs/forbs community within state 2. |

|---|---|---|

| T1B | - | Disturbance of the reference site will encourage the establishment of noxious weeds if a seed source is present. Heavy use, trailing or access roads/routes, as well as drought, season-long use, or impact of insects/disease can open the canopy to non-native/invader species. |

| R2A | - | Grazing management and possibly brush management with prescribed fire or chemical control may be needed reduce the woody overstory and allow the grasses to recover. |

| T2A | - | Once a site has transitioned to this state, the increased bare ground and weakened plant structure leaves the community vulnerable to encroachment or species creep by non-native species such as Kentucky bluegrass, dandelions, smooth brome, and in some instances conifers. Control of these species is difficult and complete eradication may not be possible. |

| T4A | - | Planned disturbances, seeding, or development activities provides the open niche for invasive species to invade a location. Ground disturbance of a site will encourage weedy species, especially when introduced into the system on equipment. |

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

| 2.1A | - | Drought, season-long use or other disturbances impact grass/grass-like cover and encourage forbs as well as woody species. |

|---|---|---|

| 2.2A | - | Targeted rest/deferred grazing or rotational grazing will help to manage the forb component and will encourage the grasses/grass-like species aiding in the shift back to the 2.1 community. |

State 3 submodel, plant communities

| 3.1A | - | Non-native species seeds utilize the weakened condition of the encroached community to establish a foothold. |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1B | - | The mechanism driving woody encroachment provides the opportunity for invasive species establishment. Drought, human impact, or animal disturbance can exacerbate this transition. |

| 3.2A | - | The encroachment of non-native species provides the opportunity for more aggressive invasive species to take over a community. Drought, human or animal disturbance can exacerbate this transition. |

State 4 submodel, plant communities

| 4.1A | - | Completion of a re-vegetation project with seeding, integrated pest management, and long-term prescribed grazing or other managed use of a landscape is needed to shift a disturbed community back to a representative or functional plant community. |

|---|---|---|

| 4.2A | - | If a reclaimed/restored site is not managed for the established community, the community will revert back or will fail to establish converting once again to the degraded community phase. Lack of management can include non-use, loss of natural disturbance regimes, or over-use by large herbivores or humans. |

State 1

Mixed Grasses/Shrubs

Mixed Bunchgrass/Sagebrush State (State 1 - Reference) evolved with grazing by large herbivores and is well suited for grazing by domestic livestock. Potential vegetation is estimated at 70% grasses or grass-like plants, 20% forbs, and 10% woody plants.

Characteristics and indicators. The community is characterized by the key species including: Columbia needlegrass, slender wheatgrass, needleleaf sedge, Idaho fescue, and bluebunch wheatgrass. Other grasses may include mutton and Cusick’s bluegrass, bentgrasses, prairie junegrass, onespike and timber oatgrass, thickspike wheatgrass, mountain brome and spike trisetum. Forbs include: cutleaf anemone and pale mountain dandelion. Increaser species are: bluegrasses, old man’s whiskers, rosy pussytoes, lupine, field chickweed, phlox and cinquefoil (herbaceous). Mountain big sagebrush is the dominant woody plant, but other species such as fringed sagewort, wood's rose, and shrubby potentilla may occur.

Resilience management. Resiliency of this State is reliant on the persistence of the native grasses and forbs in balance with a sagebrush canopy. Timing and intensity of utilization of the herbaceous species, as well as climatic variability and intensity of disturbance are drivers of change in this system.

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Columbia needlegrass (Achnatherum nelsonii), grass

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), grass

Community 1.1

Mixed Grasses/Sagebrush

Figure 9. Fall view of the reference Loamy site on subalpine zone of the Bighorn mountains.

The reference community (1.1) is declining in occurrence on the landscape. The introduction and creep of non-native species from historic use, through to the increase of land use has allowed species such as smooth brome, common dandelion, Kentucky bluegrass, and others to become naturalized in the communities. Combined with the non-natives, the greater threat of invasive species has put the reference state and community at great risk. Mountain big sagebrush is a component of this plant community, but will remain at 10% or less canopy cover. As the sagebrush density/frequency increases, the higher the risk for other undesirable species increases. Sedimentary parent materials support a sagebrush community more than granitic. Granite based soils tend to support low growing shrubs such as fringed sagewort, cudweed sagewort, rather than the mountain big sagebrush communities, although you can find sagebrush on granitic sites. The herbaceous component of this site will also shift between sedimentary and granitic soils. Idaho fescue will be dominant on granitic soils, while Columbia needlegrass and rhizomatous wheatgrasses will dominate on sedimentary soils. On granitic soils, dense spikemoss is common; while on sedimentary soils bedstraw is common, upland sedge species will vary between parent materials also. The total annual production (air-dry weight) of this state is about 2500 lbs./acre, but it can range from about 1800 lbs./acre in unfavorable years to about 3000 lbs./acre in above average years. This production is based on the historic records used to write the initial Loamy 20”+ High Mountains ecological site.

Resilience management. Rangeland Health Implications/Indicators: This plant community is extremely stable and well adapted to the Central Rocky Mountain climatic conditions. The diversity in plant species allows for high drought tolerance. This is a sustainable plant community.

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Columbia needlegrass (Achnatherum nelsonii), grass

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), grass

-

slender wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus), grass

Figure 10. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 1250 | 1775 | 2000 |

| Forb | 250 | 350 | 500 |

| Shrub/Vine | 300 | 375 | 500 |

| Total | 1800 | 2500 | 3000 |

Table 6. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0-1% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 0-10% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 50-75% |

| Forb foliar cover | 5-15% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 5-10% |

| Litter | 10-15% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-15% |

Table 7. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0% |

| Forb basal cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 5-10% |

| Litter | 10-15% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-15% |

Table 8. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (ft) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | – | 0-5% | 1-5% | 5-10% |

| >0.5 <= 1 | – | 0-10% | 10-25% | 5-15% |

| >1 <= 2 | – | 0-10% | 10-50% | 0-3% |

| >2 <= 4.5 | – | 0-5% | 1-5% | 0-2% |

| >4.5 <= 13 | – | – | – | – |

| >13 <= 40 | 0-1% | – | – | – |

| >40 <= 80 | – | – | – | – |

| >80 <= 120 | – | – | – | – |

| >120 | – | – | – | – |

State 2

Sagebrush Dominated

This state is a degraded state, driven by a dense shrub community, predominantly mountain big sagebrush. Initially, grasses persist in the understory, but with continued heavy use, the grass understory will become forb dominated.

Characteristics and indicators. Shrub canopy is 20% and can become greater than 40%. Bluegrasses and Idaho fescue are the prominent grasses that persist in the understory with a variety of forbs such as cinquefoil, geranium, and field chickweed.

Resilience management. Resilience of this State relies on the persistence of the sagebrush canopy and maintaining native vegetation within the understory. This state is vulnerable to encroachment of non-native/invaders species. Fire is also a driver of change for this State.

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), grass

-

Cusick's bluegrass (Poa cusickii), grass

-

mountain brome (Bromus marginatus), grass

Community 2.1

Sagebrush/Mixed Grasses

Figure 11. Sagebrush dominated community with a strong grass understory.

This plant community is the result of long-term protection from grazing and fire. Mountain big sagebrush dominates the site, often exceeding 20-50% annual production and lowering herbaceous forage production. Bunchgrasses such as bluebunch wheatgrass, Columbia needlegrass, Idaho fescue, and mountain brome dominate the understory. The total annual production (air-dry weight) of this community phase is about 2000 lbs./acre, but it can range from about 1500 lbs./acre in unfavorable years to about 3000 lbs./acre in above average years.

Resilience management. Rangeland Health Implications/Indicators: This plant community is resistant to change and is relatively stable. The site is protected from excessive erosion. The biotic integrity of this plant community is usually intact, however forage value will decrease and wildlife values will shift toward different species as sagebrush continues to dominate the site. The watershed is functioning, the hydrology of the location will appear to be dryer due to the density of woody vegetation, but the area has the potential to hold more snowpack longer into the growing season.

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), grass

-

mountain brome (Bromus marginatus), grass

-

sedge (Carex), grass

Figure 12. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 9. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 750 | 900 | 1350 |

| Shrub/Vine | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| Forb | 250 | 350 | 650 |

| Total | 1500 | 2000 | 3000 |

Table 10. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0-1% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 10-30% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 50-60% |

| Forb foliar cover | 10-15% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 5-15% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-20% |

Table 11. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0% |

| Forb basal cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 5-15% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-20% |

Table 12. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (ft) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | – | 0-5% | 1-5% | 5-10% |

| >0.5 <= 1 | – | 5-10% | 10-20% | 5-15% |

| >1 <= 2 | – | 5-20% | 10-30% | 0-2% |

| >2 <= 4.5 | – | 0-5% | 0-5% | 0-2% |

| >4.5 <= 13 | – | – | – | – |

| >13 <= 40 | 0-1% | – | – | – |

| >40 <= 80 | – | – | – | – |

| >80 <= 120 | – | – | – | – |

| >120 | – | – | – | – |

Community 2.2

Dense Shrubs/Forbs

Figure 13. Shrub dominated community with a strong forb undestory.

The plant community is the result of long-term protection from grazing and fire, or grazed early to mid-summer by cattle when grasses are most susceptible, allowing forbs and sagebrush to dominate the site. Mountain big sagebrush dominates the site, often exceeding 20-50% annual production and lowering herbaceous forage production. Bunchgrasses such as bluebunch wheatgrass, Idaho fescue, and mountain brome persist in the understory, however, forbs such as lupine, field chickweed, prairie smoke, and pussytoes are more prominant. The forb composition of this site will shift in response to time and timing of precipitation as well as temperature patterns of the summer. Many areas within this ecological site have a prominent component of larkspur and deathcamas that can be very prevalent in the community one year, and then be dormant the next. The ability for forbs to persist in a non-contiguous growth cycle, allows for greater flexibility and hold greater resiliency under heavy grazing conditions. The presence of spikemoss and other ground covering forbs can impact a site over time if not addressed. There are several different opinions or theories to the reason for spikemoss on the landscape, but the overall findings show that spikemoss, although stabilizing and protection for the soil, can greatly hinder the potential of a location due to lack of exposed soil for seed rejuvenation as well as water repellency that can occur with dense coverings of spikemoss. The total annual production (air-dry weight) of this community phase is about 2000 pounds per acre, but it can range from about 1250 lbs./acre in unfavorable years to about 2750 lbs./acre in above average years.

Resilience management. Rangeland Health Implications/Indicators: This plant community is resistant to change and stable. The biotic integrity of the site is hindered due to the abundance of forbs and the lack of diversity in grass species. The site is protected from erosion when spikemoss is present, but under common conditions, erosion is accelerated due to the increase in bare ground. The watershed is functioning, but is at risk of further degradation. Water flow patterns are obvious and signs of pedestalling or terracettes are forming. Infiltration is reduced and runoff is increased from this site, having an effect on neighboring ecological communities.

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

Figure 14. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 13. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forb | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| Shrub/Vine | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 250 | 500 | 750 |

| Total | 1250 | 2000 | 2750 |

Table 14. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0-1% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 10-30% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 40-60% |

| Forb foliar cover | 5-15% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 10-20% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-20% |

Table 15. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0% |

| Forb basal cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 10-20% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-20% |

Table 16. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (ft) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | – | 0-5% | 0-5% | 5-10% |

| >0.5 <= 1 | – | 5-20% | 10-20% | 5-15% |

| >1 <= 2 | – | 5-20% | 10-30% | 0-2% |

| >2 <= 4.5 | – | 0-5% | 0-5% | 0-2% |

| >4.5 <= 13 | – | – | – | – |

| >13 <= 40 | 0-1% | – | – | – |

| >40 <= 80 | – | – | – | – |

| >80 <= 120 | – | – | – | – |

| >120 | – | – | – | – |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Drought, season-long use or other man or natural disturbances will impact the grass/grass-like herbaceous cover, encouraging the forb components to dominate in the understory of sagebrush and other woody/shrub canopy. The intensity, timing, and the point of the disturbance influence the rate of shift between the grass or forb understory, and drives the species that begin to dominate. The point of disturbance is in reference to grazing, specifically the species of grazing. Sheep allotments show a trend to shift to a more grass dominated system, where cattle grazing can trend to a more forb dominated system. Again depending on timing and intensity of use, these trends will vary. Timing of precipitation and/or the persistance of snowpack is also a factor that may the driver for a forb understory, not necessarily use or further disturbance. These areas are inclusions in the ecological site that show indication of a hydrologic shift without the persistance of a water table, no overflow indication (outside of an enhancement in vegetation), and the soils fit within the characteristics of the loamy site. The tend to be small in size on a landform scale, and whether position on the landform or a microfeature of the landform, the site benefits from its location and tends to have a higher density of forbs, and shrubs. And will tend to have different or more variety of shrub species : shrubby cinquefoil and wood's rose.

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Targeted grazing, utilizing sheep or alternative grazers, to utilize the forbs in the community will help to encourage the grasses and possibly reduce the shrub component in the community. Rest/deferred rotational grazing is needed to allow recovery of the desired grass species within the community, and timing of use will be a key factor to recovery. In some instances it may be necessary to use mechanical or chemical control of the shrubs and herbaceous forb species.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Fence | |

| Grazing Land Mechanical Treatment | |

| Native Plant Community Restoration and Management | |

| Grazing Management Plan | |

| Grazing management to improve wildlife habitat | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control |

State 3

Non-native/Invader

This state is not easily divided into two distinct communities, nor is it possible to determine a typical composition of any one community. The encroachment of woody species (conifers) into an open or sagebrush park, and the movement of non-native species into an area have increased across the mountain range. There are instances where these communities cross on the landscape, and they are at-risk of further transformation. The occurrence of these communities can be a process of time or of disturbance. Historic studies have documented conifer encroachment as well as the presence of non-native species such as Kentucky bluegrass and dandelions prior to the early 1950's. Another concern, within the Bighorn National Forest, is the threat of large scale weed invasions. Currently, most of the mountain has retained only small or isolated patches of invasive weeds. Cheatgrass has been identified as a concern on several south facing slopes on the lower flanks of the mountain range. Areas of leafy spurge, toadflax (yellow or dalmation) and thistles have been identified. Although early detection/rapid response techniques are applied for land management, limited resources make it difficult to track all current and new infestation sites. Overall, the weed infestation level is not seen as a critical concern, but the threat is growing and being monitored closely.

Characteristics and indicators. This community is driven by a significant presence (5% composition) of non-native and/or invasive species. The dominant non-native/invader species are Kentucky bluegrass, dandelions, thistles, toadflax (Dalmatian, yellow), cheatgrass, smooth brome, and field pennycress. As new species are found, this list will be adapted to include these species.

Resilience management. Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and other non-native species have a high resiliency once they have established in a community. The management of the native species is difficult, and is dependent on what specific species composition exists in the individual community. The removal or treatment of encroaching woody species is best tackled when they occur at a low intensity, before they may be seen as a concern.

Dominant plant species

-

limber pine (Pinus flexilis), tree

-

Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), tree

-

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), tree

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), grass

-

mountain brome (Bromus marginatus), grass

Community 3.1

Encroachment

Figure 15. Spruce and Fir encroachment on upland (non-forested) communities.

This plant community is in response to the lack of fire or natural disturbance that limited the establishment of forest vegetation – trees. The movement of juniper species, specifically Rocky Mountain Juniper, as well as spruce trees into open park areas is thought to be a natural succession of the forest by some, and other research shows it as a result of fire suppression. It has been noted, that with the shift in herbaceous cover, as litter accumulates, the potential for species such as spruce and juniper to establish increases. Especially in pockets where snow may catch or drift frequently. The snow catch from the taller canopy and shading provide, allows for further expanse of woody species, and will hold an impact on the herbaceous species within in the canopy. Grasses tend to become less prominent and forb species will shift, depending on the tree species and amount of crown cover. The total annual production (air-dry weight) of this state is about 2250 pounds per acre, but it can range from about 1500 lbs./acre in unfavorable years to about 3250 lbs./acre in above average years.

Resilience management. Rangeland Health Implications/Indicators: This community is at-risk of transitioning to the non-native community or to a forested land type. The state overall is stable and protected from excessive erosion. The biotic integrity of this plant community is fractured, due to the increasing presence of woody species. Forage value will decrease or the wildlife value will shift toward different species. The watershed is functioning, but with the increase in woody species (conifers/junipers), the risk of fire could decrease the stability and watershed function of the site.

Dominant plant species

-

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), tree

-

Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), tree

-

limber pine (Pinus flexilis), tree

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), grass

-

mountain brome (Bromus marginatus), grass

-

slender wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus), grass

Figure 16. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 17. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 750 | 1000 | 1350 |

| Shrub/Vine | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| Forb | 250 | 500 | 800 |

| Tree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1500 | 2250 | 3150 |

Table 18. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0-5% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 10-30% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 40-60% |

| Forb foliar cover | 5-20% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 5-20% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-15% |

Table 19. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0% |

| Forb basal cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 5-20% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-15% |

Table 20. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (ft) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | – | 0-5% | 5-10% | 0-5% |

| >0.5 <= 1 | – | 5-15% | 5-20% | 5-10% |

| >1 <= 2 | – | 5-20% | 0-20% | 0-3% |

| >2 <= 4.5 | – | 0-5% | 0-5% | 0-2% |

| >4.5 <= 13 | – | – | – | – |

| >13 <= 40 | 0-5% | – | – | – |

| >40 <= 80 | – | – | – | – |

| >80 <= 120 | – | – | – | – |

| >120 | – | – | – | – |

Community 3.2

Non-Native Dominant

Figure 17. Non-native dominated Community (Poa pratensis, Taraxicum officinale)

Transitioning from the Native Encroachment community phase (3.1) to the non-native community phase is the result of a culmination of factors including land use, proximity to transportation routes, wildlife and livestock movement, and general shift in vegetation. Minor impacts or major disturbances can allow small or isolated patches of non-native species to gain a foothold in an area. From there, succession over time, drought, or other natural or man-driven disturbances allows the spread and eventual dominance of species such as smooth brome, timothy, dandelions, Kentucky bluegrass, field pennycress and others. Many of these species, once established, cannot be eliminated from the system. Unlike their invader cousins, these species will co-exist with most native species. And do provide a desirable forage and can be managed with livestock use. Research from the 1950’s using exclosures noted that dandelions did not seem to vary from grazed to non-grazed sites, and that they seemed to persist in undisturbed areas, reasoning that they were "naturalized" species. Moving past their origin, these species hinder or shift the production and potential of the native species in the community if not managed. The wide-scale and long-term documented existence of the non-native species, specifically Kentucky bluegrass and common dandelion, has led to a coined term of "naturalized". This term has many different colloquial meanings and definitions. In this context, the species existed when initial surveys were completed on the Bighorn National Forest. Although they are identified as non-native species, originating from outside of the contiguous 48 states, the species are a functioning member of the community. These species can remain quiet or hold a minimal composition in the community, but if pressured can become dominant, and a near monoculture in some instances. The total annual production (air-dry weight) of this state is about 2000 pounds per acre, but it can range from about 1200 lbs./acre in unfavorable years to about 2800 lbs./acre in above average years.

Resilience management. Rangeland Health Implications/Indicators: This community is at-risk of transitioning to the invaded state. The state overall is stable and protected from excessive erosion. The biotic integrity of this plant community is fractured, due to the increasing presence of non-native species. Forage value will decrease or the wildlife value will shift toward different species. Depending on the non-native species of threat in this community, will determine the departure from normal function on all levels. The watershed is functioning, but with the increase in woody species (conifers/junipers), the risk of fire could decrease the stability and watershed function of the site.

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

-

mountain brome (Bromus marginatus), grass

-

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), grass

Figure 18. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 21. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forb | 350 | 750 | 1000 |

| Shrub/Vine | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 350 | 500 | 800 |

| Tree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1200 | 2000 | 2800 |

Table 22. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover | 0-5% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover | 10-30% |

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover | 40-60% |

| Forb foliar cover | 5-20% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 5-20% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-20% |

Table 23. Soil surface cover

| Tree basal cover | 0% |

|---|---|

| Shrub/vine/liana basal cover | 0% |

| Grass/grasslike basal cover | 0% |

| Forb basal cover | 0% |

| Non-vascular plants | 0% |

| Biological crusts | 0-5% |

| Litter | 5-20% |

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" | 0-15% |

| Surface fragments >3" | 0-15% |

| Bedrock | 0% |

| Water | 0% |

| Bare ground | 5-20% |

Table 24. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (ft) | Tree | Shrub/Vine | Grass/ Grasslike |

Forb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | – | 0-5% | 0-5% | 0-5% |

| >0.5 <= 1 | – | 5-15% | 10-30% | 10-20% |

| >1 <= 2 | – | 10-25% | 5-20% | 0-2% |

| >2 <= 4.5 | – | 0-5% | 0-10% | 0-2% |

| >4.5 <= 13 | – | – | – | – |

| >13 <= 40 | 0-5% | – | – | – |

| >40 <= 80 | – | – | – | – |

| >80 <= 120 | – | – | – | – |

| >120 | – | – | – | – |

Community 3.3

Invaded

The Native/Invasive community phase has maintained a representative sample of native perennial grasses and forbs that are key to this particular ecological site with the accompanying mountain big sagebrush component. Although this community phase is very vulnerable of becoming an invader driven system, if native grasses can maintain at least a 15% composition, there is still a chance that the community can be improved, extent of improvement and exuberant costs and labor required limit the economic feasibility. This community phase is characterized by a significant presence of invasive species composition (5% or greater) on the landscape, and are prominent on the site (referring to a wide scale composition, not one isolated patch in an isolated portion of the landscape). The litter or duff layer created by many of the known invasive species, but specifically cheatgrass, is significantly higher than the native community. This duff layer creates a barrier that can impede water infiltration and increase runoff, accelerating erosion. This is aggravated with increased slope. The duff layer creates an extreme hot zone during wildfires that can sterilize the soil through volatilization of needed nutrients or by the formation of an ash cap that seals the soils, preventing water infiltration and seed penetration, reducing the ability for re-vegetation post-disturbance. Production yields of the perennial grasses and forbs are reduced but the total production will maintain or may be slightly elevated due to the overall biomass and expanded growth potential of many of the annual or invasive species. A specific production range is not provided due to the variability of composition that will effect overall production.

Resilience management. Rangeland Health Implications/Indicators: This plant community is prone to further invasion with the added seed bank from the vigorous seed producer invaders. Plant diversity is moderate for this phase as the remnant perennials and the maintained composition of woody shrubs keeps a diverse community. The plant vigor is diminished and replacement capabilities are limited due to the reduced number of cool-season grasses. Plant litter is noticeably more when compared to reference communities due to the potential biomass produced by the invasive species (species dependent). Soil erosion is variable depending on the species of invasion and the litter accumulation thus associated. This variability also applies to water flow patterns and pedestalling. Infiltration is unaltered or slightly reduced; however as the duff layer or litter builds infiltration and runoff will increase.

Dominant plant species

-

mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana), shrub

-

Columbia needlegrass (Achnatherum nelsonii), grass

-

mountain brome (Bromus marginatus), grass

Pathway 3.1A

Community 3.1 to 3.2

The open canopy and reduced herbaceous composition that encouraged conifer encroachment allows for herbaceous species to also move or creep into the community. With added influences from the taller canopy and potential for snow catch and litter cover, non-native species such as Kentucky bluegrass, timonthy, orchardgrass, and brome grasses (smooth and pumpelly’s) will begin to encroach into the community. Drought, human or animal disturbance can exacerbate this transition. Introduction of seed into a disturbed or weakened community is the driving mechanism for the shift to a non-native community.

Context dependence. The community composition, or the specific species of concern, is dependent on the seed-source that is present. The species that is present is the determinant factor to the ability to restore the reference community.

Pathway 3.1B

Community 3.1 to 3.3

The encroachment of woody species is a result of disturbance or lack there of that provided open soil for establishment. This same foothold is a welcome opportunity for the aggressive invasive weed species to establish. Drought, human or animal disturbance can exacerbate this transition. Introduction of seed into a disturbed or weakened community is the driving mechanism for an invasion.

Context dependence. The extent of the invasion and the species of invasion is dependent on the seed source that was available or introduced and the mechanism of introduction. Wind, fire, animal movement, vehicle traffic, and other human activities all serve as a point source for weed movement. The expanse of the invasion, the duration it has existed, and the accessibility of the site are all factors affecting this community.

Pathway 3.2A

Community 3.2 to 3.3

The encroachment of non-native species provides the opportunity for more aggressive invasive species to take over a community. Drought, human or animal disturbance can exacerbate this transition. Introduction of seed into a disturbed ore weakened community is the driving mechanism for an invasion. Many areas of infestations can be linked to wildlife migration corridors, including birds. Another path of infestation is along roads, recreational areas, and trails. Seeds come in on vehicles, ORV's, pack animals, livestock, and domestic pets. A drought or disturbed community can remain relatively unaltered if no undesirable seed source is present. However, once seed is in the system, then the alteration of the community occurs quickly.

Context dependence. The species of invasion is the constraint to recovery. Many of the invasive weeds found on the high elevation at this time are treatable. The earlier a weed issue is detected and treated, the quicker the weed infestation can be curbed. But if not found or ignored, it can quickly become expensive and difficult to treat, if not impossible to eradicate.

State 4

Altered

Although the more temperate climate of this higher elevation counter-part to the basin and foothills site, the arid nature of this region has played a major role in the development and transitions in land use over time. Many landscapes were treated with a variety of prescriptions to manage sagebrush. Timber harvest recreation, and quarries/mining persist on this landscape, the larger use continues to be grazing. Initially, sheep were the most prominent, but currently cattle are more prominent with a few sheep allotments. Farming and general agricultural practices (hayland, headquarters) are not abundant at the higher elevations. However, development of small “cow camps”, recreational areas, trails, roads, and camp sites has played a major role in creating disturbances on the landscape.

Characteristics and indicators. These sites have been mined, harvested for timber, or had significant soil disturbance that has altered the site. Improved varieties, or species such as crested wheatgrass, Russian wildrye, or other species may be present on the landscape. Signs of seeding or soil manipulations is evident.

Resilience management. Once the soils have been disturbed with tillage, deep ripping, or significant soil loss or mixing, time is the function of resilience for any change of this site. If the process of restoration or reclamation of a community is applied, then the management to maintain this community will depend on the composition of the community planted and the disturbances that are involved on the specific location.

Community 4.1

Disturbed/Degraded Lands

Disturbed or degraded lands are characterized by alteration of the soils to a degree that the functionality (erosional, depositional, hydrological or chemical) and potential of the site has been impacted. Site specific evaluations need to be completed to determine the level of effect. The method and severity of alternation, as well as the spatial extent of the disturbance will determine vegetation response and management needs. Linear disturbances, such as trails and roads, will hold a different risk than patchwork or polygonal disturbances, such as timber sites or parking areas. Small scale or isolated disturbances (spot fires, burrowing sites) can be just as significant of a risk as a large scale disturbance (mined-lands). The growth curve of this plant community will vary depending on the successional species that are able to establish in an area. Early successional community growth curves may be similar to the native community. For a more accurate growth curve, a site specific species inventory and documentation of the climatic tendencies should be collected.

Resilience management. Rangeland Health Implications/Indicators: The plant community is variable and depending on the age of the stand and the stage of successional tendencies that the location is in will determine how stable (resilient/resistant) the community is. Plant diversity of these successional communities is generally strong, but is usually lacking in the structural groups that are desired on the site. In areas of new or frequent disturbance, annual weedy species or early successional plants will be the dominant cover, providing a strong diversity, but has minimal structural cover for some wildlife. As the community matures, or as the disturbance frequency is extended, perennial species (taller stature, stronger rooted) will increase providing protection and improving hydrology allowing other key species to establish. These stages within the community succession creates variability in composition and provides resiliency. Soil erosion is dependent on the disturbance regime and the resiliency of the community. The variability of the community also affects the water flow, infiltration, runoff, and pedestaling risk. Surface roughness (tire tracks, hoof action, smoothed, denuded surfaces, trails that may focus the water) is also influential to the resistance to erosion.

Community 4.2

Reclaimed Lands

Shifts in reclamation practices over the last several decades have altered the success and stability of reclaiming a site. Crested wheatgrass and smooth brome were species used frequently for reclamation throughout Wyoming; and across the state, many of these communities persist today. These stands are stable and generally persist as a monoculture until a disturbance creates a niche for native species to establish. Russian wildrye and varieties of rhizomatous and bunch-wheatgrasses are used in mixes to help increase establishment on many locations. Policies on federal lands, especially on forest lands, limits the use of non-native species and further limits where seed sources must be collected for use on these lands. Current interpretations of reclamation specifies the source of viable seed and the mix acceptable to achieve a composition as close to a natural (pre-disturbance) plant community as possible. This excludes the use of non-native species and allows for a more similar ecological response than what is expected with non- native species. These plantings will not replicate the reference community in response to management due to the change in soil dynamics with mechanical disturbance (seedbed preparation and seeding), but they may be similar. The growth curve of this plant community is generally species dependent, but the climatic limitations are the major driver of this system. The short growing season with persistant snow cover through early fall to late spring and delayed warm up are the limitations to seedling establishment. For non-typical seed mixes and for project specific scenarios, the species used and the climatic tendencies of the site must be considered, and appropriate adjustments made to the growth curve provided below.

Resilience management. Rangeland Health Implications/Indicators: Seeding mixtures will determine the plant community's resistance to change and resilience against the threat of invasive species and to erosion. Many of the stands established during seeding are diversity poor, but are better than monocultures that were seeded historically. Soil erosion is variable depending on the establishment of the seeding, how it is seeded, and mechanical procedures put in place. The variability of the water flow and pedestaling as well as infiltration and runoff is determined again by the species that comprise the community and the method of seeding (site preparation and seeding practice).

Pathway 4.1A

Community 4.1 to 4.2

Reclamation processes are necessary to shift a disturbed community back to a representative or functional plant community. Reclamation may include soil/dirt work to rebuild the soil profile (replace topsoil, land shaping, spoil placement), as well as re-seeding, integrated pest management, and long-term prescribed grazing or other managed use of the landscape. However, climatic variability and topography limits the success of seeding projects (accessibility by equipment, lack of suitable seed sources, limited growing season, and timing of precipitation). Proper preparation of a location to be seeded or once a site is seeded, integrated pest management becomes crucial to allow seedling establishment and to prevent undesirable species from invading the area. Brush management may be required to accommodate some areas to readily be seeded.

Context dependence. The existing plant community and the disturbance that led to the need for reclamation are factors influencing what preparations are necessary to begin the reclamation process and also determine the feasibility of restoring the desired community.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Critical Area Planting | |

| Fence | |

| Access Control | |

| Grazing Land Mechanical Treatment | |

| Heavy Use Area Protection | |

| Integrated Pest Management (IPM) | |

| Upland Wildlife Habitat Management | |

| Planned Grazing System | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Invasive Plant Species Control | |

| Grazing Management Plan | |

| Grazing management to improve wildlife habitat | |

| Intensive Management of Rotational Grazing | |

| Biological suppression and other non-chemical techniques to manage brush, weeds and invasive species | |

| Biological suppression and other non-chemical techniques to manage herbaceous weeds invasive species |

Pathway 4.2A

Community 4.2 to 4.1

If a reclaimed or restored site is not maintained or managed for the species implemented, the community will degrade over time. Non-use or lack of a disturbance regime to maintain function of the system can lead to a softening of the soils, loss of herbaceous cover, and increases erosion potential. In the same, over-use of the system by livestock or wildlife can also shift the composition or revert the site back to a degraded phase. The initial establishment phase of a reclaimed site is crucial to determine success, but at any stage of a seeding, degradation or further disturbance can occur forcing the site to phase back to the disturbed community.

Context dependence. Since the soils are altered from reference state due to seed-bed preparation, or mechanical disturbances associated with road/site development, timber harvest/mining, or other human activities, the plant community will not follow the same expected shifts as the native community. Monitoring and trend over time need to be recorded to determine if a location is degrading or adjusting with the climatic variables of the site.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Non-use or lack of fire will encourage mountain big sagebrush growth. Increases in crown density inhibiting grass growth begins the transition to a more shrub dominated state. Heavy, continuous season-long grazing, drought, and no fire will shift this community to the sagebrush/mixed grasses community within state 2. Timing of drought will have different effects on different plant species. Drier, more open winters has a greater detrimental impact to sagebrush and other shrubs in the community; while drier and warmer summers has impacts on the grasses and forbs within the community.

Constraints to recovery. Recovery is driven by the need to remove or thin the sagebrush stand. Restrictions on herbicide use, risk of control burns, and the ability to prevent infestation by non-native or invasive species during re-establishment of the desired key species are the constraints on this community's recovery.

Context dependence. Aspect or snow drifting will alter the species that tend to re-establish in the community following any disturbance or change. Wetter, more northerly aspect sites tend to favor sedges and forbs, where the drier more exposed sites tend to favor grasses.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Natural disturbances and/or human driven impacts with the presence of a seed source will encourage the establishment of noxious weeds within this community. Disturbances that disrupt the native canopy exposing soil is the key factor in weed establishment. Heavy use areas by recreationalists, livestock or wildlife, stock drives, roads and trails are major areas for initial establishment. Movement of timber harvest equipment through an area is another point source for weed establishment.

Constraints to recovery. The inability to eradicate non-native and invasive species is the restrictive factor preventing recovery of this community.

Context dependence. The level of severity of the disturbance, the type of disturbance (soil disturbance or disturbances to the vegetation), and the seed sources present determine the specific components of the encroached or invaded plant communities. The level of ground disturbance will determine the risk of invasion and the time required for the community to shift to this degraded state. The ripping that occurs with timber harvest access will require a different successional transition of the plant community than areas that are torn by vehicle traffic on wet soils. The specific species introduction through wildlife movement, livestock, and human activities determine the community composition. Animal fur, tires/vehicles, clothing, and wind/water are all sources that introduce undesirable species into areas. The introduction of species is generally unintentional, and the delivery mechanism is unaware of their contributions.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Grazing management with deferred, rotational, or targeted grazing will encourage grass production, and can assist with reduction in woody species and forbs. Brush management with prescribed fire or herbaceous chemical control may be needed if woody canopy is over 30% cover and the forbs are suppressing the grasses in the community (State 2.2) to return to State 1 – Reference. Applying the intensity of animal impact to reduce the sagebrush cover may hinder or prevent the recovery of key grass species in the community. Risk assessment to determine the most beneficial means of reducing the woody overstory and to improve the native herbaceous understory will need to be completed for each specific community.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning | |

| Critical Area Planting | |

| Fence | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Grazing Land Mechanical Treatment | |

| Heavy Use Area Protection | |

| Integrated Pest Management (IPM) | |

| Upland Wildlife Habitat Management | |

| Prescribed Grazing | |

| Invasive Plant Species Control | |

| Grazing Management Plan | |

| Grazing management to improve wildlife habitat | |

| Intensive Management of Rotational Grazing | |

| Biological suppression and other non-chemical techniques to manage brush, weeds and invasive species | |

| Biological suppression and other non-chemical techniques to manage herbaceous weeds invasive species | |

| Herbaceous Weed Control | |

| Prescriptive grazing management system for grazed lands |

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

Once a site has transitioned to this state, the increased bare ground and weakened plant structure leaves the community for encroachment or species creep by non-native species such as Kentucky bluegrass, dandelions, smooth brome, and in some instances, conifers. Thistles, toadflax, and houndstounge are quickly becoming significant problems on areas within these weakened plant communities. Increasing bare ground and weakening plant community structure leaves the community vulnerable to invader species such as toadflax and houndstongue.

Constraints to recovery. The inability to effectively eradicate the undesirable species is the known financially limiting constraint to this site recovering.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 3

Following a ground disturbance, whether planned or incidental in nature, provides a niche for non-native species to establish. This same niche is an opportunity for non-typical natives (juniper/spruce) to encroach into the area. Disturbance by means of equipment, vehicles, or human activity, as well as domestic animals and wildlife provide a means for introducing seed sources for these undesirable species into the system. Planned disturbances, seeding or development activities provides the open niche for invasive species to establish in an area. Ground disturbances of any nature introduces seed sources from surrounding areas into a prime seedbed. In the reclamation or restoration process, if no management is put into place to prevent an infestation of weeds, the community will transition (or possibly revert back) to an invaded state. Wildfire, prescribed burning, drought, or frequent and severe over-use by large herbivores can be a source of the disturbance that either opens the canopy and/or introduces the species to the location. Extended periods of non-use creates a decadent community with a large proportion of dead growth persisting around the crown of the plants, reducing vigor and production. As the plants begin to die-back, the community becomes vulnerable to weed invasions. This invasion triggers the transition to an invaded state.

Constraints to recovery. The inability to eradicate most of the non-native and invasive species is the major factor preventing recovery of this site. Recovery, in this instance, would require reseeding with further ground disturbance. Cost of implementation and risks involved limit the feasibility of reclaiming or restoring a native community.

Additional community tables

Table 25. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Tall-stature, Cool-Season Bunchgrasses | 625–1250 | ||||

| Columbia needlegrass | ACNE9 | Achnatherum nelsonii | 375–625 | 15–25 | ||

| slender wheatgrass | ELTR7 | Elymus trachycaulus | 250–500 | 10–20 | ||

| mountain brome | BRMA4 | Bromus marginatus | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| 2 | Mid-stature, Cool-season Bunchgrasses | 375–750 | ||||

| Idaho fescue | FEID | Festuca idahoensis | 375–625 | 15–25 | ||

| Letterman's needlegrass | ACLE9 | Achnatherum lettermanii | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| 3 | Rhizomatous Grasses | 250–500 | ||||

| Montana wheatgrass | ELAL7 | Elymus albicans | 250–375 | 0–5 | ||

| oniongrass | MEBU | Melica bulbosa | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| spike fescue | LEKI2 | Leucopoa kingii | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| 4 | Short-stature, Cool-season Grasses | 250–500 | ||||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| Cusick's bluegrass | POCU3 | Poa cusickii | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| muttongrass | POFE | Poa fendleriana | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| onespike danthonia | DAUN | Danthonia unispicata | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| timber oatgrass | DAIN | Danthonia intermedia | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| spike trisetum | TRSP2 | Trisetum spicatum | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| prairie Junegrass | KOMA | Koeleria macrantha | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| 5 | Miscellaneous Grasses and Grass-likes | 0–50 | ||||

| needleleaf sedge | CADU6 | Carex duriuscula | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| Geyer's sedge | CAGE2 | Carex geyeri | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| Grass, perennial | 2GP | Grass, perennial | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 6 | Perennial Forbs | 250–500 | ||||

| American vetch | VIAM | Vicia americana | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| aster | ASTER | Aster | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| avens | GEUM | Geum | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| balsamroot | BALSA | Balsamorhiza | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| desertparsley | LOMAT | Lomatium | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| bluebells | MERTE | Mertensia | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| fleabane | ERIGE2 | Erigeron | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| buttercup | RANUN | Ranunculus | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| American bistort | POBI6 | Polygonum bistortoides | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| flax | LINUM | Linum | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| geranium | GERAN | Geranium | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| elkweed | FRSP | Frasera speciosa | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| hawksbeard | CREPI | Crepis | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| giant hyssop | AGAST | Agastache | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| little larkspur | DEBI | Delphinium bicolor | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| locoweed | OXYTR | Oxytropis | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| lupine | LUPIN | Lupinus | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| sego lily | CANU3 | Calochortus nuttallii | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| milkvetch | ASTRA | Astragalus | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| pale agoseris | AGGL | Agoseris glauca | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| mountain deathcamas | ZIEL2 | Zigadenus elegans | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| mule-ears | WYAM | Wyethia amplexicaulis | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||

| onion | ALLIU | Allium | 0–125 | 0–5 | ||